Abstract

This paper introduces an upper bound on the absolute difference between: the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the sum of a finite number of independent and identically distributed random variables with finite absolute third moment; and a saddlepoint approximation of such CDF. This upper bound, which is particularly precise in the regime of large deviations, is used to study the dependence testing (DT) bound and the meta converse (MC) bound on the decoding error probability (DEP) in point-to-point memoryless channels. Often, these bounds cannot be analytically calculated and thus lower and upper bounds become particularly useful. Within this context, the main results include, respectively, new upper and lower bounds on the DT and MC bounds. A numerical experimentation of these bounds is presented in the case of the binary symmetric channel, the additive white Gaussian noise channel, and the additive symmetric -stable noise channel.

1. Introduction

This paper focuses on approximating the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of sums of a finite number of real-valued independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables with finite absolute third moment. More specifically, let , , ⋯, , with n an integer and , be real-valued random variables with probability distribution . Denote by the CDF associated with , and, if it exists, denote by the corresponding probability density function (PDF). Let also

be a random variable with distribution . Denote by the CDF and if it exists, denote by the PDF associated with . The objective is to provide a positive function that approximates and an upper bound on the resulting approximation error. In the following, a positive function is said to approximate with an approximation error that is upper bounded by a function , if, for all ,

The case in which , , ⋯, in (1) are stable random variables with analytically expressible is trivial. This is essentially because the sum follows the same distribution of a random variable , where and Y is a random variable whose CDF is . Examples of this case are random variables following the Gaussian, Cauchy, or Levy distributions [1].

In general, the problem of calculating the CDF of boils down to calculating convolutions. More specifically, it holds that

where . Even for discrete random variables and small values of n, the integral in (3) often requires excessive computation resources [2].

When the PDF of the random variable cannot be conveniently obtained but only the r first moments are known, with , an approximation of the PDF can be obtained by using an Edgeworth expansion. Nonetheless, the resulting relative error in the large deviation regime makes these approximations inaccurate [3].

When the cumulant generating function (CGF) associated with , denoted by , is known, the PDF can be obtained via the Laplace inversion lemma [2]. That is, given two reals and , if is analytic for all , then,

with and . Note that the domain of in (4) has been extended to the complex plane and thus it is often referred to as the complex CGF. With an abuse of notation, both the CGF and the complex CGF are identically denoted.

In the case in which n is sufficiently large, an approximation to the Bromwich integral in (4) can be obtained by choosing the contour to include the unique saddlepoint of the integrand as suggested in [4]. The intuition behind this lies on the following observations:

- (i)

- the saddlepoint, denoted by , is unique, real and ;

- (ii)

- within a neighborhood around the saddlepoint of the form , with and sufficiently small, and can be assumed constant; and

- (iii)

- outside such neighborhood, the integrand is negligible.

From , it follows that the derivative of with respect to t, with , is equal to zero when it is evaluated at the saddlepoint . More specifically, for all ,

and thus

which shows the dependence of on both x and n.

A Taylor series expansion of the exponent in the neighborhood of , leads to the following asymptotic expansion in powers of of the Bromwich integral in (4):

where is

and for all and , the notation represents the k-th real derivative of the CGF evaluated at t. The first two derivatives and play a central role, and thus it is worth providing explicit expressions. That is,

The function in (8) is referred to as the saddlepoint approximation of the PDF and was first introduced in [4]. Nonetheless, is not necessarily a PDF as often its integral on is not equal to one. A particular exception is observed only in three cases [5]. First, when is the PDF of a Gaussian random variable, the saddlepoint approximation is identical to , for all . Second and third, when is the PDF associated with a Gamma distribution and an inverse normal distribution, respectively, the saddlepoint approximation is exact up to a normalization constant for all .

An approximation to the CDF can be obtained by integrating the PDF in (4), cf., [6,7,8]. In particular, the result reported in [6] leads to an asymptotic expansion of the CDF of , for all , of the form:

where the function is the saddlepoint approximation of . That is, for all ,

where the function is the complementary CDF of a Gaussian random variable with zero mean and unit variance. That is, for all ,

Finally, from the central limit theorem [3], for large values of n and for all , a reasonable approximation to is . In the following, this approximation is referred to as the normal approximation of .

1.1. Contributions

The main contribution of this work is an upper bound on the error induced by the saddlepoint approximation in (12) (Theorem 3 in Section 2.2). This result builds upon two observations. The first observation is that the CDF can be written for all in the form,

where the random variable

has a probability distribution denoted by , and the random variables , , …, are independent with probability distribution . The distribution is an exponentially tilted distribution [9] with respect to the distribution at the saddlepoint . More specifically, the Radon–Nikodym derivative of the distribution with respect to the distribution satisfies for all ,

The second observation is that the saddlepoint approximation in (12) can be written for all in the form,

where is a Gaussian random variable with mean x, variance , and probability distribution . Note that the means of the random variable in (14) and in (17) are equal to , whereas their variances are equal to . Note also that, from (6), it holds that .

Using these observations, it holds that the absolute difference between in (14) and in (17) satisfies for all ,

A step forward (Lemma A1 in Appendix A) is to note that, when x is such that , then,

and when x is such that , it holds that

where and are the CDFs of the random variables and , respectively. The final result is obtained by observing that can be upper bounded using the Berry–Esseen Theorem (Theorem 1 in Section 2.1). This is essentially due to the fact that the random variable is the sum of n independent random variables, i.e., (15), and is a Gaussian random variable, and both and possess identical means and variances. Thus, the main result (Theorem 3 in Section 2.2) is that, for all ,

where

with

1.2. Applications

In the realm of information theory, the normal approximation has played a central role in the calculation of bounds on the minimum decoding error probability (DEP) in point-to-point memoryless channels, cf., [10,11]. Thanks to the normal approximation, simple approximations for the dependence testing (DT) bound, the random coding union bound (RCU) bound, and the meta converse (MC) bound have been obtained in [10,12]. The success of these approximations stems from the fact that they are easy to calculate. Nonetheless, easy computation comes at the expense of loose upper and lower bounds and thus uncontrolled approximation errors.

