Dynamic Synchronization and Resonance as the Origin of 1/f Fluctuations—Amplitude Modulation Across Music and Nature

Abstract

1. Introduction

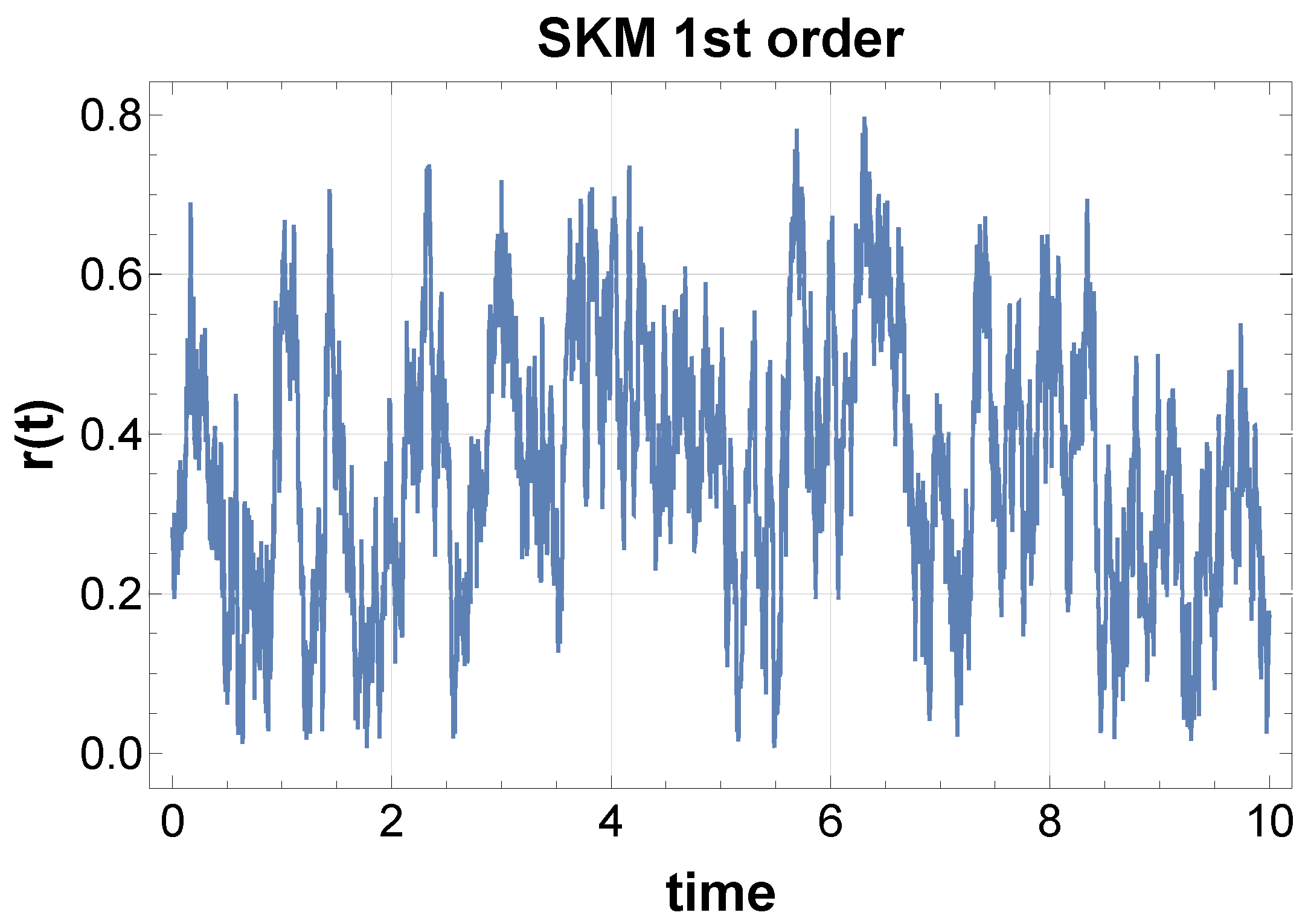

- Synchronization: Stochastic synchronization among interacting oscillators leads to recurrent cycles of phase alignment and dispersion. We model this process using an extended stochastic Kuramoto framework that produces persistent low-frequency envelope variations without requiring fine-tuning of the classical synchronization threshold.

