1. Introduction

The agricultural sector continues to be strategic in the development of developing nations in Africa, where smallholder farming is the dominant livelihood activity. The agricultural sector in South Africa accounts for around 2.3% of the country’s GDP, 40% of export earnings, and 4.6% of employment in the country [

1]. In South Africa, Statistics South Africa (StatSA) [

1] showed that 13.8% (2.33 million) of all the households are agricultural households, many of them situated in rural areas. Smallholder agriculture provides about 70% of the employment in rural households and serves as the main source of income [

2]. Smallholder agriculture plays a vital role in food security, job creation, and reasonable distribution of income, poverty alleviation, and linkage creation for economic growth [

3,

4,

5]. The agricultural sector has proven to be the backbone of improvement of rural food security and livelihoods in the country [

6]. However, the sector is facing numerous challenges, such as insufficient access to technology, institutional difficulties, inappropriate policies, poor infrastructure, and unsuccessful links to the markets, which make it difficult for smallholder farmers to participate in the formal market sector [

7]. In South Africa, there are two types of marketing (formal and informal). Formal marketing involves the formal movement of crops through a different chain of factors, such as seed producers, crop growers, distributors, merchants, and agro-dealers, while informal marketing involves the decentralized market distribution where smallholder farmers sell or exchange crops directly with other farmers, neighbours, or local communities. Smallholder farmers produce traditional crops more for consumption, and they depend on informal markets to sell their surpluses due to inadequate linkages with formal markets [

8]. This emphasizes the need to reconsider policies and institutions that support smallholder agricultural participation in the formal markets.

Market participation holds significant potential for revealing suitable opportunity sets necessary for providing better incomes and sustainable livelihoods for smallholder farmers [

9,

10,

11]. Facilitating the development of market participation by smallholder farmers can be important in helping households to alleviate food poverty and food insecurity [

12,

13]. It can also enable smallholder farmers to have access to affordable production inputs; hence, this will ensure that farmers are not trapped in low productivity–low return farming activities that lead to food vulnerability. The use of better-quality inputs will improve the ability of smallholder farmers to produce enough marketable surplus and subsequently leads to a better market orientation of goods produced by farmers [

14]. The need for developing smallholder market participation has been progressively recognized in efforts to achieve agricultural transformation in developing countries [

15]. However, smallholder farmers, particularly in South Africa, are faced with several barriers preventing them from gaining access to markets and productive assets.

Many of the smallholder farmers in South Africa are currently inactive participants, often obliged to sell low (immediately after harvest) and buy high; with little information on where to conduct transactions, they end up being price takers [

16]. The constraints affecting smallholder farmers in market participation can be classified as technical, institutional, and socio-demographic factors [

16]. Smallholder farmers are living in remote areas with poorly maintained roads and market infrastructure, inadequate transport and storage facilities, and lack of skills and information, which cause high transaction costs of market participation [

17,

18]. Farmers mainly produce for consumption and sell the surplus to their local communities; the small surplus they produce prevents them from participating in a competitive market and exposes them to high risks and transaction costs that limit them to a non-contestable market dominated by a few powerful buyers [

19]. They are faced with incapacities to have contractual agreements, low access to extension agents, poor organizational support, low use of improved seed, and low use of fertilizer, all of which also make it difficult for farmers to commercialize [

20]. Other factors that affect farmers’ participation include household size, age and education, source of income, marital status, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status of household members. The impact of HIV on agriculture is very important, as it results in a decline in agricultural production [

21]. HIV affects the number of workers available for agricultural activities, leading to low production and productivity, and thus reduces the food stocks that could potentially be taken to the market as part of the outputs for smallholder farmers. The HIV pandemic has an effect on both national development and household economies, which worsens poverty and inequalities [

22]. It increases the mortality rate of young and most productive people, which affects smallholder agriculture since it is labour intensive [

23]. The epidemic worsens inequalities, poverty, and reduces labour productivity and supply, which slows economic growth [

21]. Furthermore, when these conditions get worse, they in turn make households even more at risk and vulnerable to the epidemic. Therefore, it is important to prioritize the improvement of smallholder agriculture to increase the economic activities of smallholder farmers so they can competitively participate in the market. Provision of support by government, policymakers, and other stakeholders can improve the productivity and profitability of smallholder farmers.

