Abstract

Echinacea preparations are widely used herbal medicines for the prevention and treatment of colds and minor infections. There is little evidence for the individual components in Echinacea that contribute to immune regulatory activity. Activity of an ethanolic Echinacea extract and several constituents, including cichoric acid, have been examined using three in vitro measures of macrophage immune function – NF-κB, TNF- α and nitric oxide (NO). In cultured macrophages, all components except the monoene alkylamide (AA1) decreased lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated NF-κB levels. 0.2 µg/ml cichoric acid and 2.0µg/mL Echinacea Premium Liquid (EPL) and EPL alkylamide fraction (EPL AA) were found to significantly decrease TNF-α production under LPS stimulated conditions in macrophages. In macrophages, only the alkylamide mixture isolated from the ethanolic Echinacea extract decreased LPS stimulated NO production. In this study, the mixture of alkylamides in the Echinacea ethanolic liquid extract did not respond in the same manner in the assays as the individual alkylamides investigated. While cichoric acid has been shown to affect NF-κB, TNF-α and NO levels, it is unlikely to be relevant in the Echinacea alterations of the immune response in vivo due to its non- bioavailability – i.e. no demonstrated absorption across the intestinal barrier and no detectable levels in plasma. These results demonstrate that Echinacea is an effective modulator of macrophage immune responses in vitro.

Introduction

Echinacea has been used for many years for the prevention and treatment of colds and minor infections. There is some evidence to indicate that Echinacea preparations might work through immune mechanisms [1,2], however, the immune response is complex and multifaceted, with macrophages playing a key role in the orchestration of the response. Macrophages are widely distributed in different tissues and play an essential role in the development of the specific and non- specific immune response. These cells are activated by a variety of stimuli such as bacterial components, cytokines and chemicals. Once activated, macrophages produce and release numerous secretory products which have biological activity [3]. These include several cytokines such as TNF-α, and reactive nitrogen intermediates. Activated macrophages generally produce large quantities of nitric oxide (NO) which is biologically active at nanomolar concentrations, playing an important physiological role as a defence molecule in the immune system [4]. NO is synthesised by nitric oxide synthases (NOS) of which three isoforms have been identified. One of these isoforms, iNOS, is not constitutively expressed but it can be rapidly induced by inflammatory stimuli including lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and cytokines. [5]. LPS is known to induce iNOS gene expression via a nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) mediated pathway [6,7]. The cytokine, TNF-α also activates NF-κB and induction leads to the transcription of a host of proinflammatory cytokines and other molecules which play a key role in the inflammatory process. In this study we looked at the effects of ethanolic extracts of Echinacea, the most usual oral dosing form, on NF-κB, TNF-α and NO. These extracts contain two major groups of compounds – caffeic acid conjugates and alkylamides. Standardisation of many Echinacea extracts to cichoric acid implies that it is responsible for therapeutic activity and not the alkylamides which are also present. A recent in vitro study [8] has shown that cichoric acid and caffeic acid conjugates in general have poor bioavailability and therefore are unlikely to contribute to the immune activity of an oral Echinacea product. We have investigated the activity of an ethanolic Echinacea extract containing both caffeic acid conjugates and alkylamides and compared it to that of the alkylamide fraction alone, cichoric acid and two synthetic isolated alkylamides in an attempt to separate their contributions in vitro and as such to predict their actions in vivo after an oral dose.

