Efficient Circuit Implementations of Continuous-Time Quantum Walks for Quantum Search

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CTQW on Graphs

2.1. Spatial Search on Graphs

2.2. Locality

3. Complete Graph

Spatial Search on Complete Graph

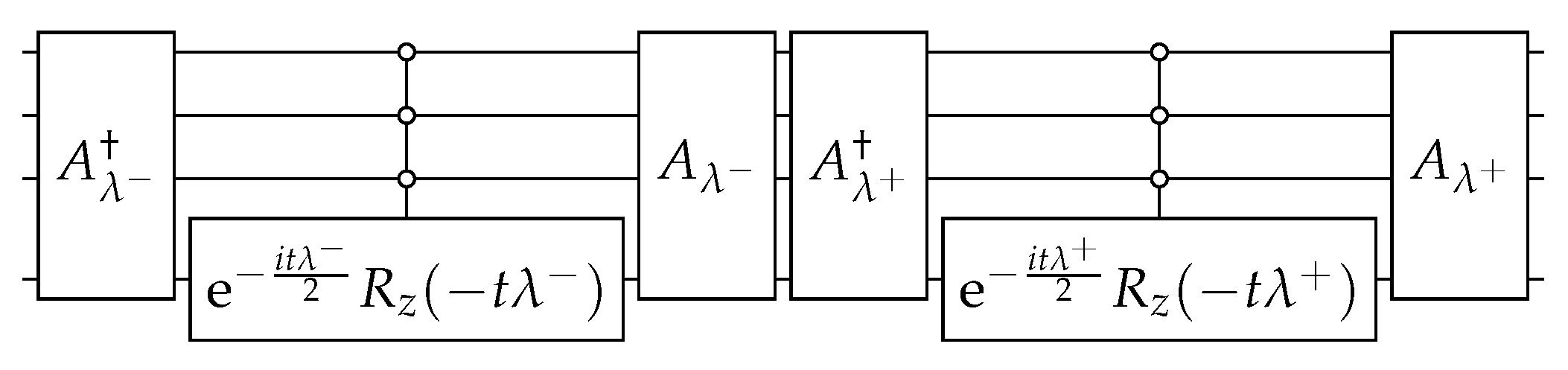

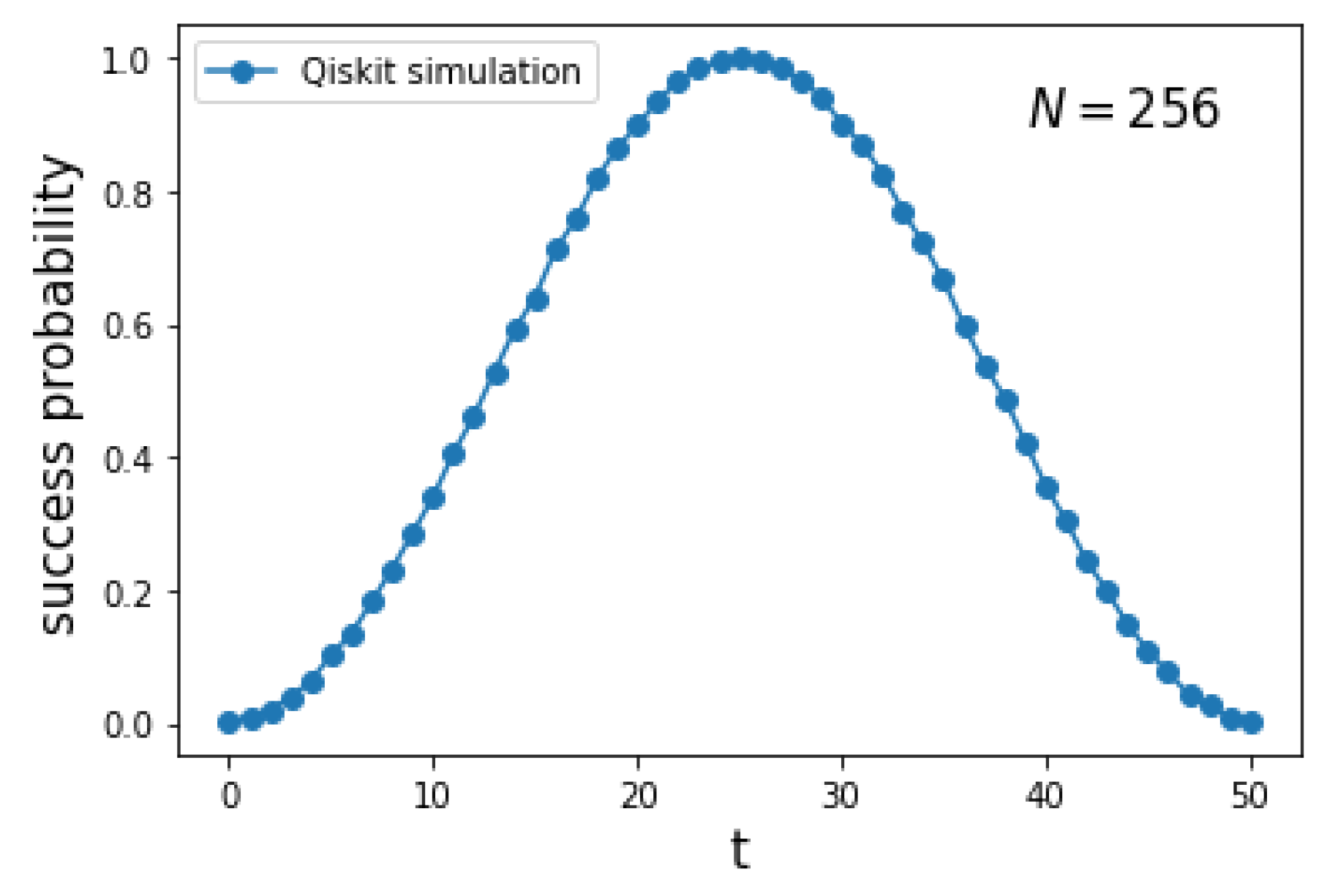

4. Complete Bipartite Graph

