1. Introduction

Each pixel in a hyperspectral image (HSI) contains continuous spectral information, giving hyperspectral imaging techniques stronger object recognition capabilities than traditional RGB methods [

1]. In recent years, hyperspectral imaging has been widely applied in fields such as crop identification [

2], mineral exploration [

3], and environmental monitoring [

4]. Among the various tasks based on HSI processing, hyperspectral image classification (HSIC) is one of the core research directions [

5,

6,

7]. HSIC mainly predicts the category labels of different objects. Due to its significant practical application value, HSIC has always been a hot research topic in the field of remote sensing [

8,

9,

10].

Previously, supervised learning-based machine learning methods were applied to HSIC, such as the K Nearest-Neighbor algorithm (KNN) [

11] and the support vector machine (SVM) [

12]. However, these machine learning algorithms rely on manual feature extraction, making it difficult to automatically learn complex spectral and spatial features and weakening the ability to model spatial information. On the other hand, with the emergence of deep learning technology in recent years, the above problems have been effectively solved. Deep learning can automatically learn complex spectral features and spatial structures and mine deeper nonlinear relationships, thus achieving better results in HSIC, and it has therefore become the focus of many scholars in modern HSIC [

13,

14,

15].

In the research process of applying deep learning to HSIC, many convolutional neural network (CNN) models have been used due to their excellent ability for local feature extraction [

16]. A CNN can effectively capture the local spatial correlation in an image through a convolution operation. With the help of multi-layer convolution and pooling operations, it can gradually extract the abstract features from the low to the high level, showing outstanding advantages in the spatial feature processing of HSIs [

17,

18,

19]. At an early stage, Chen et al. [

20] used a regularized deep feature extraction (FE) method based on a CNN, which utilized multiple convolutional and pooling layers to extract nonlinear, discriminative, and invariant deep features of HSIs, effectively extracting spectral–spatial features of HSIs and avoiding the problem of overfitting. To solve the problems of excessive computational complexity in 3D-CNNs and the inability to fully utilize spectral information in 2D-CNNs, Roy et al. [

21] proposed the Hybrid Spectral Convolutional Neural Network (HybridSN), which makes use of the hybrid structures of 3D-CNNs and 2D-CNNs and balances the spectral–spatial feature extraction and computational efficiency by extracting the spectral–spatial features first and then refining the spatial features. Chen et al. [

22] proposed for the first time an auto-convolutional neural network (Auto-CNN) for HSIC, which utilizes one-dimensional auto-convolutional neural networks and three-dimensional auto-convolutional neural networks as spectral and spectral spatial classifiers, respectively, to solve the problem that manually designed deep learning architectures may not be able to adapt to a specific dataset.

Although CNNs have many advantages in HSIC, they still have limitations. Because the sensory field in the convolution limits the CNN, capturing long-distance dependencies and global context information in an HSI is difficult, and the processing of spectral features is relatively singular [

23]. Therefore, many scholars have focused on the Transformer model to overcome the shortcomings of CNN in HSIC. Hong et al. [

24] introduced the Transformer into HSIC for the first time and proposed a novel network called SpectralFormer. It uses neighboring bands in the HSI to learn spectral local sequence information. It generates group spectral embeddings, which are connected by cross-layer jumps to transfer class memory components, thus better mining spectral feature sequence attributes to reduce the loss of key information. In order to solve the problem of most deep learning-based HSIC methods destroying spectral information when extracting spatial features or only being able to extract sequential spectral features in short-range contexts, Ayas et al. [

25] proposed a network architecture called SpectralSWIN, which makes use of the proposed Swin-Spectral Module to extract spectral–spatial features by combining the sliding-window self-attention and grouped convolution of spectral dimensions to achieve the hierarchical extraction of spectral–spatial features. Simultaneously, in order to address the issues of excessive dimensionality, spectral information redundancy, and the difficulty of appropriately combining spatial and spectral information in HSI, including the failure of existing methods to utilize first-order derivatives and frequency domain information fully, Fu et al. [

26] proposed a Differential-Frequency Attention-based Band Selection Transformer (DFAST) architecture by using the DFASEmbeddings module containing a multi-branching structure, a 3D convolution, the spectral–spatial attention mechanism, and the cascade Transformer encoder. A Differential-Frequency Attention-based Band Selection Transformer (DFAST) architecture is proposed.

Although Transformers demonstrate remarkable advantages in capturing global dependencies for HSI, they still suffer from high computational overhead, particularly when handling long sequences, since the self-attention mechanism scales quadratically with sequence length [

27]. Recently, Mamba [

28], an emerging sequence modeling paradigm, has offered a new direction for HSIC research. Building on this, Sun et al. [

29] proposed the Hyperspectral Spatial Mamba (HyperSMamba) model, which integrates the Spatial Mamba (MS-Mamba) encoder with an Adaptive Fusion Attention Module (AFAttention). This design not only alleviates the quadratic complexity bottleneck of Transformer-based self-attention but also mitigates the excessive computational burden in prior Mamba-based approaches, which is caused by selective scanning strategies.

