Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics of the Intermediate Dispersive Velocity Equation with Soliton Stability and Chaos

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Gap, Novelty, and Contribution

- Reduced-order nonlinear oscillators with periodic forcing and stochastic perturbations are used to illustrate the generalized stochastic SIdV equation.

- Broad analysis of soliton overlap, multistability, attractor fluctuations, and order–chaos transitions in both deterministic and stochastic contexts is conducted.

- Chaotic features and stability structures are characterized by fractal measurements, power spectra, return maps, surrogate data, and recurrence analysis.

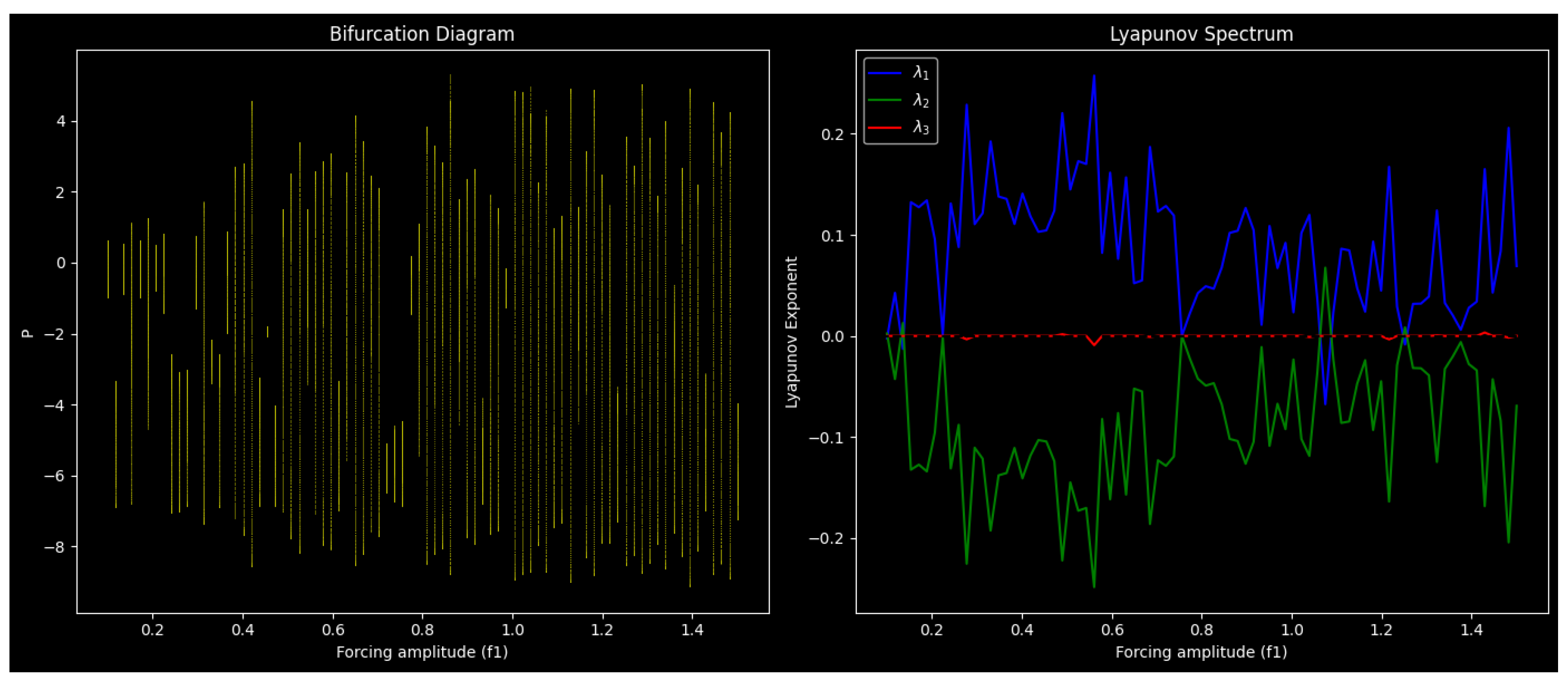

- Dynamical regimes are categorized using bifurcation diagrams alongside Lyapunov spectrum analysis, with an emphasis on noise-induced transitions.

- The results may find use in nonlinear wave control, energy transport in complex media, and noise-assisted signal processing.

