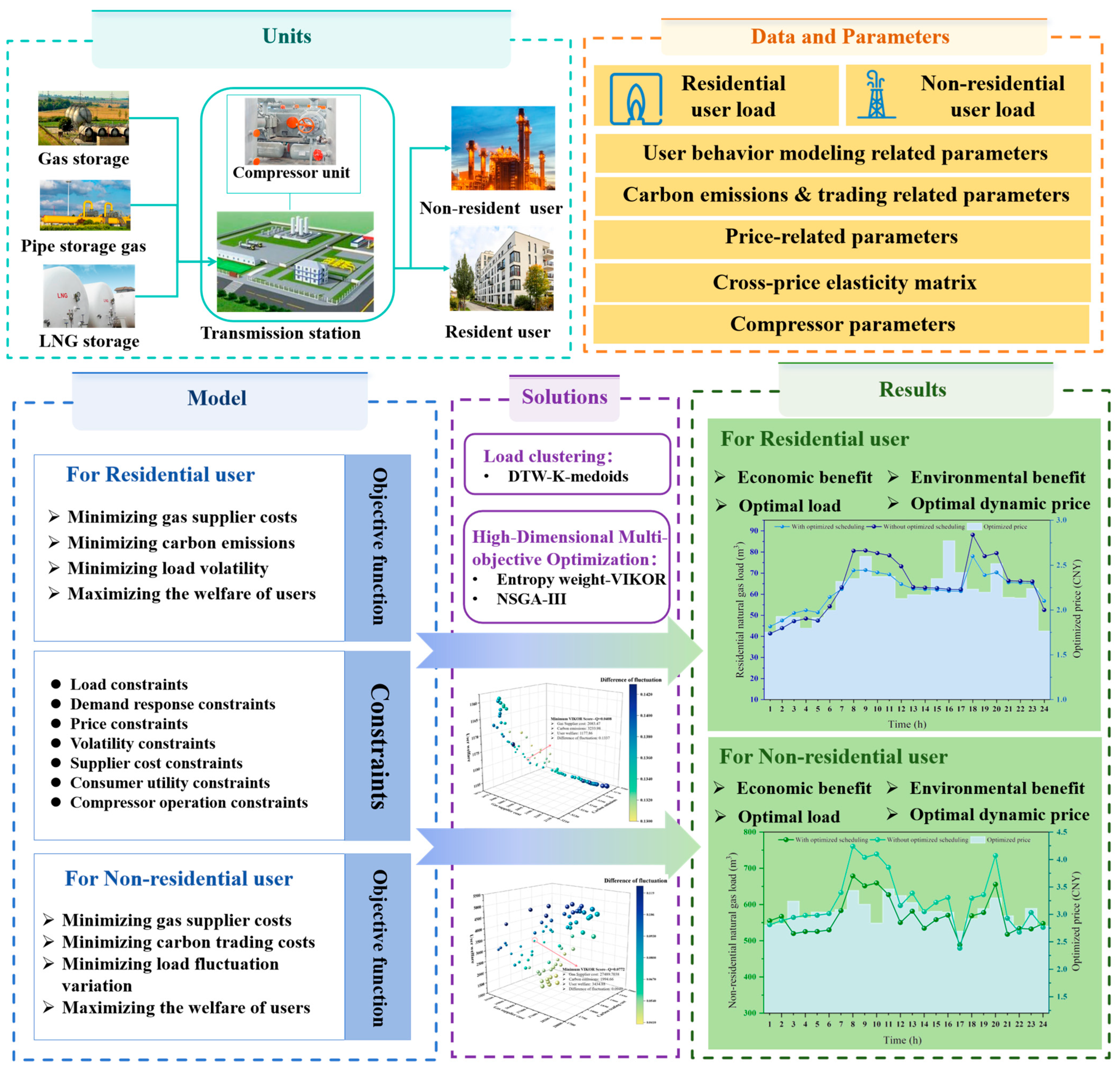

4.1. Data Description and Parameter Description

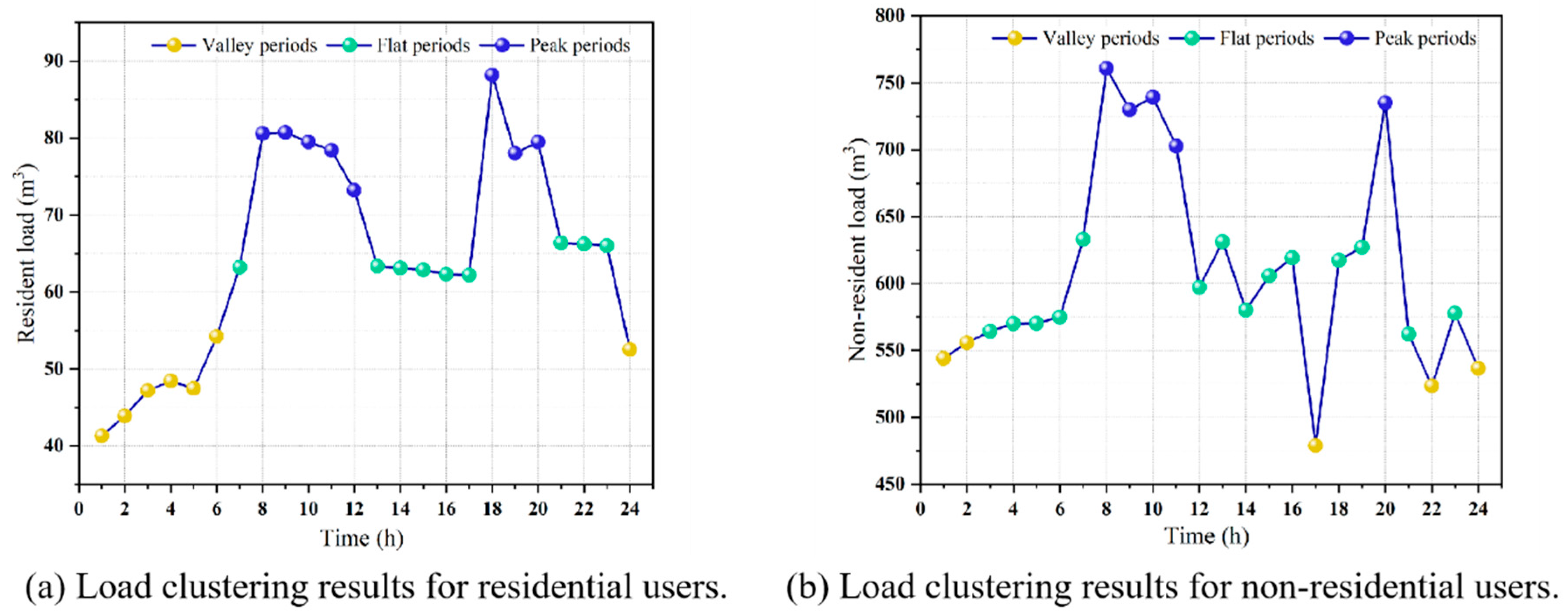

To validate the proposed scheduling model, this study utilizes branch natural gas load data from a gas station in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province in 2020. The dataset captures the load variations in residential and non-residential users over 24 h. To meet data confidentiality requirements, the user data employed consists of field station data that has undergone linear scaling processing. The scaling only adjusts the absolute load range without altering structural features of the time series, such as peak-valley distribution and fluctuation patterns. As the model emphasizes relative load variations and demand response behavior, the use of scaled data does not affect the robustness of the results or the reliability of the conclusions. This study assumes that compressors need to be activated during peak gas demand periods to pressurize the pipeline gas. The detailed compressor model and parameters are provided in

Table S1 of Supplementary Materials. Moreover, natural gas suppliers formulate supply plans at least one scheduling period in advance to satisfy the projected gas demand of regional users. The specific load data used is illustrated in

Figure 4.

