Positive-Unlabeled Learning in Implicit Feedback from Data Missing-Not-At-Random Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose a two-phase debiasing framework that provides a PU learning paradigm with corresponding IPS and DR estimators to predict preference using implicit feedback.

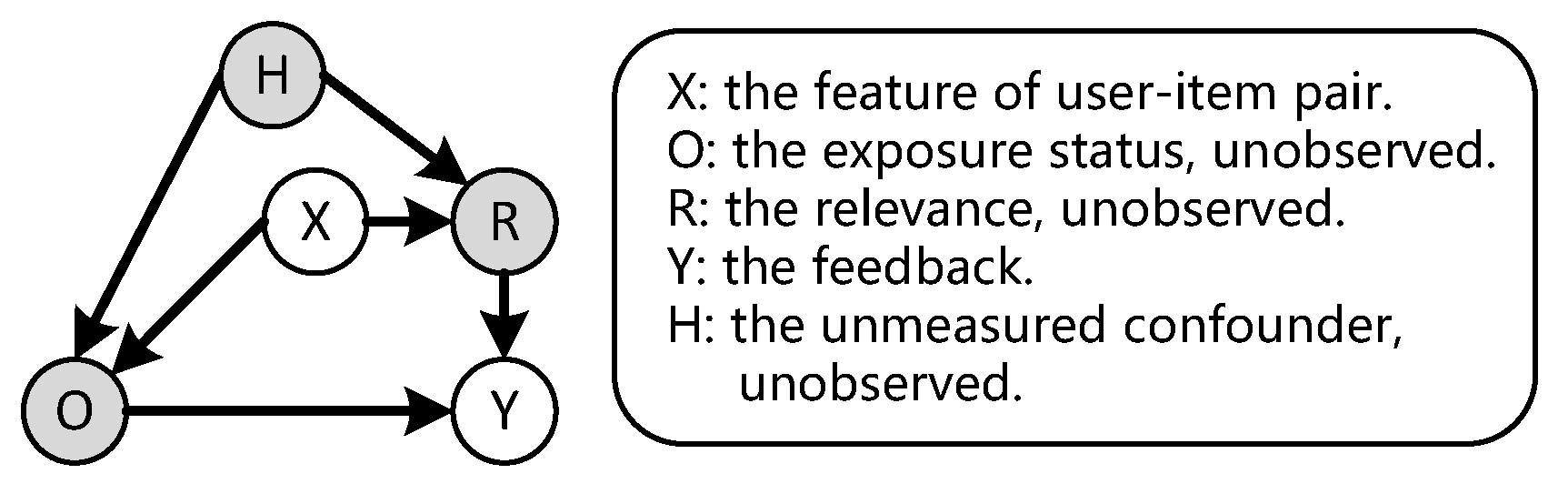

- We reveal the risk of unmeasured confounders for implicit feedback and propose a debiasing method to robustly mitigate the bias.

- We conduct extensive experiments to validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework and methods.