Results and Discussion

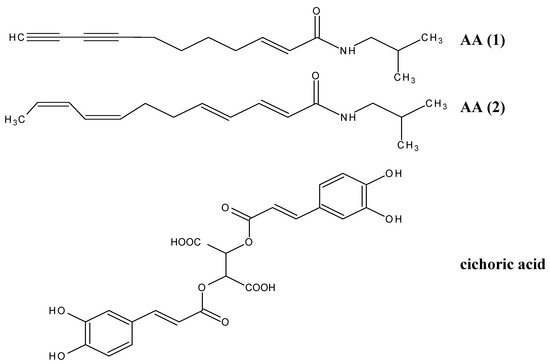

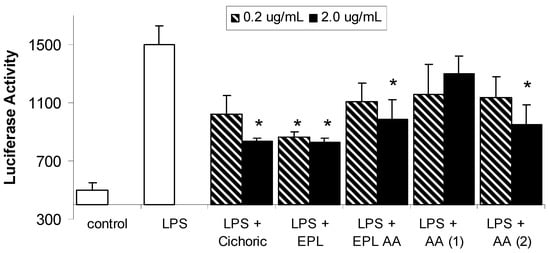

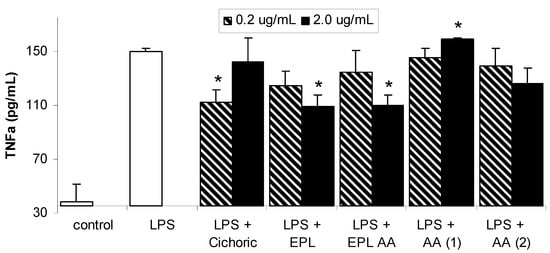

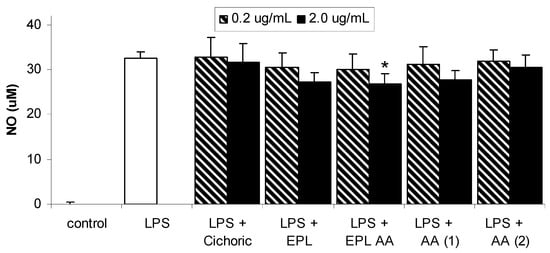

The structures of the individual Echinacea components investigated in this study are given in Figure 1. Each of these components is present in the ethanolic echinacea extract (Echinacea Premium Liquid – EPL) together with many other alkylamide and caffeic acid derivatives. The EPL alkylamide (EPL AA) fraction does not contain the caffeic acid derivatives, only the alkylamides of which alkylamide 1 (AA 1) is the major 2-ene alkylamide and alkylamide 2 (AA 2) is the major 2,4-diene alkylamide. The effect of LPS in the presence and absence of the Echinacea components on NF-κB is shown in Figure 2. LPS significantly increased NF-κB concentrations from basal levels, with expression increasing from 501 ± 46 to 1500 ± 127 units. Although all Echinacea fractions lowered LPS-induced NF-κB, only 2.0 µg/mL cichoric acid, both concentrations of EPL, 2.0 µg/mL EPL AA and 2.0 µg/mL AA 2 significantly decreased NF-κB concentrations. Figure 3 shows the effect of Echinacea and its components on the LPS-stimulated changes in TNF-α concentrations. LPS increased TNF-α levels from basal levels however this increase was inhibited in the presence of 0.2 µg/mL cichoric acid, 2.0 µg/mL EPL and 2.0 µg/mL EPL AA. In contrast to this inhibition, 2.0 µg/mL AA 1 significantly increased TNF-α levels over compared with those found with LPS alone. Although LPS markedly stimulated nitric oxide (NO) production (Figure 4) only 2.0 µg/mL EPL AA was able to cause minor but significant inhibition.

Figure 1.

Structures of alkylamides and cichoric acid. (AA 1) (2E)-N-isobutylundeca- 2-ene-8,10-diynamide; (AA 2) (2E,4E,8Z,10Z)-N-isobutyldodeca-2,4,8,10- tetraenamide; cichoric acid.

Figure 2.

Effects of chinacea and its components on LPS-induced NF-kB expression levels in macrophages. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 3; * significantly different from LPS only stimulated cells where p< 0.05.

Figure 3.

Effects of Echinacea and its components on LPS-induced TNF-α expression in macrophages. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 3. * significantly different from LPS only stimulated cells, where p< 0.05.

Figure 4.

