Pentapartite Entanglement Measures of GHZ and W-Class State in the Noninertial Frame

Abstract

1. Introduction

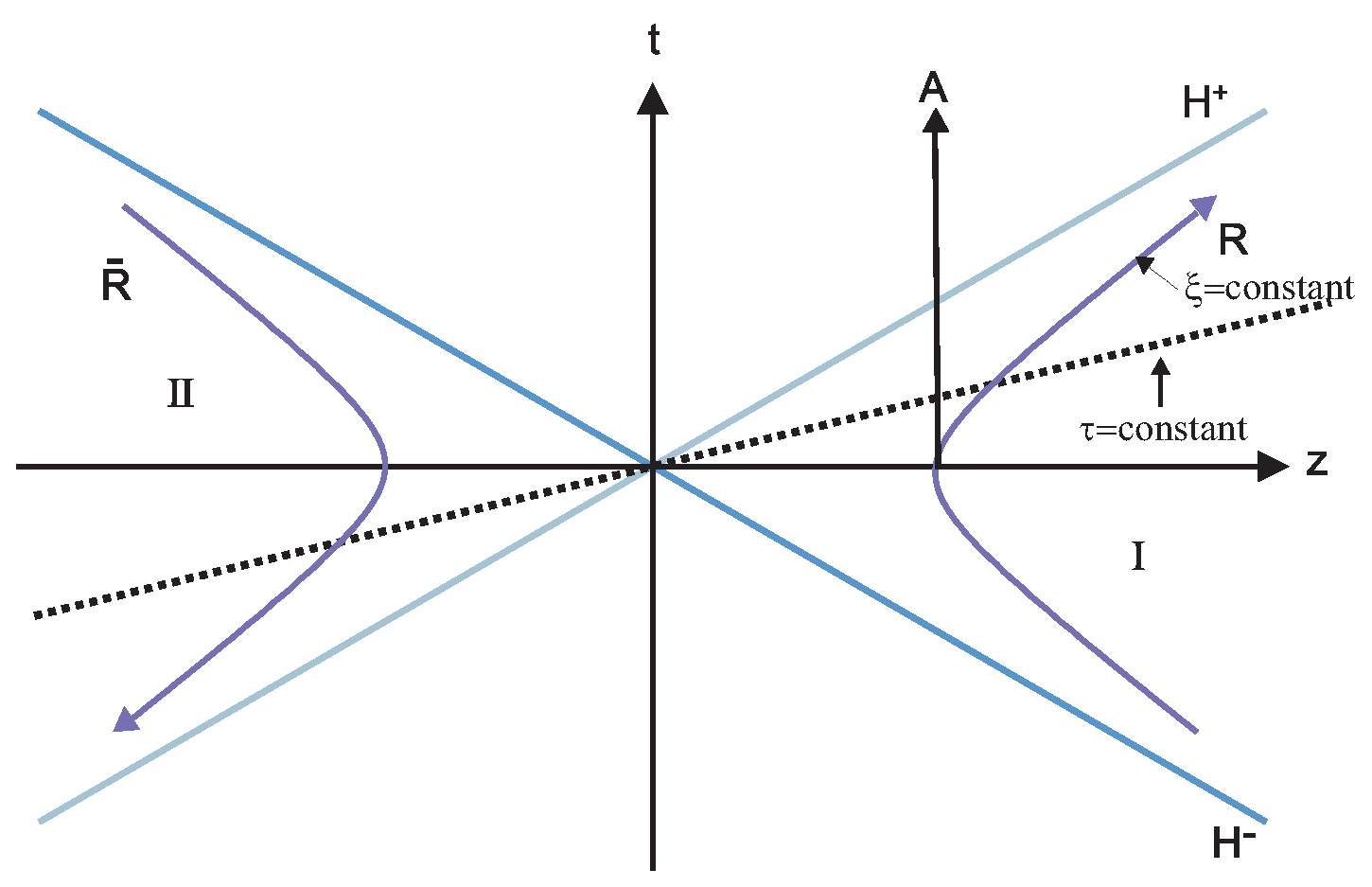

2. Pentapartite Entanglement from One to Five Accelerated Observers

3. Entanglement Measures: Negativity and von Neumann Entropy

