Machine Learning the Decoherence Property of Superconducting and Semiconductor Quantum Devices from Graph Connectivity

Abstract

1. Introduction

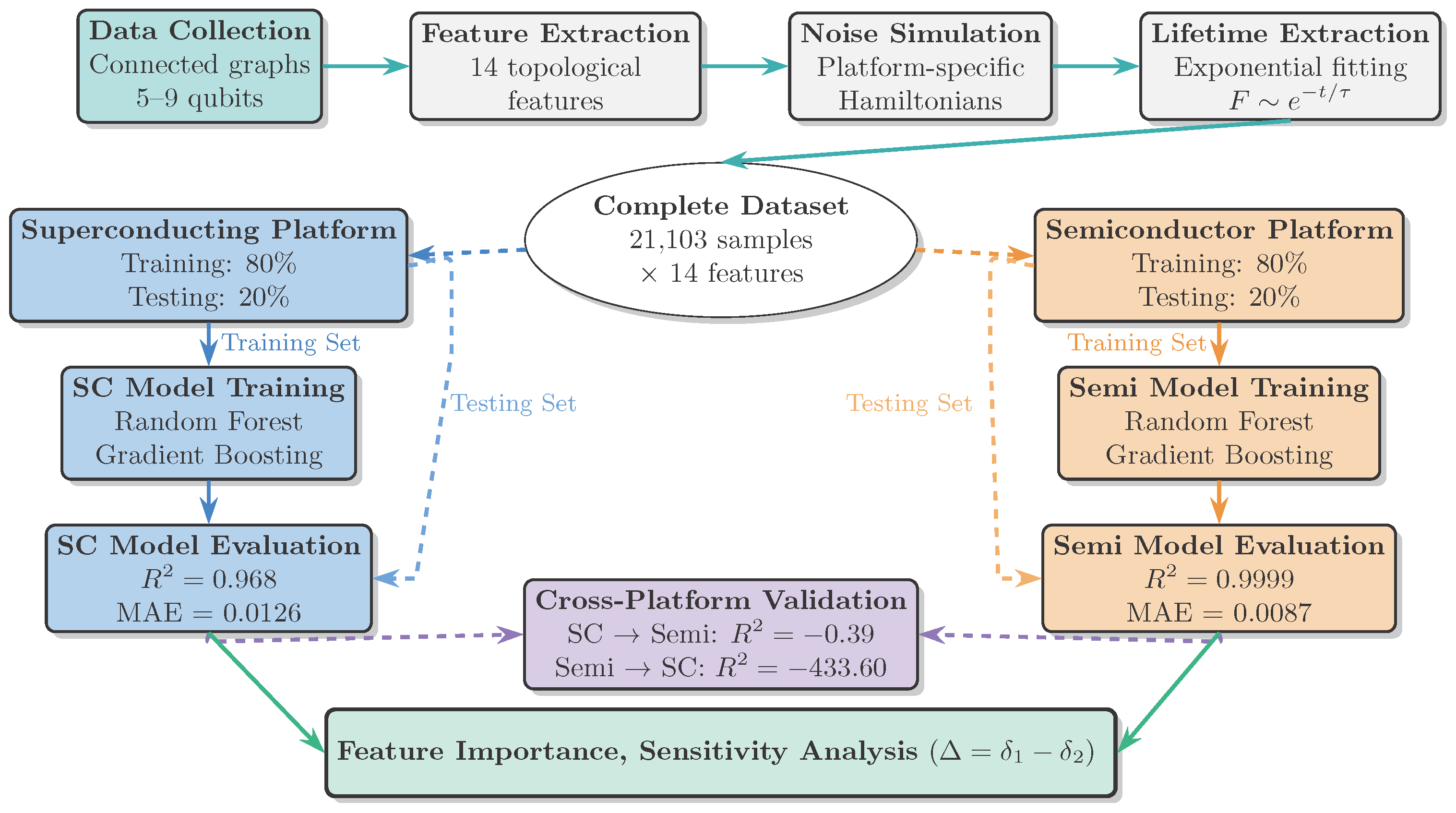

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

