Information–Entropy Analysis of Stellar Evolutionary Stages with Application to FS CMa Objects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Observational Data on Stellar Properties

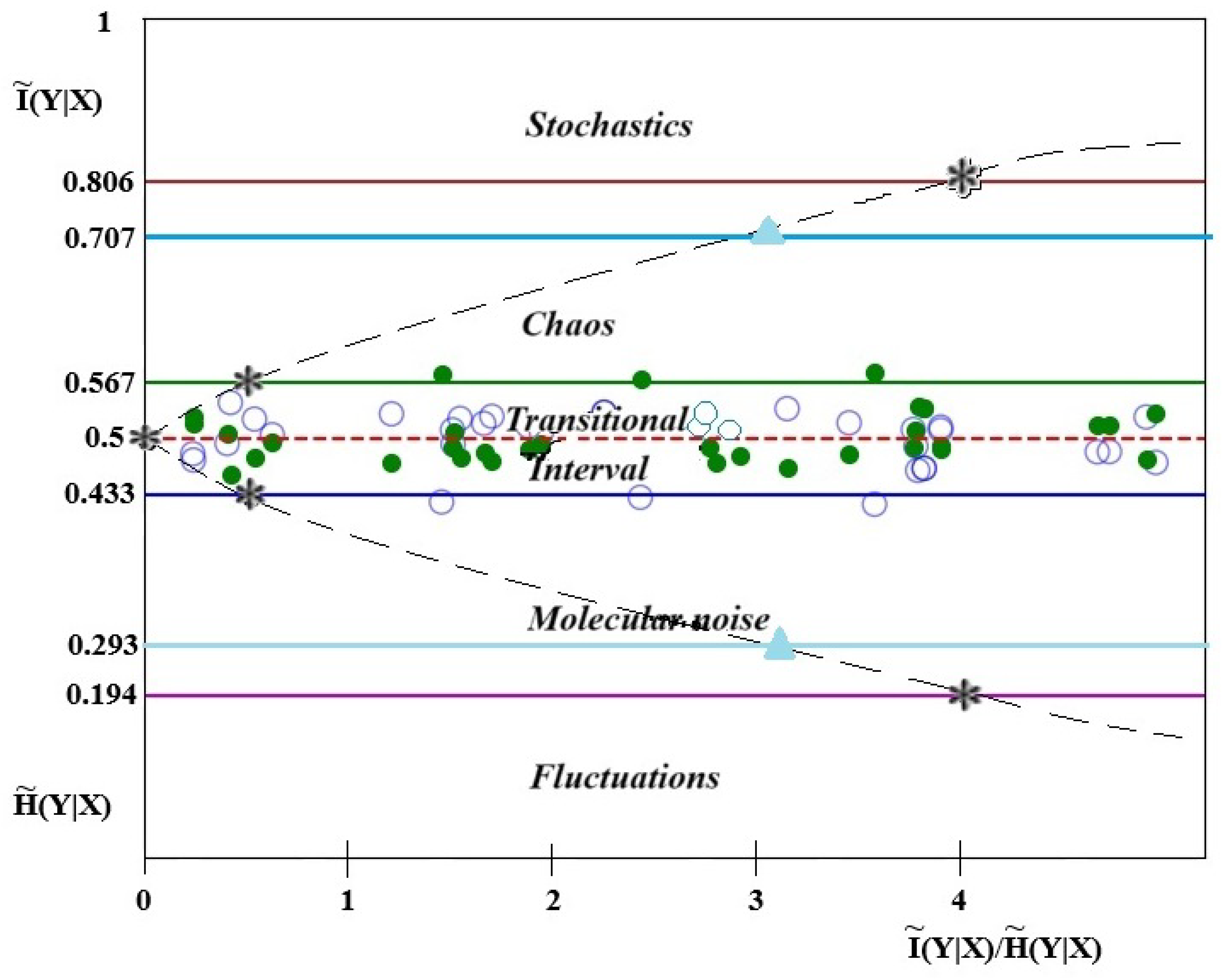

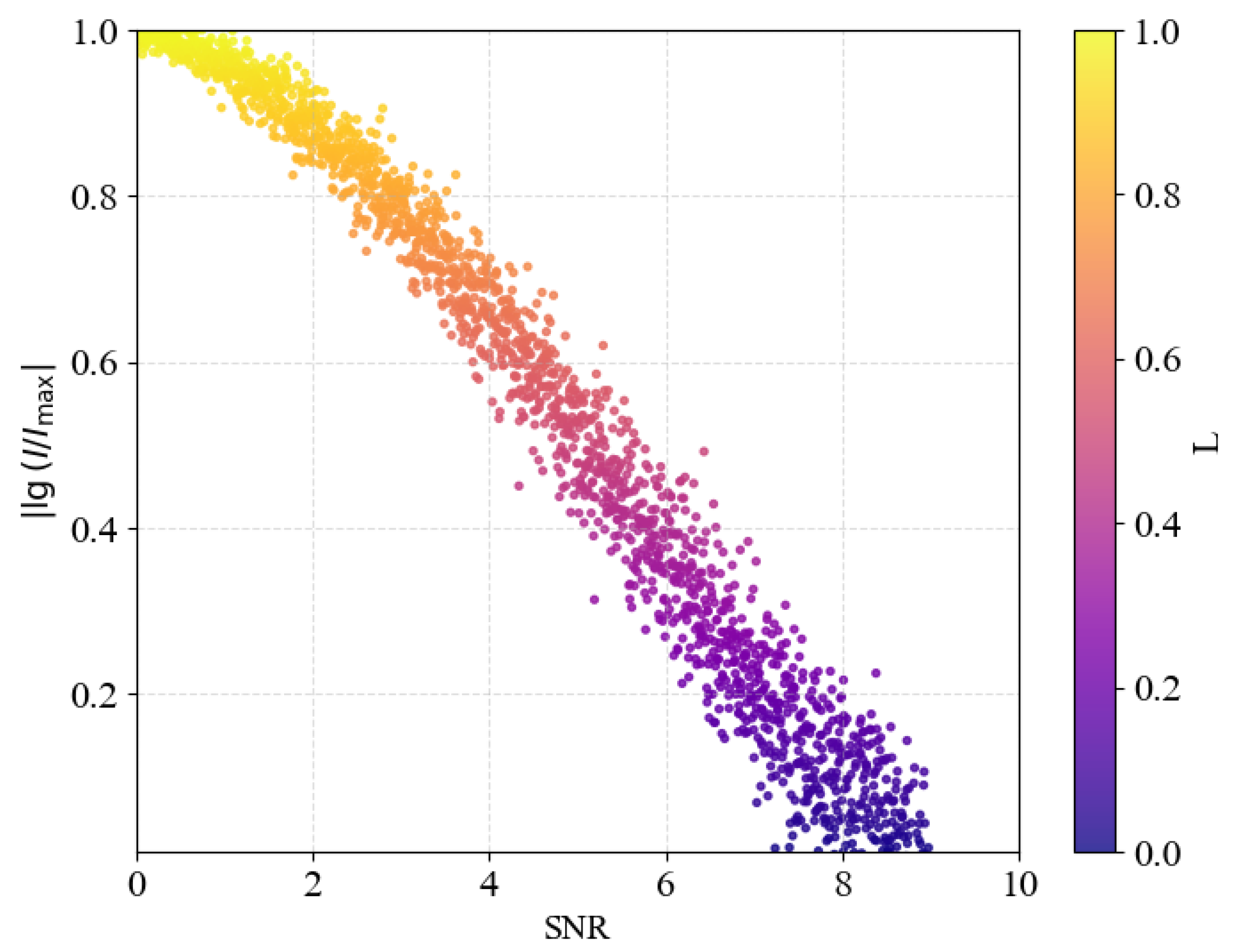

