Statistical Mechanics of Directed Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. General Formalism

2.1. Fermionic Approach to Directed Networks

- the number of fermions (links) is fixed on average;

- The average energy is fixed as well.

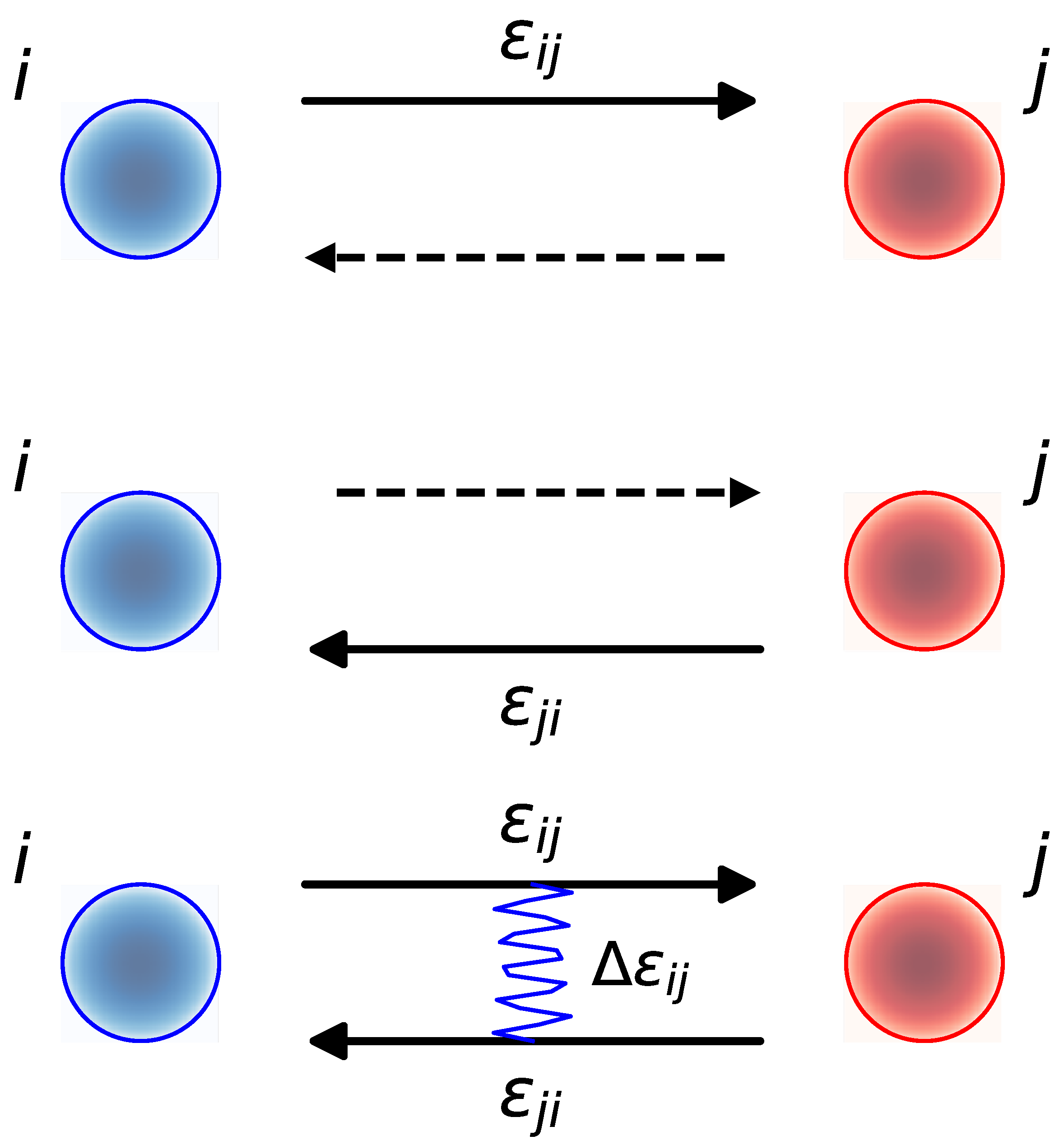

2.2. Non-Interacting Fermions

2.3. Interacting Fermions

3. Specific Random Network Models

3.1. Directed Configuration Model

3.1.1. Non-Interacting Directed Configuration Model (NI-DCM)

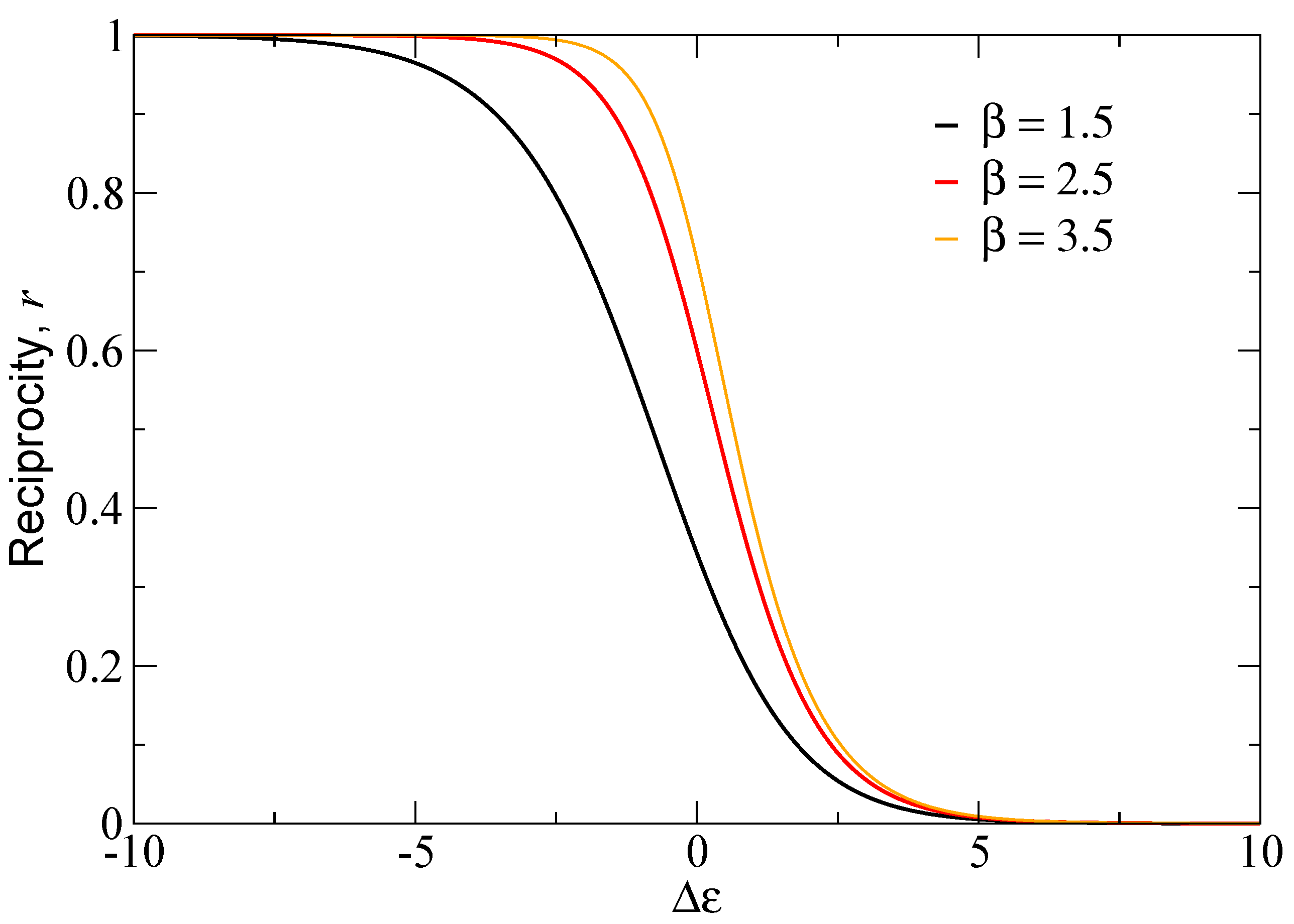

3.1.2. Interacting Directed Configuration Model (I-DCM)

3.2. Directed Model

3.2.1. Non-Interacting Directed Model (NI-DSM)

3.2.2. Interacting Directed Model (I-DSM)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newman, M.E.J. Networks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bianconi, G.; Gulbahce, N.; Motter, A.E. Local Structure of Directed Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 118701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asllani, M.; Lambiotte, R.; Carletti, T. Structure and dynamical behavior of non-normal networks. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaau9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguñá, M.; Serrano, M.Á. Generalized percolation in random directed networks. Phys. Rev. E 2005, 72, 016106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, M.Á.; De Los Rios, P. Interfaces and the edge percolation map of random directed networks. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 76, 056121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serrano, M.Á.; Boguñá, M.; Vespignani, A. Patterns of Dominant Flows in the World Trade Web. J. Econ. Interact. Coord. 2007, 2, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.Á.; Klemm, K.; Vazquez, F.; Eguíluz, V.M.; San Miguel, M. Conservation laws for voter-like models on random directed networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2009, 2009, P10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asllani, M.; Challenger, J.D.; Pavone, F.S.; Sacconi, L.; Fanelli, D. The theory of pattern formation on directed networks. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muolo, R.; Carletti, T.; Gleeson, J.P.; Asllani, M. Synchronization dynamics in non-normal networks: The trade-off for optimality. Entropy 2020, 23, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nartallo-Kaluarachchi, R.; Asllani, M.; Deco, G.; Kringelbach, M.L.; Goriely, A.; Lambiotte, R. Broken detailed balance and entropy production in directed networks. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 110, 034313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Newman, M.E.J. Statistical mechanics of networks. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 70, 066117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianconi, G. Entropy of network ensembles. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 79, 036114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garlaschelli, D.; Loffredo, M.I. Patterns of link reciprocity in directed networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93, 268701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagiolo, G. Clustering in complex directed networks. Phys. Rev. E—Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2007, 76, 026107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahnert, S.E.; Fink, T.M.A. Clustering signatures classify directed networks. Phys. Rev. E 2008, 78, 036112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, A.; Serrano, M.Á.; Boguñá, M. Geometric description of clustering in directed networks. Nat. Phys. 2024, 20, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Newman, M.E.J. Origin of degree correlations in the Internet and other networks. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 68, 026112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Kolk, J.; Serrano, M.Á.; Boguñá, M. An anomalous topological phase transition in spatial random graphs. Commun. Phys. 2022, 5, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Del Genio, C.I.; Bassler, K.E.; Toroczkai, Z. Constructing and sampling directed graphs with given degree sequences. New J. Phys. 2012, 14, 023012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdös, P.; Rényi, A. On random graphs I. Publ. Math. 1959, 6, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, G.; Barabási, A.L. Bose-Einstein Condensation in Complex Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001, 86, 5632–5635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushbrooke, G. On the statistical mechanics of assemblies whose energy-levels depend on the temperature. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1940, 36, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsberg, P. Statitical Mechanics of Teperature-Dependent Energy Levels. Phys. Rev. 1954, 95, 643. [Google Scholar]

- Elcock, E.; Landsberg, P. Temperature dependent energy levels in statistical mechanics. Proc. Phys. Soc. Sect. B 1957, 70, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Miguel, R.; Rubí, J.M. Statistical mechanics at strong coupling: A bridge between Landsberg’s energy levels and Hill’s nanothermodynamics. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguñá, M.; Bonamassa, I.; De Domenico, M.; Havlin, S.; Krioukov, D.; Serrano, M.Á. Network geometry. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.Á.; Boguñá, M. The Shortest Path to Network Geometry: A Practical Guide to Basic Models and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, X.; Krioukov, D.; Fomenkov, M.; Huffaker, B.; Hyun, Y.; Claffy, K.; Riley, G. AS relationships: Inference and validation. ACM SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2007, 37, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, A.; Serrano, M.Á. Navigable maps of structural brain networks across species. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Yang, R.; Dorkenwald, S.; Matsliah, A.; Sterling, A.R.; Schlegel, P.; Yu, S.c.; McKellar, C.E.; Costa, M.; Eichler, K.; et al. Network statistics of the whole-brain connectome of Drosophila. Nature 2024, 634, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.Á.; Krioukov, D.; Boguñá, M. Self-Similarity of Complex Networks and Hidden Metric Spaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 078701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krioukov, D.; Papadopoulos, F.; Kitsak, M.; Vahdat, A.; Boguñá, M. Hyperbolic geometry of complex networks. Phys. Rev. E 2010, 82, 036106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gugelmann, L.; Panagiotou, K.; Peter, U. Random Hyperbolic Graphs: Degree Sequence and Clustering. In Automata, Languages, and Programming; Czumaj, A., Mehlhorn, K., Pitts, A., Wattenhofer, R., Eds.; ICALP 2012, Part II, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7392, pp. 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candellero, E.; Fountoulakis, N. Clustering and the Hyperbolic Geometry of Complex Networks. Internet Math. 2016, 12, 2–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, N.; van der Hoorn, P.; Müller, T.; Schepers, M. Clustering in a hyperbolic model of complex networks. Electron. J. Probab. 2021, 26, 1–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.; Fountoulakis, N.; Bode, M. Typical distances in a geometric model for complex networks. Internet Math. 2017, 1, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, T.; Krohmer, A. On the Diameter of Hyperbolic Random Graphs. SIAM J. Discret. Math. 2018, 32, 1314–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.; Staps, M. The diameter of KPKVB random graphs. Adv. Appl. Probab. 2019, 51, 358–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.Á.; Krioukov, D.; Boguñá, M. Percolation in Self-Similar Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 048701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoulakis, N.; Müller, T. Law of large numbers for the largest component in a hyperbolic model of complex networks. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2018, 28, 607–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiwi, M.; Mitsche, D. Spectral gap of random hyperbolic graphs and related parameters. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2018, 28, 941–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boguñá, M.; Serrano, M.Á. Statistical Mechanics of Directed Networks. Entropy 2025, 27, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27010086

Boguñá M, Serrano MÁ. Statistical Mechanics of Directed Networks. Entropy. 2025; 27(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoguñá, Marián, and M. Ángeles Serrano. 2025. "Statistical Mechanics of Directed Networks" Entropy 27, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27010086

APA StyleBoguñá, M., & Serrano, M. Á. (2025). Statistical Mechanics of Directed Networks. Entropy, 27(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/e27010086