FedHGPrompt: Privacy-Preserving Federated Prompt Learning for Few-Shot Heterogeneous Graph Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We formally define the problem of federated few-shot learning on heterogeneous graphs and establish a comprehensive threat model with clear privacy objectives.

- We propose FedHGPrompt, the first framework that seamlessly integrates heterogeneous graph prompt learning with a secure aggregation protocol, enabling privacy-preserving and communication-efficient collaborative learning.

- We provide a detailed privacy analysis, demonstrating that our framework protects individual client updates under standard cryptographic assumptions, even in the presence of client dropouts and collusion.

- Through extensive experiments on three public heterogeneous graph datasets (ACM, DBLP, and Freebase), we validate that FedHGPrompt significantly outperforms existing federated graph learning baselines—including both standard federated GNNs and a concurrent federated graph prompt method—in few-shot scenarios while maintaining robust privacy.

2. Related Work

2.1. Graph Representation Learning: From Homogeneous to Heterogeneous Graphs

2.2. Prompt Learning on Graphs

2.3. Federated Learning on Graphs

2.4. Secure Aggregation in Federated Learning

2.5. Summary and Positioning

3. Preliminaries and Problem Statement

3.1. Graph Representation and Few-Shot Learning Background

3.1.1. Heterogeneous Graph Formalization

3.1.2. Few-Shot Learning on Graphs

3.1.3. Graph Neural Networks and Prompt Learning

3.2. Federated Learning System Architecture

3.2.1. System Participants and Data Distribution

3.2.2. Federated Training Process

3.2.3. Global Learning Objective

3.2.4. Communication and Aggregation Mechanism

3.3. Threat Model and Security Objectives

3.3.1. Adversarial Capabilities and Assumptions

- 1.

- Honest-but-Curious (Passive) Adversaries:

- All protocol participants, including the server and clients, adhere strictly to the prescribed protocol steps without deviation.

- However, adversaries may attempt to infer sensitive information about other participants’ private data by analyzing all messages exchanged during protocol execution.

- We allow for collusion among up to clients and the server, where these entities may pool their views to enhance inference capabilities.

- The pre-trained model and global prompts are considered public knowledge, as they are distributed to all clients.

- 2.

- Active (Malicious) Adversaries:

- Adversaries may arbitrarily deviate from the protocol specification to achieve their objectives.

- The server may drop, modify, delay, or inject fabricated messages to disrupt training or extract private information.

- Malicious clients may submit malformed or manipulated updates to compromise model integrity or launch poisoning attacks.

- Clients may drop out unexpectedly during protocol execution due to network failures or adversarial behavior.

- We assume the existence of a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) that enables authentication of messages, preventing the server from impersonating legitimate clients.

3.3.2. Privacy and Security Goals

3.3.3. Differential Privacy Considerations

4. Methodology

4.1. System Architecture Overview

- (a)

- Pre-training phase: A graph neural network (GNN) model is first pre-trained on the server using available graph data. This phase produces a powerful and general-purpose frozen GNN backbone model , which serves as a shared feature extractor for all subsequent federated tasks. No prompt vectors are involved at this stage.

- (b)

- Federated learning phase: This is the core adaptive learning stage. The pre-trained backbone is distributed to all clients and remains fixed. The federated learning process focuses on optimizing a set of lightweight, learnable prompt vectors , which are initialized at the start of this phase. The process unfolds as follows:

- Local Adaptation with Dual Templates: On each client, the private heterogeneous graph is unified via a Graph Template, and the few-shot task is formulated via a Task Template.

- Prompt Tuning: Clients adapt the global prompts locally by tuning them on their private few-shot support sets. Only the prompts () are updated, keeping the backbone frozen.

- Secure Aggregation: The server collects and securely aggregates the local prompt updates to obtain a refined global prompt set , ensuring no leakage of individual client data.

4.2. Graph Unification via Dual Templates

4.2.1. Graph Structure Template

- preserves the complete graph topology without type distinctions, capturing the overall connectivity patterns.

- For each node type , with and , representing the subgraph induced by nodes of type t and edges between them.

4.2.2. Task Formulation Template

- For node-level tasks, is the -hop neighborhood subgraph centered at node v.