On the other hand, saddlepoint techniques have been extensively used to approximate existing lower and upper bounds on the minimum DEP. See, for instance, [13,14] in the case of the RCU bound and the MC bound. Nonetheless, the errors induced by saddlepoint approximations are often neglected due to the fact that calculating them involves a large number of optimizations and numerical integrations. Currently, the validation of saddlepoint approximations is carried through Monte Carlo simulations. Within this context, the main objectives of this paper are twofold: to analytically assess the tightness of the approximation of DT and MC bounds based on the saddlepoint approximation of the CDFs of sums of i.i.d. random variables; to provide new lower and upper bounds on the minimum DEP by providing a lower bound on the MC bound and an upper bound on the DT bound. Numerical experimentation of these bounds is presented for the binary symmetric channel (BSC), the additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channel, and the additive symmetric -stable noise (SS) channel, where the new bounds are tight and obtained at low computational cost.

2. Sums of Independent and Identically Distributed Random Variables

In this section, upper bounds on the absolute error of approximating by the normal approximation and the saddlepoint approximation are presented.

2.1. Error Induced by the Normal Approximation

Given a random variable Y, let the function be for all :

where and are defined in (23).

The following theorem, known as the Berry–Esseen theorem [3], introduces an upper bound on the approximation error induced by the normal approximation.

Theorem 1

(Berry–Esseen [15]). Let , , …, be i.i.d random variables with probability distribution . Let also be a Gaussian random variable with mean , variance , and CDF denoted by . Then, the CDF of the random variable =++…+, denoted by , satisfies

where the functions , and are defined in (9), (10), and (24).

An immediate result from Theorem 1 gives the following upper and lower bounds on , for all ,

The main drawback of Theorem 1 is that the upper bound on the approximation error does not depend on the exact value of a. More importantly, for some values of a and n, the upper bound on the approximation error might be particularly big, which leads to irrelevant results.

2.2. Error Induced by the Saddlepoint Approximation

The following theorem introduces an upper bound on the approximation error induced by approximating the CDF of in (1) by the function ×→ defined such that for all , a, ∈×,

where the function is the complementary CDF of the standard Gaussian distribution defined in (13). Note that is identical to , when is chosen to satisfy the saddlepoint . Note also that is the CDF of a Gaussian random variable with mean and variance , which are the mean and the variance of in (1), respectively.

Theorem 2.

Let , , …, be i.i.d. random variables with probability distribution and CGF . Let also be the CDF of the random variable =++…+. Hence, for all a∈ and for all , it holds that

where

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 2 is presented in Appendix A. ☐

This result leads to the following upper and lower bounds on , for all ,

with ∈.

The advantages of approximating by using Theorem 2 instead of Theorem 1 are twofold. First, both the approximation and the corresponding approximation error depend on the exact value of a. In particular, the approximation can be optimized for each value of a via the parameter . Second, the parameter in (29) can be optimized to improve either the upper bound in (31) or the lower bound in (32) for some . Nonetheless, such optimizations are not necessarily simple.

An alternative to the optimization on in (31) and (32) is to choose such that it minimizes . This follows the intuition that, for some values of a and n, the term is the one that influences the most the value of the right-hand side of (29). To build upon this idea, consider the following lemma.

Lemma 1.

Consider a random variable Y with probability distribution and CGF . Given , let the function be defined for all satisfying , with denoting the interior of the convex hull of , as follows:

where is defined in (30). Then, the function h is concave and for all ,

Furthermore,

where is the unique solution in θ to

with is defined in (9).

Proof.

The proof of Lemma 1 is presented in Appendix B. ☐

Given , the value of in (33) is the argument that minimizes the exponential term in (29). An interesting observation from Lemma 1 is that the maximum of h is zero, and it is reached when . In this case, , and thus, from (31) and (32), it holds that

where is the CDF defined in Theorem 1. Hence, the upper bound in (37) and the lower bound in (38) obtained from Theorem 2 are worse than those in (26) and (27) obtained from Theorem 1. In a nutshell, for values of a around the vicinity of , it is more interesting to use Theorem 1 instead of Theorem 2.

Alternatively, given that h is non-positive and concave, when =>, with sufficiently large, it follows that

with defined in (36). Hence, in this case, the right-hand side of (29) is always smaller than the right-hand side of (25). That is, for such values of a and n, the upper and lower bounds in (31) and (32) are better than those in (26) and (27), respectively. The following theorem leverages this observation.

Theorem 3.

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 3 is presented in Appendix C. ☐

An immediate result from Theorem 3 gives the following upper and lower bounds on , for all ,

The following section presents two examples that highlight the observations mentioned above.