- Resonance: Resonance-driven spectral shaping, in which environmental or structural eigenmodes selectively amplify certain frequencies, creates envelope modulations even in the absence of direct coupling among oscillators.

2. A Simple Origin of 1/f Fluctuations—Amplitude Modulation

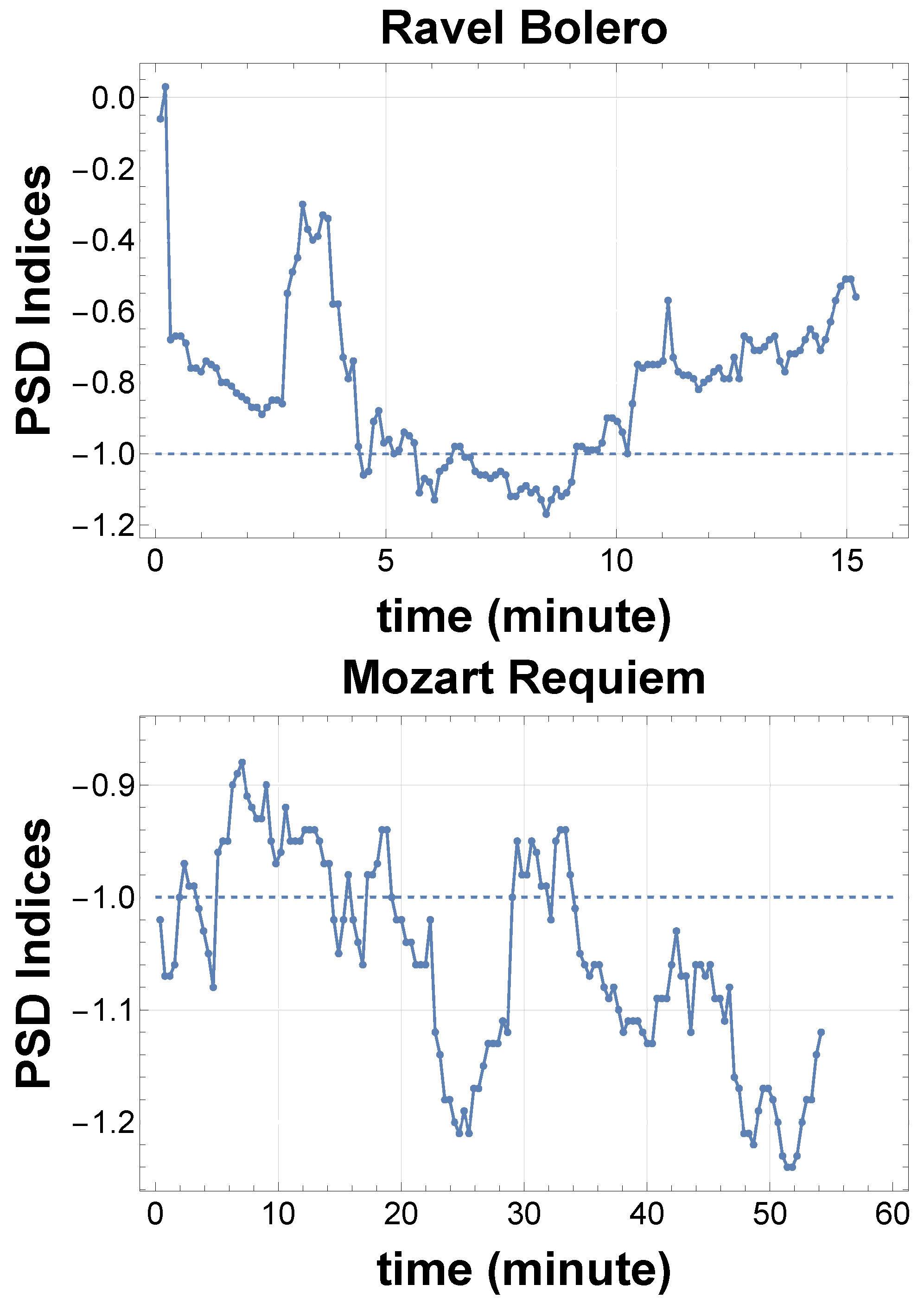

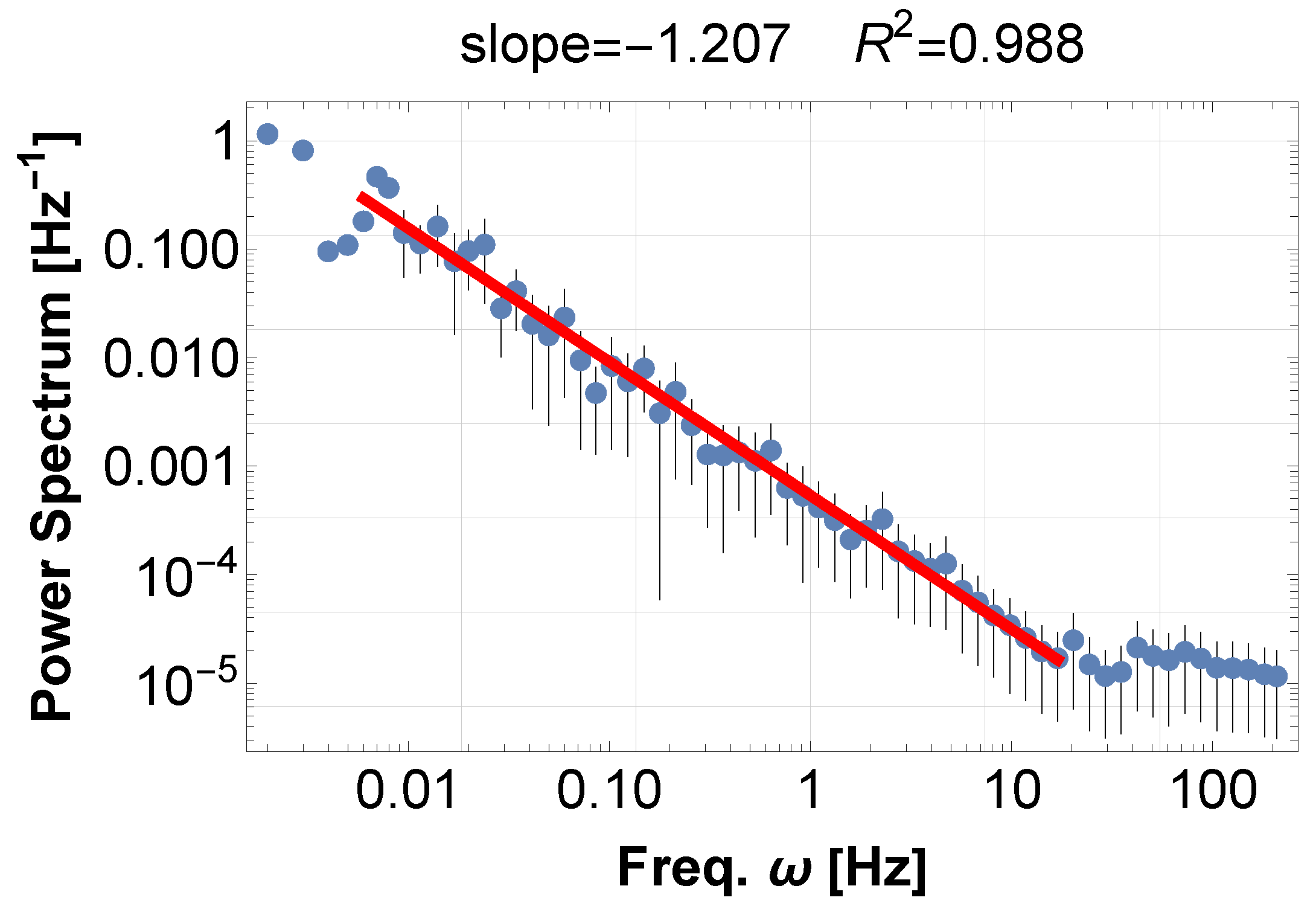

- Low-frequency signal continues without limit: The power in PSD continues without bound. This implies a divergence in total power, as each octave contributes equally to the energy. Furthermore, if stationary, the system appears to possess an infinitely long memory, according to the Wiener–Khinchin theorem, which relates the PSD to the time correlation function. In particular, the orchestral music exhibits 1/f fluctuations throughout its entire performance, for example, for more than 30 min in Figure 1. This is contrary to the case in layer (A), where the domain of the power in the PSD is one second to a few minutes (0.01 to 1 Hz) [10].

- Arbitrary low-frequency signal arises from a tiny system. In the ordinary argument, the system size determines the limiting frequency by a general-order estimate. From the system size l and the typical wave speed v, the maximum correlation time scale is of the order . However, the 1/f fluctuation in music violates this general rule. The 100 m music hall and the sound speed only yield a characteristic timescale of 0.3 s or several Hz. On the contrary, the fluctuation of music 1/f continues for an hour or more. Therefore, we speculate that 1/f fluctuation in music is not an intrinsic property but something secondary among many waves, such as interference between them.