Residential load refers to the natural gas consumption required by households within the supply area. Residential demand is usually small in scale and is supplied indirectly through the urban distribution network. Non-residential users typically refer to large natural gas-consuming enterprises that are major emission sources or high-energy-consumption entities. Their natural gas supply needs are usually met through direct supply contracts or medium-to-high-pressure direct supply methods. The scheduling model designed in this study has a time unit of 1 h and a cycle of 24 h. The carbon emission and trading model, as well as the user behavior model parameters for scheduling natural gas load for residential and non-residential users, are provided in

Table 1 [

34,

35,

36,

37]. To enhance the empirical validity of utility function modeling,

and

are determined with reference to relevant literature [

25], and further calibrated based on the observed variations in regional natural gas consumption. It is worth noting that the adjustment of gas consumption behavior by end users exhibits a certain degree of rigidity, as their flexibility is constrained by various factors such as daily routines and industrial processes. Here,

represents the user’s load adjustment acceptance degree, influenced by infrastructure and gas consumption patterns. Based on real-world conditions and user willingness constraints, the upper limit of load variation acceptability is set to no more than 0.1 to reflect the maximum adjustable capacity in actual gas consumption. Meanwhile,

represents the intensity of users’ response to price variations, with its upper limit set at 0.1. Excessively high

causes load inversion, failing to achieve peak shaving and valley filling while inducing user response distortion.

and

serve as relative behavioral modeling parameters designed to reflect the comparative differences between distinct user types, rather than aiming for precise quantitative results. Their ranges may vary across regions or user groups, depending on infrastructure conditions, gas consumption patterns, and users’ willingness to adjust demand. Due to the lack of complete household-level consumption monitoring data and user behavior surveys, this study assumes, based on historical natural gas consumption patterns in Xi’an, that the values of

and

for residential users are 0.05 and 0.02, while for non-residential users they are 0.08 and 0.04. Residential users follow relatively fixed daily routines, and their gas demand is characterized by low substitutability and limited reducibility. As a result, their flexibility in load adjustment remains constrained. In contrast, non-residential users are more sensitive to price changes, primarily due to the higher adaptability of their production schedules. Therefore, the coefficient of price sensitivity and load variation acceptance of residential users is usually lower than that of non-residential users, which also reflects the difference in demand response characteristics of different user categories. Price-related information is presented in

Table 2, with data sourced from the natural gas pricing reform plan released by the Xi’an Development and Reform Commission, as well as the tracking and rating report from Xi’an Infrastructure Investment Group.

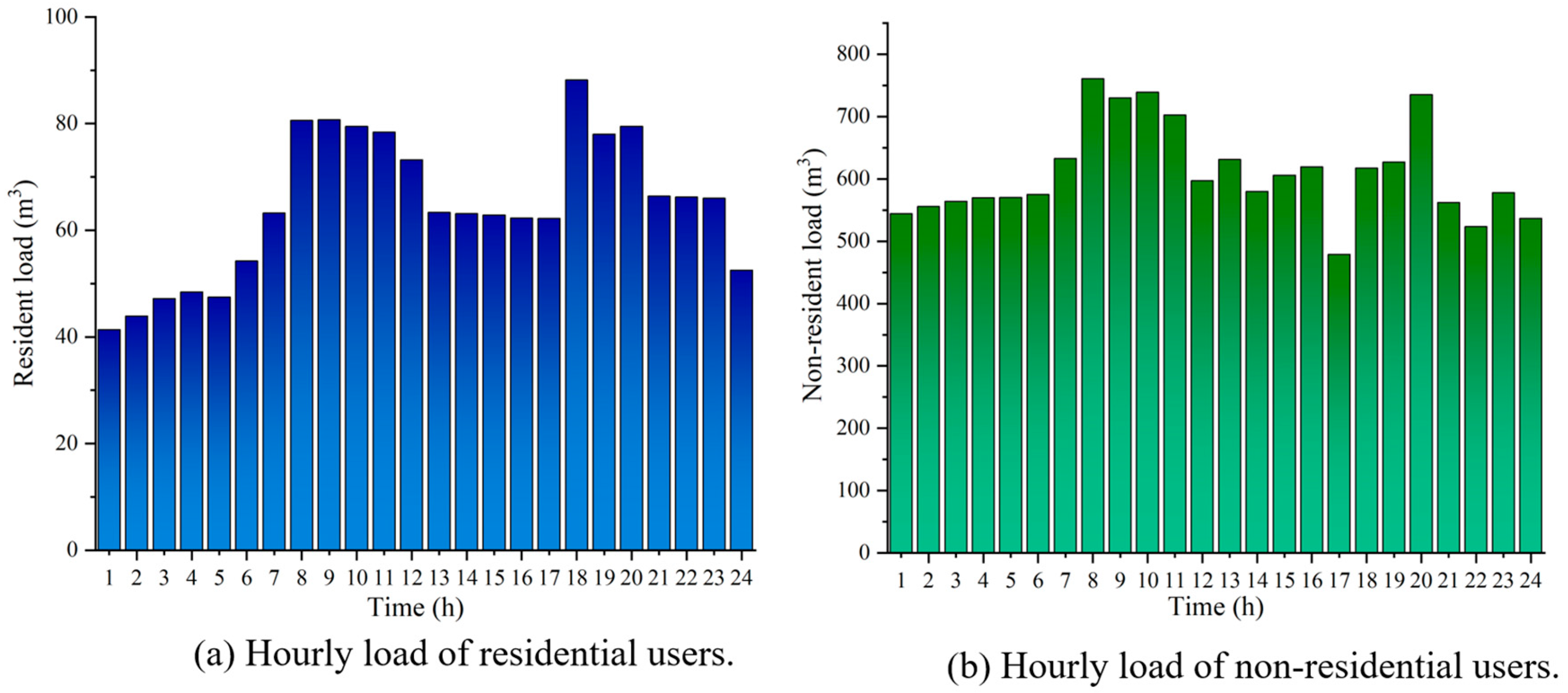

The time-division results of peak, flat, and valley obtained by using DTW-K-medoids in this study are shown in

Figure 5. For residential users, the peak periods are defined as 8:00–12:00 and 18:00–20:00, the flat periods as 7:00, 13:00–17:00, and 21:00–23:00, and the valley periods as 1:00–6:00 and 24:00. For non-residential users, the peak periods are 8:00–11:00 and 20:00, the flat periods are 3:00–7:00, 12:00–16:00, 18:00–19:00, 21:00, and 23:00, while the valley periods are 1:00–2:00, 17:00, 22:00, and 24:00. Through a data-driven approach, it was identified that residential users exhibit a “bimodal” pattern (8:00–12:00, 18:00–20:00), while non-residential users display a “pulsed” peak period (8:00–11:00, 20:00). This segmentation provides a temporal benchmark for the subsequent implementation of differentiated scheduling strategies, enhancing the alignment between dynamic price signals and the actual energy usage patterns of users. Regarding the price elasticity coefficients for different time periods, the literature calculates the own price elasticity coefficient for the residential sector in China to be −0.233 [

38]. The findings align with the consumption characteristics of residential gas users in China. The price elasticity of demand for the non-residential sector in China, as presented in this literature, exhibits behavior contrary to the conventional law of demand due to the limitations imposed by insufficient energy supply. However, the energy resources in Shaanxi Province, selected for this study, are relatively abundant. It is home to one of China’s key natural gas production regions and receives external supplies through the national natural gas backbone network. Consequently, the price elasticity of the non-residential sector aligns with the conventional demand law. Due to the lack of specific statistical data and research on the price elasticity coefficients for non-residential users in Shaanxi Province, this study estimates the required price elasticity coefficients based on the findings from the literature [

39,

40]. The elasticity coefficients for the time-of-use pricing scheme adopted in this study are presented in

Table 3.

4.2. Experimental Results and Strategies

Based on the proposed NGLES model, the dispatch center applies the high-dimensional multi-objective optimization method, as described in

Section 3, to generate a Pareto-optimal solution set. This set represents trade-off solutions under four objectives: cost minimization, carbon emission and trading minimization, user welfare maximization, and load fluctuation minimization, reflecting Pareto efficiency. Subsequently, the dispatch center selects a unique optimal scheduling strategy from the solution set using a MCDM approach. With a decision-making mechanism factor of 0.5, this strategy balances collective utility and individual regret, achieving a synergistic compromise between economic environmental benefits and system stability. The entire process strictly adheres to the principle of uniqueness in single-dispatch strategies, ensuring the global optimality of dispatch instructions and the consistency of execution. For residential users, the scheduling model considers minimizing gas supplier costs, carbon emissions, and load volatility while maximizing residential user welfare. The trade-off solution is indicated by the red markers in

Figure 6a. For non-residential users, the scheduling model seeks to minimize gas supplier costs, ladder-type carbon trading costs, and load volatility, while maximizing user welfare.

