1. Introduction

Being a standard heat- and cold-source device, the chiller unit is a fundamental element of port energy and power systems and is commonly used in emergency situations, including command and control, ship support, and equipment cooling. Optimization of building energy systems has gained more and more research interest in recent years due to the so-called dual-carbon objective and the smart redesigning of energy systems [

1]. It has been statistically demonstrated that the construction of energy system consumes over one-third of the world’s energy and almost 40% of direct and indirect carbon emissions [

2], and heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems consume approximately 40% of total building energy use [

3]. Chiller units are generally subjected to high loads, variable working conditions, and humid marine conditions in naval port stations and therefore are highly susceptible to performance degradation caused by condenser fouling [

4], abnormal water flow, refrigerant leakage and other problems. Although these latent faults might not raise immediate alarm, they slowly diminish performance [

5], and in extreme instances, lead to cooling failures in ship borne systems, hence compromising mission preparedness and supportability.

Different Fault Detection and Diagnosis (FDD) approaches to chiller units have been suggested to enhance equipment reliability and system assurance, typically divided into rule-based [

6], model-based [

7], and data-driven approaches [

8]. The former two are strongly dependent on expert knowledge and system-specific expertise, and hence, their generalization in complex and changing conditions is constrained [

9]. As sensing, artificial intelligence, and big data technologies have advanced, data-driven approaches have become popular in intelligent fault diagnosis [

10]. Specifically, deep learning, due to its powerful feature extracting potential, has demonstrated significant benefits in chiller fault diagnosis [

11]. As an example, Gao [

12] created an SP-CNN model using data augmentation and convolutional neural networks to identify common types of faults with high precision. In the same way, Lu et al. [

13] proposed a better variational autoencoder with a co-training mechanism, which improves the data quality and fault detection performance.

In spite of these developments, the practical use of deep learning in engineering remains a challenge. Deep learning models typically need massive amounts of high-quality labeled data to be trained. In highly reliable industrial applications like the chiller units in the naval port, however, the sensitivity of the operations, the infrequence of fault occurrences, and the complexity of data collection complicate the process of obtaining adequate labelled fault data. This is of particular concern in cross-equipment applications, where labelled samples in the target domain are very few. In addition, the majority of current research is confined to individual devices or homogeneous data sets and lacks the generalization required across devices and operating conditions. The traditional methods tend to fail when transferring a model between a device (source domain) and another (target domain) with different feature dimensions and data distributions (heterogeneity), and where the target domain has only very few, or none, labeled samples [

14]. Therefore, correct diagnosis of chiller faults in cross-equipment and small-sample conditions has become an urgent problem. Transfer learning offers an encouraging solution to the two issues of data scarcity and inter-domain heterogeneity [

15].

Transfer learning seeks to apply knowledge acquired in prior task domains to new tasks [

16]. By integrating labeled data from the source domain with unlabeled data from the target domain, it generates a classifier for the target domain, thereby effectively addressing distributional differences across datasets. Wei et al. [

17] proposed an end-to-end multilayer support vector machine (ML-SVM) architecture that combines transfer learning with an improved oversampling strategy. This approach mitigated data imbalance, reduced noise, and lessened reliance on handcrafted features in multi-class fault diagnosis of mechanical systems. Similarly, Na et al. [

18] introduced a heterogeneous transfer learning method for railway track fault prediction. Their approach reduced the dimensionality of both source- and target-domain features using autoencoders and subsequently constructed a heterogeneous transfer learning network, achieving 99% accuracy on the test dataset.

The literature discussed above suggests that transfer learning has found extensive application in industrial fault diagnosis. But when the fault data of the target equipment are highly sparse or completely unlabeled, source-domain supervision or feature alignment alone cannot be used to achieve high-accuracy diagnosis [

19]. Pseudo-labeling has become an important method of unlabeled transfer learning in recent years. Its fundamental idea is to apply a trained model to the label prediction of samples in the target domain and use high-confidence predictions as pseudo-labels in the training process, which enhances adaptability and generalization to the target domain. Wei et al. [

20] suggested a semi-supervised domain generalization approach that relies on a domain knowledge-directed pseudo-label generation framework, which generated high-quality labels and improved the strength of cross-domain generalization. On the same note, Chen et al. [

21] introduced the Multi-stage Alignment of Multiple Source Subdomains Adaptation (MAMSA) approach that used pseudo-labels generated by the classifier to guide and align it, greatly enhancing diagnostic performance in cross-condition settings. An interpretable domain adaptation transformer has been proposed that leverages the global modeling capabilities of the Transformer architecture and domain adaptation techniques to effectively learn fault features across different operating conditions and machines [

22]. This method provides model interpretability through an ensemble attention weight mechanism and takes raw vibration signals as input, demonstrating its effectiveness in various transfer diagnostic tasks. A deep transfer learning method [

23] has been proposed, which effectively improves the accuracy of cross domain gear fault diagnosis through variational mode decomposition and pre-processing of Gramian angle field, improved residual attention network, and staged transfer training strategy, especially in the case of limited labeled data and significant differences between source and target domains. A transfer learning method [

24] based on improved elastic network was proposed, combined with long short-term memory network (LSTM), to achieve high-precision bearing fault diagnosis under variable load conditions. This method suppresses overfitting and improves training efficiency through elastic networks, requiring only a small amount of target domain data fine-tuning to significantly outperform traditional LSTM, GRU, and Bi LSTM models, demonstrating stronger generalization ability and effectiveness. The articles [

25,

26,

27,

28] reflect two major trends in the field: first, the evolution from models heavily reliant on large amounts of labeled data toward advanced AI models capable of few-shot learning, strong generalization, and privacy preservation (such as domain generalization and federated learning); second, the systematic review and summarization of core tasks in predictive maintenance (e.g., RUL prediction) and key technologies (e.g., health indicators) to further advance the discipline.

