Research on Image Encryption with Multi-Level Keys Based on a Six-Dimensional Memristive Chaotic System

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Basic Theory

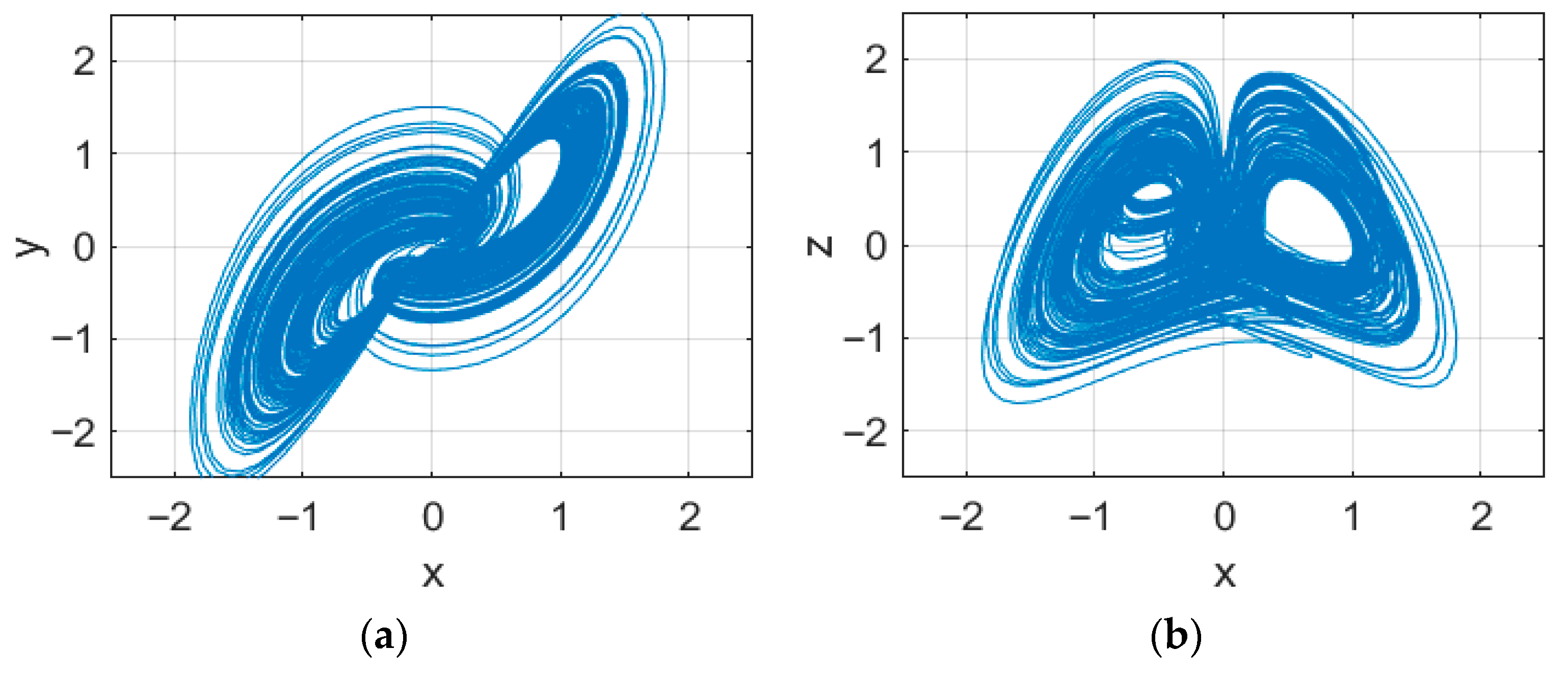

2.1. Six-Dimensional Memristive Chaotic System

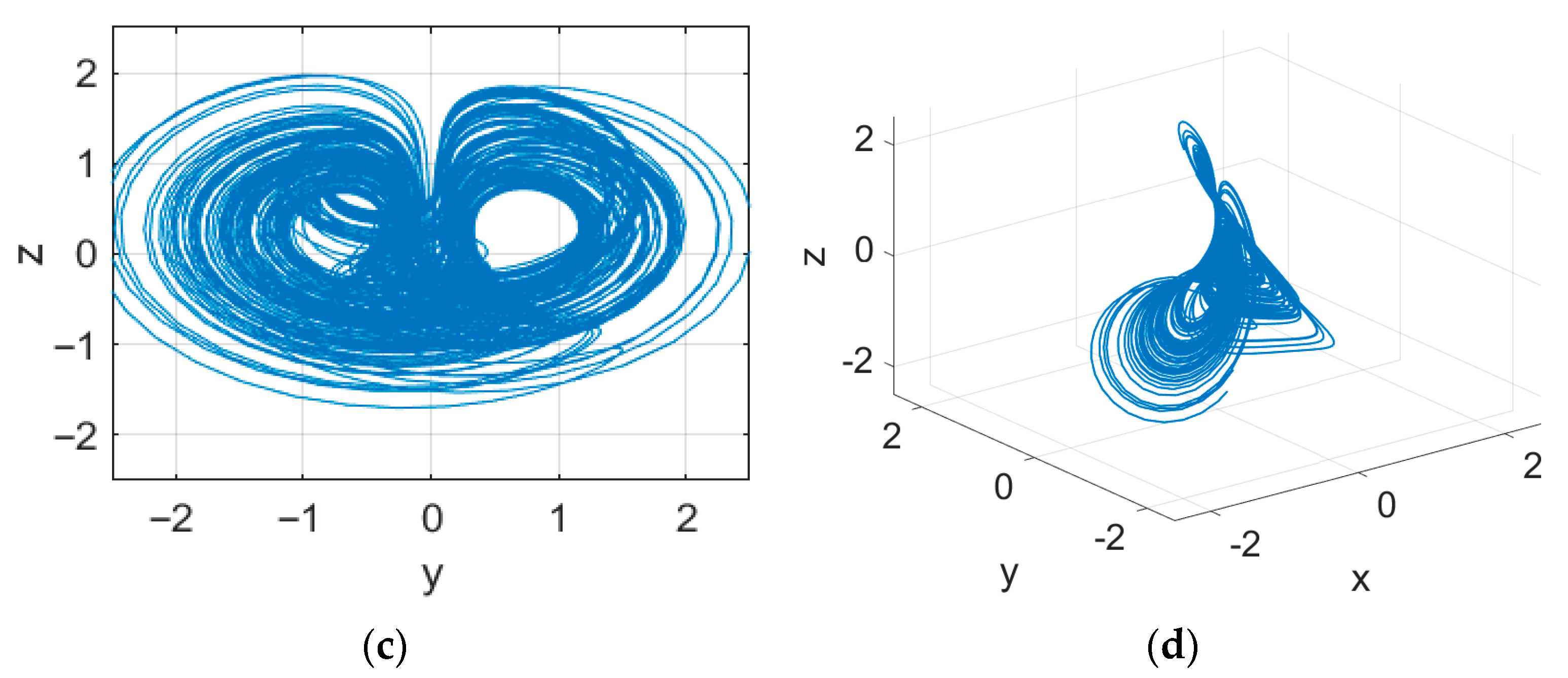

2.2. Zigzag Scrambling

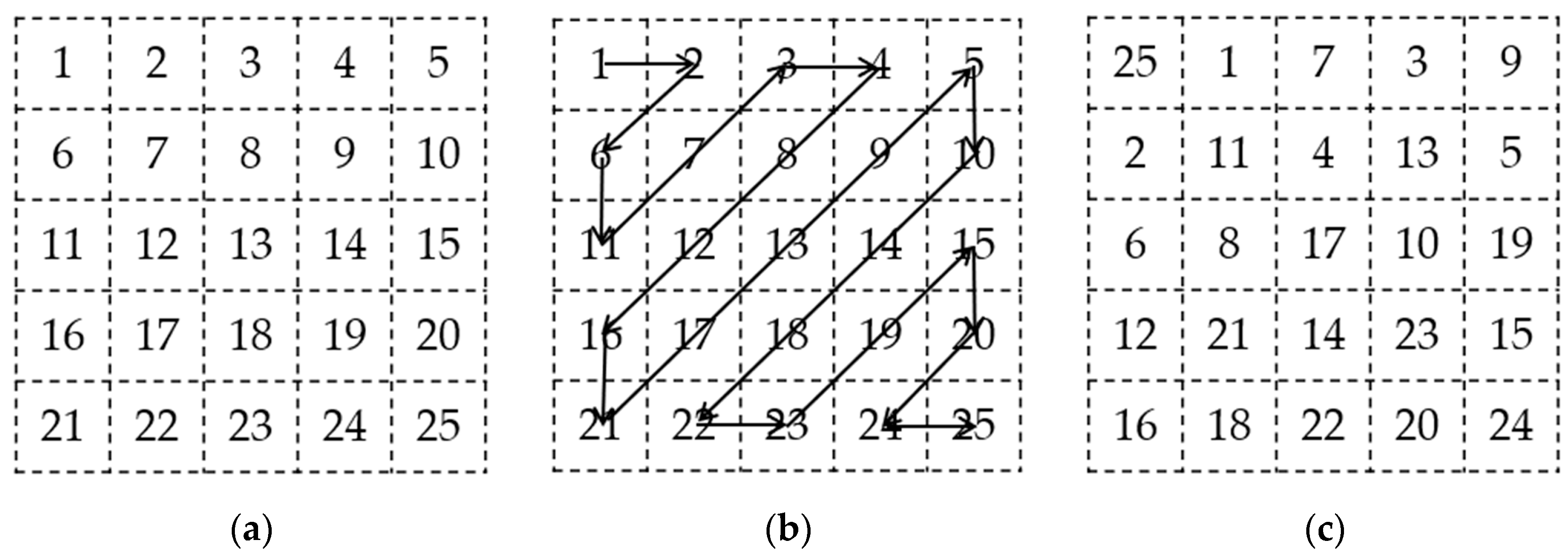

2.3. Chaotic Index Scrambling

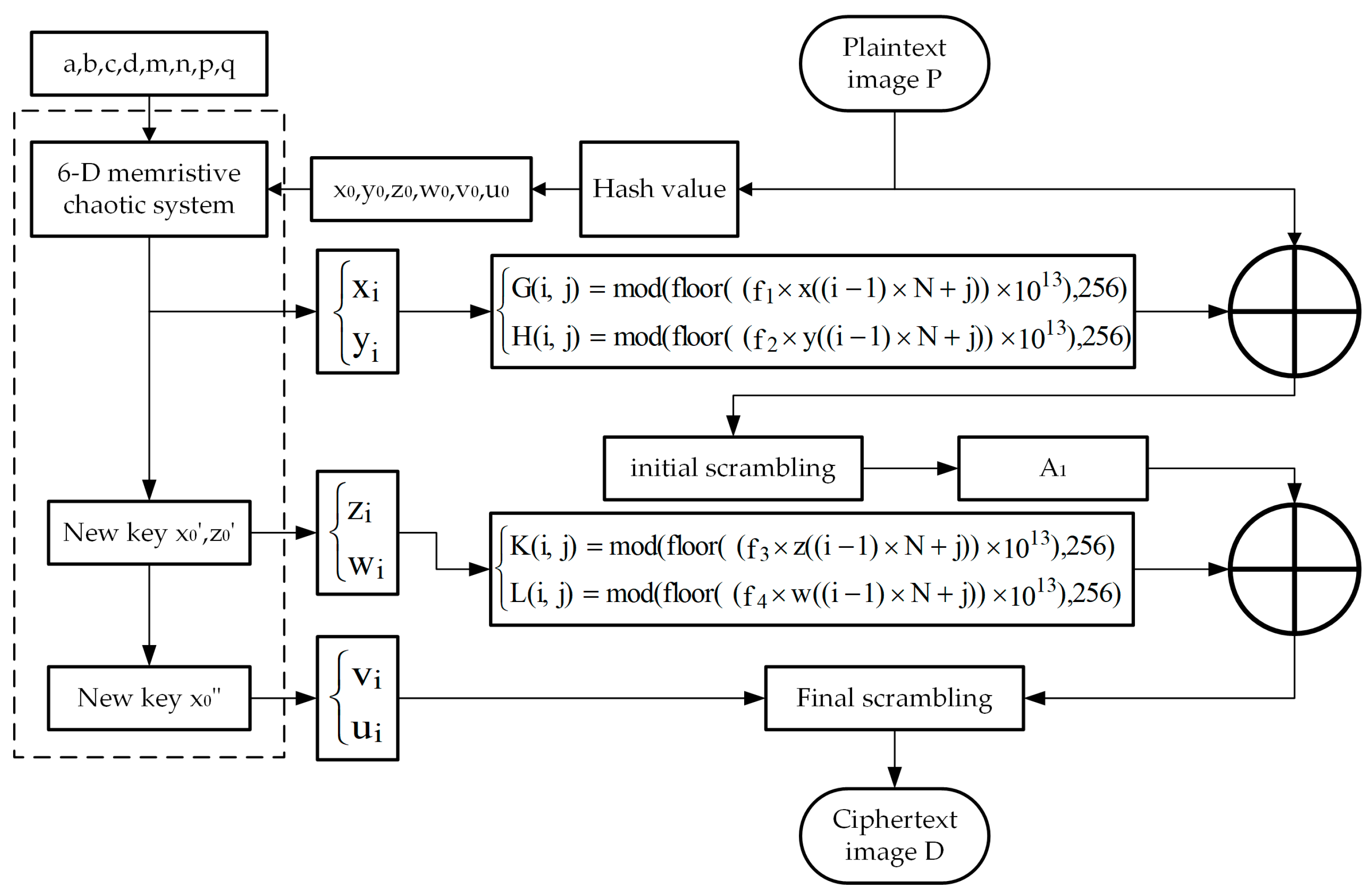

3. Encryption Algorithm

3.1. Image Encryption Algorithm Design

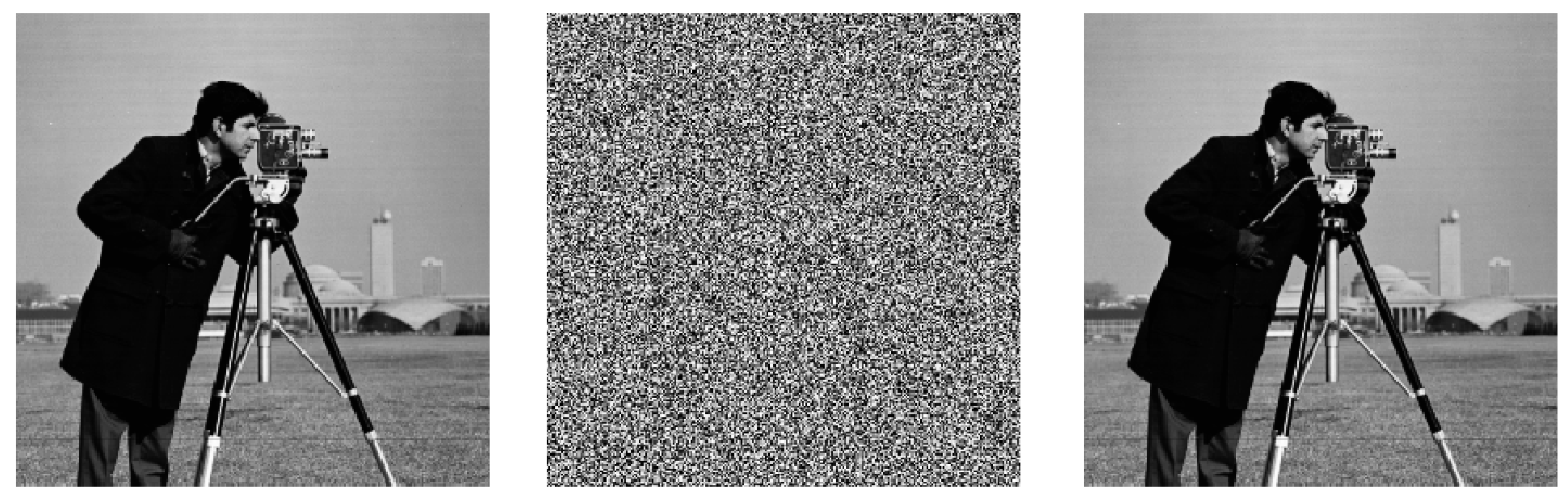

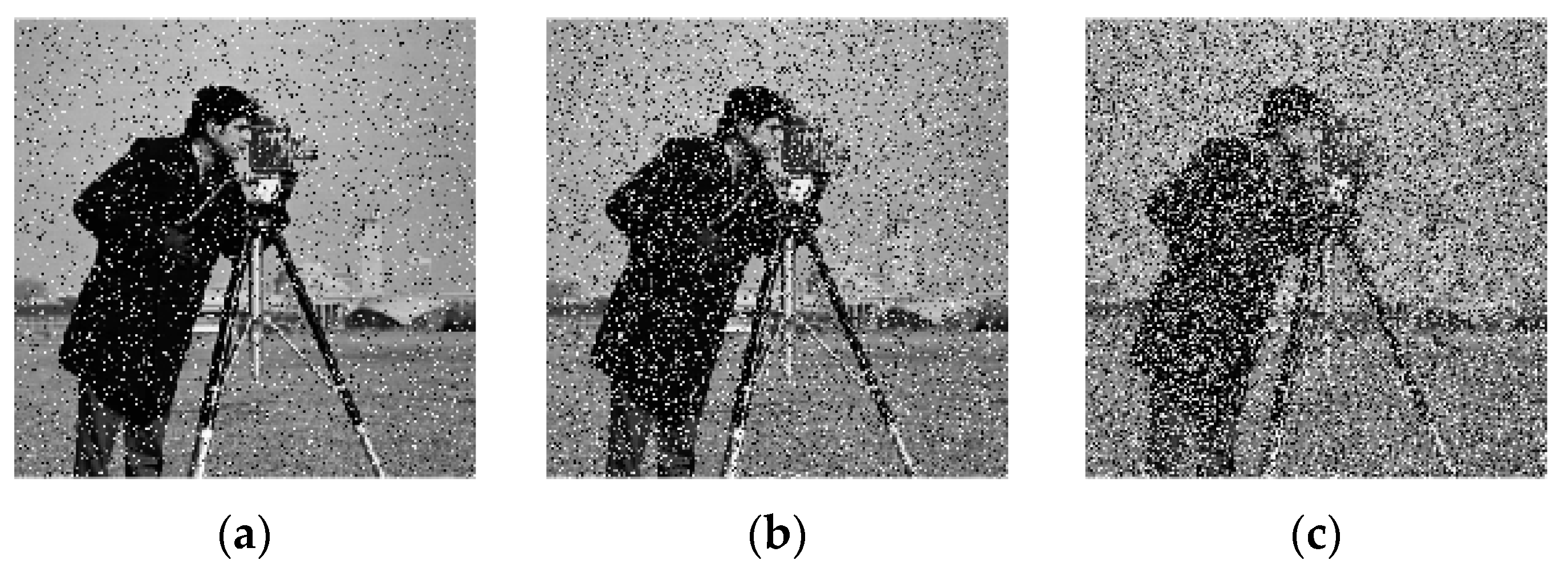

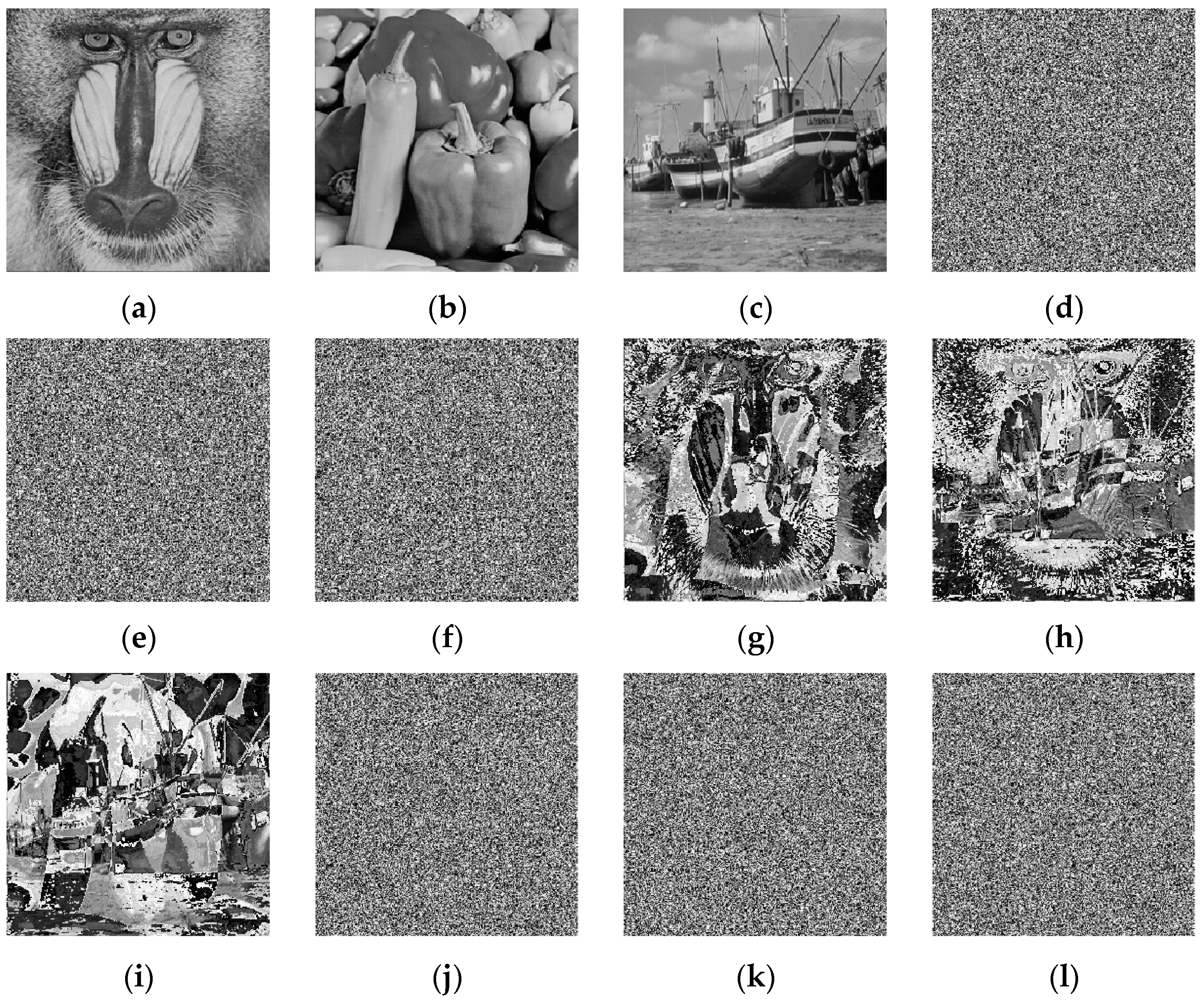

3.2. Experimental Results of Encryption Algorithm

4. Security Analysis

4.1. Key Space Analysis

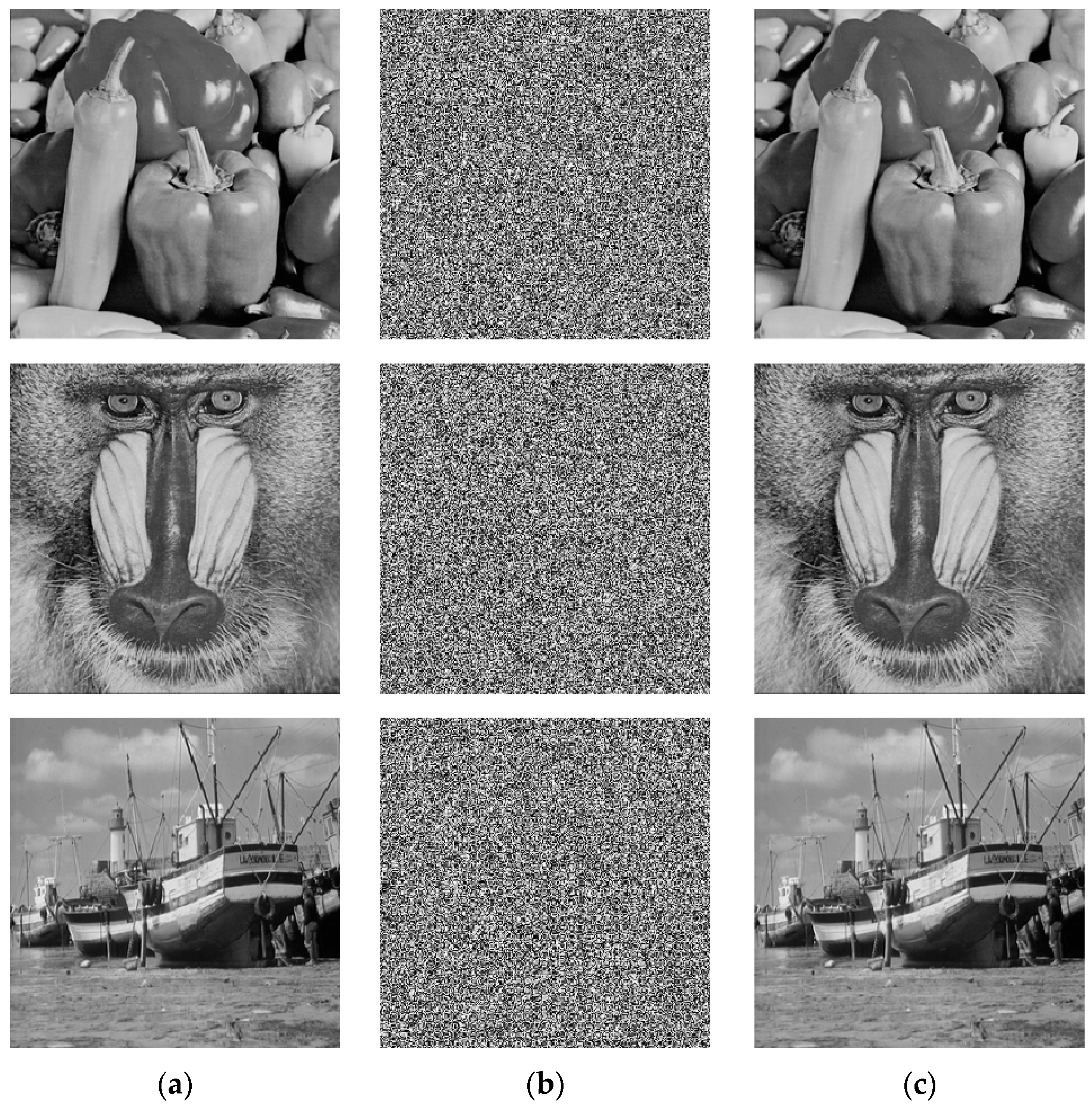

4.2. Key Sensitivity Analysis

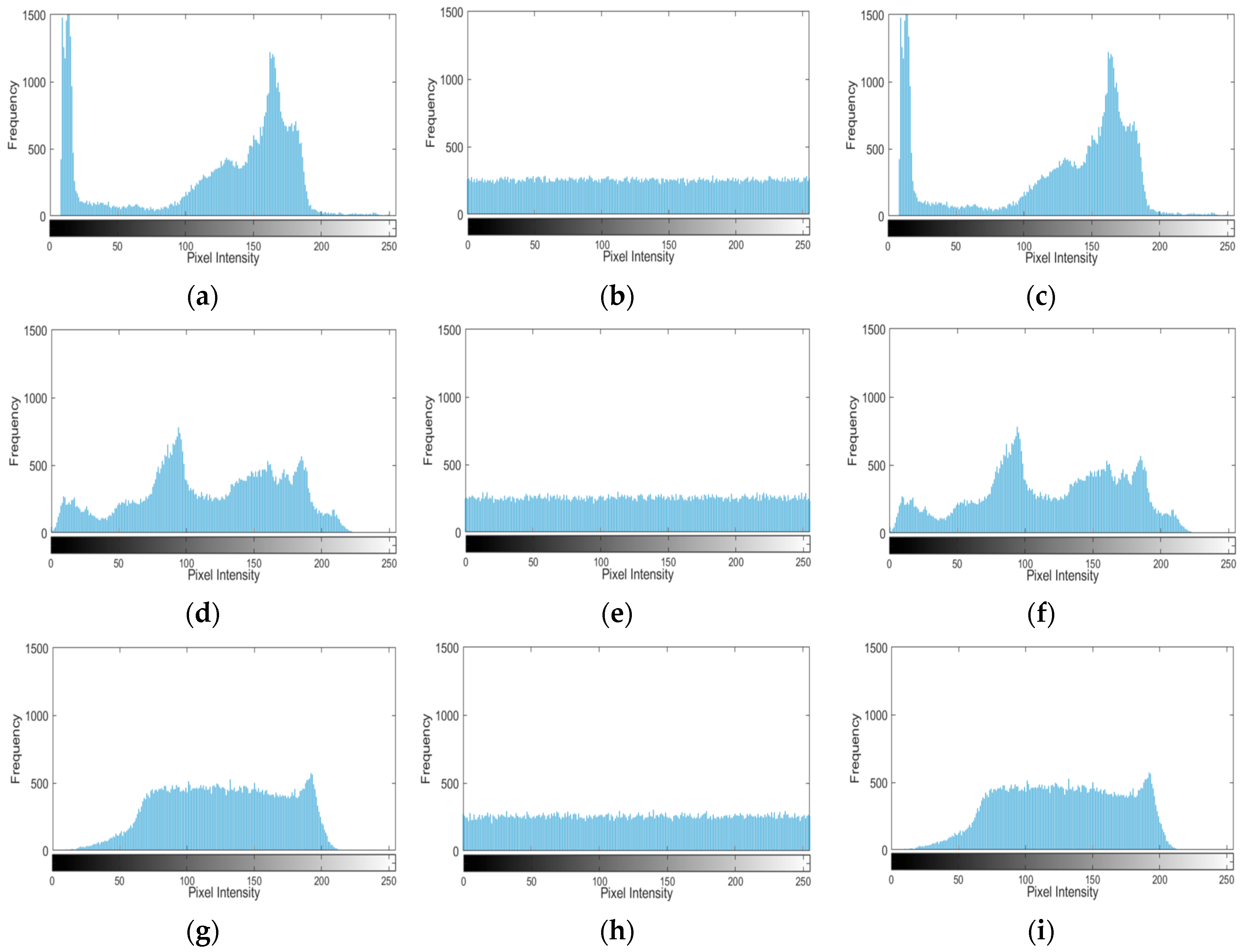

4.3. Histogram Analysis

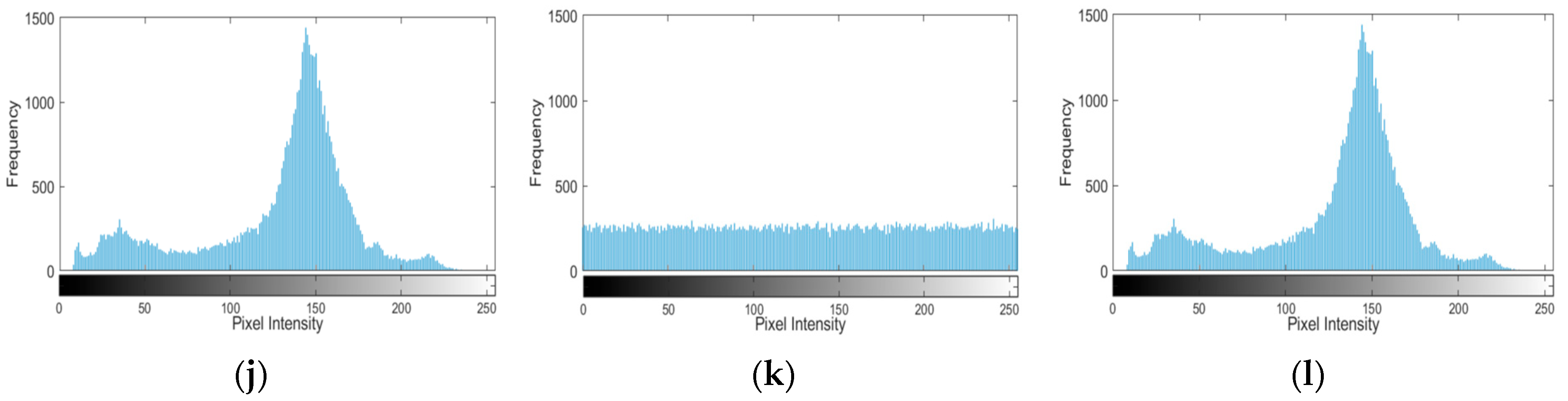

4.4. Correlation Analysis

4.5. Information Entropy Analysis

4.6. Differential Attack

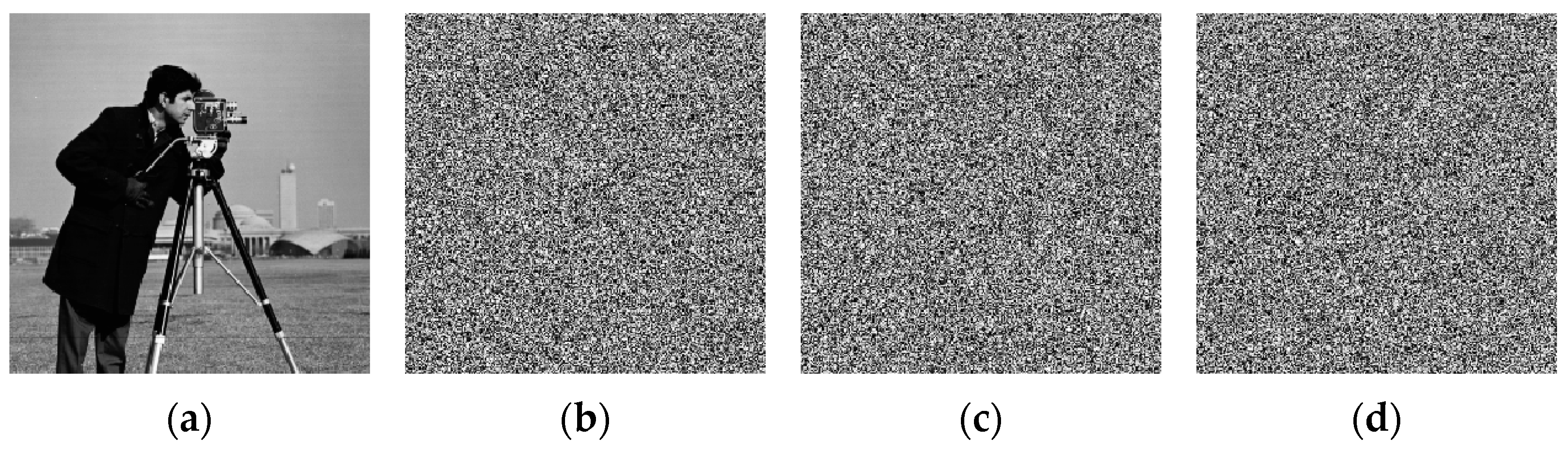

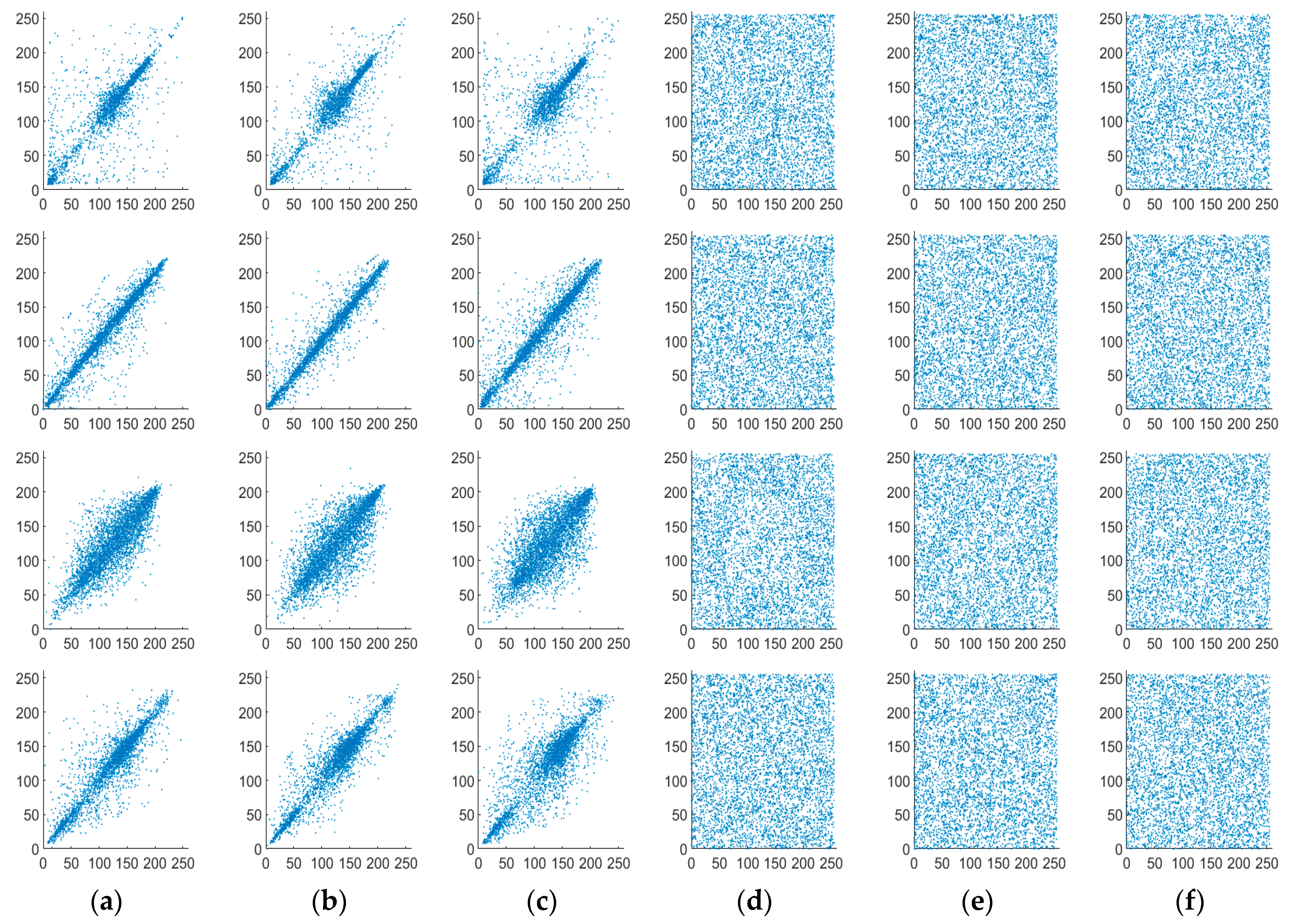

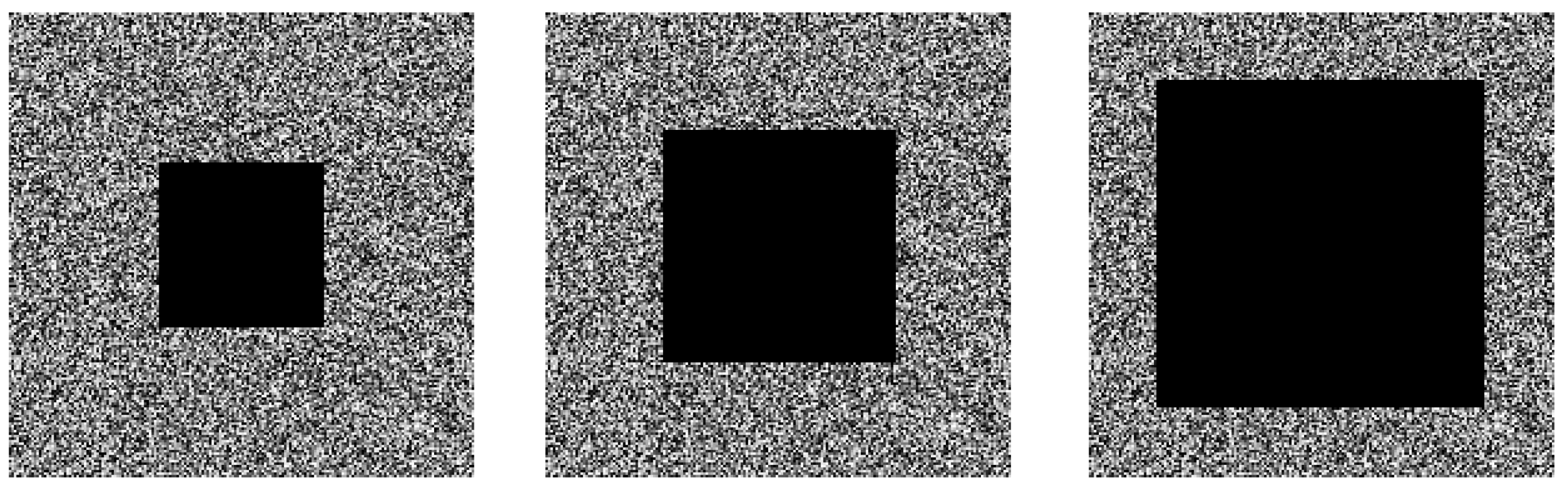

4.7. Anti-Noise Capability Analysis

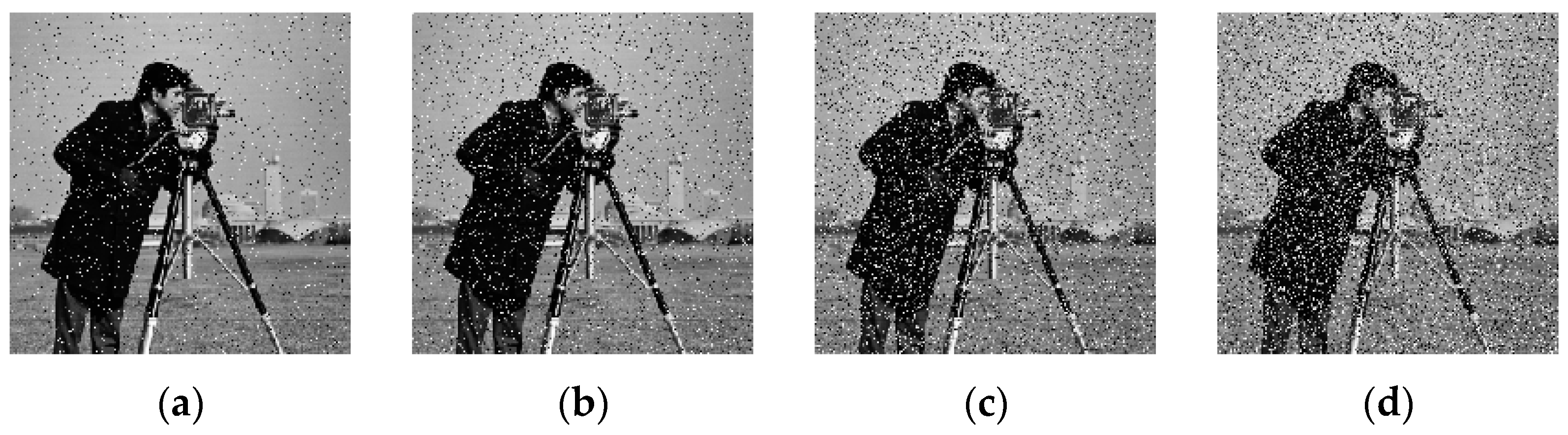

4.8. Cropping Attack Analysis

4.9. Algorithm Efficiency Analysis

4.10. Chosen-Plaintext Attack Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, C. An image encryption algorithm based on tabu search and hyperchaos. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2024, 34, 2450170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-den, B.M.; Raslan, W.A.; Abdullah, A.A. Even symmetric chaotic and skewed maps as a technique in video encryption. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2023, 2023, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talhaoui, M.Z.; Wang, X.; Talhaoui, A. A new one-dimensional chaotic map and its application in a novel permutation-less image encryption scheme. Vis. Comput. 