Interactions Among Morphology, Word Order, and Syntactic Directionality: Evidence from 55 Languages

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Data

2.2. Metrics

2.2.1. Metric for Morphological Richness

- (1)

- MAMSPwhere N refers to the number of text tokens in the data. W represents the window size, where W < N. Fi denotes the number of distinct inflected word forms in each window. Li represents the number of distinct word lemmas in each window. To illustrate, consider the following Japanese sentence:

- (2)

- 朝早く駅に着いて彼女[が omitted]来るのをMorning early ADV station-DAT arrive-GER she-NOM [omitted] come-NMLZ-ACC待ったけど、電車[が omitted]遅れて会えなかった.wait-PST CONJ train-NOM [omitted] late-GER meet-POT-NEG-PST“I arrived early at the station and waited for her to come, but the train was late, so I could not meet her.”

- (3)

- MAMSP = = ≈ 0.548

2.2.2. Metric for Word Order Flexibility

- (4)

- ENTR =

2.2.3. Metric for Syntactic Directionality

- (5)

2.3. Units of Analysis

3. Results

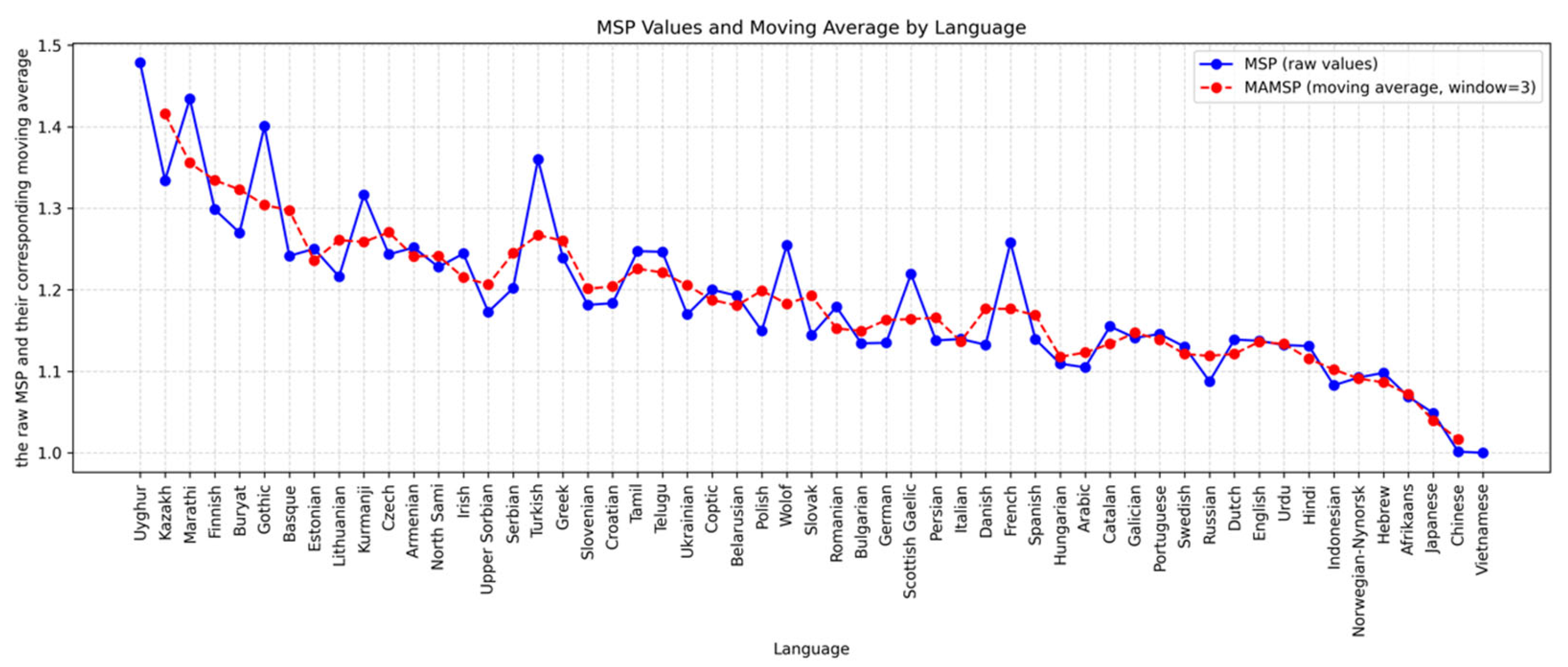

3.1. Morphological Richness

3.2. Syntactic Directionality

3.3. Word Order Flexibility

3.4. Cross-Linguistic Correlations

4. Discussion: Interactions Among Morphology and Syntactic Directionality

5. Summary and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Language Information

| Language Family | Branch | Languages | Morphology | Language Family | Branch | Languages | Morphology |

| Indo-European | Germanic | Afrikaans | Fusional | Indo-European | Slavic | Croatian | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Germanic | Dutch | Fusional | Indo-European | Slavic | Slovenian | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Germanic | Norwegian-Nynorsk | Fusional | Indo-European | Slavic | Serbian | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Germanic | English | Fusional | Indo-European | Slavic | Upper Sorbian | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Germanic | Danish | Fusional | Indo-European | Slavic | Czech | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Germanic | German | Fusional | Indo-European | Greek | Greek | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Germanic | Swedish | Fusional | Indo-European | Baltic | Lithuanian | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Germanic | Gothic | Fusional | Dravidian | Dravidian | Telugu | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Indo-Aryan | Hindi | Fusional | Dravidian | Dravidian | Tamil | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Indo-Aryan | Urdu | Fusional | Uralic | Finno-Ugric | Hungarian | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Indo-Aryan | Marathi | Agglutinative | Uralic | Finno-Ugric | North Sami | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Romance | Portuguese | Fusional | Uralic | Finnic | Estonian | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Romance | Galician | Fusional | Uralic | Finnic | Finnish | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Romance | Catalan | Fusional | Altaic | Mongolic | Buryat | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Romance | Spanish | Fusional | Altaic | Turkic | Kazakh | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Romance | French | Fusional | Altaic | Turkic | Uyghur | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Romance | Romanian | Fusional | Altaic | Turkic | Turkish | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Romance | Italian | Fusional | Afroasiatic | Semitic | Hebrew | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Iranian | Kurmanji | Agglutinative | Afroasiatic | Semitic | Arabic | Fusional |