Figure 6b highlights the resulting trade-off solution with a red marker.

In order to evaluate the practical scheduling application of the NGLES model for both residential and non-residential users, the NSGA-III-EW-VIKOR is employed as the solution model, with a decision-making mechanism factor of 0.5 used to determine the unique optimal scheduling scheme. Due to the significant differences in gas consumption behavior between residential and non-residential users, the model incorporates differentiated parameter settings for the user utility functions during the user behavior modeling process, aiming to more accurately reflect the decision-making characteristics of different user types. The price sensitivity and load variation acceptance of residential users are set at 0.05 and 0.02, respectively, based on the actual response characteristics of residential users to fluctuations in natural gas prices and load variations. In contrast, non-residential users exhibit a more significant response to price and load changes compared to residential users. Therefore, their price sensitivity and load variation acceptance are set at 0.08 and 0.04, respectively, to better capture their gas consumption elasticity.

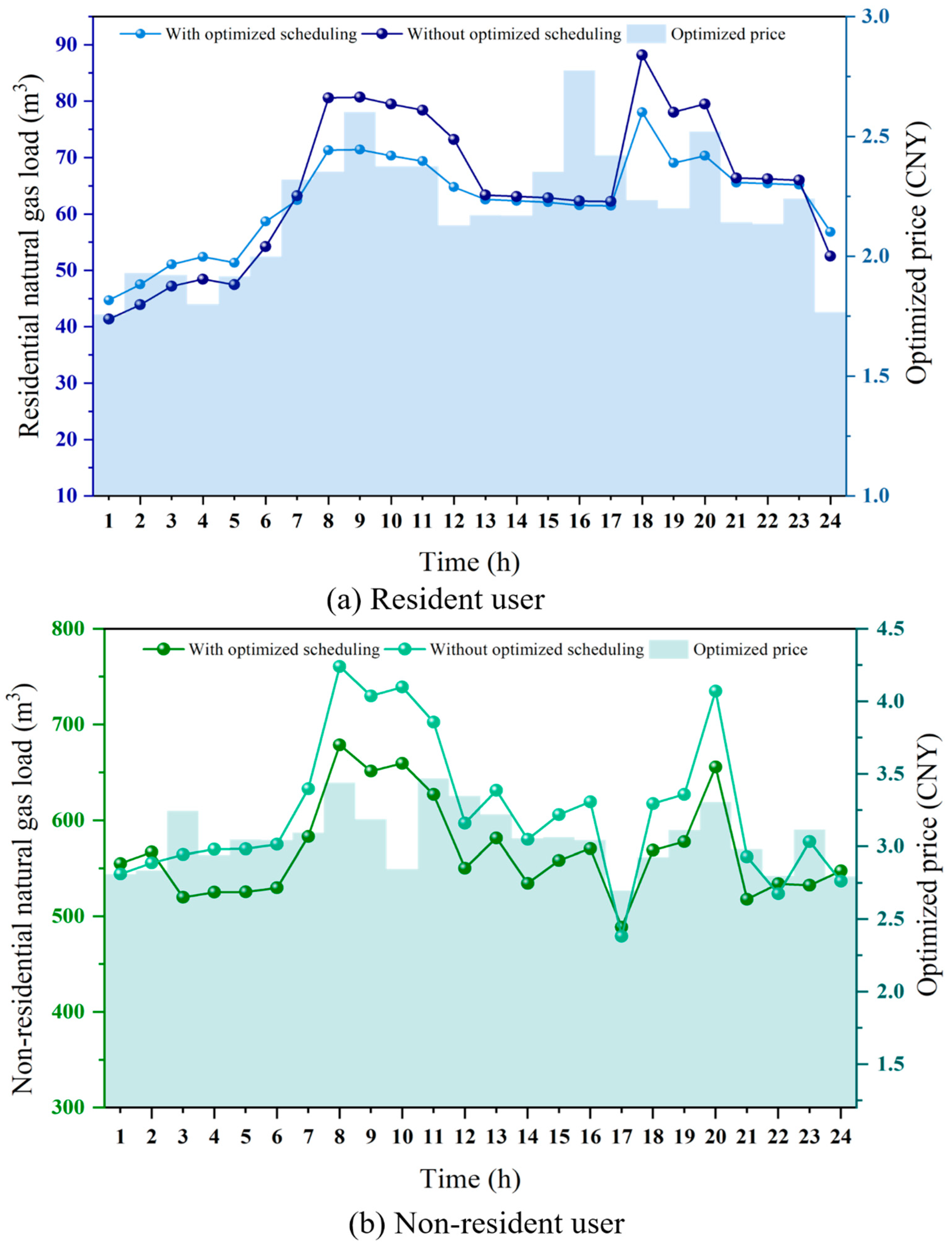

Figure 7a and

Figure 7b illustrate the dynamic natural gas prices and the hourly gas consumption variations for residential and non-residential users under the optimized scheduling scenario, respectively.

Regarding natural gas pricing, before optimization, the terminal price for residential natural gas was 2.18 CNY, while that for non-residential users was 3.04 CNY. After optimization, the real-time gas price exhibited significant temporal differentiation, effectively reflecting the guiding role of price signals in influencing user gas consumption behavior. As shown in

Figure 7a, during the peak gas consumption periods of residential users (08:00–12:00, 18:00–20:00), the dynamic pricing increases from the fixed price of 2.18 CNY to a maximum of 2.78 CNY at 16:00. Considering that dynamic price signals can effectively regulate peak gas consumption among residential users, the total natural gas load is reduced from 1548.96 m

3 to 1495.69 m

3, representing a reduction of 53.27 m

3. This alleviates the pipeline network load pressure and the gas allocation burden during the scheduling process. Meanwhile, the load volatility decreased from 0.2059 to 0.1333, indicating that the proposed NGLCES model significantly enhances the stability of natural gas supply. The peak gas consumption periods for non-residential users occur between 8:00–11:00 and at 20:00. As shown in

Figure 7b, the dynamic pricing mechanism increases the fixed price of 3.04 CNY to a maximum of 3.47 CNY at 11:00. The total natural gas load decreased from 14,638.10 m

3 to 13,640.59 m

3, representing a reduction of 997.51 m

3. Additionally, a portion of the flexible load was shifted from peak periods to valley periods, thereby reducing the peak-to-valley difference. Meanwhile, the natural gas volatility for non-residential users decreased from 0.1221 to 0.0899. This result indicates that appropriate price regulation can effectively mitigate load fluctuations and enhance the operational stability of the system. Non-residential users contribute more to both absolute and relative load reductions and serve as the main source of lowering system peak demand and total consumption. Residential users show smaller reductions in absolute terms, but they play a more significant role in smoothing hourly fluctuations. This supports scheduling stability and reduces short-term balancing costs. The experimental results indicate that the optimized dynamic pricing mechanism achieves dynamic regulation of supply and demand balance between residential and non-residential users, providing a crucial theoretical foundation for the further development of real-time pricing policies in the natural gas sector. The findings validate the effectiveness of dynamic price signals and user behavior modeling in multi-objective optimization scheduling.

In terms of economic benefits, the gas supplier costs and user welfare after scheduling optimization are calculated based on price adjustments and load changes. The gas supplier purchases gas in advance based on the users’ consumption plans.