2. Mathematical Analysis

2.1. Governing Model

2.2. Dynamical System

3. Results and Discussions

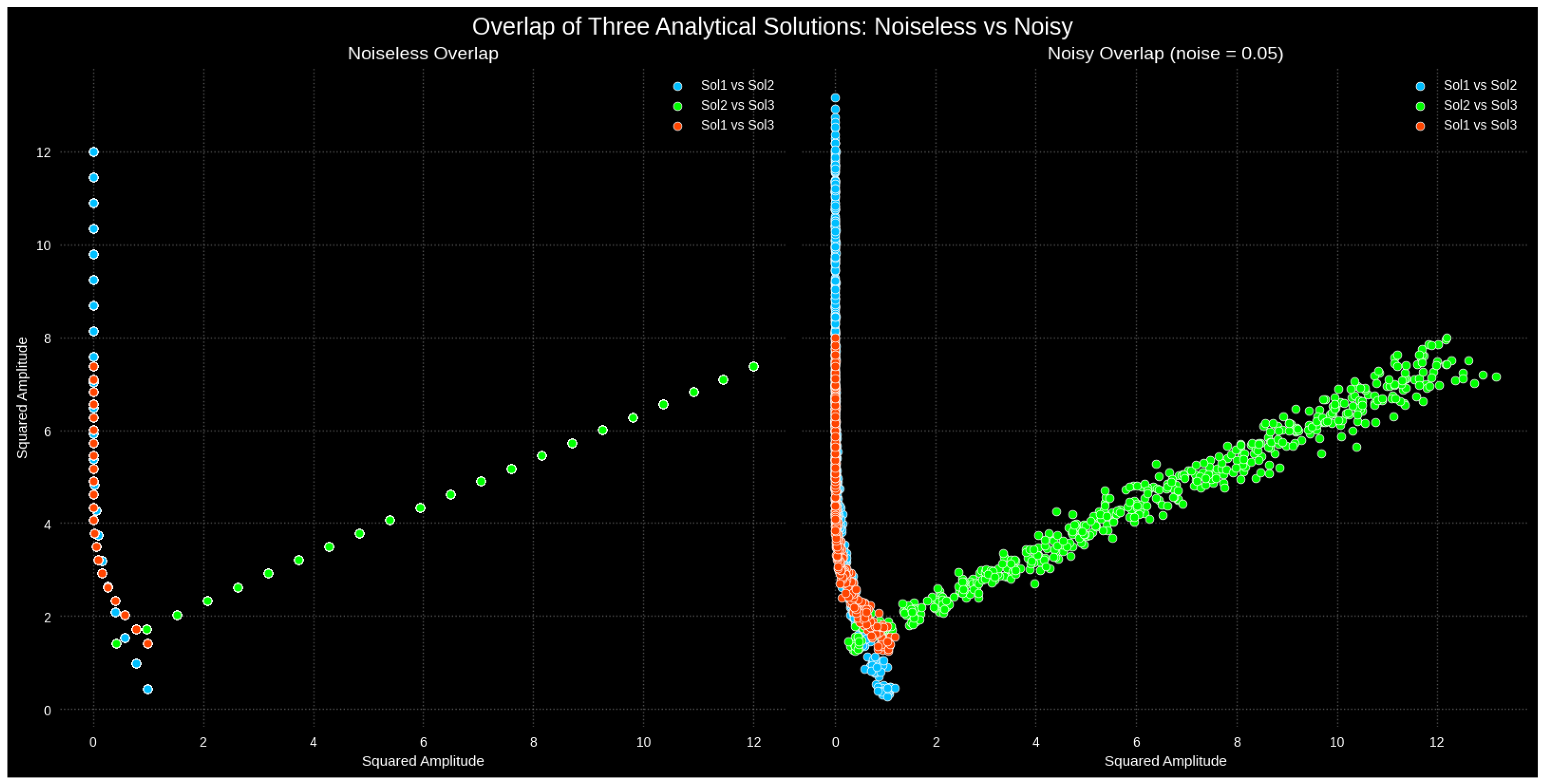

3.1. Soliton Overlap in Deterministic and Stochastic Settings

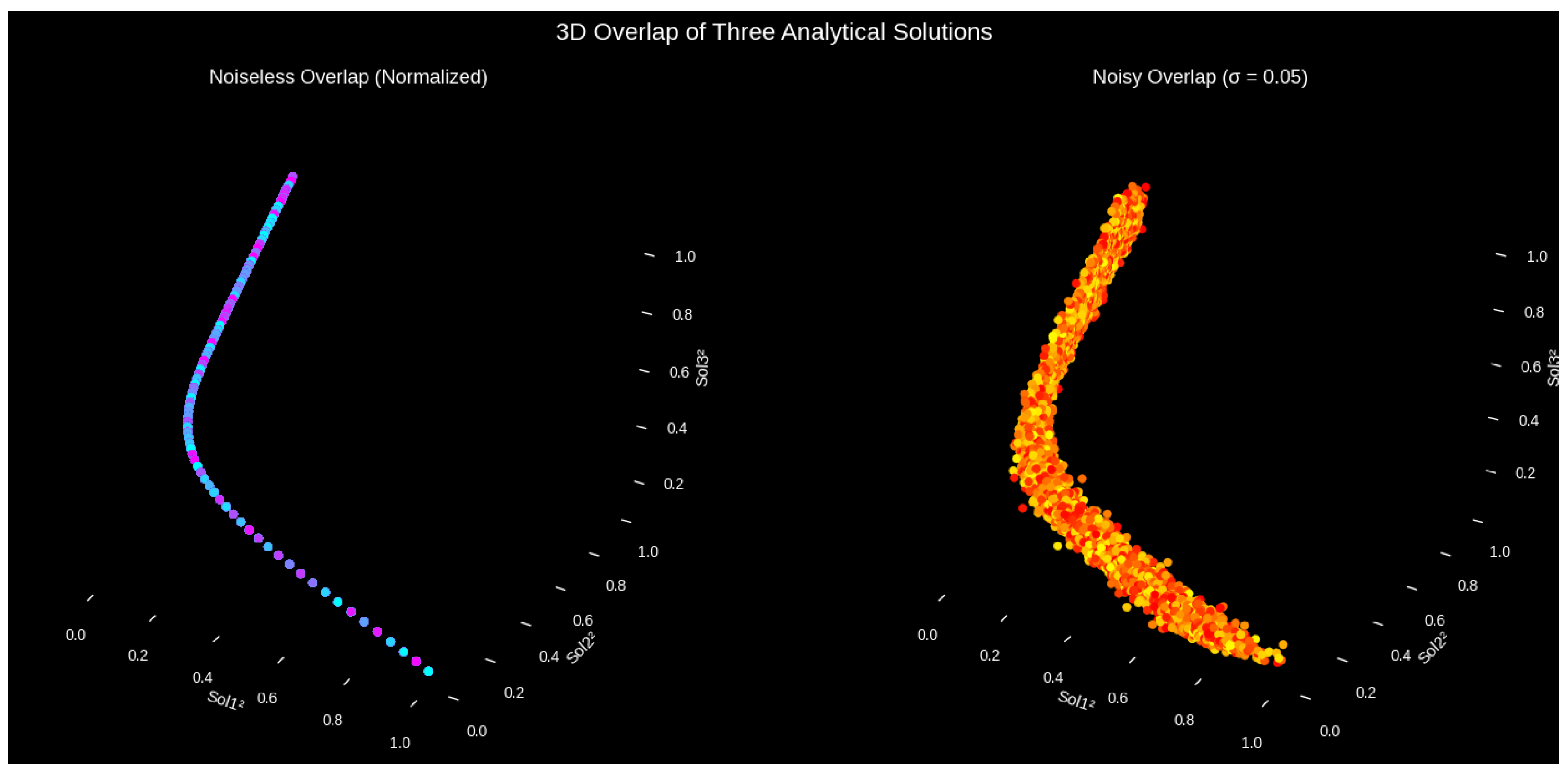

3.1.1. Uncertainty Quantification and Noise-Induced Soliton Stability Analysis

- (a)

- Soliton Stability Under Multiplicative Noise

- (b)