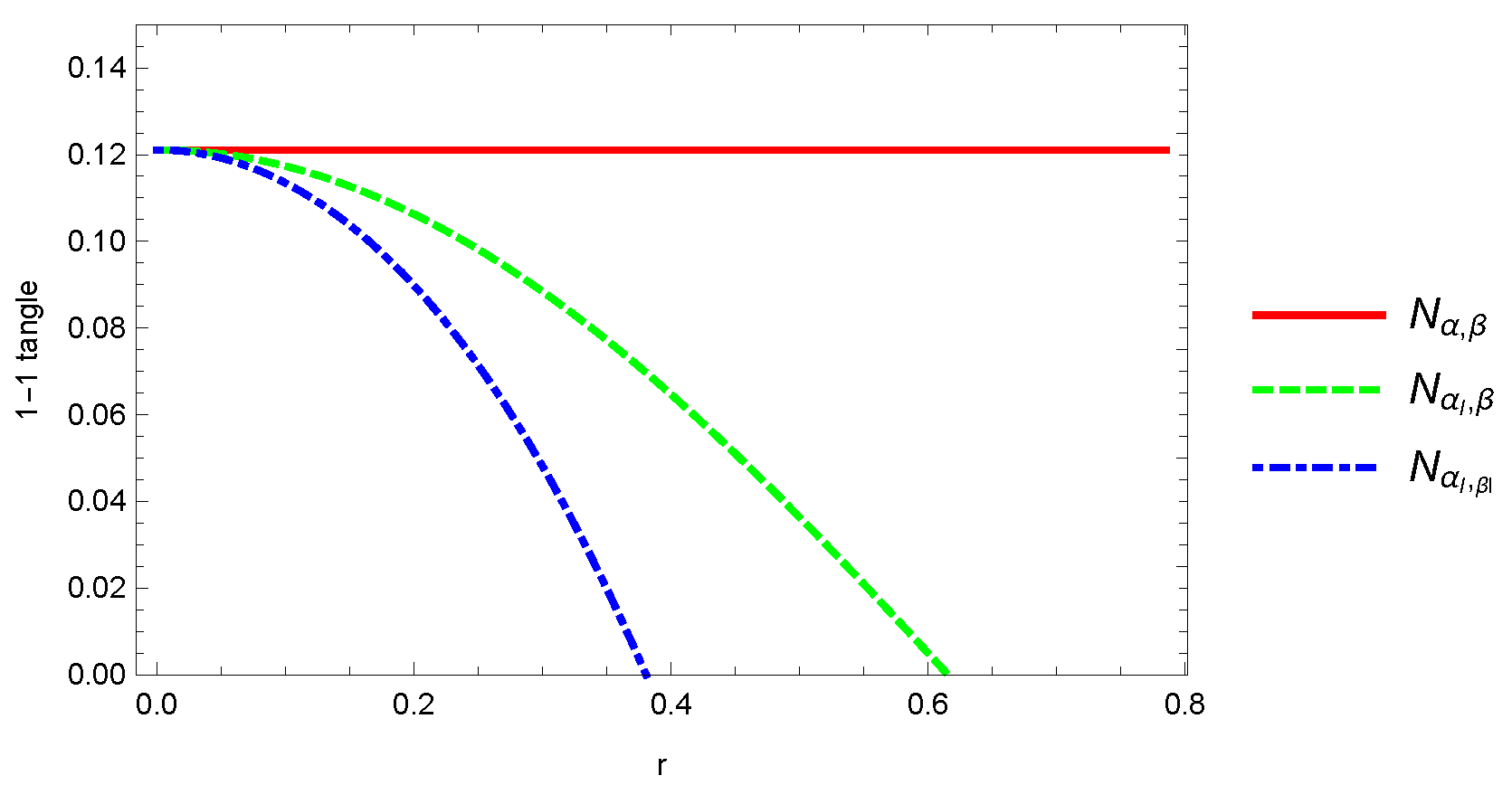

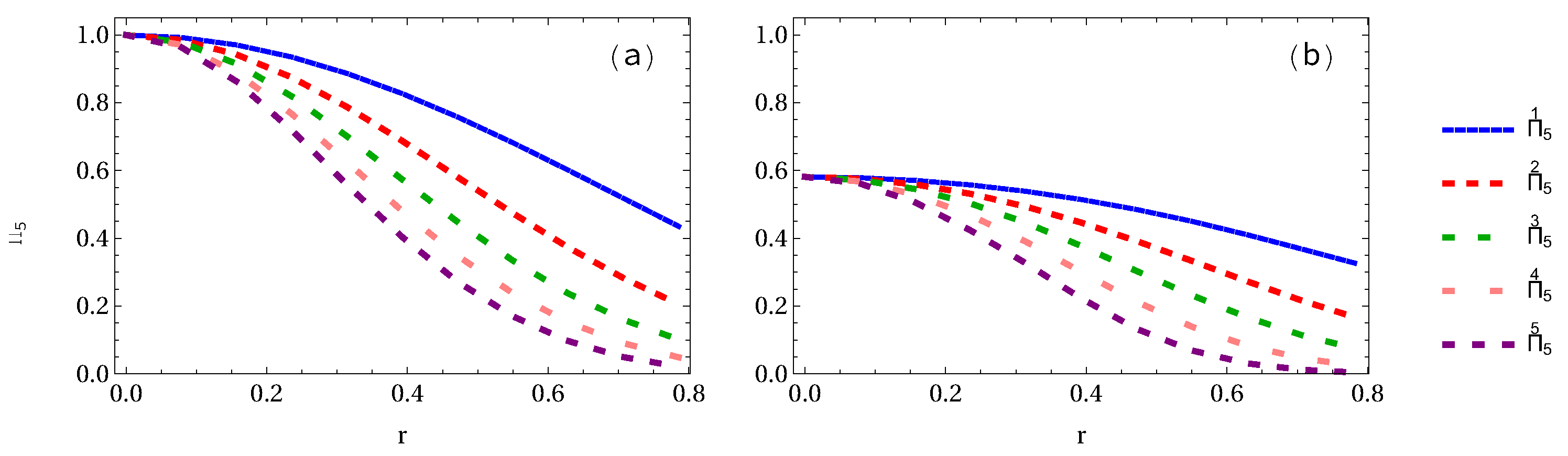

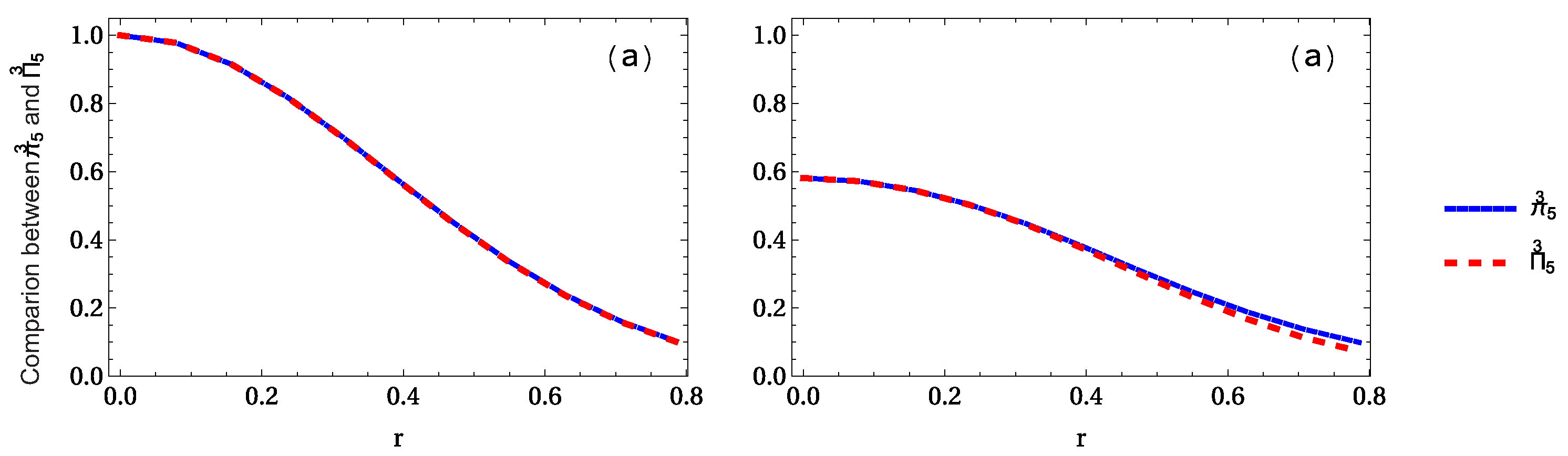

3.1. Negativity

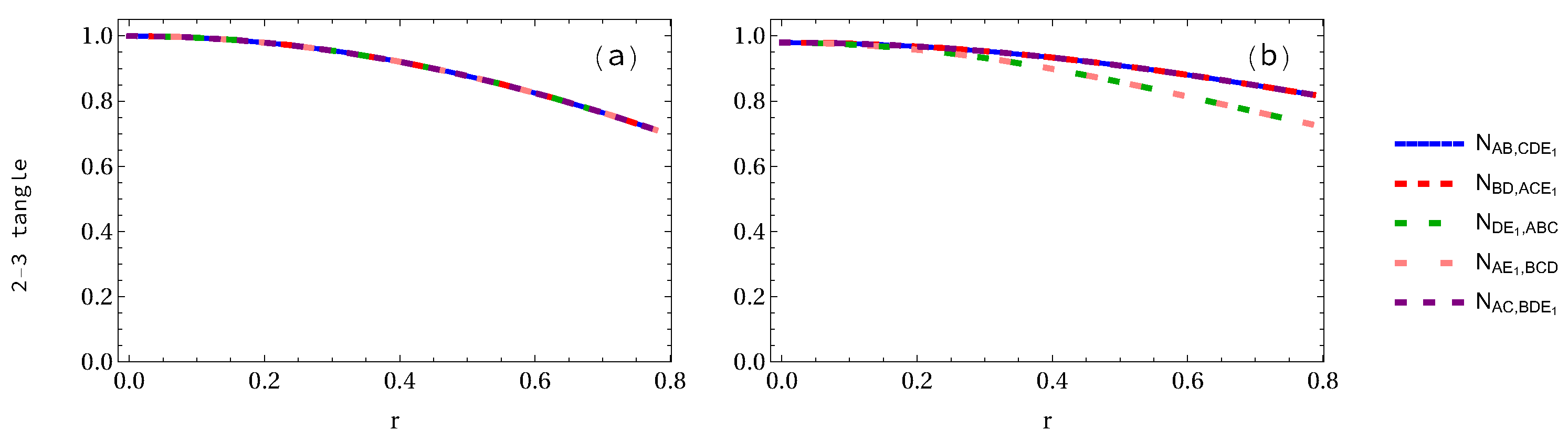

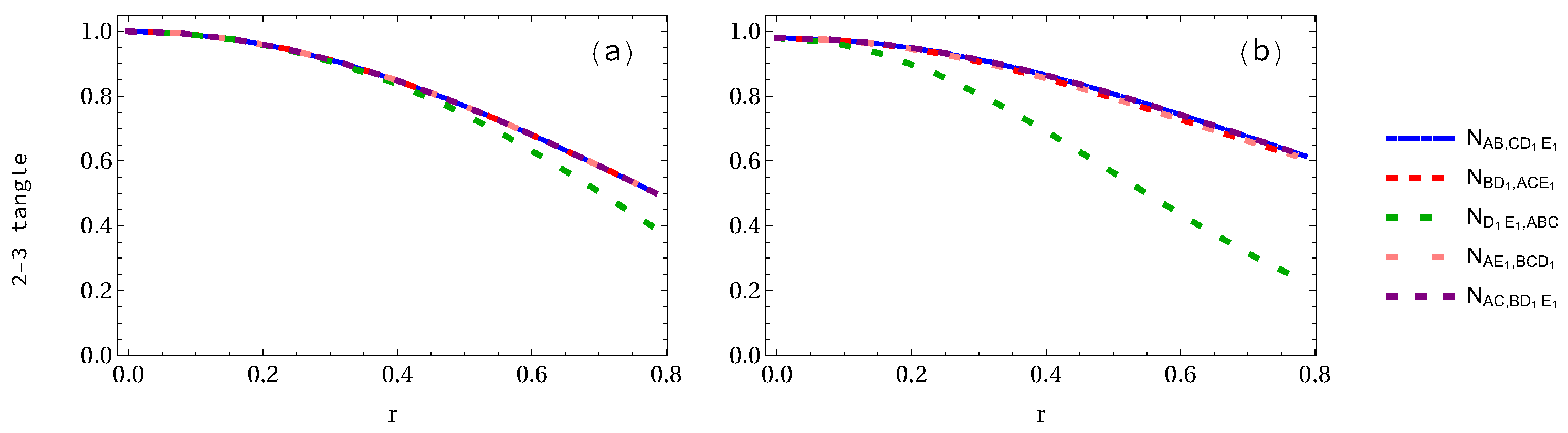

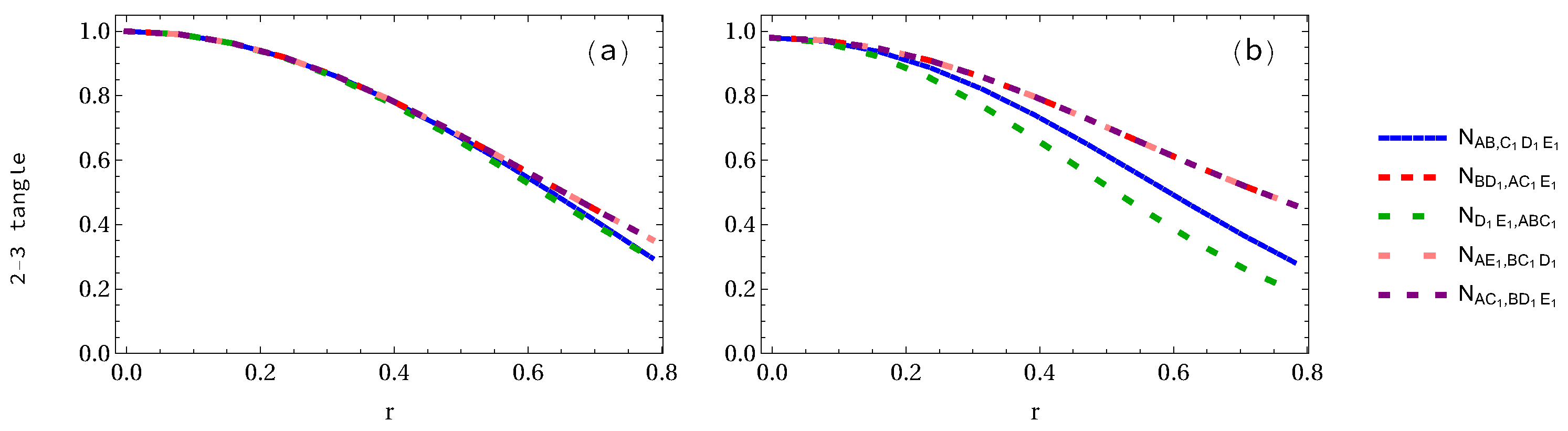