2.2. Information–Entropy Analysis

3. Main Results

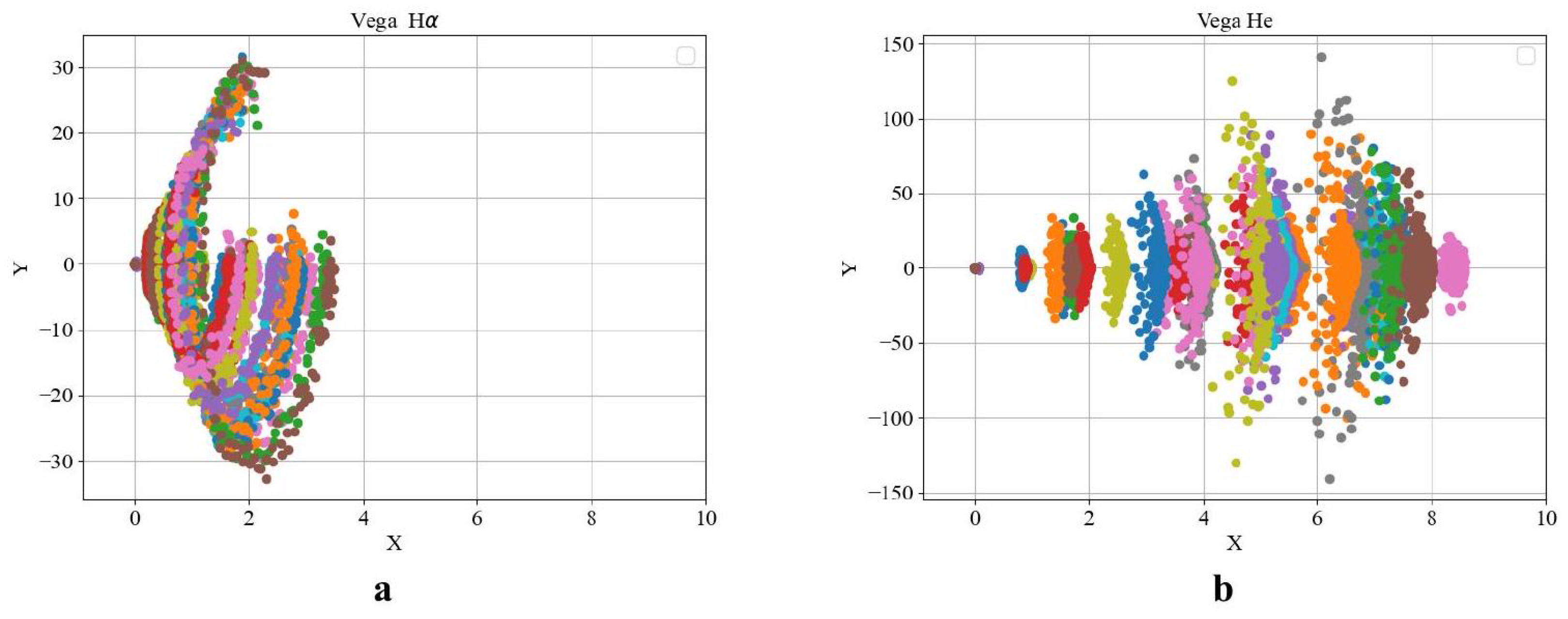

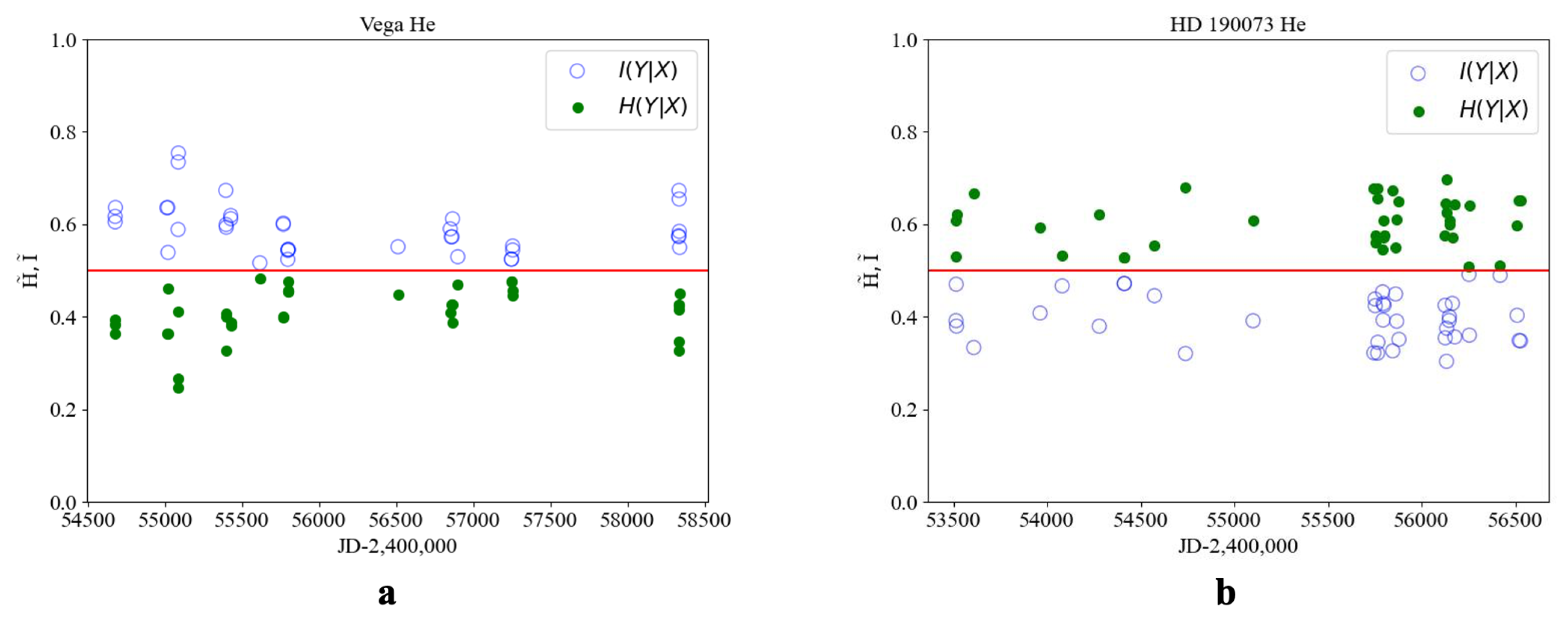

