Improving Multivariate Time-Series Anomaly Detection in Industrial Sensor Networks Using Entropy-Based Feature Aggregation

Abstract

1. Introduction

- This work employs a graph model to reveal hidden structures in complex industrial systems by examining sensor interaction relationships.

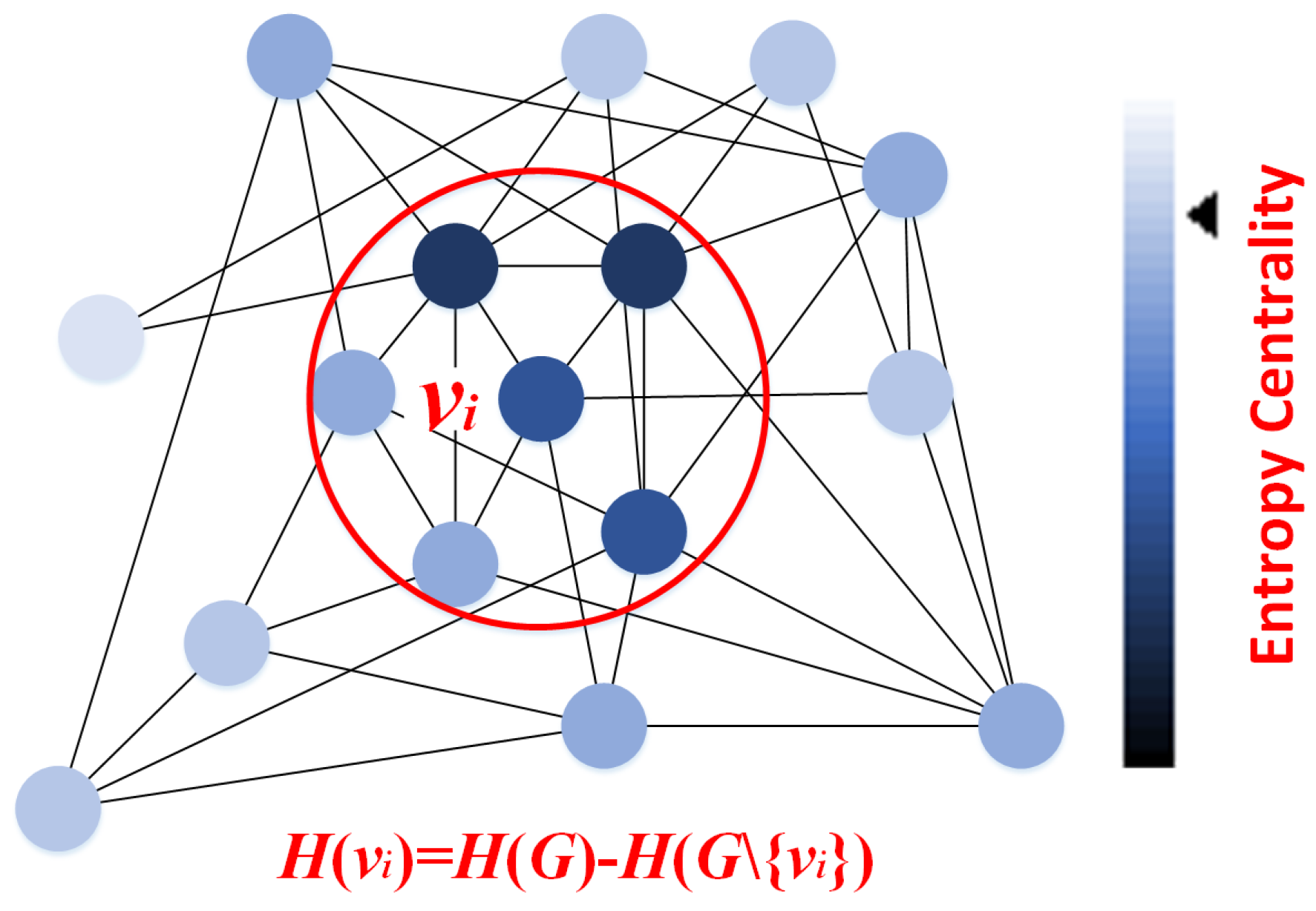

- This work introduces Entropy Centrality-based Graph Attention, which screens each node’s neighbors by analyzing entropy decay strength in the graph’s structure.

- Experiments have shown that this method enhances the efficiency of anomaly detection tasks.