2. Related Works

3. Problem Setup

PU Learning for Recommendation System

4. Proposed Method

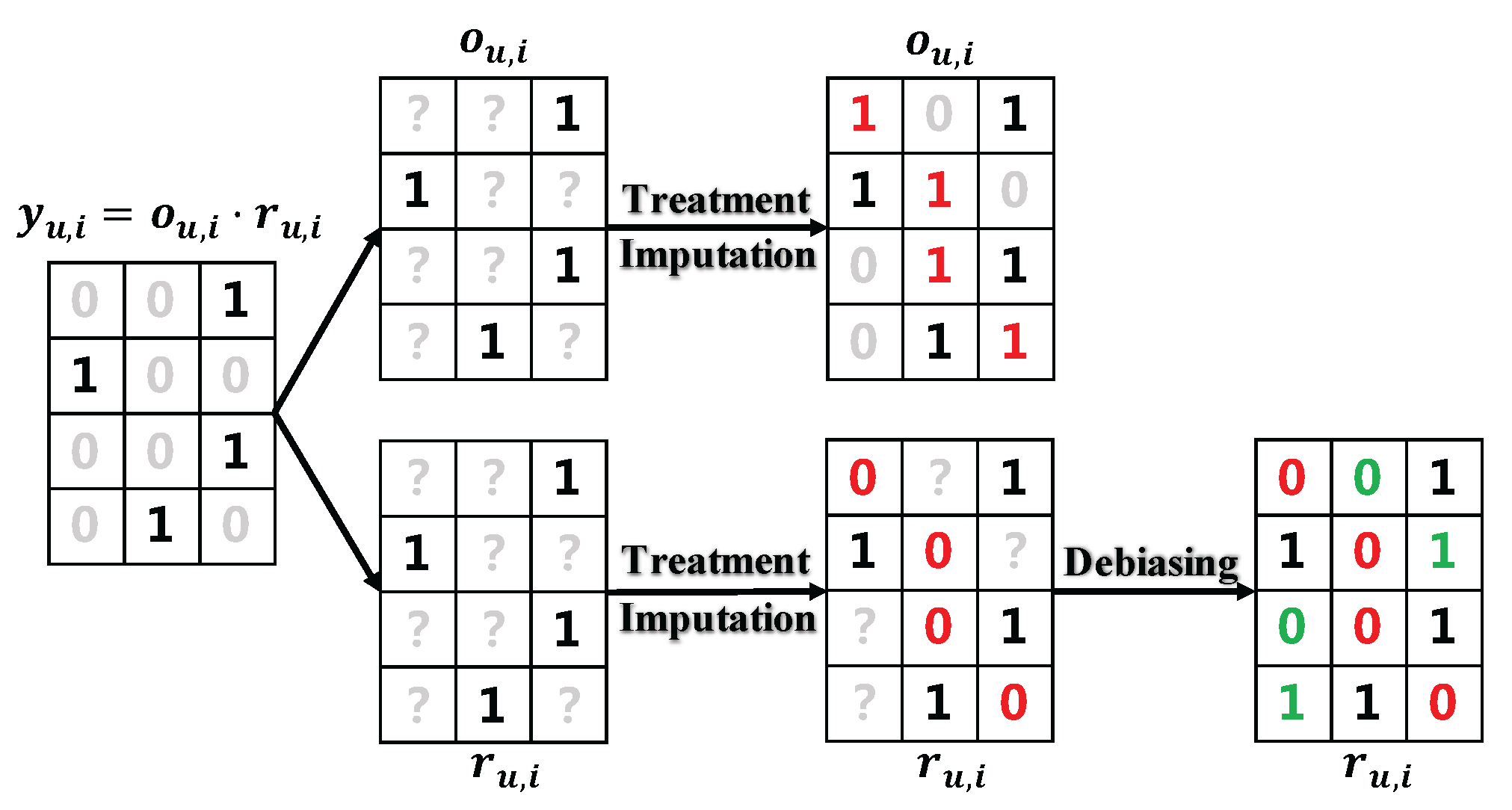

4.1. PU Learning for Implicit Feedback

4.2. Two-Phase Debiasing Framework

4.3. Treatment Imputation Phase

4.4. Debiasing Phase

4.4.1. In the Absence of Unmeasured Confounders

4.4.2. In the Presence of Unmeasured Confounders

5. Experiments

- RQ1.

- Does the proposed method outperform the existing debiasing methods on real-world datasets?

- RQ2.

- How does each of the stages affect the debiasing performance of the proposed method?

- RQ3.

- Does our method stably outperform for different SVDD sampling ratios on positive treatment imputations?

- RQ4.

- How does the adversarial strength affect the debiasing performance?

- RQ5.

- Given the model complexity, is there a potential overfitting issue?

5.1. Experimental Setup

- Datasets. Measuring the debiasing performance requires that the dataset contains both missing-not-at-random (MNAR) ratings and missing-at-random (MAR) ratings. There are three public datasets that meet the requirements. The first is Coat Shopping (https://www.cs.cornell.edu/~schnabts/mnar/, accessed on 3 November 2025), which contains 6960 MNAR ratings and 4640 MAR ratings in total. Both MNAR ratings and MAR ratings are generated by 290 users to 300 items. Each user rates their favorite 24 products to generate the former, while each user randomly rates 16 products to make up of the latter. The second is Yahoo! R3 (https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/limitiao/yahoor3, accessed on 3 November 2025), which contains ratings from 15,400 users to 1000 items. Each user rates several items to generate the 311,704 MNAR ratings, while the first 5400 users are asked to randomly rate 10 items, which make up the 54,000 MAR ratings. The third is KuaiRec (https://kuairec.com/, accessed on 3 November 2025), a public large-scale dataset, collected via a video-sharing platform, which consists of 4,676,570 video watching ratio records from 1411 users and 3327 videos. To further demonstrate the generalizability of our method performance, we utilize its unbiased data, where a subset of users is asked to rate sampled items uniformly at random, providing 13,454 MAR ratings, leaving 201,171 interactions to serve as MNAR data.

- Pre-processing. The difference between the rating prediction task in implicit and explicit feedback settings is that the implicit feedback cannot see the rating if the user does not like the item. Following previous studies [37,38,59], we binarize the ratings as negative if the rating is less than 3, otherwise as positive. Therefore, we remove the samples with ratings less than 3 from three datasets, leaving 3622 positive samples for the Coat dataset, 174,208 positive samples for the Yahoo! R3 dataset, and 105,186 positive samples for the KuaiRec dataset.

- Baselines. To validate the efficiency of the proposed debiasing framework, we compare our methods with the following baselines:

- Base model: Matrix Factorization (MF) [77] is used as the base model frequently in debiasing recommendations.

- WMF: WMF [15] is a classic method for implicit feedback. It up-weights the loss of all positive feedback to reflect greater confidence in the positive feedback than the negative feedback.

- BPR: BPR [42] is another classic method for implicit feedback. It assumes that unclicked items are less preferred than clicked items and, therefore, maximizes the posterior probability under this assumption.

- IPS [22]: IPS is a classic debiasing method that weights the loss function by the corresponding inverse propensity scores to reduce the bias.

- DR [59]: DR is another classic debiasing method that includes both the propensity and the imputation model and aims to minimize the DR loss to reduce bias.

- DR-JL [37]: DR-JL is based on the DR method. It applies a joint learning algorithm between the prediction and the imputation model.

- MRDR-JL [38]: MRDR-JL is a variation of DR-JL, which changes the original DR imputation loss to MRDR imputation loss.

- Negative Sampling for Baselines. Note that the existing methods require training with both positive samples and negative samples. However, we can only observe positive samples in the implicit feedback setting. Thus, we use the negative sampling method with the baseline methods. Specifically, we randomly select user–item pairs in the missing data and mark them as negative samples, and the estimated propensities are obtained by logistic regression.

- Experimental protocols and details. Following the previous studies [22,60], MSE, AUC, NDCG@5 and NDCG@10 are used as our evaluation metrics. All experiments are implemented on PyTorch v2.6.0 with Adam as the optimizer (for all experiments, we use GeForce RTX 2060 as the computing resource). To mitigate overfitting, we employ L2 regularization via weight decay and early stopping during training, which is terminated when the relative loss decrease falls below a tolerance threshold for 5 consecutive epochs. We tune the weight decay in and the learning rate in . In addition, we tune the sample ratio between the imputed negative and positive samples in in RQ3 and set it to 1.0 for other RQs. For the RD-based methods, we tune the adversarial strength gamma in in RQ4 and set it to 1.1 for other RQs. We set the batch size to 128 for Coat, 2048 for Yahoo! R3 and KuaiRec, and use the default parameter values in the SVDD function in scikit-learn v1.3.0 package for the SVDD-based methods on both datasets.