| Indo-European | Iranian | Persian | Fusional | Afroasiatic | Egyptian | Coptic | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Celtic | Scottish Gaelic | Fusional | Sino-Tibetan | Sinitic | Chinese | Isolating |

| Indo-European | Celtic | Irish | Fusional | Japanese | Japanese | Japanese | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Slavic | Bulgarian | Fusional | Austronesian | Malayo-Polynesian | Indonesian | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Slavic | Russian | Fusional | Armenian | Armenian | Armenian | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Slavic | Slovak | Fusional | Basque | Basque | Basque | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Slavic | Polish | Fusional | Niger-Congo | Atlantic | Wolof | Agglutinative |

| Indo-European | Slavic | Belarusian | Fusional | Austroasiatic | Vietic | Vietnamese | Isolating |

| Indo-European | Slavic | Ukrainian | Fusional |

Appendix B. Treebank Information

| Language Branch | Treebanks | Text Types | Words | Sentences |

| Armenian | Armenian-ArmTDP | Blog, fiction, grammar-examples, nonfiction, news, legal | 52,585 | 2500 |

| Armenian | Armenian-BSUT | Blog, fiction, government, web, wiki, nonfiction, news, legal | 41,805 | 2300 |

| Basque | Basque-BDT | News | 121,443 | 8993 |

| Germanic | Afrikaans-AfriBooms | Legal nonfiction | 49,260 | 1934 |

| Germanic | German-HDT | News, nonfiction, web | 3,455,580 | 189,928 |

| Germanic | German-GSD | Review, wiki, news | 292,769 | 15,590 |

| Germanic | Danish-DDT | Fiction, nonfiction, news, spoken | 100,733 | 5512 |

| Germanic | Dutch-Alpino | News | 208,748 | 13,603 |

| Germanic | Dutch-LassySmall | Wiki | 98,241 | 7341 |

| Germanic | English-GUM | Academic, blog, email, fiction, government, grammar-examples, legal, medical, news, nonfiction, poetry, reviews, social, spoken, web, wiki | 187,515 | 10,761 |

| Germanic | Swedish-Talbanken | News, nonfiction | 96,859 | 6026 |

| Germanic | Swedish_LinES | Spoken, fiction, nonfiction | 90,960 | 5243 |

| Germanic | Swedish-PUD | News, wiki | 19,085 | 1000 |

| Germanic | Gothic | Bible | 55,336 | 5401 |

| Germanic | Norwegian-Nynorsk | Blog, news, nonfiction | 301,353 | 17,575 |

| Slavic | Slovenian-SSJ | Fiction, news, nonfiction | 267,097 | 16,623 |

| Slavic | Spoken Slovenian | Spoken | 29,488 | 3188 |

| Slavic | Ukrainian-IU | Blog, email, fiction, grammar-examples, legal, news, reviews, social, web, wiki | 122,983 | 7092 |

| Slavic | Serbian-SET | News | 97,673 | 4384 |

| Slavic | Belarusian-HSE | Fiction, legal, news, notification, web, social, wiki | 305,417 | 25,231 |

| Slavic | Bulgarian-BTB | Fiction, legal, news | 156,149 | 11,138 |

| Slavic | Croatian-SET | News, web, wiki | 199,409 | 9010 |

| Slavic | Czech-CAC | Fiction, legal, medical, news, nonfiction, wiki, reviews | 495,497 | 24,709 |

| Slavic | Czech-PDT | News, nonfiction, reviews | 1,530,008 | 87,907 |

| Slavic | Polish-LFG | Fiction, news, social, spoken, nonfiction | 130,967 | 17,246 |

| Slavic | Russian-Taiga | Fiction, news, wiki, blog, email, nonfiction, poetry, social | 197,001 | 17,872 |

| Slavic | Slovak-SNK | Fiction, news, nonfiction | 106,184 | 10,604 |

| Slavic | Upper Sorbian-UFAL | Wiki, nonfiction | 11,196 | 646 |

| Japanese | Japanese-BCCWJ | Fiction, news, blog, conference, nonfiction | 1,253,903 | 57,109 |