2.3. Examples

Example 1

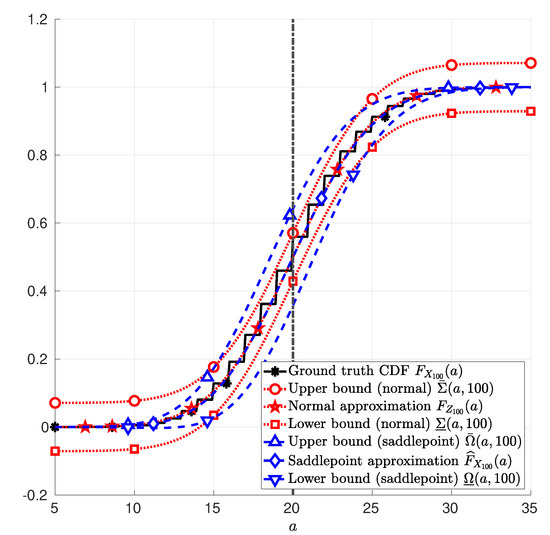

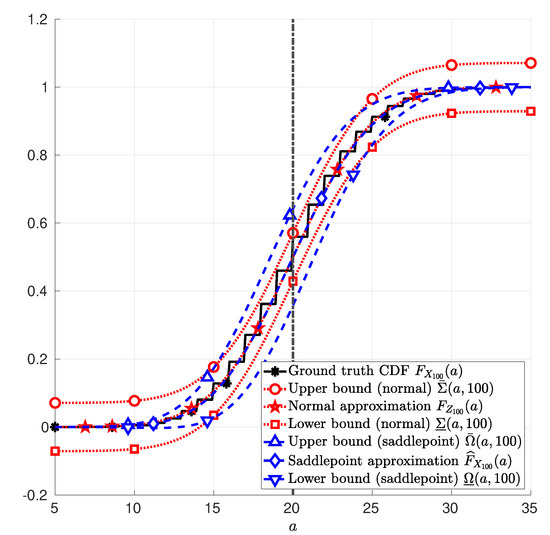

(Discrete random variable). Let the random variables , , …, in (1) be i.i.d. Bernoulli random variables with parameter and . In this case, . Figure 1 depicts the CDF of in (1); the normal approximation in (25); and the saddlepoint approximation in (12). Therein, it is also depicted the upper and lower bounds due to the normal approximation in (26) and in (27), respectively; and the upper and lower bounds due to the saddlepoint approximation in (41) and in (42), respectively. These functions are plotted as a function of a, with a∈.

Figure 1.

Sum of 100 Bernoulli random variables with parameter . The function (asterisk markers *) in Example 1; the function (star markers ⋆) in (25); the function (diamond markers ⋄) in (12); the function (circle marker ∘) in (26); the function (square marker □) in (27); the function (upward-pointing triangle marker ▵) in (41); and the function (downward-pointing triangle marker ▿) in (42) are plotted as functions of a, with .

Example 2

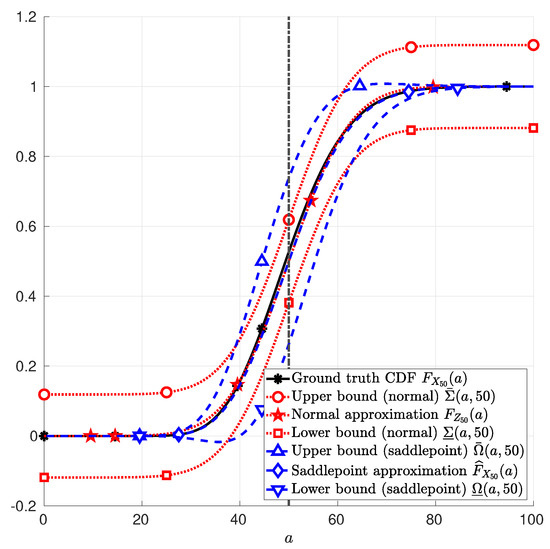

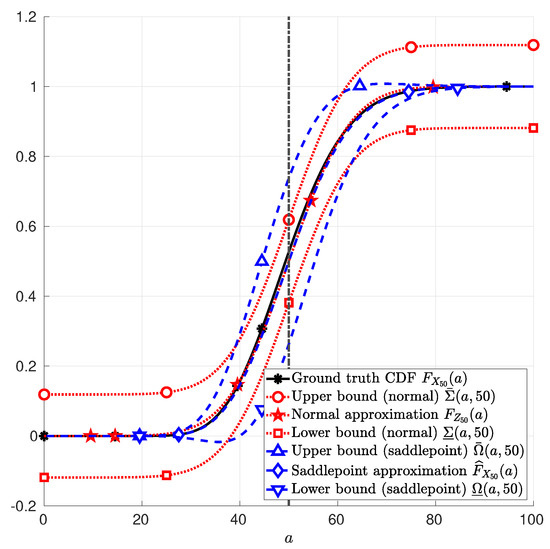

(Continuous random variable). Let the random variables , , …, in (1) be i.i.d. chi-squared random variables with parameter and . In this case, . Figure 2 depicts the CDF of in (1); the normal approximation in (25); and the saddlepoint approximation in (12). Therein, it is also depicted the upper and lower bounds due to the normal approximation in (26) and in (27), respectively; and the upper and lower bounds due to the saddlepoint approximation in (41) and in (42), respectively. These functions are plotted as a function of a, with a∈.

Figure 2.

Sum of 50 Chi-squared random variables with parameter . The function (asterisk markers *) in Example 2; the function (star markers ⋆) in (25); the function (diamond markers ⋄) in (12); the function (circle marker ∘) in (26); the function (square marker □) in (27); the function (upward-pointing triangle marker ▵) in (41); and the function (downward-pointing triangle marker ▿) in (42) are plotted as functions of a, with .

3. Application to Information Theory: Channel Coding

This section focuses on the study of the DEP in point-to-point memoryless channels. The problem is formulated in Section 3.1. The main results presented in this section consist of lower and upper bounds on the DEP. The former, which are obtained building upon the existing DT bound [10], are presented in Section 3.2. The latter, which are obtained from the MC bound [10], are presented in Section 3.3.

