Conceptual Model of Emergency Department Utilization among Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Patients: A Critical Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Models and Critical Reviews

2.2. Definining Primary Endpoints

2.2.1. ED Utilization

2.2.2. ED Length of Stay (LOS)

2.2.3. ED Revisit

2.3. Conceptual Basis

2.3.1. Social-Ecological Model (SEM)

2.3.2. Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use and the PRECEDE-PROCEDE Model

2.4. Literature Search

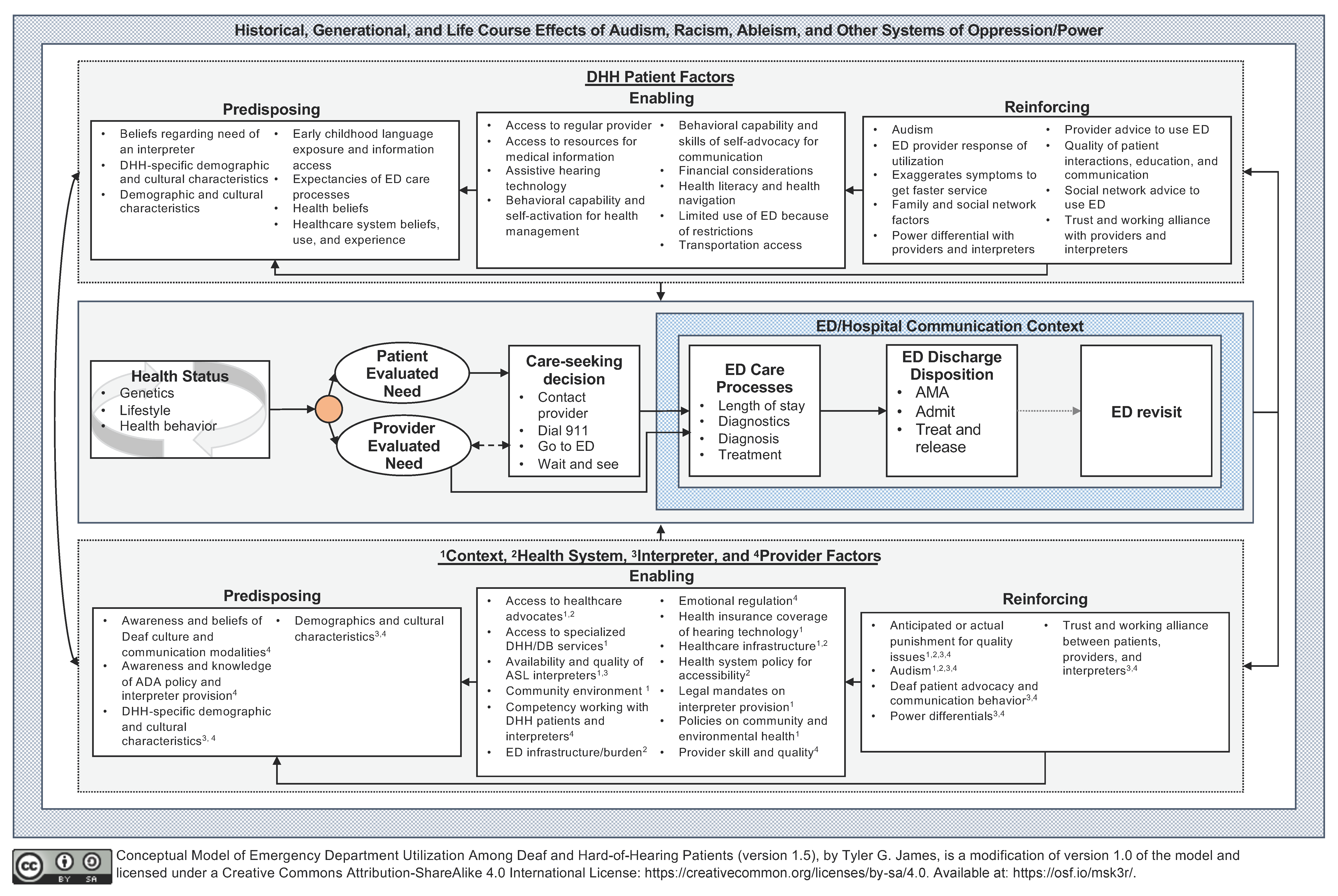

3. Proposed Conceptual Model and Literature Support

3.1. Health Status: Genetics, Lifestyle, and Health Behavior

3.2. Need and the Care-Seeking Decision

3.3. ED Care Processes, Discharge, and Revisit

3.4. ED Communication Context

4. Applying the Model for Hypothesis Generation, Research, and Practice

- Patient predisposing: The development of health beliefs and social norms for DHH patients, specifically group dynamics among DHH ASL-users and non-DHH people.

- Patient reinforcing: Mediating and moderating factors of how provider education to DHH patients influence knowledge and skills development.

- Non-patient enabling: The impact of health policy (e.g., Medicaid expansion) on reducing DHH patient health inequities.