Based on these results, this paper concentrates on the chiller unit of a naval port station, where multi-class fault diagnosis scenarios are built and a transfer learning approach is proposed, which combines a domain adversarial training mechanism with a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) and a pseudo-label self-training strategy. The proposed method significantly enhances the cross-equipment diagnostic potential and resilience of chiller units, even under the circumstances of having only a few fault labels in the target domain, by incorporating heterogeneous feature unification at the data level, source-domain model initialization, domain adversarial training, pseudo-label generation, and joint training. This paper presents a novel framework for few-shot cross-equipment diagnosis of military-port chillers by innovatively combining a dual-channel sparse autoencoder with domain adversarial training and pseudo-label learning, which collaboratively boosts generalization via feature alignment and domain adaptation.

3. Dataset Description

In this section, we describe the dataset used to validate the proposed transfer learning method. Experimental studies were conducted on different chiller units under various operating conditions, and both source-domain and target-domain data were collected. The source-domain data were obtained from the ASHRAE-1043 project, while the target-domain data were gathered from a research project on a specific type of screw chiller. The following subsections provide a detailed description of the chiller systems and data collection procedures. In addition, the considered fault types are introduced, and the features employed in this study are summarized.

3.1. Source-Domain Chiller Unit

The source-domain data were obtained from the operational dataset of the chiller unit in the ASHRAE-1043 project. The system consisted of a 316 kW indoor centrifugal chiller using tetrafluoroethane (R-134a) as the refrigerant, designed to investigate six typical chiller faults with varying severity levels (SL). Chiller faults can be primarily categorized into failure-mode faults and degradation-mode faults. Most failure faults can be easily detected with simple albeit sometimes expensive equipment. Degradation faults, on the other hand, generally lead to a loss of performance, but are otherwise not easily detected (since the chiller is often still operational) and cannot normally be detected with a single sensor. Consequently, the degradation faults are shown in

Table 1. Cumulatively, they account for 42% of the service calls. Therefore, these degradation-mode faults were selected as the research focus. Both the evaporator and condenser employed shell-and-tube configurations and were installed as water-cooled flooded-type heat exchangers. To simulate different operating conditions, the original system was modified by adding auxiliary water and steam circuits.

The system was first operated in a fault-free state, after which faults were artificially introduced under laboratory conditions at nearly constant ambient temperatures. The severity of each fault was progressively increased across the test series. A set of predetermined test sequences was defined using the evaporator outlet water temperature, condenser inlet water temperature, and calculated evaporator cooling rate as control variables. Based on these sequences, 27 operating states were established. Each state was continuous, with every fault reaching a steady-state condition before transitioning to the next.

The following is the fault list 1 used in this study as in

Table 1:

3.2. Target-Domain Chiller Unit

For the target-domain dataset, the system consisted of two parts: the experimental test bench and the data acquisition system. The main equipment of the cooling station test bench was a screw chiller unit operating under a return-water temperature control strategy. The chiller unit comprised a compressor, condenser, expansion valve, evaporator, piping accessories, and an electrical control cabinet, all mounted on a common base frame. The data acquisition system was connected to the test bench through sensors such as temperature and pressure transducers. It included both hardware and software components: the hardware comprised data acquisition devices and sensors for temperature, humidity, pressure, flow rate, and electrical parameters, while the software supported data visualization, processing, and storage.

The experimental system and measurement point layout are shown in

Figure 4. As illustrated, the system incorporated not only load control but also fault simulation devices, such as a bypass valve between the compressor suction and discharge pipelines, adjustment valves on the refrigerant circuit, and regulating valves for both cooling and chilled water. Parameter signals from all measurement points were transmitted to the PC host computer via a data acquisition card, enabling continuous sampling, real-time display, and data recording. The performance parameters under rated conditions are shown in

Table 2.

Figure 5 presents a photograph of the actual device. Data collection for the target chiller unit was performed under rated working conditions. The outlet temperature of the chilled water was controlled at 7 °C, while the return temperature of the cooling water was maintained at 20 °C. The compressor capacity was adjusted automatically. After the unit was powered on, the control system executed a self-check, and once no faults were detected, the operating mode was switched to “automatic.” The desired target temperature was then set on the touchscreen, and pressing the automatic start button initiated the reduced-voltage start logic: the compressor contactor engaged, the operation indicator illuminated, and the unit regulated its capacity according to the programmed control logic, using the chilled-water outlet temperature as the reference. The operating status and parameters of the unit could be monitored in real time on the touchscreen.

Reduced condenser water flow rate: On the control screen, the opening of the motorized two-way cooling-water valve (100% indicating fully open) was adjusted. The cooling-water flow rate was monitored and reduced to 90%, 80%, and 70% of the nominal 20 m3/h. After each adjustment, the unit was allowed to stabilize before data variations were observed and recorded.