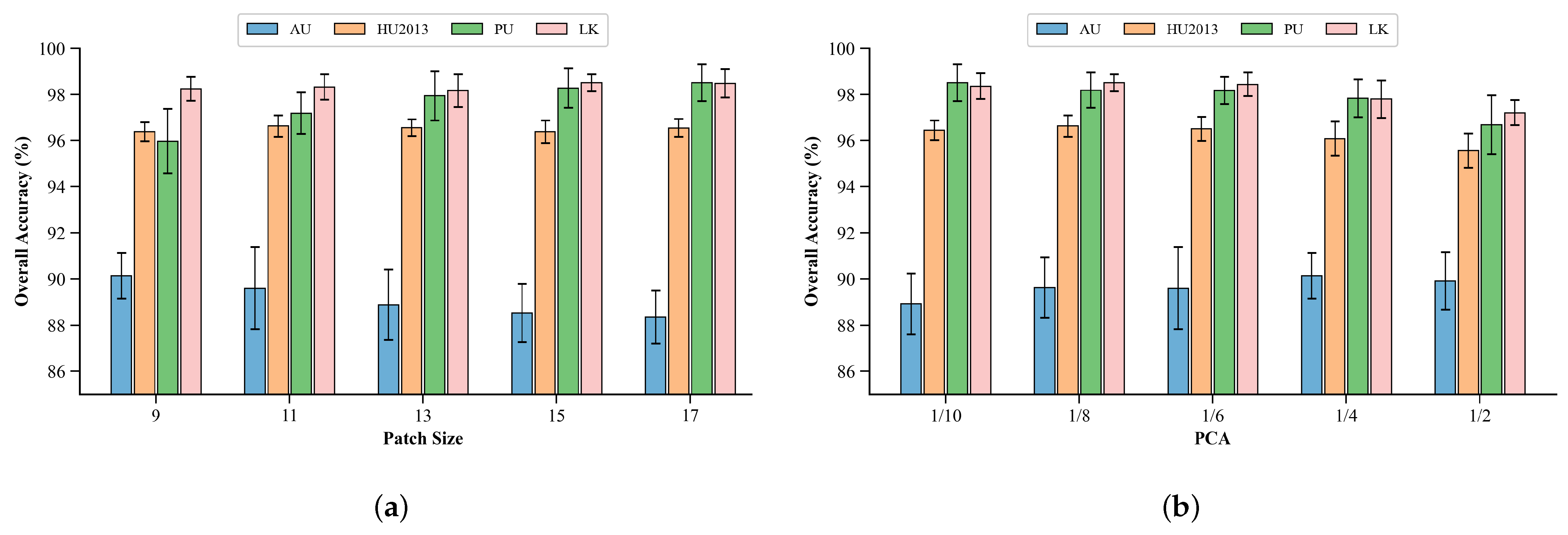

Although the Mamba model has improved computational complexity compared to the Transformer, we can see from the above models that the Mamba architecture is primarily based on the state space model (SSM) [

30,

31,

32]. However, Yu et al. [

33] found that SSM contains a significant amount of redundancy in image classification tasks, which negatively impacts classification accuracy. Therefore, they proposed the MambaOut model, which removes SSM from the model, significantly reducing the computational power required while improving performance. Additionally, we found that many deep learning models used for HSIC address the issue of excessive computational requirements by performing dimension reduction via principal component analysis (PCA) [

34]. However, this also poses the problem of partial spectral feature loss [

35].