- In the music, 1/f fluctuation appears in the PSD for the data squared or zero-crossing time series; the original data never shows 1/f fluctuations. This fact has been widely appreciated since the pioneering work [8], as if it were self-evident. However, this is strange, as the original layer (A) directory exhibits 1/f fluctuations without any manipulation. Sometimes extra 1/f fluctuations may be generated in the later layers (B) and (C). The same property, the necessity of square operation, appears in economic data and some astrophysical 1/f fluctuations, while many others exhibit direct 1/f fluctuations. What is the difference?

3. Synchronization Mechanism: Orchestral Unison and the Stochastic Kuramoto Model

3.1. The Kuramoto Framework

3.2. From Phase to Sound Signal

3.3. Numerical Simulation

- The partial sum over several in Equation (10) still shows 1/f fluctuations if squared.

- Furthermore, a single variable still shows 1/f fluctuations if self-superposed with the delayed data and squared. This provides a notable contrast, as only a single variable itself does not show 1/f fluctuations, even after being squared.

- Even a bare superposition of the variables shows 1/f fluctuations if squared.

3.4. Interpretation

4. Resonance Mechanism: Solo Performance and Acoustic Environments

4.1. Resonant Amplification in Physical Systems

4.2. Solo Sound and Resonance Characteristics Due to Room Reverberation

4.3. Numerical Illustration

4.4. Interpretation

5. Integration of Synchrony and Resonance: Not a Dichotomy

5.1. Unified View of Frequency Accumulation

5.2. SKM Description of Frequency Accumulation

5.3. Phase-Amplitude Interaction Map

5.4. Conclusions

6. More on Music

6.1. More on Layer (B)

6.2. More on Layer (A)

7. Conclusions and Outlook

7.1. Outlook

- Acoustic effects: We considered some simple features of music and sound. In reality, music is full of delicate sound effects that may affect the low-frequency fluctuations through resonance and synchronization. These include the tone color or timbre, time delay, spatial extension of sound field, vibrato, humming, glissando, legato, etc. Furthermore, the recorded sound may be processed using various techniques, including reverb, chorus, delay, and distortion. We should integrate all of these to achieve complete resolution of the musical 1/f fluctuation.

- Music pink noise from frequency modulation: We emphasized amplitude modulation (AM) in this paper and concentrated on the music performance. However, frequency modulation (FM) and other types of modulation may also yield a long-period structure from the individual short-period fluctuations. We want to explore 1/f fluctuations in music from a much wider perspective [8,9,10,29].

- PSD time series: As the sound data is rich in data points, we can obtain local PSD indices by cutting the whole data into segments. These time series of PSD indices are useful for analyzing variations in the system’s synchronization and resonance. As shown in Figure 7, we can detect a clear transition in musical mood.

- Spatial 1/f fluctuation: We can extend the ordinary notion of 1/f fluctuation in the time domain to the spatial domain as well: fluctuations for the wave number k. A natural approach is to use the Complex Ginzburg–Landau Equation (CGLE) [30], the original equation of the Kuramoto model before phase reduction. In this case, as in the time domain, spatial resonance and synchronization may characterize the long-distance correlations and fluctuations.