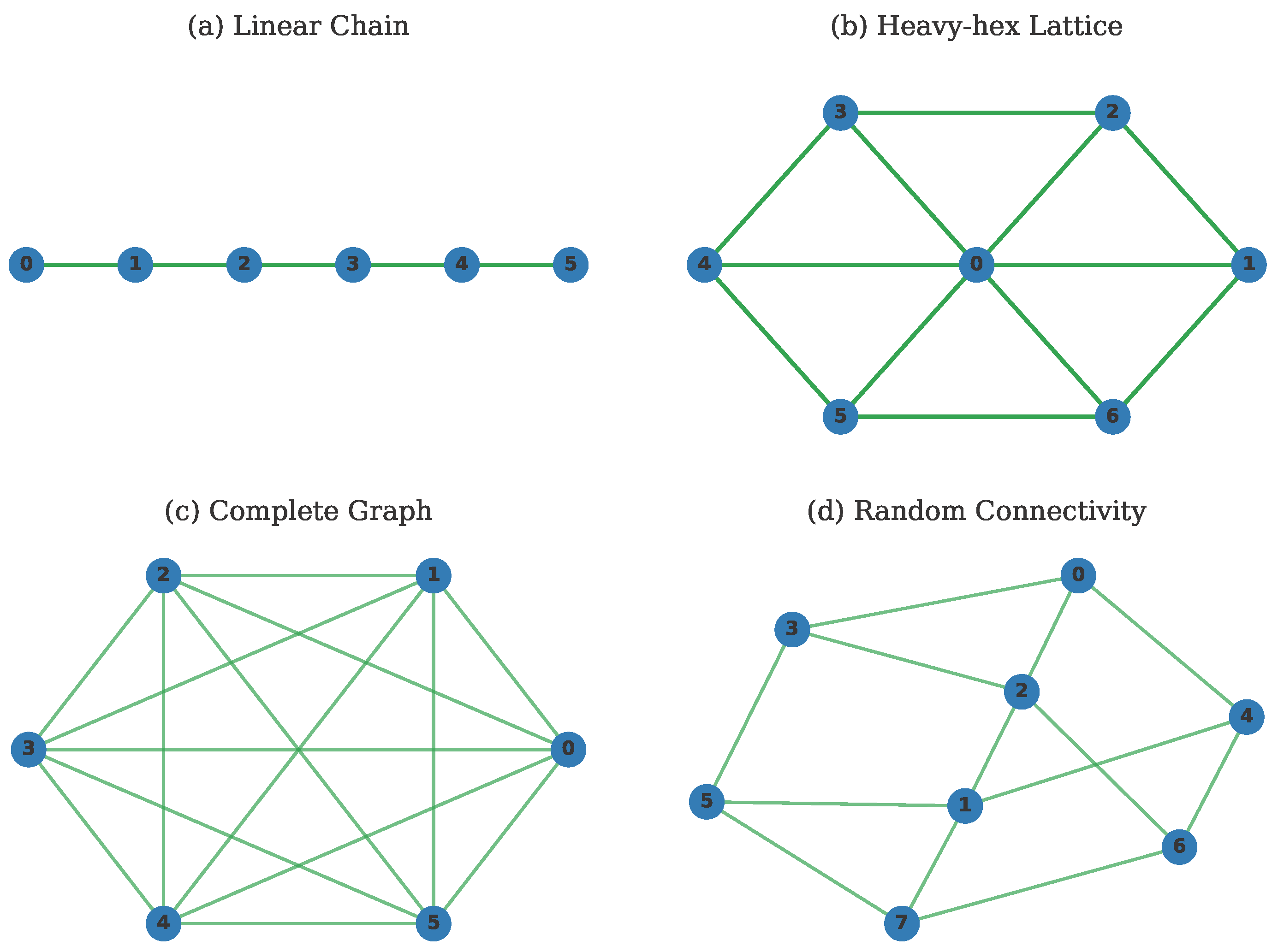

2.1. Graph Representation and Topological Feature Set

2.2. Decoherence Metric and Noise Models

3. Machine Learning Methodology

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Supervised Learning Performance Comparison