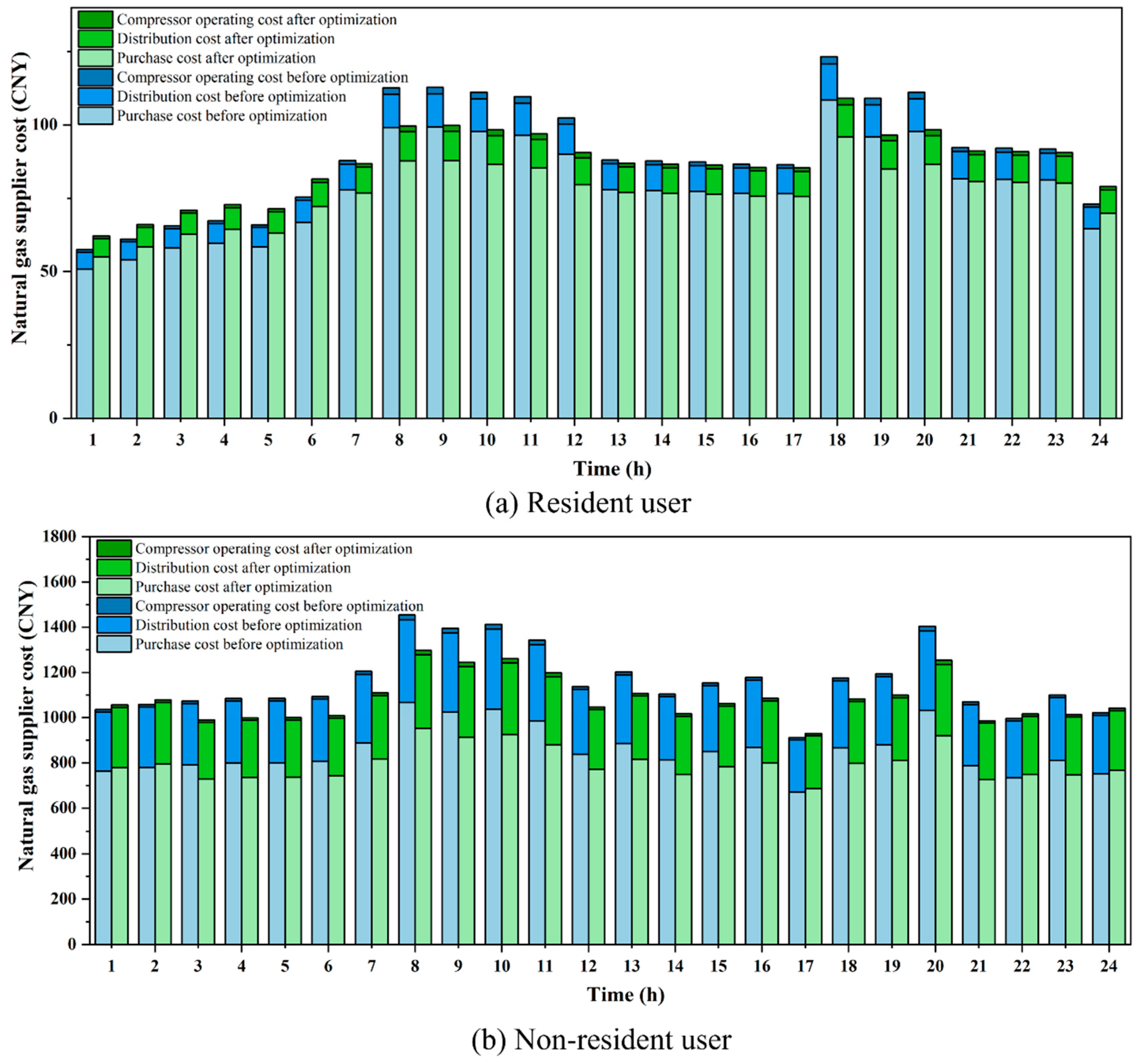

Table 4 presents the gas supply costs, revenues, and profits of the gas supplier required to meet the demand of residential users. The proposed scheduling optimization yields a cost saving of 74.64 CNY for the gas supplier. This reduction includes a decrease of 65.52 CNY in gas procurement costs, 7.45 CNY in distribution costs, and 1.67 CNY in compressor operation costs. The corresponding hourly gas purchase costs, distribution costs, and compressor operation costs before and after scheduling optimization are illustrated in

Figure 8a. Additionally, this study calculates the revenue and profit of the gas supplier, with the optimized results showing an increase of 11.49 CNY in profit compared to the pre-optimization scenario. After optimizing the scheduling strategy, the gas supply cost for suppliers serving residential users increased during valley periods. However, during flat and peak periods, the cost after scheduling optimization significantly decreased, with the most notable reduction observed during the peak periods. This is attributable to the price signals encouraging users to shift part of their gas consumption to the lower-priced off-peak periods, thereby reducing the demand during peak periods. This optimization not only improved gas usage behavior but also effectively alleviated the supply pressure during peak periods, reducing the gas procurement costs and distribution losses during these times.

Table 5 presents detailed information regarding the gas supplier costs, revenue, and profit for non-residential users. After the optimization of the scheduling strategy, the total gas supply cost incurred by the gas supplier for non-residential user gas scheduling was reduced by 1901.39 CNY. Specifically, the costs for gas procurement, transportation and distribution, and compressor operation were reduced by 1399.5 CNY, 478.81 CNY, and 23.08 CNY, respectively. The gas supplier’s revenue decreased by 746.32 CNY compared to the pre-optimization scenario. The corresponding comparison of hourly gas purchase costs, gas distribution costs, and compressor operating costs before and after the scheduling optimization is illustrated in

Figure 8b. For non-residential users, particularly large industrial users, there is a distinct difference in gas demand compared to residential users. These users exhibit a higher sensitivity to price signals and have relatively flexible gas consumption schedules. Therefore, after the optimization of the scheduling, the gas supply costs for the supplier significantly decrease during flat and peak periods, while costs during the valley period experience a slight increase. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the lower natural gas prices during valley periods, which allow large industrial users to flexibly adjust their operating hours or production processes, thereby shifting some of their energy consumption to lower-price periods. This load-shifting strategy not only helps users reduce gas consumption costs but also effectively alleviates the supply pressure during peak periods. It is noteworthy that the gas supplier’s revenue decreased after optimization. This is attributed to non-residential users adjusting their gas consumption schedules to periods with lower gas prices or switching to alternative energy sources, resulting in reduced purchasing revenue for the gas supplier, thereby leading to a decline in the supplier’s profit. In response to this situation, policy incentives are required to compensate gas suppliers in order to offset the economic losses incurred from ensuring the stability of the gas scheduling system and the safety of transportation. In addition, the operating costs of compressors during peak periods are higher compared to off-peak and valley periods. This is primarily due to the significant increase in gas demand during peak periods, which necessitates the use of compressors to maintain the stability of the gas pipeline network, thereby ensuring the normal gas supply during peak times.