7.2. Final Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Case Studies in Acoustic and Natural Environments

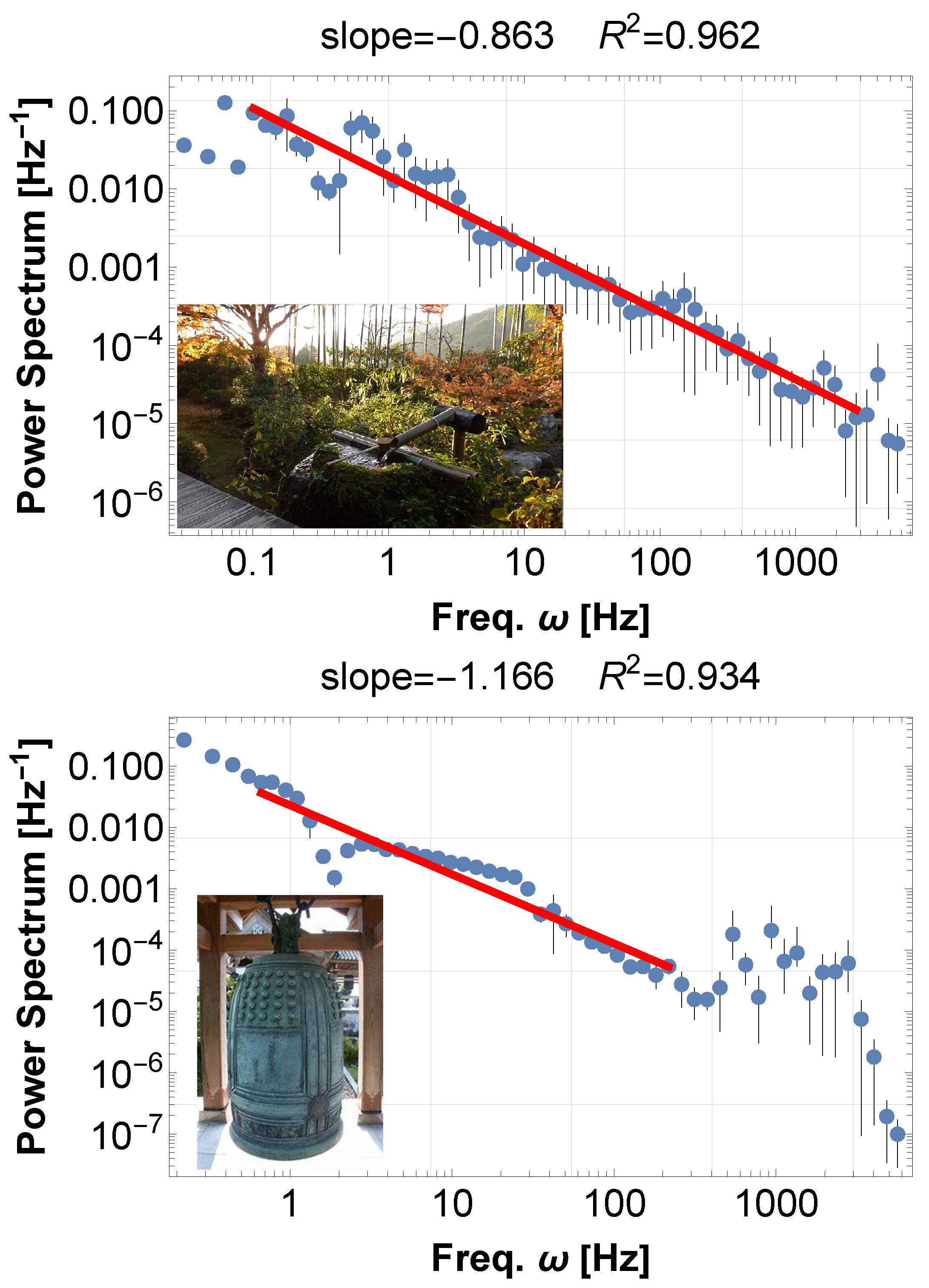

Appendix A.1. The Water Harp Cave at Hosen-in, Kyoto

Appendix A.2. Cretan Sea Soundscape

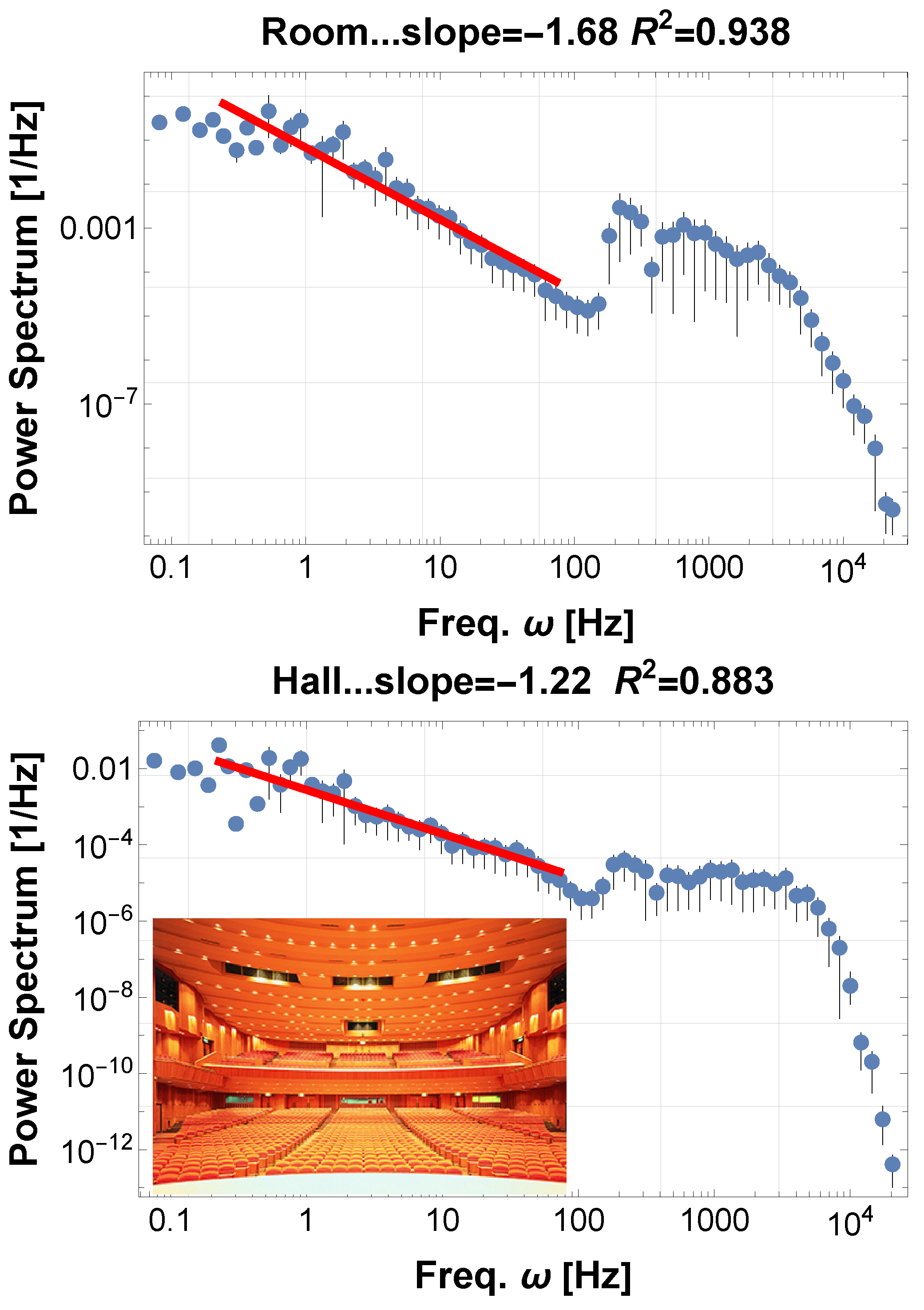

Appendix A.3. Sound in Room and Hall

References

- Milotti, E. 1/f noise: A pedagogical review. arXiv 2002, arXiv:physics/0204033. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.B. The Schottky Effect in Low Frequency Circuits. Phys. Rev. 1925, 26, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M. Low-Frequency Characterization of Music Sounds: Ultra-Bass Richness from the Sound Wave Beats. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.08872. [Google Scholar]

- Morikawa, M.; Nakamichi, A. A simple model for pink noise from amplitude modulations. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamichi, A.; Morikawa, M. Seismic 1/f Fluctuations from Amplitude-Modulated Earth’s Free Oscillation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 93, 024004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M.; Nakamichi, A. Solar Flare 1/f Fluctuations from Amplitude-Modulated Five-Minute Oscillation. Entropy 2023, 25, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M.; Nakamichi, A. Pink Noise in Electric Current from Amplitude Modulations. In Proceedings of the 2023 First International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Electronics and Computational Intelligence (ICAEECI), Online, 19–20 October 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, R.F.; Clarke, J. ’1/f noise’ in music and speech. Nature 1975, 258, 317–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, R.F.; Clarke, J. ’1/f noise’ in music: Music from 1/f noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1978, 63, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitin, D.J.; Chordia, P.; Menon, V. Musical rhythm spectra from Bach to Joplin obey a 1/f power law. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3716–3720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Les Génies du Classique, Volume III no 7 1st Movement: Tchaikovsky Public Domain Historical Recording. 1991. Available online: https://archive.org/details/geniesduclassique_vol3no07?webamp=default (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Petrou, K.; Menegus, S. Unpublished studio recording (soprano and piano), OAK: Kolymbari, Greece, 2023; Unpublished work.