2021, 37, 1757–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.C. Digital image encryption technology and its security analysis. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. 2020, 18, 104–105. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Li, G. Dynamic cat transformation and chaotic mapping image encryption algorithm. Comput. Eng. Des. 2020, 41, 2381–2387. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Liu, K.; Huang, Q.; Li, Q.; Huang, L. A plaintext-related and ciphertext feedback mechanism for medical image encryption based on a new one-dimensional chaotic system. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 125220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, A.; Ahmed, F. Image Encryption Using Dynamic S-Box Substitution in the Wavelet Domain. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2020, 115, 2243–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, M.; Fan, H.; An, K.; Liu, G. A novel plaintext-related chaotic image encryption scheme with no additional plaintext information. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 158, 111989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhao, K.; Cai, X.; Li, D.; Wang, Z. An image encryption method based on logistic chaotic mapping and DNA coding. In Proceedings of the MIPPR 2019: Remote Sensing Image Processing, Geographic Information Systems, and Other Applications, Wuhan, China, 2–3 November 2019; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; Volume 11432, pp. 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Du, J.; Fu, C.; Song, W. Image Encryption Algorithm Combining Chaotic Image Encryption and Convolutional Neural Network. Electronics 2023, 12, 3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrich, J. Symmetric ciphers based on two-dimensional chaotic maps. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 1998, 8, 1259–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X. Image encryption algorithm based on 2D hyperchaotic map. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 142, 107252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ren, Q.; Jiang, D. An adjustable visual image cryptosystem based on 6D hyperchaotic system and compressive sensing. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 104, 4543–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkouider, K.; Bouden, T.; Yalcin, M.E.; Vaidyanathan, S. A new family of 5D, 6D, 7D and 8D hyperchaotic systems from the 4D hyperchaotic Vaidyanathan system, the dynamic analysis of the 8D hyperchaotic system with six positive Lyapunov exponents and an application to secure communication design. Int. J. Model. Identif. Control. 2020, 35, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yan, H.; Banerjee, S.; Mou, J. A fractional-order chaotic system with hidden attractor and self-excited attractor and its DSP implementation. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 145, 110791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Qian, S.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Shi, C.; Cai, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, C. A new 4D four-wing memristive hyperchaotic system: Dynamical analysis, electronic circuit design, shape synchronization and secure communication. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2020, 30, 2050147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Zhou, L. A novel 6D four-wing memristive hyperchaotic system: Generalized fixed-time synchronization and its application in secure image encryption. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 192, 115986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, M.; Chua, L.O. Memristor oscillators. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 2008, 18, 3183–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Z.; Nazarimehr, F.; Jafari, S. A novel memristive chaotic system without any equilibrium point. Integration 2021, 79, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Li, M.; Xu, J.Q.; Lei, J.W. Memristive chaotic system with symmetric multistability and its synchronization control. J. Green Sci. Technol. 2024, 26, 223–229+236. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, Y.; Bu, F.; Jahanshahi, H.; Wang, L. A chaos-based image encryption scheme using the hamming distance and dna sequence operation. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 911156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Long, G.; Jiang, D.; Chai, X.; Han, J. Optical image encryption algorithm based on a new four-dimensional memristive hyperchaotic system and compressed sensing. Chin. Phys. B 2023, 32, 114203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devipriya, M.; Brindha, M. Reconfigurable architecture for DNA diffusion technique-based medical image encryption. J. Circuits Syst. Comput. 2023, 32, 2350065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, P.; Khan, N. The large key space image encryption algorithm based on modulus synchronization between real and complex fractional-order dynamical systems. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 17801–17825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Kumar, V. A comprehensive review on image encryption techniques. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2020, 27, 15–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukur, A.A.; Neamah, A.A.; Pham, V.T.; Grassi, G. A novel chaotic system with one absolute term: Stability, ultimate boundedness, and image encryption. Heliyon 2025, 11, e37239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelli, A.; Youssef, W.E.H.; Khriji, L.; Machhout, M. Enhanced lightweight encryption algorithm based on chaotic systems. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 106006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Zhang, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; He, P. An Innovative Image Encryption Algorithm Based on the DNAS_box and Hyperchaos. Entropy 2025, 27, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussien, R.A.; Radhi, S.S.; Rashid, F.F.; Abdulla, E.N.; Abass, A. Design and performance analysis of secure optical communication system by implementing blowfish cipher algorithm. Results Opt. 2024, 16, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelli, A.; Youssef, W.E.H.; Kharroubi, F.; Khriji, L.; Machhout, M. A novel enhanced chaos based present lightweight cipher scheme. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 016004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Jie, J.; Liu, Z.; Dong, K. Chaotic Image Encryption System as a Proactive Scheme for Image Transmission in FSO High-Altitude Platform. Photonics 2025, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Su, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y. A new image encryption algorithm based on Latin square matrix. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 107, 1277–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afify, Y.M.; Sharkawy, N.H.; Gad, W.; Badr, N. A new dynamic DNA-coding model for gray-scale image encryption. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Wang, E.; Liu, J. Research on Image Encryption Based on Fractional Seed Chaos Generator and Fractal Theory. Fractal Fract. 2023, 7, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Zheng, X.; Gan, Z.; Chen, Y. Exploiting plaintext-related mechanism for secure color image encryption. Neural Comput. Applic. 2020, 32, 8065–8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, D. A chaotic based image encryption scheme using elliptic curve cryptography and genetic algorithm. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahraoui, Y.; Lazaar, S.; Amal, Y.; Nitaj, A. A Novel ECC-Based Method for Secure Image Encryption. Algorithms 2025, 18, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Song, W.; Di, J.; Zhang, X.; Zou, C. Image Encryption Method Based on Three-Dimensional Chaotic Systems and V-Shaped Scrambling. Entropy 2025, 27, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abodawood, M.A.; Amer, H.; Ata, M.M. Robust Image Encryption Framework Leveraging Multi-Chaotic Map Synergy for Advanced Data Security. Int. J. Telecommun. 2025, 5, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsandi, N.S.A.; Zebari, D.A.; Al-Zebari, A.; Ahmed, F.Y.; Mohammed, M.A.; Albahar, M.A.; Albahr, A.A. A Multi-Stream Scrambling and DNA Encoding Method Based Image Encryption. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2023, 47, 1321–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, W.; Dai, Y.; Li, L. Novel One-Dimensional Chaotic System and Its Application in Image Encryption. Complexity 2022, 2022, 1720842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Images | Image Size | Plain | Cipher | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameraman | 256 × 256 | 110,973.30 | 186.6875 | 99.8318% |

| Peppers | 31,988.95 | 268.0859 | 99.1619% | |

| Baboon | 42,256.09 | 255.5156 | 99.3953% | |

| Boat | 100,313.13 | 263.1250 | 99.7380% | |

| Cameraman | 512 × 512 | 420,990.80 | 235.6230 | 99.9440% |

| Peppers | 127,496.13 | 242.3477 | 99.8099% | |

| Baboon | 175,925.14 | 277.9355 | 99.8420% | |