- Non-patient enabling and reinforcing: How DHH patient advocacy for effective communication impacts ED providers’ perception of the patient.

- Health service outcomes: Cost-effectiveness studies to identify the impact of preventing chronic health conditions among DHH people to justify resource allocation to health promotion programs.

- ED outcomes: How interpreter provision accelerates or delays ED length of stay for DHH ASL-using patients.

- ED outcomes: How the communication context influences patient safety events and diagnostic delays among DHH patients.

4.1. Assumptions

4.2. Limitatiions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Definition | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposing: Beliefs regarding need of an interpreter a,b,d | DHH ASL-users may assess their need for an interpreter during a medical encounter based on the complexity of the situation and the expected amount of communication needed. This construct may align strongly with perceived threat (as described in the Health Belief Model) of not having an interpreter. | [65,94] |

| Predisposing: DHH-specific demographic and cultural characteristics a,b,d | Characteristics that are unique to DHH individuals, such as:

| [15,26,90,94,105,114,115] |

| Predisposing: Demographic and cultural characteristics a,c,d | General demographic characteristics, including:

| [15,26,38,94,100,101,105,116,117] |

| Predisposing: Early childhood language exposure and information access b,d | Describes the DHH patient’s early childhood language environment, including experience of language deprivation, and access to incidental learning and indirect communication. | [58,60,63,64,65,115,118,119,120] |

| Predisposing: Expectancies of ED care processes a,c | Describes patient expectations of using the ED including:

| [38,94,98,99,100,101] |

| Predisposing: Healthcare system beliefs, use, and experience b,d | General healthcare beliefs, utilization, experiences and satisfaction including:

| [24,38,98,99] |

| Predisposing: Health beliefs b,d | Beliefs and cognitive appraisals related to health behavior such as:

| [38,41,98,99,121] |

| Enabling: Access to a regular provider a,b | Access to a usual provider that can provide an alternative source of care for patients seeking ED services, or provide health-promoting information. | [65,90,94] |

| Enabling: Access to resources for medical information b | Provision of/access to health education/promotion materials (e.g., captioned videos with ASL) that educate patients on chronic condition management, risks, treatment options, and prevention. | [65,114] |

| Enabling: Assistive hearing technology b,d | A patient’s use of assistive hearing technology (e.g., hearing aids) and if/how it augments their communication access. | [9,77] |

| Enabling: Behavioral capability and self-activation for health management b,d | Patient’s understanding and skill set to do a behavior, including being involved in their healthcare decisions. This construct describes factors such as:

| [41,65,77] |

| Enabling: Behavioral capability and skills of self-advocacy for communication a,b | Describes a DHH patient’s skills for advocating for communication access, including:

| [65,94,97,114] |

| Enabling: Financial considerations a,b,c | Financial considerations describe a patient’s cognitive processes and available resources regarding:

| [15,16,23,45,98,100,101,114] |

| Enabling: Health literacy and health navigation a,b,c,d | Abilities related to the overall construct of health literacy and health navigation including:

| [15,24,64,65,93,98,99,101,114,122] |

| Enabling: Limited use of ED because of restrictions c | Idiosyncratic restrictions that prevent ED utilization, such as caregiving responsibilities to a family member or pet. | [98,99] |

| Enabling: Transportation access c | A patient’s access to transportation with consideration of their distance to care. Transportation access is influenced by access to social and economic resources. | [38,98,101,102,122] |

| Reinforcing: Audism b,d | Individual “beliefs and behaviors that assume the superiority of being hearing over being Deaf” [56], an institutional “system of advantage based on hearing ability” [56], and “a metaphysical orientation that links human identity with speech” (Bauman, 2004, p. 245). Examples of audism include:

| [56,59,123] |

| Reinforcing: ED provider response of utilization c | An ED provider may respond in different ways to a patient’s use of the ED, particularly when it is deemed medically non-urgent. This response may include:

| [124] |

| Reinforcing: Exaggeration of symptoms b | Healthcare encounters when patients exaggerate or fake symptoms, such as complaining about chest pains when there are none, to change the process of care (e.g., getting faster care). | [65] |

| Reinforcing: Family and social network factors a,b,d | Family members’, friends’, and others in the patient’s social network influence on health behavior and healthcare-seeking including:

| [38,41,64,65,94,115] |

| Reinforcing: Power differential with patients, providers, and interpreters a,b,d | Describes the power differential between patients and their healthcare providers and/or ASL interpreters.