- Polynomial Chaos Expansion for Uncertainty Quantification

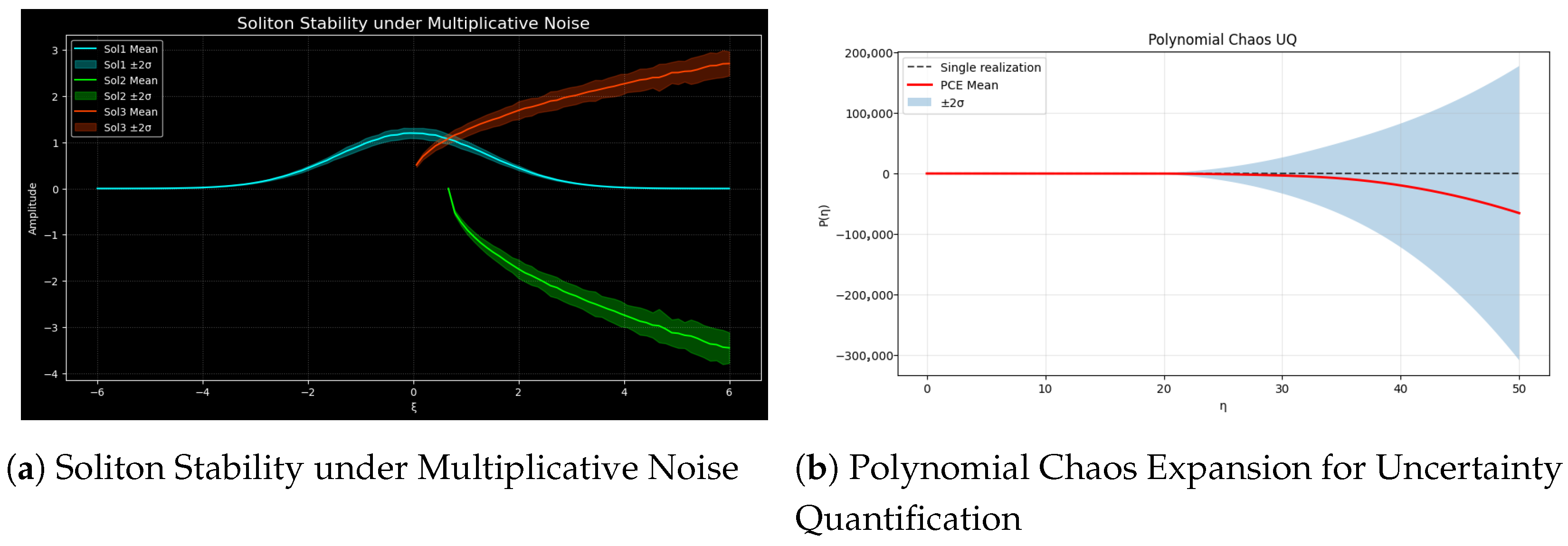

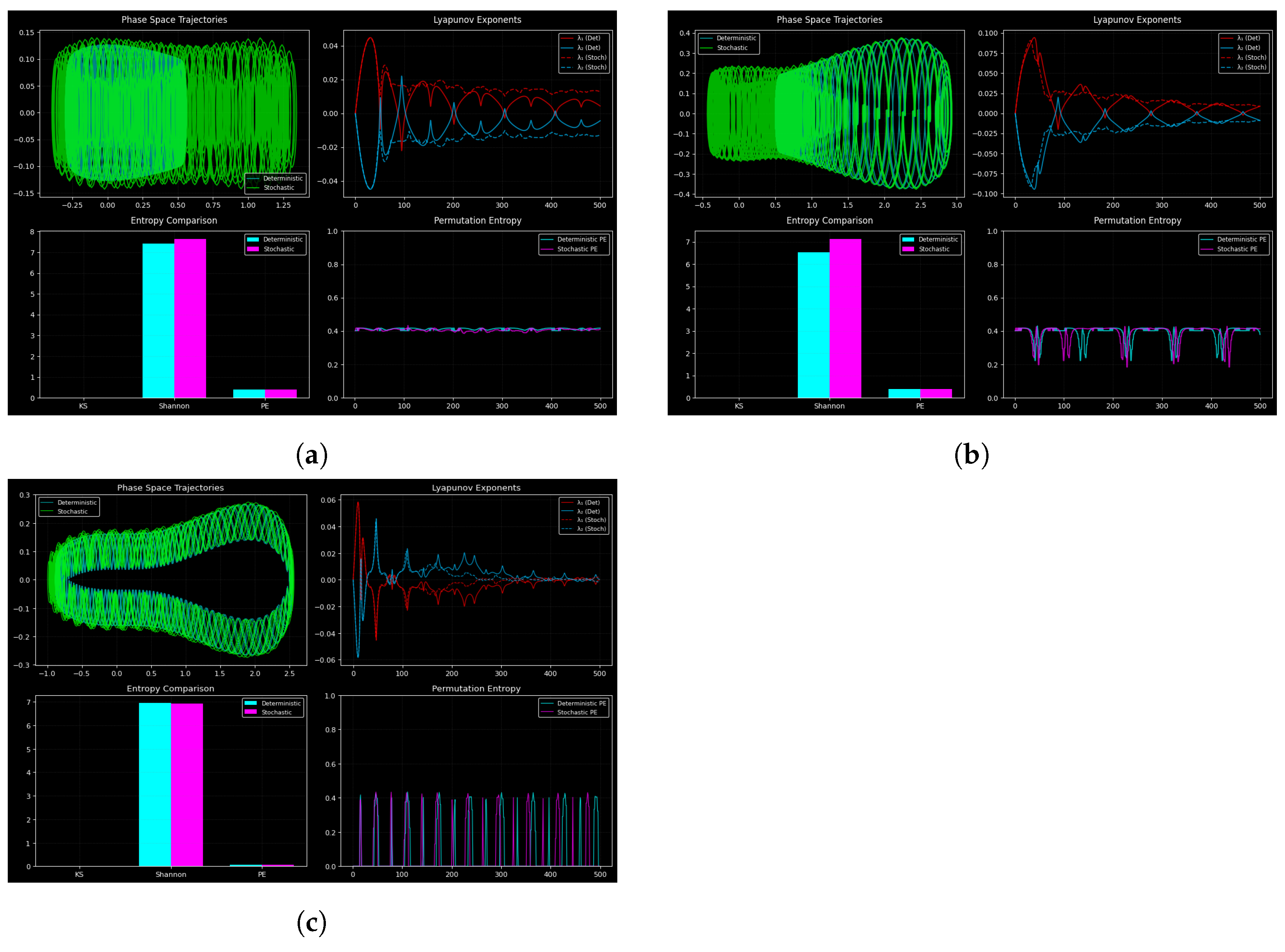

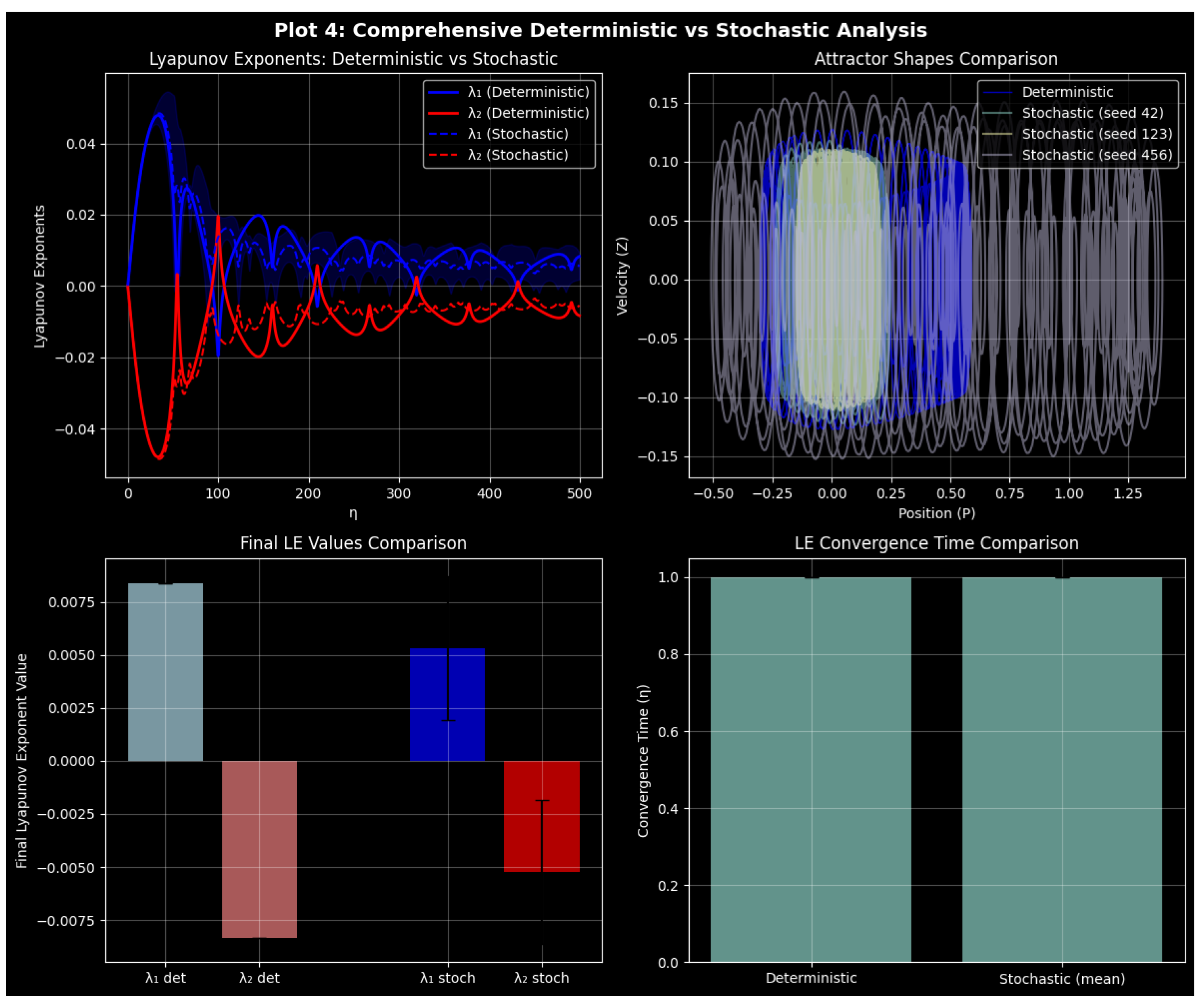

3.2. Attractor Dynamics and Order–Chaos Transition

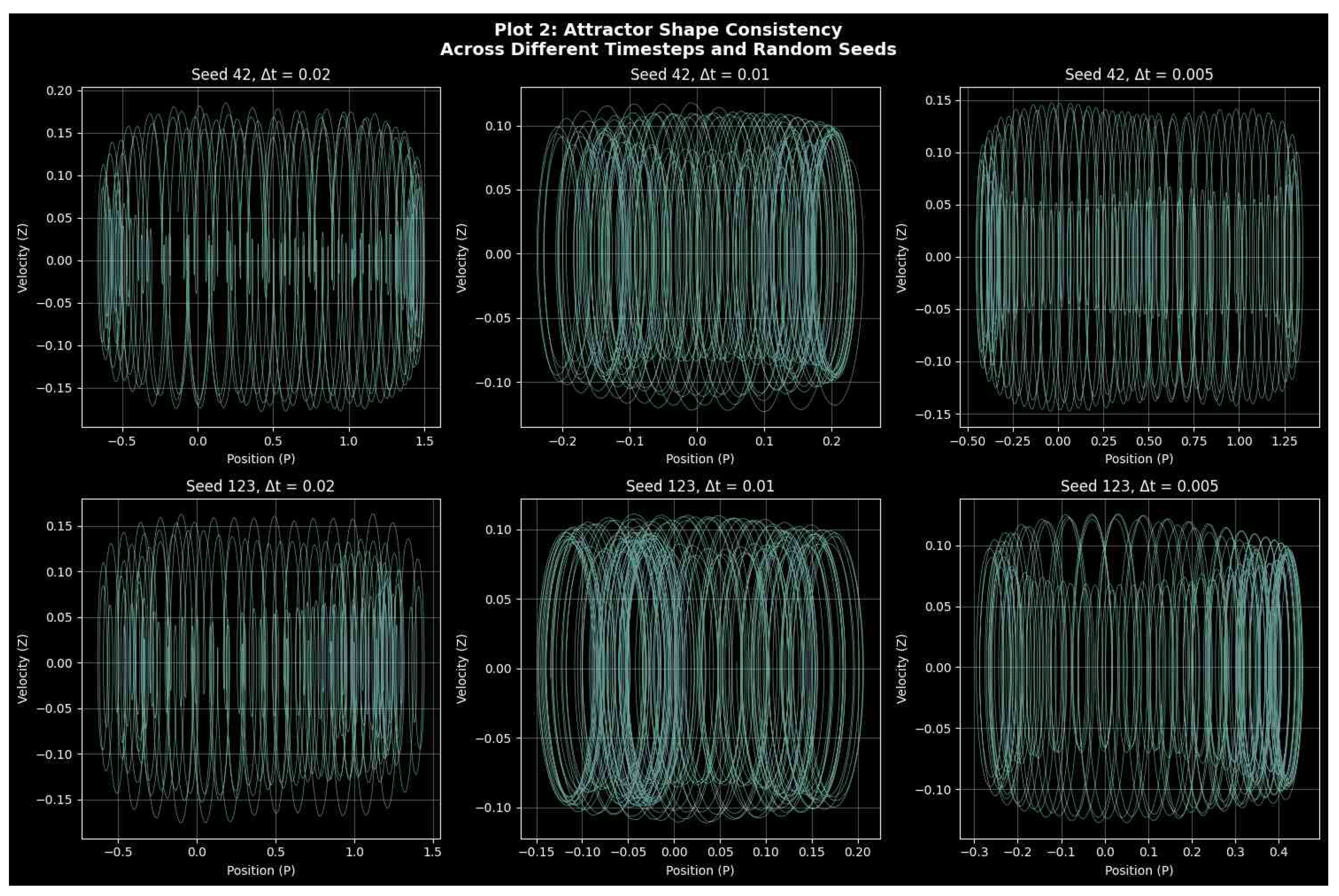

Attractor Geometry and Structural Consistency

3.3. Chaotic Features and Basin Stability

Basin Stability Analysis

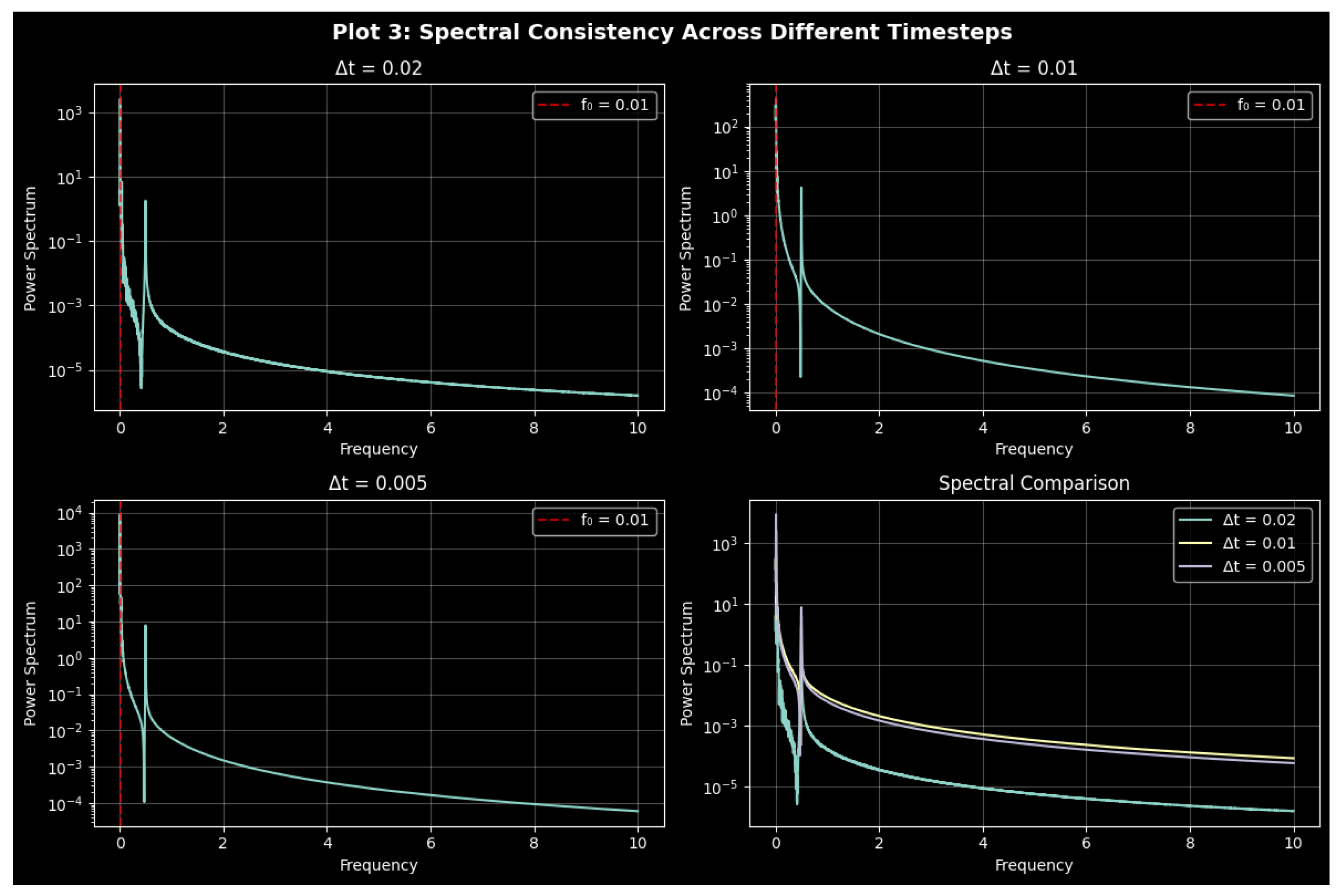

3.4. Analysis of Power Spectra

Quantitative Comparison of Noise Effects

3.5. Return Maps and Surrogate Data Validation

3.6. Chaotic Dynamics and Fractal Structure

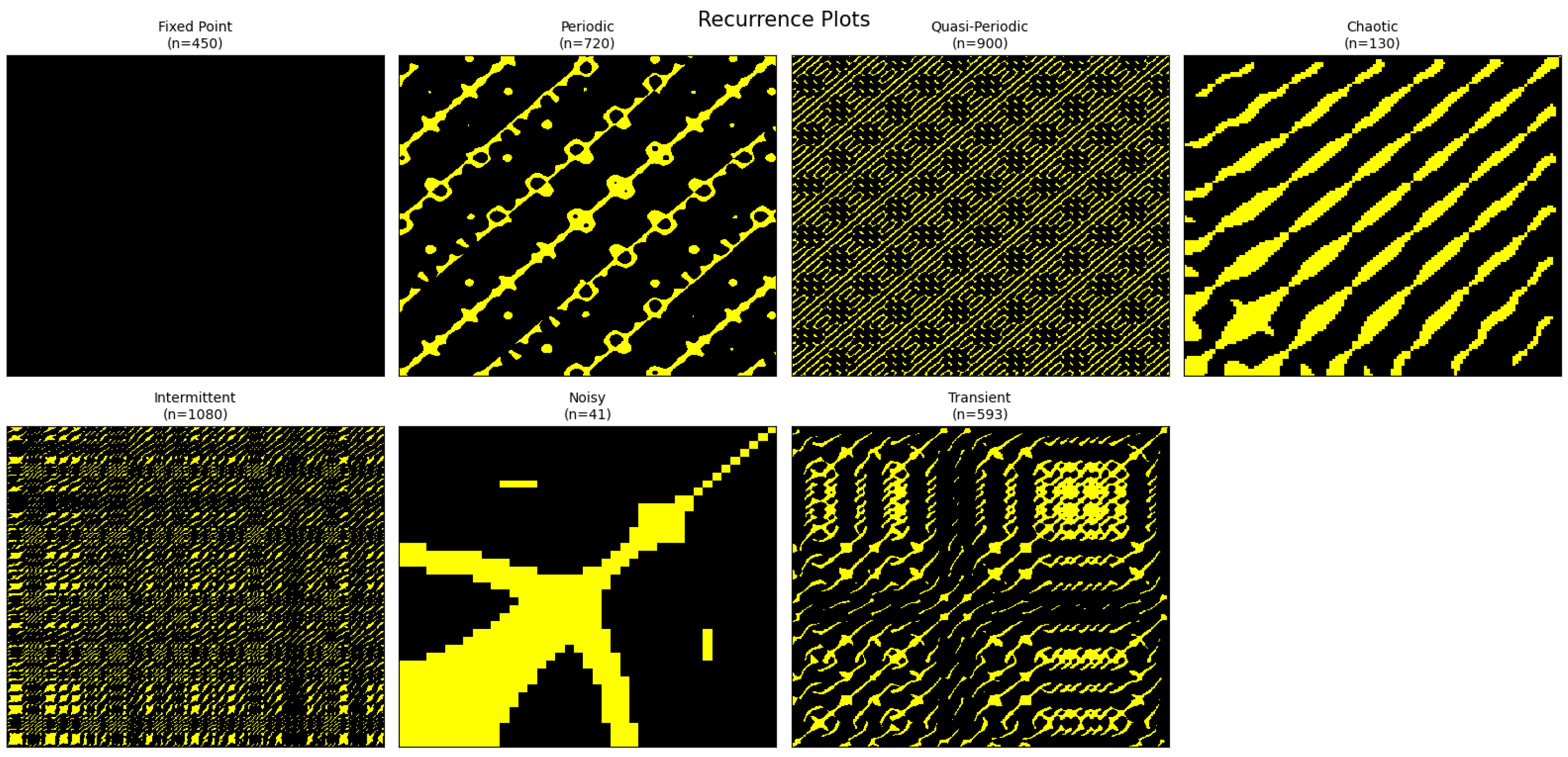

3.7. Dynamical Regimes via Recurrence Plots

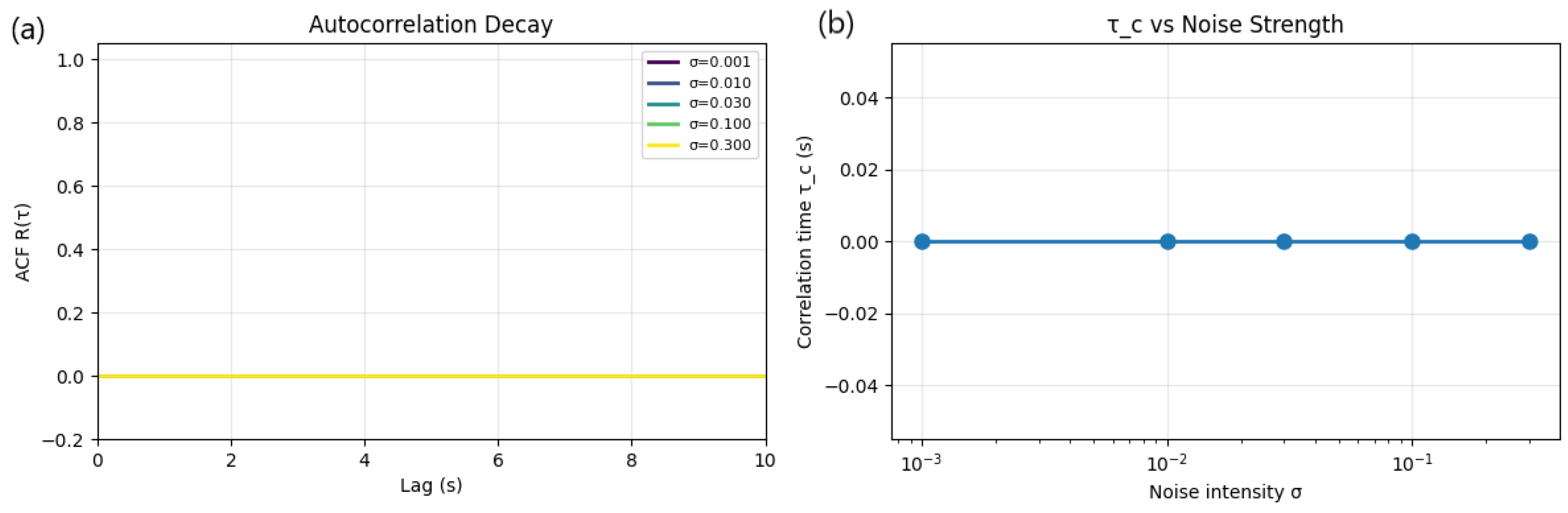

Autocorrelation and Memory Decay Analysis Under Stochastic Forcing

3.8. Noise-Induced Complexity: Stability and Chaos

3.9. Bifurcation Diagram and Lyapunov Spectrum Analysis

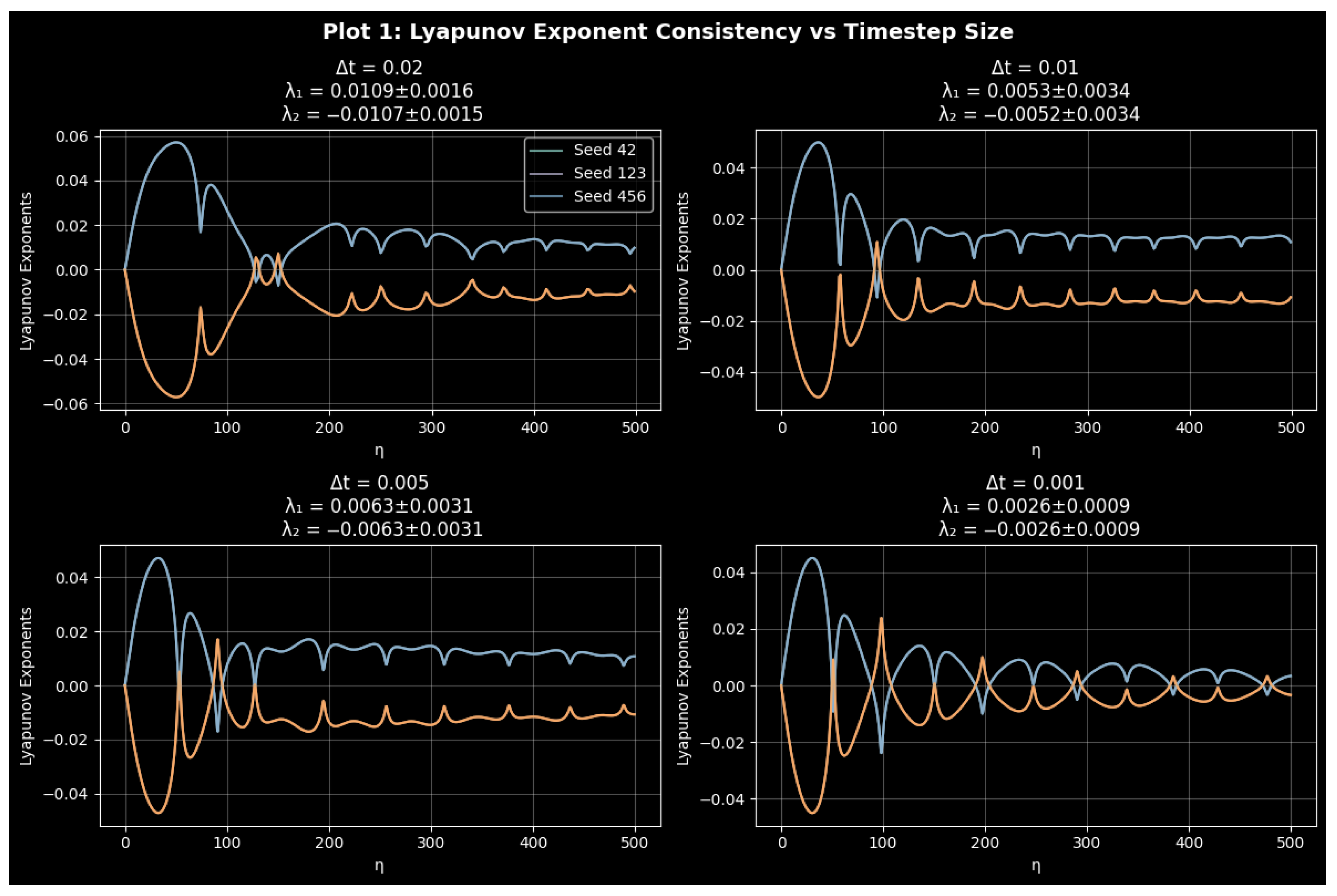

Numerical Consistency Analysis of the Stochastic Quartic Oscillator

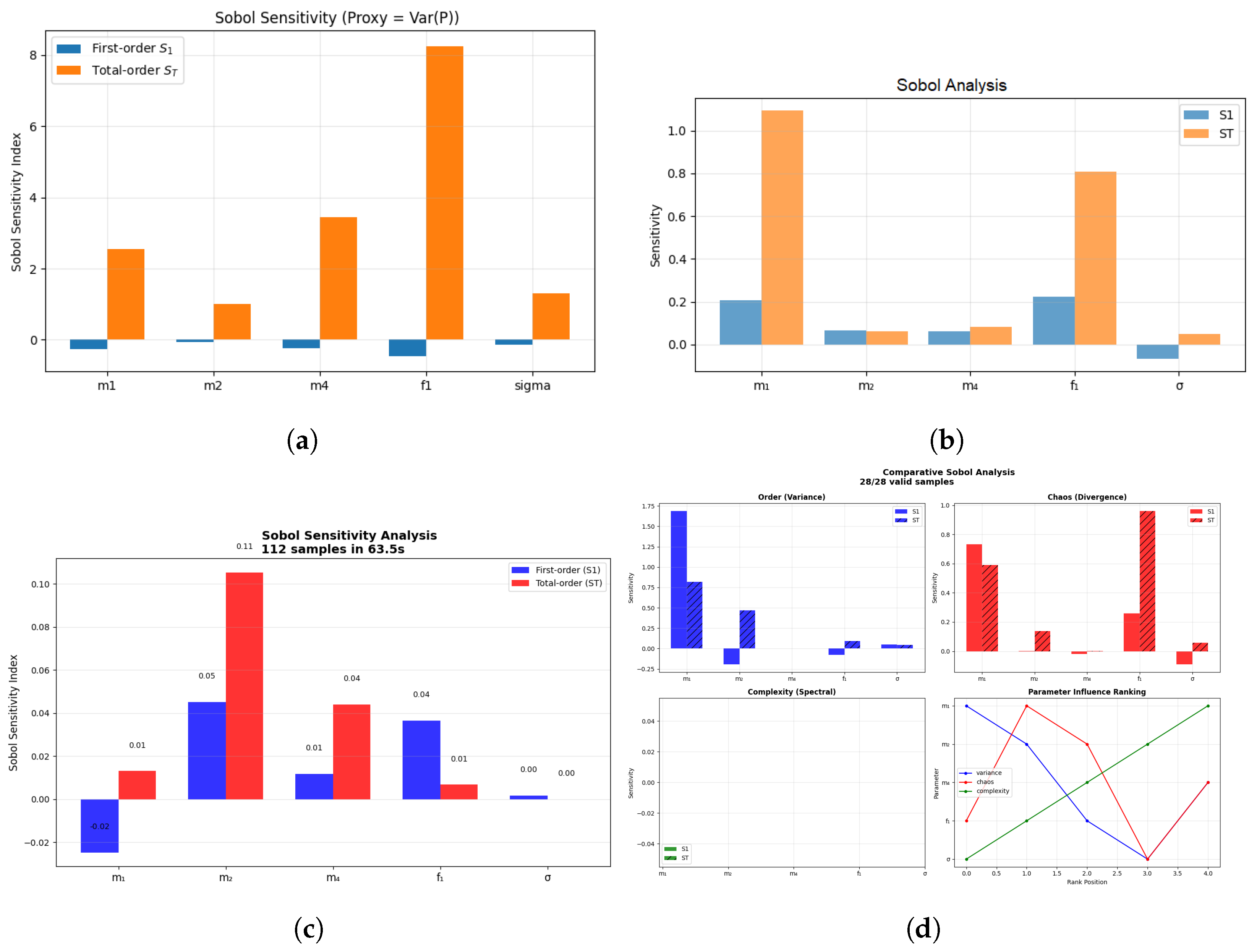

3.10. Variance-Based Sensitivity Analysis of the Stochastic SIdV Equation

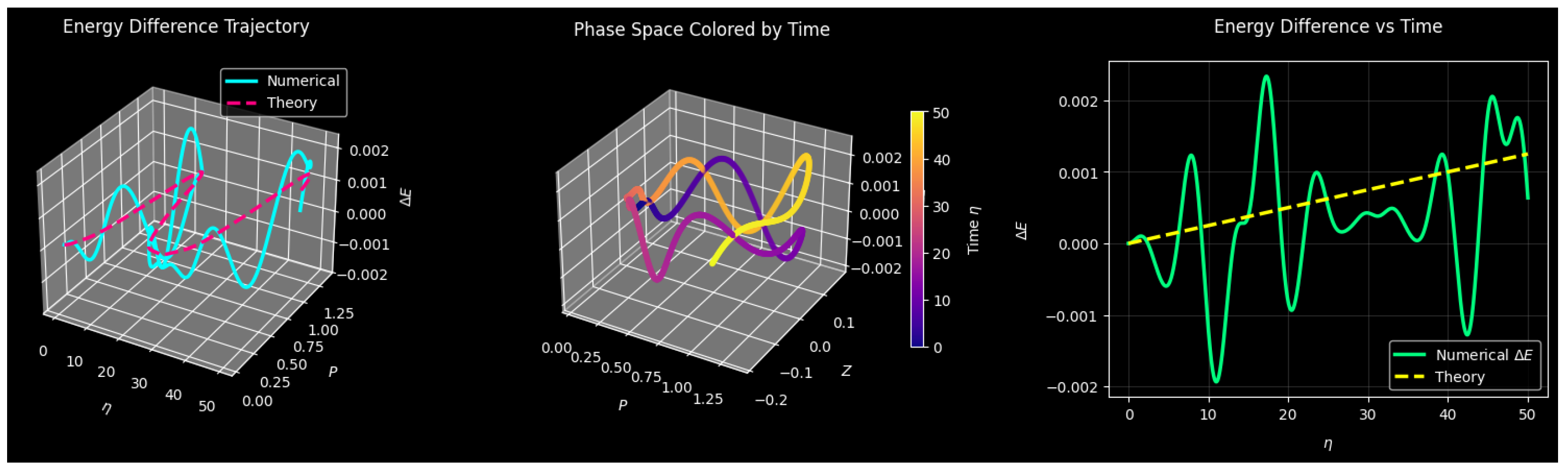

3.11. Analysis of the Perturbed Hamiltonian System

4. Comparative Context with Previous Studies

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Su, C.Y. Adaptive pseudoinverse control for constrained hysteretic nonlinear systems and its application on dielectric elastomer actuator. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2023, 28, 2142–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Feng, Q.; Yang, X.; He, J.R.; Li, B.Z. The octonion linear canonical transform: Properties and applications. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 192, 116039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Li, J. Improved energy-adaptive coupling for synchronization of neurons with nonlinear and memristive membranes. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 199, 116863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, T.; Hossain, I.; Ullah, M.S.; Hasan, M.M. Soliton, multistability, and chaotic dynamics of the higher-order nonlinear Schrödinger equation. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2025, 35, 043141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, I.; Boulaaras, S.M.; Althobaiti, S.; Althobaiti, A.; Rehman, H.U. Exploring soliton dynamics in the nonlinear Helmholtz equation: Bifurcation, chaotic behavior, multistability, and sensitivity analysis. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 16933–16954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, D.S. Exotic wave patterns in Riemann problem of the high-order Jaulent–Miodek equation: Whitham modulation theory. Stud. Appl. Math. 2022, 149, 588–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zeng, S. Discontinuous initial value and Whitham modulation for the generalized Gerdjikov-Ivanov equation. Wave Motion 2024, 127, 103276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Liu, Y. Hierarchical structure and N-soliton solutions of the generalized Gerdjikov–Ivanov equation via Riemann–Hilbert problem. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 12021–12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, M.Z.; Yasin, M.W.; Ahmed, N.; Ali, S.M.; Ali, M. Dynamical analysis and optical soliton wave profiles to GRIN multimode optical fiber under the effect of noise. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 20183–20198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayed, E.M.; Shohib, R.M.; Alngar, M.E.; Biswas, A.; Moraru, L.; Khan, S.; Yıldırım, Y.; Alshehri, H.M.; Belic, M.R. Dispersive optical solitons with Schrödinger–Hirota model having multiplicative white noise via Itô Calculus. Phys. Lett. A 2022, 445, 128268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Ibrahim, T.F.; Birkea, F.M.; Al-Sinan, B.R.; Alotaibi, A.M. Optical solitons for the Kudryashov–Sinelshchikov equation by two analytic approaches. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, K.; Alizadeh, F.; Hinçal, E.; Ilie, M.; Osman, M.S. Bilinear Bäcklund transformation, Lax pair, Painlevé integrability, and different wave structures of a 3D generalized KdV equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 18397–18411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzaleq, L.; Manoranjan, V.; Alzalg, B. Exact traveling waves of a generalized scale-invariant analogue of the Korteweg–de Vries equation. Mathematics 2022, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Aldosary, S.F.; Khan, M.A. Stochastic solitons of a short-wave intermediate dispersive variable (SIdV) equation. AIMS Math. 2024, 9, 10717–10733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Peng, C.; Li, Z. Explicit solutions of the generalized Kudryashov’s equation with truncated M-fractional derivative. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Askar, F.M.; Mohammed, W.W.; Albalahi, A.M.; El-Morshedy, M. The Impact of the Wiener process on the analytical solutions of the stochastic (2 + 1)-dimensional breaking soliton equation by using tanh–coth method. Mathematics 2022, 10, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, W.W.; Cesarano, C. The soliton solutions for the (4 + 1)-dimensional stochastic Fokas equation. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2023, 46, 7589–7597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Kai, Y. Wave structures, modulation instability analysis and chaotic behaviors to Kudryashov’s equation with third-order dispersion. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 10355–10371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiler, J.; Eubank, S.; Longtin, A.; Galdrikian, B.; Farmer, J.D. Testing for nonlinearity in time series: The method of surrogate data. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1992, 58, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letellier, C.; Rossler, O.E. Rossler attractor. Scholarpedia 2006, 1, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, K.; Kudra, G.; Skurativskyi, S.; Wasilewski, G.; Awrejcewicz, J. Modeling and dynamics analysis of a forced two-degree-of-freedom mechanical oscillator with magnetic springs. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 148, 107138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, J.; Farmer, J.; Packard, N.; Shaw, R. Chaos. Sci. Am. 1986, 225, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feudel, U. Complex dynamics in multistable systems. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2008, 18, 1607–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos: With Applications to Physics, Biology, Chemistry, and Engineering; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pyragas, K. Continuous control of chaos by self-controlling feedback. Phys. Lett. A 1992, 170, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.C.; Tél, T. Transient Chaos: Complex Dynamics on Finite Time Scales; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 173. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, B.; Garcıa-Ojalvo, J.; Neiman, A.; Schimansky-Geier, L. Effects of noise in excitable systems. Phys. Rep. 2004, 392, 321–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, R.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, J.; Du, S. Reliability estimation method based on nonlinear Tweedie exponential dispersion process and evidential reasoning rule. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 206, 111205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodba, S.; Perc, M.; Marhl, M. Detecting chaos from a time series. Eur. J. Phys. 2004, 26, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datseris, G.; Parlitz, U. Nonlinear Dynamics: A Concise Introduction Interlaced with Code; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Marwan, N.; Romano, M.C.; Thiel, M.; Kurths, J. Recurrence plots for the analysis of complex systems. Phys. Rep. 2007, 438, 237–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, C.L., Jr.; Zbilut, J.P. Recurrence quantification analysis of nonlinear dynamical systems. Tutor. Contemp. Nonlinear Methods Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 26–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kantz, H.; Schreiber, T. Nonlinear Time Series Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Menck, P.J.; Heitzig, J.; Marwan, N.; Kurths, J. How basin stability complements the linear-stability paradigm. Nat. Phys. 2013, 9, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccaletti, S.; Kurths, J.; Osipov, G.; Valladares, D.L.; Zhou, C.S. The synchronization of chaotic systems. Phys. Rep. 2002, 366, 1–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, M.; Romano, M.C.; Kurths, J.; Rolfs, M.; Kliegl, R. Generating surrogates from recurrences. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2008, 366, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, L.; Knothe, A.; Hentschel, M. Steering internal and outgoing electron dynamics in bilayer graphene cavities by cavity design. New J. Phys. 2024, 26, 103045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Kai, Y.; Zheng, B. Study of a generalized stochastic scale-invariant analogue of the Korteweg-de Vries equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 13665–13679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, G.P. Fiber-Optic Communication Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Remoissenet, M. Waves Called Solitons: Concepts and Experiments; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Waezizadeh, T.; Mehrpooya, A.; Rezaeizadeh, M.; Yarahmadian, S. Mathematical models for the effects of hypertension and stress on kidney and their uncertainty. Math. Biosci. 