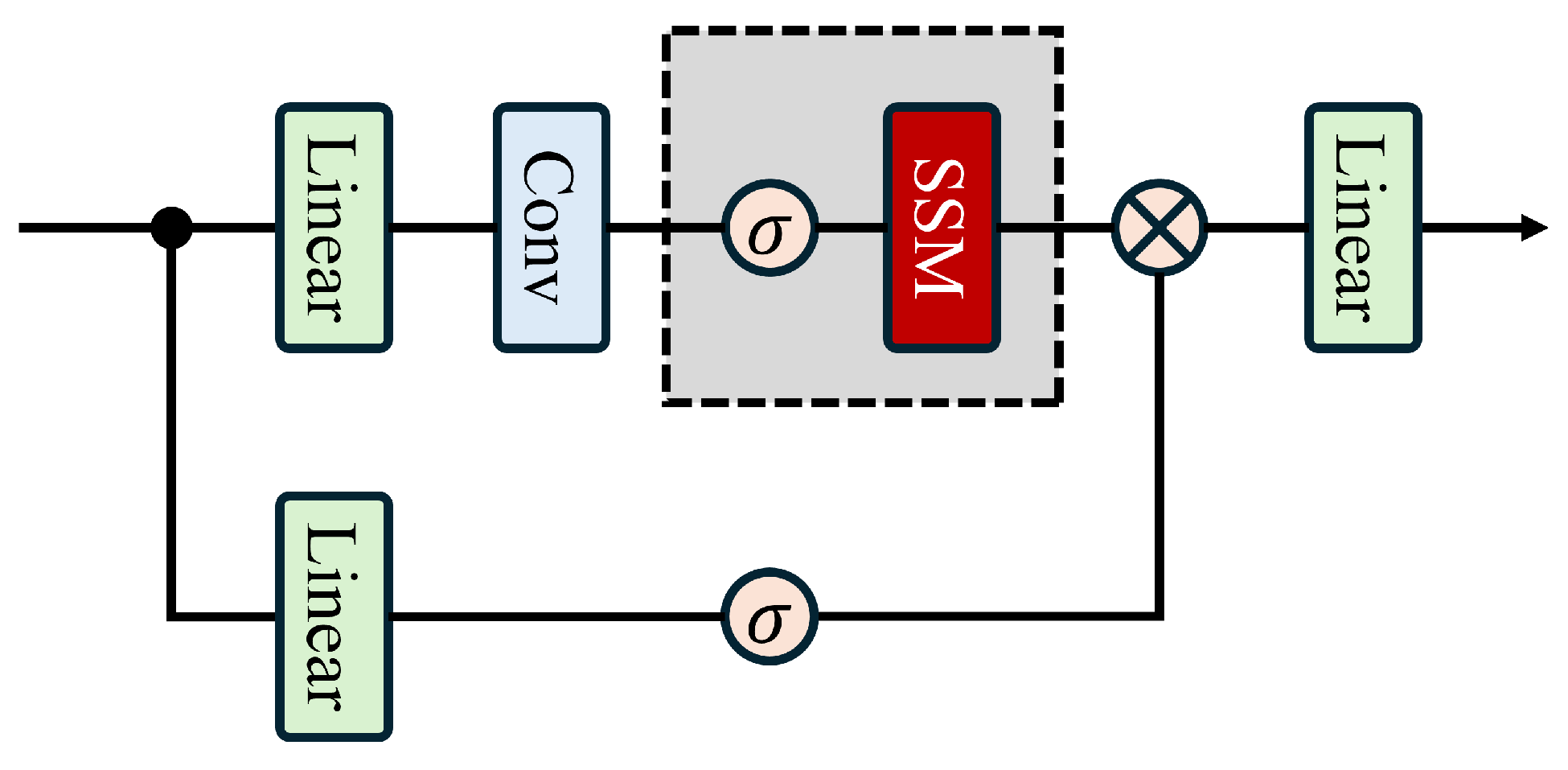

Therefore, to address the challenges in HSIC, we explored whether key spectral information could be extracted through independent modules after PCA dimensionality reduction to compensate for spectral information loss. Could a structure similar to Mamba be designed to achieve an efficient fusion of spectral and spatial features while enhancing computational efficiency? Thus, we propose the Spectral-Guided Fusion Network (SGFNet). Its core component is the Spectral-Guided Gated Convolutional Network (SGGC), which draws inspiration from the essence of the Mamba model while eliminating its redundant State Space Mechanism (SSM). To precisely capture the complex interplay between spectral and spatial information, we first process guiding spectral features through a Spectral-Aware Filtering Module (SAFM). This module encodes raw spectral sequences into a globally shared representation while amplifying critical spectral information. These spectral features are then fed into a redesigned Mamba architecture to compensate for key spectral information lost during PCA processing. To effectively fuse one-dimensional spectral features with two-dimensional spatial features, we introduce the Spectral–Spatial Adaptive Fusion (SSAF) module, enabling the efficient integration of spectral representations with global spatial representations. The fused features are applied to the gating mechanism of the SGGC, enabling spectral features to more effectively guide spatial feature extraction. Through rigorous comparative experiments, the proposed SGFNet demonstrates outstanding classification performance. In summary, our contributions include the following:

We propose SGFNet, which is an innovative spectral-guided MambaOut network for hyperspectral image classification (HSIC). From an information–theoretic perspective, hyperspectral data often exhibit high spectral redundancy, resulting in high entropy and making it challenging to extract discriminative features. SGFNet explores the feasibility of the MambaOut architecture in HSIC and demonstrates that the state–space mechanism (SSM) is not indispensable. By leveraging low-entropy spectral priors to guide spatial feature extraction, SGFNet enhances informative patterns while significantly reducing the number of parameters and FLOPs.

We design a Spectral-Aware Filtering Module (SAFM) that effectively suppresses redundant spectral responses while retaining informative spectral components. This process can reduce the entropy of raw hyperspectral data to provide reliable and high-information support for subsequent modules.

We propose the Spectral-Guided Gated CNN (SGGC), which is a Mamba-inspired structure without the SSM. Within SGGC, we introduce the Spectral–Spatial Adaptive Fusion (SSAF) module, which aggregates one-dimensional spectral features with two-dimensional spatial features and feeds the fused, low-entropy representations into the gating mechanism, effectively guiding spatial feature extraction with reduced uncertainty through spectral information.

We conducted rigorous and fair comparative experiments. The experimental results show that SGFNet achieved the highest overall accuracy (OA), average accuracy (AA), and Kappa coefficient when compared with eight state-of-the-art algorithms on four benchmark datasets. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of our entropy-aware design in improving HSIC performance.

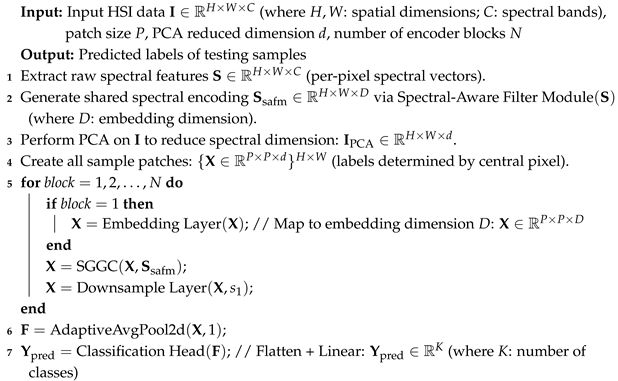

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, we introduce related work. In

Section 3, we describe in detail the various components of the proposed SGFNet. In

Section 4, we conduct detailed experiments and analyses.

Section 5 discusses and compares the effects of different parameters from multiple perspectives. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the overall model and outlines future development directions.

4. Results

This section provides a detailed introduction to the dataset used in the experiment, parameter settings, model comparison results, and visualization analysis. We chose to compare the proposed model with eight cutting-edge models commonly used in the HSIC field to evaluate its effectiveness. All tests used the same hyperparameter settings and experimental conditions as the original study to ensure fairness.