- For graph-level tasks, (the entire graph).

- 1.

- Link Prediction: Given a positive edge and a negative candidate , the objective becomeswhere is a similarity function (e.g., cosine similarity).

- 2.

- Node Classification: For a node v with class label c, we construct class prototypes as the average embedding of support nodes from class c,where is the support set and K is the number of shots. The classification rule is

- 3.

- Graph Classification: Similarly to node classification, but operating on graph-level embeddings and graph class prototypes.

4.3. Federated Prompt Learning Formulation

4.3.1. Problem Formalization

4.3.2. Dual-Prompt Design: Feature and Heterogeneity Prompts

4.3.3. Federated Aggregation Mechanism

- 1.

- Global Prompt Broadcast: The server distributes the current global prompt vectors to all participating clients.

- 2.

- Client Local Update: Each client performs local training on its private data to compute prompt updates,where is obtained by minimizing on for E local epochs.

- 3.

- Secure Aggregation: Clients participate in a secure aggregation protocol that computes the weighted sum of updates without revealing individual contributions,where is the set of clients participating in round t, and are normalized weights based on dataset sizes.

- 4.

- Global Prompt Update: The server updates the global prompts,where is a global learning rate.

4.4. Algorithmic Components

4.4.1. Client Local Prompt Training Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Client Local Prompt Training |

|

4.4.2. Server-Side Prompt Aggregation Algorithm

| Algorithm 2 Server-Side Prompt Aggregation |

|

4.4.3. Secure Aggregation Protocol

| Algorithm 3 Secure Aggregation Protocol |

|

4.5. Privacy and Security Analysis

- 1.

- Hybrid 0: Real protocol execution.

- 2.

- Hybrid 1: Replace Diffie–Hellman shared secrets with random values. Indistinguishable under the DDH assumption.

- 3.

- Hybrid 2: Replace encrypted shares with encryptions of zeros. Indistinguishable under IND-CPA security of authenticated encryption.

- 4.

- Hybrid 3: For honest clients not in the coalition, replace their self-mask shares with shares of zero. Indistinguishable due to Shamir secret sharing properties when the coalition has fewer than t shares.

- 5.

- Hybrid 4: Replace PRG outputs with truly random vectors. Indistinguishable under PRG security.

- 6.

- Hybrid 5: Replace masked updates with random values conditioned on their sum equaling the aggregated result. Indistinguishable due to the pairwise mask structure (Lemma 1 in [14]).

4.6. Communication Complexity Analysis

- Round 1: for sending public keys and signatures.

- Round 2: where d is the prompt dimension and N is the number of clients. The term comes from transmitting the masked update vector, while comes from sending encrypted shares to other clients.

- Round 3: for sending the consistency signature.

- Round 4: for responding to share requests.

4.7. Computational Complexity Analysis

5. Experiments

5.1. Experimental Settings

5.1.1. Datasets and Data Partitioning

- ACM is a paper–author–subject graph where nodes represent papers, authors, and topics. Edges capture “writes” and “about” relations. The task is to classify papers into research fields (Database, Wireless Communication, Data Mining).

- DBLP is an author–paper–venue graph for scientific publication networks. Each author is classified into one of four domains (Database, AI, Networking, Theory).

- Freebase is a large-scale knowledge graph with 8 node types and 36 relation types, containing entities such as films, actors, and writers. The classification task predicts the domain of entities.

5.1.2. Baseline Methods

Centralized Learning Methods

- GCN [15]: A classic homogeneous graph convolutional network.

- GAT [16]: Graph attention network with attention-based neighborhood aggregation.

- HAN [2]: Heterogeneous graph attention network using meta-path-based attention.

- Simple-HGN [3]: A simplified heterogeneous GNN with learnable edge type embeddings.

- GraphPrompt [5]: A prompt learning framework for homogeneous graphs.

- HGPrompt [7]: The state-of-the-art heterogeneous graph prompt learning framework.

Federated Learning Methods

- FedGCN: Federated GCN using FedAvg [1] aggregation.

- FedGAT: Federated GAT using FedAvg aggregation.

- FedHAN: Federated HAN with meta-path-based aggregation.

- FedSimple-HGN: Federated version of Simple-HGN.