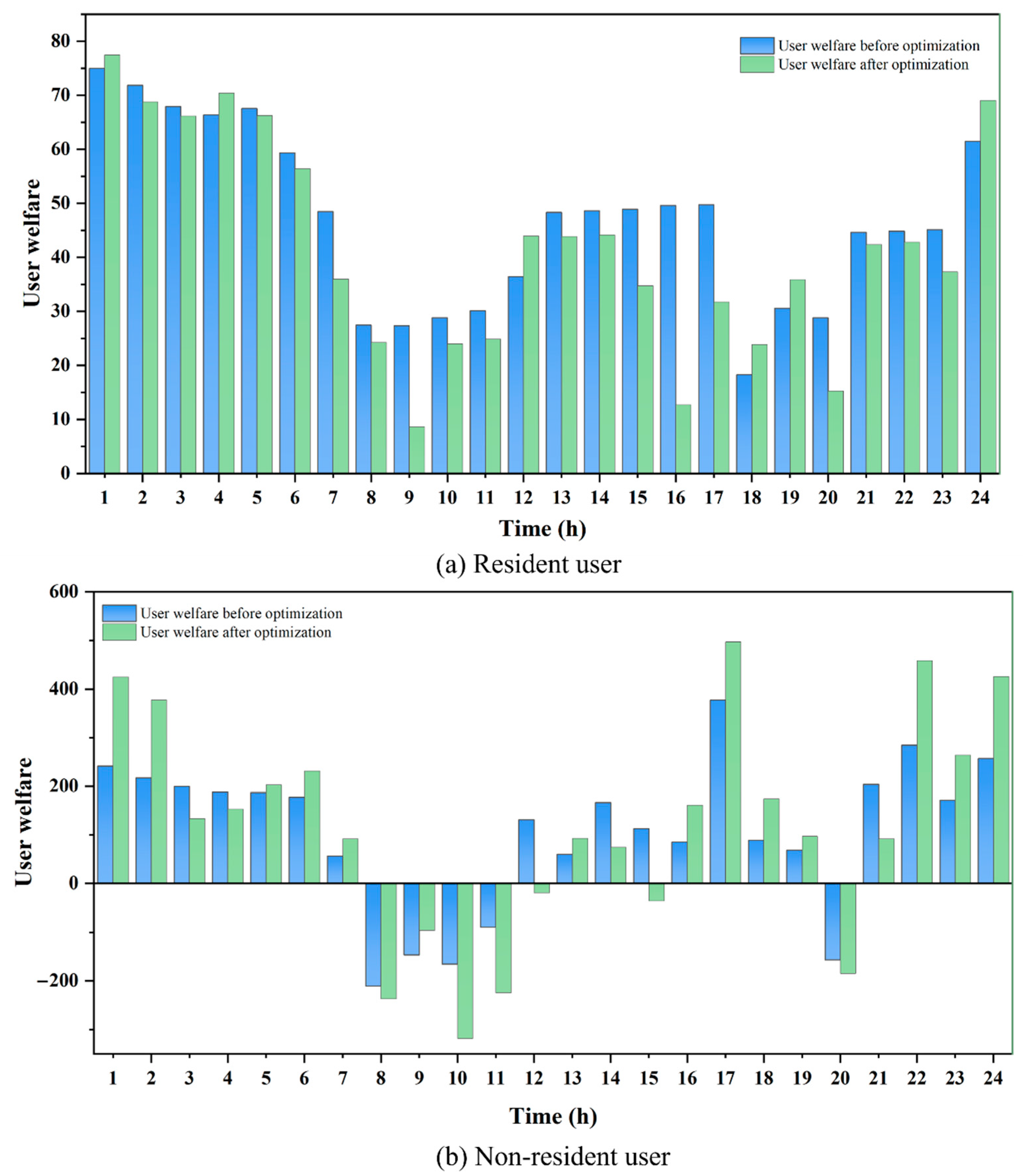

The gas purchase costs, utility, and welfare for residential users are presented in

Table 6. Although the optimized user utility is 10.87 lower than before, the amount spent on gas purchase has decreased by 63.15 CNY. According to Equation (24), the total user welfare is 52.28 units higher than the welfare prior to optimization. The corresponding hourly changes in user welfare are illustrated in

Figure 9a. The results indicate that the gas demand of residential users is relatively inelastic, and dynamic price adjustments do not significantly affect the basic living needs of residents. As a result, there may be a certain decline in user convenience, and the variation in user utility exhibits volatility in response to price adjustments. During peak periods, due to higher natural gas prices, the total user welfare decreases, whereas during low-price periods, user welfare increases. Overall, due to the significant reduction in gas purchase costs outweighing the loss in user utility, residential users benefit economically, thereby enhancing the overall level of gas consumption welfare.

The gas purchase costs, utility, and welfare for non-residential users are presented in

Table 7. Overall, the decline in user utility alongside an increase in user welfare indicates that the savings in gas purchase costs significantly outweigh the loss in utility. As a result, the final user welfare has significantly improved, increasing by 2224.01 compared to the pre-optimization scenario. This trade-off between utility and cost is particularly pronounced among non-residential users. The corresponding hourly variation in user welfare is shown in

Figure 9b. It can be observed that during valley periods, the welfare of non-residential gas users increases significantly, whereas it declines during flat and peak periods. However, since the magnitude of the increase during valley periods exceeds the decrease observed during flat and peak periods, the total welfare exhibits an upward trend over the scheduling cycle. The results indicate that, due to the higher gas consumption elasticity of non-residential users, adjusting production schedules in response to price signals during valley periods can significantly enhance user welfare.

It is noteworthy that the results in

Table 6 and

Table 7 show a much higher welfare increase for non-residential users (88.87%) compared with residential users (4.64%). This difference clearly reflects the gap in response capability and adjustment potential between residential and non-residential users under price signals. Residential users mainly use natural gas to meet basic daily needs, and their gas consumption behavior is relatively inelastic. Non-residential users possess greater scheduling flexibility over time, enabling them to shift energy-intensive processes to the valley period when gas prices are lower by adjusting production plans or process arrangements, thereby significantly reducing gas costs. Therefore, the reduction in gas costs for non-residential users is much greater than the slight decrease in their utility, resulting in a significant net welfare gain. These findings indicate that under price-based demand response mechanisms, consumers with greater temporal flexibility and load elasticity can achieve higher economic welfare gains through optimized gas usage scheduling and cost management.

The scheduling optimization not only effectively reduces the operating costs of gas suppliers but also significantly enhances user welfare, thereby achieving a win-win scenario for both gas suppliers and users. In addition to notable economic benefits, the dynamic pricing mechanism, when integrated with carbon emission constraints and carbon trading schemes, demonstrates differentiated environmental impacts across various user groups. This study proposes differentiated carbon emission management strategies for different types of users. Residential users, due to their relatively low gas consumption and non-participation in carbon trading, have their carbon emissions calculated and constraints set within the model. In contrast, non-residential users, characterized by higher gas consumption and the involvement of certain industrial users in carbon trading, require the incorporation of a ladder-type carbon trading cost structure. This strategy aligns with the practical conditions of future natural gas markets and provides theoretical support for the differentiated management of carbon emissions among various gas consumers.

Table 8 presents the changes in natural gas carbon emissions and carbon trading costs for residential and non-residential users before and after the scheduling optimization. The corresponding changes in hourly carbon emissions before and after optimization are shown in

Figure 10. The results indicate that residential users have a relatively small baseline gas consumption and do not directly participate in carbon trading. Under dynamic pricing and carbon emission constraints, their emissions decrease from 3349.16 kg to 3233.98 kg, representing a reduction of 115.18 kg or approximately 3.44 percent. This suggests that through effective scheduling optimization, significant reductions in carbon emissions can be achieved for residential users. For non-residential users, the baseline gas consumption and associated emissions are significantly higher, and some industrial users bear tiered carbon trading costs. Under the combined effect of dynamic pricing and carbon trading, their carbon emissions decrease from 31,650.49 kg to 29,493.69 kg, representing a reduction of 2156.8 kg or about 6.82 percent. At the same time, the carbon trading cost declines from 2035.57 CNY to 1851.72 CNY, a reduction of 183.85 CNY. This indicates that the LTCTM not only contributes to reducing carbon emissions from non-residential users but also effectively controls their carbon trading costs, thereby managing the overall carbon emissions of the system. In summary, residential users, as low-demand consumers, primarily contribute to relative emission reduction and the stabilization of carbon emission fluctuations. Non-residential users, as high-demand consumers, play a leading role in total emission reduction and the decline of carbon trading costs. The differentiated responses of the two user groups enable the system to balance stability and aggregate emission reduction, thereby supporting the long-term reliable operation of natural gas scheduling.