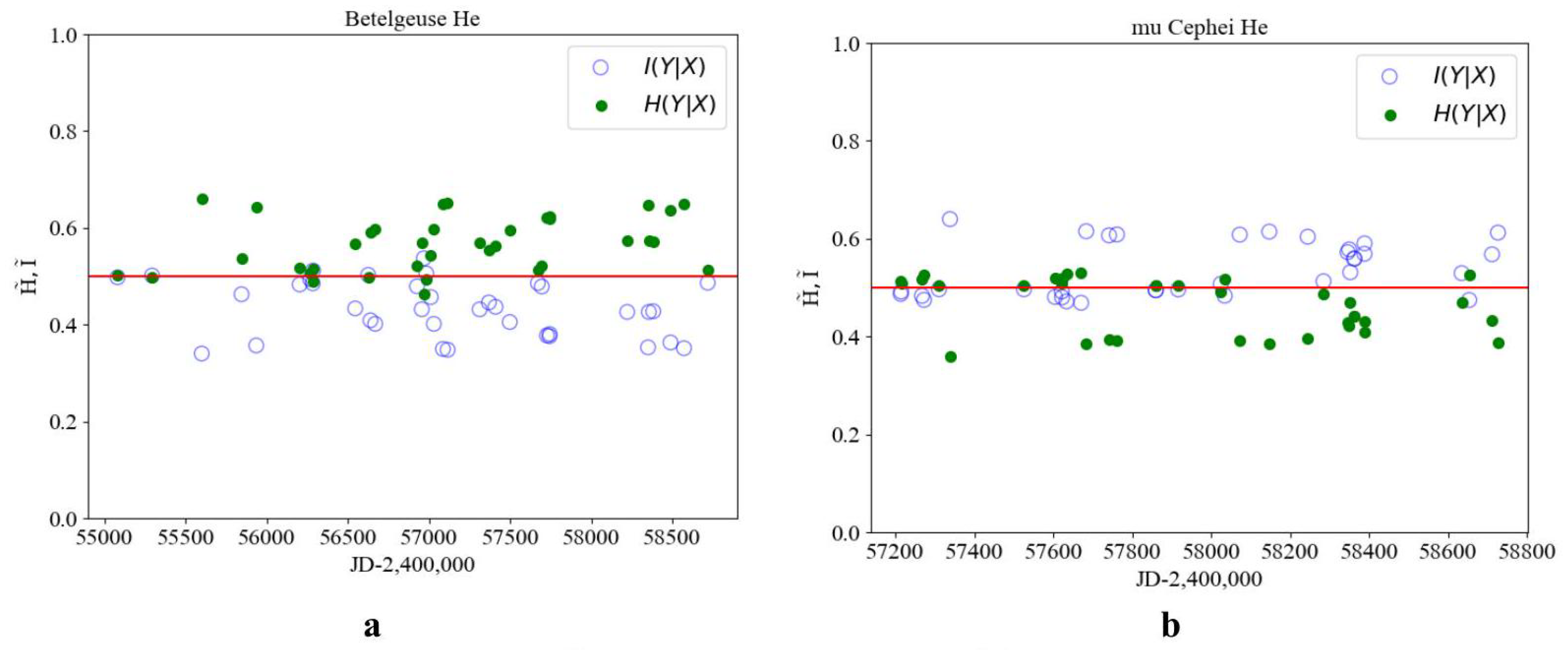

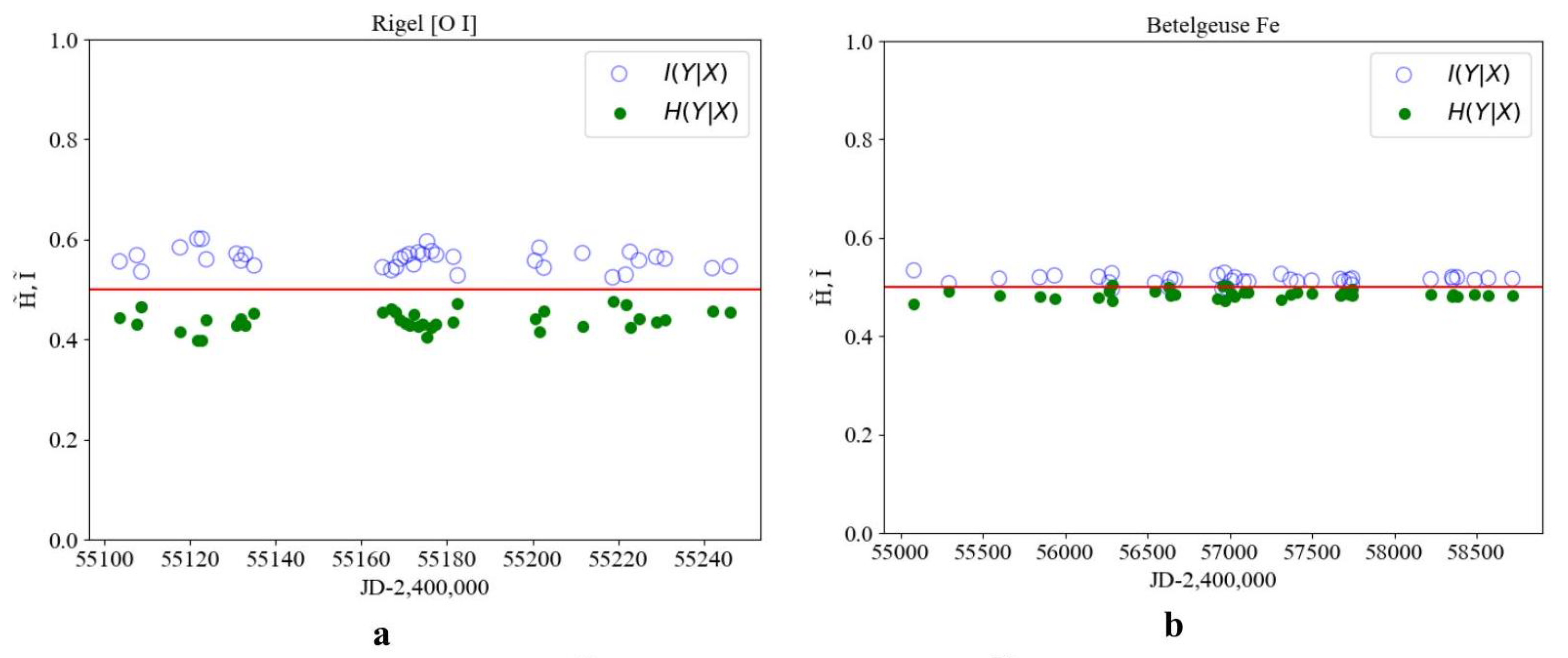

3.1. Results of Information–Entropy Analysis

3.2. Results of Information–Entropy Analysis of FS CMa Type Stars

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FS CMa | B[e]-type stars of the FS Canis Majoris type |