| [65,94,95,123] |

| Reinforcing: Provider advice to use ED a,c | Communication received from usual care providers for patients to initially use or revisit an ED during specific situations (e.g., time of day, experiencing specific symptoms). | [38,94,98] |

| Reinforcing: Quality of patient interactions, education, and communication a,b,c | Concepts regarding the quality of the provision of patient education and patient satisfaction with their patient-provider relationship, such as:

| [22,24,94,114,116,125,126] |

| Reinforcing: Social network advice to use ED a,c,d | Recommendations to seek care at (or revisit) an ED from individuals within the patient’s social network including friends or family members, particularly those who have experience with the condition or healthcare system. These recommendations may be unsolicited or solicited. | [38,45,94,98] |

| Reinforcing: Trust and working alliance with providers and interpreters a,c,d | Describes trust between patients, providers, and interpreters including:

| [38,65,94,98,101,114] |

| Construct | Definition | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposing: Awareness and beliefs of Deaf culture and communication modalities a,c,d | Describes a healthcare provider’s awareness of Deaf culture and accessible communication modalities including:

| [15,65,94,95,97,108,126] |

| Predisposing: Awareness of ADA policy and interpreter provision a,b | Describes a healthcare provider’s awareness of their healthcare system’s accommodations policy and who is responsible for providing accommodations. Domains include:

| [15,94,95,105,108,126] |

| Predisposing: DHH-specific demographic and cultural characteristics b,d | Describes characteristics of interpreters or medical providers who may be DHH including:

| [127,128,129] |

| Predisposing: Demographics and cultural characteristics c,d | General demographic characteristics of interpreters and medical providers, including:

| [130,131] |

| Enabling: Access to healthcare advocates a,b,d | Access to advocates for navigation or communication access that remove barriers and stressors for the patient. Relevant characteristics include:

| [94,114] |

| Enabling: Access to specialized DHH/DB services b,d | Access to specialized DHH and DeafBlind services which can provide:

| [26,94,114] |

| Enabling: Availability and quality of ASL interpreters a,b | Describes the availability of ASL/English interpreters and the quality of those interpreters including:

| [15,22,24,65,94,97,126,132,133] |

| Enabling: Community environment c,d | Community physical and social environment factors including:

| [42,46,101] |

| Enabling: Competency working with DHH patients and interpreters a,b,d | Describes a provider’s skillset working with DHH patients and interpreters including:

| [65,94,95,96,97] |

| Enabling: ED infrastructure and burden a,b,c | ED system factors including:Consulting physician attitudes and availability ED census and over-crowdingUnderstaffing and turnover of ED staff and providers | [65,94,103,104] |

| Enabling: Emotional regulation c | An ED provider’s strategies to regulate their emotions which impact their provision of patient-centered care, including:

| [103] |

| Enabling: Health insurance coverage of hearing technology b,d | The cost of accessible hearing technology (e.g., hearing aids) – commonly not covered by insurance – is prohibitive to their usage. | [9,114] |

| Enabling: Healthcare infrastructure b,c,d | Describes the local healthcare infrastructure including:

| [38,103,134] |

| Enabling: Health system policy for accessibility a,b | Hospital/health system characteristics and accessibility polices that influence provider and patient communication by:

| [94,105,116,126] |

| Enabling: Legal mandates on interpreter provision b,d | Federal, state, and local policies regarding interpreter provision and the quality of interpreter services. | [65,135,136] |

| Enabling: Policies on community and environmental health c,d | Federal, state, and local policies (e.g., public health law) that impact community and environmental health. | [41,101] |

| Enabling: Provider skill and quality b,d | Describes a medical provider’s overall skillset and quality including:

| [114] |

| Reinforcing: Anticipated or actual punishment for quality issues a,b,d | Salience of provider and interpreter professional malpractice, and/or accessibility violation dispute mechanisms on provider, interpreter, and health system behavior, including:

| [105,116,126] |

| Reinforcing: Audism b,d | Individual “beliefs and behaviors that assume the superiority of being hearing over being Deaf” [56], an institutional “system of advantage based on hearing ability” [56], and “a metaphysical orientation that links human identity with speech” (Bauman, 2004, p. 245). Examples of audism include:

| [56,59,123] |

| Reinforcing: DHH patient’s advocacy and communication behavior a,b,c | A DHH patient’s behavior during healthcare encounters and its related outcomes including:

| [65,94,103,104,132] |

| Reinforcing: Power differential between patients, providers, and interpreters a,b,d | Describes the power differential between patients and their healthcare providers and/or ASL interpreters.

| [65,94,127] |

| Reinforcing: Trust and working alliance between patients, providers, and interpreters a,b,c | Describes trust between patients, providers, and interpreters including:

| [38,65,94,98,101,114,127] |

References

- Moore, B.J.; Stocks, C.; Owens, P.L. Trends in Emergency Department Visits, 2006–2014; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2012: With Special Feature on Emergency Care; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2013.

- Coster, J.E.; Turner, J.K.; Bradbury, D.; Cantrell, A. Why Do People Choose Emergency and Urgent Care Services? A Rapid Review Utilizing a Systematic Literature Search and Narrative Synthesis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2017, 24, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.A.; Baicker, K.; Taubman, S.; Finkelstein, A.N. The Uninsured Do Not Use the Emergency Department More-They Use Other Care Less. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 2115–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.E.; Burton, R.; Hixon, B.; Kakade, M.; Bhagalia, P.; Vick, C.; Edwards, A.; Hawn, M.T. Factors Influencing Emergency Department Preference for Access to Healthcare. West J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 13, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capp, R.; Kelley, L.; Ellis, P.; Carmona, J.; Lofton, A.; Cobbs-Lomax, D.; D’onofrio, G. Reasons for Frequent Emergency Department Use by Medicaid Enrollees: A Qualitative Study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Machlin, S.; Chowdhury, S. Expenses and Characteristics of Physician Visits in Different Ambulatory Care Settings, 2008; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2011.