4.1. Data Description

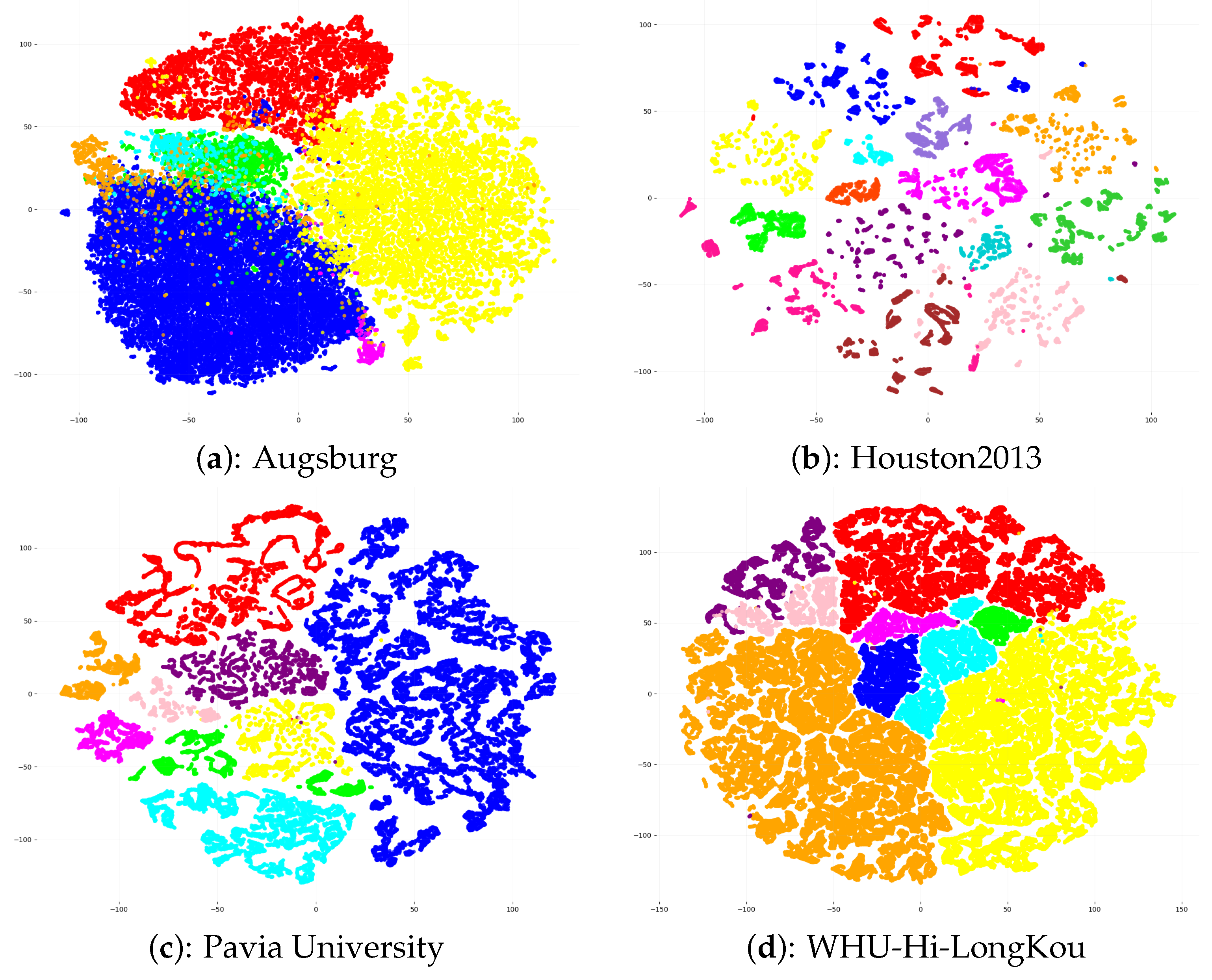

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed model, we conducted comparative experiments using four well-known hyperspectral datasets: the Augsburg dataset (AU), the Houston 2013 dataset (HU2013), the Pavia University dataset (PU), and the WHU-Hi-LongKou dataset (LK). The following subsections will provide detailed information about each dataset.

4.1.1. Augsburg Dataset

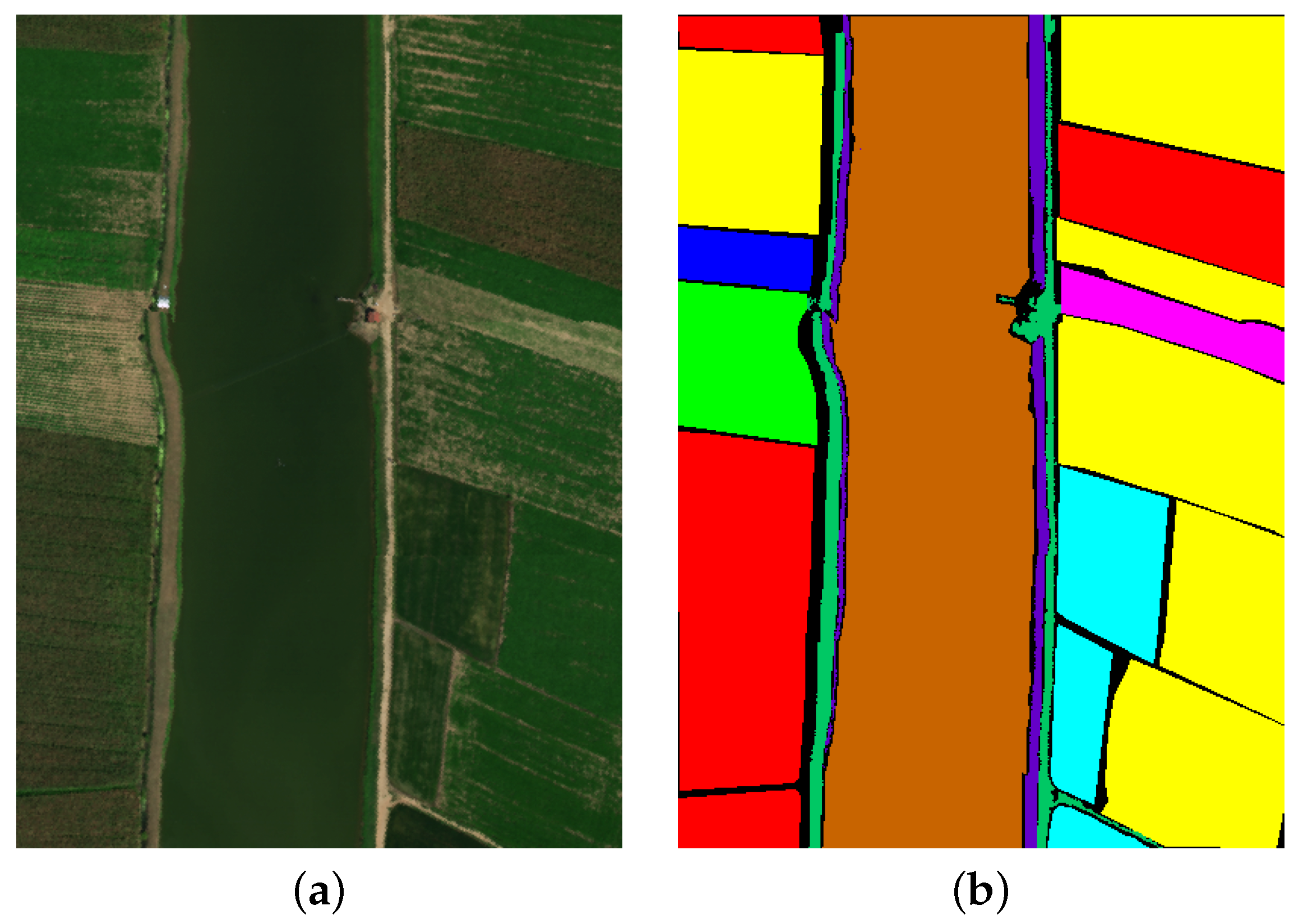

The Augsburg dataset collection utilized three dedicated systems: the HySpex sensor for hyperspectral imaging, the C-band synthetic aperture radar (SAR) sensor installed on the Sentinel-1 satellite, and the DLR-3K system for digital elevation model (DEM) data. The Augsburg dataset is divided into seven categories based on land cover types. The false-color image and the ground truth image of the dataset are shown in

Figure 4.