- FedGraphPrompt: Federated adaptation of GraphPrompt using FedAvg.

- FedGPL [13]: A concurrent federated graph prompt learning framework.

Privacy-Preserving Federated Methods

- FedHGPrompt-DP: Our framework with differential privacy (Gaussian noise added before secure aggregation).

- FedHGPrompt-SA: Our framework with secure aggregation only (no differential privacy).

5.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Micro-F1: The F1 score computed globally by counting total true positives, false negatives, and false positives across all classes.

- Macro-F1: The average of per-class F1 scores, giving equal weight to each class regardless of its size.

5.1.4. Implementation Details

Pre-Training

Federated Training

Secure Aggregation

Differential Privacy

5.2. Main Results

5.2.1. Performance Comparison with Centralized Methods

- 1.

- FedHGPrompt achieves competitive performance compared to centralized methods, despite each client having access to only K-shot labeled data while centralized methods have access to labeled examples. For example, on the ACM dataset with shot per client ( clients), FedHGPrompt achieves 77.3% Micro-F1, which is only 2.3% lower than centralized HGPrompt with 5-shot per class (79.6%).

- 2.

- Heterogeneous graph methods (HAN, Simple-HGN, HGPrompt) consistently outperform homogeneous graph methods (GCN, GAT, GraphPrompt) across all datasets, confirming the importance of modeling graph heterogeneity.

- 3.

- Prompt-based methods (GraphPrompt, HGPrompt) outperform traditional supervised methods (GCN, GAT, HAN, Simple-HGN), highlighting the effectiveness of prompt learning in few-shot scenarios.

- 4.

- The performance gap between centralized HGPrompt and federated FedHGPrompt is relatively small (1.9-2.5% across datasets), demonstrating that federated learning with secure aggregation can achieve comparable performance to centralized training while preserving data privacy.

5.2.2. Performance Comparison with Federated Methods

- 1.

- FedHGPrompt significantly outperforms all other federated methods across all datasets and metrics. For instance, on DBLP, FedHGPrompt achieves 84.2% Micro-F1, which is 3.4% higher than the second-best method, FedGPL (80.8%).

- 2.

- The superiority of FedHGPrompt over FedGraphPrompt demonstrates the importance of handling graph heterogeneity through the dual-template and dual-prompt design.

- 3.

- Even when incorporating differential privacy (FedHGPrompt-DP), our method maintains competitive performance with only a slight degradation (1.0–1.5% across datasets), showing the robustness of our framework to privacy-preserving noise.

- 4.

- Traditional federated methods (FedGCN, FedGAT) perform poorly in the few-shot setting, highlighting the challenge of learning from limited labeled data in decentralized environments.