- Sommers, A.S.; Boukus, E.R.; Carrier, E. Dispelling Myths about Emergency Department Use: Majority of Medicaid Vists Are for Urgent or More Serious Symptoms; Center for Studying Health System Change: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, M.M.; Lin, F.R.; Zazove, P. State of Research and Program Development for Adults with Hearing Loss. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030 Objectives. Available online: https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/browse-objectives (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020 Framework. Available online: https://www.healthypeople.gov/sites/default/files/HP2020Framework.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2020).

- Agrawal, Y.; Platz, E.A.; Niparko, J.K. Prevalence of Hearing Loss and Differences by Demographic Characteristics among US Adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 1522–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnett, S.; Franks, P. Health Care Utilization and Adults Who Are Deaf: Relationship with Age at Onset of Deafness. Health Serv. Res. 2002, 37, 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Padden, C.A.; Humphries, T. Deaf in America: Voices from a Culture; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, M.M.; Winters, P.C.; Sen, A.; Zazove, P.; Fiscella, K. Emergency Department Utilization among Deaf American Sign Language Users. Disabil. Health J. 2015, 8, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reed, N.S.; Altan, A.; Deal, J.A.; Yeh, C.; Kravetz, A.D.; Wallhagen, M.; Lin, F.R. Trends in Health Care Costs and Utilization Associated with Untreated Hearing Loss over 10 Years. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019, 145, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earp, J.; Ennett, S. Conceptual Models for Health Education Research and Practice. Health Educ. Res. 1991, 6, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudreaux, E.D.; Cydulka, R.; Bock, B.; Borrelli, B.; Bernstein, S.L. Conceptual Models of Health Behavior: Research in the Emergency Care Settings. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009, 16, 1120–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paradies, Y.; Stevens, M. Conceptual Diagrams in Public Health Research. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 1012–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ravitch, S.M.; Riggan, J.M. Introduction to Conceptual Frameworks. In Reason & Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research; SAGE Publications Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, J.M.; Baker, E.F.; Iserson, K.V.; Kluesner, N.H.; Marshall, K.D.; Vearrier, L. Use of Interpreter Services in the Emergency Department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, 72, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anglemyer, E.; Crespi, C. Misinterpretation of Psychiatric Illness in Deaf Patients: Two Case Reports. Case Rep. Psychiatry 2018, 2018, 3285153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barnett, S.; Matthews, K.A.; Sutter, E.J.; DeWindt, L.A.; Pransky, J.A.; O’Hearn, A.M.; David, T.M.; Pollard, R.Q., Jr.; Samar, V.J.; Pearson, T.A. Collaboration with Deaf Communities to Conduct Accessible Health Surveillance. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, S250–S254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sheppard, K. Deaf Adults and Health Care: Giving Voice to Their Stories. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2013, 26, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, T.G.; McKee, M.M.; Sullivan, M.K.; Ashton, G.; Hardy, S.J.; Santiago, Y.; Phillips, D.G.; Cheong, J. Community-Engaged Needs Assessment of Deaf American Sign Language Users in Florida, 2018. Public Health Rep. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on the Future of Emergency Care in the US Health System. Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point; Institute of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Salway, R.; Valenzuela, R.; Shoenberger, J.; Mallon, W.; Viccellio, A. Emergency Department (ED) Overcrowding: Evidence-Based Answers to Frequently Asked Questions. Rev. Médica Clínica Condes 2017, 28, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiler, J.L.; Handel, D.A.; Ginde, A.A.; Aronsky, D.; Genes, N.G.; Hackman, J.L.; Hilton, J.A.; Hwang, U.; Kamali, M.; Pines, J.M.; et al. Predictors of Patient Length of Stay in 9 Emergency Departments. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2012, 30, 1860–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Measures Inventory; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2018.