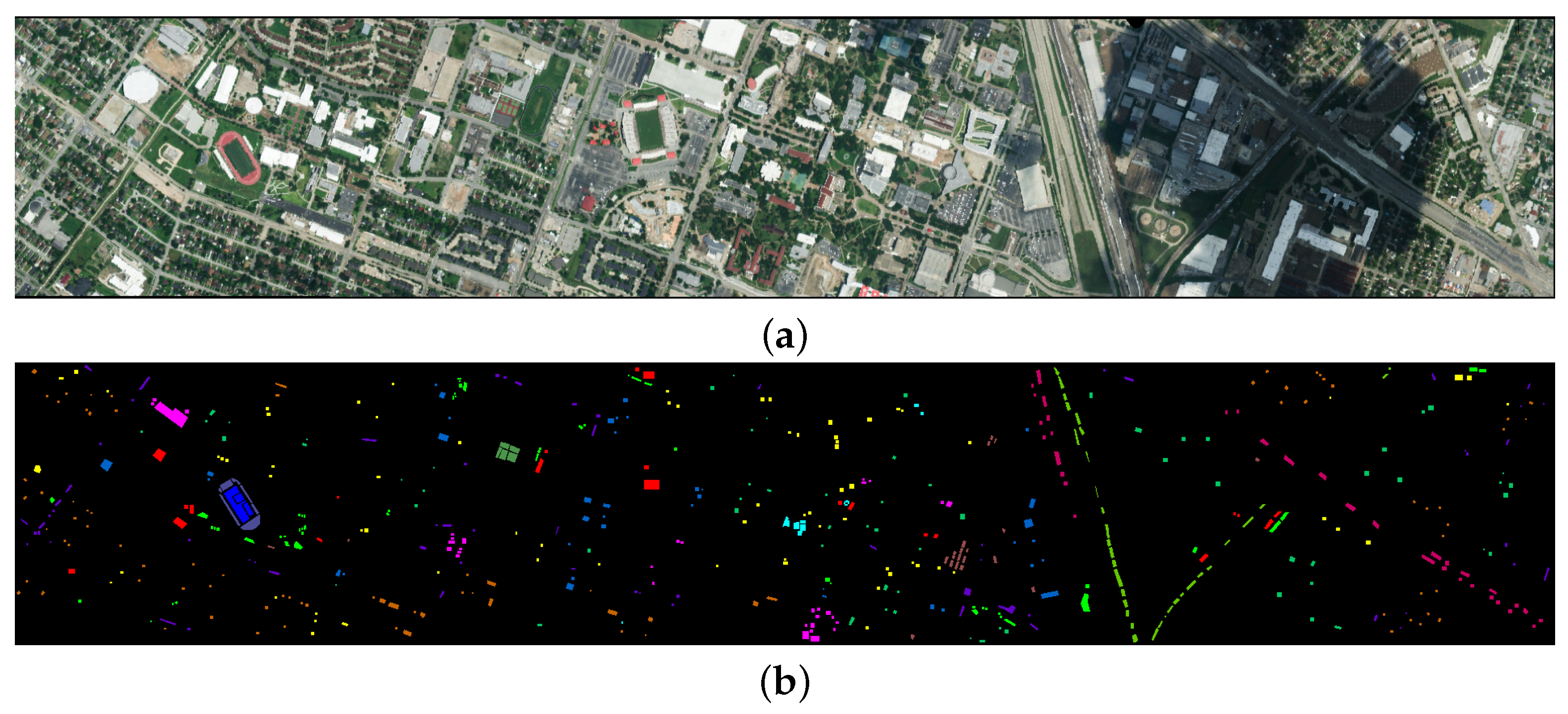

4.1.2. Houston2013 Dataset

The Houston 2013 dataset was acquired by the ROSIS-3 sensor near the University of Houston, Texas, USA, and has a spatial resolution of 2 meters, a spectral range of 430–860 nanometers, 144 bands, and an image size of 349 × 190 pixels, covering 15 land cover types. The false-color image and the ground truth image of the dataset are shown in

Figure 5.