| Dravidian | Tamil-TTB | News | 9581 | 600 |

| Dravidian | Tamil-MWTT | News | 2584 | 534 |

| Dravidian | Telugu_MTG | Grammar-examples | 6465 | 1328 |

| Altaic | Buryat-BDT | Grammar examples, news, fiction | 10,185 | 927 |

| Altaic | Kazakh-KTB | News, fiction, wiki | 10,536 | 1078 |

| Altaic | Turkish-Kenet | News, nonfiction | 183,555 | 16,396 |

| Altaic | Turkish-Boun | News, nonfiction | 125,212 | 9761 |

| Altaic | Uyghur_UDT | Fiction | 40,236 | 3456 |

| Romance | Catalan-AnCora | News | 553,042 | 16,678 |

| Greek | Greek-GUD | Grammar examples | 25,493 | 1807 |

| Greek | Greek-GDT | Wiki, news, spoken | 63,441 | 2521 |

| Romance | French-Rhapsodie | Spoken | 44,242 | 3209 |

| Romance | French-Paris Stories | Spoken | 42,795 | 2776 |

| Romance | French-GSD | Blog, news, review, wiki | 400,489 | 16,342 |

| Romance | Spanish-PUD | News, wiki | 23,287 | 1000 |

| Romance | Spanish-AnCora | News | 567,894 | 17,662 |

| Romance | Spanish-GSD | Blog, news, review, wiki | 431,584 | 16,013 |

| Romance | Galician-TreeGal | News | 25,548 | 1000 |

| Romance | Italian-VIT | News, nonfiction | 280,154 | 10,087 |

| Romance | Portuguese-Bosque | News | 227,827 | 9357 |

| Romance | Portuguese-PUD | News, wiki | 23,407 | 1000 |

| Romance | Romanian-RRT | Academic, legal, fiction, medical, nonfiction, news, wiki, | 218,522 | 9524 |

| Indo-Aryan | Hindi-HDTB | News | 351,704 | 16,649 |

| Indo-Aryan | Hindi-PUD | News, wiki | 23,829 | 1000 |

| Indo-Aryan | Marathi-UFAL | Wiki, fiction | 3847 | 466 |

| Indo-Aryan | Urdu-UDTB | News | 138,077 | 5130 |

| Baltic | Lithuanian-ALKSNIS | News, fiction, nonfiction, legal | 70,051 | 3642 |

| Baltic | Lithuanian-HSE | News, nonfiction | 5356 | 263 |

| Celtic | Irish-IDT | News, web, fiction, government, legal | 115,990 | 4910 |

| Celtic | Irish-twitter | Social | 47,790 | 2596 |

| Celtic | Scottish Gaelic | Fiction, news, nonfiction, spoken | 89,958 | 4741 |

| Austronesian | Indonesian-PUD | News, wiki | 19,446 | 1000 |

| Austronesian | Indonesian-GSD | Blog, news | 122,019 | 5598 |

| Austronesian | Indonesian-CSUI | News, nonfiction | 28,263 | 1030 |

| Austroasiatic | Vietnamese-VTB | News | 58,069 | 3323 |

| Niger-Congo Atlantic | Wolof-WTB | Bible, wiki | 44,258 | 2107 |

| Afroasiatic | Arabic-PUD | News, wiki | 20,747 | 1000 |

| Afroasiatic | Arabic-NYUAD | News | 738,889 | 19,738 |

| Afroasiatic | Hebrew-IAHLT Twiki | Wiki | 140,950 | 5039 |

| Afroasiatic | Hebrew-HTB | News | 160,195 | 6143 |

| Afroasiatic | Coptic-Scriptorium | Bible, fiction, nonfiction | 55,858 | 2163 |

| Afroasiatic | Maltese_MUDT | News, nonfiction, legal, fiction, wiki | 44,162 | 2074 |

| Uralic | Estonian-EDT | Fiction, academic, news, nonfiction | 438,245 | 30,968 |

| Uralic | Finnish-TDT | Fiction, legal, news, blog, grammar-examples, | 202,453 | 15,136 |

| Uralic | Finnish-TDT | Poetry, medical, social, web | 19,382 | 2122 |

| Uralic | North Sami-Giella | News, nonfiction | 26,845 | 3122 |

| Uralic | Hungarian-Szeged | News | 42,032 | 1800 |

| Sino-Tibetan Sinitic | Chinese-GSDSimp | Wiki | 123,291 | 4997 |

| Iranian | Kurmanji_MG | Fiction, wiki | 10,260 | 754 |

| Iranian | Persian-PerDT | academic, blog, fiction, news, nonfiction, web | 501,776 | 29.107 |

| Iranian | Persian-Seraji | fiction, legal, medical, news, nonfiction, social, spoken | 152,920 | 5997 |