- Chang, A.M.; Cohen, D.; Lin, A.; Augustine, J.; Handel, D.; Howell, E.; Kim, H.; Pines, J.; Schuur, J.D.; McConnell, K.J.; et al. Hospital Strategies for Reducing Emergency Department Crowding: A Mixed-Methods Study. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2018, 71, 497–505.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, M.L.; Zeger, S.L.; Ding, R.; Levin, S.R.; Desmond, J.S.; Lee, J.; Aronsky, D. Crowding Delays Treatment and Lengthens Emergency Department Length of Stay, Even among High-Acuity Patients. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009, 54, 492–503.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonis, J.D.; Aaronson, E.L.; Lee, R.Y.; Philpotts, L.L.; White, B.A. Emergency Department Patient Experience: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Patient Exp. 2018, 5, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Himelic, D.; Arthur, A.O.; Burns, B.; Thomas, S.H. 28 Effects of Emergency Department Operational Parameters on Left without Being Seen: Length of Stay Is Most Important. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2014, 64, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, R.Y.; Sarkar, N.; Shen, Y.-C. Impact of Ambulance Diverison: Black Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction Had Higher Mortality than Whites. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1070–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, R.Y.; Asch, S.M.; Weiss, R.E.; Zingmond, D.; Liang, L.-J.; Han, W.; McCreath, H.; Sun, B.C. California Hospitals Serving Large Minority Populations Were More Likely than Others to Employ Ambulance Diversion. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotoli, J.; Li, T.; Kim, S.; Wu, T.; Hu, J.; Endrizzi, J.; Garton, N.; Jones, C. Emergency Department Testing and Disposition of Deaf American Sign Language Users and Spanish-Speaking Patients. J. Health Disparities Res. Pract. 2020, 13, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Rising, K.L.; Padrez, K.A.; O’Brien, M.; Hollander, J.E.; Carr, B.G.; Shea, J.A. Return Visits to the Emergency Department: The Patient Perspective. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2015, 65, 377–386.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rising, K.L.; Victor, T.W.; Hollander, J.E.; Carr, B.G. Patient Returns to the Emergency Department: The Time-to-Return Curve. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2014, 21, 864–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johns Hopkins University; Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality. Improving the Emergency Department Discharge Process: Environmental Scan Report; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014.

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; ISBN 1-118-62898-5. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, R.M.; Davidson, P.L. Improving Access to Care in America: Individual and Contextual Indicators. In Changing the U.S. Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management; Andersen, R.M., Rice, T.H., Kominski, G.F., Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2007; pp. 3–31. ISBN 978-0-7879-8524-0. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.W.; Kreuter, M. Health Program Planning: An Educational and Ecological Approach, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Boston, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder, L.J.; Aron, D.C.; Keith, R.E.; Kirsh, S.R.; Alexander, J.A.; Lowery, J.C. Fostering Implementation of Health Services Research Findings into Practice: A Consolidated Framework for Advancing Implementation Science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Behr, J.G.; Diaz, R. Emergency Department Frequent Utilization for Non-Emergent Presentments: Results from a Regional Urban Trauma Center Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lines, L.M.; Rosen, A.B.; Ash, A.S. Enhancing Administrative Data to Predict Emergency Department Utilization: The Role of Neighbhorhood Sociodemographics. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2017, 28, 1487–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Green, L.W. Toward Cost-Benefit Evaluations of Health Education: Some Concepts, Methods, and Examples. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 34–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, S.; Lin, X.; Liu, X.Z. Genetics of Hearing and Deafness. Anat. Rec. 2012, 295, 1812–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.R.; White, T.W. Connexin-26 Mutations in Deafness and Skin Disease. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 2009, 11, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, K.L. Rubella in the United States: Toward a Strategy for Disease Control and Elimination. Epidemiol. Infect. 1991, 107, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Menser, M.; Forrest, J.; Bransby, R.; Hudson, J. Longterm Observation of Diabetes and the Congenital Rubella Syndrome in Australia. Clin. Genes. Diabetes Mellit. Excerpta Med. Amst. 1982, 221–225. [Google Scholar]