| PMS | Pre-Main Sequence |

| MS | Main Sequence |

References

- Johnstone, C.P.; Bartel, M.; Güdel, M. The active lives of stars: A complete description of the rotation and XUV evolution of F, G, K, and M dwarfs. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 649, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta, A.; Fontani, F.; Rivilla, V.M.; Mininni, C.; Colzi, L.; Sánchez-Monge, Á.; Beltrán, M.T. TEvolutionary study of complex organic molecules in high-mass star-forming regions. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.A.; Hillenbrand, L.A.; Feigelson, E.D.; Fowler, I.; Getman, K.V.; Broos, P.S.; Povich, M.S.; Gromadzki, M. The Effect of Molecular Cloud Properties on the Kinematics of Stars Formed in the Trifid Region. Astrophys. J. 2022, 937, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, F. Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction. Astron. Astrophys. 2007, 474, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagawa, H.; Haiman, Z.; Kocsis, B. Formation and evolution of compact-object binaries in AGN disks. Astrophys. J. 2020, 898, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.R.N.; Podsiadlowski, P.; Müller, B. Pre-supernova evolution, compact-object masses, and explosion properties of stripped binary stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 645, A5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graczyk, D.; Pietrzyński, G.; Thompson, I.B.; Gieren, W.; Zgirski, B.; Villanova, S.; Górski, M.; Wielgórski, P.; Karczmarek, P.; Narloch, W.; et al. A Distance determination to the Small Magellanic Cloud with an accuracy of better than two percent based on late-type eclipsing binary stars. Astrophys. J. 2020, 904, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenar, T.; Gilkis, A.; Vink, J.S.; Sana, H.; Sander, A.A.C. Why binary interaction does not necessarily dominate the formation of Wolf-Rayet stars at low metallicity. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 634, A79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, A.S. Toward understanding the B[e] phenomenon. I. Definition of the galactic FS CMa stars. Astrophys. J. 2007, 667, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, A.S.; Manset, N.; Kusakin, A.V.; Chentsov, E.L.; Klochkova, V.G.; Zharikov, S.V.; Gray, R.O.; Grankin, K.N.; Gandet, T.L.; Bjorkman, K.S.; et al. Toward understanding the B[e] phenomenon. II. New galactic FS CMa stars. Astrophys. J. 2007, 671, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, A.S.; Zharikov, S.V.; Manset, N.; Khokhlov, S.A.; Nodyarov, A.S.; Klochkova, V.G.; Danford, S.; Kuratova, A.K.; Mennickent, R.; Chojnowski, S.D.; et al. Recent Progress in Finding Binary Systems with the B[e] Phenomenon. Galaxies 2023, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomme, R.; Mahy, L.; Catala, C.; Cuypers, J.; Gosset, E.; Godart, M.; Montalban, J.; Ventura, P.; Rauw, G.; Morel, T.; et al. Variability in the CoRoT photometry of three hot O-type stars HD 46223, HD 46150 and HD 46966. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 533, A4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouret, J.-C.; Hillier, D.J.; Lanz, T.; Fullerton, A.W. Properties of Galactic early-type O-supergiants. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 544, A67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, J.F.; Veramendi, M.E. Dynamical structure of the multiple stellar system HD 164492. Bol. Asoc. Argent. Astron. 2016, 58, 105–107. [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko, A.; Matthews, J.M.; Aerts, C.; Pavlovski, K.; Pápics, P.I.; Zwintz, K.; Cameron, C.; Walker, G.A.H.; Kuschnig, R.; Degroote, P.; et al. Stellar modeling of Spica, a high-mass spectroscopic binary with a β Cep variable primary component. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 458, 1964–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieva, M.-F.; Przybilla, N. Present-day cosmic abundances. A comprehensive study of nearby early B-type stars and implications for stellar and Galactic evolution and interstellar dust models. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 539, A143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorec, J.; Cidale, L.; Arias, M.L.; Frémat, Y.; Muratore, M.F.; Torres, A.F.; Martayan, C. Fundamental parameters of B supergiants from the BCD system-I. Calibration of the (λ1, D) parameters into Teff. Astron. Astrophys. 2009, 501, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adigozalzade, H.N.; Bashirova, U.Z.; Ismailov, N.Z. Spectral variability of the Herbig Ae type star HD 179218. In Proceedings of the OBA Stars: Variability and Magnetic Fields, Online, 26–30 April 2021. Version v1. [Google Scholar]