5.2.3. Efficiency Analysis: Communication and Computational Overhead

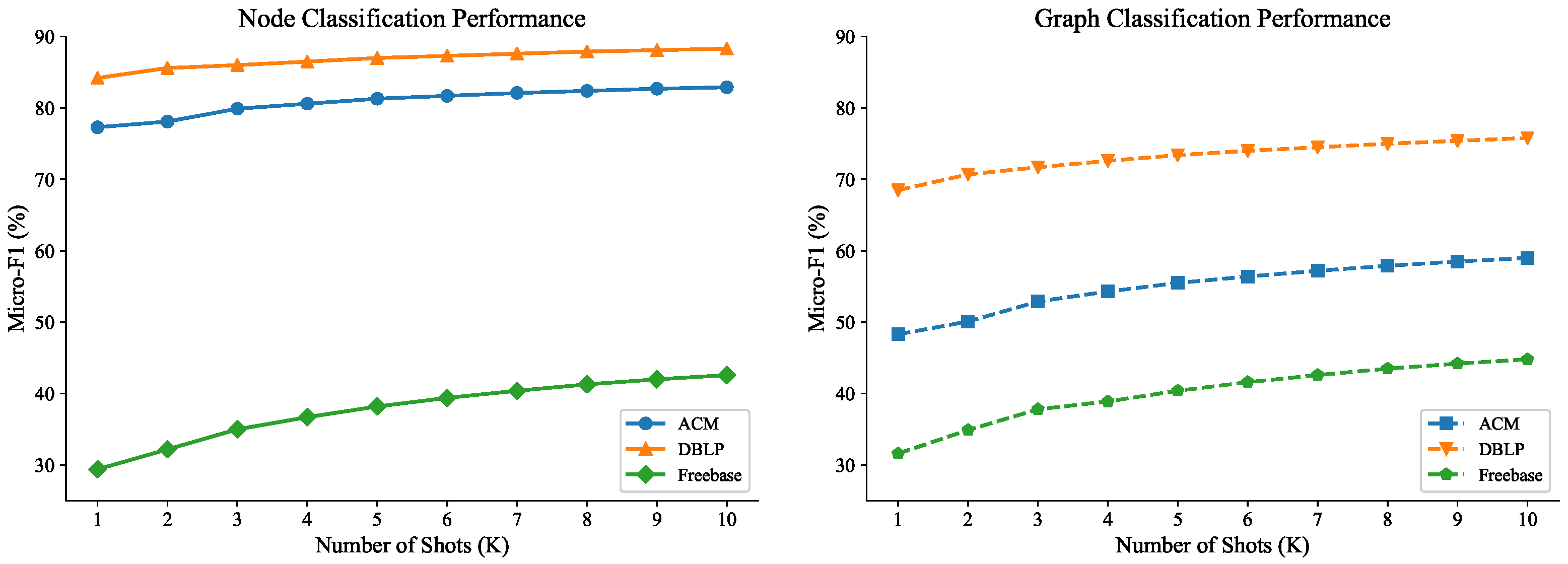

5.2.4. Effect of Number of Shots K

- 1.

- Strong Marginal Utility Diminishing Effect: Across all datasets and tasks, performance improvements show clear diminishing returns as K increases. The most substantial gains occur from to , with progressively smaller improvements thereafter. By , additional shots provide minimal benefits (e.g., for ACM node classification: :77.3%, :81.3%, :82.9%).

- 2.

- Optimal Shot Range: The data suggests that to represents the optimal range for FedHGPrompt. Beyond , the performance gains become negligible relative to the increased labeling cost. This finding is particularly important for practical applications where labeling resources are limited.

- 3.

- Practical Implication for Federated Learning: In federated settings where each client may have limited labeled data, our results suggest that collecting 3–5 shots per class per client is sufficient. This makes FedHGPrompt highly suitable for real-world applications where centralized collection of large labeled datasets is impractical or privacy-prohibitive.

5.2.5. Effect of Privacy Parameters

5.3. Ablation Study

- 1.

- Graph Template is Essential: Removing the graph template causes the largest performance degradation across all datasets (19.1%/19.0%/8.6% drop for ACM, DBLP and Freebase node classification). This substantial impact demonstrates that unifying heterogeneous graphs into homogeneous views is fundamental for effective federated learning on heterogeneous data.

- 2.

- Task Template Provides Major Benefits: The task template contributes significantly to performance (14.6%/12.9%/5.8% drop for ACM/DBLP/Freebase node classification). Reformulating diverse tasks into a unified subgraph similarity framework enables better knowledge transfer and adaptation in few-shot federated settings.

- 3.

- Dual-Prompt Components are Valuable: Both feature and heterogeneity prompts substantially improve performance (7.2%/6.3%/2.9% and 5.8%/4.6%/2.3% drops, respectively, for ACM/DBLP/Freebase node classification). Their complementary roles adapt models to feature variations and heterogeneity differences across client tasks.

5.4. Discussion

- 1.

- Effectiveness: FedHGPrompt significantly outperforms existing federated methods, achieving performance close to centralized training while preserving data privacy.

- 2.

- Efficiency: The framework maintains reasonable communication costs, making it suitable for practical deployment.

- 3.

- Privacy: Secure aggregation and optional differential privacy provide strong protection against privacy attacks with minimal performance degradation.

- 4.