Appendix C. Morphological Richness (MAMSP) Values in Ascending Order

| Branch | Language | MAMSP | Branch | Language | MAMSP |

| Vietic | Vietnamese | 1 | Romance | Romanian | 1.1791 |

| Sinitic | Chinese | 1.0015 | Slavic | Slovenian | 1.1815 |

| Japanese | Japanese | 1.0488 | Slavic | Croatian | 1.1836 |

| Germanic | Afrikaans | 1.0687 | Slavic | Belarusian | 1.1928 |

| Malayo-Polynesian | Indonesian | 1.0829 | Egyptian | Coptic | 1.2001 |

| Slavic | Russian | 1.0877 | Slavic | Serbian | 1.202 |

| Germanic | Norwegian-Nynorsk | 1.0924 | Baltic | Lithuanian | 1.2162 |

| Semitic | Hebrew | 1.0982 | Celtic | Scottish Gaelic | 1.2195 |

| Semitic | Arabic | 1.1049 | Finno-Ugric | North Sami | 1.228 |

| Finno-Ugric | Hungarian | 1.1094 | Greek | Greek | 1.2391 |

| Germanic | Swedish | 1.1302 | Basque | Basque | 1.2416 |

| Indo-Aryan | Hindi | 1.131 | Slavic | Czech | 1.2435 |

| Indo-Aryan | Urdu | 1.1323 | Celtic | Irish | 1.2444 |

| Germanic | Danish | 1.1326 | Dravidian | Telugu | 1.2466 |

| Slavic | Bulgarian | 1.1344 | Dravidian | Tamil | 1.2474 |

| Germanic | German | 1.135 | Finnic | Estonian | 1.2503 |

| Germanic | English | 1.1375 | Armenian | Armenian | 1.2518 |

| Iranian | Persian | 1.1379 | Atlantic | Wolof | 1.2545 |

| Germanic | Dutch | 1.139 | Romance | French | 1.258 |

| Romance | Spanish | 1.1393 | Mongolic | Buryat | 1.27 |

| Romance | Italian | 1.1397 | Finnic | Finnish | 1.2985 |

| Romance | Galician | 1.1411 | Iranian | Kurmanji | 1.3164 |

| Slavic | Slovak | 1.1445 | Turkic | Kazakh | 1.3341 |

| Romance | Portuguese | 1.1458 | Turkic | Turkish | 1.36 |

| Slavic | Polish | 1.1496 | Germanic | Gothic | 1.4006 |

| Romance | Catalan | 1.1551 | Indo-Aryan | Marathi | 1.4344 |

| Slavic | Ukrainian | 1.1698 | Turkic | Uyghur | 1.4785 |

| Slavic | Upper Sorbian | 1.1729 |

Appendix D. Head-Final Dependency Counts and Percentages

| rank | deprel | head_final | head_final_pct_within_deprel | total_for_deprel | share_of_corpus_pct |