2. Problem Statement

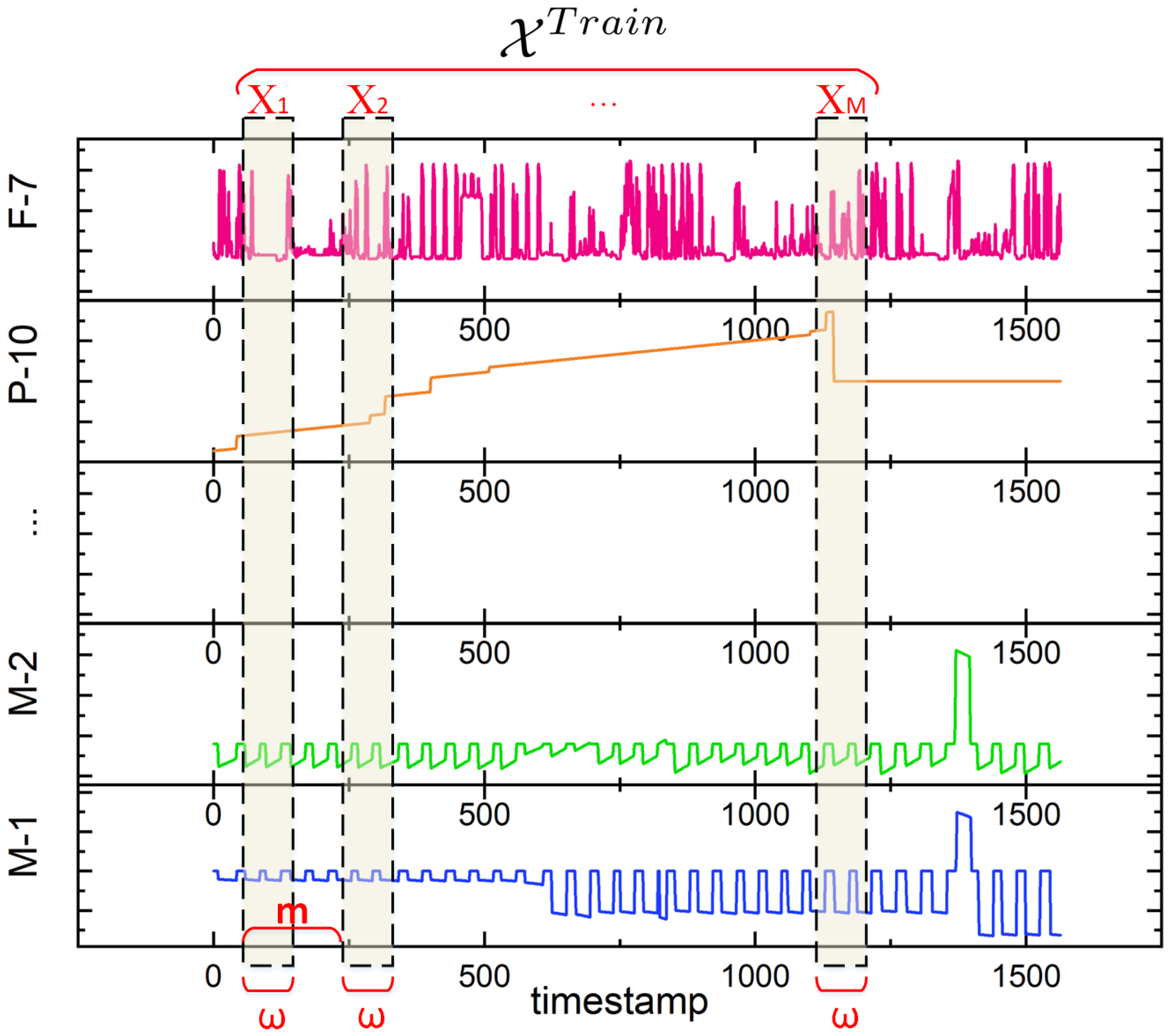

2.1. Multivariate Time-Series Data

2.2. Graph Model

3. Method

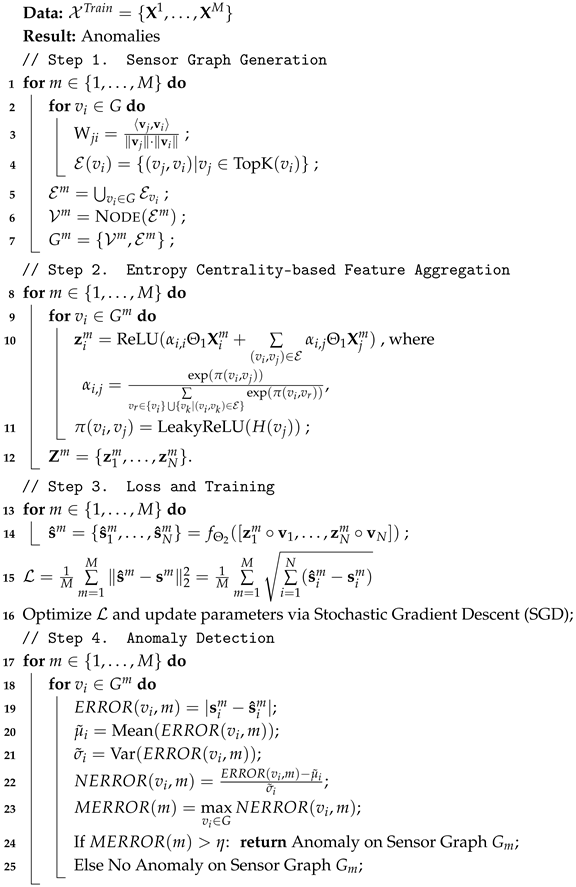

- Step 1. Sensor Graph Generation utilizes directed graphs to extract implicit relationships among sensors in complex industrial systems, selecting the top K related nodes for each node.

- Step 2. Entropy Centrality-based Feature Aggregation integrates all preceding modules within a graph neural network framework by employing an entropy-based attention module that gathers information from related nodes and represents each node accordingly.

- Step 3. Loss and Training trains and updates parameters vis gradient descent.

- Step 4. Anomaly Detection implements anomaly detection by calculating the mean deviation between predicted and expected values.

3.1. Sensor Graph Generation

3.1.1. Representing Nodes

3.1.2. Representing Edges

3.2. Entropy Centrality-Based Feature Aggregation

| Algorithm 1: greenGraph Entropy Function |

|

3.3. Loss and Training

3.4. Anomaly Detection

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

- The Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) dataset [32] encompasses soil samples and telemetry data from NASA’s Mars Rover.

- The Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) dataset [33] is analogous to SMAP. MSL includes sensor and actuator data from the Mars Rover. However, the dataset is distinguished by a high prevalence of trivial sequences.

- The Secure Water Treatment (SWaT) dataset [34] is derived from a real-world water treatment plant, comprising 7 days of normal operation and 4 days of abnormal operation. It incorporates sensor readings (e.g., water level, flow rate) and actuator commands (e.g., valve and pump control).

- The Water Distribution (WADI) dataset [35] is an extension of the SWaT system. The WADI dataset integrates more than twice the number of sensors and actuators compared to the SWaT model. The dataset spans a longer period, with 14 days of normal operation and 2 days of attack scenarios.