3.1. System Model

Consider a point-to-point communication in which a transmitter aims at sending information to one receiver through a noisy memoryless channel. Such a channel can be modeled by a random transformation

where is the blocklength and and are the channel input and channel output sets. Given the channel inputs =, , …, ∈, the outputs =, , …, ∈ are observed at the receiver with probability

where, for all , , with , the set of all possible probability distributions whose support is a subset of . The objective of the communication is to transmit a message index i, which is a realization of a random variable W that is uniformly distributed over the set

with 1 <M<∞. To achieve this objective, the transmitter uses an , M, -code, where ∈.

Definition 1

(, M,-code). Given a tuple , n, ∈×, an , M, -code for the random transformation in (43) is a system

where for all , with :

To transmit message index i∈, the transmitter uses the codeword . For all t∈{ 1,2,…, , at channel use t, the transmitter inputs the symbol into the channel. Assume that, at the end of channel use t, the receiver observes the output . After n channel uses, the receiver uses the vector =,,…, and determines that the symbol j was transmitted if ∈, with j∈.

Given the ,M,-code described by the system in (46), the DEP of the message index i can be computed as . As a consequence, the average DEP is

Note that, from (47d), the average DEP of such an -code is upper bounded by . Given a fixed pair ,∈, the minimum for which an ,M,-code exists is defined hereunder.

Definition 2.

Given a pair ,∈, the minimum average DEP for the random transformation in (43), denoted by , is given by

When is chosen accordingly with the reliability constraints, an -code is said to transmit at an information rate bits per channel use.

The remainder of this section introduces the DT and MC bounds. The DT bound is one of the tightest existing upper bounds on in (49), whereas the MC bound is one of the tightest lower bounds.

3.2. Dependence Testing Bound

This section describes an upper bound on , for a fixed pair . Given a probability distribution , let the random variable satisfy

where the function denotes the Radon–Nikodym derivative of the joint probability measure with respect to the product of probability measures , with and the corresponding marginal. Let the function be for all ,∈ and for all probability distributions ,

Using this notation, the following lemma states the DT bound.

Lemma 2

(Dependence testing bound [10]). Given a pair ,∈, the following holds for all , with respect to the random transformation in (43):

with the function T defined in (51).

Note that the input probability distribution in Lemma 2 can be chosen among all possible probability distributions to minimize the right-hand side of (52), which improves the bound. Note also that with some loss of optimality, the optimization domain can be restricted to the set of product probability distributions for which for all ∈,

with . Hence, subject to (44), the random variable in (50) can be written as the sum of i.i.d. random variables, i.e.,

This observation motivates the application of the results of Section 2 to provide upper and lower bounds on the function T in (51), for some given values and a given distribution for the random transformation in (43) subject to (44). These bounds become significantly relevant when the exact value of cannot be calculated with respect to the random transformation in (43). In such a case, providing upper and lower bounds on helps in approximating its exact value subject to an error sufficiently small such that the approximation is relevant.

3.2.1. Normal Approximation

This section describes the normal approximation of the function T in (51). That is, the random variable is assumed to satisfy (54) and to follow a Gaussian distribution. More specifically, for all , let

with and defined in (23), be functions of the input distribution . In particular, and are respectively the first moment and the second central moment of the random variables , …. Using this notation, consider the functions and such that for all and for all ,

where

Using this notation, the following theorem introduces lower and upper bounds on the function T in (51).

Theorem 4.

Proof.

In [12], the function in (60) is often referred to as the normal approximation of , which is indeed a language abuse. In Section 2.1, a comment is given on the fact that the lower and upper bounds, i.e., the functions D in (58) and N in (59), are often too far from the normal approximation in (60).

3.2.2. Saddlepoint Approximation

This section describes an approximation of the function T in (51) by using the saddlepoint approximation of the CDF of the random variable , as suggested in Section 2.2. Given a distribution , the moment generating function of is

with . For all and for all , consider the following functions:

where and are defined in (23). Using this notation, consider the functions and :

and

Note that is the saddlepoint approximation of the CDF of the random variable in (54) when and follow the distribution . Note also that is the saddlepoint approximation of the complementary CDF of the random variable in (54) when and follow the distribution .

Consider also the following functions:

where,

with in (66) and in (67). Often, the function in (72) is referred to as the saddlepoint approximation of the function T in (51), which is indeed a language abuse.

The following theorem introduces new lower and upper bounds on the function T in (51).

Theorem 5.

Given a pair , for all input distributions subject to (53), the following holds with respect to the random transformation in (43) subject to (44),

where θ is the unique solution in t to

and the functions T, G, and S are defined in (51), (70), and (71).

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 5 is provided in Appendix F. In a nutshell, the proof relies on Theorem 3 for independently bounding the terms and in (51). ☐

3.3. Meta Converse Bound

This section describes a lower bound on , for a fixed pair . Given two probability distributions and , let the random variable satisfy

For all ,M,∈ and for all probability distributions and , let the function be

Using this notation, the following lemma describes the MC bound.

Lemma 3

Note that the output probability distribution in Lemma 3 can be chosen among all possible probability distributions to maximize the right-hand side of (76), which improves the bound. Note also that, with some loss of optimality, the optimization domain can be restricted to the set of probability distributions for which for all ∈,

with . Hence, subject to (44), for all , the random variable in (76) can be written as the sum of the independent random variables, i.e.,

With some loss of generality, the focus is on a channel transformation of the form in (43) for which the following condition holds: The infimum in (77) is achieved by a product distribution, i.e., is of the form in (53), when the probability distribution satisfies (78). Note that this condition is met by memoryless channels such as the BSC, the AWGN and SS channels with binary antipodal inputs, i.e., input alphabets are of the form , with . This follows from the fact that the random variable is invariant of the choice of when the probability distribution satisfies (78) and for all ,

Under these conditions, the random variable in (76) can be written as the sum of i.i.d. random variables, i.e.,

This observation motivates the application of the results of Section 2 to provide upper and lower bounds on the function C in (76), for some given values and given distributions and . These bounds become significantly relevant when the exact value of cannot be calculated with respect to the random transformation in (43). In such a case, providing upper and lower bounds on helps in approximating its exact value subject to an error sufficiently small such that the approximation is relevant.