Research has been done on market participation in different parts of developing countries such as South Africa. Several studies have been conducted on market participation involving livestock farming, such as cattle and goats [

24,

25,

26]; other studies considered constraints to market participation [

18,

27,

28,

29]. However, there is limited knowledge on the participation of smallholder farmers in the market within the South African context. It is against this backdrop that this study sought to understand the typology of the level of market participation among the smallholder farmers in South Africa. The study attempted to fill the research gap and contribute to the generation of evidence for policymakers to realize the inequalities that still exist in the market of South Africa and the need to review existing policies. Therefore, the study generated new empirical information on the simultaneous interaction of household decisions of market participation and the most influential factors on the market participation of smallholder farmers in South Africa.

2. Literature Review on Factors Affecting Market Participation by Smallholder Farmers in Developing Countries

Marketing is a formalized system that can be directed from seed producer to farmer, or via a chain of actors including distributors, merchants, and agro-dealers until the end user [

30]. Marketing aims to identify, anticipate, and satisfy the need of customers and to achieve the objectives of suppliers [

31]. To smallholder farmers, marketing means selling or exchanging what they produce on the farm to other farmers, neighbours, or the local community. To a retailer, marketing means promoting goods and services to their consumers. Markets play an important role in production, as they act as a mechanism for exchange. Market participation by smallholder farmers is essential, as it results in the coordination and efficient use of resources, goods, and services [

27]. It allows smallholder farmers to derive benefits such as income and accessible opportunities for rural employment [

27]. In addition, the involvement of farmers in the market sector can expose rural households to other market activities, such as transportation, processing, and selling, which can employ those who are not willing to participate in the farming sector [

29]. In developing countries such as South Africa, market participation can promote sustainable agriculture and economic growth and can also lessen poverty and inequality. Unfortunately, smallholder farmers face difficulties in accessing markets, and as a result, markets fail to effectively perform their duty, which is to provide profits and income to smallholder farmers.

There are several determinants of market participation of smallholder farmers, which can be categorized as institutional, technical, and socio-demographic factors. It is essential to this paper to identify the constraints that smallholder farmers face within market participation. The institutional factors include transaction costs, contractual arrangements, inappropriate policies, and markets information flows. Many studies conducted in the rural economies of developing countries confirmed that smallholder farmers lack adequate market information and contractual arrangements that allow them to formally participate in the market [

18,

27,

28,

32]. These factors result in high transaction costs and may cause farmers to either stop participating in the market or lead them to participate in informal markets [

32,

33]. Jari and Fraser [

17] revealed that in the Eastern Cape Province in the South Africa market, information, expertise on grades and standards, contractual agreements, social capital, market infrastructure, group participation, and tradition significantly influenced household marketing behaviour. Many farmers did not participate in the market because they lacked market information, expertise on grade and standards, and contractual agreements. This was substantiated by Sebatta et al. [

18], who found that smallholder farmers in Uganda failed to access market information due to remoteness and lack of access to market arrangements, which affected their decision to enter the potato market to sell. The study also found that few farmers were visited by extension officers who provided information on market availability as well as information on new and improved varieties that enhanced the farmer’s knowledge and provided a range and choice of market opportunities. This indicates the level of inequality in service deliveries among farmers in rural areas.

Technical factors are those factors that allow input and output on the market to be accessible at lower costs and that allow diversification of markets. These factors are typically influenced by organization, regulations, and improvements in technology [

17]. The factors include market transportation facilities, road infrastructure, household asset holdings, telecommunication networks, storage facilities, and access to extension services. In South Africa, many smallholder farmers live in remote areas where there are limited services, such as poor road infrastructure, storage and transportation facilities, and communication links, and they have limited capacity to add value to their produce [

34]. Omiti et al. [

28] conducted a study on factors affecting market participation by smallholder farmers in rural and peri-urban areas. The results showed that farmers in peri-urban areas sold higher proportions of their output than those in rural areas. This was because of the distance from farm to the market, poor market information, and poor roads experienced by farmers in the rural areas, which affected their sales. These findings were supported by Zamasiya et al. [

35] who found that ownership of radios, television, and cell phones improved access to market information and had a positive effect on the household’s decision to participate in the soybean market in Zimbabwe.