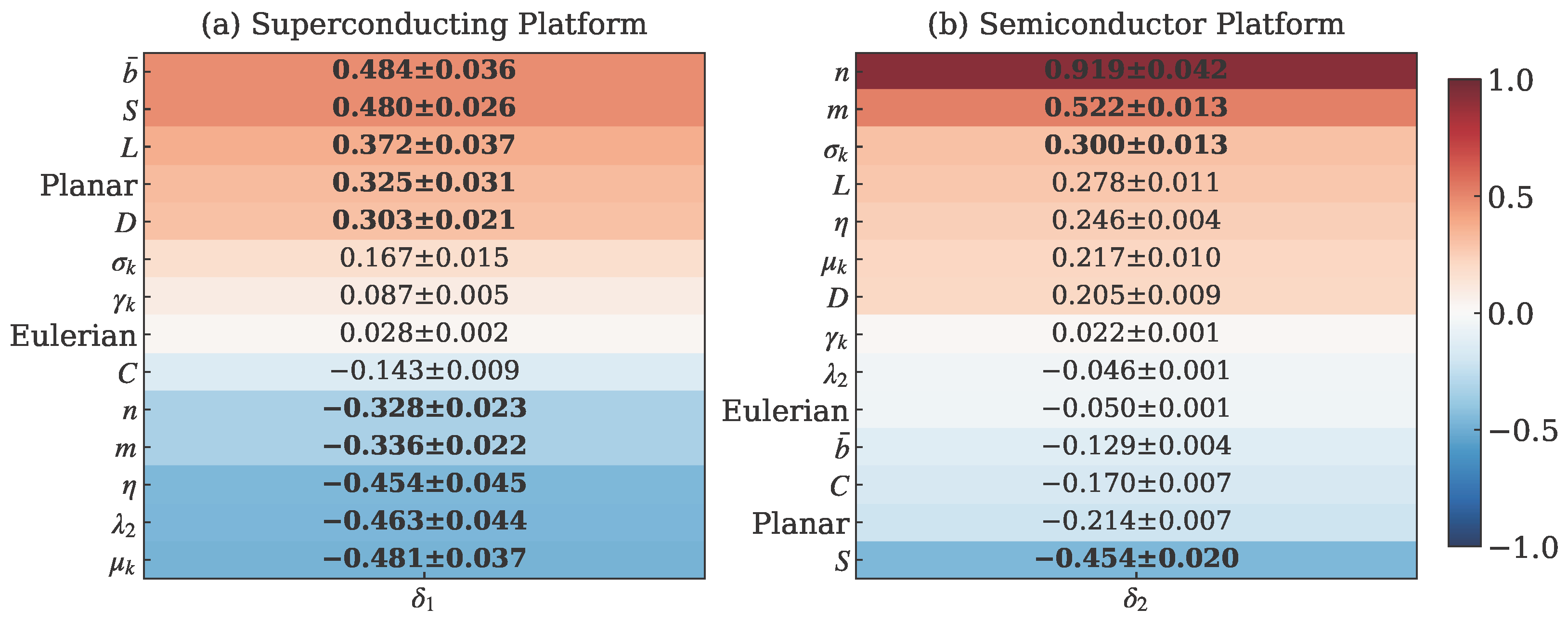

4.2. Platform-Specific Correlation Analysis and Sensitivity Differences

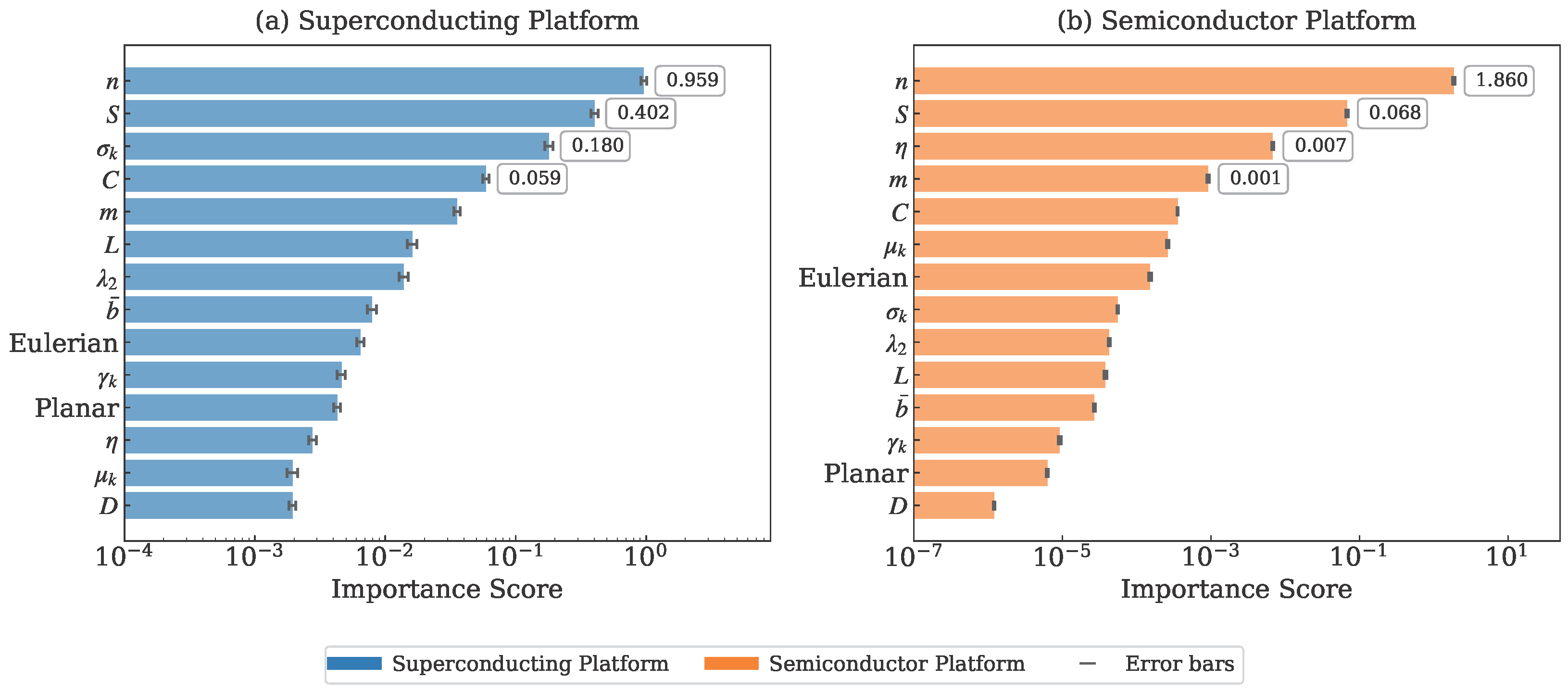

4.3. Feature Importance Rankings and Platform Specificity

4.4. Cross-Platform Generalization Analysis

4.5. Design Implications and Optimization Guidelines

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, A.; Ambainis, A.; Augustino, B.; Bärtschi, A.; Buhrman, H.; Coffrin, C.; Cortiana, G.; Dunjko, V.; Egger, D.J.; Elmegreen, B.G.; et al. Challenges and opportunities in quantum optimization. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2024, 6, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonaiuto, G.; Gargiulo, F.; De Pietro, G.; Esposito, M.; Pota, M. Best practices for portfolio optimization by quantum computing, experimented on real quantum devices. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Vedula, P. Trajectory optimization using quantum computing. J. Glob. Optim. 2019, 75, 199–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.L.; Munro, W.J.; Kendon, V.M. Using Quantum Computers for Quantum Simulation. Entropy 2010, 12, 2268–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Stoudenmire, E.M.; Waintal, X. What Limits the Simulation of Quantum Computers? Phys. Rev. X 2020, 10, 041038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aumasson, J.P. The impact of quantum computing on cryptography. CFSJ 2017, 2017, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, D.; Álvarez, G.A. Colloquium: Protecting quantum information against environmental noise. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 041001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, J.P.; Zurek, W.H. Environment-Induced Decoherence and the Transition from Quantum to Classical. In Fundamentals of Quantum Information: Quantum Computation, Communication, Decoherence and All That; Heiss, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 77–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Behrman, E.C.; Steck, J.E. Quantum learning with noise and decoherence: A robust quantum neural network. Quantum Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Huang, R.S.; Wallraff, A.; Girvin, S.M.; Schoelkopf, R.J. Cavity quantum electrodynamics for superconducting electrical circuits: An architecture for quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 69, 062320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, A.; Gambetta, J.; Wallraff, A.; Schuster, D.I.; Girvin, S.M.; Devoret, M.H.; Schoelkopf, R.J. Quantum-information processing with circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 032329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, D.I.; Houck, A.A.; Schreier, J.A.; Wallraff, A.; Gambetta, J.M.; Blais, A.; Frunzio, L.; Majer, J.; Johnson, B.; Devoret, M.H.; et al. Resolving photon number states in a superconducting circuit. Nature 2007, 445, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W.; Sahasrabudhe, H.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, H.C.; Veldhorst, M.; Hwang, J.C.C.; Mohiyaddin, F.A.; Hudson, F.E.; Itoh, K.M.; et al. Exchange Coupling in a Linear Chain of Three Quantum-Dot Spin Qubits in Silicon. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 1517–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhorst, M.; Hwang, J.C.C.; Yang, C.H.; Leenstra, A.W.; de Ronde, B.; Dehollain, J.P.; Muhonen, J.T.; Hudson, F.E.; Itoh, K.M.; Morello, A.; et al. An addressable quantum dot qubit with fault-tolerant control-fidelity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Yang, C.H.; Chan, K.W.; Tanttu, T.; Hensen, B.; Leon, R.C.C.; Fogarty, M.A.; Hwang, J.C.C.; Hudson, F.E.; Itoh, K.M.; et al. Fidelity benchmarks for two-qubit gates in silicon. Nature 2019, 569, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throckmorton, R.E.; Das Sarma, S. Crosstalk- and charge-noise-induced multiqubit decoherence in exchange-coupled quantum dot spin qubit arrays. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 245413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Wu, J.; Wang, X. Decoherence in exchange-coupled quantum spin-qubit systems: Impact of multiqubit interactions and geometric connectivity. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 109, 052628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, R.; Kavitha, T.; Panigrahi, D.; Bhalgat, A. An Õ(mn) Gomory-Hu tree construction algorithm for unweighted graphs. In Proceedings of the STOC ’07: Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, San Diego, CA, USA, 11–13 June 2007; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, R. On the All-Pairs-Shortest-Path Problem in Unweighted Undirected Graphs. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 1995, 51, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, T.D.; Jelezko, F.; Laflamme, R.; Nakamura, Y.; Monroe, C.; O’Brien, J.L. Quantum computers. Nature 2010, 464, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Pagano, G.; Hess, P.W.; Kyprianidis, A.; Becker, P.; Kaplan, H.; Gorshkov, A.V.; Gong, Z.X.; Monroe, C. Observation of a many-body dynamical phase transition with a 53-qubit quantum simulator. Nature 2017, 551, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, I. Quantum coherence and entanglement with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Nature 2008, 453, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, P.I.; Saenz, A. Quantum computation with ultracold atoms in a driven optical lattice. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 85, 050304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, H.; Keesling, A.; Semeghini, G.; Omran, A.; Wang, T.T.; Ebadi, S.; Bernien, H.; Greiner, M.; Vuletić, V.; Pichler, H.; et al. Parallel Implementation of High-Fidelity Multiqubit Gates with Neutral Atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 170503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, C.; Kim, J. Scaling the Ion Trap Quantum Processor. Science 2013, 339, 1164–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, D.; Gorman, S.K.; He, Y.; Kranz, L.; Simmons, M.Y. Impact of charge noise on electron exchange interactions in semiconductors. npj Quantum Inf. 2022, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephson, B. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Phys. Lett. 1962, 1, 251–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josephson, B.D. The discovery of tunnelling supercurrents. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1974, 46, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.Q.; Nori, F. Atomic physics and quantum optics using superconducting circuits. Nature 2011, 474, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, J.; Yu, T.M.; Gambetta, J.; Houck, A.A.; Schuster, D.I.; Majer, J.; Blais, A.; Devoret, M.H.; Girvin, S.M.; Schoelkopf, R.J. Charge-insensitive qubit design derived from the Cooper pair box. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 76, 042319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, H.; Schuster, D.I.; Bishop, L.S.; Kirchmair, G.; Catelani, G.; Sears, A.P.; Johnson, B.R.; Reagor, M.J.; Frunzio, L.; Glazman, L.I.; et al. Observation of High Coherence in Josephson Junction Qubits Measured in a Three-Dimensional Circuit QED Architecture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 240501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihara, F.; Fuse, T.; Ashhab, S.; Kakuyanagi, K.; Saito, S.; Semba, K. Superconducting qubit–oscillator circuit beyond the ultrastrong-coupling regime. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollár, A.J.; Fitzpatrick, M.; Houck, A.A. Hyperbolic lattices in circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 2019, 571, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.; Cummings, F. Comparison of quantum and semiclassical radiation theories with application to the beam maser. Proc. IEEE 1963, 51, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, F.W. Reminiscing about thesis work with E T Jaynes at Stanford in the 1950s. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2013, 46, 220202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.H.; Chan, K.W.; Harper, R.; Huang, W.; Evans, T.; Hwang, J.C.C.; Hensen, B.; Laucht, A.; Tanttu, T.; Hudson, F.E.; et al. Silicon qubit fidelities approaching incoherent noise limits via pulse engineering. Nat. Electron. 2019, 2, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W.; Saraiva, A.; Lim, W.H.; Yang, C.H.; Laucht, A.; Bertrand, B.; Rambal, N.; Hutin, L.; Escott, C.C.; Vinet, M.; et al. Single-Electron Operation of a Silicon-CMOS Quantum Dot Array with Integrated Charge Sensing. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 7882–7888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajac, D.M.; Sigillito, A.J.; Russ, M.; Borjans, F.; Taylor, J.M.; Burkard, G.; Petta, J.R. Resonantly driven CNOT gate for electron spins. Science 2018, 359, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.F.; Philips, S.G.J.; Kawakami, E.; Ward, D.R.; Scarlino, P.; Veldhorst, M.; Savage, D.E.; Lagally, M.G.; Friesen, M.; Coppersmith, S.N.; et al. A programmable two-qubit quantum processor in silicon. Nature 2018, 555, 633–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Watson, T.F.; Helsen, J.; Ward, D.R.; Savage, D.E.; Lagally, M.G.; Coppersmith, S.N.; Eriksson, M.A.; Wehner, S.; Vandersypen, L.M.K. Benchmarking Gate Fidelities in a Si/SiGe Two-Qubit Device. Phys. Rev. X 2019, 9, 021011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.R.; Guinn, C.R.; Gullans, M.J.; Sigillito, A.J.; Feldman, M.M.; Nielsen, E.; Petta, J.R. Two-qubit silicon quantum processor with operation fidelity exceeding 99%. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noiri, A.; Takeda, K.; Nakajima, T.; Kobayashi, T.; Sammak, A.; Scappucci, G.; Tarucha, S. Fast universal quantum gate above the fault-tolerance threshold in silicon. Nature 2022, 601, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Russ, M.; Samkharadze, N.; Undseth, B.; Sammak, A.; Scappucci, G.; Vandersypen, L.M.K. Quantum logic with spin qubits crossing the surface code threshold. Nature 2022, 601, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnik, P.; Arrasmith, A.; Coles, P.J.; Cincio, L. Error mitigation with Clifford quantum-circuit data. Quantum 2021, 5, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strikis, A.; Qin, D.; Chen, Y.; Benjamin, S.C.; Li, Y. Learning-Based Quantum Error Mitigation. PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 040330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincio, L.; Rudinger, K.; Sarovar, M.; Coles, P.J. Machine Learning of Noise-Resilient Quantum Circuits. PRX Quantum 2021, 2, 010324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlokapa, A.; Gheorghiu, A. A deep learning model for noise prediction on near-term quantum devices. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.10811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.A. Machine learning in physics: A short guide. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.10368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, P.M.K.; Mohan, A.; Srinivasa, K.G. Basics of Graph Theory. In Practical Social Network Analysis with Python; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, E. Graph and Network Theory in Physics. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1302.4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, A.; Severini, S.; Winter, A. Graph-Theoretic Approach to Quantum Correlations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 112, 040401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archdeacon, D.; Huneke, P. A Kuratowski theorem for nonorientable surfaces. J. Comb. Theory B 1989, 46, 173–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.C.; Wang, X. Noise filtering of composite pulses for singlet-triplet qubits. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.P. Machine Learning—A Probabilistic Perspective; Adaptive computation and machine learning series; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.P. Probabilistic Machine Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, J. Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville: Deep learning. Genet. Program. Evol. Mach 2018, 19, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudjianto, A.; Knauth, W.; Singh, R.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, A. Unwrapping The Black Box of Deep ReLU Networks: Interpretability, Diagnostics, and Simplification. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.04041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchi, J.; Hazan, E.; Singer, Y. Adaptive Subgradient Methods for Online Learning and Stochastic Optimization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2121–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Ruder, S. An overview of gradient descent optimization algorithms. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.04747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.C.; Roelofs, R.; Stern, M.; Srebro, N.; Recht, B. The marginal value of adaptive gradient methods in machine learning. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 4–9 December 2017; NIPS’17. pp. 4151–4161. [Google Scholar]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Müller, A.; Nothman, J.; Louppe, G.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1201.0490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J.C.F.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: A tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, X.; Zan, H.; Wang, Z.; Shi, J.; Zhang, S. Privacy-Preserving Bidirectional Data Transmission of Smart Grid Via Semi-Quantum Computation: On Mutual Identity and Message Authentication. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 22, 5537–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature Category | Specific Features | Mathematical Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Structural | Number of nodes (n), edges (m), density () | , , density |