| Algorithm 2: greenAnomaly Detection |

|

4.2. Baselines

- IsolationForest [36]: IsolationForest is an unsupervised anomaly detection algorithm that focuses on isolating anomalies rather than profiling normal data. It constructs random decision trees to separate outliers, which require fewer splits due to their unique characteristics. This algorithm is efficient, exhibiting low linear time complexity, and performs well on high-dimensional datasets without requiring distance calculations.

- LSTM [37]: LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) is a recurrent neural network (RNN) architecture designed to capture long-term dependencies in sequential data. It utilizes specialized memory cells with input, output, and forget gates to control information flow, thereby preventing vanishing gradients in deep learning.

- LSTM-NDT [38]: LSTM-NDT enhances traditional LSTM by integrating adaptive thresholding for anomaly detection. It dynamically adjusts decision boundaries in time-series data, improving robustness against noise while maintaining sensitivity to true anomalies.

- MAD-GAN [39]. MAD-GAN is a GAN-based multivariate time-series anomaly detection method. It employs adversarial training between a generator and a discriminator to model the normal data distribution using reconstruction error for anomaly identification. Its strength lies in capturing intricate spatiotemporal dependencies, making it suitable for applications like industrial IoT. In a typical implementation, an LSTM encoder analyzes local and global anomaly patterns within high-dimensional time-series data.

- MTAD-GAT [40]: MTAD-GAT detects anomalies in interdependent sensors by modeling relationships via GAT. It combines feature reconstruction and forecasting errors, excelling in industrial IoT and system monitoring.