Household asset holdings can help to alleviate any production and market shocks that smallholder farmers experience. Assets such as land, livestock, and human capital and farm implements are crucial for marketable surplus production at a smallholder level [

36]. In South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, almost 60% of rural households own less than 1 ha of farmland, and approximately 80% of the rural households have less than 2 ha of farmland [

37]. Farmers owning small farms may not be able to raise the necessary surplus to sell at the market [

38]. South Africa is faced with an increasing population, which causes a decline in per capita farm sizes, especially in rural areas. This influences their ability to feed themselves and their families and to sell the surplus in the market. Smallholder farmers with more land can produce more of the crops, and they can be able to expand their production to ensure sustainable supply to the market. Osmani and Hossain [

34] found that smallholder farmers with adequate land, household labour, and farm income had a moderate level of participation in the market, and they had 57% sales in their produced crops. It can be said that holding farm assets can enable smallholder farmers to exercise economies of scale by adopting modern technologies [

39].

The socio-demographic factors that affect smallholder farmers’ participation in the markets can include household head age, marital status, household size, source of labour, education, and gender. Farming in rural areas is mostly dominated by women, who are involved in subsistence agriculture. Rural women are an essential resource in agriculture and the rural economy in developing countries [

40]. They often manage multifaceted households, provide agricultural labour force, and pursue multiple livelihood strategies. However, female farmers grow subsistence crops mainly for household consumption, and cash crops that are meant to provide income are mainly grown by male farmers [

41]. Sebatta et al. [

18] showed that females were less likely to participate in the process of selling potatoes in Uganda. Related to that, Vargas Hill and Vigneri [

41] found that in Uganda, female farmers sold coffee in the same market as male farmers; however, females significantly got lower prices for the same coffee. Furthermore, Kyaw et al. [

42] conducted a study on farmers participation in the rice markets in the central dry zone of Myanmar, the results revealed that 77% of the market participants were male, while 23% were female. On the contrary, Zamasiya et al. [

35] found that in Zimbabwe, male-headed households were less likely than female-headed households to participate in soybean markets. The study concluded that this was because legumes are believed to be women’s crops in developing countries. These findings indicate that even in farming there is still gender inequality and that the role of female farmers is underrated.

In South Africa, most of the smallholder farmers are old and not educated; they rely more on their traditions, which make them reluctant to adopt modern technologies that will improve their participation in the market [

43]. Participation in the market declines with age, as older farmers are more susceptible to risk aversion and conservative attitudes [

44,

45]. It can be said that education can empower a farmer to make informed decisions and to be able to identify market opportunities. Sebatta et al. [

18] and Adeoti et al. [

46] found from their studies that in Uganda and Nigeria, farmers’ educational status showed a positive relationship with market participation. Marital status affects farmers’ market participation differently: Egbetokun and Omonona [

47] identified marital status as a major factor that influences participation in markets and reported a positive and significant impact in Nigeria. Contrarily, Adeoye and Adegbite [

48] stated a significant but negative effect of marital status on participation in markets. Nwafor [

49] found that in Nigeria, 80% of married farmers participated in the market, and 20% did not participate. All the results obtained in the different studies show that more training and workshops need to be conducted in rural areas to increase market participation of farmers, taking into consideration the constraints they are faced with.

All the constraints mentioned above results in high transaction costs, which prevent farmers from getting meaningful benefits from their trading activities, thus discouraging farmers from marketing activities. Smallholder farmers operate under informal production systems, and they depend on traditional social networks and mechanisms for marketing their produce. Most smallholder farmers use barter, traditional labour payment, or gifts to exchange or obtain seeds and crops [

50]. Most of their produce exchange takes place within the community, between members within the same social class and ethnic group. Most of the smallholder farmers are price takers and do not have much power to influence market decisions. Monyo and Bänziger [

51] stated that more than 90% of farmers’ necessities are met through these informal channels. There is an urgent need to strengthen market information delivery systems, upgrade roads, encourage market integration initiatives, and establish more retail outlets with improved market facilities in the remote rural areas to promote production and trade in high-value commodities by rural farmers. Therefore, analysis of the factors affecting the market participation decision of smallholder farmers will help to design appropriate policy instruments, institutions, and other interventions for their sustainable economic development. It can be concluded that more research is needed to provide evidence-based information for policy and government interventions.