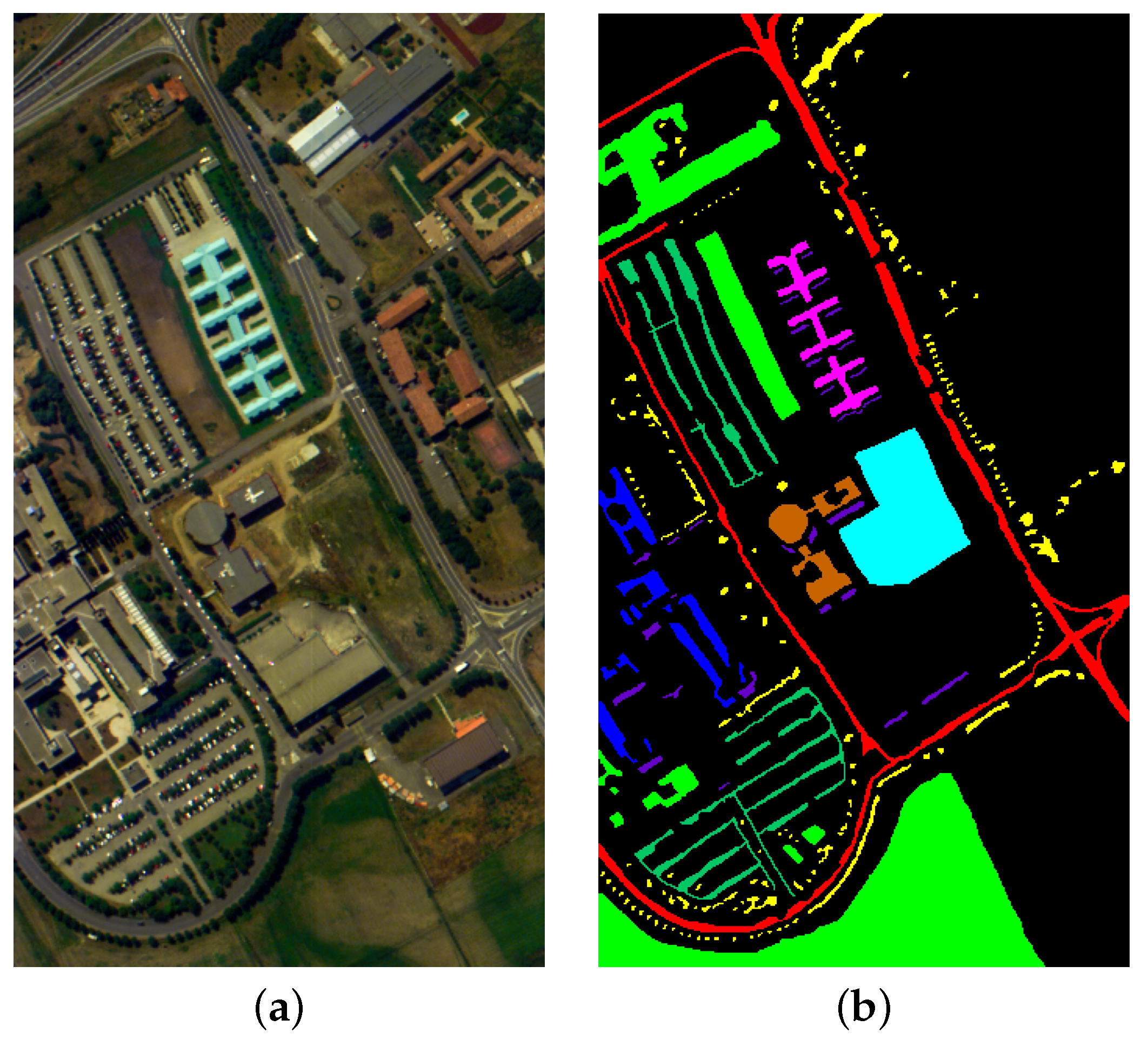

4.1.3. Pavia University Dataset

The Pavia University dataset was acquired using the Reflective Optical System Imaging Spectrometer (ROSIS-3) sensor in Pavia, Italy. It features images with a 610 × 340 pixel resolution across 115 spectral bands. This dataset includes 42,776 annotated samples representing nine land cover categories: asphalt, grassland, gravel, trees, metal debris, bare soil, bricks, and shadows. The false-color image and the ground truth image of the dataset are shown in

Figure 6.

4.1.4. WHU-Hi-LongKou Dataset

The WHU-Hi-Longkou dataset was collected in Wuhan, Hubei Province, using Headwall Nano-Hyperspec imaging sensors. The study area covers a typical agricultural region with nine different land cover types. The dataset contains image files with a 550 × 400 pixels resolution, comprising 270 spectral bands covering a wavelength range of 400 to 1000 nanometers. The false-color image and the ground truth image of the dataset are shown in

Figure 7.

4.2. Experimental Settings

All algorithmic modeling experiments in the article were implemented using Python 3.12.3 and Pytorch 2.5.1, and they were trained on computers equipped with RTX 4060Ti 16 GB GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Intel Core i5-13600KF CPU (Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

The AU, HU 2013, PU, and LK datasets each contain 30 training samples with the remaining samples forming the test set.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 present the distribution of training and test samples for each land cover class within each dataset along with the total number of samples. The hyperparameters are set as follows: the initial learning rate is 0.03, The total number of training epochs for all four datasets is 200, and the learning rate is halved every 50 epochs. To optimize the model, we select the Adam optimizer. Additionally, during the experiments, to eliminate the interference of random factors on the stability of the results, we conduct independent repeated experiments using ten completely randomly generated random seeds to validate the robustness of the model performance fully.

To more thoroughly analyze and compare the classification performance of the proposed model, six commonly used evaluation metrics were selected for the experiment: classification accuracy for each feature category, overall accuracy (OA), average accuracy (AA), Kappa coefficient (Kappa), number of parameters required, and model FLOPS. Additionally, to more intuitively compare the classification performance of each model, visualization charts of the classification results for each comparison model were generated. Finally, all experimental results are based on the average of ten independent runs to achieve more accurate comparisons.

4.3. Experimental Results and Analysis

We selected eight models based on four different categories for comparison. These models include SPRN [

36] and CLOLN [

37] based on CNN, SSFTT [

38] and GSC-VIT [

39] based on Transformer networks, FDGC [

40] and WFCG [

41] based on GCN, and MambaHSI [

42] and IGroupSS-Mamba [

43] based on Mamba networks. Finally, all experiments were conducted under the parameter settings specified in the original paper, using the original hyperparameters to ensure the fairest and most accurate comparison results. The experimental results are the average and variance of ten runs with the specific comparison of experimental results presented in

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8. As shown in the tables, our proposed model achieves the highest OA, AA, and Kappa across all datasets as well as the parameters (K) and FLOPs (M) for each model in the experiments. The results are visualized in