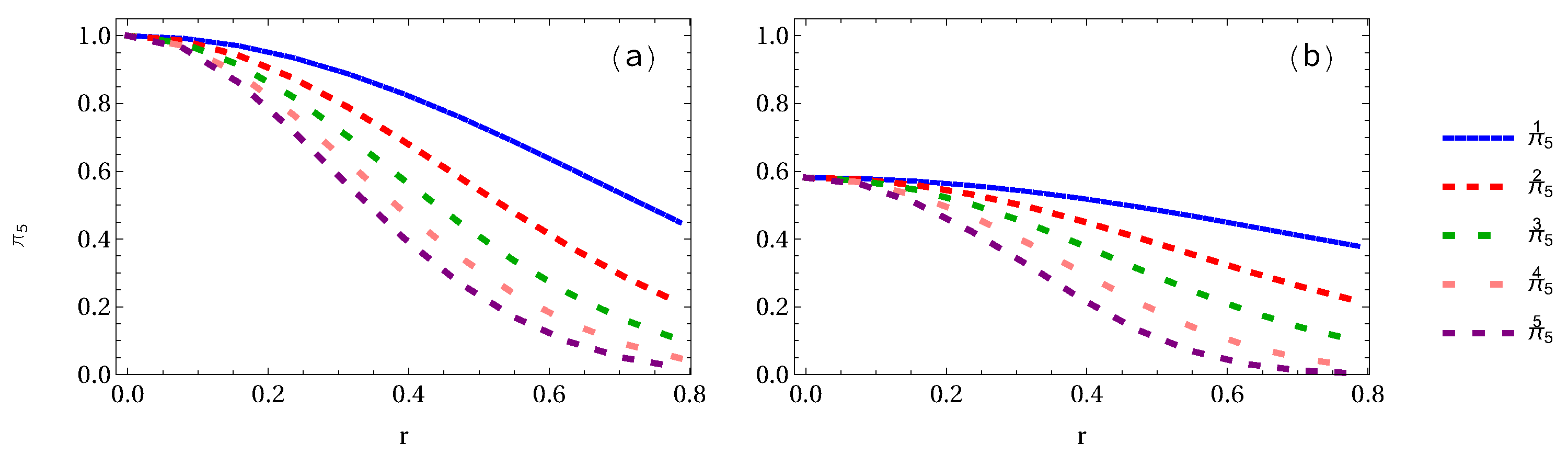

3.2. Whole Entanglement Measures

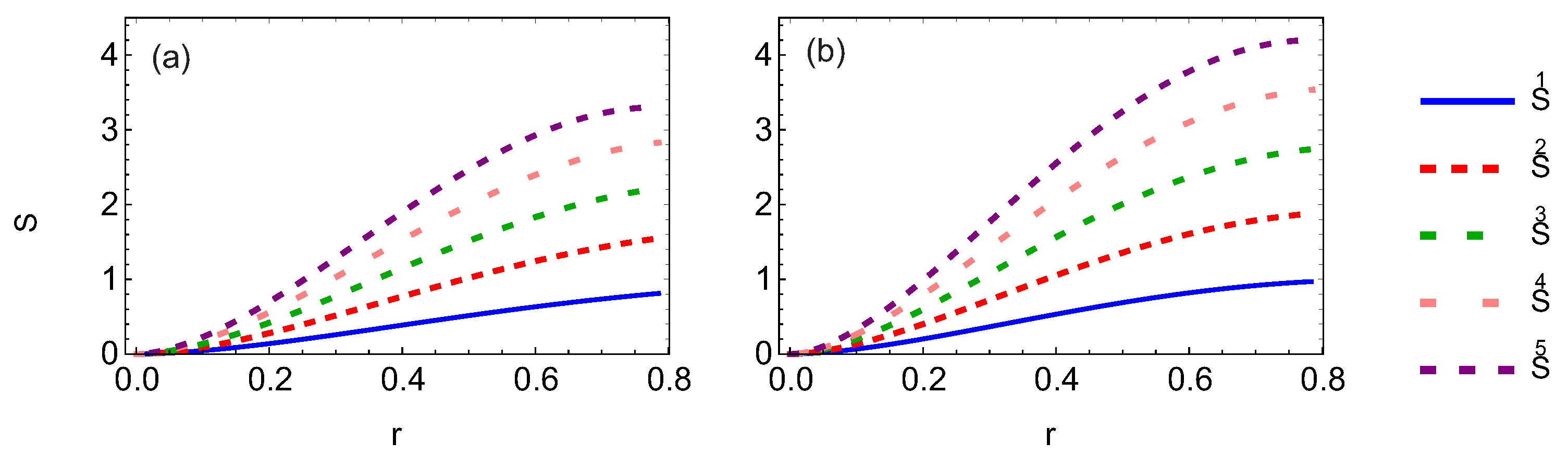

3.3. Entropy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Nonzero Elements of Density Matrices for GHZ and W-Class States in the Noninertial Frame