Reduced evaporator water flow rate: Similarly, the opening of the motorized two-way chilled-water valve (100% indicating fully open) was adjusted. The chilled-water flow rate was monitored and reduced to 90%, 80%, and 70% of the nominal 12 m3/h. After each adjustment, the unit was stabilized before recording data variations.

Excessive refrigerant charge: At the location indicated in

Figure 6, additional R134a refrigerant was charged in increments of 3 kg (10%), 6 kg (20%), and 9 kg (30%). Following each overcharge, the unit was allowed to stabilize, after which data variations were observed and recorded.

Insufficient refrigerant charge: After the unit was fully evacuated, R134a refrigerant was recharged at the location shown in

Figure 6 in increments of 18 kg (60%), 22.5 kg (80%), and 27 kg (90%) of the nominal charge. Following each incremental charge, the unit was allowed to stabilize before data variations were observed and recorded.

Presence of non-condensable gases: At the location indicated in

Figure 4, nitrogen was injected into the system in increments of 3 kg (10% of the refrigerant charge) and 6 kg (20%). After each injection, the unit was allowed to operate until stabilization, after which data variations were observed and recorded.

Table 3 presents the fault simulation table:

The variables collected by the sensors are listed in

Table 4:

3.3. Data Processing

Since chiller unit operation typically involves startup, steady-state, and shutdown stages, the raw data exhibit strong non-stationarity. To improve the stability and robustness of the diagnostic model, a steady-state detector was developed using the Savitzky–Golay (SG) filter in combination with the backward difference (BD) method to identify and extract representative steady-state operating segments.

As a front-end preprocessing module, the SG filter applies local polynomial fitting for signal smoothing. Specifically, a second-order polynomial (polyorder = 2) is fitted within a sliding window of 15 points (equivalent to 1.5 min of data) using the least squares method, and the central point of the window is replaced by the fitted value. The selection of window length and polynomial order balances noise suppression against feature preservation: larger window lengths improve smoothing but risk diminishing abrupt features (e.g., temperature steps induced by faults), whereas low-order polynomials (order 2–3) maintain the overall signal shape while avoiding overfitting.

Compared with traditional moving-average filtering, the SG filter exhibits superior shape-preserving performance. It retains peak and edge characteristics (e.g., early fault fluctuations of ±0.5 °C) and avoids the feature loss caused by excessive smoothing. The results of SG filtering are illustrated in

Figure 7.

BD Method: A geometrically weighted steady-state detection algorithm was employed, with its core principle relying on statistical feature analysis within a sliding window. The window length was set to 180 s (), and the sampling interval was 10 s (). To emphasize recent observations, an exponential decay weight was applied, with the weighting coefficient defined as ).

Within each sliding window, the weighted standard deviations of the evaporator inlet temperature (TEI), evaporator outlet temperature (TEO), and condenser inlet temperature (TCI) were calculated. When the standard deviations of all three parameters simultaneously fell below the threshold of 0.1 °C, the system was considered to have reached a steady-state condition. The extracted steady-state data were subsequently used as inputs for feature learning and classification. The results of BD-based steady-state detection are presented in

Figure 8.

Table 5 presents the processed datasets of the source-domain and target-domain chiller units, where each type of fault data is divided into three categories.