3. Research Methodology

The data used in this research were part of a larger baseline assessment study that was conducted in the different provinces in South Africa in 2016 to obtain a comprehensive understanding of livelihood systems and to determine the extent of food and nutrition insecurity. This study focused on two provinces of South Africa (Limpopo and Mpumalanga). The two provinces are populated by smallholder communal farmers who mainly depend on agricultural and livestock farming for their livelihoods. Moreover, the two provinces have relatively more smallholder farmers participating in the market. Although the data were collected in 2016, the findings based on these data are still relevant and very important in improving the situation of the smallholder farmers regarding their participation in the market. The insights drawn from the findings based on these data are still important and critical to enhancing the existing literature. Considering that these data are reported at the household level whilst other national datasets, such as the General Household Survey conducted by Statistics South Africa, are aggregated at a provincial level to form representation, the findings based on these data are relevant for the government and policymakers because the findings can inform policy and programme interventions at a household level. No other comprehensive agricultural, food, and nutrition security dataset that is representative at a household level has been collected in the country so far. In addition, the government, as a custodian of these data, therefore has an interest in what comes out from the data in terms of policy and programme recommendations. Permission to use this dataset was granted by the government, suggesting their willingness to see these data being used to help inform better programming based on evidence.

The study used a quantitative research method to collect data. Data on key agricultural, food, and nutrition security indicators were collected from a household sample drawn using a multi-stage stratified random sampling technique to collect quantitative information through a survey on 3 districts of Limpopo and 4 districts of Mpumalanga. The multi-stage stratified technique is a random sampling process that allows individuals in a certain population to have an equal and independent chance of being selected [

52]. This technique was used because it is quite easy to implement, cheap to use, and it requires the least knowledge of the population to be sampled. It also allows large sampling, as large samples are accurate in the representation of the population, while smaller samples produce less accurate results, and they are likely to be less representative of the population. In each site, the livelihood of the population, including farmers, was divided into strata based on similar characteristics or variables (socio-economic characteristics, outputs, sales, household sizes, and institutional factors). The populations of the Livelihood Zones (geographical areas in which people broadly share similar patterns of livelihoods) produced by the South African Vulnerability Assessment Committee (SAVAC) in 2014 were used as the assessment’s sample frame. Accordingly, the current study used these data as secondary data, which were collected by the SAVAC, led by the Secretariat hosted in the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform, and Rural Development (DALRRD) in 2016. A total of 1520 respondents were selected from two provinces (Limpopo and Mpumalanga).