Effects of Echinacea and its components on LPS-induced nitric oxide production in macrophages. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM for n = 6. * significantly different from LPS only stimulated cells, where p< 0.05.

Macrophages undergo a process of cellular “activation” which is associated with morphological, functional, and biochemical changes in the cells in response to inflammatory signals or antigens. One prominent characteristic of activated macrophages is their increased capacity to release pro- inflammatory and cytotoxic mediators, which help aid in the resolution of infection or inflammation. As a prelude to macrophage activation LPS must bind to a receptor on the macrophage cell surface. Several LPS receptors have been identified in different macrophages with the most thoroughly studied receptor being the CD14 receptor. The mouse peritoneal macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7 used in this study possesses the CD14 receptor [9].

Conclusions

The present data show that all components tested except the monoene alkylamide (AA 1) significantly decreased lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated NF-κB levels. Only cichoric, EPL and the alkylamide mixture (EPL AA) significantly decreased TNF-α production under LPS stimulated conditions in macrophages. Only the EPL AA decreased LPS stimulated NO production. Studies on the immunomodulatory activity of alkylamides are limited but interestingly, Goel et al., [10] have shown that the alkylamide fraction of an Echinacea plant extract produced significantly more TNF-α and NO from rat alveolar macrophages stimulated ex vivo with LPS. In this study, the mixture of alkylamides in the Echinacea ethanolic liquid extract did not respond in the same manner in the assays as the individual alkylamides investigated. While cichoric acid has been shown to affect NF-κB, TNF- α and NO levels [1,12], it is unlikely to be relevant in the Echinacea alterations of the immune response in vivo due to its non-bioavailability – i.e. no demonstrated absorption across the intestinal barrier and no detectable levels in plasma [8]. These results demonstrate that Echinacea is an effective modulator of macrophage immune responses in vitro and that further clinical study would be merited to investigate the immunomodulatory properties of alkylamides.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by AUSINDUSTRY through a Biotechnology Innovation Fund Grant (No BIF02651) and MediHerb Pty Ltd. The pNFκB-Luc and pSV-β-galactosidase vectors were kindly provided by Dr Alaina Ammit, University of Sydney.

Experimental

Sample preparation

Alkylamides AA 1 and AA 2 (Figure 1) were synthesised according to the method described by Matthias et al [8]. An ethanolic extract (Echinacea Premium Liquid; EPL), of Echinacea purpurea (300 mg/mL) and Echinacea angustifolia roots (200 mg/mL) was obtained from MediHerb Pty Ltd, Warwick, Australia. The EPL alkylamide fraction (EPL AA) was separated from the caffeic acid fraction by diluting 1:100 with water and loading onto a SPE cartridge (Strata C18-E; 55 mm, 70 Å; 500 mg/6 mL; Phenomonex, USA) conditioned with 70% ethanol (10 mL), then water (5 mL). The caffeic acids were eluted from the column with water and 7% ethanol and then discarded. The alkylamide fraction was eluted with 70% ethanol and diluted back to a concentration equivalent to that found initially in the ethanolic extract. Cichoric acid was purchased from ChromaDex, CA, USA.

Cell Culture

All reagents, unless otherwise stated, were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264 from the European Collection of Cell Cultures was routinely cultured in 75 cm2 flasks DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cell culture media and supplements and Lipofectamine reagent were obtained from Gibco/ Invitrogen, CA USA.

NF-κB activity assay

For the assay, RAW 264 mouse macrophage cells (passage no. 8) were plated out at 5 x 105 cells/mL, 500 μL/well in 24-well cell culture plates (Nunc) containing the same media as described above but without antibiotics. The cells were allowed to grow overnight at 37°C and 5% CO2. Transfection of the cells with pNFκB-Luc and pSV-β-galactosidase control vector was carried out according to Aktan et al. [12]. Cells were incubated for 48 h before addition of samples. The cells were preincubated for 1 hour with the test compounds or vehicle before addition of 0.1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and incubation for a further 3 hours. Unstimulated cells were used as the negative control. Following this, the media was aspirated, wells washed twice with PBS, and Glo Lysis buffer (100 μL/well) was added. After incubation (room temperature for 5 min) cell lysates were assayed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities according to the Promega protocols. Results were expressed as luciferase activity (luciferase luminescence counts per sec normalised with β- galactosidase absorbance).