4. Model Training and Detailed Settings

4.1. Training Procedure

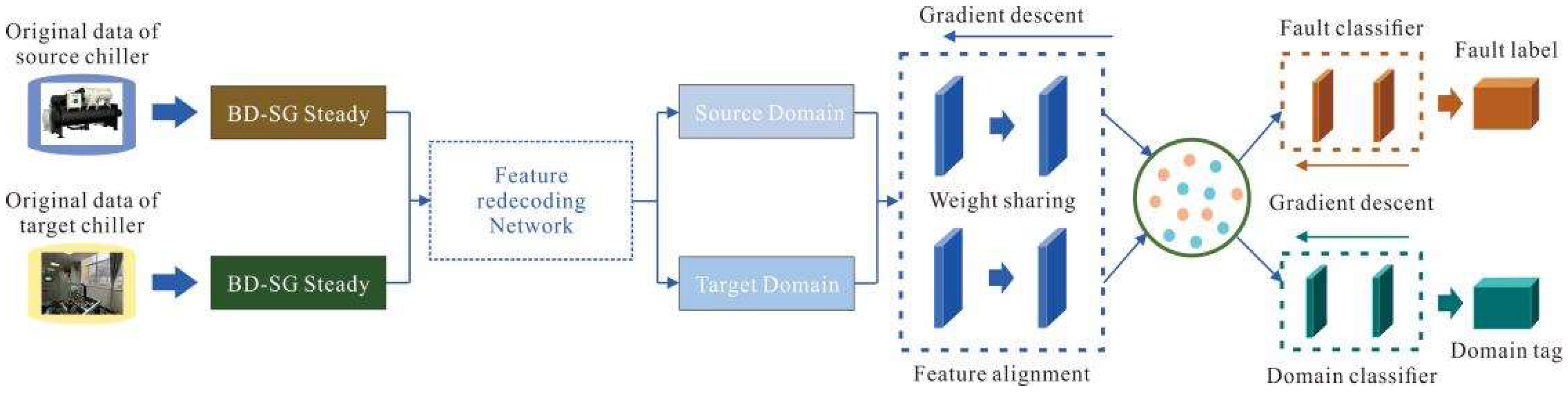

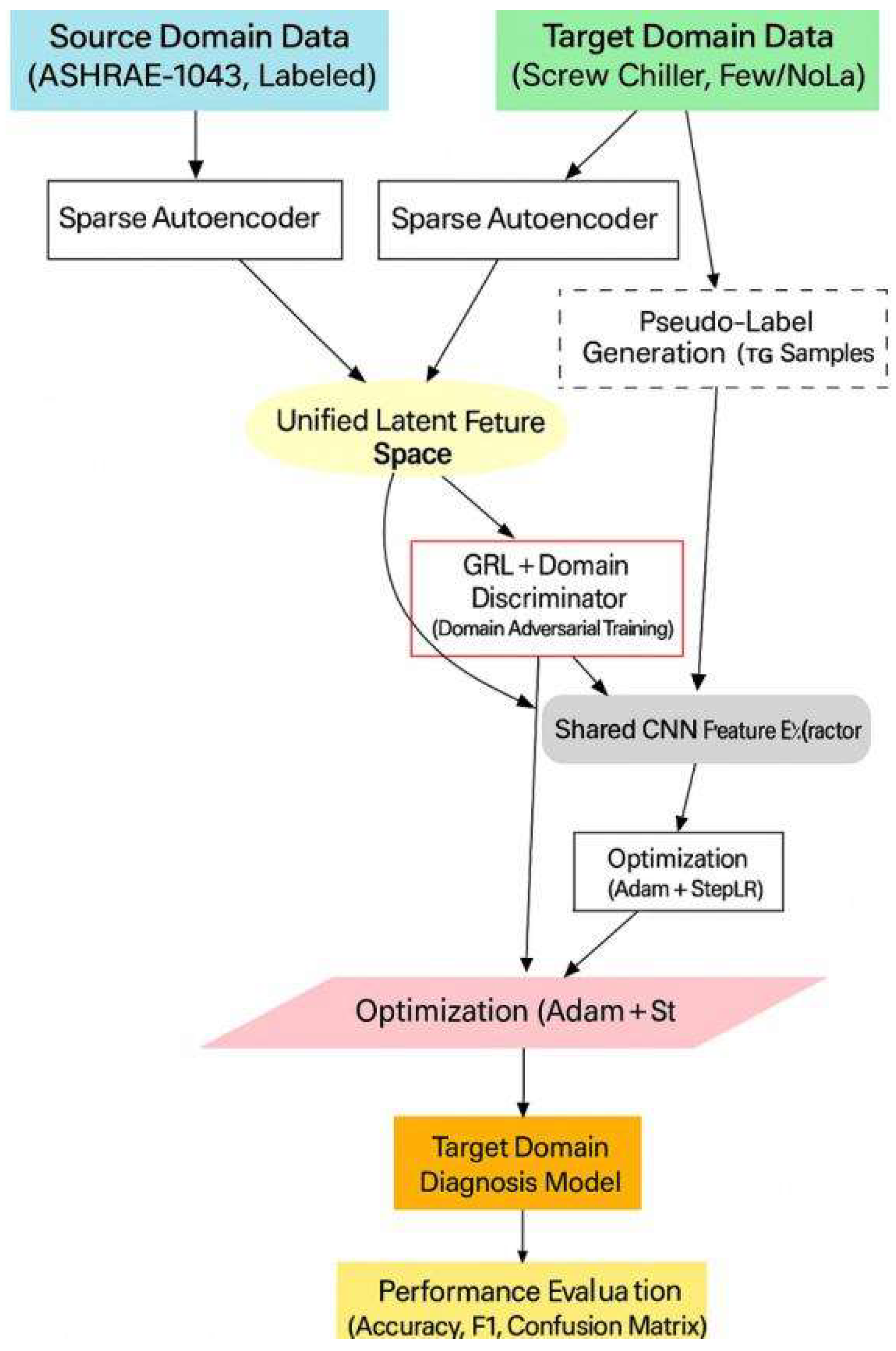

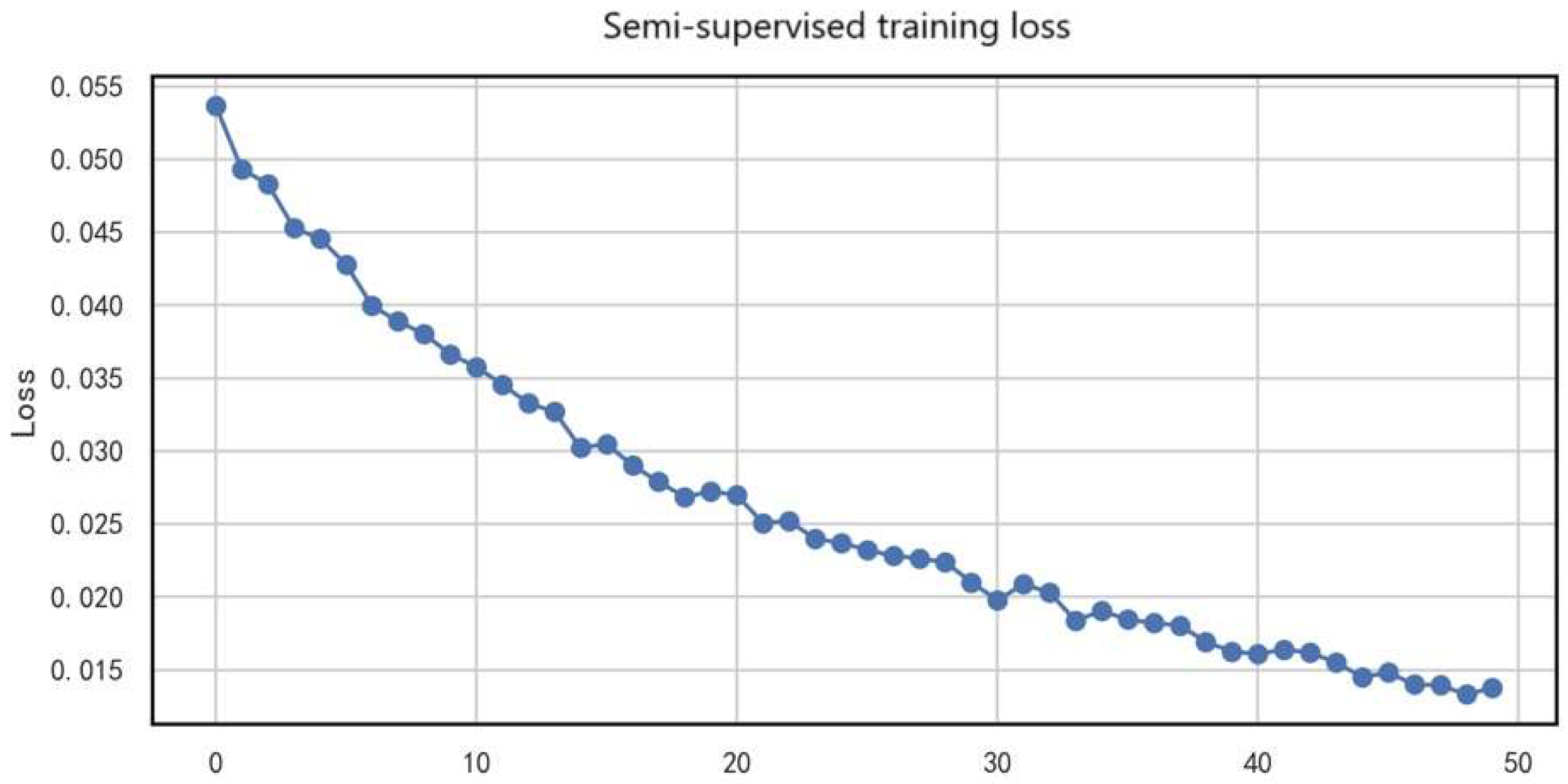

This study proposes a dual-stage joint training framework to address the challenges of scarce labeled data in the target domain (screw chiller units) and cross-domain distribution discrepancies in fault diagnosis for naval vessel chiller systems. The framework combines pseudo-label self-training and domain adversarial training to achieve effective knowledge transfer from the label-rich source domain to the target domain. The overall training process is illustrated in the figure below, which can be understood from three aspects:

Data Input and Feature Mapping

Data Sources: The model simultaneously receives two types of data:

Source Domain Data: From the public ASHRAE-1043 dataset, containing abundant fault samples and corresponding labels.

Target Domain Data: Operational data from the target naval vessel screw chiller units, with only limited or no labels.

Feature Preprocessing and Unification: Source and target domain data are preprocessed separately using sparse autoencoders (SAE_1 and SAE_2). This step aims to learn sparse representations of the data, filter out noise, and project heterogeneous data into a unified latent feature space, laying the foundation for subsequent domain alignment.

Core Mechanism: Dual-Stage Joint Training

The core of the framework lies in the synergistic iteration of pseudo-label generation and domain adversarial training.

Stage 1: Pseudo-Label Self-Training

The model first trains a shared CNN feature extractor and classifier using labeled source domain data to establish preliminary fault diagnosis capability. This model is then applied to the target domain data to generate high-confidence pseudo-labels. These high-quality target domain samples with pseudo-labels are incorporated into the training set to gradually guide the model in adapting to the target domain characteristics.