4.3. Analysis of System Benefits Under Different Price Signal Guidance

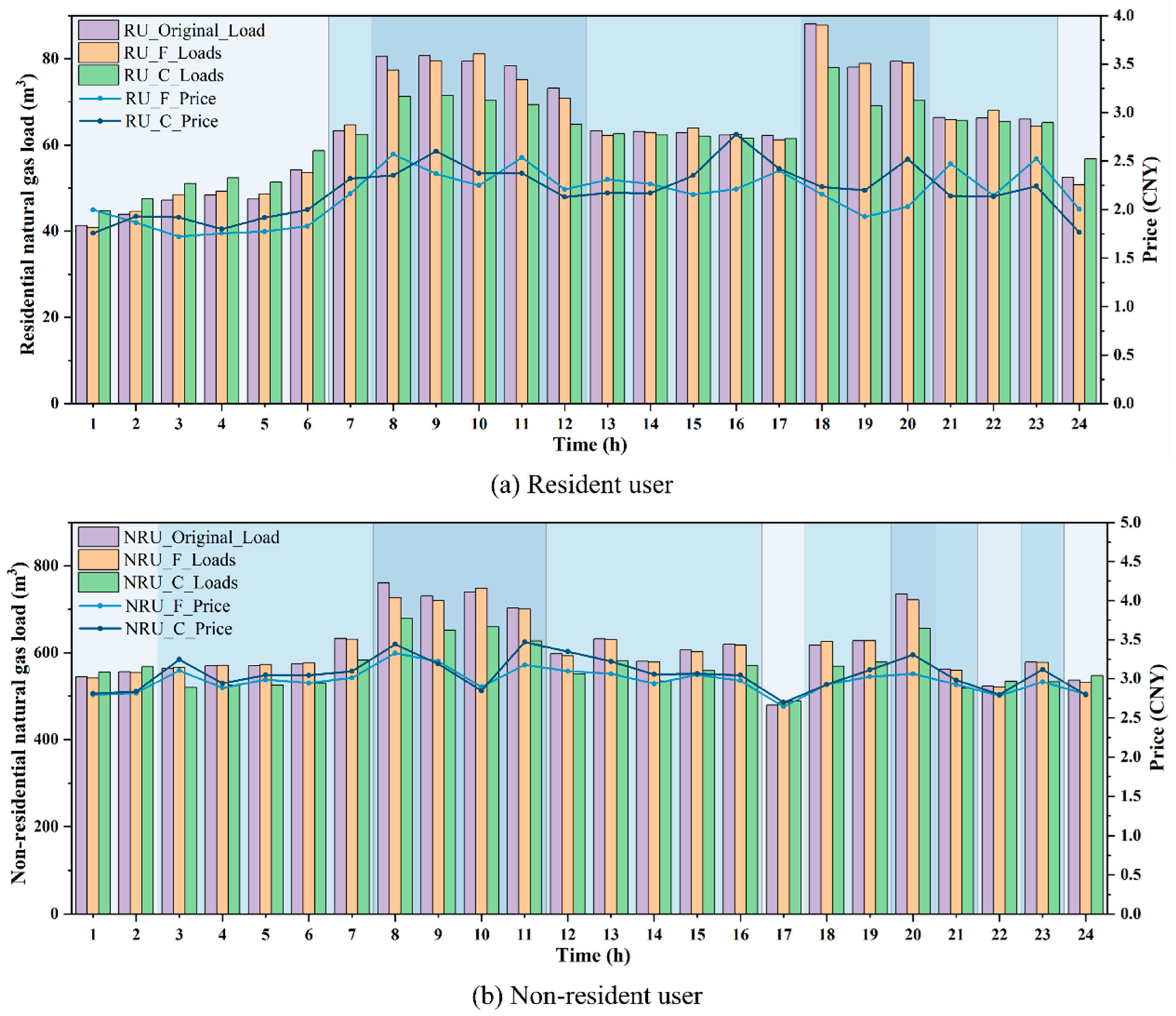

To further examine the model’s sensitivity and robustness under different price elasticity settings, and to assess the role of time-of-use price elasticity in regulating natural gas prices, guiding user load reduction and shifting, and mitigating peak-valley load differences, this section designs several comparative scenarios with varying elasticity settings. As shown in

Table 9, four scenarios are set, with RU_F and RU_C representing the scheduling scenarios resulting from changes in residential user gas demand due to price fluctuations under fixed price elasticity and time-of-use price elasticity. Similarly, NRU_F and NRU_C represent the scheduling scenarios after the variation in gas demand from non-residential users due to price changes under fixed price elasticity and time-of-use price elasticity. In this context, the fixed price elasticity for users is based on their own price elasticity, with residential users and non-residential users having values of −0.233 and −0.239 [

38,

40]. The time-of-use price elasticity follows the values presented in

Table 3.

Figure 11 compares the load variations and dynamic price adjustments for residential and non-residential users, contrasting the effects of fixed price elasticity with those of time-of-use price elasticity. RU_Original_Load and NRU_Original_Load refer to the original natural gas load for residential users and non-residential users. It can be observed that although the RU_F scenario induces a slight increase in gas consumption during valley and flat periods, and a slight decrease during peak periods, the overall guiding effect is not significant. This is due to the inability of price adjustments to meet users’ psychological expectations, resulting in reverse fluctuations at specific time points (for example, a decrease in gas consumption at 1:00 and 24:00, and an increase in consumption at 10:00 and 19:00). The RU_C scenario can effectively guide users to increase their gas consumption during valley and flat periods, while reducing consumption during peak periods, thereby alleviating the scheduling pressure during peak times. In the NRU_F scenario, the guiding effect of the valley and flat periods is not significant, manifesting only as slight variations in gas consumption. During peak periods, gas consumption decreases, but at certain time points (e.g., 10:00), there is a slight increase in consumption, indicating that the regulatory effect of this scenario on user gas consumption behavior is not pronounced. In the NRU_C scenario, the gas consumption during valley hours significantly increases, while the gas consumption during flat and peak hours notably decreases. Therefore, the dynamic pricing determined by the fixed price elasticity has a limited effect on guiding users’ gas consumption behavior, and certain nodes are prone to fluctuations. The dynamic pricing determined by time-of-use price elasticity exhibits significant effectiveness in load management, effectively shifting and reducing natural gas load. Dynamic pricing, developed based on time-of-use price elasticity, can effectively shift and reduce natural gas load. It ensures safer and more stable scheduling during peak periods, thereby preventing the system from experiencing excessive pressure.

Table 10 and

Table 11 present the economic benefits of the gas supplier and users during the scheduling process under different scenarios. For the gas supplier, the purchasing costs, distribution costs, and compressor operation costs in the RU_C scenario are lower than those in the RU_F scenario, while the revenue in the RU_C scenario is higher than that in the RU_F scenario. Similarly, in the gas scheduling for non-residential users, NRU_C also demonstrates lower costs and higher benefits. In terms of user benefits (as shown in

Table 11), the user welfare in the RU_C scenario is slightly higher than that in the RU_F scenario, while the user welfare in the NRU_C scenario exceeds that in the NRU_F scenario by 772.67. The results indicate that, under the influence of the time-of-use price elasticity matrix, the cost for gas suppliers is reduced, and their revenue is enhanced. At the same time, the welfare of both residential and non-residential users is improved, thereby enabling the realization of a more economically efficient scheduling solution.

Additionally,

Table 12 presents the carbon emissions, carbon trading costs, and load volatility of users under different scenarios. The carbon emissions in the RU_C scenario are 98.7 kg lower than those in the RU_F scenario. In the NRU_C scenario, carbon emissions are reduced by 1678.61 kg compared to the NRU_F scenario, resulting in a savings of 171.67 CNY in carbon trading costs. This indicates that the dynamic pricing strategy derived from time-of-use price elasticity outperforms the fixed price elasticity in terms of environmental benefits. Additionally, the load variation induced by the RU_C scenario results in a reduction in the volatility from the original value of 0.2059 to 0.1333. In contrast, the volatility for RU_F decreases only to 0.2006, indicating a relatively limited adjustment effect. The NRU_C scenario reduces the load volatility from the original value of 0.1221 to 0.0899. In contrast, the NRU_F scenario only adjusts it to 0.1166, with the adjustment effect being less pronounced. It is evident that time-of-use dynamic pricing performs better than fixed pricing in reducing load volatility and lowering carbon emissions. For both residential and non-residential gas scheduling, dynamic price signals derived from price elasticity are more effective than fixed-price elasticity in guiding gas consumption behavior and regulating gas volume, thereby mitigating load variability. In addition, the environmental benefits and load volatility effects of time-of-use dynamic pricing show heterogeneous patterns between residential and non-residential users. Non-residential users achieve greater emission reductions and carbon trading cost savings because of larger gas consumption, flexible production schedules, and stronger exposure to carbon cost constraints. In contrast, residential users exhibit more pronounced improvements in load smoothing, yet their emission reductions remain limited due to the rigidity of household energy demand. Therefore, the time-of-use dynamic pricing mechanism has potential to enhance system scheduling efficiency and to facilitate the implementation of energy-saving and emission-reduction policies.