- DAGMM [41]: DAGMM is an unsupervised anomaly detection model that combines deep autoencoders with Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs). It jointly optimizes dimensionality reduction and density estimation via end-to-end training, leveraging reconstruction error and low-dimensional features to identify anomalies effectively

- GDN [42]: GDN is a novel GNN framework that learns sensor dependencies via attention-based graph structure learning and detects anomalies by scoring deviations from learned patterns, achieving interpretability and superior accuracy on water treatment datasets

- OmniAnomaly [43]: OmniAnomaly is a robust stochastic recurrent neural network for multivariate time-series anomaly detection. It learns standard patterns through stochastic variable connections and a planar normalizing flow, utilizing reconstruction probabilities to identify and interpret anomalies, achieving a state-of-the-art F1-Score.

- USAD [44]: USAD is an unsupervised anomaly detection framework characterized by an adversarial training architecture. USAD is capable of achieving both efficient learning and high detection accuracy.

- ATUAD [45]: ATUAD is an unsupervised anomaly detection model that integrates adversarial training with the Transformer architecture to amplify subtle anomalies and enhance robustness.

- MSCRED [46]: MSCRED leverages a multi-scale convolutional recurrent encoder–decoder architecture to achieve effective spatio-temporal modeling for end-to-end anomaly detection.

- MSAD [47]: MSAD refers to the multivariate time series based on multi-standard fusion, which understands the data by analyzing the data density and sample spacing.