3.3.1. Normal Approximation

This section describes the normal approximation of the function C in (76), that is to say, the random variable is assumed to satisfy (81) and to follow a Gaussian distribution. More specifically, for all , let

with and defined in (23), be functions of the input and output distributions and , respectively. In particular, and are respectively the first moment and the second central moment of the random variables . Using this notation, consider the functions and such that, for all and for all and for all ,

where

Using this notation, the following theorem introduces lower and upper bounds on the function C in (76).

Theorem 6.

Proof.

The function in (87) is often referred to as the normal approximation of , which is indeed a language abuse. In Section 2.1, a comment is given on the fact that the lower and upper bounds on the normal approximation, i.e., the functions in (85) and in (86), are often too far from the normal approximation in (87).

3.3.2. Saddlepoint Approximation

This section describes an approximation of the function C in (76) by using the saddlepoint approximation of the CDF of the random variable , as suggested in Section 2.2. Given two distributions and , let the random variable satisfy

where is in (44). The moment generating function of is

with . For all and , and for all , consider the following functions:

where and are defined in (23). Using this notation, consider the functions and :

Note that and are the saddlepoint approximation of the CDF and the complementary CDF of the random variable in (81) when follows the distribution and , respectively. Consider also the following functions:

and

The function in (100) is referred to as the saddlepoint approximation of the function C in (76), which is indeed a language abuse.

The following theorem introduces new lower and upper bounds on the function C in (76).

Theorem 7.

Given a pair , for all input distributions subject to (53), for all output distributions subject to (81) such that for all , is absolutely continuous with respect to , for all , the following holds with respect to the random transformation in (43) subject to (44),

where θ is the unique solution in t to

and the functions C, , and are defined in (76), (98) and (99).

Proof.

The proof of Theorem 7 is provided in Appendix G. ☐

3.4. Numerical Experimentation

The normal and the saddlepoint approximations of the DT and MC bounds as well as their corresponding upper and lower bounds presented from Section 3.2.1 to Section 3.3.2 are studied in the cases of the BSC, the AWGN channel, and the SS channel. The latter is defined by the random transformation in (43) subject to (44) and for all :

where is a probability distribution satisfying for all ,

with . The reals and in (104) are parameters of the SS channel.

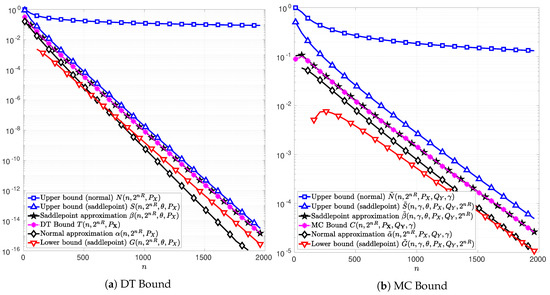

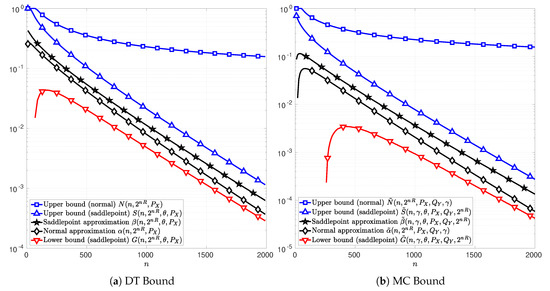

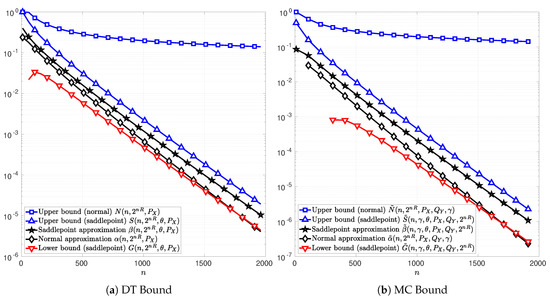

In the following figures, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5, the channel inputs are discrete , is the uniform distribution, and is chosen to be the unique solution to t in (74) or (102) depending on whether the DT or MC bound is considered. For the results relative to the MC bound, is chosen to be equal to the distribution , i.e., the marginal of . The parameter is chosen to maximize the function in (76). The plots in Figure 3a, Figure 4a and Figure 5a illustrate the function in (51) as well as the bounds in Theorems 4 and 5. Figure 3b, Figure 4b and Figure 5b illustrate the function C in (76) and the bounds in Theorems 6 and 7. The normal approximations, i.e, in (60) and in (87), of the DT and MC bounds, respectively, are plotted in black diamonds. The upper bounds, i.e., in (59) and in (86), are plotted in blue squares. The lower bounds of the DT and MC bounds, i.e., in (58) and in (85), are non-positive in these cases, and thus do not appear in the figures. The saddlepoint approximations of the DT and MC bounds, i.e., in (72) and in (100), respectively, are plotted in black stars. The upper bounds, i.e., in (71) and in (99), are plotted in blue upward-pointing triangles. The lower bounds, i.e., in (70) and in (98), are plotted in red downward-pointing triangles.

Figure 3.