| 1 | case | 84,589 | 96.26 | 87,876 | 10.26 |

| 2 | amod | 49,069 | 82.06 | 59,797 | 6.98 |

| 3 | punct | 48,296 | 39.06 | 123,651 | 14.44 |

| 4 | nsubj | 45,450 | 78.33 | 58,025 | 6.78 |

| 5 | det | 44,673 | 95.65 | 46,705 | 5.45 |

| 6 | advmod | 31,399 | 75.89 | 41,373 | 4.83 |

| 7 | cc | 28,192 | 92.25 | 30,560 | 3.57 |

| 8 | mark | 20,803 | 97.08 | 21,429 | 2.50 |

| 9 | obl | 20,126 | 39.31 | 51,201 | 5.98 |

| 10 | aux | 14,811 | 75.79 | 19,542 | 2.28 |

| 11 | cop | 12,460 | 77.56 | 16,064 | 1.88 |

| 12 | obj | 11,085 | 29.28 | 37,864 | 4.42 |

| 13 | nmod | 9688 | 13.84 | 69,981 | 8.17 |

| 14 | nummod | 7669 | 72.76 | 10,540 | 1.23 |

| 15 | advmod:emph | 6119 | 83.67 | 7313 | 0.85 |

| 16 | advcl | 4488 | 39.71 | 11,301 | 1.32 |

| 17 | expl:pv | 3895 | 77.33 | 5037 | 0.59 |

| 18 | compound | 2965 | 65.82 | 4505 | 0.53 |

| 19 | nsubj:pass | 2948 | 77.62 | 3798 | 0.44 |

| 20 | nmod:poss | 2758 | 43.04 | 6408 | 0.75 |

| 21 | obl:arg | 2639 | 32.29 | 8174 | 0.95 |

| 22 | aux:pass | 2590 | 90.50 | 2862 | 0.33 |

| 23 | nummod:gov | 2455 | 98.79 | 2485 | 0.29 |

| 24 | expl | 1538 | 78.51 | 1959 | 0.23 |

| 25 | xcomp | 1267 | 12.18 | 10,404 | 1.21 |

| 26 | amod:att | 1205 | 99.18 | 1215 | 0.14 |

| 27 | ccomp | 1178 | 12.25 | 9615 | 1.12 |

| 28 | discourse | 1131 | 65.53 | 1726 | 0.20 |

| 29 | expl:pass | 974 | 81.30 | 1198 | 0.14 |

| 30 | dep | 972 | 24.87 | 3909 | 0.46 |

| 31 | mark:prt | 908 | 99.23 | 915 | 0.11 |

| 32 | acl | 894 | 14.68 | 6091 | 0.71 |

| 33 | parataxis | 815 | 15.36 | 5305 | 0.62 |

| 34 | nsubj:cop | 758 | 76.64 | 989 | 0.12 |

| 35 | compound:lvc | 744 | 98.41 | 756 | 0.09 |

| 36 | iobj | 698 | 34.22 | 2040 | 0.24 |

| 37 | nmod:att | 583 | 98.81 | 590 | 0.07 |

| 38 | dislocated | 448 | 80.43 | 557 | 0.07 |

| 39 | advmod:mode | 366 | 91.50 | 400 | 0.05 |

| 40 | det:poss | 362 | 99.18 | 365 | 0.04 |

| 41 | case:gen | 338 | 100.00 | 338 | 0.04 |

| 42 | det:numgov | 305 | 97.76 | 312 | 0.04 |

| 43 | acl:relcl | 300 | 3.71 | 8097 | 0.95 |

| 44 | csubj | 289 | 15.72 | 1838 | 0.21 |

| 45 | vocative | 239 | 64.25 | 372 | 0.04 |

| 46 | obl:tmod | 233 | 54.57 | 427 | 0.05 |

| 47 | advmod:tlocy | 210 | 92.11 | 228 | 0.03 |

| 48 | clf:det | 201 | 99.01 | 203 | 0.02 |

| 49 | orphan | 192 | 22.59 | 850 | 0.10 |

| 50 | advmod:neg | 180 | 96.26 | 187 | 0.02 |

| 51 | compound:prt | 161 | 20.46 | 787 | 0.09 |

| 52 | nmod:tmod | 152 | 92.12 | 165 | 0.02 |

| 53 | aux:neg | 138 | 92.62 | 149 | 0.02 |

| 54 | aux:tense | 131 | 99.24 | 132 | 0.02 |

| 55 | case:acc | 126 | 100.00 | 126 | 0.01 |

| 56 | compound:nn | 123 | 100.00 | 123 | 0.01 |

| 57 | det:nummod | 110 | 97.35 | 113 | 0.01 |

| 58 | obl:mod | 86 | 24.71 | 348 | 0.04 |

| 59 | nmod:gobj | 73 | 98.65 | 74 | 0.01 |

| 60 | advmod:adj | 65 | 42.48 | 153 | 0.02 |

| 61 | nmod:unmarked | 62 | 24.90 | 249 | 0.03 |

| 62 | cc:preconj | 58 | 98.31 | 59 | 0.01 |

| 63 | obl:unmarked | 57 | 33.33 | 171 | 0.02 |

| 64 | nsubj:outer | 52 | 96.30 | 54 | 0.01 |

| 65 | det:predet | 51 | 100.00 | 51 | 0.01 |

| 66 | clf | 43 | 15.25 | 282 | 0.03 |

| 67 | obl:agent | 41 | 8.47 | 484 | 0.06 |

| 68 | expl:subj | 40 | 86.96 | 46 | 0.01 |

| 69 | mark:pcomp | 39 | 100.00 | 39 | 0.00 |

| 70 | expl:poss | 34 | 89.47 | 38 | 0.00 |

| 71 | nmod:desc | 33 | 100.00 | 33 | 0.00 |

| 72 | nmod:npmod | 28 | 73.68 | 38 | 0.00 |

| 73 | advmod:locy | 28 | 90.32 | 31 | 0.00 |

| 74 | nmod:obl | 28 | 70.00 | 40 | 0.00 |

| 75 | expl:impers | 27 | 100.00 | 27 | 0.00 |

| 76 | nmod:gsubj | 26 | 100.00 | 26 | 0.00 |

| 77 | reparandum | 25 | 92.59 | 27 | 0.00 |

| 78 | case:voc | 24 | 100.00 | 24 | 0.00 |

| 79 | obl:patient | 22 | 100.00 | 22 | 0.00 |

| 80 | list | 20 | 4.44 | 450 | 0.05 |

| 81 | obl:comp | 18 | 11.04 | 163 | 0.02 |

| 82 | xcomp:pred | 15 | 1.78 | 842 | 0.10 |

| 83 | compound:preverb | 14 | 12.84 | 109 | 0.01 |

| 84 | nsubj:nn | 14 | 100.00 | 14 | 0.00 |

| 85 | ccomp:obj | 13 | 39.39 | 33 | 0.00 |

| 86 | csubj:vsubj | 13 | 100.00 | 13 | 0.00 |

| 87 | case:adv | 13 | 76.47 | 17 | 0.00 |

| 88 | expl:comp | 13 | 100.00 | 13 | 0.00 |

| 89 | compound:affix | 12 | 92.31 | 13 | 0.00 |

| 90 | aux:caus | 12 | 100.00 | 12 | 0.00 |

| 91 | advmod:tmod | 11 | 91.67 | 12 | 0.00 |

| 92 | advmod:tto | 10 | 100.00 | 10 | 0.00 |

| 93 | csubj:pass | 10 | 6.94 | 144 | 0.02 |

| 94 | obl:appl | 10 | 40.00 | 25 | 0.00 |

| 95 | obj:lvc | 9 | 31.03 | 29 | 0.00 |

| 96 | obl:pmod | 7 | 6.19 | 113 | 0.01 |

| 97 | nmod:lmod | 7 | 100.00 | 7 | 0.00 |

| 98 | csubj:asubj | 6 | 100.00 | 6 | 0.00 |