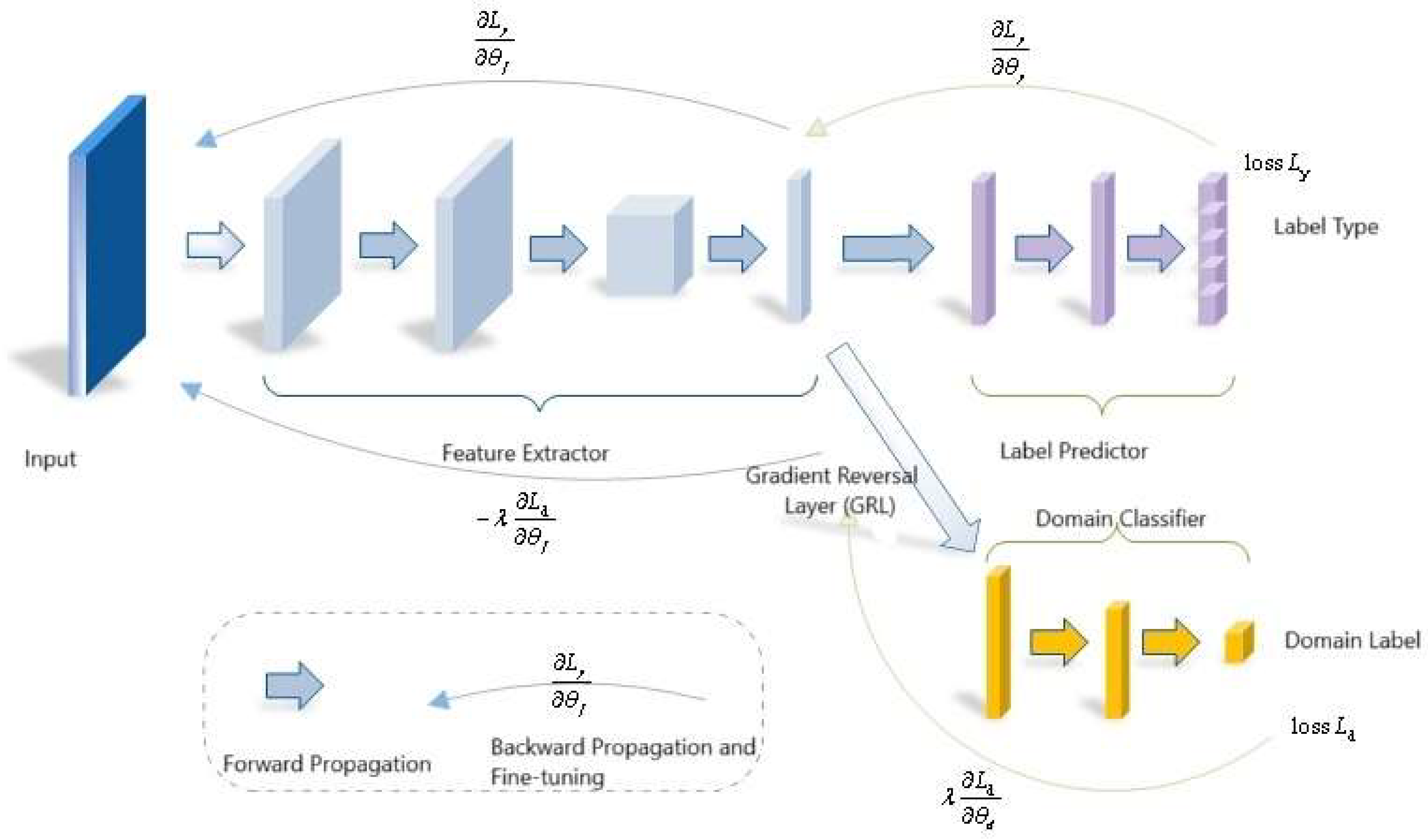

Stage 2: Domain Adversarial Training

To achieve more thorough domain-invariant feature learning, the framework introduces a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL) and a domain discriminator. The shared CNN feature extractor aims to generate features that can deceive the domain discriminator, making it unable to distinguish whether the features originate from the source or target domain. The domain discriminator, in turn, strives to correctly identify the feature sources. Through this adversarial process, the feature extractor is compelled to learn deep features that are domain-agnostic and highly generalizable.

Note: The two stages are not sequential but jointly conducted and mutually reinforcing. The quality of pseudo-labels improves as feature domain invariance enhances, while more accurate target domain pseudo-labels help the domain discriminator better model distributions, further improving domain alignment.