5.2. Real-World Performance (RQ1)

5.3. Ablation Study (RQ2)

5.4. In-Depth Analysis (RQ3 and RQ4)

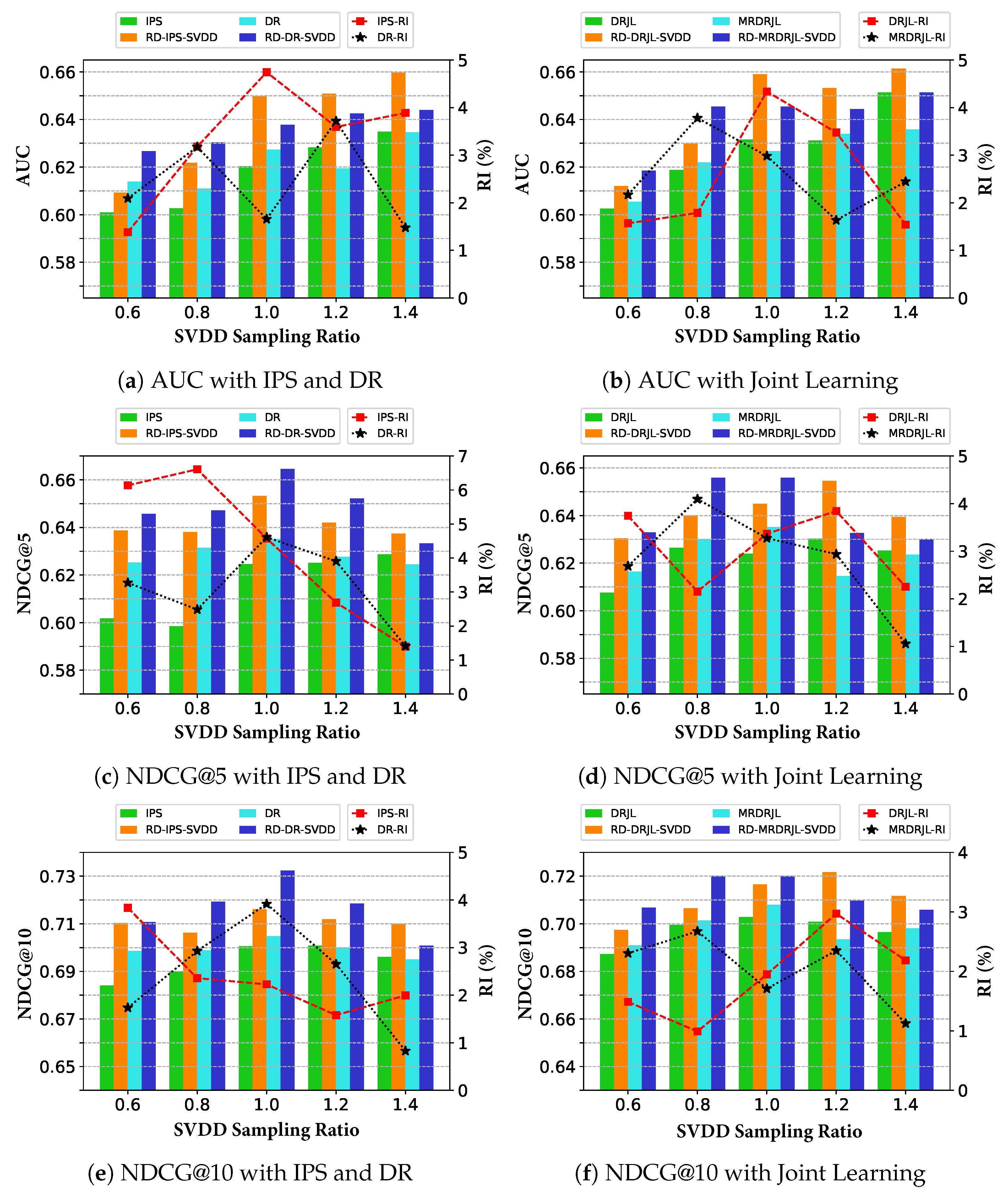

- Effect of SVDD Sampling Ratio in the First Stage. In the first stage, SVDD can provide more reliable imputations for positive treatment, leading to more accurate estimation of propensities and relevance predictions. Figure 3 demonstrates the effect of the various debiasing methods on AUC, NDCG@5, and NDCG@10 at different sample ratios of positive treatment imputations. Remarkably, the proposed method outperforms significantly over the baseline with all SVDD sampling ratios. In addition, predictive performance reaches an optimal for proper positive sampling ratios between 0.8 and 1.2. This is explained by the fact that too many or too few imputations of positive treatment can cause data imbalance, and the positive imputations by the SVDD method result in lower confidence as the number of imputations increases.