| 99 | det:pmod | 6 | 3.17 | 189 | 0.02 |

| 100 | nsubj:caus | 5 | 100.00 | 5 | 0.00 |

| 101 | advmod:tfrom | 5 | 83.33 | 6 | 0.00 |

| 102 | obl:adj | 5 | 29.41 | 17 | 0.00 |

| 103 | nsubj:nc | 5 | 100.00 | 5 | 0.00 |

| 104 | csubj:cop | 5 | 3.70 | 135 | 0.02 |

| 105 | xcomp:ds | 5 | 8.47 | 59 | 0.01 |

| 106 | advmod:to | 4 | 66.67 | 6 | 0.00 |

| 107 | obj:appl | 4 | 36.36 | 11 | 0.00 |

| 108 | compound:svc | 4 | 3.45 | 116 | 0.01 |

| 109 | advcl:cond | 4 | 100.00 | 4 | 0.00 |

| 110 | cop:own | 4 | 11.76 | 34 | 0.00 |

| 111 | advcl:cmp | 4 | 28.57 | 14 | 0.00 |

| 112 | ccomp:obl | 3 | 9.38 | 32 | 0.00 |

| 113 | obl:lvc | 3 | 50.00 | 6 | 0.00 |

| 114 | parataxis:discourse | 3 | 100.00 | 3 | 0.00 |

| 115 | obj:caus | 3 | 15.79 | 19 | 0.00 |

| 116 | nsubj:xsubj | 3 | 60.00 | 5 | 0.00 |

| 117 | advcl:objective | 3 | 4.69 | 64 | 0.01 |

| 118 | csubj:outer | 3 | 42.86 | 7 | 0.00 |

| 119 | parataxis:insert | 3 | 23.08 | 13 | 0.00 |

| 120 | iobj:appl | 2 | 66.67 | 3 | 0.00 |

| 121 | obl:prep | 2 | 0.93 | 215 | 0.03 |

| 122 | acl:subj | 2 | 1.41 | 142 | 0.02 |

| 123 | obl:cmp | 2 | 100.00 | 2 | 0.00 |

| 124 | compound:redup | 2 | 22.22 | 9 | 0.00 |

| 125 | advcl:tcl | 2 | 40.00 | 5 | 0.00 |

| 126 | iobj:agent | 2 | 66.67 | 3 | 0.00 |

| 127 | obl:dat | 1 | 0.88 | 114 | 0.01 |

| 128 | advmod:que | 1 | 25.00 | 4 | 0.00 |

| 129 | advcl:pred | 1 | 100.00 | 1 | 0.00 |

| 130 | obl:with | 1 | 2.04 | 49 | 0.01 |

| 131 | obl:adv | 1 | 100.00 | 1 | 0.00 |

| 132 | compound:z | 1 | 100.00 | 1 | 0.00 |

| 133 | advmod:lmod | 1 | 2.08 | 48 | 0.01 |

| 134 | obj:agent | 1 | 14.29 | 7 | 0.00 |

Appendix E. Values of Word Order Flexibility (ENTR) in Ascending Order

| Branch | Languages | ENTR | Branch | Languages | ENTR |

| Vietic | Vietnamese | 0.247 | Slavic | Polish | 0.9109 |

| Sinitic | Chinese | 0.2985 | Slavic | Ukrainian | 0.9251 |

| Indo-Aryan | Hindi | 0.3311 | Slavic | Upper Sorbian | 0.9501 |

| Japanese | Japanese | 0.54 | Egyptian | Coptic | 0.9546 |

| Iranian | Persian | 0.5547 | Mongolic | Buryat | 0.9685 |

| Finnic | Estonian | 0.5821 | Romance | Romanian | 0.9823 |

| Germanic | Norwegian-Nynorsk | 0.6191 | Slavic | Croatian | 0.985 |

| Celtic | Scottish Gaelic | 0.6439 | Romance | Catalan | 0.9851 |

| Indo-Aryan | Urdu | 0.6515 | Germanic | Gothic | 0.9871 |

| Germanic | English | 0.6579 | Finno-Ugric | Hungarian | 1.0001 |

| Turkic | Turkish | 0.6888 | Finno-Ugric | North Sami | 1.0021 |

| Germanic | Swedish | 0.6923 | Armenian | Armenian | 1.0033 |

| Semitic | Arabic | 0.7068 | Greek | Greek | 1.0126 |

| Romance | French | 0.7073 | Romance | Spanish | 1.0194 |

| Romance | Portuguese | 0.7133 | Romance | Italian | 1.0198 |

| Semitic | Hebrew | 0.7134 | Basque | Basque | 1.0293 |

| Romance | Galician | 0.7136 | Slavic | Bulgarian | 1.1011 |

| Turkic | Uyghur | 0.7179 | Germanic | German | 1.144 |

| Germanic | Danish | 0.7565 | Malayo-Polynesian | Indonesian | 1.1602 |

| Indo-Aryan | Marathi | 0.7813 | Germanic | Dutch | 1.2634 |

| Turkic | Kazakh | 0.7869 | Finnic | Finnish | 1.3202 |

| Dravidian | Telugu | 0.7992 | Slavic | Slovenian | 1.3627 |

| Dravidian | Tamil | 0.8732 | Slavic | Czech | 1.3761 |

| Germanic | Afrikaans | 0.8782 | Iranian | Kurmanji | 1.3791 |

| Slavic | Russian | 0.8962 | Baltic | Lithuanian | 1.3881 |

| Celtic | Irish | 0.9009 | Slavic | Slovak | 1.4232 |

| Slavic | Belarusian | 0.9019 | Atlantic | Wolof | 1.4246 |

| Slavic | Serbian | 0.9059 |

Appendix F. Word Order Distribution of the 55 Languages

| Language | SVO % | SOV % | VSO % | VOS % | OVS % | OSV % | Language | SVO % | SOV % | VSO % | VOS % | OVS % | OSV % |

| Armenian | 0.6895 | 0.2120 | 0.0044 | 0.0049 | 0.0770 | 0.0122 | Portuguese | 0.8109 | 0.0298 | 0.0167 | 0.0401 | 0.1010 | 0.0015 |

| Basque | 0.5884 | 0.3039 | 0.0034 | 0.0170 | 0.0397 | 0.0476 | Romanian | 0.6111 | 0.2450 | 0.0033 | 0.0075 | 0.1305 | 0.0026 |

| Bulgarian | 0.8201 | 0.0544 | 0.0011 | 0.0200 | 0.0994 | 0.0050 | Spanish | 0.6210 | 0.1600 | 0.0110 | 0.0055 | 0.1960 | 0.0065 |

| Belarusian | 0.8544 | 0.0391 | 0.0000 | 0.0177 | 0.0621 | 0.0267 | Catalan | 0.6480 | 0.1548 | 0.0122 | 0.0049 | 0.1740 | 0.0061 |

| Croatian | 0.7344 | 0.0566 | 0.0326 | 0.0567 | 0.0898 | 0.0299 | Greek | 0.5846 | 0.0111 | 0.3011 | 0.0876 | 0.0113 | 0.0043 |

| Czech | 0.5080 | 0.0700 | 0.1010 | 0.1100 | 0.2000 | 0.0110 | Maltese | 0.2411 | 0.0000 | 0.6989 | 0.0411 | 0.0189 | 0.0000 |

| Polish | 0.7398 | 0.0440 | 0.0420 | 0.0520 | 0.1210 | 0.0012 | Arabic | 0.2310 | 0.0000 | 0.7284 | 0.0388 | 0.0018 | 0.0000 |