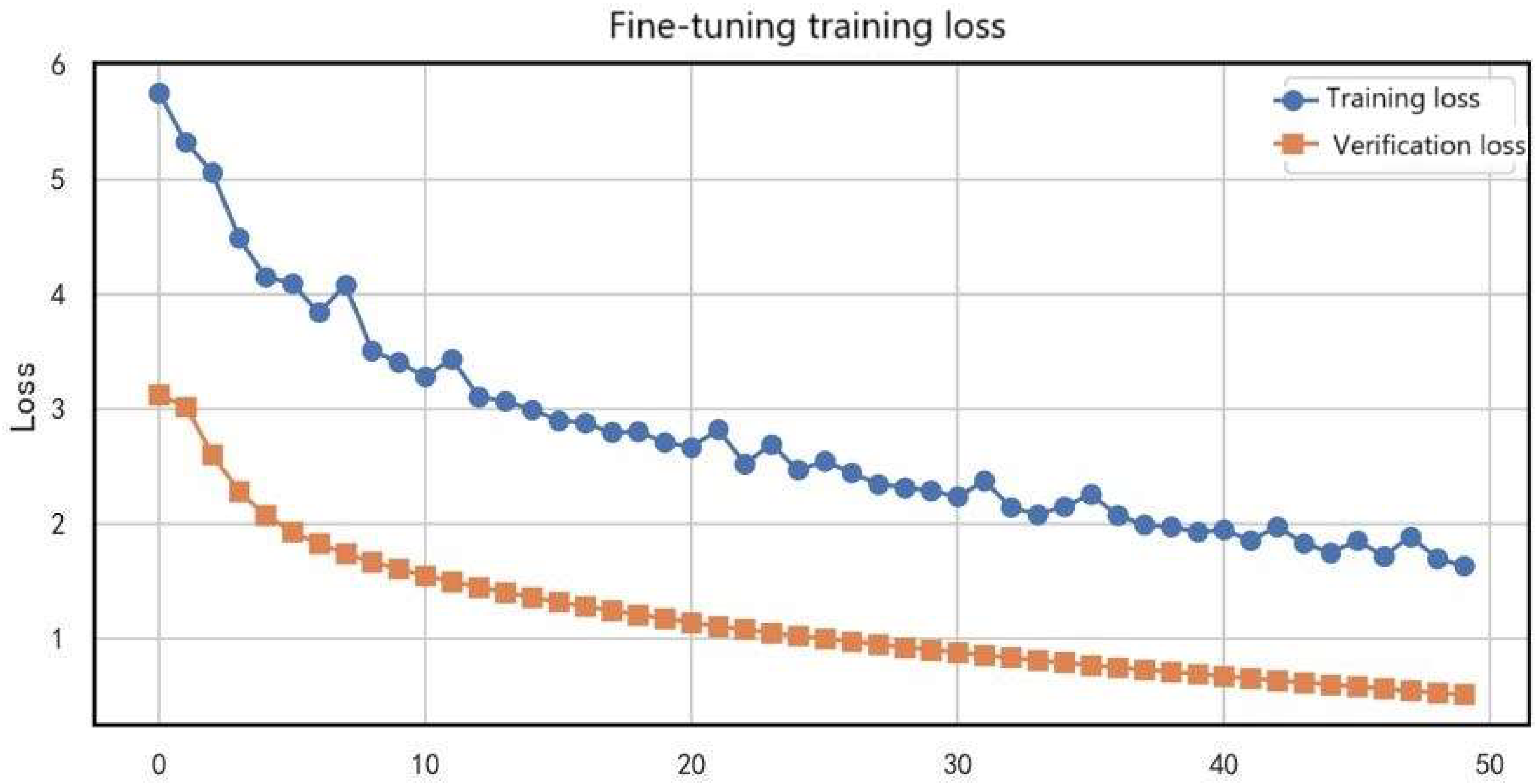

Model Optimization and Output

Optimization Strategy: The Adam optimizer combined with a StepLR learning rate scheduler is used to jointly optimize all model parameters. The optimization objective simultaneously minimizes the classification error (based on source domain true labels and target domain pseudo-labels) and the domain discrimination error.

Model Output: After training, a fault diagnosis model applicable to the target naval vessel screw chiller units is obtained.

Performance Evaluation: The final model is comprehensively evaluated on an independent test set using metrics such as Accuracy, F1-score, and Confusion Matrix.

The training flowchart is as follows in

Figure 9:

4.2. Optimizer and Learning Rate Strategy

Optimizer: Adam, with an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−4, β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999;

Learning rate decay strategy: StepLR, decaying to 0.5 of the original rate every 20 epochs;

Weight decay coefficient: 0.0005;

Batch size: 64.