Spatial Search on Complete Bipartite Graph

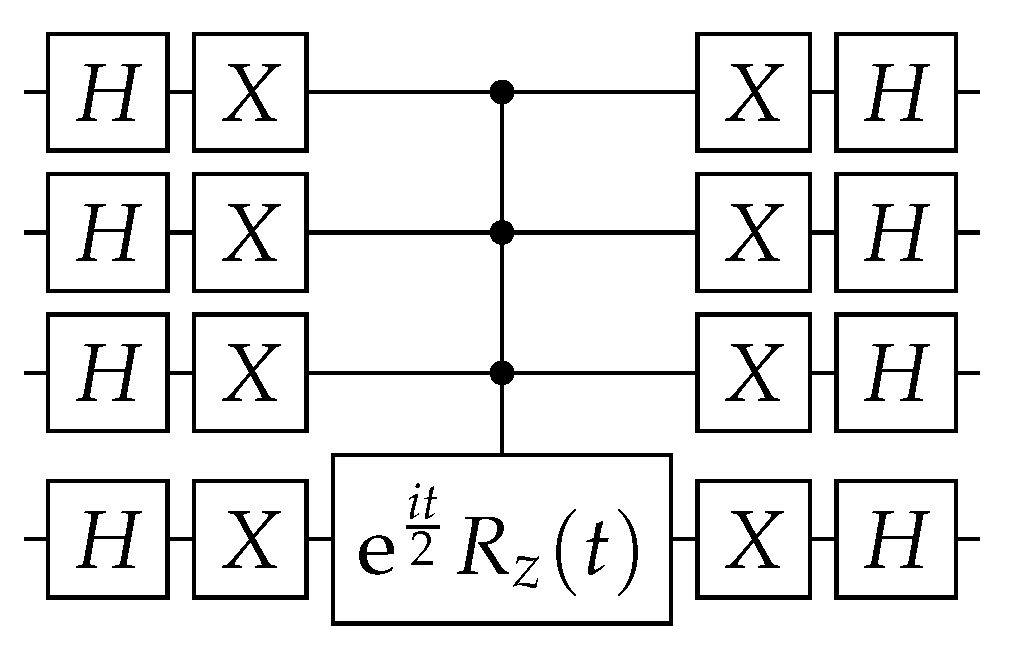

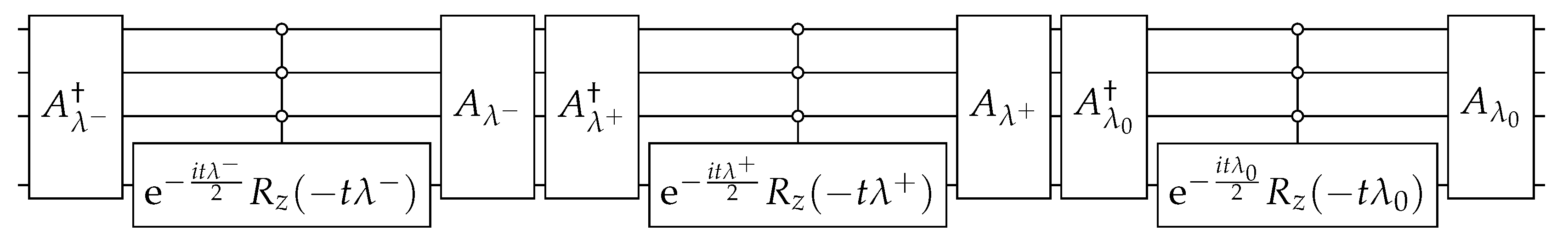

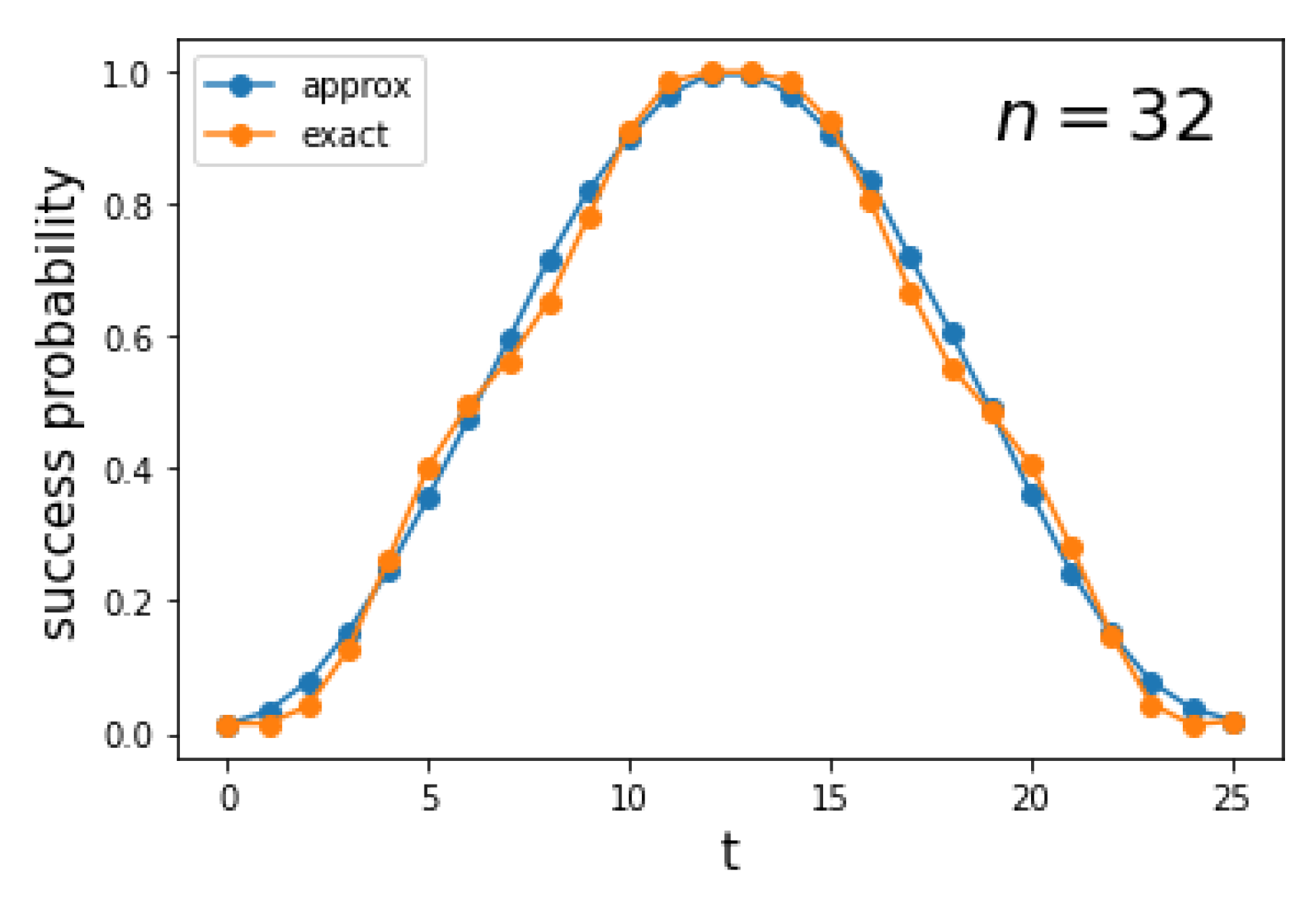

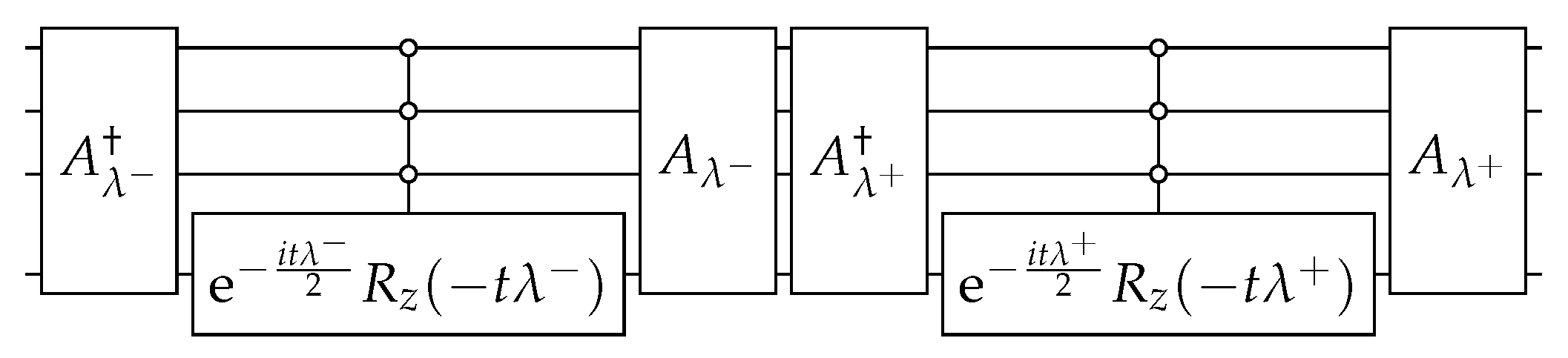