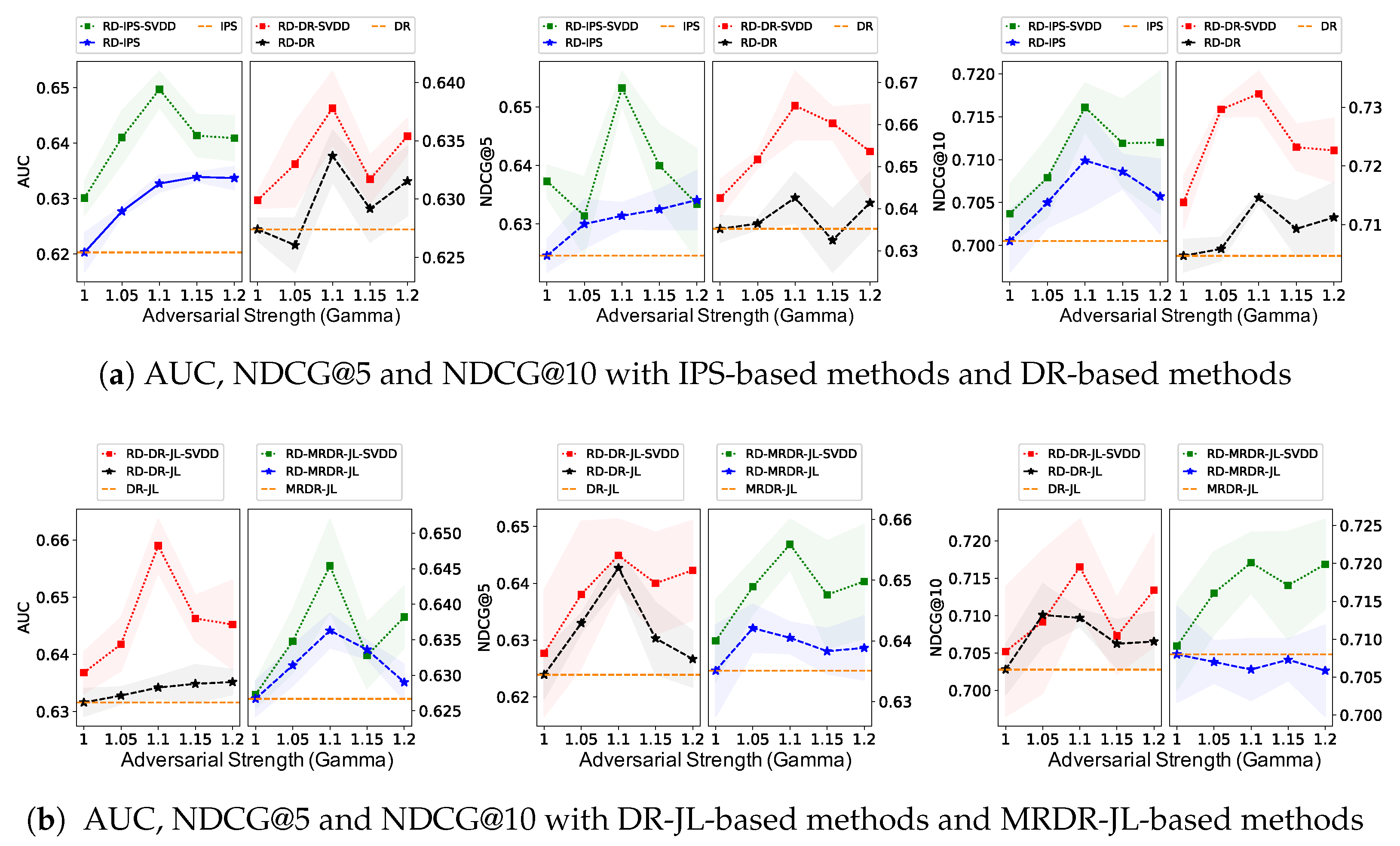

- Sensitivity of Adversarial Strength in the Second Stage. For the second stage, we conducted repeated experiments to investigate the effect of different adversarial strengths of RD on the AUC, NDCG@5, and NDCG@10 of the various debiasing methods, and the results are shown in Figure 4, where the yellow dashed line shows the performance of the baseline method without RD. The proposed method stably outperforms the baselines for almost all adversarial strengths, validating the effectiveness of RD’s tuning for unmeasured confounders. In addition, a higher adversarial strength increases the variance, and a suitable adversarial strength between 1.05 and 1.15 leads to optimal performance. Such empirical results are compatible with the theoretical guarantee, where a larger adversarial strength not only has a stronger effect on the adjustment of unmeasured confounders but also increases the hypothesis space of the prediction model, leading to a higher variance as well as worsening the performance of the model given by the minimax method. When the adversarial strength is set to 1, it is equivalent to not adjusting for unmeasured confounders, which degenerates to debiasing methods without using RD techniques.