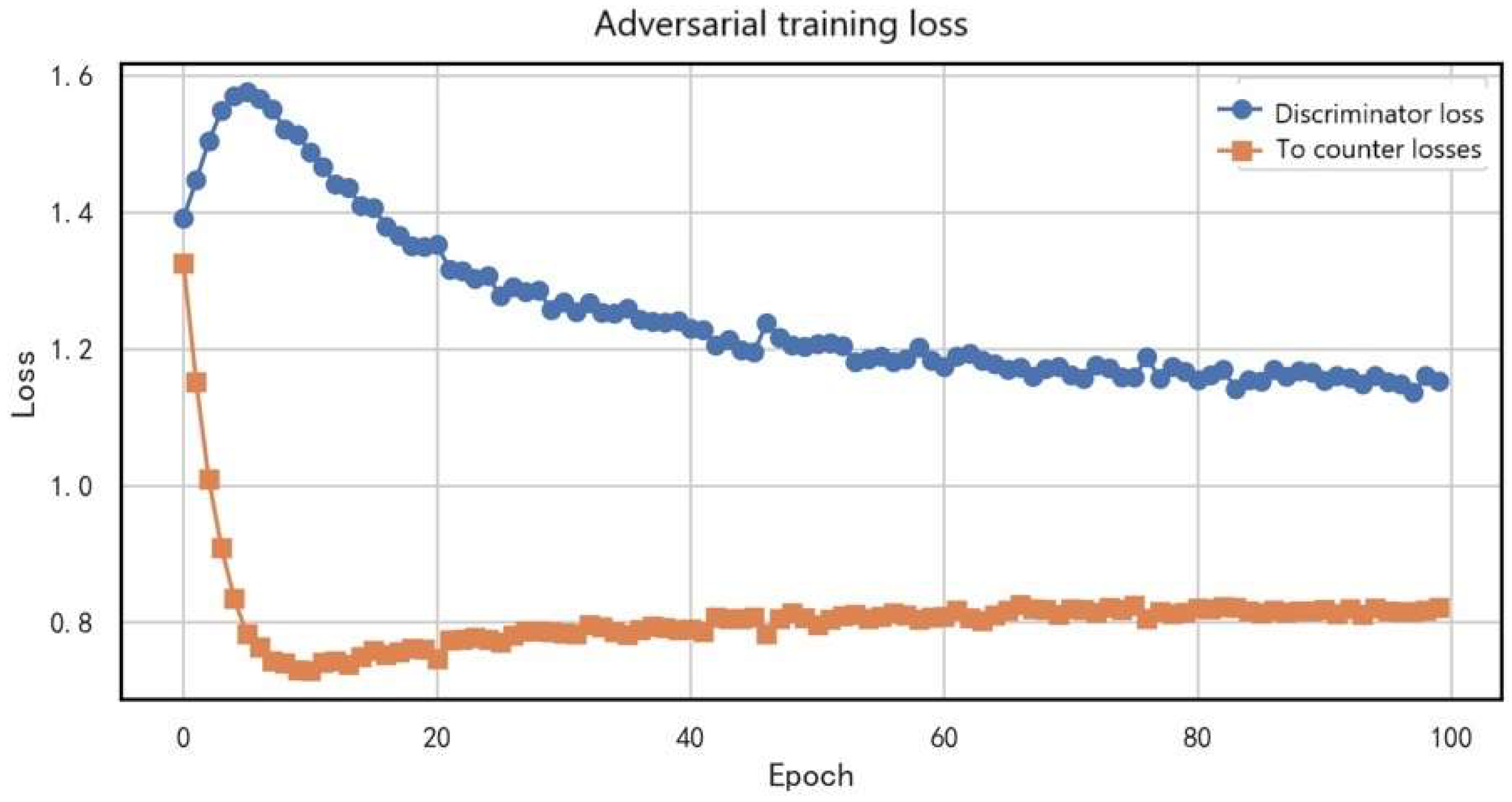

4.3. Parameter Settings

Hyperparameter settings have a significant impact on model performance. Based on preliminary experimental validation and common configurations in the field, the following key hyperparameter values were determined: the latent dimension was set to 64 to balance feature representation capability and computational complexity; the sparsity rate ρ was set to 0.05, and a sparsity penalty coefficient β = 0.1 was introduced to promote the learning of more discriminative sparse feature representations. In the loss function, the classification loss weight λ_cls was set to 1.0 as the primary supervisory signal for task optimization, while the adversarial loss weight λ_adv was set to 0.1 to enhance the model’s generalization ability and robustness. The total number of training epochs was set to 100 to ensure sufficient model convergence while avoiding overfitting. All hyperparameters were initially determined through grid search and cross-validation to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the experimental results.

4.4. Model Implementation Details

During the model implementation process, to ensure experimental consistency and reproducibility, this study meticulously designed the data processing, regularization strategies, and evaluation methods. The specific details are as follows:

All input features were first subjected to normalization preprocessing. The Min-Max scaling method was employed to linearly transform the raw data into the [0, 1] interval, thereby eliminating the impact of feature scale differences on model training stability. After model training was completed, the target domain test set was used for performance evaluation. In addition to classification accuracy, the Macro-average F1-Score was adopted to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance across different categories, which is particularly suitable for scenarios with imbalanced class distributions. Simultaneously, a Confusion Matrix was plotted to visually analyze the types of classification errors, facilitating an in-depth investigation of the model’s recognition capability and the sources of bias in practical scenarios.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a heterogeneous transfer learning method that integrates a dual-channel autoencoder, domain adversarial training, and a pseudo-label self-training mechanism. By combining attention mechanisms, adversarial training, semi-supervised learning, and multi-granularity classifiers, the method achieves effective cross-domain knowledge transfer and enhances fault diagnosis performance, enabling accurate few-shot transfer of source domain knowledge to the target domain. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed DDPN model exhibits high fault diagnosis accuracy in the target domain, effectively identifying common faults in various types of chiller units under conventional operating conditions. In multi-class fault diagnosis tasks, the model achieves higher accuracy and F1-scores compared to traditional methods and existing transfer learning approaches.

Despite these promising results, several directions merit further investigation. First, further exploration of the model’s internal mechanisms is needed to enhance interpretability, enabling engineers to better understand the diagnostic basis. Second, optimizing the architecture and inference speed would facilitate deployment in real-time online fault diagnosis systems. Third, incorporating additional sensor modalities, such as vibration and acoustic signals, could yield a more comprehensive diagnostic framework.

The framework proposed in this study demonstrates commendable performance in addressing heterogeneity among chiller units; however, it is essential to objectively acknowledge its inherent limitations. The method achieves high fault diagnosis accuracy in typical industrial application scenarios, enabling effective identification of common faults in various types of chiller units under conventional operating conditions. It should be noted that performance degradation may occur when the method is applied to units with significant structural disparities compared to the training samples, operating conditions far beyond the training scope, or entirely novel fault patterns not present in the source domain. This limitation primarily stems from two factors: (1) the shared feature space learned through the dual-channel autoencoder and adversarial training may struggle to effectively capture fault features with fundamentally different physical mechanisms; (2) the pseudo-label generation mechanism relies on high-confidence predictions, whose reliability significantly decreases when confronted with previously uncharacterized fault manifestations. Consequently, the effectiveness of this method is contingent upon an important premise: the physical principles underlying faults across different units must possess a certain degree of inherent similarity, even though their surface-level data distributions may exhibit substantial differences. To address this limitation, future research will focus on enhancing the model’s generalization capability under extreme operating conditions, potentially through the incorporation of physics-informed embedding models or few-shot learning techniques, thereby improving its ability to handle edge cases.

We fully acknowledge that the proposed method incurs relatively high computational costs, primarily due to the high computational complexity of the neural network training process. However, it should be noted that the computational demands during the model inference phase are relatively modest. The current research has been conducted primarily on laboratory servers, focusing on principle validation and methodological feasibility demonstration. For subsequent practical shipboard deployment, we suggest optimizing and improving the system through the following two aspects to significantly reduce computational load: adoption of an offline training-online deployment paradigm: the training process will be completed on high-performance servers before deploying the optimized models to practical edge computing platforms; advancement of model lightweighting research: implementation of advanced techniques such as neural network pruning and quantization compression to further enhance operational efficiency.