- Robustness: The framework performs well across different datasets, shot numbers, and client counts, demonstrating its general applicability.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; PMLR: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Ji, H.; Shi, C.; Wang, B.; Ye, Y.; Cui, P.; Yu, P.S. Heterogeneous graph attention network. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 2022–2032. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Q.; Ding, M.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Feng, W.; He, S.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, J.; Dong, Y.; Tang, J. Are we really making much progress? revisiting, benchmarking and refining heterogeneous graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual Event, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 1150–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, B.; Liu, G.; Han, C.; Jiang, M.; Ji, H.; Han, J. Large language models on graphs: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 8622–8642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, X. Graphprompt: Unifying pre-training and downstream tasks for graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Liu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, X. Generalized graph prompt: Toward a unification of pre-training and downstream tasks on graphs. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2024, 36, 6237–6250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Hgprompt: Bridging homogeneous and heterogeneous graphs for few-shot prompt learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 16578–16586. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, P.; Ma, B.; Zhou, J.; Ruan, Z.; Chen, G.; Xuan, Q. Sampling subgraph network with application to graph classification. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 3478–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Xiong, L.; Yang, C. Federated node classification over graphs with latent link-type heterogeneity. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, Austin, TX, USA, 30 April–4 May 2023; pp. 556–566. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; He, X.; Yu, G.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Domeniconi, C. Personalized federated few-shot node classification. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2025, 68, 112105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Huang, W.; Ye, M. Federated graph learning under domain shift with generalizable prototypes. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024; Volume 38, pp. 15429–15437. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.; Tang, J.; Yin, D.; Chawla, N.; Huang, C. A survey of large language models for graphs. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 6616–6626. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Han, R.; Liu, H. Against multifaceted graph heterogeneity via asymmetric federated prompt learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.02003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonawitz, K.; Ivanov, V.; Kreuter, B.; Marcedone, A.; McMahan, H.B.; Patel, S.; Ramage, D.; Segal, A.; Seth, K. Practical secure aggregation for privacy-preserving machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2017; pp. 1175–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Velicković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. Stat 2017, 1050, 10–48550. [Google Scholar]

- Velicković, P.; Fedus, W.; Hamilton, W.L.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y.; Hjelm, R.D. Deep graph infomax. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1809.10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Chen, T.; Sui, Y.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z.; Shen, Y. Graph contrastive learning with augmentations. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 5812–5823. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Lu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Shi, C. Contrastive pre-training of GNNs on heterogeneous graphs. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual Event, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 803–812. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Liu, N.; Han, H.; Shi, C. Self-supervised heterogeneous graph neural network with co-contrastive learning. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual Event, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 1726–1736. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.; Xie, C.; Duan, H.; Yu, B. NoiseHGNN: Synthesized similarity graph-based neural network for noised heterogeneous graph representation learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–29 February 2025; Volume 39, pp. 21725–21733. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.W.; Xiong, B.; Yang, C.; Ho, J.C. Hypmix: Hyperbolic representation learning for graphs with mixed hierarchical and non-hierarchical structures. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Boise, ID, USA, 21–25 October 2024; pp. 3852–3856. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.; Zhou, K.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Gppt: Graph pre-training and prompt tuning to generalize graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022; pp. 1717–1727. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Fang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wen, Z.; Bo, J.; Zhang, X.; Hoi, S.C.H. A survey of few-shot learning on graphs: From meta-learning to pre-training and prompt learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.01440. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhou, C.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, X. Multigprompt for multi-task pre-training and prompting on graphs. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2024, Singapore, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 515–526. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, V.; Bruna, J. Few-shot learning with graph neural networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.04043. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Cai, F.; Zheng, J.; Pan, Z.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H. Information bottleneck-driven prompt on graphs for unifying downstream few-shot classification tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2025, 62, 104092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Li, C.; Long, R.; Yan, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhuang, W.; Yin, J.; Zhang, P.; Han, W.; Sun, H.; et al. A comprehensive study on text-attributed graphs: Benchmarking and rethinking. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 17238–17264. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.; Sun, L.; Yu, P.S.; Wang, Z. Decentralized Federated Learning: A Survey and Perspective. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 34617–34638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruccio, L.; Cimino, G.; Deufemia, V.; Iuliano, G.; Stanzione, R. Surveying federated learning approaches through a multi-criteria categorization. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 36921–36951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, G.; Jiang, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, C. Federated learning on non-iid graphs via structural knowledge sharing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 9953–9961. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; Li, P.; Miyazaki, T.; Wu, C. Fedgraph: Federated graph learning with intelligent sampling. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2021, 33, 1775–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, X.; Qi, J.; Jin, H.; Yang, P.; Shen, S.; Wang, C. Fedgs: Federated graph-based sampling with arbitrary client availability. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 10271–10278. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, L.; Li, D.; Jiang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. FCGNN: Fuzzy cognitive graph neural networks with concept evolution for few-shot learning. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 34, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Xu, H.; Liao, H.; Zhou, Y. Seaflame: Communication-efficient secure aggregation for federated learning against malicious entities. IACR Trans. Cryptogr. Hardw. Embed. Syst. 2025, 2025, 69–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmaka, I.; Phuong, T.V.X. One-shot secure aggregation: A hybrid cryptographic protocol for private federated learning in IoT. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.23252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Joshi, J.B.D.; Ma, S.; Li, J. Tapfed: Threshold secure aggregation for privacy-preserving federated learning. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 21, 4309–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Mao, Y.; He, X.; Huang, H.; Wu, J. Balancing privacy and accuracy using significant gradient protection in federated learning. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2025, 74, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, S.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J. DP-FedCMRS: Privacy-preserving federated learning algorithm to solve heterogeneous data. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 41984–41993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiello, R.; Gritti, C.; Önen, M.; Lorenzi, M. Buffalo: A practical secure aggregation protocol for buffered asynchronous federated learning. In Proceedings of the Fifteenth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, Virtual Event, 18–20 June 2024; pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Gai, K. RaSA: Robust and adaptive secure aggregation for edge-assisted hierarchical federated learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 4280–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Fang, Y.; Shi, C. Learning to pre-train graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Event, 2–9 February 2021; Volume 35, pp. 4276–4284. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Graph Type | Learning Paradigm | Few-Shot | Federated | Privacy Guarantee | Prompt-Based |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GCN [15] | Homo. | Supervised | × | × | × | × |