- Sever, J.L.; South, M.A.; Shaver, K.A. Delayed Manifestations of Congenital Rubella. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1985, 7, S164–S169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G.; Tehranifar, P. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Health Inequalities: Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S28–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Is Racism a Fundamental Cause of Inequalities in Health? Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2015, 41, 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, H.-D.L. Audism: Exploring the Metaphysics of Oppression. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 2004, 9, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamerdinger, S. As I See It. Signs Ment. Health 2018, 15, 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Glickman, N.S.; Hall, W.C. (Eds.) Language Deprivation and Deaf Mental Health; Taylor & Francis Group: Thames, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mauldin, L. Made to Hear: Cochlear Implants and Raising Deaf Children; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4529-4990-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, W.C.; Smith, S.R.; Sutter, E.J.; DeWindt, L.A.; Dye, T.D.V. Considering Parental Hearing Status as a Social Determinant of Deaf Population Health: Insights from Experiences of the “Dinner Table Syndrome". PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Karchmer, M.A. Chasing the Mythical Ten Percent: Parental Hearing Status of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students in the United States. Sign Lang. Stud. 2004, 4, 138–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.E.; Karchmer, M.A. Parental Hearing Status and Signing among Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students. Sign Lang. Stud. 2005, 5, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, P.C.; O’Hearn, A.; McKee, M.; Steider, A.; Thew, D. Deaf Epistemology: Deafhood and Deafness. Am. Ann. Deaf 2010, 154, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Ryan, C.; Smith, S.; Kushalnagar, R. Critical Health Literacy in American Deaf College Students. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 33, 827–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M. Communication in the Doctor’s Office: Deaf Patients Talk about Their Physicians. Ph.D. Thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, N.K.; Hall, W.C.; Henner, J. American Sign Language Interpreters in Public Schools: An Illusion of Inclusion That Perpetuates Language Deprivation. Matern. Child Health J. 2020, 24, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freel, B.L.; Clark, M.D.; Anderson, M.L.; Gilbert, G.L.; Musyoka, M.M.; Hauser, P.C. Deaf Individuals’ Bilingual Abilities: American Sign Language Proficiency, Reading Skills, and Family Characteristics. Psychology 2011, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Visual Language and Visual Learning Science of Learning Center. Advantages of Early Visual Language (Research Brief No. 2); Sharon Baker: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zazove, P.; Meador, H.E.; Reed, B.D.; Gorenflo, D.W. Deaf Persons’ English Reading Levels and Associations with Epidemiological, Educational, and Cultural Factors. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garberoglio, C.L.; Palmer, J.L.; Cawthon, S.; Sales, A. Deaf People and Educational Attainment in the United States: 2019; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Garberoglio, C.L.; Palmer, J.L.; Cawthon, S.; Sales, A. Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes: Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- Engelman, A.; Kushalnagar, P. Food Insecurity, Chronic Disease and Quality of Life among Deaf Adults Who Use American Sign Language. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2021, 16, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Moreland, C.J.; Simons, A.; Holcomb, T. Communication Barrier in Family Linked to Increased Risks for Food Insecurity among Deaf People Who Use American Sign Language. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- James, T.G.; McKee, M.M.; Sullivan, M.K.; Sewell, Z.Y.; Ashton, G.; Hardy, S.J.; Phillips, D.G.; Cheong, J. Health Concerns and Risk Behavior among Deaf People in Florida: A Call for Action. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Society for Public Health Education, Online, 21–25 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.L.; James, T.G.; Barnett, S. Suicidal Behaviors and Help-Seeking Attitudes among Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing College Students. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2019, 50, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Reesman, J.; Holcomb, T.; Ryan, C. Prevalence of Anxiety or Depression Diagnosis in Deaf Adults. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 2019, 24, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, T.S.; Rush, S.; Musich, S.; Nickels, L.; Wu, L.; Yeh, C.S. Impacts of Hearing Loss and Limited Health Literacy among Older Adults. In Proceedings of the IHI National Forum on Quality Improvement in Health Care, Orlando, FL, USA, 9–12 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, M.M.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Winters, P.C.; Fiscella, K.; Zazove, P.; Sen, A.; Pearson, T. Assessing Health Literacy in Deaf American Sign Language Users. J. Health Commun. 2015, 20 (Suppl. 2), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bat-Chava, Y.; Martin, D.; Kosciw, J. Barriers to HIV/AIDS Knowledge and Prevention among Deaf and Hard of Hearing People. AIDS Care 2005, 17, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margellos-Anast, H.; Estarziau, M.; Kaufman, G. Cardiovascular Disease Knowledge among Culturally Deaf Patients in Chicago. Prev. Med. 2006, 42, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.M.; Schlehofer, D.; Cuculick, J.; Starr, M.; Smith, S.; Chin, N.P. Perceptions of Cardiovascular Health in an Underserved Community of Deaf Adults Using American Sign Language. Disabil. Health J. 2011, 4, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orsi, J.M.; Margellos-Anast, H.; Perlman, T.S.; Giloth, B.E.; Whitman, S. Cancer Screening Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors among Culturally Deaf Adults: Implications for Informed Decision Making. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2007, 31, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.G.; Sullivan, M.K.; McKee, M.M.; Hardy, S.J.; Ashton, G.; Santiago Zayas, Z.; Phillips, D.G.; Cheong, J. Conducting Low Cost Community-Engaged Health Research with Deaf American Sign Language Users. PsyArXiv Prepr. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Harris, R.; Paludneviciene, R.; Hoglind, T. Health Information National Trends Survey in American Sign Language (HINTS-ASL): Protocol for the Cultural Adaptation and Linguistic Validation of a National Survey. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2017, 6, e172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McKee, M.M.; Hauser, P.C.; Champlin, S.; Paasche-Orlow, M.; Wyse, K.; Cuculick, J.; Buis, L.R.; Plegue, M.; Sen, A.; Fetters, M.D. Deaf Adults’ Health Literacy and Access to Health Information: Protocol for a Multicenter Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2019, 8, e14889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pollard, R.Q., Jr.; Dean, R.K.; O’Hearn, A.; Haynes, S.L. Adapting Health Education Material for Deaf Audiences. Rehabil. Psychol. 2009, 54, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Naturale, J.; Paludneviciene, R.; Smith, S.R.; Werfel, E.; Doolittle, R.; Jacobs, S.; DeCaro, J. Health Websites: Accessibility and Usability for American Sign Language Users. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zak, A. Lead Found in Water at Michigan School for the Deaf Campus Building. Mich. Radio 2016. Available online: https://www.michiganradio.org/news/2016-01-21/lead-found-in-water-at-michigan-school-for-the-deaf-campus-building (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Zahran, S.; McElmurry, S.P.; Kilgore, P.E.; Mushinski, D.; Press, J.; Love, N.G.; Sadler, R.C.; Swanson, M.S. Assessment of the Legionnaires’ Disease Outbreak in Flint, Michigan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1730–E1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoglind, T.; Simons, A.; Kushalnagar, P. Access Disparity and Health Inequity for Insured Deaf Patients. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association, San Diego, CA, USA, 10–14 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Hill, C.; Carrizales, S.; Sadler, G.R. Prostate-Specimen Antigen (PSA) Screening and Shared Decision Making among Deaf and Hearing Male Patients. J. Cancer Educ. 2020, 35, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Engelman, A.; Simons, A.N. Deaf Women’s Health: Adherence to Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Recommendations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.G.; Sullivan, M.K.; Dumeny, L.; Lindsey, K.; Cheong, J.; Nicolette, G. Health Insurance Literacy and Health Service Utilization among College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.G.; Coady, K.A.; Stacciarini, J.-M.R.; McKee, M.M.; Phillips, D.G.; Maruca, D.; Cheong, J. “They’re Not Willing to Accommodate Deaf Patients”: Communication Experiences of Deaf American Sign Language Users in the Emergency Department. Qual. Health Res. 2021, preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.; Keele, B. Development and Validation of an Instrument to Measure Nurses’ Beliefs towards Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Interaction. J. Nurs. Meas. 2020, 28, E175–E215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M.M.; Barnett, S.; Block, R.C.; Pearson, T.A. Impact of Communication on Preventive Services among Deaf American Sign Language Users. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steinberg, A.G.; Barnett, S.; Meador, H.E.; Wiggins, E.A.; Zazove, P. Health Care System Accessibility: Experiences and Perceptions of Deaf People. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lutz, B.J.; Hall, A.G.; Vanhille, S.B.; Jones, A.L.; Schumacher, J.R.; Hendry, P.; Harman, J.S.; Carden, D.L. A Framework Illustrating Care-Seeking among Older Adults in a Hospital Emergency Department. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.A.; Rising, K.L.; Jones, J.; Bowden, M.L.; Ginde, A.A.; Havranek, E.P. Reasons Patients Choose the Emergency Department Ovder Primary Care: A Qualitative Metasynthesis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 2610–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uscher-Pines, L.; Pines, J.; Kellermann, A.; Gillen, E.; Mehrotra, A. Deciding to Visit the Emergency Department for Non-Urgent Conditions: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Am. J. Manag. Care 2013, 19, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Pines, J.M.; Lotrecchiano, G.R.; Zocchi, M.S.; Lazar, D.; Leedekerken, J.B.; Margolis, G.S.; Carr, B.G. A Conceptual Model for Episodes of Acute, Unscheduled Care. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2016, 68, 484–491.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigun, A.C.; Maguire, K.; Jiang, Y.; Qu, H.; Austin, S. Urgent Care Center and Emergency Department Utilization for Non-Emergent Health Conditions: Analysis of Managed Care Beneficiaries. Popul. Health Manag. 2019, 22, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, L.M.; Boudreaux, E.D.; Chimowitz, H.; Liu, G.; Cyr, E.; Kimball, E. What Do Emergency Department Physicians and Nurses Feel? A Qualitative Study of Emotions, Triggers, Regulation Strategies, and Effects on Patient Care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2020, 29, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbell, L.M.; Tager, J.; Beals, K.; Liu, G. Emotionally Evocative Patients in the Emergency Department: A Mixed Methods Investigation of Providers’ Reported Emotions and Implications for Patient Safety. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2020, 29, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liese, V. Indian River County Hospital District; 2012; Vol. Case No. 10-15968. [Google Scholar]