| Russian | 0.7446 | 0.0389 | 0.0110 | 0.0370 | 0.1387 | 0.0298 | Hebrew | 0.1810 | 0.0000 | 0.0650 | 0.0055 | 0.0110 | 0.0000 |

| Slovak | 0.4720 | 0.1260 | 0.0510 | 0.0780 | 0.2390 | 0.0340 | Coptic | 0.7258 | 0.2460 | 0.0040 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0242 |

| Slovenian | 0.4730 | 0.1680 | 0.0390 | 0.0300 | 0.2490 | 0.0410 | Marathi | 0.1123 | 0.7944 | 0.0156 | 0.0211 | 0.0111 | 0.0455 |

| Serbian | 0.7527 | 0.0540 | 0.0133 | 0.0344 | 0.1122 | 0.0343 | Hindi | 0.0389 | 0.9231 | 0.0000 | 0.0016 | 0.0000 | 0.0364 |

| Ukrainian | 0.7345 | 0.0304 | 0.0156 | 0.0385 | 0.1433 | 0.0377 | Persian | 0.1488 | 0.8233 | 0.0012 | 0.0000 | 0.0017 | 0.0250 |

| Upper Sorbian | 0.7299 | 0.0493 | 0.0187 | 0.0322 | 0.1354 | 0.0345 | Urdu | 0.1520 | 0.7981 | 0.0110 | 0.0000 | 0.0025 | 0.0364 |

| Danish | 0.7968 | 0.0000 | 0.0026 | 0.0000 | 0.0891 | 0.1115 | Indonesian | 0.4818 | 0.0032 | 0.3451 | 0.0343 | 0.1254 | 0.0102 |

| Dutch | 0.5862 | 0.1000 | 0.0030 | 0.1000 | 0.0910 | 0.1198 | Irish | 0.2975 | 0.0007 | 0.6902 | 0.0106 | 0.0000 | 0.0009 |

| English | 0.7965 | 0.0000 | 0.0027 | 0.0000 | 0.0910 | 0.1098 | Scottish Gaelic | 0.2876 | 0.0000 | 0.7044 | 0.0080 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| Afrikaans | 0.6714 | 0.0010 | 0.2007 | 0.0030 | 0.1230 | 0.0009 | Japanese | 0.0000 | 0.8277 | 0.0076 | 0.0060 | 0.0000 | 0.1587 |

| German | 0.4810 | 0.0016 | 0.3480 | 0.0300 | 0.1300 | 0.0094 | Kurmanji | 0.0910 | 0.6391 | 0.0033 | 0.0015 | 0.2630 | 0.0021 |

| Gothic | 0.6729 | 0.2087 | 0.0031 | 0.0374 | 0.0374 | 0.0405 | Lithuanian | 0.5349 | 0.1115 | 0.1925 | 0.1101 | 0.0446 | 0.0064 |

| Norwegian-Nynorsk | 0.6853 | 0.3133 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | Tamil | 0.0000 | 0.6020 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0772 | 0.3208 |

| Swedish | 0.7787 | 0.0000 | 0.0023 | 0.0000 | 0.1002 | 0.1188 | Telugu | 0.0220 | 0.7010 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0360 | 0.2410 |

| Estonian | 0.8497 | 0.0088 | 0.0814 | 0.0091 | 0.0510 | 0.0000 | Turkish | 0.0343 | 0.7798 | 0.0042 | 0.0010 | 0.1510 | 0.0297 |

| Finnish | 0.4147 | 0.0906 | 0.1116 | 0.0000 | 0.1877 | 0.1954 | Kazakh | 0.0301 | 0.7661 | 0.0056 | 0.0020 | 0.1477 | 0.0485 |

| Hungarian | 0.5869 | 0.2243 | 0.0047 | 0.0000 | 0.1280 | 0.0561 | Uyghur | 0.0344 | 0.7886 | 0.0058 | 0.0021 | 0.1412 | 0.0279 |

| North Sami | 0.6075 | 0.2607 | 0.0579 | 0.0020 | 0.0599 | 0.0119 | Buryat | 0.2745 | 0.6009 | 0.0023 | 0.0017 | 0.1001 | 0.0205 |

| French | 0.7887 | 0.0820 | 0.0098 | 0.0000 | 0.1160 | 0.0035 | Vietnamese | 0.9511 | 0.0191 | 0.0000 | 0.0100 | 0.0000 | 0.0198 |

| Galician | 0.7581 | 0.2120 | 0.0075 | 0.0075 | 0.0050 | 0.0100 | Chinese | 0.9311 | 0.0344 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0345 |

| Italian | 0.6117 | 0.1662 | 0.0111 | 0.0059 | 0.2001 | 0.0050 | Wolof | 0.8734 | 0.0240 | 0.0115 | 0.0302 | 0.0255 | 0.0354 |

References

- Fenk-Oczlon, G.; Pilz, J. Linguistic Complexity: Relationships Between Phoneme Inventory Size, Syllable Complexity, Word and Clause Length, and Population Size. Front. Commun. 2021, 6, 626032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnemäki, K. Complexity Trade-Offs: A Case Study. In Measuring Grammatical Complexity; Newmeyer, F., Preston, L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z. On Computational Complexity of Natural Language [Zìrán Yǔyán de Jìsuàn Fùzá Xìng Yánjiū]. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 2015, 659–672. [Google Scholar]