| Density Matrix | Nonzero Entries |

|---|---|

| Density Matrix | Nonzero Entries |

|---|---|

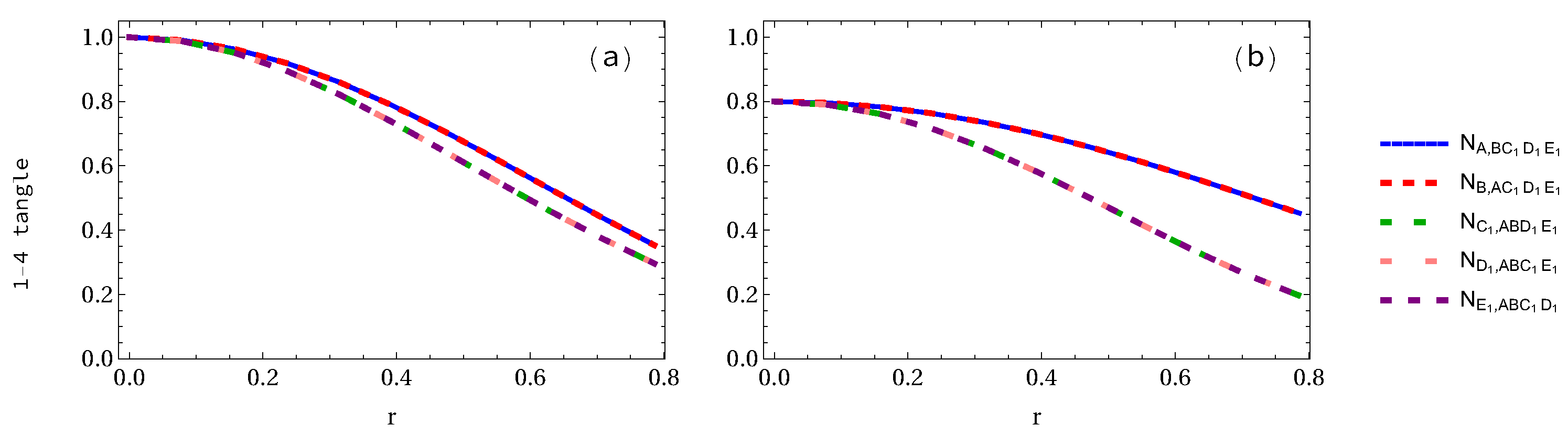

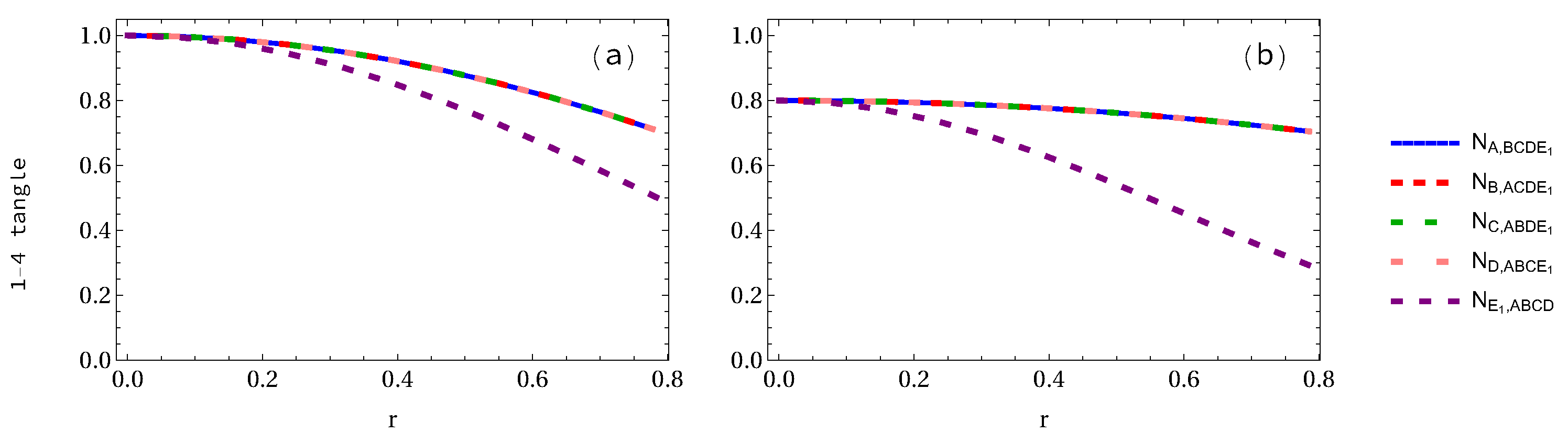

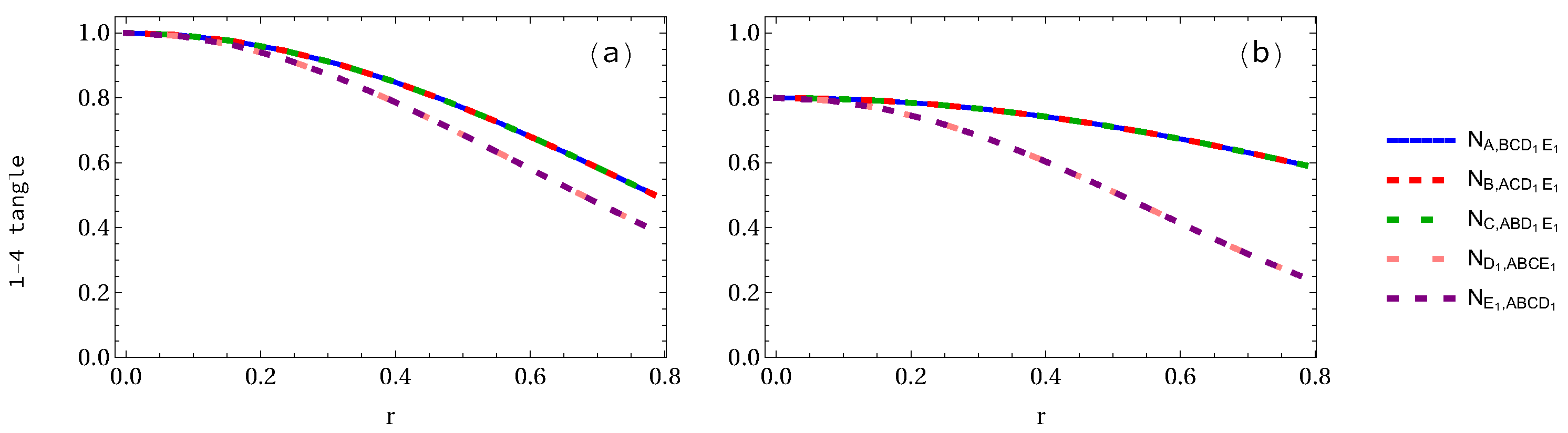

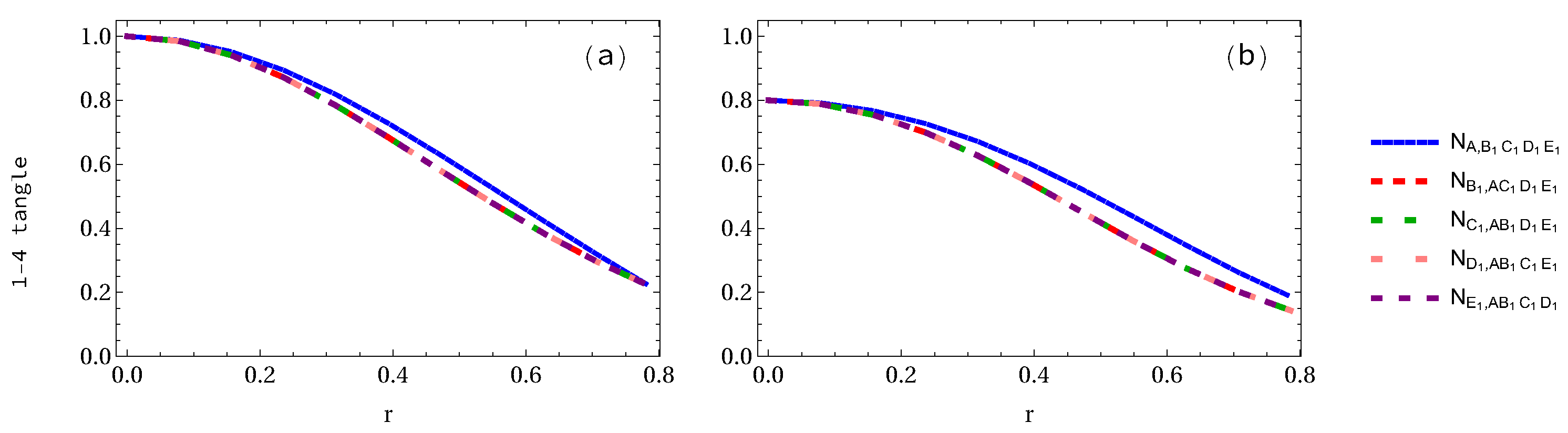

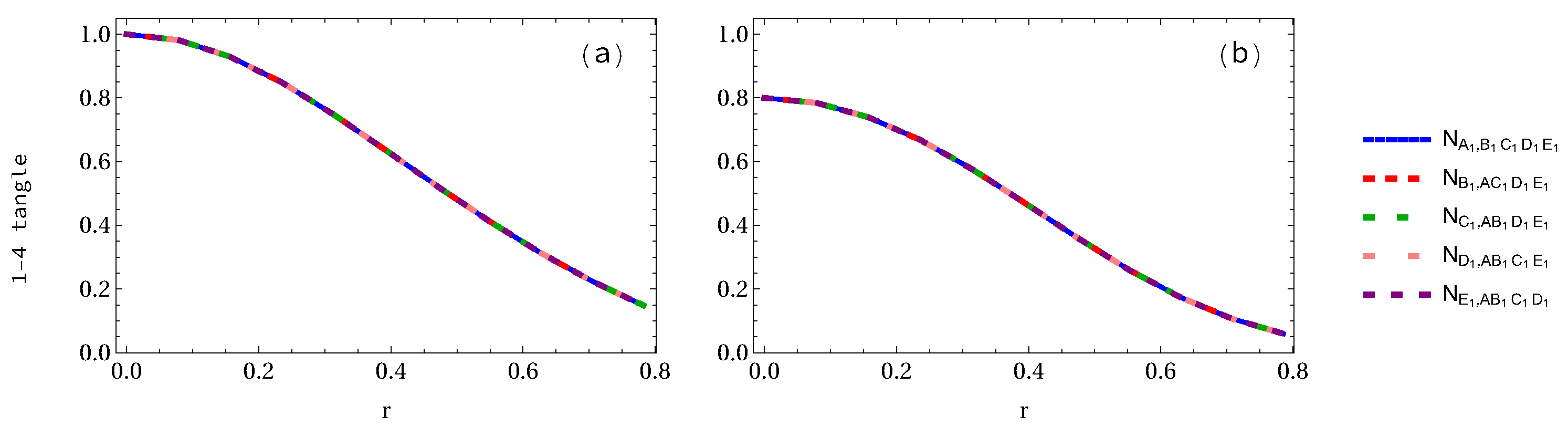

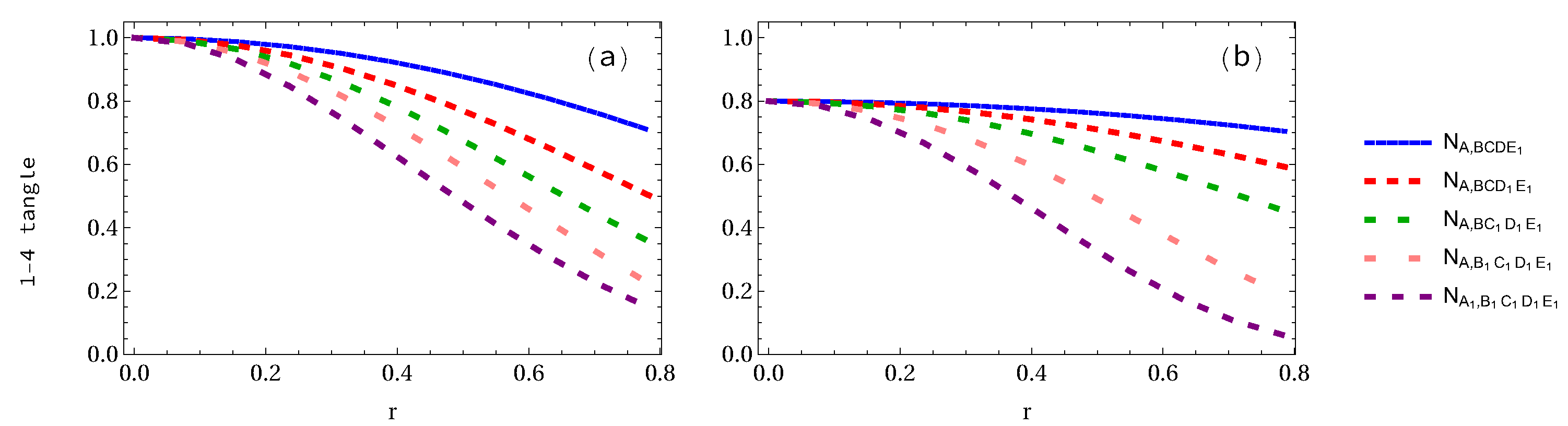

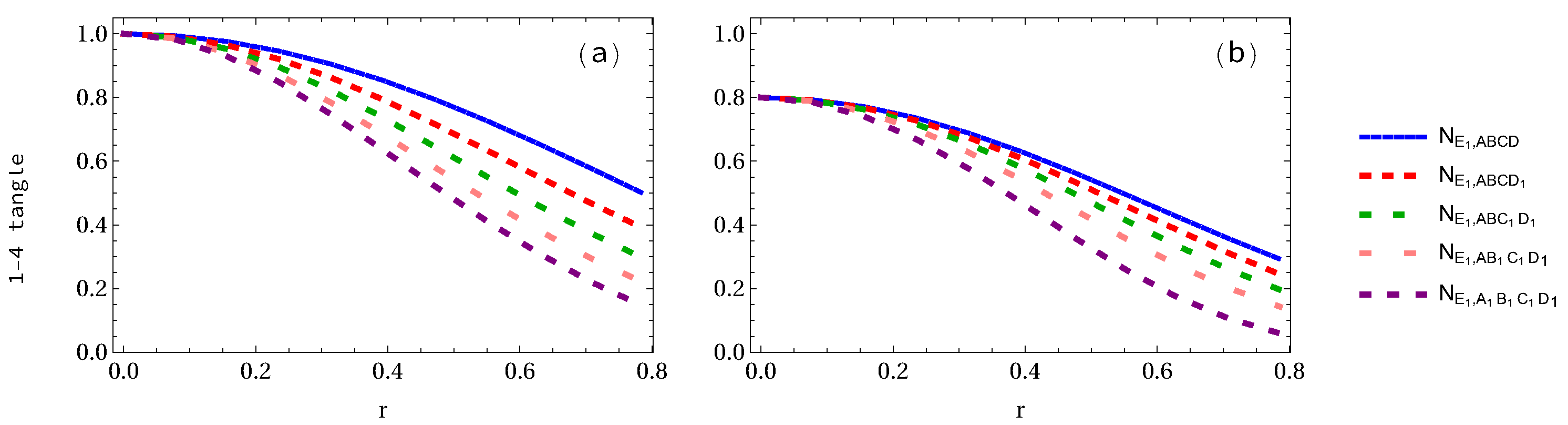

Appendix B. Analytical Expressions of 1-4 Tangles for GHZ and W-Class States

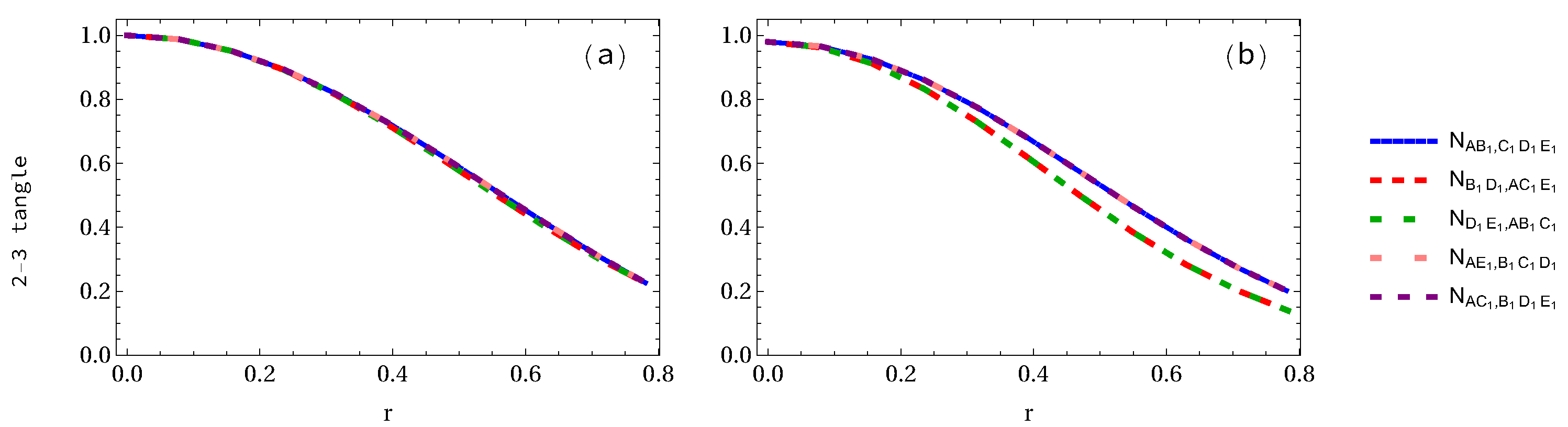

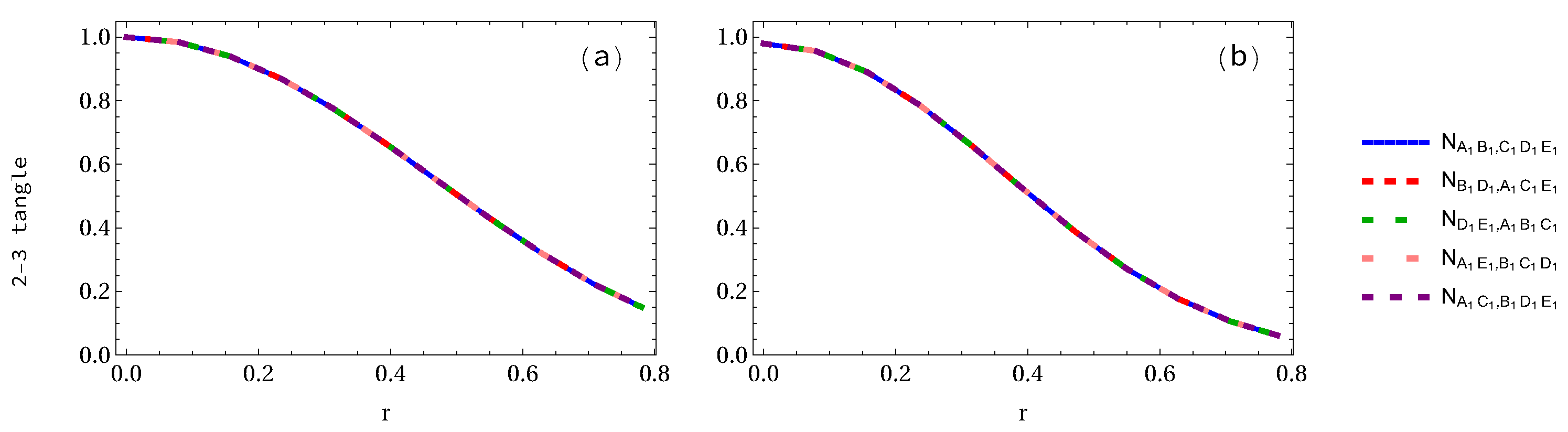

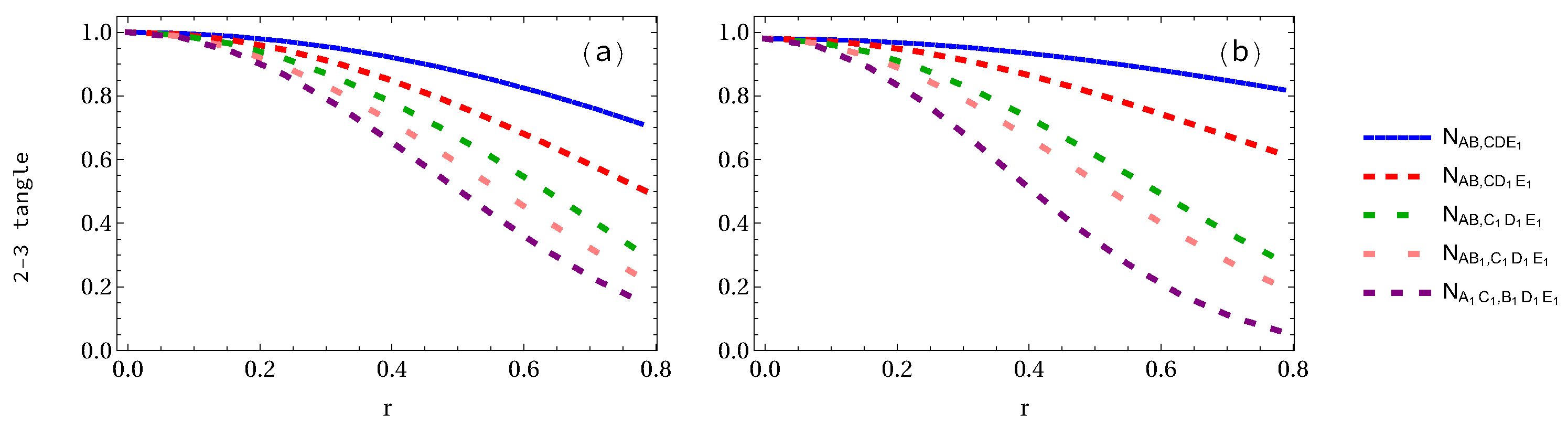

Appendix C. Analytical Expressions of 2-3 Tangles for GHZ and W-Class States

References

- Bennett, C.H.; Brassard, G.; Crépeau, C.; Jozsa, R.; Peres, A.; Wootters, W.K. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.H.; Bernstein, E.; Brassard, G.; Vazirani, U. Strengths and weaknesses of quantum computing. SIAM J. Comput. 1997, 26, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, D.; Ekert, A.; Zeilinger, A. The physics of quantum information: Basic concepts. In The Physics of Quantum Information; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.A.; Chuang, I.L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Phys. Today 2010, 54, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, C.A.; Gisin, N.; Griffiths, R.B.; Niu, C.S.; Peres, A. Optimal eavesdropping in quantum cryptography. I. Information bound and optimal strategy. Phys. Rev. A 1997, 56, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G. Efficient classical simulation of slightly entangled quantum computations. Quantum coherence and entanglement partitions for two driven quantum dots inside a coherent micro cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 147902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.B.A.; Eleuch, H.; Raymond Ooi, C.H. Quantum coherence and entanglement partitions for two driven quantum dots inside a coherent micro cavity. Phys. Lett. A 2019, 383, 125905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.B.A.; Eleuch, H. Coherence and information dynamics of a Λ-type three-level atom interacting with a damped cavity field. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2017, 132, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asjad, M.; Qasymeh, M.; Eleuch, H. Continuous-Variable Quantum Teleportation Using a Microwave-Enabled Plasmonic Graphene Waveguide. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2021, 16, 034046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleuch, H.; Rotter, I. Nearby states in non-Hermitian quantum systems I: Two states. Eur. Phys. J. D 2015, 69, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for Quantum Computation: Discrete Logarithms and Factoring. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 20–22 November 1994; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, L.K. Quantum Mechanics Helps in Searching for a Needle in a Haystack. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 79, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augusiak, R.; Horodecki, P. Multipartite secret key distillation and bound entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 042307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsing, P.M.; Milburn, G.J. Teleportation with a uniformly accelerated partner. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 180404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Jing, J. Multipartite entanglement of fermionic systems in noninertial frames. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 83, 022314, Erratum in Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 029902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsing, P.M.; Fuentes-Schuller, I.; Mann, R.B.; Tessier, T.E. Entanglement of Dirac fields in noninertial frames. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 74, 032326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, A.; Terno, D.R. Quantum information and relativity theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2004, 76, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispino, L.C.B.; Higuchi, A.; Matsa, G.E.A. The Unruh effect and its applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.C.W. Scalar production in Schwarzschild and Rindler metrics. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1975, 8, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, W.G. Notes on black-hole evaporation. Phys. Rev. D 1976, 14, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, D.E.; Louko, J.; Martín-Martínez, E.; Dragan, A.; Fuentes, I. Unruh effect in quantum information beyond the single-mode approximation. Phys. Rev. A 2010, 82, 042332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landulfo, A.G.S.; Matsas, G. Sudden death of entanglement and teleportation fidelity loss via the Unruh effect. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 032315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, W.C.; Sun, G.H.; Dong, Q.; Camacho-Nieto, O.; Dong, S.H. Concurrence of three Jaynes–Cummings systems. Quantum Inf. Process. 2018, 17, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, W.C.; Sun, G.H.; Dong, Q.; Dong, S.H. Genuine multipartite concurrence for entanglement of Dirac fields in noninertial frames. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 022320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.R.; Park, D.; Jung, E. Tripartite entanglement in a noninertial frame. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 83, 012111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xiao, X.; Ge, L.; Wang, X.G.; Sun, C.P. Quantum Fisher information in noninertial frames. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 89, 042336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S. Tripartite entanglement of fermionic system in accelerated frames. Ann. Phys. 2014, 348, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Khan, N.A.; Khan, M.K. Non-maximal tripartite entanglement degradation of Dirac and scalar fields in non-inertial frames. Commun. Theor. Phys. 2014, 61, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bruschi, D.E.; Dragan, A.; Fuentes, I.; Louko, J. Particle and antiparticle bosonic entanglement in noninertial frames. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 025026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martínez, E.; Fuentes, I. Redistribution of particle and antiparticle entanglement in noninertial frames. Phys. Rev. A 2011, 83, 052306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, N.; Lee, A.R.; Bruschi, D.E. Fermionic-mode entanglement in quantum information. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 022338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Mann, R.B. Persistence of tripartite nonlocality for noninertial observers. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 012306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradpour, H.; Maghool, S.; Moosavi, S.A. Three-particle Bell-like inequalities under Lorentz transformations. Quantum Inf. Process. 2015, 14, 3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moradi, S.; Amiri, F. Nonlocality and multipartite entanglement in asymptotically flat space-times. Commun. Theor. Phys. 2016, 65, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes-Schuller, I.; Mann, R.B. Alice falls into a black hole: Entanglement in noninertial frames. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Y.C.; Fan, H. Monogamy inequality in terms of negativity for three-qubit states. Phys. Rev. A 2007, 75, 062308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.K. Tripartite entanglement-dependence of tripartite non-locality in non-inertial frames. J. Phys. A 2012, 45, 415308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hwang, M.R.; Jung, E.; Park, D.K. Three-tangle in non-inertial frame. Class. Quant. Grav. 2012, 29, 224004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.K. Tripartite entanglement dynamics in the presence of Markovian or non-Markovian environment. Quantum Inf. Process. 2016, 15, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartzke, S.; Osterloh, A. Generalized W state of four qubits with exclusively the three-tangle. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 052307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.H.; Suter, D. Spin qubits for quantum simulations. Front. Phys. China 2010, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Arenas, A.J.; López-Zúñiga, E.O.; Saldaña-Herrera, J.A.; Dong, Q.; Sun, G.H.; Dong, S.H. Tetrapartite entanglement measures of W-class in noninertial frames. Chin. Phys. B 2019, 28, 070301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Arenas, A.J.; Dong, Q.; Sun, G.H.; Qiang, W.C.; Dong, S.H. Entanglement measures of W-state in noninertial frames. Phys. Lett. B 2019, 789, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Torres-Arenas, A.J.; Sun, G.H.; Dong, S.H. Tetrapartite entanglement features of W-Class state in uniform acceleration. Front. Phys. 2020, 15, 11602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Sánchez-Manilla, A.A.; López-Yáñez, I.; Sun, G.H.; Dong, S.H. Tetrapartite entanglement measures of GHZ state with uniform acceleration. Phys. Scr. 2019, 94, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Mercado Sanchez, M.A.; Sun, G.H.; Toutounji, M.; Dong, S.H. Tripartite entanglement measures of generalized GHZ state in uniform acceleration. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2019, 36, 100301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Sun, G.H.; Toutounji, M.; Dong, S.H. Tetrapartite entanglement measures of GHZ state with nonuniform acceleration. Optik 2020, 201, 163487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Santana Carrillo, R.; Sun, G.H.; Dong, S.H. Tetrapartite entanglement measures of generalized GHZ state in the noninertial frames. Chin. Phys. B 2022, 31, 030303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.Y.; Wang, D.; Yang, J.; Ye, L. Enhancement of multipartite entanglement in an open system under non-inertial frames. Quantum Inf. Process. 2017, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffman, V.; Kundu, J.; Wooters, W.K. Distributed entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 61, 052306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía Ocampo, D.; Salgado Ramírez, J.C.; Yáñez-Márquez, C.; Sun, G.H. Entanglement measures of a pentapartite W-class state in the noninertial frame. Quantum Inf. Process. 2022, 21, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Dür, W.; Vidal, G.; Cirac, J.I. Three qubits can be entangled in two inequivalent ways. Phys. Rev. A 2000, 62, 062314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socolovsky, M. Rindler space and Unruh effect. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1304.2833. [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara, M.; Wan, Y.; Sasaki, Y. Diversities in Quantum Computation and Quantum Information; World Scientific: Singapore, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Birrel, N.D.; Davies, P.C.W. Quantum Fields in Curved Space; Cambridge University: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Qiang, W.C.; Zhang, L. Geometric measure of quantum discord for entanglement of Dirac fields in noninertial frames. Phys. Lett. B 2015, 742, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Torres-Arenas, A.J.; Sun, G.H.; Qiang, W.C.; Dong, S.H. Entanglement measures of a new type pseudo-pure state in accelerated frames. Front. Phys. 2019, 14, 21603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehri-Dehnavi, H.; Mirza, B.; Mohammadzadeh, H.; Rahimi, R. Pseudo-entanglement evaluated in noninertial frames. Ann. Phys. 2011, 326, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukas, J.; Brown, E.G.; Dragan, A.; Mann, R.B. Entanglement and discord: Accelerated observations of local and global modes. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 012306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martínez, E.; Garay, L.J.; León, J. Unveiling quantum entanglement degradation near a Schwarzschild black hole. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 82, 064006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martínez, E.; Garay, L.J.; León, J. Quantum entanglement produced in the formation of a black hole. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 82, 064028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martínez, E.; Hosler, D.; Montero, M. Fundamental limitations to information transfer in accelerated frames. Phys. Rev. A 2012, 86, 062307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Doukas, J.; Martín-Martínez, E.; Edward Bruschi, D. Localized projective measurement of a quantum field in non-inertial frames. Class. Quantum Grav. 2013, 30, 235006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dragan, A.; Doukas, J.; Martín-Martínez, E. Localized detection of quantum entanglement through the event horizon. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 052326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsing, P.M.; Fuentes, I. Observer-dependent entanglement. Class. Quantum Grav. 2012, 29, 224001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Kim, J.S. Negativity and strong monogamy of multiparty quantum entanglement beyond qubits. Phys. Rev. A 2015, 92, 042307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G.; Werner, R.F. Computable measure of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 2002, 65, 032314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Hu, L. Tetrapartite entanglement of fermionic systems in noninertial frames. Optik 2016, 127, 9788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.P. Explorations in Quantum Computing; Springer Science and Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, D.S.; Ramos, R.V. Residual entanglement with negativity for pure four-qubit quantum states. Quantum Inf. Process. 2010, 9, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabín, C.; García-Alcaine, G. A classification of entanglement in three-qubit systems. Eur. Phys. J. D 2008, 48, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics; Princeton University Press: Princeto, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Popescu, S.; Rohrlich, D. Thermodynamics and the measure of entanglement. Phys. Rev. A 1997, 56, R3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, I.; Życzkowski, K. Geometry of Quantum States: An Introduction to Quantum Entanglement; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Density Matrix | Eigenvalues |

|---|---|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Manríquez Zepeda, J.L.; Rueda Paz, J.; Avila Aoki, M.; Dong, S.-H. Pentapartite Entanglement Measures of GHZ and W-Class State in the Noninertial Frame. Entropy 2022, 24, 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24060754

Manríquez Zepeda JL, Rueda Paz J, Avila Aoki M, Dong S-H. Pentapartite Entanglement Measures of GHZ and W-Class State in the Noninertial Frame. Entropy. 2022; 24(6):754. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24060754

Chicago/Turabian StyleManríquez Zepeda, Juan Luis, Juvenal Rueda Paz, Manuel Avila Aoki, and Shi-Hai Dong. 2022. "Pentapartite Entanglement Measures of GHZ and W-Class State in the Noninertial Frame" Entropy 24, no. 6: 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24060754

APA StyleManríquez Zepeda, J. L., Rueda Paz, J., Avila Aoki, M., & Dong, S.-H. (2022). Pentapartite Entanglement Measures of GHZ and W-Class State in the Noninertial Frame. Entropy, 24(6), 754. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24060754