4.3. Parameters

4.4. Data Preprocessing and Evaluation Metrics

4.4.1. Data Preprocessing

4.4.2. Evaluation Metrics

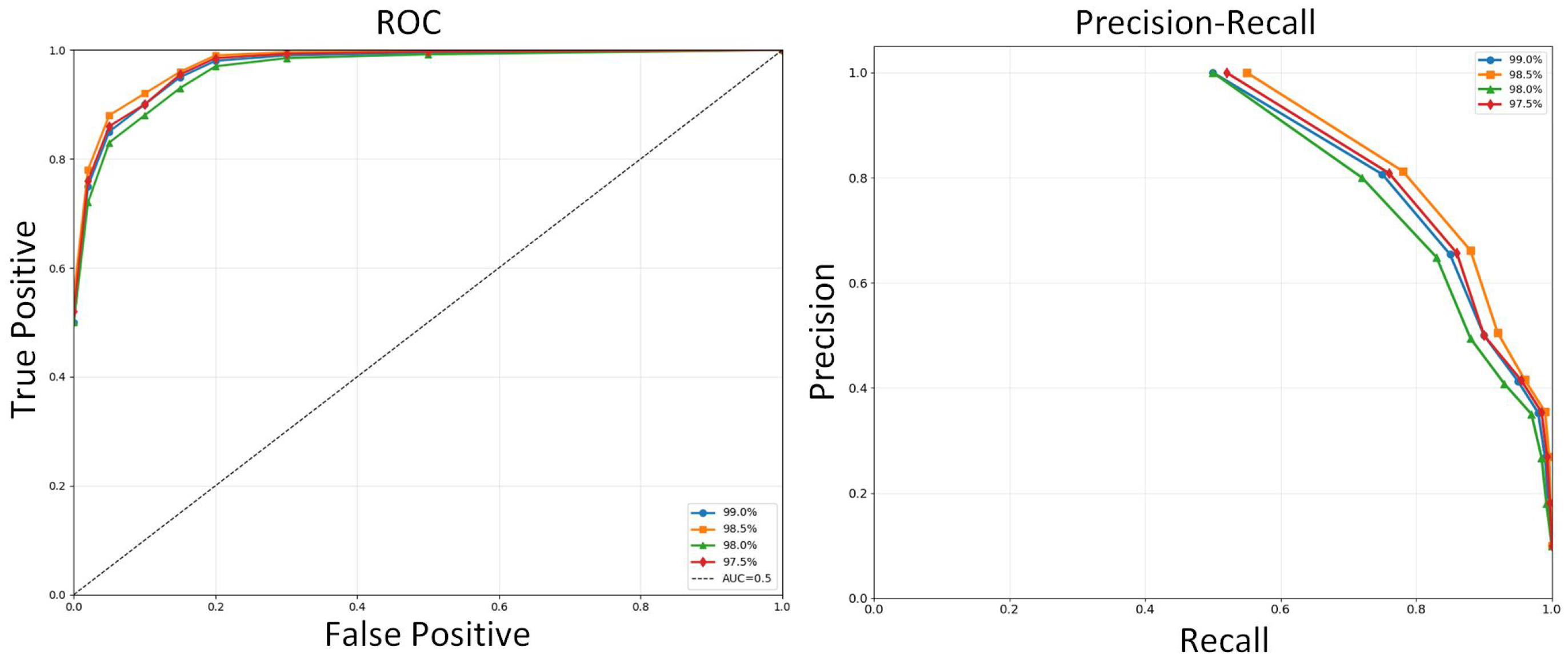

4.5. Results

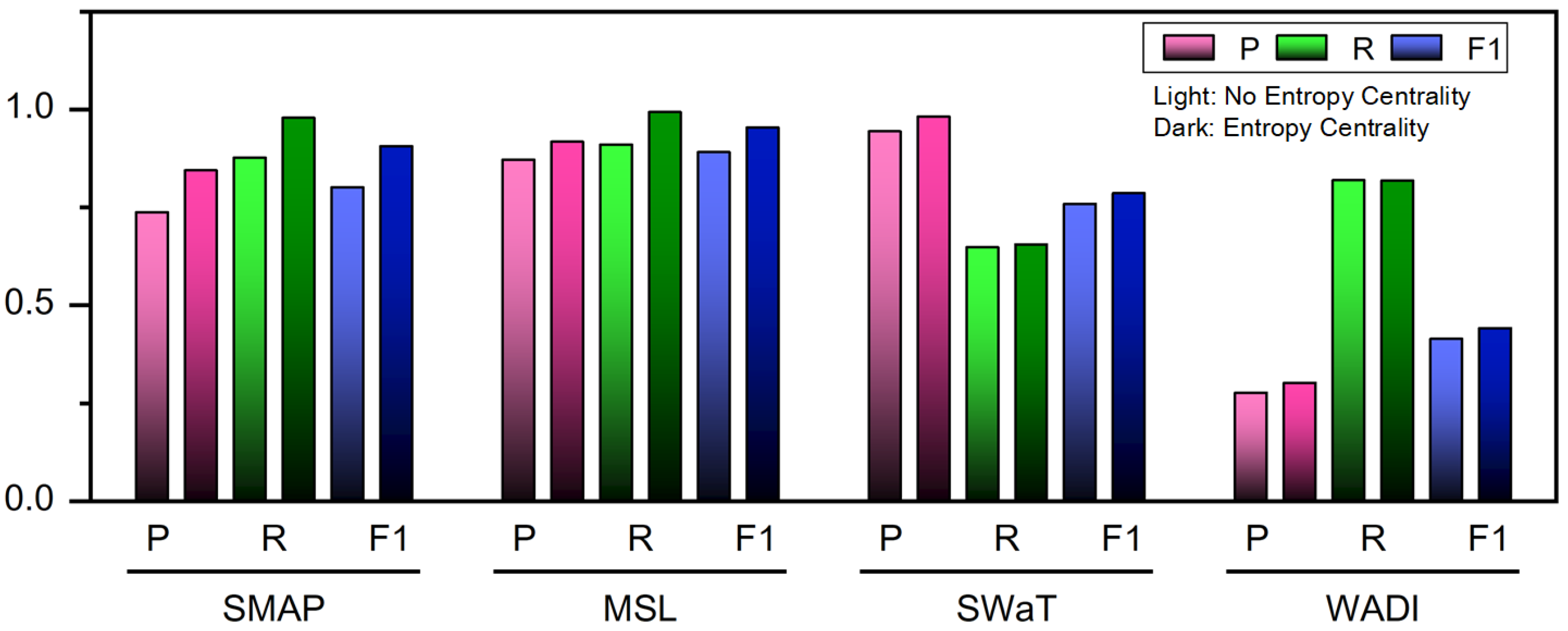

4.6. Ablation Experiment

4.7. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rafique, S.H.; Abdallah, A.; Musa, N.S.; Murugan, T. Machine learning and deep learning techniques for internet of things network anomaly detection—Current research trends. Sensors 2024, 24, 1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Tang, Y.; Chu, L. Generative adversarial networks for prognostic and health management of industrial systems: A review. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 253, 124341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Kataria, A.; Kumar, S.; Karar, V. A new generation cyber-physical system: A comprehensive review from security perspective. Comput. Secur. 2025, 148, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, H.; Rawat, A.; Rajavat, A.; Rawat, R. Literature Review Analysis for Cyberattacks at Management Applications and Industrial Control Systems. In Information Visualization for Intelligent Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 461–487. Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Information+Visualization+for+Intelligent+Systems+-p-9781394305797 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Rahman, M.M.; Al Shakil, S.; Mustakim, M.R. A survey on intrusion detection system in IoT networks. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Mishra, A. Current research on Internet of Things (IoT) security protocols: A survey. Comput. Secur. 2025, 151, 104310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, J.; Maimone, M. Improving Sequence Traceability During Testing and Review for the Mars Science Laboratory. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 1–8 March 2025; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Janson, N.B. Non-linear dynamics of biological systems. Contemp. Phys. 2012, 53, 137–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmeshu; Jain, V. Non-linear models of social systems. Econ. Political Wkly. 2003, 38, 3678–3685. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, I.; Rusák, Z.; Li, Y. Order beyond chaos: Introducing the notion of generation to characterize the continuously evolving implementations of cyber-physical systems. In Proceedings of the International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Cleveland, OH, USA, 6–9 August 2017; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York City, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 58110, p. V001T02A015. [Google Scholar]

- Papon, P.; Leblond, J.; Meijer, P.H. Physics of Phase Transitions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, L. The theory of phase transitions. Nature 1936, 138, 840–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadasivan, A.; Gananathan, K.; Pal Nesamony Rose Mary, J.D.; Balasubramanian, S. A Systematic Survey of Graph Convolutional Networks for Artificial Intelligence Applications. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 15, e70012. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S.; Zhao, B.; Dong, Z.; Gao, M.; He, Z. GTAD: Graph and temporal neural network for multivariate time series anomaly detection. Entropy 2022, 24, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Hou, Y.; Elwakil, E. Enhanced Prediction of Water Pipeline Failures Using a Novel MTGNN-Based Classification Model for Smart City Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Conference on Technologies for Sustainability (SusTech), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 20–23 April 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.; Wang, Y.; Duan, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, X.; Huang, C.; Tong, Y.; Xu, B.; Bai, J.; Tong, J.; et al. Spectral temporal graph neural network for multivariate time-series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 17766–17778. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, B.Z. The graph fractional Fourier transform in Hilbert space. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2403.10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.O. Mathematics of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT): With Audio Applications; Smith, J., Ed.; Amazon Digital Services: Seattle, WA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, M.; Chen, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, Y. LGAT: A novel model for multivariate time series anomaly detection with improved anomaly transformer and learning graph structures. Neurocomputing 2025, 617, 129024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ma, M.; Liu, Y.; Ding, R.; Li, B.; He, S.; Rajmohan, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, D. Imdiffusion: Imputed diffusion models for multivariate time series anomaly detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.00754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Gou, Z.; Tai, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhou, F. Imputation-based time-series anomaly detection with conditional weight-incremental diffusion models. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Long Beach, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 2742–2751. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, C.; Jiang, X.; Du, X.; Yang, W.; Lu, W.; Wang, X.; Chetty, K. Boundary-enhanced time series data imputation with long-term dependency diffusion models. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 310, 112917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Feng, Z. Few-Shot Graph Anomaly Detection via Dual-Level Knowledge Distillation. Entropy 2025, 27, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Sun, D.; Wei, W. Alleviating the over-smoothing of graph neural computing by a data augmentation strategy with entropy preservation. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 132, 108951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromiley, P.; Thacker, N.; Bouhova-Thacker, E. Shannon entropy, Renyi entropy, and information. Stat. Inf. Ser. 2004, 9, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Li, H.; Zhou, S.; Li, B.; Liu, X. Attention With System Entropy for Optimizing Credit Assignment in Cooperative Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 14775–14787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Liu, Y. A Graph Contrastive Learning Method for Enhancing Genome Recovery in Complex Microbial Communities. Entropy 2025, 27, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greven, A.; Keller, G.; Warnecke, G. Entropy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Lio, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

- Elahi, E.; Anwar, S.; Al-kfairy, M.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Ngueilbaye, A.; Halim, Z.; Waqas, M. Graph attention-based neural collaborative filtering for item-specific recommendation system using knowledge graph. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 266, 126133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Lu, X. Personal Interest Attention Graph Neural Networks for Session-Based Recommendation. Entropy 2021, 23, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, P.; Entekhabi, D.; Njoku, E.; Kellogg, K. The NASA soil moisture active passive (SMAP) mission: Overview. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 July 2010; pp. 3236–3239. [Google Scholar]