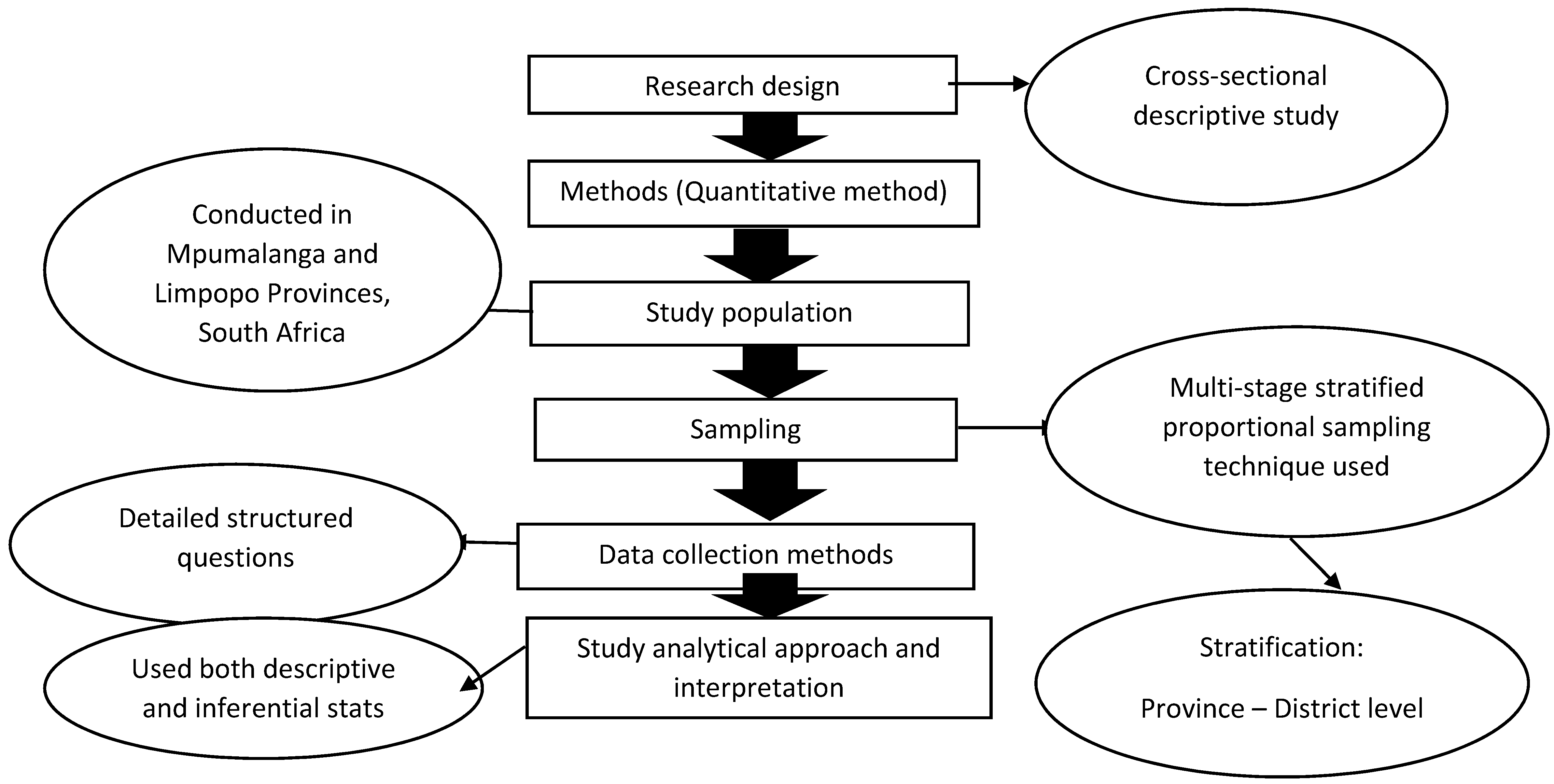

Figure 1 shows a summary of how the research was designed and its procedures.

The data were captured in a computerized manner using Statistical Packages for Social Science (SPSS) (IBM, 2014). The marketing decision of crop farmers was modelled as a two-step decision process: (1) the household decides whether or not to participate in the market and (2) the household decides on the volume of crops to be marketed. The double-hurdle model Cragg [

53] cited by Achandi and Mujawamariya [

38] was used to model this two-step decision process, following numerous other market participation studies [

38,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58]. This model was chosen over the Heckman sample selection model, which has been used by many studies [

18,

34,

42,

45,

59]. The Heckman method addresses the statistical challenge posed by cases in which market sales equal zero as a missing data problem. However, when considering the issue of zero market sales, representing a zero amount of maize output sold as a missing value is not a valid economic choice for a model to explain [

54]. The double-hurdle model produces estimates that are superior to the Heckman model when one is dealing with true zeros.

According to the double-hurdle model, a farmer faces two hurdles while deciding on market participation: whether or not to participate in the market and how much of their crop to sell in the market. With the assumption of the error terms in the equations being conditionally uncorrelated on all covariates, the standard errors from separate estimations are also valid for conducting statistical inference. If the conditionally uncorrelated errors assumption does not hold, coefficient estimates from separate regressions will be biased [

60]. According to Wooldridge [

61], testing for conditionally uncorrelated errors follows the same method as does the Heckman test for selection bias. Although it is not technically necessary for identification, it is standard to impose at least one justifiable exclusion restriction when estimating the second stage. The null hypothesis that the first and second stage errors are conditionally uncorrelated is tested using the standard

t-statistic for the coefficient estimate on inverse mill ration (

IMR). If the coefficient estimate is statistically significantly different than zero, we reject the null hypothesis and the model must be re-estimated to conduct valid inference [

62]. If we fail to reject the null, we re-estimate second-stage parameters excluding

IMR.

The variables in the first equation of dependent variables were estimated using the probit model. The probit model accounts for the clustering of zeros due to non-participation, and it is used to predict the probability of whether smallholder farmers participate in the market [

45].

The double-hurdle model is stated as:

where

is an indicator variable equal to unity for smallholder farmers that participated in the market.

is the quantity of crop sales made by smallholder farmer

iThe participation equation can then be written as:

where

is the latent level of utility farmers get from participating in the market, and

ε is the error term.