5.5. Overfitting Analysis (RQ5)

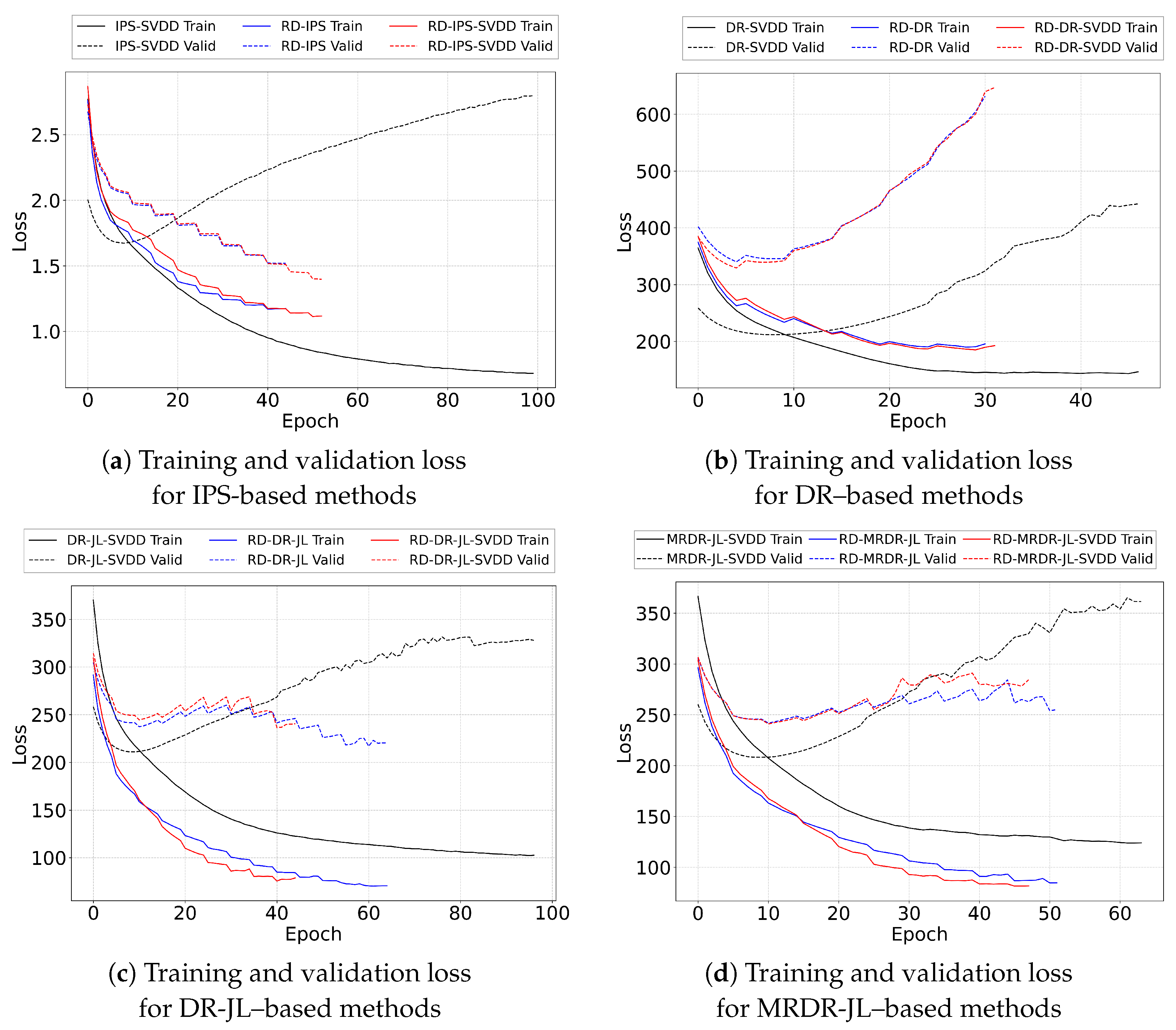

- Overfitting Analysis. We evaluate whether the proposed two-phase debiasing framework leads to overfitting by tracking the IPS-weighted training and validation losses across epochs. The trajectories in Figure 5 show that SVDD-only variants within the IPS, DR-JL, and MRDR-JL families converge slowly and display clear upward trends in validation loss, reflecting that treatment imputation alone increases data coverage but does not correct the confounding structure of the logged data, making the models sensitive to pseudo-negative noise. Adding the RD phase mitigates this issue: RD-only variants converge more quickly and exhibit noticeably reduced overfitting, which is consistent with RD’s ability to regulate propensity adjustments and limit the influence of unmeasured confounders. The full two-phase method combining SVDD and RD further stabilizes the trajectories, reaching convergence more rapidly and maintaining lower validation losses near convergence.

- Runtime Analysis. In addition, we investigate the potential computational overhead issue and conduct a comprehensive runtime analysis across all three datasets. The total training time for each debiasing method is summarized in Table 2. A key observation is that our complete two-phase methods, such as RD-IPS-SVDD, RD-DR-SVDD, exhibit training times comparable to their base single-phase or non-robust counterparts, attributed to the stabilized training dynamics and early stopping. The results demonstrate that the superior prediction performance reported in Table 1 is achieved with a measurable yet manageable computational overhead.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Proofs

Appendix B. Exploratory Experiment

| Method | MSE | AUC | NDCG@5 | NDCG@10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + MRDR-JL | 0.2312 | 0.6324 | 0.6397 | 0.7078 |

| + MRDR-JL-SVDD | 0.2309 | 0.6403 | 0.6432 | 0.7117 |

| + RD_MRDR-JL | 0.2313 | 0.6434 | 0.6577 | 0.7139 |

| + RD_MRDR-JL-SVDD | 0.2215 | 0.6521 | 0.6626 | 0.7252 |

References

- Denis, F.; Gilleron, R.; Letouzey, F. Learning from positive and unlabeled examples. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2005, 348, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, M.; Niu, G.; Sugiyama, M. Convex formulation for learning from positive and unlabeled data. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning, Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 1386–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Kiryo, R.; Niu, G.; du Plessis, M.C.; Sugiyama, M. Positive-unlabeled learning with non-negative risk estimator. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 1674–1684. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, M.; Teshima, T.; Honda, J. Learning from positive and unlabeled data with a selection bias. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, J.; Davis, J. Learning from positive and unlabeled data: A survey. Mach. Learn. 2020, 109, 719–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Chen, W.; Xu, M. Positive-unlabeled learning from imbalanced data. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-21), Virtual, 19–26 August 2021; pp. 2995–3001. [Google Scholar]

- Chapel, L.; Alaya, M.Z.; Gasso, G. Partial optimal transport with applications on positive-unlabeled learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 2903–2913. [Google Scholar]