| GAT [16] | Homo. | Supervised | × | × | × | × |

| HAN [2] | Hetero. | Supervised | × | × | × | × |

| Simple-HGN [3] | Hetero. | Supervised | × | × | × | × |

| GraphPrompt [5] | Homo. | Pre-train + Prompt | ✓ | × | × | ✓ |

| Di-Graph [27] | Homo. | Pre-train + Prompt | ✓ | × | × | ✓ |

| HGPrompt [7] | Hetero. | Pre-train + Prompt | ✓ | × | × | ✓ |

| FCGNN [34] | Homo./Hetero. | FL | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| FedPANO [10] | Hetero. | Personalized FL | ✓ | ✓ | × | × |

| FedGPL [13] | Hetero. | Pre-train + Prompt + FL | ✓ | ✓ | × * | ✓ |

| FedHGPrompt | Hetero. | Pre-train + Prompt + FL | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Dataset | Nodes | Edges | NodeTypes | RelTypes | Classes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACM | 10.9k | 547.9k | 4 | 8 | 3 |

| DBLP | 26.1k | 239.6k | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| Freebase | 180.1k | 1057.7k | 8 | 36 | 7 |

| Setting | Method | ACM | DBLP | Freebase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | ||

| Centralized | GCN | 58.7 ± 2.8 | 52.4 ± 3.2 | 59.5 ± 3.1 | 56.1 ± 3.5 | 25.6 ± 3.2 | 23.2 ± 3.6 |

| GAT | 46.2 ± 3.1 | 36.8 ± 3.5 | 73.2 ± 2.7 | 71.0 ± 3.0 | 26.5 ± 3.0 | 25.1 ± 3.4 | |

| HAN | 70.5 ± 2.3 | 65.8 ± 2.6 | 70.8 ± 2.5 | 68.9 ± 2.8 | 27.3 ± 2.8 | 25.6 ± 3.1 | |

| Simple-HGN | 53.8 ± 2.9 | 49.1 ± 3.3 | 68.0 ± 2.8 | 65.5 ± 3.1 | 26.5 ± 2.9 | 24.8 ± 3.3 | |

| GraphPrompt | 73.9 ± 2.1 | 69.8 ± 2.4 | 81.8 ± 1.9 | 77.6 ± 2.2 | 28.5 ± 2.6 | 27.0 ± 2.9 | |