- Kuramoto, Y. Self-entrainment of a population of coupled non-linear oscillators. In International Symposium on Mathematical Problems in Theoretical Physics; Araki, H., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Physics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1975; Volume 39, pp. 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acebrón, J.A.; Bonilla, L.L.; Vicente, C.J.P.; Ritort, F.; Spigler, R. The Kuramoto model: A simple paradigm for synchronization phenomena. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005, 77, 137–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.R.; Majumdar, S.N. Diffusion with Stochastic Resetting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 160601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenschein, B.; Schimansky-Geier, L. Approximate solution to the stochastic Kuramoto model. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 88, 052111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajwani, P.; Jalan, S. Stochastic Kuramoto oscillators with inertia and higher-order interactions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.14874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Musikverein’s Great Hall. Available online: https://www.musikverein.at/grosser-saal/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Vila-Aymerich, G.; Alsina Tarrés, M. A Practical Guide for Room Acoustic Measurements for Voice Research. Voice Speech Rev. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M. Architectural Acoustics, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. [Google Scholar]

- Spens, E.; Burgess, N. A generative model of memory construction and consolidation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartenbeck, P.; Passecker, J.; Hauser, T.U.; FitzGerald, T.H.B.; Kronbichler, M.; Friston, K. Generative replay underlies compositional inference in the hippocampal–prefrontal circuit. Cell 2023, 186, 4885–4897.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.T.; Mattar, M.G.; Daw, N.D. A recurrent network model of planning explains prefrontal–hippocampal interactions. Nat. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, T.T.; Jones, M.N.; Todd, P.M. Optimal foraging in semantic memory. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 119, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, N.B.; Petersson, K.M.; Fransson, P.; Ingvar, M. Neural evidence of switch processes during semantic and phonetic foraging in human memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2312462120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schacter, D.L. The future of memory: Remembering, imagining, and the brain. Neuron 2012, 76, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.Y.; Kaneko, K. Collective 1/f fluctuation by pseudo-Casimir-invariants. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.09158. [Google Scholar]

- Hsü, K.J.; Hsü, A.J. Fractal geometry of music. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 938–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranson, I.S.; Kramer, L. The world of the complex Ginzburg-Landau equation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2002, 74, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M. Quantum Fluctuations in Vacuum Energy: Cosmic Inflation as a Dynamical Phase Transition. Universe 2022, 86, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, M.B. Public Domain Historical Recording, Conducted by Eugene Ormandy. 1955. Available online: https://archive.org/details/cbs-8503-ravel-o-bolero-eugene-ormandy (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Mozart, W.A. Requiem in D Minor, K. 626. Public Domain Historical Recording. 2021. Available online: https://archive.org/details/phil-802-862-ly-mozart-o-requiem-kv-626-colin-davis (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Hosen-in Temple. 2025. Available online: http://www.hosenin.net/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Enko-ji Temple. 2025. Available online: https://www.enkouji.jp/en/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

| odd n-th power | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 |

| slopes | 0.84 | −0.20 | −0.15 | 0.09 |

| even n-th power | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 |

| slopes | −1.27 | −1.15 | −0.89 | −0.68 |

| Transformation | PSD Indices |

|---|---|

| Original Signal: # | 0.25 |

| Squared Signal: | −1.25 |

| Absolute value: | −1.3 |

| Rectification: Max | −1.28 |

| Negative-rectification: Min | −1.27 |

| thresholding above : # | −1.24 |

| anti-thresholding below mean but positive: | |

| # Max(# | −0.89 |

| thresholding timing: | −1.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nakamichi, A.; Uesaka, I.; Morikawa, M. Dynamic Synchronization and Resonance as the Origin of 1/f Fluctuations—Amplitude Modulation Across Music and Nature. Entropy 2026, 28, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010038

Nakamichi A, Uesaka I, Morikawa M. Dynamic Synchronization and Resonance as the Origin of 1/f Fluctuations—Amplitude Modulation Across Music and Nature. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakamichi, Akika, Izumi Uesaka, and Masahiro Morikawa. 2026. "Dynamic Synchronization and Resonance as the Origin of 1/f Fluctuations—Amplitude Modulation Across Music and Nature" Entropy 28, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010038

APA StyleNakamichi, A., Uesaka, I., & Morikawa, M. (2026). Dynamic Synchronization and Resonance as the Origin of 1/f Fluctuations—Amplitude Modulation Across Music and Nature. Entropy, 28(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010038