- Vinay, M.; Yuan, S.; Wu, X. Fraud detection via contrastive positive unlabeled learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Osaka, Japan, 17–20 December 2022; pp. 1475–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, S.; Loomba, J.; Sharma, S.; Chapman, S.A.; Brown, D.E. Determining risk factors for long COVID using positive unlabeled learning on electronic health records data from NIH N3C. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Jacksonville, FL, USA, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 430–436. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Feng, F.; He, X.; Nie, L.; Chua, T.S. Denoising implicit feedback for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Virtual, 8–12 March 2021; pp. 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Jannach, D.; Lerche, L.; Zanker, M. Recommending based on implicit feedback. In Social Information Access; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 510–569. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Sui, H. Addressing Correlated Latent Exogenous Variables in Debiased Recommender Systems. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining V. 2, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–7 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Dai, X.; Shan, R.; Chen, B.; Tang, R.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, W. Large language models make sample-efficient recommender systems. Front. Comput. Sci. 2025, 19, 194328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, Y.; Yaginuma, S.; Nishino, Y.; Sakata, H.; Nakata, K. Unbiased recommender learning from missing-not-at-random implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Houston, TX, USA, 3–7 February 2020; pp. 501–509. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Koren, Y.; Volinsky, C. Collaborative filtering for implicit feedback datasets. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Pisa, Italy, 15–19 December 2008; pp. 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, D.; Liu, X.; Li, H. Entire space counterfactual learning for reliable content recommendations. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Zheng, C.; Wang, W.; Jiang, J.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Feng, F. Batch-Adaptive Doubly Robust Learning for Debiasing Post-Click Conversion Rate Prediction Under Sparse Data. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, S.; Lee, J.; Lee, J. Bilateral Self-unbiased Learning from Biased Implicit Feedback. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Madrid, Spain, 11–15 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Li, H.; Yao, L.; Gong, M. Counterfactual implicit feedback modeling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 November–7 December 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, D.; Chen, J.; Zheng, K.; Chen, E.; Zhou, X. Ranking-based Implicit Regularization for One-Class Collaborative Filtering. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 34, 5951–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T.J.; Shpitser, I. On the definition of a confounder. Ann. Stat. 2013, 41, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, T.; Swaminathan, A.; Singh, A.; Chandak, N.; Joachims, T. Recommendations as treatments: Debiasing learning and evaluation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, New York, NY, USA, 19–24 June 2016; pp. 1670–1679. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Li, H.; Deng, Y.; Hu, W.; Dai, Q.; Dong, Z.; Sun, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, X.H. On the opportunity of causal learning in recommendation systems: Foundation, estimation, prediction and challenges. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.06716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Li, H.; Wu, P.; Dong, Z.; Zhou, X.H.; Zhang, R.; He, X.; Zhang, R.; Sun, J. A Generalized Doubly Robust Learning Framework for Debiasing Post-Click Conversion Rate Prediction. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, I.; He, X.; Kanagal, B.; Rendle, S. A Generic Coordinate Descent Framework for Learning from Implicit Feedback. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 1341–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lian, D.; Zheng, K. Improving one-class collaborative filtering via ranking-based implicit regularizer. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Sun, Y.; Shi, Y.; Hong, L. On Sampling Strategies for Neural Network-based Collaborative Filtering. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–17 August 2017; pp. 767–776. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Liao, L.; Zhang, H.; Nie, L.; Hu, X.; Chua, T.S. Neural collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web, Perth, Australia, 3–7 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, D.; Liu, Q.; Chen, E. Personalized Ranking with Importance Sampling. In Proceedings of the Web Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 April 2020; pp. 1093–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Tan, Y.; Pan, L.; Liu, T.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Lin, Z. Unbiased recommender learning from implicit feedback via weakly supervised learning. In Proceedings of the Forty-Second International Conference on Machine Learning, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Y. Unbiased Pairwise Learning from Biased Implicit Feedback. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGIR on International Conference on Theory of Information Retrieval, Virtual, 14–17 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Caverlee, J. Unbiased Implicit Recommendation and Propensity Estimation via Combinational Joint Learning. In Proceedings of the 14th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Virtual, 22–26 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Woong Lee, J.; Park, S.; Lee, J. Dual Unbiased Recommender Learning for Implicit Feedback. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 11–15 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo, G.; Penz, D.; Schedl, M. Debiasing Implicit Feedback Recommenders via Sliced Wasserstein Distance-based Regularization. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Prague, Czech Republic, 22–26 September 2025; pp. 1153–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Bekker, J.; Robberechts, P.; Davis, J. Beyond the selected completely at random assumption for learning from positive and unlabeled data. In Proceedings of the Oint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Würzburg, Germany, 16–20 September 2019; pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- De Block, S.; Bekker, J. Bagging propensity weighting: A robust method for biased PU learning. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Workshop on Learning with Imbalanced Domains: Theory and Applications 2022, Grenoble, France, 23 September 2022; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Y.; Qi, J. Doubly robust joint learning for recommendation on data missing not at random. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–15 June 2019; pp. 6638–6647. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Zou, L.; Liu, Y.; Ye, W.; Cheng, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Yin, D.; Chang, Y. Enhanced doubly robust learning for debiasing post-click conversion rate estimation. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 11–15 July 2021; pp. 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wu, P.; Cui, P. Propensity matters: Measuring and enhancing balancing for recommendation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 20182–20194. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zheng, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; Feng, F.; Zhou, X.H. Debiased recommendation with noisy feedback. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Xia, T. CBPL: A unified calibration and balancing propensity learning framework in causal recommendation for debiasing. In Proceedings of the IJCAI 2025 Workshop Causal Learning RecSys, Montreal, QC, Canada, 16–22 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rendle, S.; Freudenthaler, C.; Gantner, Z.; Schmidt-Thieme, L. BPR: Bayesian Personalized Ranking from Implicit Feedback. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 18–21 June 2009; pp. 452–461. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Wang, S.; Shu, K.; Li, J.; Chen, B.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y. Personalized privacy-preserving social recommendation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Feng, F.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Chua, T.S. Deconfounded recommendation for alleviating bias amplification. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 1717–1725. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wu, K.; Zheng, C.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Geng, Z.; Feng, F.; He, X.; Wu, P. Removing hidden confounding in recommendation: A unified multi-task learning approach. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 54614–54626. [Google Scholar]