- YKhan, M.; Castanheira, B.G. Astrophysical Properties of the Sirius Binary System Modeled with MESA. Astrophys. J. 2024, 977, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Monnier, J.D.; Kraus, S.; Bouquin, J.L.; Anugu, N.; Baron, F.; Brummelaar, T.T.; Davies, C.L.; Ennis, J.; Gardner, T.; et al. Imaging the inner astronomical unit of Herbig Be star HD 190073. Sol. Stellar Astrophys. 2023, 947, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, P.; Lignières, F.; Wade, G.A.; Aurière, M.; Böhm, T.; Bagnulo, S.; Dintrans, B.; Fumel, A.; Grunhut, J.; Lanoux, J.; et al. The rapid rotation and complex magnetic field geometry of Vega. Astron. Astrophys. 2010, 523, A41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkin, S.K.; Crawford, I.A. Spatially resolved optical spectroscopy of the Herbig Ae/Vega-like binary star HD 35187. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1998, 298, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, E.M.; Massey, P.; Olsen, K.A.G.; Plez, B.; Josselin, E.; Maeder, A.; Meynet, G. The effective temperature scale of galactic red supergiants: Cool, but not as cool as we thought. Astrophys. J. 2005, 628, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, G.; Claret, A.; Pavlovski, K.; Dotter, A. Capella (α Aurigae) revisited: New binary orbit, physical properties, and evolutionary state. Astrophys. J. 2015, 807, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, K.; Reffert, S.; Stock, S.; Trifonov, T.; Quirrenbach, A. Precise radial velocities of giant stars XII. Evidence against the proposed planet Aldebaran b. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 625, A22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, D.; Matsunaga, N.; Jian, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Fukue, K.; Hamano, S.; Ikeda, Y.; Kawakita, H.; Kondo, S.; Otsubo, S.; et al. Effective temperatures of red supergiants estimated from line-depth ratios of iron lines in the YJ bands, 0.97–1.32 μm. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 502, 4210–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maíz Apellániz, J.; Barbá, R.H.; Fariña, C.; Sota, A.; Pantaleoni González, M.; Holgado, G.; Negueruela, I.; Simón-Díaz, S. Lucky spectroscopy, an equivalent technique to lucky imaging-II. Spatially resolved intermediate-resolution blue-violet spectroscopy of 19 close massive binaries using the William Herschel Telescope. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 646, A11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.M.; Brown, A.; Guinan, E.F.; O’Gorman, E.; Richards, A.M.S.; Kervella, P.; Decin, L. An Updated 2017 Astrometric Solution for Betelgeuse. Astron. J. 2017, 154, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubimkov, L.S.; Lambert, D.L.; Rostopchin, S.I.; Rachkovskaya, T.M.; Poklad, D.B. Accurate fundamental parameters for A-, F- and G-type Supergiants in the solar neighborhood. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2010, 402, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsatti, A.M. The Puppis region and the last crusade for faint OB stars. Astron. J. 1992, 104, 590–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodyarov, A.S.; Miroshnichenko, A.S.; Khokhlov, S.A.; Zharikov, S.V.; Manset, N.; Klochkova, V.G.; Grankin, K.N.; Arkharov, A.A.; Efimova, N.; Klimanov, S.; et al. Toward Understanding the B[e] Phenomenon. IX. Nature and Binarity of MWC 645. Astrophys. J. 2022, 936, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, A.S.; Zharikov, S.V.; Danford, S.; Manset, N.; Korčáková, D.; Kříček, R.; Šlechta, M.; Omarov, C.T.; Kusakin, A.V.; Kuratov, K.S.; et al. Toward understanding the B[e] phenomenon. V. Nature and spectral variations of the MWC 728 binary system. Astrophys. J. 2015, 809, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condori, C.A.H.; Fernandes, M.B.; Kraus, M.; Panoglou, D.; Guerrero, C.A. The study of unclassified B[e] stars and candidates in the Galaxy and Magellanic Clouds. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2019, 448, 1090–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroshnichenko, A.S.; Danford, S.; Zharikov, S.V.; Klochkova, V.G.; Chentsov, E.L.; Vanbeveren, D.; Zakhozhay, O.V.; Manset, N.; Pogodin, M.A.; Omarov, C.T.; et al. Properties of Galactic B[e] Supergiants. V. 3 Pup–Constraining the Orbital Parameters and Modeling the Circumstellar Environments. Astrophys. J. 2020, 897, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, P.; Louge, T.; Théado, S.; Paletou, F.; Manset, N.; Morin, J.; Marsden, S.C.; Jeffers, S.V. PolarBase: A database of high-resolution spectropolarimetric stellar observations. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2014, 126, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, J.C. The potential of Shannon entropy to find the large separation of δ Scuti stars: The entropy spectrum. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 2022, 9, 953231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanabaev, Z.Z.; Ussipov, N.M. Information-entropy method for detecting gravitational wave signals. Eurasian Phys. Tech. J. 2023, 20, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhanabaev, Z.Z.; Grevtseva, T.Y. Physical fractal phenomena in nanostructured semiconductors. Rev. Theor. Sci. 2014, 2, 211–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalensky, A.E.; Yrkin, M.A. A point electric dipole: From basic optical properties to the fluctuation-dissipation theorem. Rev. Phys. 2021, 6, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anishchenko, V.S.; Astakhov, V.; Vadivasova, T.; Neiman, A.; Schimansky-Geier, L. Nonlinear Dynamics of Chaotic and Stochastic Systems; Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miroshnichenko, A.S. Toward Understanding the Origin of the B[e] phenomenon in FS CMa Type Objects. Commun. Byurakan Astrophys. Obs. 2018, 65, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kippenhahn, R.; Weigert, A.; Weiss, A. Stellar Structure and Evolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; p. 604. ISBN 978-3-642-30304-3. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Names of Stars | Temperature | Weight | Spectral Class | Evolutionary Status of a Star | Lit. Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HD46223 | 45,316 K | O4V | I | [12] | |