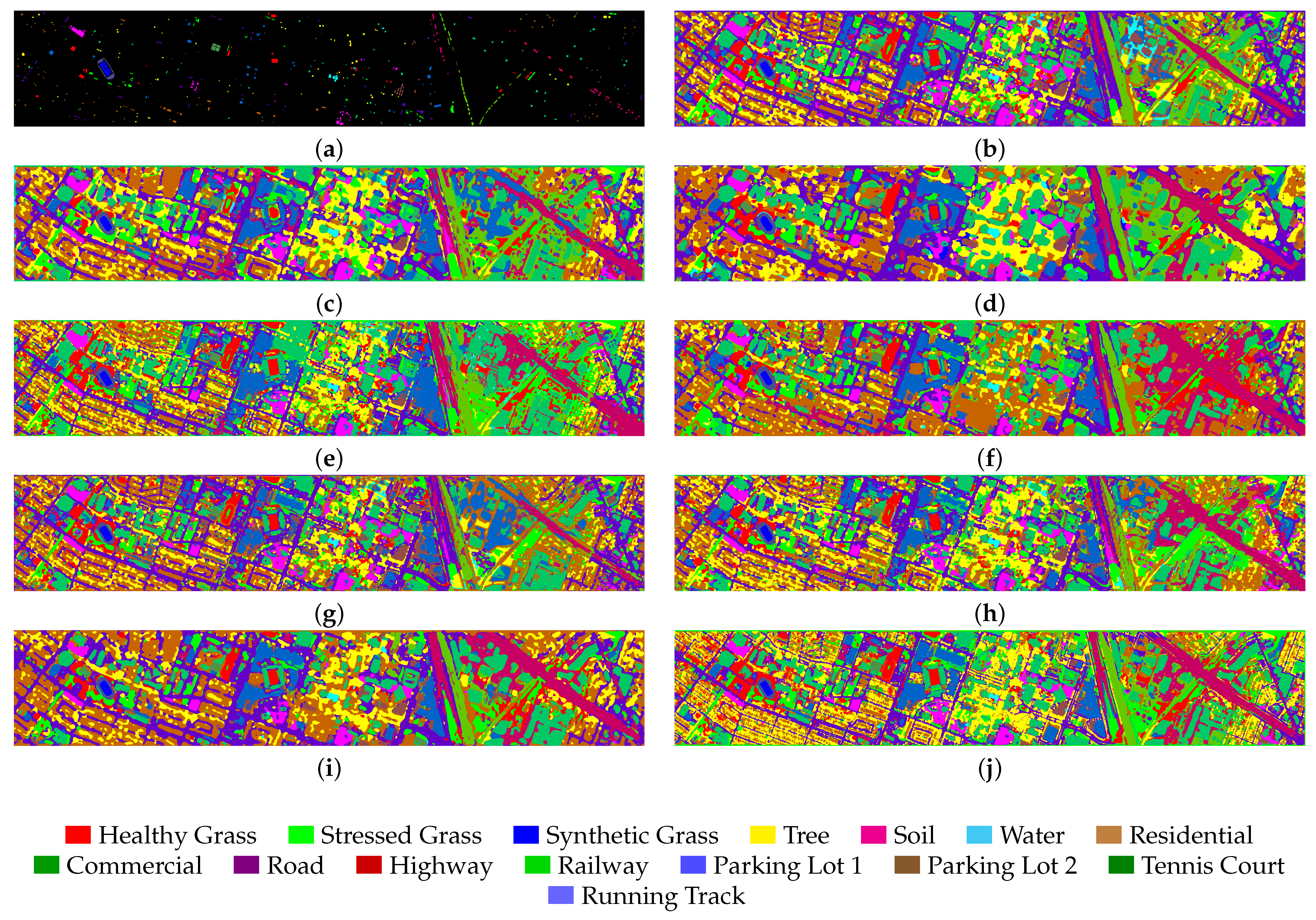

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. In the following subsections, we will analyze the classification performance of different models on the selected datasets.

4.3.1. Results and Analysis on the Augsburg Dataset

As shown in

Table 5, the proposed model achieves the highest performance on OA, AA, and Kappa with respective values of 90.14%, 83.87%, and 86.26%. Compared to the second-best model, IGroupSS-Mamba, our model outperforms it by 2.69% on OA, 1.11% on AA, and 3.53% on Kappa. Meanwhile, we can observe that the GCN-based model FDGC did not achieve good results with an OA of only 77.37%. This may be because GCN relies on iterative learning from neighboring nodes, and when the number of selected samples is small, it is difficult to fully reflect the actual graph structure, which affects feature learning and classification performance. However, the WFCG model achieved better results than the FDGC model. This may be because modifying the traditional GCN to a Graph Attention Network (GAT) enables it to adaptively learn the attention weights between nodes, effectively capturing the complex local dependencies between pixels and thereby improving classification accuracy. Additionally, the SSFTT model based on Transformers, which relies on self-attention mechanisms, can model pixel relationships across the entire domain, outperforming CNN-based models such as SPRN and CLOLN. While the CNN-based model CLOLN does not lead in accuracy, it has the lowest number of parameters and FLOPs, which can be attributed to the CNN’s local perception and weight-sharing design, resulting in significantly fewer parameters and FLOPs compared to fully connected networks. Regarding parameter count and FLOPs, the proposed model also holds a leading position with a classification accuracy superior to that of other models. From

Figure 8, we can see that compared to other comparison models, our proposed model yields smoother classification results and the least noise.

4.3.2. Results and Analysis on the Houston2013 Dataset

As shown in

Table 6, compared to the AU dataset FDGC model, the accuracy has improved on this dataset, which also verifies that the GCN relies on the propagation characteristics of the graph structure, specifically the number of samples. Meanwhile, the Mamba-based model IGroupSS-Mamba still achieved the second-best performance, proving the Mamba module’s effectiveness compared to other models. Meanwhile, we can see that while the WFCG model achieves an intermediate level of classification accuracy, it requires a massive amount of FLOPS, reaching 92,600.4 M, reflecting the significant increase in FLOPS required by GAT as the dataset grows. CLOCN continues to maintain the lowest parameter count and FLOPS. The model we proposed still achieves the highest classification accuracy with the OA reaching 96.63%, the AA reaching 97.11%, and Kappa reaching 96.36%. As shown in

Figure 9, our model still achieves optimal classification performance and remains highly accurate even when dealing with smaller target trees. However, SSFTT exhibits a higher rate of classification errors when dealing with similar targets such as Parking lot 1 and Parking lot 2.