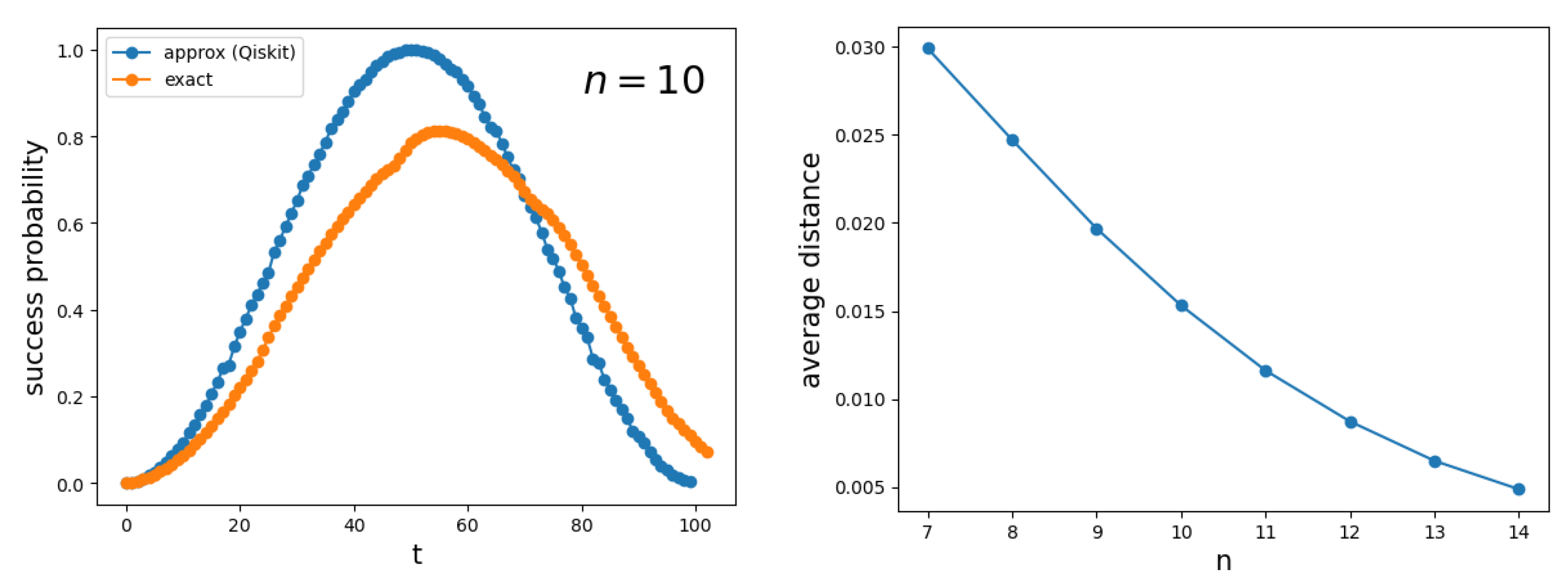

5. Hypercube

Spatial Search on Hypercube

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTQW | Continuous-Time Quantum Walk |