- Levshina, N. Token-Based Typology and Word Order Entropy: A Study Based on Universal Dependencies. Linguist. Typology 2019, 23, 533–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdicevskis, A.; Schmidtke-Bode, K.; Seržant, I. Subjects Tend to Be Coded Only Once: Corpus-Based and Grammar-Based Evidence for an Efficiency-Driven Trade-Off. In Proceedings of the 19th International Workshop on Treebanks and Linguistic Theories; Association for Computational Linguistics: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2020; pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, B.; Yan, J.; Zheng, J. Quantitative Investigation into the Relationship between Word-Class Conversion and the Morphological Typology of Languages. Foreign Lang Teach Res 2023, 55, 497–508. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Qin, H. Multilingual Analysis of Act of Speaking Markers: An Event Encoding Perspective. Foreign Lang. Teach. Res. 2023, 55, 483–496. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J. Morphology and Word Order in Slavic Languages: Insights from Annotated Corpora. Vopr. Jazyk. 2021, 4, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koplenig, A.; Meyer, P.; Wolfer, S.; Müller-Spitzer, C. The Statistical Trade-Off Between Word Order and Word Structure—Large-Scale Evidence for the Principle of Least Effort. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenk-Oczlon, G.; Fenk, A. Measuring Basic Tempo across Languages and Some Implications for Speech Rhythm. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH 2010, 11th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, Makuhari, Chiba, Japan, 26–30 September 2010; ISCA: Singapore; pp. 1537–1540. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnemäki, K. Word Order in Zero-Marking Languages. Stud. Lang. 2010, 34, 869–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Dependency Distance as a Metric of Language Comprehension Difficulty. J. Cogn. Sci. 2008, 9, 159–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, J.A. A Comparative Typology of English and German: Unifying the Contrasts; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, E. Linguistic Complexity: Locality of Syntactic Dependencies. Cognition 1998, 68, 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, J.A. Efficiency and Complexity in Grammars; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-19-925268-8. [Google Scholar]

- Sinnemäki, K.; Haakana, V. Head and Dependent Marking and Dependency Length in Possessive Noun Phrases: A Typological Study of Morphological and Syntactic Complexity. Linguist. Vanguard 2022, 9, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Marneffe, M.-C.; Manning, C.D.; Nivre, J.; Zeman, D. Universal Dependencies. Comput. Linguist. 2021, 47, 255–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çöltekin, Ç.; Rama, T. What Do Complexity Measures Measure? Correlating and Validating Corpus-Based Measures of Morphological Complexity. Linguist. Vanguard 2023, 9, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthos, A.; Gillis, S. Quantifying the Development of Inflectional Diversity. First Lang. 2010, 30, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesnière, L. Éléments de Syntaxe Structurale; Klincksieck: Paris, France, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda, T. Sekai no Gengo to Nihongo [Languages of the World and Japanese]. Kuroshio Publishing: Japan, Tokyo, 2009; Available online: https://www.9640.jp/book_view/?54 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Kubon, V.; Lopatková, M.; Hercig, T. Searching for a Measure of Word Order Freedom. In Proceedings of the 16th ITAT Conference Information Technologies—Applications and Theory; Kubon, V., Lopatková, M., Hercig, T., Brejova, B., Eds.; CEUR: Tatranské Matliare, Slovakia, 2016; Volume 1649. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Liu, H.; Xiong, Z. A Quantitative Analysis of Word Order Freedom and the Abundance of Case Markers in Japanese. Math Linguist 2022, 33, 325–340. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. Dependency Direction as a Means of Word-Order Typology: A Method Based on Dependency Treebanks. Lingua 2010, 120, 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H. The Cross-Linguistic Variations in Dependency Distance Minimization and Its Potential Explanations. In Proceedings of the 37th Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation (PACLIC 2023), Hong Kong, China, 1–3 December 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Hong Kong, China; pp. 559–569. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J.H. A Quantitative Approach to the Morphological Typology of Language. In Method and Perspective in Anthropology; Spencer, R.F., Ed.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1954; pp. 192–220. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, B.; Nichols, J. Inflectional Morphology. In Language Typology and Syntactic Description; Shopen, T., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 169–240. [Google Scholar]

- Dryer, M.S. The Greenbergian Word Order Correlations. Language 1992, 68, 81–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez-Burraco, A.; Chen, S.; Gil, D. The Absence of a Trade-Off Between Morphological and Syntactic Complexity. Front. Lang. Sci. 2024, 3, 1340493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Language/Data Type | SVO (%) | SOV (%) | VSO (%) | VOS (%) | OVS (%) | OSV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic (PUD + NYUAD) | 18.1 | 0.0 | 72.8 | NA | 3.9 | 0.2 |

| Maltese (MUDT) | 24.1 | 0.0 | 69.9 | NA | 4.1 | 1.9 |

| Hebrew-HTB | 16.6 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 1.1 | 0.0 |

| Hebrew-IAHLTwiki | 19.6 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| Language/Data Type | SV (%) | VS (%) | VO (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hebrew-HTB | 44.5 | 25.4 | 8.3 |

| Hebrew-IAHLTwiki | 40.0 | 24.8 | 4.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Liu, H. Interactions Among Morphology, Word Order, and Syntactic Directionality: Evidence from 55 Languages. Entropy 2025, 27, 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111128

Li W, Liu H. Interactions Among Morphology, Word Order, and Syntactic Directionality: Evidence from 55 Languages. Entropy. 2025; 27(11):1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111128

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenchao, and Haitao Liu. 2025. "Interactions Among Morphology, Word Order, and Syntactic Directionality: Evidence from 55 Languages" Entropy 27, no. 11: 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111128

APA StyleLi, W., & Liu, H. (2025). Interactions Among Morphology, Word Order, and Syntactic Directionality: Evidence from 55 Languages. Entropy, 27(11), 1128. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111128