- Yabe, M. Healthcare Providers’ and Deaf Patients’ Interpreting Preferences for Critical Care and Non-Critical Care: Video Remote Interpreting. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 13, 100870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Paludneviciene, R.; Kushalnagar, R. Video Remote Interpreting Technology in Healthcare: Cross-Sectional Study of Deaf Patients’ Experiences. JMIR Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2019, 6, e13233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendergrass, K.M.; Nemeth, L.; Newman, S.D.; Jenkins, C.M.; Jones, E.G. Nurse Practitioner Perceptions of Barriers and Facilitators in Providing Health Care for Deaf American Sign Language Users: A Qualitative Socio-ecological Approach. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healthcare Research and Quality Act of 1999; 1999; Volume 113, p. 1653.

- Mertens, D.M. Transformative Paradigm: Mixed Methods and Social Justice. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D.M. What Does a Transformative Lens Bring to Credible Evidence in Mixed Methods Evaluations? New Dir. Eval. 2013, 138, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, O.E.; Henner, J. The Personal Is Political in The Deaf Mute Howls: Deaf Epistemology Seeks Disability Justice. Disabil. Soc. 2017, 32, 1416–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, M.M.; Schlehofer, D.; Thew, D. Ethical Issues in Conducting Research with Deaf Populations. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 2174–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, C. When the Hearing World Will Not Listen: Deaf Community Care in Hearing-Dominated Healthcare. Master’s Thesis, Boston University, Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Meek, D. Dinner Table Syndrome: A Phenomenological Study of Deaf Individuals’ Experiences with Inaccessible Communication. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 1676–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V. Baptist Health South Florida, Inc. 2017; Vol. Case No. 16-10094. [Google Scholar]

- Ngai, K.M.; Grudzen, C.R.; Lee, R.; Tong, V.Y.; Richardson, L.D.; Fernandez, A. The Association between Limited English Proficiency and Unplanned Emergency Department Revisit within 72 Hours. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2016, 68, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, W.C. What You Don’t Know Can Hurt You: The Risk of Language Deprivation by Impairing Sign Langauge Development in Deaf Children. Matern. Child Health J. 2017, 21, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hall, W.C.; Levin, L.L.; Anderson, M.L. Language Deprivation Syndrome: A Possible Neurodevelopmental Disorder with Sociocultural Origins. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kushalnagar, P.; Reesman, J. Linking Evidence with Practice: Language Deprivation, Communication Neglect, and Health Outcomes. In Proceedings of the 2019 American Deafness and Rehabilitation Association/Association of Medical Professionals with Hearing Losses Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 1–3 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E.G.; Renger, R.; Kang, Y. Self-Efficacy for Health-Related Behaviors among Deaf Adults. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.; Kim, D.S.; Mika, V.H.; Imran Ayaz, S.; Millis, S.R.; Dunne, R.; Levy, P.D. Emergency Department Visits in Patients with Low Acuity Conditions: Factors Associated with Resource Utilization. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaf World; Bragg, L. (Ed.) New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-8147-9853-9. [Google Scholar]

- Guttman, N.; Nelson, M.S.; Zimmerman, D.R. When the Visit to the Emergency Department Is Medically Nonurgent: Provider Ideologies and Patient Advice. Qual. Health Res. 2001, 11, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, S.E.; Schumacher, J.R.; Hall, A.G.; Hendry, P.; Peltzer-Jones, J.M.; Kalynych, C.; Carden, D.L. Primary Care Experiences of Emergency Department Patients with Limited Health Literacy. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2016, 39, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sunderland v. Bethesda Health, Inc. 2016; Case No. 13-80685-CIV-HURLEY; p. 1344.

- Panzer, K.; Park, J.; Pertz, L.; McKee, M.M. Teaming Together to Care for Our Deaf Patients: Insights from the Deaf Health Clinic. JADARA 2020, 53, 60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Standard Practice Paper: Use of a Certified Deaf Interpreter; Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, A.G.; Sullivan, V.J.; Loew, R.C. Cultural and Linguistic Barriers to Mental Health Service Access: The Deaf Consumer’s Perspective. AJP 1998, 155, 982–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Deakyne, S.; Bajaj, L.; Roosevelt, G.E. Comparison of Throughput Times for Limited English Proficiency Patient Visits in the Emergency Department between Different Interpreter Modalities. J. Immigr. Minority Health 2012, 14, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Sanchez, A.; Ma, M. The Impact of Patient-Provider Race/Ethnicity Concordance on Provider Visits: Updated Evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2019, 6, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.K.; Pollard, R.Q., Jr. The Demand Control Schema: Interpreting as a Practice Profession, 1st ed.; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: North Charleston, SC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4895-0219-3. [Google Scholar]

- Decision-Making Processes of Patients Who Use the Emergency Department for Primary Care Needs. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2013, 24, 1288–1305. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planey, A.M. Audiologist Availability and Supply in the United States: A Multi-Scale Spatial and Political Economic Analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 222, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. 1990. Available online: https://www.ada.gov/pubs/adastatute08.htm (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Rehabilitation Act of 1973. 1973. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/USCODE-2010-title29/pdf/USCODE-2010-title29-chap4-sec31.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2019).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

James, T.G.; Varnes, J.R.; Sullivan, M.K.; Cheong, J.; Pearson, T.A.; Yurasek, A.M.; Miller, M.D.; McKee, M.M. Conceptual Model of Emergency Department Utilization among Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Patients: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412901

James TG, Varnes JR, Sullivan MK, Cheong J, Pearson TA, Yurasek AM, Miller MD, McKee MM. Conceptual Model of Emergency Department Utilization among Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Patients: A Critical Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(24):12901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412901

Chicago/Turabian StyleJames, Tyler G., Julia R. Varnes, Meagan K. Sullivan, JeeWon Cheong, Thomas A. Pearson, Ali M. Yurasek, M. David Miller, and Michael M. McKee. 2021. "Conceptual Model of Emergency Department Utilization among Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Patients: A Critical Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 24: 12901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412901

APA StyleJames, T. G., Varnes, J. R., Sullivan, M. K., Cheong, J., Pearson, T. A., Yurasek, A. M., Miller, M. D., & McKee, M. M. (2021). Conceptual Model of Emergency Department Utilization among Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Patients: A Critical Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 12901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412901