Normal and saddlepoint approximations to the functions T (Figure 3a) in (51) and C (Figure 3b) in (76) as functions of the blocklength n for the case of a BSC with cross-over probability . The information rate is and bits per channel use for Figure 3a,b, respectively. The channel input distribution is chosen to be the uniform distribution, the output distribution is chosen to be the channel output distribution , and the parameter is chosen to maximize C in (76). The parameter is chosen to be respectively the unique solution to t in (74) in Figure 3a and in (102) in Figure 3b.

Figure 4.

Normal and saddlepoint approximations to the functions T (Figure 4a) in (51) and C (Figure 4b) in (76) as functions of the blocklength n for the case of a real-valued AWGN channel with discrete channel inputs, , signal to noise ratio , and information rate bits per channel use. The channel input distribution is chosen to be the uniform distribution, the output distribution is chosen to be the channel output distribution , and the parameter is chosen to maximize C in (76). The parameter is respectively chosen to be the unique solution to t in (74) in Figure 4a and in (102) in Figure 4b.

Figure 5.

Normal and saddlepoint approximation to the functions T (Figure 5a) in (51) and C (Figure 5b) in (76) as functions of the blocklength n for the case of a real-valued symmetric -stable noise channel with discrete channel inputs , shape parameter , dispersion parameter , and information rate bits per channel use. The channel input distribution is chosen to be the uniform distribution, the output distribution is chosen to be the channel output distribution , and the parameter is chosen to maximize C in (76). The parameter is respectively chosen to be the unique solution to t in (74) in Figure 5a and in (102) in Figure 5b.

Figure 3 illustrates the case of a BSC with cross-over probability . The information rates are chosen to be and bits per channel use in Figure 3a,b, respectively. The functions T and C can be calculated exactly and thus they are plotted in magenta asterisks in Figure 3a,b, respectively. In these figures, it can be observed that the saddlepoint approximations of the DT and MC bounds, i.e., and , respectively, overlap with the functions T and C. These observations are in line with those reported in [13]. Therein, the saddlepoint approximations of the RCU bound and the MC bound are both shown to be precise approximations. Alternatively, the normal approximations of the DT and MC bounds, i.e., and , do not overlap with T and C respectively.

In Figure 3, it can be observed that the new bounds on the DT and MC provided in Theorems 5 and 7, respectively, are tighter than those in Theorems 4 and 6. Indeed, the upper-bounds N and on the DT and MC bounds derived from the normal approximations and , are several order of magnitude above T and C, respectively. This observation remains valid for AWGN channels in Figure 4 and SS channels in Figure 5, respectively. Note that, in Figure 3a, for , the normal approximation is below the lower bound G showing that approximating T by is too optimistic. These results show that the use of the Berry–Esseen Theorem to approximate the DT and MC bounds may lead to erroneous conclusions due to the uncontrolled error made on the approximation.

Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the cases of a real-valued AWGN channel and a SS channel, respectively. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is for the AWGN channel. The information rate is bits per channel use for the AWGN channel and bits per channel use for the SS channel with . In both cases, the functions T in (51) and C in (76) can not be computed explicitly and hence does not appear in Figure 4 and Figure 5. In addition, the lower bounds and obtained from Theorems 4 and 6 are non-positive in these cases, and thus, do not appear on these figures.

In Figure 4, note that the saddlepoint approximations, and , are well bounded by Theorems 5 and 7 for a large range of blocklengths. Alternatively, the lower bounds D and based on the normal approximation do not even exist in that case.

In Figure 5, note that the upper bounds S and on the DT and MC respectively are relatively tight compared to those in AWGN channel case. This characteristic is of a particular importance in a channel such as SS channel, where the DT and MC bounds remain computable only by Monte Carlo simulations.

4. Discussion and Further Work

One of the main results of this work is Theorem 3, which gives an upper bound on the error induced by the saddlepoint approximation of the CDF of a sum of i.i.d. random variables. This result paves the way to study channel coding problems at any finite blocklength and any constraint on the DEP. In particular, Theorem 3 is used to bound the DT and MC bounds in point-to-point memoryless channels. This leads to tighter bounds than those obtained from Berry–Esseen Theorem (Theorem 1), cf., examples in Section 3.4, particularly for the small values of the DEP.

The bound on the approximation error presented in Theorem 2 uses a triangle inequality in the proof of Lemma A1, which is loose. This is essentially the reason why Theorem 2 is not reduced to the Berry–Esseen Theorem when the parameter is equal to zero. An interesting extension of this work is to tighten the inequality in Lemma A1 such that the Berry–Esseen Theorem can be obtained as a special case of Theorem 2, i.e., when . If such improvement on Theorem 2 is possible, Theorem 3 will be significantly improved and it would be more precise everywhere and in particular in the vicinity of the mean of the sum in (1).

Author Contributions

All authors have equally contributed to this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially funded by the French National Agency for Research (ANR) under grant ANR-16-CE25-0001.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Theorem 2

The proof of Theorem 2 relies on the notion of exponentially tilted distributions. Let be the moment generating function of the distribution . Given , let , , …, be random variables whose joint probability distribution, denoted by , satisfies for all ,

That is, the distribution is an exponentially tilted distribution with respect to . Using this notation, for all and for all ,

For the ease of the notation, consider the random variable

whose probability distribution is denoted by . Hence, plugging (A3) in (A2f) yields,

The proof continues by upper bounding the following absolute difference

where is a Gaussian random variable with the same mean and variance as , and probability distribution denoted by . The relevance of the absolute difference in (A5) is that it is equal to the error of calculating under the assumption that the resulting random variable follows a Gaussian distribution. The following lemma provides an upper bound on the absolute difference in (A5) in terms of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov distance between the distributions and , denoted by

where and are the CDFs of the random variables and , respectively.

Lemma A1.

Given and , consider the following conditions:

- (i)

- and , and

- (ii)

- and .