4.4. Analysis of Load Guidance and User Utility Under Different Gas Consumption Behaviors

For gas suppliers, user gas consumption behavior directly affects load distribution as well as cost and revenue. A well-optimized gas procurement strategy can reduce procurement and transmission costs while maintaining the stability of gas distribution within the system. For end users, adjustments in gas consumption behavior influence gas usage costs and user welfare, contributing to the reduction in unnecessary waste. User gas consumption behavior is primarily influenced by user utility. Equation (11) incorporates price sensitivity and load variation acceptance into the utility function to characterize users’ responses to price signals and load adjustments. To analyze and verify the model’s sensitivity and user behavioral patterns under different combinations of

and

, this section adopts the residential gas load and relevant parameters from

Section 4.1 as fixed data. Four different parameter combinations representing gas consumption preferences are established, as shown in

Table 13.

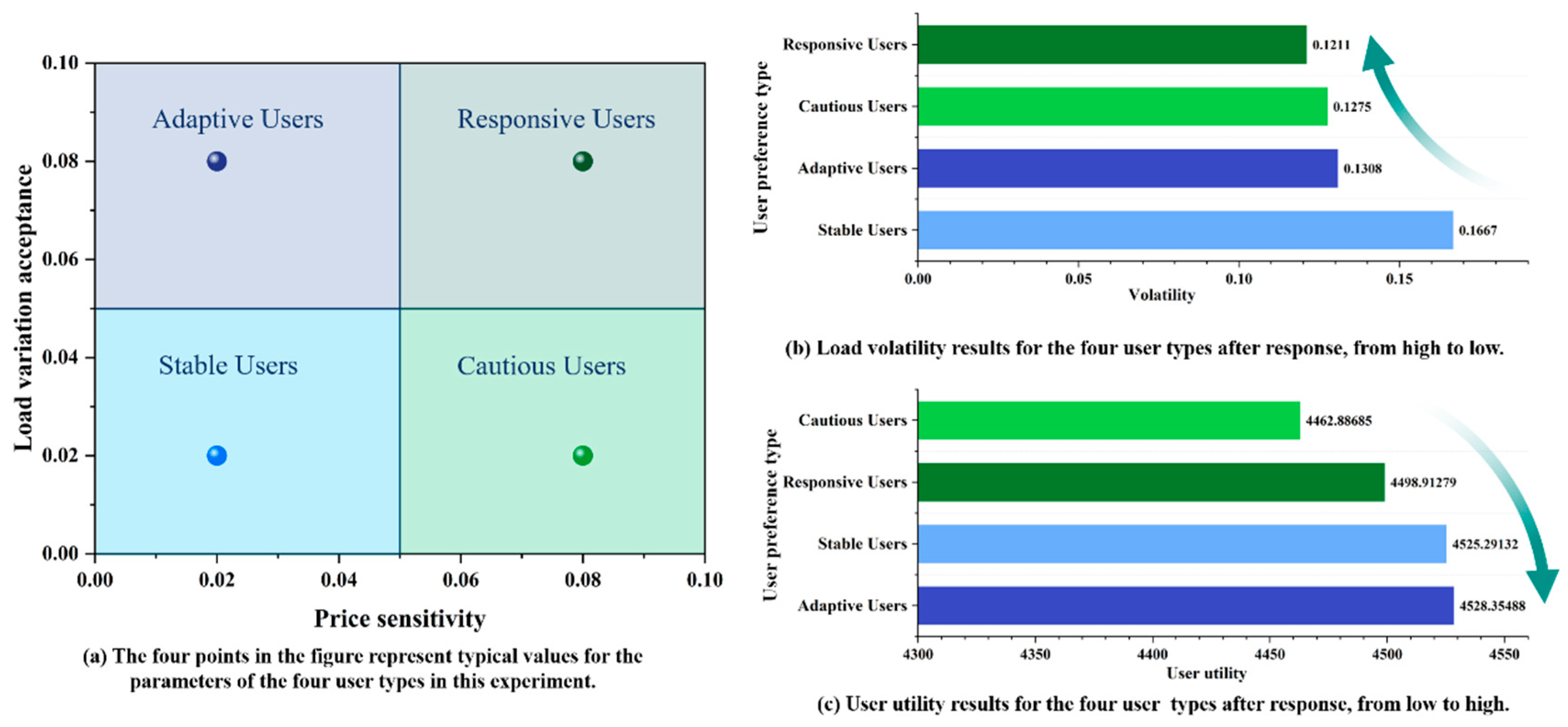

Figure 12a illustrates the interval settings of adaptive, stable, responsive, and cautious users in terms of price sensitivity and load variation acceptance. The median-proximal value within the interval is selected as the representative parameter. This approach preserves heterogeneity while avoiding extreme situations, thereby providing more representative input parameters for the simulation experiments. The [

,

] values for the four types are [0.02, 0.08] for adaptive users, [0.02, 0.02] for stable users, [0.08, 0.08] for responsive users, and [0.08, 0.02] for cautious users.

Figure 12b,c present the load volatility and utility rankings of the four user categories after scheduling optimization. The results indicate clear differences in performance. Stable users exhibit the highest volatility (0.1667) with a moderate utility level (4525.29132). Responsive users achieve the lowest volatility (0.1211) while maintaining relatively high utility (4498.91279). Cautious users perform poorly in both volatility (0.1275) and utility (4462.88685). Adaptive users strike a balance between utility (4523.35488) and volatility (0.1308), reflecting a more resilient response pattern.