| 2 | HD46150 | 43,181 K | O5V | I | [12] | |

| 3 | HD210839 | 36,000 K | O | I | [13] | |

| 4 | HD164492 | 33,600 K | O7V | I | [14] | |

| 5 | Cephei ( Cephei) | 27,000 K | B2III | II | [15] | |

| 6 | Spica ( Vir) primary | 25,300 ± 500 | B1V | II and III | [16] | |

| 7 | Rigel (bet Ori) | 12,130 ± 530 | B8Ia | II | [17] | |

| 8 | HD179218 | 10,400 ± 600 | B9 | I | [18] | |

| 9 | (Sirius) | 10,500 K | A0m | II | [19] | |

| 10 | HD190073 | A2e | II | [20] | ||

| 11 | Vega ( Lyrae) | A0V | II and III | [21] | ||

| 12 | HD35187 | 8000 K | A7V | II | [22] | |

| 13 | Cyg ( Cygni) | 5790 K | F8 lab | II | [23] | |

| 14 | Aur (a Capella) | 4940 K | K0III | II | [24] | |

| 15 | Aldebaran | 4300 K | K5 III | II and III | [25] | |

| 16 | M() Cephei | 3700 K | 40–50 | M2Ia | III | [26] |

| 17 | Sco ( Scorpii) | 3660 K | M1.5lab | III | [27] | |

| 18 | Betelgeuse ( Orionis) | 3500 K | 15–20 | M1-2 Ia | III | [28] |

| 19 | o Cet (Peace) | 2900 K | M7III | III | [29] | |

| 20 | CD-315070 | 12,500 ± 500 | B7-B8 | II | [30] | |

| 21 | MWC645 | 18,000 ± 2000 | B | III | [31] | |

| 22 | MWC728 | 14,000 ± 1000 | B5 | III | [32] | |

| 23 | BD+23 3183 | A0V | II | [33] | ||

| 24 | 3Pup | A2.7Ib | II | [34] |

| Evolutionary Status of a Star | Stars | |

|---|---|---|

| I | HD210839 | 0.894 |

| I | HD46223 | 0.927 |

| I | HD46150 | 0.921 |

| II | Rigel | 0.617 |

| II | HD35187 | 0.656 |

| II | HD164492 | 0.701 |

| II | Vega III | 0.597 |

| II | HD190073 | 0.649 |

| II | Aldebaran III | 0.650 |

| II | Vir ( Virginis) II | 0.653 |

| II | o Cet (Peace) | 0.652 |

| II | HD179218 | 0.649 |

| II | Cephei ( Cephei) | 0.648 |

| II | (Sirius) | 0.655 |

| II FS CMa | BD+23 3183 | 0.619 |

| II FS CMa | CD-315070 | 0.640 |

| III | Sco (Antares) | 0.382 |

| III | Aur ( Capella) | 0.503 |

| III | Betelgeuse | 0.538 |

| III | Cephei | 0.568 |

| III | Cyg ( Cygni) | 0.272 |

| III FS CMa | MWC728 | 0.567 |

| III FS CMa | 3Pup | 0.527 |

| III FS CMa | MWC645 | 0.478 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhanabaev, Z.; Akniyazova, A.; Ashimov, Y. Information–Entropy Analysis of Stellar Evolutionary Stages with Application to FS CMa Objects. Entropy 2025, 27, 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111106

Zhanabaev Z, Akniyazova A, Ashimov Y. Information–Entropy Analysis of Stellar Evolutionary Stages with Application to FS CMa Objects. Entropy. 2025; 27(11):1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111106

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhanabaev, Zeinulla, Aigerim Akniyazova, and Yeskendyr Ashimov. 2025. "Information–Entropy Analysis of Stellar Evolutionary Stages with Application to FS CMa Objects" Entropy 27, no. 11: 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111106

APA StyleZhanabaev, Z., Akniyazova, A., & Ashimov, Y. (2025). Information–Entropy Analysis of Stellar Evolutionary Stages with Application to FS CMa Objects. Entropy, 27(11), 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27111106