The binary model is then stated as:

In exact terms, the probit model in stage one of estimation is stated as:

where,

is the probability of a smallholder farmer making a decision to sell crops in the market,

is a constant,

…

βn are parameters to be estimated,

….

are the vector of explanatory variables identified in

Table 1, and

ε is an error term.

In the second step, an additional regressor in the sales equation will be included to correct for potential selection bias. This regressor is the inverse Mills ratio (IMR). The IMR is computed as Equation (6):

where

φ is the normal probability density function. The second-stage equation is given by Equation (7):

where

E is the expectation operator,

Y is the (continuous) proportion of rice sold,

x is a vector of independent variables affecting the quantity of rice sold, and

β is the vector of the corresponding coefficients to be estimated. The extent of participation is indicated by:

where

is the number of crops marketed,

is a vector of covariates that explains this amount,

β is a vector of unobserved parameters to be estimated, and

Vi is a random variable indicating all other factors apart from

X.

Count data are non-normal and hence are not well estimated by ordinary least squares (OLS) regression [

63]. The most common regression models used to analyse count data models include the Poisson regression model (PRM), the negative binomial regression model (NBRM), the zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP), and the zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB). The PRM and NBRM regression models have become the standard models for the analysis of response variables with non-negative integers [

64]. The PRM and ZIP models were used in this study because diagnostic tests revealed the absence of overdispersion and under dispersion. Following Wooldridge [

61] and Greene [

64], the density function of the Poisson regression model is given by:

where

and

, 1…

is the number of crops sold by farmers, while

is the vector of predictor variables and

and

are the parameters to be estimated. Greene (2003; 2008) shows that the expected number of events

(in this case, number of crops sold by farmers) is given as;

Empirical Estimation Procedure and Hypothesis Testing

Estimation of the model outlined above in Equations (1) to (10) followed a series of regression diagnostics. Variables used in both stages of the model were first checked for normality using exploratory data analysis using the coefficient of kurtosis and skewness. To correct for selectivity bias, an inverse Mills ratio (IMR) predicted from the first-hurdle equation was used as a covariate in the count data model (second-hurdle).

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

The involvement of smallholder farmers in marketing can play a critical role in meeting their goals, such as food and nutrition security, poverty alleviation, and sustainable agriculture. This study found that the market participation and sales ratio of smallholder farmers are constrained by numerous factors, such as socioeconomic, market, and institutional factors. Smallholder farmer’s market participation was affected by factors such as education level, the gender of the household, salary of household, and agricultural assistance. The results reveal that household size, household age, and HIV status of a member of a family as well as agricultural assistance, marital status, and educational level had significant influences on the level of market participation.

Agricultural extension and advisory services have a considerable contribution to economic and social development, including the facilitation of smallholder farmer development. This, therefore, suggests that in order to develop smallholder farmers and improve their market participation, there is a need to offer quality extension and advisory services. The government need to improve the performance of agricultural extension services in South Africa. More capable and qualified extension workers need to be hired and trained in marketing so that the marketing of produce is part and parcel of their message delivery in their advisory duties to farmers. Generally, smallholder farmers do not get agricultural assistance and market information because they are not formally registered: they exist in non-homogenous groups, while the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform, and Rural Development is faced with budget constraints. It is recommended that the government, extension workers, and policymakers encourage organized smallholder farmers into groups so that they can help them in large numbers at the same time. When the farmers are organized, the services from the government can be coordinated better, as appointed committee members could be responsible for accessing those services on behalf of the whole group. Government should support the smallholder farmers through the provision of training that is sensitive to the fact that they are generally uneducated; therefore, the information should be packaged in a way that is easy for them to comprehend. To improve smallholder farmers’ production and productivity, the government also need to ensure that their support is timely and well-targeted to those who most need it. Intensive programmes are needed to encourage youth to participate in agriculture, as most young people are literate and can therefore easily grasp the marketing information. Much attention and support need to be given towards women’s involvement in market participation, and women also need to be empowered by the government and other interested stakeholders to fully participate in the decision making related to the price of their produce and where to sell it. More workshops especially for young people and women need to be conducted in rural areas to raise awareness of the importance of agriculture.

In light of these findings, the government and policymakers must revise their agricultural marketing policies and redo policies that will favour the conditions under which smallholder farmers live and operate. Government need to follow-up on policy implementation so that accessibilities to markets and sales of crops can improve.