TNF-α assay

For the assay, RAW 264 mouse macrophage cells (passage no. 6) were plated out in 96 well plates at 106 cells/mL, 100 μL/well in the same media as described above but without phenol red, and were allowed to attach overnight. The cells were preincubated for 1 hour with the test compounds or vehicle before addition of 0.1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and incubation for a further 20 hours. Cell supernatants were collected and assayed for TNFα using the Cytimmune Mouse TNFα kit (AMS Biotechnology, Abingdon, Oxon, UK), according to the kit protocol. Results were expressed as pg/mL TNF-α.

Nitrite assay

The same supernatants obtained for the TNF-α assay were also assayed for NO, using the Griess reaction. Equal volumes of supernatant and Griess reagent (0.1% N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamide dihydrochloride, 1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid) were mixed and absorbances at 550 nm were compared to a sodium nitrite standard curve. Results were expressed as μM nitrite.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical difference between the groups was determined by Student t test.

References

- Goel, V.; Chang, C.; Slama, J.; Barton, R.; Bauer, R.; Gahler, R.; Basu, T.K. Echinacea stimulates macrophage function in the lung and spleen of normal rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, R.K.; Gellenbeck, K.; Stonebrook, K.; Brovelli, E.; Qian, Y.; Bankaitis-Davis, D.; Cheronis, J. Regulation of human immune gene expression as influenced by a commercial blended Echinacea product: preliminary studies. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003, 228, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, H.J.; Torres, M. Redox signalling in macrophages. Mol. Aspects Med. 2001, 22, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, A.J.; Higgs, A.; Moncada, S. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase as a potential therapeutic agent. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999, 39, 191–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Marsden, P.A. Nitric oxide synthases: gene structure and regulation. Adv. Pharmacol. 1995, 34, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.W.; Kashiwabara, Y.; Nathan, C. Role of NF<B/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 4705–4708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Forstermann, U.; Kleinert, H. Nitric oxide synthase: expression and expressional control of the three isoforms. Naunyn Schmidebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1995, 352, 351–364. [Google Scholar]

- Matthias, A.; Blanchfield, J.T.; Penman, K.G.; Toth, I.; Lang, C-S.; De Voss, J.J.; Lehmann, R.P. Permeability studies of alkylamides and caffeic acid conjugates from echinacea using a Caco-2 cell monolayer model. J. Clin. Pharm. Therap 2004, 29, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchens, R.L.; Munford, R.S. Enzymatically deacylated lipopolysaccharide (LPS) can antagonize LPS at multiple sites in the LPS recognition pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 9904–9910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goel, V.; Chang, C.; Slama, J.; Barton, R.; Bauer, R.; Gahler, R.; Basu, T.K. Alkylamides of Echinacea purpurea stimulate alveolar macrophage function in normal rats. Int. J. Immuno- pharmacol. 2002, 2, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertsch, J.; Schoop, R.; Kuenzle, U.; Suter, A. Echinacea alkylamides modulate TNF-α gene expression via cannaboid receptor CB2 and multiple signal transduction pathways. FEBS Letters 2004, 577, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktan, F.; Henness, S; Roufogalis, B.D.; Ammit, A.J. Gypenosides derived from Gynostemma pentaphyllum suppress NO synthesis in murine macrophages by inhibiting iNOS enzymatic activity and attenuating NF- κB-mediated iNOS protein expression. Nitric Oxide 2003, 8, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Not available

© 2005 by MDPI (http:www.mdpi.org). Reproduction is permitted for noncommercial purposes.