2018, 305, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouba, N.T.; Xu, H.; Alngar, M.E.; Shohib, R.M.; Mahmoud, H.A.; Zhu, X. Soliton solutions and stability analysis of the stochastic nonlinear reaction-diffusion equation with multiplicative white noise in soliton dynamics and optical physics. AIMS Math. 2025, 10, 1859–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, G. Chaotic Business Cycles within a Kaldor-Kalecki Framework. In Nonlinear Dynamical Systems with Self-Excited and Hidden Attractors; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Aminian, K. Nonlinear Analysis of Physiological Time Series. In Advanced Biosignal Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann, J.P.; Kamphorst, S.O.; Ruelle, D. Recurrence Plots of Dynamical Systems. In Turbulence, Strange Attractors and Chaos; World Scientific: Singapore, 1995; pp. 441–445. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, E. Chaos in Dynamical Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bandt, C.; Pompe, B. Permutation entropy: A natural complexity measure for time series. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 174102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.; Swift, J.B.; Swinney, H.L.; Vastano, J.A. Determining Lyapunov exponents from a time series. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 1985, 16, 285–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanic, M.; Jasiukiewicz, C.; Toklikishvili, Z.; Jandieri, V.; Trybus, M.; Jartych, E.; Mishra, S.K.; Chotorlishvili, L. Entanglement properties of photon-magnon crystal from nonlinear perspective. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2025, 476, 134699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanic, M.; Toklikishvili, Z.; Mishra, S.K.; Trybus, M.; Chotorlishvili, L. Magnetoelectric fractals, Magnetoelectric parametric resonance and Hopf bifurcation. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2024, 467, 134257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Figure | Parameters | Step Size | Time Span |

|---|---|---|---|

| Figure 9 | |||

| Figure 10 | |||

| Figure 11 |