If at least one of the above conditions is satisfied, then the absolute difference in (A5) satisfies

Proof.

The proof of Lemma A1 is presented in Appendix D. ☐

The proof continues by providing an upper bound on in (A7) leveraging the observation that is the sum of n independent and identically distributed random variables. This follows immediately from the assumptions of Theorem 2, nonetheless, for the sake of completeness, the following lemma provides a proof of this statement.

Lemma A2.

For all , , , …, are mutually independent and identically distributed random variables with probability distribution . Moreover, is an exponential tilted distribution with respect to . That is, satisfies for all ,

Proof.

The proof of Lemma A2 is presented in Appendix E. ☐

Lemma A2 paves the way for obtaining an upper bound on in (A7) via the Berry–Esseen Theorem (Theorem 1). Let , , and be the mean, the variance, and the third absolute central moment of the random variable , whose probability distribution is in (A8). More specifically:

Let also be

with and defined in (23).

From Theorem 1, it follows that in (A7) satisfies:

Plugging (A13) in (A7) yields

under the assumption that at least one of the conditions of Lemma A1 is met.

The proof ends by obtaining a closed-form expression of the term ] in (A14) under the assumption that at least one of the conditions of Lemma A1 is met. First, assuming that condition in Lemma A1 holds, it follows that:

Second, assuming that condition in Lemma A1 holds, it follows that:

where Q in n (A15f) and (A16c) is the complementary CDF of the standard Gaussian distribution defined in (13).

The expressions in (A15f) and (A16c) can be jointly written as follows:

under the assumption that at least one of the conditions or in Lemma A1 holds.

Finally, under the same assumption, plugging (A17) in (A14) yields

Under condition in Lemma A1, the inequality in (A18) can be written as follows:

Alternatively, under condition in Lemma A1, it follows from (A18) that

Then, jointly writing (A19) and (A20), it follows that, for all and for all ,

which can also be written as

This completes the proof.

Appendix B. Proof of Lemma 1

Let be for all ,

First, note that for all and for all , the function g is a concave function of a. Hence, from the definition of the function h in (33), h is concave.

Second, note that given that . Hence, from (33), it holds that, for all ,

This shows that the function h in (33) is not positive.

Third, the next step of the proof consists of proving the equality in (35). For doing so, let be for all ,

Note that the function g is a convex in . This follows by verifying that its second derivative with respect to is positive. That is,

Hence, if the first derivative of g with respect to (see (A26a)) admits a zero in , then is the unique solution in to the following equality:

From (A28d), it follows that is the mean of a random variable that follows an exponentially tilted distribution with respect to . Thus, there exists a solution in for (A28d) if and only if —hence the equality in (35).

Finally, from (A28d), implies that . Hence, from (35). This completes the proof for .

Appendix C. Proof of Theorem 3

From Lemma 1, it holds that given such that ,

Then, plugging (A29) in the expression of , with function defined in (28), the following holds:

where equality in (A30d) follows (12). Finally, plugging (A30d) in (29) yields

This completes the proof by observing that is equivalent to .

Appendix D. Proof of Lemma A1

The left-hand side of (A7) satisfies

The focus is on obtaining explicit expressions for the terms and in (A32). First, consider the case in which the random variable is absolutely continuous and denote its probability density function by and its CDF by . Then,

Using integration by parts in (A33), under the assumption or in Lemma A1, the following holds:

Second, consider the case in which the random variable is discrete and denote its probability mass function by and its CDF by . Let the support of be , , …, , with . Assume that condition in Lemma A1 is satisfied. Then,

with , and

which is an expression of the same form as the one in (A34). Alternatively, assume that condition in Lemma A1 holds. Then,

with , and

which is an expression of the same form as those in (A34) and (A36m).

Note that, under the assumption that at least one of the conditions in Lemma A1 holds, the expressions in (A34), (A36m), and (A38k) can be jointly written as follows:

The expression in (A39) does not involve particular assumptions on the random variable other than being discrete or absolutely continuous. Hence, the same expression holds with respect to the random variable in (A32). More specifically,

where is the CDF of the random variable .

Finally, under the assumption that at least one of the conditions in Lemma A1 holds, then

Under the same assumption, the expressions in (A41g) and (A42b) can be jointly written as follows:

This concludes the proof of Lemma A1.

Appendix E. Proof of Lemma A2

In the case in which Y is discrete (, , denote probability mass functions) or absolutely continuous random variables (, , denote probability density functions), the following holds for all ,

and for all ,

Hence, , , …, are mutually independent and identically distributed. Moreover, for all ,

Appendix F. Proof of Theorem 5

For a fixed product probability input distribution in (53) and for the random transformation in (44), the upper bound in (51) can be written in the form of a weighted sum of the CDF and the complementary CDF of the random variables variables and that are sums of i.i.d random variables, respectively. That is,

where and with . More specifically, the function T in (51) can be rewritten in the form

where and are the CDFs of and , respectively.

The next step derives the upper and lower bounds on and by using the result of Theorem 3. That is,

where and satisfy

and for all ,

with and defined in (23); and for all

The next step simplifies the expressions on the right hand-side of (A54) and (A55) by studying the relation between and , and , and , and .