| Distance-Based | Diameter (D), average shortest path (L) | , |

| Algebraic | Algebraic connectivity () | Second smallest Laplacian eigenvalue: |

| Local Structural | Clustering coefficient (C) | , for |

| Special Properties | Eulerian, planarity | Eulerian: all even degrees; planar: no edge crossings |

| Degree Statistics | Mean (), std (), skewness () | Moments of degree distribution: |

| Centrality | Betweenness centrality () | , |

| Spectral | Spectral entropy (S) | |

| Robustness | Noise sensitivity () |

| Histogram Gradient Boosting | Random Forest | |

|---|---|---|

| Superconducting | ||

| 0.9682 ± 0.0286 | 0.9651 ± 0.0187 | |

| MAE | 0.0126 ± 0.0001 | 0.0131 ± 0.0001 |

| Semiconductor | ||

| 0.9999 ± 0.0044 | 0.9999 ± 0.0026 | |

| MAE | 0.0087 ± 0.0002 | 0.0091 ± 0.0001 |

| Model | Training → Testing | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Histogram Gradient Boosting | Superconducting → Semiconductor | −0.39 ± 0.0099 |

| Histogram Gradient Boosting | Semiconductor → Superconducting | −433.60 ± 86.55 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fu, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Xiong, R. Machine Learning the Decoherence Property of Superconducting and Semiconductor Quantum Devices from Graph Connectivity. Entropy 2026, 28, 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010089

Fu Q, Liu J, Wang X, Xiong R. Machine Learning the Decoherence Property of Superconducting and Semiconductor Quantum Devices from Graph Connectivity. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):89. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010089

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Quan, Jie Liu, Xin Wang, and Rui Xiong. 2026. "Machine Learning the Decoherence Property of Superconducting and Semiconductor Quantum Devices from Graph Connectivity" Entropy 28, no. 1: 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010089

APA StyleFu, Q., Liu, J., Wang, X., & Xiong, R. (2026). Machine Learning the Decoherence Property of Superconducting and Semiconductor Quantum Devices from Graph Connectivity. Entropy, 28(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010089