| Aspect | White Noise | Brownian Noise | Colored Noise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| Power Spectrum | Smooth decay, low variability | High low-frequency power, high variability | Clean decay, moderate variability |

| Peak Frequency | Sharp and centered | Bimodal, unstable | Sharp and centered |

| Oscillations | Robust and preserved | Often disrupted | Preserved with mild dispersion |

| Stability | Stable, oscillations persist | Unstable, drift and incoherence | Partially stable, moderate variability |

| Metric | Original | Surrogates (Mean ± std) |

|---|---|---|

| Correlation dimension | 2.34 | 1.02 ± 0.15 |

| Recurrence rate | 0.41 | 0.18 ± 0.03 |

| >1000 | 142 ± 28 |

| Plot | Model Complexity | Key Parameters | Physical Role | Computational Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | Full nonlinear + stochastic | , | Chaos resonance | Balanced realism |

| (b) | Linear simplified | Stability amplitude | Maximum speed | |

| (c) | Nonlinear truncated | , , | Nonlinear amplification | Fast with realism |

| (d) | Multi-metric stochastic | , , , | Order–chaos transitions | Multi-observable insight |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wali, S.; Munawar, M.; Abdelkader, A.; Jhangeer, A.; Imran, M. Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics of the Intermediate Dispersive Velocity Equation with Soliton Stability and Chaos. Entropy 2025, 27, 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111176

Wali S, Munawar M, Abdelkader A, Jhangeer A, Imran M. Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics of the Intermediate Dispersive Velocity Equation with Soliton Stability and Chaos. Entropy. 2025; 27(11):1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111176

Chicago/Turabian StyleWali, Samad, Maham Munawar, Atef Abdelkader, Adil Jhangeer, and Mudassar Imran. 2025. "Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics of the Intermediate Dispersive Velocity Equation with Soliton Stability and Chaos" Entropy 27, no. 11: 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111176

APA StyleWali, S., Munawar, M., Abdelkader, A., Jhangeer, A., & Imran, M. (2025). Nonlinear Stochastic Dynamics of the Intermediate Dispersive Velocity Equation with Soliton Stability and Chaos. Entropy, 27(11), 1176. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111176