- Tax, D.M.; Duin, R.P. Support vector data description. Mach. Learn. 2004, 54, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Dong, H.; Wang, X.; Feng, F.; Wang, M.; He, X. Bias and debias in recommender system: A survey and future directions. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2023, 41, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wen, R.; Huang, S.L.; Kuruoglu, E.; Zheng, Y. Information theoretic counterfactual learning from missing-not-at-random feedback. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 1854–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, F.; He, X.; Wei, T.; Song, C.; Ling, G.; Zhang, Y. Causal intervention for leveraging popularity bias in recommendation. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, 11–15 July 2021; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zheng, C.; Ding, S.; Feng, F.; He, X.; Geng, Z.; Wu, P. Be aware of the neighborhood effect: Modeling selection bias under interference for recommendation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.19620. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Adaptive structure learning with partial parameter sharing for post-click conversion rate prediction. In Proceedings of the 48th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Padua, Italy, 13–18 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, Q.; Bi, K.; Luo, C.; Guo, J.; Croft, W.B. Unbiased learning to rank with unbiased propensity estimation. In Proceedings of the 41st International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research & Development in Information Retrieval, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 8–12 July 2018; pp. 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, X.; Yu, Y. Are you influenced by others when rating? Improve rating prediction by conformity modeling. In Proceedings of the 10th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Boston, MA, USA, 15–19 September 2016; pp. 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zheng, C.; Wang, S.; Wu, K.; Wang, E.; Wu, P.; Geng, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.H. Relaxing the accurate imputation assumption in doubly robust learning for debiased collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the Forty-First International Conference on Machine Learning, Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Zheng, C.; Zhou, X.H.; Wu, P. Stabilized Doubly Robust Learning for Recommendation on Data Missing Not at Random. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.04701v2. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Lyu, Y.; Zheng, C.; Wu, P. TDR-CL: Targeted doubly robust collaborative learning for debiased Recommendations. In Proceedings of the ICLR, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Wu, P.; Feng, F.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Addressing Unmeasured Confounder for Recommendation with Sensitivity Analysis. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Charlin, L.; McInerney, J.; Blei, D.M. Modeling user exposure in recommendation. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–15 April 2016; pp. 951–961. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, Y. Doubly robust estimator for ranking metrics with post-click conversions. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Virtual, 22–26 September 2020; pp. 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Cui, Y.; Xuan, Y.; Wang, C.; Belongie, S.; Estrin, D. Unbiased offline recommender evaluation for missing-not-at-random implicit feedback. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–7 October 2018; pp. 279–287. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Tan, Y.; Pan, L.; Liu, T.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Lin, Z. Unbiased recommender learning from implicit feedback via progressive proximal transport. In Proceedings of the Forty-Second International Conference on Machine Learning, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 13–19 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Plessis, M.C.d.; Niu, G.; Sugiyama, M. Analysis of learning from positive and unlabeled data. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014, 27, 703–711. [Google Scholar]

- Northcutt, C.G.; Wu, T.; Chuang, I.L. Learning with confident examples: Rank pruning for robust classification with noisy labels. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.01936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Chaib-Draa, B.; Li, C.; Zhao, Q. Generative adversarial positive-unlabeled learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.08054. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, C.; Shi, H.; Liu, T.; Zhang, C.; Yang, J.; Tao, D. Loss decomposition and centroid estimation for positive and unlabeled learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 43, 918–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zhao, P.; Chen, C.; Qiao, B.; Du, C.; Zhang, H.; Wu, W.; Cai, S.; He, B.; Rajmohan, S.; et al. Pulns: Positive-unlabeled learning with effective negative sample selector. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 11–15 October 2021; Volume 35, pp. 8784–8792. [Google Scholar]

- Schölkopf, B.; Platt, J.C.; Shawe-Taylor, J.; Smola, A.J.; Williamson, R.C. Estimating the support of a high-dimensional distribution. Neural Comput. 1999, 11, 1443–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzen, E. On estimation of a probability density function and mode. Ann. Math. Stat. 1962, 33, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gewers, F.L.; Ferreira, G.R.; Arruda, H.F.D.; Silva, F.N.; Comin, C.H.; Amancio, D.R.; Costa, L.d.F. Principal component analysis: A natural approach to data exploration. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, P.; Larochelle, H.; Bengio, Y.; Manzagol, P.A. Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Machine Learning, Helsinki, Finland, 5–9 July 2008; pp. 1096–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.H. Isolation forest. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Pisa, Italy, 15–19 December 2008; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Bao, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, K.; Lin, Q.; Wen, H.; Ramezani, R. Large-scale Causal Approaches to Debiasing Post-click Conversion Rate Estimation with Multi-task Learning. In Proceedings of the Web Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–24 April 2020; pp. 2775–2781. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Liu, B. Learning from positive and unlabeled examples with different data distributions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Machine Learning, Porto, Portugal, 3–7 October 2005; pp. 218–229. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, D.; Charlin, L.; Blei, D.M. The deconfounded recommender: A causal inference approach to recommendation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.06581. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, P.R.; Rosenbaum, P.; Briskman. Design of Observational Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Koren, Y.; Bell, R.; Volinsky, C. Matrix factorization techniques for recommender systems. Computer 2009, 42, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Krishnan, R.G.; Hoffman, M.D.; Jebara, T. Variational autoencoders for collaborative filtering. In Proceedings of the 2018 World Wide Web Conference, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Method | Coat | Yahoo!R3 | KuaiRec | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metrics | MSE | AUC | N@5 | N@10 | MSE | AUC | N@5 | N@10 | MSE | AUC | N@5 | N@10 |

| Base Model (MF) | 0.2414 | 0.6038 | 0.6294 | 0.6998 | 0.2089 | 0.6329 | 0.7104 | 0.8062 | 0.1837 | 0.8095 | 0.5315 | 0.5498 |

| + WMF | 0.2447 | 0.6289 | 0.6356 | 0.7060 | 0.2105 | 0.6487 | 0.7279 | 0.8174 | 0.1818 | 0.8180 | 0.5348 | 0.5544 |

| + BPR-MF | 0.2492 | 0.6136 | 0.6378 | 0.7061 | 0.2057 | 0.6433 | 0.7102 | 0.8074 | 0.1848 | 0.8178 | 0.5342 | 0.5447 |

| + Rel-MF | 0.2404 | 0.6312 | 0.6368 | 0.7025 | 0.2128 | 0.6655 | 0.7138 | 0.8069 | 0.1786 | 0.8204 | 0.5357 | 0.5486 |