- Malin, M.C.; Ravine, M.A.; Caplinger, M.A.; Tony Ghaemi, F.; Schaffner, J.A.; Maki, J.N.; Bell, J.F., III; Cameron, J.F.; Dietrich, W.E.; Edgett, K.S.; et al. The Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mast cameras and descent imager: Investigation and instrument descriptions. Earth Space Sci. 2017, 4, 506–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, A.P.; Tippenhauer, N.O. SWaT: A water treatment testbed for research and training on ICS security. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Workshop on Cyber-Physical Systems for Smart Water Networks (CySWater), Vienna, Austria, 11 April 2016; pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, A.K.; Cavdar, B.; Dogan, R.O.; Ayas, S.; Ozgenc, B.; Ayas, M.S. A hybrid CNN-LSTM framework for unsupervised anomaly detection in water distribution plant. In Proceedings of the 2023 Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications Conference (ASYU), Sivas, Turkey, 11–13 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.T.; Ting, K.M.; Zhou, Z.H. Isolation forest. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, Pisa, Italy, 15–19 December 2008; pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, P.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Anand, G.; Vig, L.; Agarwal, P.; Shroff, G. LSTM-based encoder-decoder for multi-sensor anomaly detection. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2020, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, D.; Jin, B.; Shi, L.; Goh, J.; Ng, S.K. MAD-GAN: Multivariate anomaly detection for time series data with generative adversarial networks. In International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 703–716. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Duan, J.; Huang, C.; Cao, D.; Tong, Y.; Xu, B.; Bai, J.; Tong, J.; Zhang, Q. Multivariate time-series anomaly detection via graph attention network. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Sorrento, Italy, 17–20 November 2020; pp. 841–850. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, B.; Song, Q.; Min, M.R.; Cheng, W.; Lumezanu, C.; Cho, D.; Chen, H. Deep Autoencoding Gaussian Mixture Model for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, A.; Hooi, B. Graph Neural Network-Based Anomaly Detection in Multivariate Time Series. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.06947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, C.; Liu, R.; Sun, W.; Pei, D. Robust Anomaly Detection for Multivariate Time Series through Stochastic Recurrent Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–8 August 2019; pp. 2828–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audibert, J.; Michiardi, P.; Guyard, F.; Marti, S.; Zuluaga, M.A. Usad: Unsupervised anomaly detection on multivariate time series. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual Event, 6–10 July 2020; pp. 3395–3404. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, K.; Liu, Y.; Zou, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, W.; Qian, R. Adversarial Transformer-Based Anomaly Detection for Multivariate Time Series. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 2471–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Song, D.; Chen, Y.; Feng, X.; Lumezanu, C.; Cheng, W.; Ni, J.; Zong, B.; Chen, H.; Chawla, N.V. A deep neural network for unsupervised anomaly detection and diagnosis in multivariate time series data. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 1409–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, H.; Kong, H.; Lu, S.; Li, K. Unsupervised anomaly detection of multivariate time series based on multi-standard fusion. Neurocomputing 2025, 611, 128634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospodarskyy, O.; Martsenyuk, V.; Kukharska, N.; Hospodarskyy, A.; Sverstiuk, S. Understanding the adam optimization algorithm in machine learning. In Proceedings of the CITI’2024: 2nd International Workshop on Computer Information Technologies in Industry 4.0, Ternopil, Ukraine, 12–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goutte, C.; Gaussier, E. A probabilistic interpretation of precision, recall and F-score, with implication for evaluation. In European Conference on Information Retrieval; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Dong, J.; Liu, Y.; Long, M.; Wang, J. Deep Time Series Models: A Comprehensive Survey and Benchmark. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.13278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Datasets | Train | Test | Dimensions | Anomaly Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMAP [32] | 135,183 | 427,617 | 25 (55) | 13.13% |