First, from (A57), using the change of measure from to because is absolutely continuous with respect to , it holds that

Then, from (A57) and (A58), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Second, from (A61), using the change of measure from to , it holds that

Then, from (A69) and (A71), it holds that

From (A62) and (A72), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Third, from (A56) and (A73), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Fourth, from (A63), using the change of measure from to , it holds that

From (A69), (A73), and (A76), it holds that

From (A64) and (A77), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Fifth, from (A59), using the change of measure from to , it holds that

From (A69), (A73), (A78), and (A80), it holds that

From (A60) and (A81), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Sixth, plugging (A69), (A73), and (A78) into (A65), for all , it holds that

Then, from (67) and (A83), it holds that

Then, plugging (A69), (A73), (A74), (A78), (A82), and (A84) into the right hand-side of (A54), it holds that

Alternatively, plugging (A69), (A73), (A74), (A78), (A82), and (A84) into the right hand-side of (A55), it holds that

where the equality in (A89) follows from (69). Observing that is a positive function, then from (A88), it holds that

Seventh, from (66) and (A65), it holds that

Then, plugging (A69), (A73), (A74), (A78), (A82), and (A91) into the right hand-side of (A52), it holds that

Alternatively, plugging (A69), (A73), (A74), (A78), (A82), and (A84) into the right hand-side of (A53), it holds that

where the equality in (A96) follows from (68). Observing that is a positive function, then, from (A95), it holds that

Finally, plugging (A86) and (A93) in (A51), it holds that

where the equality in (A99) follows from (72). Observing that , from (A99), it holds that

where the equality in (A96) follows from (71).

Alternatively, plugging (A89) and (A96) in (A51), it holds that

where the equality in (A96) follows from (71). Combining (A101) and (A103) concludes the proof.

Appendix G. Proof of Theorem 7

Note that, for given distributions subject (53), subject to (81), and for a random transformation in (43) subject to (44), the lower bound ,M,,, in (76) can be written in the form of a weighted sum of the CDF and the complementary CDF of the random variables variables and that are sums of i.i.d random variables, respectively. That is,

where and with . More specifically, the function C in (76) can be written in the form

where and are the CDFs of the random variables and , respectively.

The next step derives the upper and lower bounds on and by using the result of Theorem 3. That is,

and

where and satisfy

and for all

with and defined in (23); and for all

The next step simplifies the expressions on the right hand-side of (A109) and (A110) by studying the relation between and , and , and , and when the is absolutely continuous with respect to .

First, from (A112), using the change of measure from to because is absolutely continuous with respect to , it holds that

Then, from (A112) and (A113), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Second, from (A116), using the change of measure from to , it holds that

Then, from (A124) and (A126), it holds that

From (A117) and (A127), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Third, from (A111) and (A128), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Fourth, from (A118), using the change of measure from to , it holds that

From (A124), (A128), and (A131), it holds that

From (A119) and (A132), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Fifth, from (A114), using the change of measure from to , it holds that

From (A124), (A128), (A133), and (A135), it holds that

From (A115) and (A136), it holds that

This concludes the relation between and .

Sixth, plugging (A124), (A128), and (A133) into (A120), for all , it holds that

Then, from (95) and (A138), it holds that

Then, plugging (A124), (A128), (A129), (A133), (A137), and (A139) into the right hand-side of (A109), it holds that

Alternatively, plugging (A124), (A128), (A129), (A133), (A137), and (A139) into the right hand-side of (A110), it holds that

where the equality in (A144) follows from (97). Observing that is a positive function, then, from (A143), it holds that

Then, plugging (A124), (A128), (A129), (A133), (A137), and (A146) into the right hand-side of (A107), it holds that

Alternatively, plugging (A124), (A128), (A129), (A133), (A137), and (A139) into the right hand-side of (A108), it holds that

where the equality in (A151) follows from (96). Observing that is a positive function, then from (A150), it holds that

Finally, plugging (A141) and (A148) in (A106), it holds that

where the equality in (A150) follows from (100). Observing that , from (A153), it holds that

where (A156) follows from (99).

Alternatively, plugging (A144) and (A151) in (A106), it holds that

where the equality in (A158) follows from (98). Combining (A156) and (A158) concludes the proof.

References

- Zolotarev, V.M. One-Dimensional Stable Distributions; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J.L. Saddlepoint Approximations; Clarendon Press—Oxford: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Feller, W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1971; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, H.E. Saddlepoint Approximations in Statistics. Ann. Math. Stat. 1954, 25, 631–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, H.E. Exact saddlepoint approximations. Biometrika 1980, 67, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, H.E. Tail Probability Approximations. Int. Stat. Rev./Rev. Int. Stat. 1987, 55, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temme, N. The Uniform Asymptotic Expansion of a Class of Integrals Related to Cumulative Distribution Functions. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1982, 13, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lugannani, R.; Rice, S. Saddle Point Approximation for the Distribution of the Sum of Independent Random Variables. Adv. Appl. Probab. 1980, 12, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esscher, F. On the probability function in the collective theory of risk. Skand. Aktuarie Tidskr. 1932, 15, 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Polyanskiy, Y.; Poor, H.V.; Verdú, S. Channel Coding Rate in the Finite Blocklength Regime. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2010, 56, 2307–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MolavianJazi, E.; Laneman, J.N. A Second-Order Achievable Rate Region for Gaussian Multi-Access Channels via a Central Limit Theorem for Functions. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2015, 61, 6719–6733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MolavianJazi, E. A Unified Approach to Gaussian Channels with Finite Blocklength. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Font-Segura, J.; Vazquez-Vilar, G.; Martinez, A.; Guillén i Fàbregas, A.; Lancho, A. Saddlepoint approximations of lower and upper bounds to the error probability in channel coding. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Conference on Information Sciences and Systems (CISS), Princeton, NJ, USA, 21–23 March 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, A.; Scarlett, J.; Dalai, M.; Guillén i Fàbregas, A. A complex-integration approach to the saddlepoint approximation for random-coding bounds. In Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Wireless Communications Systems (ISWCS), Barcelona, Spain, 26–29 August 2014; pp. 618–621. [Google Scholar]

- Shevtsova, I. On the absolute constants in the Berry–Esseen type inequalities for identically distributed summands. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1111.6554. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).