| Boat | 406,895.03 | 263.2461 | 99.9353% |

| Images | Direction | Plaintext | Ciphertext | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameraman (256 × 256) | Horizontal | 0.9335 | −0.0044 | 99.5287% |

| Vertical | 0.9592 | −0.0031 | 99.6768% | |

| Diagonal | 0.9087 | 0.0060 | 99.3397% | |

| Peppers (256 × 256) | Horizontal | 0.9620 | −0.0036 | 99.6258% |

| Vertical | 0.9698 | 0.0048 | 99.5051% | |

| Diagonal | 0.9357 | −0.0033 | 99.6473% | |

| Baboon (256 × 256) | Horizontal | 0.8529 | 0.0045 | 99.4724% |

| Vertical | 0.8163 | −0.0001 | 99.9877% | |

| Diagonal | 0.7709 | 0.00001 | 99.9987% | |

| Boat (256 × 256) | Horizontal | 0.9171 | 0.0020 | 99.7819% |

| Vertical | 0.9391 | 0.0036 | 99.6167% | |

| Diagonal | 0.8708 | −0.0011 | 99.8737% | |

| Cameraman (512 × 512) | Horizontal | 0.9834 | −0.0002 | 99.9797% |

| Vertical | 0.9903 | −0.0020 | 99.7980% | |

| Diagonal | 0.9737 | 0.0011 | 99.8870% | |

| Baboon (512 × 512) | Horizontal | 0.9647 | −0.0003 | 99.9689% |

| Vertical | 0.9546 | 0.0004 | 99.9581% | |

| Diagonal | 0.9273 | −0.0035 | 99.6226% |

| Images | Algorithm | Plain | Cipher | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal | Vertical | Diagonal | Horizontal | Vertical | Diagonal | Average | ||

| Cameraman (512 × 512) | Ours | 0.9834 | 0.9903 | 0.9737 | −0.0002 | −0.0020 | 0.0011 | 0.0011 |

| [26] | 0.9834 | 0.9902 | 0.9737 | −0.0034 | 0.0009 | −0.0014 | 0.0019 | |

| [27] | 0.9829 | 0.9898 | 0.9730 | −0.0038 | −0.0051 | 0.0004 | 0.0031 | |

| Peppers (512 × 512) | Ours | 0.9904 | 0.9924 | 0.9823 | −0.0019 | 0.0013 | 0.0019 | 0.0017 |

| [26] | 0.9768 | 0.9792 | 0.9636 | −0.0004 | 0.0031 | −0.0031 | 0.0022 | |

| [27] | 0.9805 | 0.9829 | 0.9655 | −0.0046 | −0.0052 | 0.0001 | 0.0033 | |

| Baboon (512 × 512) | Ours | 0.9647 | 0.9546 | 0.9273 | −0.0003 | 0.0004 | −0.0035 | 0.0014 |