| MSL [33] | 58,317 | 73,729 | 55 (3) | 10.72% |

| SWaT [34] | 496,800 | 449,919 | 51 (1) | 11.98% |

| WADI [35] | 1,048,571 | 172,801 | 123 (1) | 5.99% |

| Datasets | Sliding Window w | Sliding Step m |

|---|---|---|

| SMAP | 120 | 10 |

| MSL | 95 | 10 |

| SWaT | 50 | 10 |

| WADI | 135 | 10 |

| Method | SMAP | MSL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | |

| IsolationForest [36] | 0.5239 | 0.5907 | 0.5553 | 0.5394 | 0.8654 | 0.6645 |

| LSTM [37] | 0.8941 | 0.7813 | 0.8339 | 0.8545 | 0.8250 | 0.8359 |

| LSTM-NDT [38] | 0.8523 | 0.7326 | 0.7879 | 0.6288 | 1.0000 | 0.7721 |

| MAD-GAN [39] | 0.8157 | 0.9216 | 0.8654 | 0.8516 | 0.9930 | 0.9169 |

| MTAD-GAT [40] | 0.7991 | 0.9991 | 0.8880 | 0.7917 | 0.9824 | 0.8768 |

| DAGMM [41] | 0.8645 | 0.5673 | 0.6851 | 0.8960 | 0.6393 | 0.7462 |

| GDN [42] | 0.7480 | 0.9891 | 0.8518 | 0.9308 | 0.9892 | 0.9591 |

| OmniAnomaly [43] | 0.8130 | 0.9419 | 0.8728 | 0.7848 | 0.9924 | 0.8765 |

| USAD [44] | 0.7480 | 0.9627 | 0.8419 | 0.8710 | 0.9536 | 0.9104 |

| ATUAD [45] | 0.8157 | 0.9999 | 0.8985 | 0.9041 | 0.9999 | 0.9496 |

| MSCRED [46] | 0.8175 | 0.9216 | 0.8664 | 0.8912 | 0.9862 | 0.9363 |

| MSAD [47] | 0.8502 | 0.9066 | 0.8775 | 0.9065 | 0.9626 | 0.9337 |

| This Work | ||||||

| Method | SWaT | WADI | ||||

| P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | |

| IsolationForest [36] | 0.4929 | 0.4495 | 0.4702 | 0.1822 | 0.7824 | 0.2954 |

| LSTM [37] | 0.8615 | 0.8327 | 0.8469 | 0.2063 | 0.7632 | 0.3358 |

| LSTM-NDT [38] | 0.7778 | 0.5109 | 0.6167 | 0.2138 | 0.7823 | 0.3358 |

| MAD-GAN [39] | 0.9593 | 0.6957 | 0.8065 | 0.2233 | 0.9124 | 0.3588 |

| MTAD-GAT [40] | 0.9718 | 0.6957 | 0.8109 | 0.2818 | 0.8012 | 0.4169 |

| DAGMM [41] | 0.8992 | 0.5784 | 0.7040 | 0.2760 | 0.9981 | 0.4324 |

| GDN [42] | 0.9697 | 0.6957 | 0.8101 | 0.2912 | 0.7931 | 0.4260 |

| OmniAnomaly [43] | 0.9782 | 0.6957 | 0.8131 | 0.3158 | 0.6541 | 0.4260 |

| USAD [44] | 0.9977 | 0.6879 | 0.8143 | 0.1873 | 0.8296 | 0.3056 |

| ATUAD [45] | 0.9696 | 0.6957 | 0.8101 | 0.3005 | 0.8286 | 0.4403 |

| MSCRED [46] | 0.9318 | 0.9825 | 0.9565 | 0.2513 | 0.7319 | 0.3741 |

| MSAD [47] | 0.9532 | 0.9943 | 0.9739 | 0.2832 | 0.8356 | 0.4230 |

| This Work | ||||||

| Method | SMAP | MSL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | |

| Entropy Centrality | 0.8452 | 0.9790 | 0.9071 | 0.9182 | 0.9941 | 0.9546 |

| Without Entropy Centrality | 0.7386 | 0.8775 | 0.8021 | 0.8725 | 0.9112 | 0.89143 |

| Method | SWaT | WADI | ||||

| P | R | F1 | P | R | F1 | |

| Entropy Centrality | 0.9828 | 0.6563 | 0.7870 | 0.3029 | 0.8196 | 0.4423 |

| Without Entropy Centrality | 0.945 | 0.6489 | 0.7642 | 0.2781 | 0.8200 | 0.4152 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, B. Improving Multivariate Time-Series Anomaly Detection in Industrial Sensor Networks Using Entropy-Based Feature Aggregation. Entropy 2026, 28, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010014

Wang B. Improving Multivariate Time-Series Anomaly Detection in Industrial Sensor Networks Using Entropy-Based Feature Aggregation. Entropy. 2026; 28(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Bowen. 2026. "Improving Multivariate Time-Series Anomaly Detection in Industrial Sensor Networks Using Entropy-Based Feature Aggregation" Entropy 28, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010014

APA StyleWang, B. (2026). Improving Multivariate Time-Series Anomaly Detection in Industrial Sensor Networks Using Entropy-Based Feature Aggregation. Entropy, 28(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/e28010014