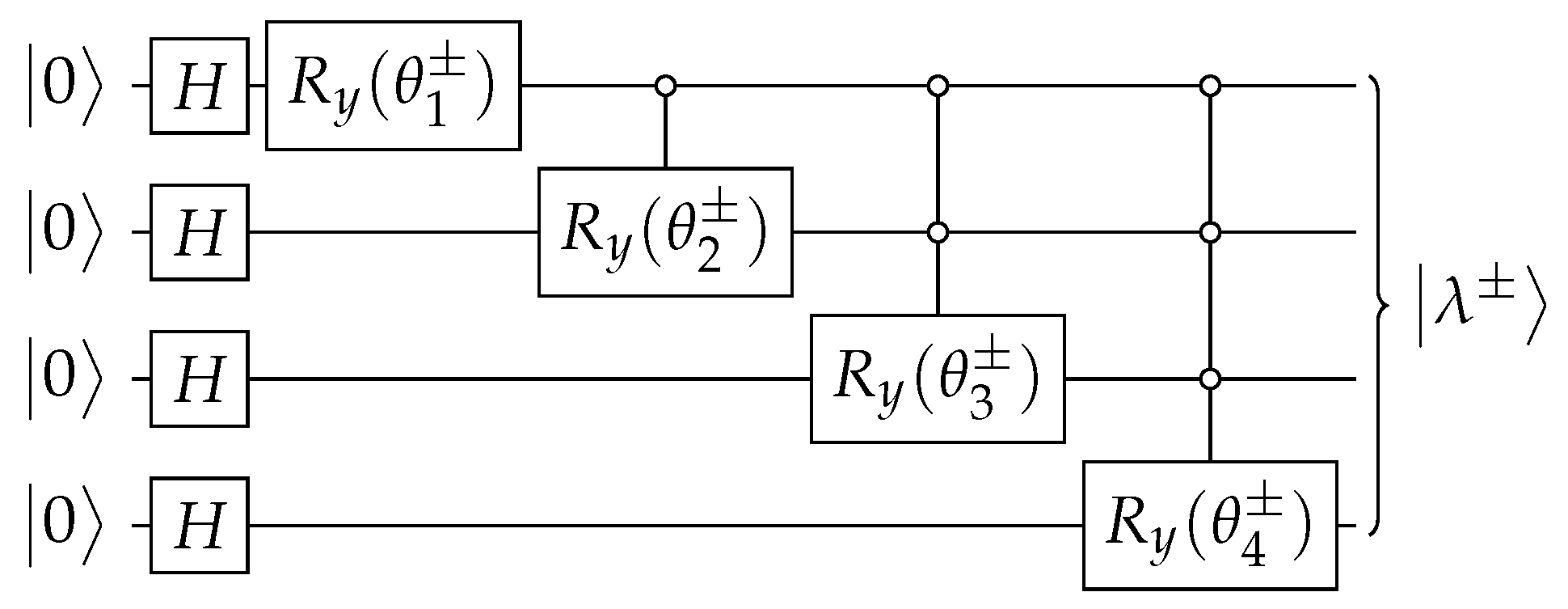

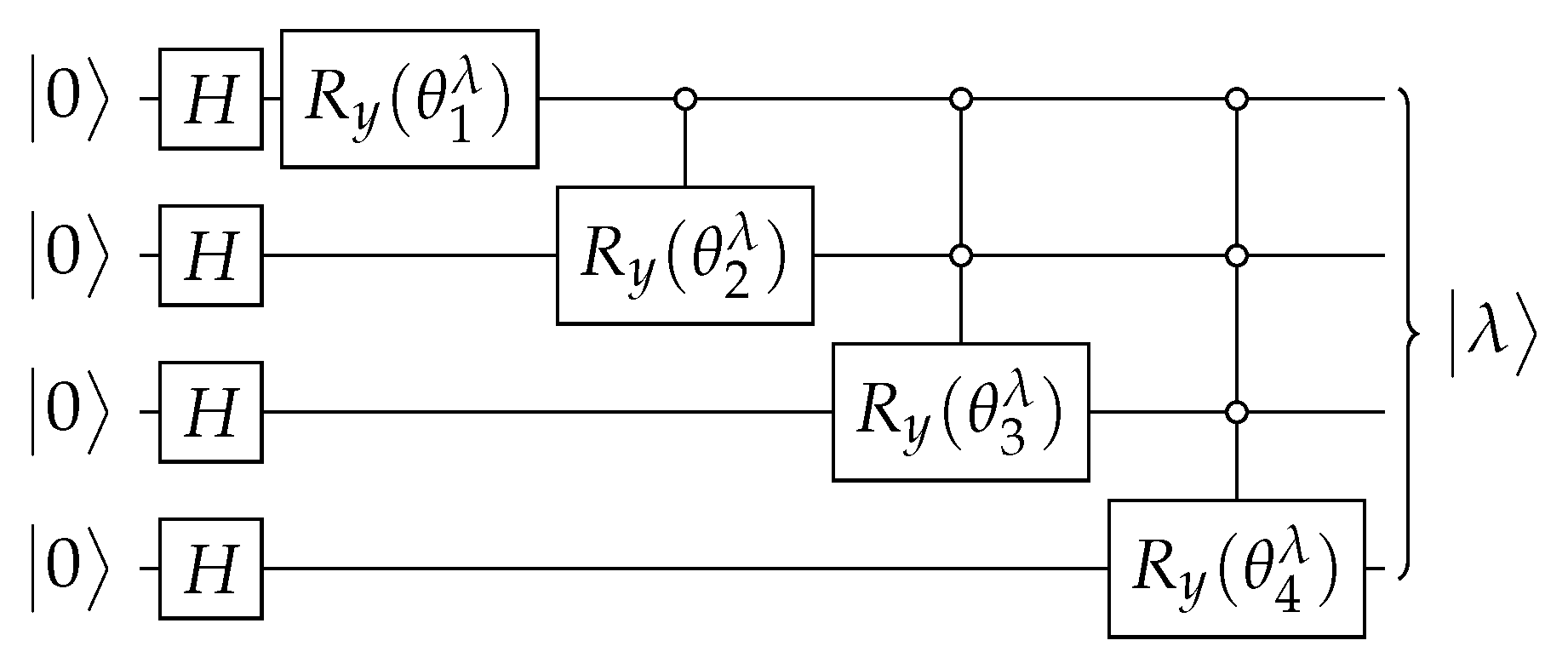

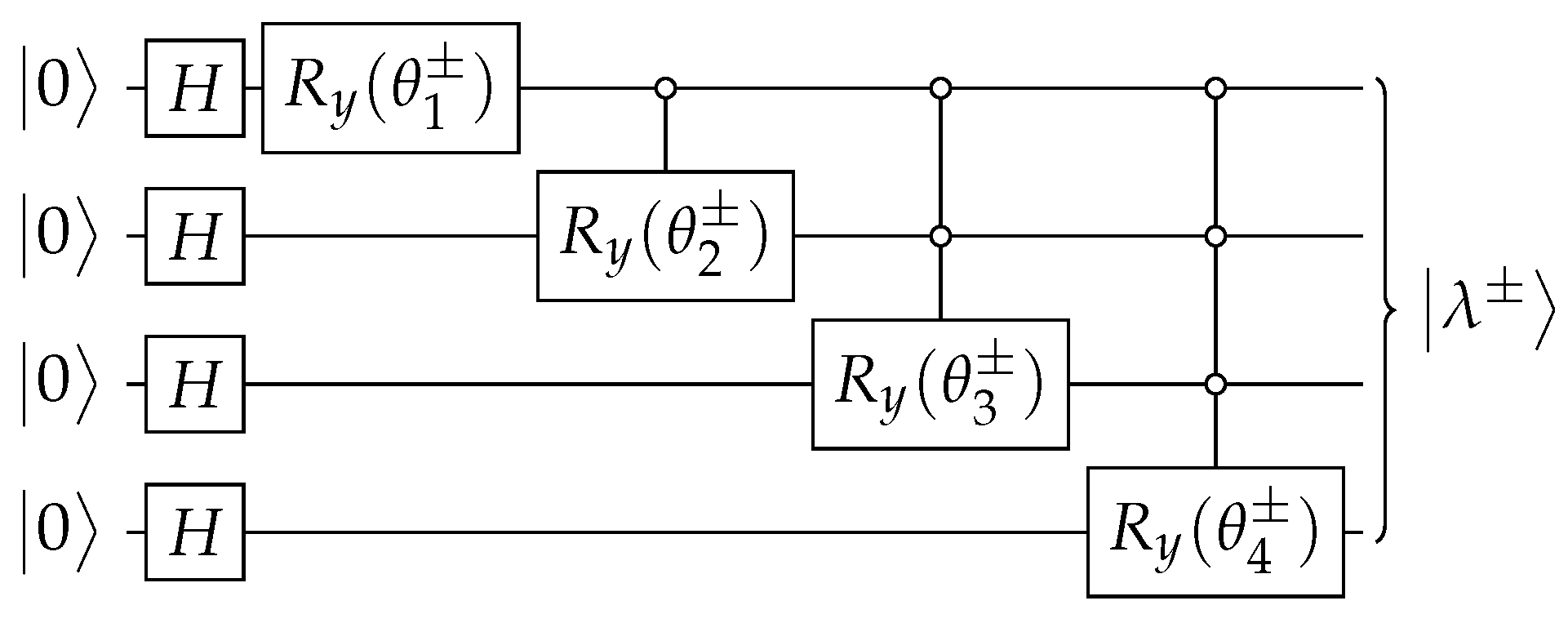

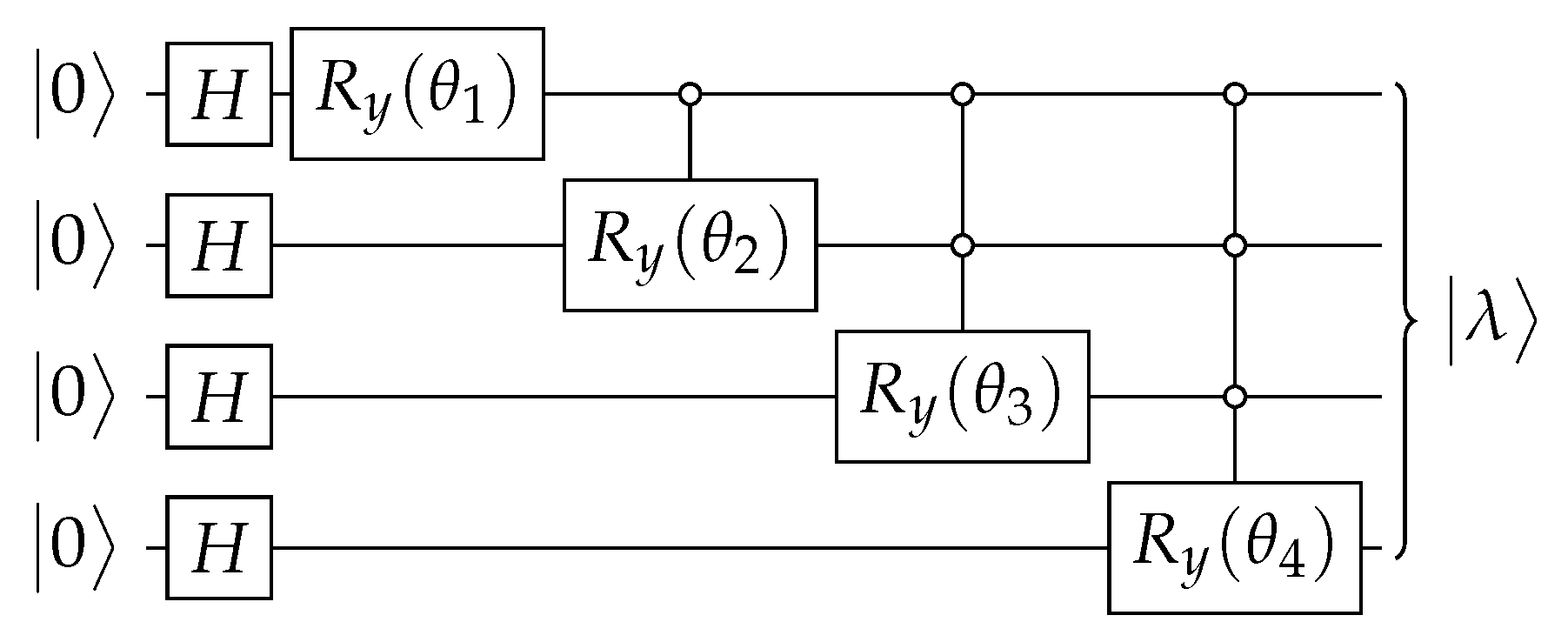

Appendix A. State Preparation

Appendix B. Eigenvectors of the Modified Hamiltonian

References

- Farhi, E.; Gutmann, S. Quantum computation and decision trees. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 58, 915–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A.M.; Goldstone, J. Spatial search by quantum walk. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 70, 022314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agliari, E.; Blumen, A.; Mülken, O. Quantum-walk approach to searching on fractal structures. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 012305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, P.; Tarrataca, L.; Boettcher, S. Continuous-time quantum search on balanced trees. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 93, 032305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osada, T.; Coutinho, B.; Omar, Y.; Sanaka, K.; Munro, W.J.; Nemoto, K. Continuous-time quantum-walk spatial search on the Bollobás scale-free network. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 101, 022310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmi, J.; Rossi, M.A.C.; García-Pérez, G.; Maniscalco, S. Spatial search by continuous-time quantum walks on renormalized Internet networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 2022, 4, 043185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, E.; Goldstone, J.; Gutmann, S. A Quantum Algorithm for the Hamiltonian NAND Tree. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A.M. Universal Computation by Quantum Walk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 180501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, A.M.; Gosset, D.; Webb, Z. Universal Computation by Multiparticle Quantum Walk. Science 2013, 339, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahini, Y.; Steinbrecher, G.R.; Bookatz, A.D.; Englund, D. Quantum logic using correlated one-dimensional quantum walks. npj Quantum Inf. 2018, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadras, S.; Gresch, A.; Groiseau, C.; Wimberger, S.; Summy, G.S. Experimental realization of a momentum-space quantum walk. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 043617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvecchio, M.; Groiseau, C.; Petiziol, F.; Summy, G.S.; Wimberger, S. Quantum search with a continuous-time quantum walk in momentum space. J. Phys. B At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 2020, 53, 065301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Shi, Y.; Xiao, L.; Wang, J.; Joglekar, Y.N.; Xue, P. Experimental realization of continuous-time quantum walks on directed graphs and their application in PageRank. Optica 2020, 7, 1524–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, C.; Tamascelli, D.; Paris, M.G.; Crespi, A. Quantum Spatial Search in Two-Dimensional Waveguide Arrays. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2021, 16, 054036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, D.; Marsh, S.; Wang, K.; Xiao, L.; Wang, J.; Xue, P. Deterministic Search on Star Graphs via Quantum Walks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 050501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.; Loke, T.; Montanaro, A.; Aungskunsiri, K.; Zhou, X.; O’Brien, J.L.; Wang, J.B.; Matthews, J.C.F. Efficient quantum walk on a quantum processor. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loke, T.; Wang, J.B. Efficient quantum circuits for continuous-time quantum walks on composite graphs. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2017, 50, 055303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Chagas, B.; Chaves, R. Quantum Walks in a Superconducting Quantum Computer. In WQUANTUM; Sociedade Brasileira de Computação: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2021; pp. 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharonov, Y.; Davidovich, L.; Zagury, N. Quantum random walks. Phys. Rev. A 1993, 48, 1687–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acasiete, F.; Agostini, F.P.; Moqadam, J.K.; Portugal, R. Implementation of quantum walks on IBM quantum computers. Quantum Inf. Process. 2020, 19, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzongani, U.; Zylberman, J.; Doncecchi, C.E.; Pérez, A.; Debbasch, F.; Arnault, P. Quantum circuits for discrete-time quantum walks with position-dependent coin operator. Quantum Inf. Process. 2023, 22, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulos, K.; Emary, C.; Zuliani, P. Comparison of quantum-walk implementations on noisy intermediate-scale quantum computers. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 022408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing-Bocanegra, A.; Venegas-Andraca, S.E. Circuit implementation of discrete-time quantum walks via the shunt decomposition method. Quantum Inf. Process. 2023, 22, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzoli, L.; Cenedese, G.; Bondani, M.; Benenti, G. Efficient Implementation of Discrete-Time Quantum Walks on Quantum Computers. Entropy 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugão, P.; Portugal, R.; Sabri, M.; Tanaka, H. Multimarked Spatial Search by Continuous-Time Quantum Walk. ACM Trans. Quantum Comput. 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, M.; Benedetti, C.; Olivares, S.; Paris, M.G.A. Generalized quantum-classical correspondence for random walks on graphs. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 104, L030201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, G.A.; Lugão, P.H.G.; Portugal, R. Quantum-walk-based search algorithms with multiple marked vertices. Phys. Rev. A 2021, 103, 062202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.F.T.d.; Posner, D.; Portugal, R. Walking on vertices and edges by continuous-time quantum walk. Quantum Inf. Process. 2023, 22, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Portugal, R.; Moqadam, J.K. Efficient Circuit Implementations of Continuous-Time Quantum Walks for Quantum Search. Entropy 2025, 27, 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27050454

Portugal R, Moqadam JK. Efficient Circuit Implementations of Continuous-Time Quantum Walks for Quantum Search. Entropy. 2025; 27(5):454. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27050454

Chicago/Turabian StylePortugal, Renato, and Jalil Khatibi Moqadam. 2025. "Efficient Circuit Implementations of Continuous-Time Quantum Walks for Quantum Search" Entropy 27, no. 5: 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27050454

APA StylePortugal, R., & Moqadam, J. K. (2025). Efficient Circuit Implementations of Continuous-Time Quantum Walks for Quantum Search. Entropy, 27(5), 454. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27050454