| + IPS | 0.2350 | 0.6203 | 0.6246 | 0.7005 | 0.2034 | 0.6328 | 0.7053 | 0.8050 | 0.1752 | 0.8133 | 0.5130 | 0.5374 |

| + IPS-SVDD | 0.2339 | 0.6301 | 0.6373 | 0.7037 | 0.2116 | 0.6641 | 0.7267 | 0.8152 | 0.1733 | 0.8205 | 0.5269 | 0.5472 |

| + RD-IPS | 0.2328 | 0.6327 | 0.6314 | 0.7099 | 0.2097 | 0.6658 | 0.7215 | 0.8125 | 0.1728 | 0.8193 | 0.5295 | 0.5521 |

| + RD-IPS-SVDD | 0.2280 | 0.6497 | 0.6532 | 0.7161 | 0.1934 | 0.6663 | 0.7297 | 0.8184 | 0.1691 | 0.8265 | 0.5401 | 0.5603 |

| + DR | 0.2473 | 0.6274 | 0.6352 | 0.7047 | 0.2049 | 0.6379 | 0.7161 | 0.8110 | 0.1775 | 0.8305 | 0.5337 | 0.5541 |

| + DR-SVDD | 0.2405 | 0.6299 | 0.6425 | 0.7138 | 0.2054 | 0.6565 | 0.7252 | 0.8166 | 0.1757 | 0.8287 | 0.5357 | 0.5533 |

| + RD-DR | 0.2438 | 0.6337 | 0.6426 | 0.7146 | 0.2057 | 0.6675 | 0.7227 | 0.8144 | 0.1787 | 0.8315 | 0.5371 | 0.5530 |

| + RD-DR-SVDD | 0.2410 | 0.6378 | 0.6645 | 0.7323 | 0.1998 | 0.6706 | 0.7358 | 0.8224 | 0.1777 | 0.8324 | 0.5458 | 0.5544 |

| + DR-JL | 0.2339 | 0.6316 | 0.6239 | 0.7028 | 0.2024 | 0.6329 | 0.7066 | 0.8050 | 0.1761 | 0.8182 | 0.5206 | 0.5369 |

| + DR-JL-SVDD | 0.2326 | 0.6368 | 0.6277 | 0.7052 | 0.2036 | 0.6346 | 0.7166 | 0.8105 | 0.1736 | 0.8160 | 0.5232 | 0.5444 |

| + RD-DR-JL | 0.2324 | 0.6342 | 0.6427 | 0.7097 | 0.1976 | 0.6419 | 0.7098 | 0.8064 | 0.1761 | 0.8182 | 0.5223 | 0.5463 |

| + RD-DR-JL-SVDD | 0.2288 | 0.6590 | 0.6449 | 0.7165 | 0.1958 | 0.6477 | 0.7166 | 0.8122 | 0.1733 | 0.8197 | 0.5232 | 0.5464 |

| + MRDR-JL | 0.2367 | 0.6267 | 0.6351 | 0.7080 | 0.2037 | 0.6313 | 0.7077 | 0.8062 | 0.1770 | 0.8142 | 0.5238 | 0.5394 |

| + MRDR-JL-SVDD | 0.2350 | 0.6273 | 0.6400 | 0.7091 | 0.1992 | 0.6377 | 0.7165 | 0.8116 | 0.1759 | 0.8166 | 0.5302 | 0.5489 |

| + RD-MRDR-JL | 0.2333 | 0.6363 | 0.6405 | 0.7060 | 0.2013 | 0.6369 | 0.7197 | 0.8127 | 0.1757 | 0.8163 | 0.5257 | 0.5387 |

| + RD-MRDR-JL-SVDD | 0.2288 | 0.6454 | 0.6559 | 0.7201 | 0.1990 | 0.6466 | 0.7217 | 0.8144 | 0.1689 | 0.8190 | 0.5331 | 0.5557 |

| Method | Coat | Yahoo!R3 | KuaiRec |

|---|---|---|---|

| MF | 7.61 | 15.31 | 8.62 |

| MF-SVDD | 4.37 | 9.59 | 4.71 |

| IPS | 7.85 | 8.23 | 13.35 |

| IPS-SVDD | 6.28 | 11.44 | 11.42 |

| RD-IPS | 3.54 | 59.66 | 51.84 |

| RD-IPS-SVDD | 4.48 | 58.09 | 54.31 |

| DR | 4.28 | 50.89 | 29.26 |

| DR-SVDD | 4.81 | 57.08 | 26.30 |

| RD-DR | 4.32 | 104.22 | 29.24 |

| RD-DR-SVDD | 4.37 | 99.02 | 29.88 |

| DR-JL | 10.99 | 74.61 | 88.13 |

| DR-JL-SVDD | 20.58 | 68.04 | 69.75 |

| RD-DR-JL | 16.90 | 125.52 | 125.16 |

| RD-DR-JL-SVDD | 12.14 | 132.56 | 114.56 |

| MRDR-JL | 10.63 | 68.97 | 47.56 |

| MRDR-JL-SVDD | 13.89 | 79.24 | 78.00 |

| RD-MRDR-JL | 17.20 | 185.23 | 165.26 |

| RD-MRDR-JL-SVDD | 12.93 | 189.68 | 157.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Xia, T.; Yang, L. Positive-Unlabeled Learning in Implicit Feedback from Data Missing-Not-At-Random Perspective. Entropy 2026, 28, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010041

Wang S, Xia T, Yang L. Positive-Unlabeled Learning in Implicit Feedback from Data Missing-Not-At-Random Perspective. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Sichao, Tianyu Xia, and Lingxiao Yang. 2026. "Positive-Unlabeled Learning in Implicit Feedback from Data Missing-Not-At-Random Perspective" Entropy 28, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010041

APA StyleWang, S., Xia, T., & Yang, L. (2026). Positive-Unlabeled Learning in Implicit Feedback from Data Missing-Not-At-Random Perspective. Entropy, 28(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010041