| [26] | 0.8665 | 0.7587 | 0.7262 | 0.0001 | −0.0001 | 0.0045 | 0.0016 | |

| [27] | 0.9317 | 0.9105 | 0.8650 | −0.0067 | −0.0058 | 0.0027 | 0.0051 | |

| Images | Image Size | Plaintext | Ciphertext |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cameraman | 256 × 256 | 7.0097 | 7.9979 |

| Peppers | 7.5797 | 7.9971 | |

| Baboon | 7.3715 | 7.9972 | |

| Cameraman | 512 × 512 | 7.0482 | 7.9994 |

| Peppers | 7.5808 | 7.9993 | |

| Baboon | 7.3468 | 7.9992 |

| Images | Image Size | Ref. [26] | Ref. [27] | Ref. [29] | Ref. [30] | Ref. [31] | Ref. [32] | Proposed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameraman | 256 × 256 | - | - | 7.9972 | 7.9968 | 7.9973 | 7.9976 | 7.9979 |

| Peppers | - | - | 7.9971 | 7.9971 | 7.9972 | - | 7.9971 | |

| Baboon | - | - | - | 7.9970 | 7.9970 | - | 7.9972 | |

| Cameraman | 512 × 512 | 7.9993 | 7.9988 | - | - | 7.9993 | 7.9993 | 7.9994 |

| Size | Parameter | Cameraman | Peppers | Baboon | Boat | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 256 × 256 | NPCR (%) | 99.6111 | 99.6083 | 99.6091 | 99.6104 | 99.6097 |

| UACI (%) | 33.4643 | 33.4580 | 33.4463 | 33.4840 | 33.4631 | |

| 512 × 512 | NPCR (%) | 99.6099 | 99.6114 | 99.6085 | 99.6091 | 99.6097 |

| UACI (%) | 33.4554 | 33.4601 | 33.4949 | 33.4354 | 33.4615 | |

| 256 × 256 | NPCR (%) | 99.6102 | 99.6152 | 99.6093 | 99.6134 | 99.6120 |

| UACI (%) | 33.4602 | 33.4616 | 33.4344 | 33.4780 | 33.4586 | |

| 512 × 512 | NPCR (%) | 99.6071 | 99.6096 | 99.6093 | 99.6117 | 99.6094 |

| UACI (%) | 33.4637 | 33.4880 | 33.4827 | 33.4239 | 33.4646 |

| Parameter | Proposed | Ref. [29] | Ref. [34] | Ref. [35] | Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPCR (%) | 99.6111 | 99.6078 | 99.64 | 99.6017 | 99.6094 |

| UACI (%) | 33.4643 | 33.5237 | 33.39 | 33.3855 | 33.4635 |

| Algorithm | Images | Size | Noise Intensity | PSNR (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | Cameraman | 256 × 256 | 0.05 | 21.3757 |

| 0.1 | 18.4846 | |||

| 0.2 | 15.3956 | |||

| 0.3 | 13.6608 | |||

| Baboon | 256 × 256 | 0.05 | 22.5374 | |

| 0.1 | 19.3729 | |||

| 0.2 | 16.3605 | |||

| 0.3 | 14.6581 | |||

| Boat | 256 × 256 | 0.05 | 22.4760 | |

| 0.1 | 19.2591 | |||

| 0.2 | 16.3732 | |||

| 0.3 | 14.6581 | |||

| Cameraman | 512 × 512 | 0.05 | 21.3916 | |

| 0.1 | 18.3453 | |||

| 0.2 | 15.3829 | |||

| 0.3 | 13.6757 | |||

| Baboon | 512 × 512 | 0.05 | 22.4504 | |

| 0.1 | 19.5186 | |||

| 0.2 | 16.4893 | |||

| 0.3 | 14.7262 | |||

| [29] | Cameraman | 256 × 256 | 0.05 | 17.8969 |

| 0.1 | 15.0925 | |||

| 0.2 | 12.5765 | |||

| 0.3 | 11.1662 | |||

| [31] | Cameraman | 512 × 512 | 0.005 | 37.64 |

| [37] | Cameraman | 512 × 512 | 0.1 | 18.2589 |

| Baboon | 0.1 | 19.2231 | ||

| [38] | Cameraman | 256 × 256 | 0.05 | 18.58 |

| Peppers | 256 × 256 | 0.05 | 19.14 | |

| Boat | 512 × 512 | 0.05 | 19.46 | |

| [39] | Boat | 256 × 256 | 0.05 | 22.3642 |

| 0.1 | 19.1878 |

| Algorithm | Images | Size | Ratio | PSNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ours | Cameraman | 256 × 256 | 1/8 | 17.5778 |

| 1/4 | 14.4552 | |||

| 1/2 | 11.4224 | |||

| Peppers | 256 × 256 | 1/8 | 17.9909 | |

| 1/4 | 14.9162 | |||

| 1/2 | 11.9250 | |||

| Cameraman | 512 × 512 | 1/8 | 17.3866 | |

| 1/4 | 14.4083 | |||

| 1/2 | 11.4200 | |||

| Peppers | 512 × 512 | 1/8 | 17.9319 | |

| 1/4 | 14.9453 | |||

| 1/2 | 11.9323 | |||

| Boat | 512 × 512 | 1/8 | 18.3399 | |

| 1/4 | 15.3719 | |||

| 1/2 | 12.3661 | |||

| [38] | Cameraman | 256 × 256 | 1/2 | 11.41 |

| Peppers | 256 × 256 | 1/2 | 11.89 | |

| Boat | 512 × 512 | 1/2 | 12.31 | |

| [37] | Cameraman | 512 × 512 | 1/4 | 14.6359 |

| 1/2 | 11.5825 | |||

| Peppers | 512 × 512 | 1/4 | 14.1524 | |

| 1/2 | 11.2952 | |||

| [32] | Goldhill | 512 × 512 | 1/4 | 14.6848 |

| 1/2 | 11.7152 |

| Images | Algorithm | Encrypted Time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| Cameraman | Ours (256 × 256) | 0.342 |

| Peppers | 0.353 | |

| Baboon | 0.341 | |

| Boat | 0.336 | |

| Cameraman | Ours (512 × 512) | 1.393 |

| Peppers | 1.413 | |

| Baboon | 1.522 | |

| Boat | 1.418 | |

| Cameraman | [41] (256 × 256) | 0.41 |

| [35] (256 × 256) | 0.421 | |

| [40] (256 × 256) | 0.3651 | |

| Baboon | [41] (256 × 256) | 0.38 |

| Test Images | Information Entropy | Correlation Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal | Vertical | Diagonal | |||

| Baboon Peppers | 7.9975 | 227.56 | 0.0035 | −0.0050 | −0.0056 |

| Baboon Boat | 7.9972 | 255.87 | 0.0045 | −0.0046 | 0.0028 |

| Peppers Boat | 7.9973 | 248.27 | 0.0026 | 0.0121 | 0.0043 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, X.; Chai, Y.; Xiang, S.; Li, S. Research on Image Encryption with Multi-Level Keys Based on a Six-Dimensional Memristive Chaotic System. Entropy 2025, 27, 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111152

Zhang X, Chai Y, Xiang S, Li S. Research on Image Encryption with Multi-Level Keys Based on a Six-Dimensional Memristive Chaotic System. Entropy. 2025; 27(11):1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111152

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Xiaobin, Yaxuan Chai, Shitao Xiang, and Shaozhen Li. 2025. "Research on Image Encryption with Multi-Level Keys Based on a Six-Dimensional Memristive Chaotic System" Entropy 27, no. 11: 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111152

APA StyleZhang, X., Chai, Y., Xiang, S., & Li, S. (2025). Research on Image Encryption with Multi-Level Keys Based on a Six-Dimensional Memristive Chaotic System. Entropy, 27(11), 1152. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111152