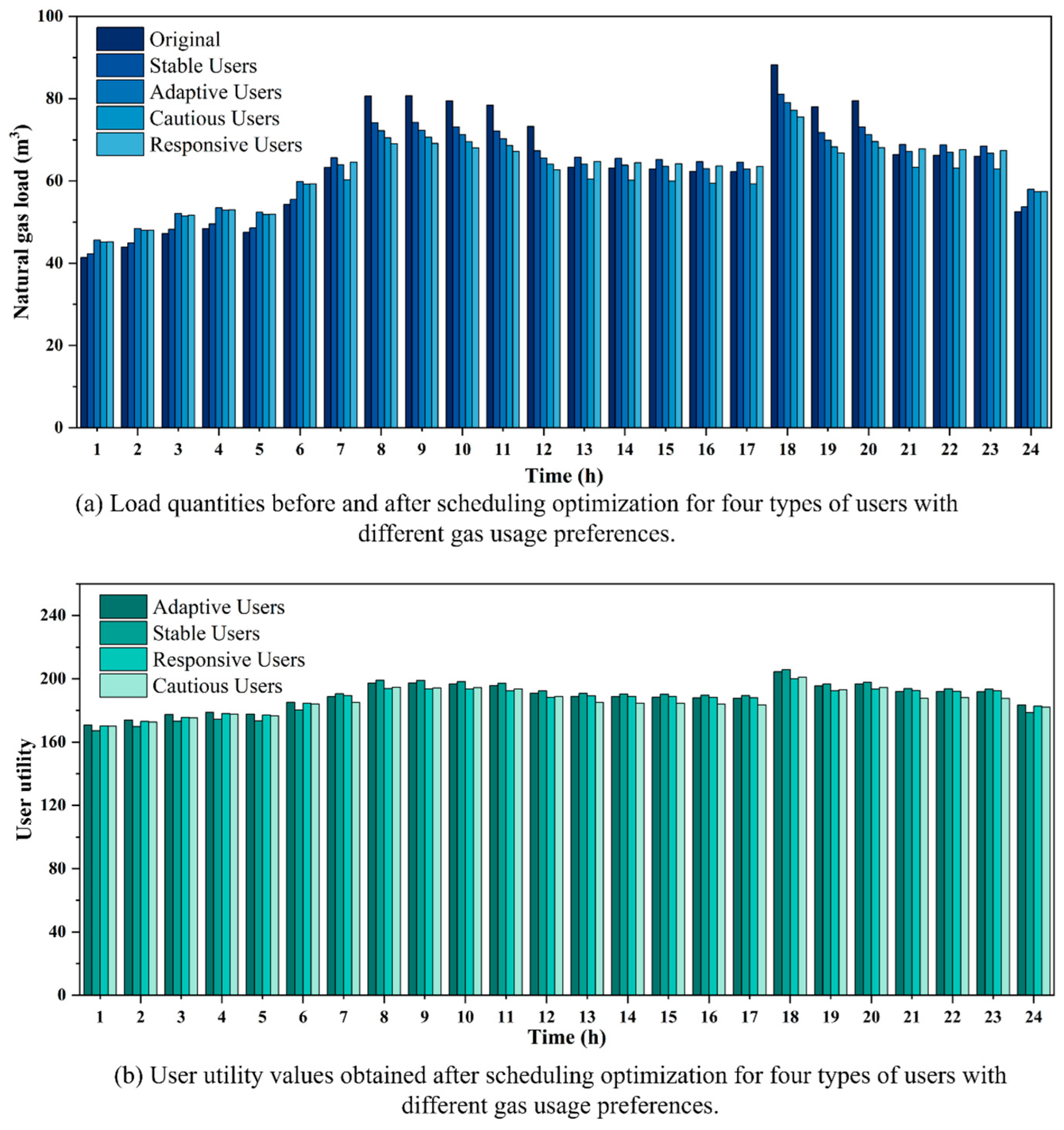

On the one hand, guiding users to adjust their required load through price signals to achieve peak shaving and valley filling contributes to enhancing the overall stability and security of the scheduling system. From the perspective of peak shaving and valley filling capabilities, responsive users exhibit high sensitivity to price changes, demonstrating the strongest load adjustment ability. Under price guidance, it is capable of flexibly adjusting the load fluctuations within the scheduling period to adapt to price changes. These users exhibit high values of

and

, enabling them to respond actively under dynamic pricing strategies, thereby providing significant flexibility for optimizing scheduling. Stable users, due to their insensitivity to price fluctuations, lack the motivation to adjust their load. Additionally, constrained by gas usage plans and practical conditions, their acceptance of load variations is relatively low. As a result, they tend to maintain a stable consumption pattern, demonstrating the weakest peak-shaving and valley-filling capabilities. The peak-shaving and valley-filling capacity of cautious users is second only to that of responsive users. Due to their higher value of

, they exhibit a stronger willingness to adjust their load. However, due to the constraints imposed by inflexible loads, the load regulation capability of such users is limited, necessitating a reduction in utility to accommodate load variations. Therefore, a trade-off must be made between economic benefits and gas usage stability. Although adaptive users exhibit strong load regulation capability, their relatively low

results in limited motivation for voluntary load adjustment. Adjustments are made moderately, with consideration for economic benefits, only when significant price changes occur. The details of load fluctuation of users with different gas consumption preferences in a scheduling period are shown in

Figure 13a.

On the other hand, when guiding users to adjust their gas consumption, their actual willingness must be considered. The utility values of the four user types are shown in

Figure 12c. The results indicate the following ranking of user utility values: Adaptive Users > Stable Users > Responsive Users > Cautious Users. Adaptive users exhibit low price sensitivity and significant load flexibility, enabling rational load adjustment while maintaining comfort levels. These users experience optimal outcomes under stable and fluctuating prices, resulting in the highest utility values. Stable users exhibit a weak response to price and load fluctuations, with their gas consumption patterns minimally affected by price variations, maintaining a consistent demand. Although lacking regulation capacity, such users maintain high psychological utility due to stable gas consumption. The utility of responsive users is relatively low. Although they can actively respond to price adjustments and optimize costs through load regulation, their consumption patterns are significantly impacted, leading to additional adjustment costs and affecting comfort. As a result, their overall utility is lower than that of adaptive and stable users. Cautious users are sensitive to price changes, but due to their strong load rigidity, they are reluctant to accept significant load adjustments. These users accept load adjustments forcefully to reduce costs, sacrificing their own gas consumption experience, resulting in the lowest overall utility. The details of user utility with different gas consumption preferences in a scheduling period are shown in

Figure 13b.

4.5. The Effect of Different Decision-Making Mechanism Factors on Scheduling Strategy Selection

In the EW-VIKOR method, the decision-making factor

serves as a key parameter to represent preference in the evaluation process. It balances between minimizing the maximum regret, which reflects risk aversion, and maximizing the overall benefit, which reflects collective orientation. When

takes a smaller value, the model places greater emphasis on reducing the worst performance of individual objectives, thereby indicating a conservative decision-making attitude. When

takes a larger value, the model emphasizes the overall average level, reflecting a tendency toward risk preference or collective utility maximization. When

equals 0.5, the system exhibits a risk-neutral attitude [

41]. To evaluate the influence of

on the final optimal trade-off solution, this section conducts a fine-grained analysis of

within the range [0, 1] using a step size of 0.01. Sensitivity experiments are performed separately on the datasets of residential and non-residential users (as presented in

Section 4.1). The analysis compares the variations and practical implications of supplier cost, user welfare, carbon emissions, and load volatility under different values of

.

Figure 14a,b present the optimized load and price results for residential and non-residential users under different values of

. The results show that the load and price curves of residential users exhibit only minor variations across different decision-making factors

. This indicates that their adjustment potential is limited, while the outcomes remain robust. Non-residential users show higher sensitivity to

. A low

value leads to significant peak load reduction and is suitable for scenarios that emphasize system stability and security. A high

value results in weaker load reduction during certain peak periods, such as 10 h and 20 h, and focuses more on improving overall system efficiency. Also, the price level is higher in certain periods (such as 13 h, 19 h, and 23 h), which further encourages load shifting to other hours.

Table 14 and

Table 15 indicate that variations in the decision-making factor

under the EW-VIKOR method show clear differences between residential and non-residential users. For residential users, supplier cost, user welfare, carbon emissions, and volatility after demand response are all improved compared with the pre-response case. Within the interval [0.00, 0.82], the supplier cost decreases by 74.64 CNY, user welfare increases by 52.28, carbon emissions decrease by 115.18 kg, and volatility declines by 0.0726. When

increases to 0.83 or higher, the variations in economic and environmental benefits become minor, reflected only in slight fluctuations in user welfare and carbon emissions. Overall, the system performance remains at a favorable level. This indicates that the model results are robust to changes in

. Hence, for residential users, selecting a moderate decision-making factor, such as

= 0.5, achieves a balanced outcome in both economic efficiency and environmental performance, without excessive reliance on

adjustment.

Compared with residential users, non-residential users show more sensitive changes in economic and environmental benefits under different values of , which highlights distinct differences in decision-making preferences. When the value of is set within [0.00, 0.12], the system scheduling outcome shifts toward conservative objectives. The supplier cost decreases by 1745.56 CNY, while carbon emissions and carbon trading costs are reduced by 1979.9 kg and 170.47 CNY. The volatility declines by 0.0327. Meanwhile, user welfare significantly increases by 2236.06 under stable operating conditions. This outcome is suitable for scenarios where operational security and risk avoidance are prioritized. As increases to the ranges [0.13, 0.63] and [0.64, 0.93], the scheduling scheme shifts gradually toward overall benefit. Supplier costs and carbon emissions continue to decline, while user welfare rises further, reaching a peak of 4861.77. However, the volatility begins to increase. When approaches 1, the decision orientation clearly favors collective benefit maximization. The supplier cost reaches the minimum, user welfare attains the highest level, and both carbon emissions and carbon trading costs remain at their optimal values. However, the volatility decreases only by 0.016, indicating a limited improvement in system stability.

In summary, residential users achieve robust scheduling performance when the decision mechanism factor is set at the mid-range value (0.5). In contrast, the scheduling results of non-residential users are more sensitive to parameter settings. Strategies corresponding to smaller values favor system stability and fluctuation suppression. Strategies with larger values promote economic benefits and emission reduction targets. Therefore, applying the EW-VIKOR method to the Pareto solution set obtained from NSGA-III provides differentiated decision support for different user types and enables a flexible balance among economic performance, environmental outcomes, and system stability.