| HGPrompt | 79.6 ± 1.8 | 75.2 ± 2.0 | 85.9 ± 1.6 | 81.8 ± 1.9 | 30.8 ± 2.3 | 29.1 ± 2.6 | |

| Federated | FedHGPrompt | 77.3 ± 1.9 | 73.5 ± 2.2 | 84.2 ± 1.7 | 80.6 ± 2.0 | 29.4 ± 2.4 | 28.0 ± 2.7 |

| Method | ACM | DBLP | Freebase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | |

| FedGCN | 54.8 ± 3.2 | 49.2 ± 3.6 | 57.5 ± 3.4 | 54.3 ± 3.8 | 24.2 ± 3.5 | 22.1 ± 3.9 |

| FedGAT | 44.3 ± 3.5 | 35.6 ± 3.9 | 70.5 ± 3.0 | 68.8 ± 3.3 | 25.3 ± 3.3 | 24.0 ± 3.7 |

| FedHAN | 67.8 ± 2.6 | 63.5 ± 3.0 | 69.2 ± 2.8 | 67.4 ± 3.1 | 26.1 ± 3.1 | 24.5 ± 3.5 |

| FedSimple-HGN | 51.2 ± 3.1 | 47.3 ± 3.5 | 66.8 ± 3.0 | 64.6 ± 3.3 | 25.2 ± 3.2 | 23.6 ± 3.6 |

| FedGraphPrompt | 70.9 ± 2.4 | 67.3 ± 2.8 | 79.5 ± 2.2 | 76.1 ± 2.5 | 27.3 ± 2.9 | 26.1 ± 3.2 |

| FedGPL | 72.5 ± 2.3 | 68.9 ± 2.7 | 80.8 ± 2.1 | 77.6 ± 2.4 | 28.1 ± 2.8 | 26.9 ± 3.1 |

| FedHGPrompt | 77.3 ± 1.9 | 73.5 ± 2.2 | 84.2 ± 1.7 | 80.6 ± 2.0 | 29.4 ± 2.4 | 28.0 ± 2.7 |

| FedHGPrompt-DP | 75.8 ± 2.0 | 72.1 ± 2.3 | 82.9 ± 1.8 | 79.3 ± 2.1 | 28.6 ± 2.5 | 27.3 ± 2.8 |

| Method | ACM | DBLP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | |

| FedGCN | 40.2 ± 3.8 | 25.4 ± 4.2 | 45.3 ± 3.6 | 42.1 ± 4.0 |

| FedGAT | 40.1 ± 3.9 | 24.8 ± 4.3 | 53.2 ± 3.4 | 47.5 ± 3.8 |

| FedHAN | 43.0 ± 3.5 | 30.5 ± 3.9 | 54.8 ± 3.2 | 49.8 ± 3.6 |

| FedSimple-HGN | 40.8 ± 3.7 | 25.1 ± 4.1 | 52.1 ± 3.5 | 46.9 ± 3.9 |

| FedGraphPrompt | 44.8 ± 3.4 | 35.2 ± 3.8 | 64.3 ± 3.0 | 56.9 ± 3.4 |

| FedGPL | 45.6 ± 3.3 | 36.1 ± 3.7 | 65.8 ± 2.9 | 58.3 ± 3.3 |

| FedHGPrompt | 48.3 ± 3.1 | 39.8 ± 3.5 | 68.5 ± 2.7 | 61.2 ± 3.1 |

| Method | Communication (KB) | Relative Time | Micro-F1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FedGCN | 410.2 | 0.95 | 54.8 |

| FedGAT | 436.8 | 0.98 | 44.3 |

| FedHAN | 1650.5 | 1.25 | 67.8 |

| FedSimple-HGN | 1845.3 | 1.30 | 51.2 |

| FedGraphPrompt | 1.0 | 0.92 | 70.9 |

| FedGPL | 40.8 | 1.02 | 72.5 |

| FedHGPrompt (plain) | 1.1 | 1.00 | 77.3 |

| FedHGPrompt-SA | 8.5 | 1.12 | 77.2 |

| Method | ACM | DBLP | Freebase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | |

| FedHGPrompt (full) | 77.3 ± 1.9 | 73.5 ± 2.2 | 84.2 ± 1.7 | 80.6 ± 2.0 | 29.4 ± 2.4 | 28.0 ± 2.7 |

| w/o Graph Template | 58.2 ± 3.2 | 54.3 ± 3.6 | 65.8 ± 2.9 | 62.5 ± 3.2 | 20.8 ± 3.3 | 19.5 ± 3.6 |

| w/o Task Template | 62.7 ± 2.8 | 58.9 ± 3.2 | 71.3 ± 2.5 | 67.9 ± 2.8 | 23.6 ± 3.0 | 22.4 ± 3.3 |

| w/o Feature Prompt | 70.1 ± 2.3 | 66.4 ± 2.7 | 77.9 ± 2.1 | 74.5 ± 2.4 | 26.5 ± 2.7 | 25.2 ± 3.0 |

| w/o Heterogeneity Prompt | 71.5 ± 2.2 | 67.8 ± 2.6 | 79.6 ± 2.0 | 76.3 ± 2.3 | 27.1 ± 2.6 | 25.9 ± 2.9 |

| w/o Secure Aggregation | 77.1 ± 1.9 | 73.3 ± 2.2 | 84.0 ± 1.7 | 80.4 ± 2.0 | 29.2 ± 2.4 | 27.8 ± 2.7 |

| FedHGPrompt-DP | 74.6 ± 2.1 | 70.9 ± 2.4 | 81.5 ± 1.9 | 78.0 ± 2.2 | 27.9 ± 2.6 | 26.6 ± 2.9 |

| Method | ACM | DBLP | Freebase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | Micro-F1 | Macro-F1 | |

| FedHGPrompt (full) | 48.3 ± 3.1 | 39.8 ± 3.5 | 68.5 ± 2.7 | 61.2 ± 3.1 | 31.6 ± 3.2 | 29.8 ± 3.5 |

| w/o Graph Template | 32.1 ± 4.2 | 23.5 ± 4.6 | 51.3 ± 3.7 | 43.2 ± 4.1 | 21.4 ± 4.0 | 19.8 ± 4.3 |

| w/o Task Template | 37.5 ± 3.8 | 29.1 ± 4.2 | 57.8 ± 3.4 | 50.1 ± 3.8 | 25.3 ± 3.7 | 23.7 ± 4.0 |

| w/o Feature Prompt | 43.2 ± 3.4 | 35.0 ± 3.8 | 63.1 ± 3.0 | 55.8 ± 3.4 | 28.9 ± 3.4 | 27.3 ± 3.7 |

| w/o Heterogeneity Prompt | 44.6 ± 3.3 | 36.4 ± 3.7 | 64.5 ± 2.9 | 57.3 ± 3.3 | 29.8 ± 3.3 | 28.2 ± 3.6 |

| w/o Secure Aggregation | 48.4 ± 3.1 | 39.8 ± 3.5 | 68.6 ± 2.7 | 61.2 ± 3.1 | 31.5 ± 3.2 | 29.7 ± 3.5 |

| FedHGPrompt-DP | 45.9 ± 3.3 | 37.7 ± 3.7 | 65.8 ± 2.9 | 58.6 ± 3.3 | 30.1 ± 3.3 | 28.5 ± 3.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, X.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X. FedHGPrompt: Privacy-Preserving Federated Prompt Learning for Few-Shot Heterogeneous Graph Learning. Entropy 2026, 28, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28020143

Wu X, Shi J, Zhang X. FedHGPrompt: Privacy-Preserving Federated Prompt Learning for Few-Shot Heterogeneous Graph Learning. Entropy. 2026; 28(2):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28020143

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Xijun, Jianjun Shi, and Xinming Zhang. 2026. "FedHGPrompt: Privacy-Preserving Federated Prompt Learning for Few-Shot Heterogeneous Graph Learning" Entropy 28, no. 2: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28020143

APA StyleWu, X., Shi, J., & Zhang, X. (2026). FedHGPrompt: Privacy-Preserving Federated Prompt Learning for Few-Shot Heterogeneous Graph Learning. Entropy, 28(2), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28020143