4.3.3. Results and Analysis on the Pavia University Dataset

As shown in

Table 7, the proposed model maintains the best performance in terms of accuracy with OA, AA, and Kappa values all exceeding 98%. At the same time, the parameters and FLPOS of the proposed model are second only to those of the CNN-based model CLOLN, achieving the second-best performance and high accuracy while maintaining low computational complexity. We found that the classification accuracy of IGroupMamba, which has consistently ranked second in the AU and HU2013 datasets, has decreased. This may be because when the dataset contains more complex feature mixtures or increased spatial resolution differences, the difficulty of feature extraction increases, and the interval group space–spectral blocks of IGroupSS-Mamba cannot effectively capture the spatial–spectral context information, leading to a decline in model performance. Additionally, we observed that Mamba-based models outperform those based on the Transformer. This may be because Mamba models, which utilize a selective state space sequence modeling mechanism, can better capture long-range dependencies in long sequences compared to the self-attention mechanism of Transformers, thereby achieving higher accuracy. As shown in

Figure 10, our proposed model exhibits distinct features at object edges, achieving the best classification performance. Meanwhile, as shown in

Table 9, our proposed model achieved a training time of 9.51 s and a testing time of 0.48 s, delivering the second-best performance among all comparison models. This demonstrates that our model attains optimal results within a shorter training cycle, further validating its superiority.

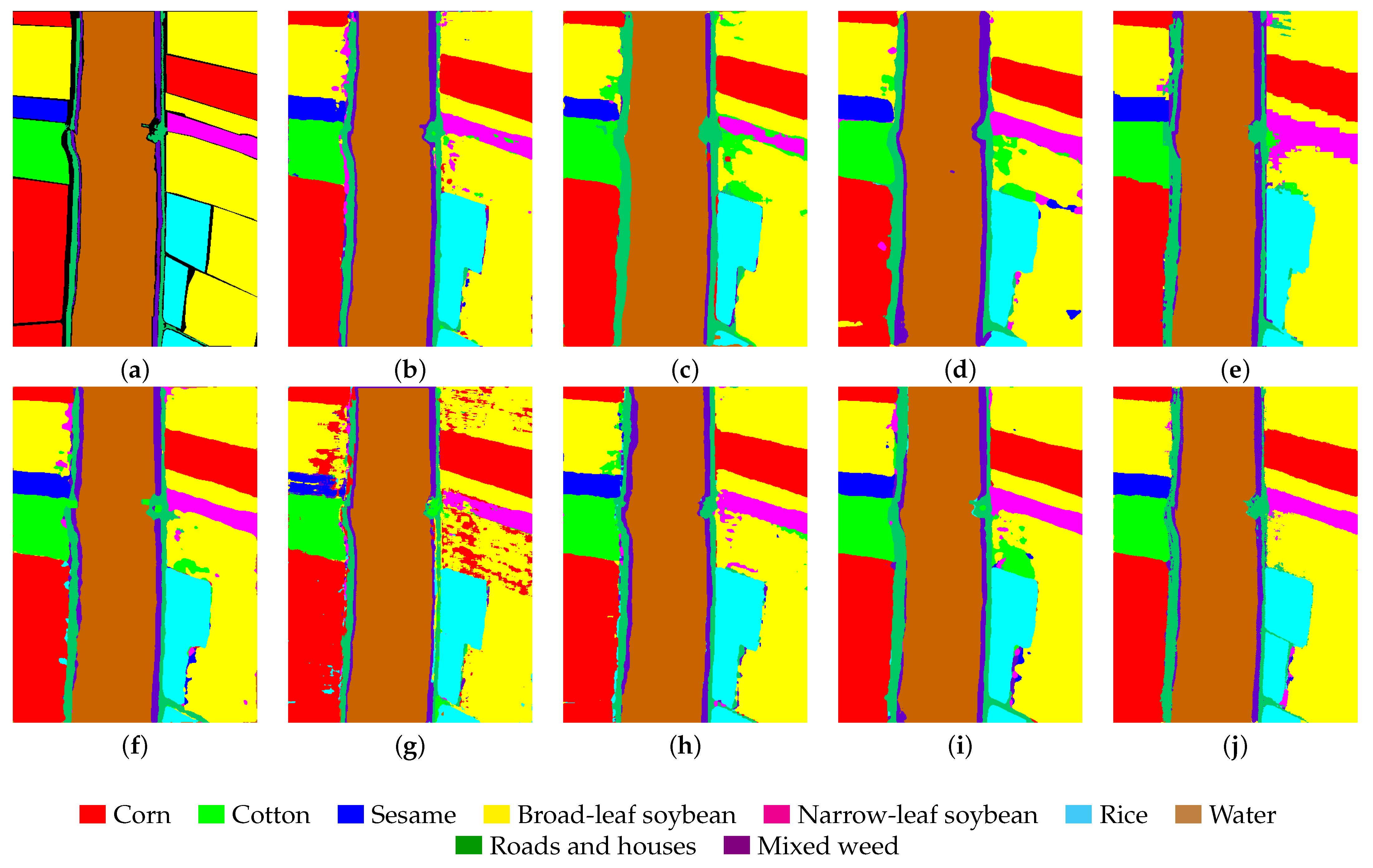

4.3.4. Results and Analysis on the WHU-Hi-LongKou Dataset

As shown in

Table 8, even with the LK dataset, which consists of large images but a small number of training samples, our model outperforms other models. Its OA, AA, and Kappa values are as high as 98.51%, 98.60%, and 98.04%, respectively. Additionally, we can observe that our model achieves the highest classification accuracy across six categories. Furthermore, the OA accuracy of the Mamba-based model exceeds 97%, further validating the advantage of the Mamba model over other models in large-scale classification tasks. Finally, as shown in

Figure 11, the GSC-VIT model exhibits a high error rate in the broadleaf soybean category with significant noise evident in the visualization. Additionally, we can observe that other models exhibit numerous classification errors along the edges in the corn category. In contrast, our proposed model yields the smoothest and most accurate results, further confirming its superiority.