2.2. Bayesian Statistics

Suppose that any point

y of a smooth manifold

M equipped with a volume form

presents a positive probability density or probability

defined on a (possibly discrete) measurable space

W, where

depends smoothly on

y, and

for

. Let

be the space of positive volume forms with finite total volume on

M. Take an arbitrary element

and consider it as the initial state of the mind

M of an agent. Here

W stands for (a part of) the world for the agent. Finding a datum

in his world, the agent can take the value

as a smooth positive function

on

M, which is called the likelihood of the datum

w. Then, he can multiply the volume form

V by

to obtain a new element of

. This defines the updating map

The “psychological” probability density

on the mind

M defined by

is accordingly updated into the density

, which is called the conditional probability density given the datum

w. Practically, Bayes’ rule on conditional probabilities is expressed as

Here

P denotes the probability of an event,

(respectively,

) a small portion of

M (respectively,

W). Since the state of the world does not depend on the mind of the agent, the probability

is independent of

y, and therefore approximates a constant on

M. On the other hand, the conditional probability

of the datum

w approximates a function of

y which is clearly proportional to the above likelihood. This implies that the factor

in the right-hand side of Bayes’ rule (Equation (

4)) is approximately proportional to the likelihood. Thus, Bayes’ rule (Equation (

4)) implies the updating of

via the formula (Equation (

3)). The Bayesian product · mentioned in the introduction appears in this context. Namely, the variable of the first factor is the mean

y of a normal distribution on

W. The density of the normal distribution at the datum

w can be considered as a function of

y, which is proportional to a normal distribution on

M. Thus the Bayesian product of normal distributions on

M presents the updating of the density of the predictive mean in the mind of the agent.

The aim of Bayesian updating is practical to many people. Indeed, the aim of the above updating is the estimation of the mean. Nevertheless, it is quite natural that a geometer multiplies a volume form by a positive function once he is given them. In this regard, we can say that the aim of Bayesian updating is a geometric setting of a dynamical system. In particular, a Bayesian updating in the conjugate prior is at first, simply the iteration of a Bayesian product.

2.3. The Information Geometry

Suppose that a manifold

U is embedded in the subset

. Hereafter, we identify the element

with the “psychological” probability density

. We call

U a conjugate prior for the updating map

if the cone

satisfies

. (Whether there exists a preferred conjugate prior or not, how to determine the initial state of the mind is another interesting problem. For example, one may fix the asymptotic behavior of the state of mind according to the aim of the Bayesian inference and search for the optimal decision of the initial state. See [

7] for an approach to this problem via the information geometry.)

Now we define the “distance”

on

, which satisfies none of the axioms of distance, by

From the convexity of

, we see that the restriction

is a separating premetric on

U, which is called the Kullback–Leibler divergence in information theory. This implies that the germ of

D along the diagonal set

of

represents the zero section of the cotangent sheaf of

U, that is, for any point

of any chart of

U, the Taylor expansion of

has no linear terms. Thus the differential

also vanishes on the diagonal set

of

. We regard the 1-form on

represented by the germ of

along

as a quadratic tensor, and denote it by

g (note that

is linear). It appears as two times the quadratic terms

(

) in the above Taylor expansion. Of course, it also appears in the Taylor expansion of

. Thus it can also be considered as the quadratic terms of the symmetric sum

. The symmetric matrix

is called the Fisher information in information theory. From the non-negativity of

D, we may assume generically that

g is a Riemannian metric. We would like to notice that this construction of Riemannian metric by means of symmetric sum also works over

. Indeed, we have

Let

be the Levi–Civita connection of

g. We write the lowest degree terms in the Taylor expansions of

as

(

). This presents the symmetric cubic tensor

T, which can be constructed from the anti-symmetric difference

similarly as above. One can use it to deform the Levi–Civita connection

into the

-connections

(

) without torsion, where

denotes the dual metric. Especially, we call

and

respectively the e-connection and the m-connection. The symmetric tensor

T is sometimes called skewness since it presents the asymmetry of

D. The information geometry concerns the family of

-connections as well as the Fisher information metric on

U. We usually do not extend it over

for the symmetric sum of

lacks asymmetry.

2.5. The Generalization

This subsection is devoted to the generalization of the result of the author, which is mentioned in the introduction, to the above multivariate setting. We fix the third component r of the coordinate system , and change the presentation of the others. Namely, we take the natural projection and replace the coordinates on the fiber by appearing in the next proposition. The generalization is then straightforward.

Proposition 1. The fiber is an affine subspace of U with respect to the e-connection . It can be parameterized by affine parameters and , where and .

Proof. The natural parameters and are affine provided that are constant, and and are affine. □

Note that is identically zero on some/any fiber if and only if . The fiber satisfies the following two properties.

Proposition 2. is closed under the convolution ∗ and the Bayesian product ·, and thus inherits them.

Proof. The covariance of the density at

is

This coincides with that of the density at . Thus is closed under ∗, and inherits it as

Put and . The density at is proportional to . From this we see that implies , and . Thus is closed under ·, and inherits it as . □

Proposition 3. The fiber with the induced metric from g admits a Kähler complex structure.

Proof. The restriction of g is . We define the complex structure by (). Then, the 2-form satisfies . □

We write the restriction

of the premetric

D using the coordinates

as follows, where we omit

r for the expression does not depend on

r.

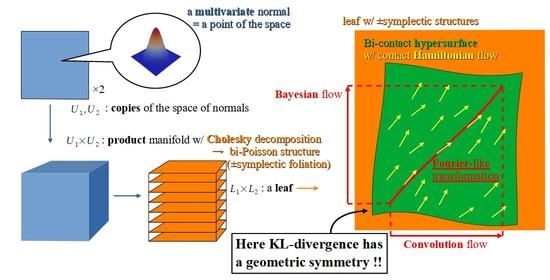

We take the product of two copies of U. Then, the products of the fibers foliate . We call this the primary foliation of . For each , we have the coordinate system on the leaf . From the Kähler forms and respectively on and , we define the symplectic forms on , which induce the mutually opposite orientations in the case where n is odd. Hereafter, we consider the pair of regular Poisson structures defined by these symplectic structures on the primary foliation, and fix the primitive 1-forms . The corresponding pair of Poisson bi-vectors is defined on . We take the -dimensional submanifolds of the leaf for and . The secondary foliation of foliates any leaf by the -dimensional submanifolds for . The tertiary foliation of foliates all leaves of the secondary foliation by the -dimensional submanifolds for .

Proposition 4. With respect to the Kähler form , the tertiary leaves are Lagrangian correspondences.

Proof. The tangent space is generated by and . We have and . Thus are Lagrangian submanifolds of . □

The restrictions of to the hypersurface are contact forms. Let denote them.

Proposition 5. For any ε and δ with , the submanifold is a disjoint union of n-dimensional submanifolds which are integral submanifolds of the hyper plane field on N.

Proof. We have . □

For each point

, we have the diffeomorphism

sending

to

with

. We put

and

Then, we have . For any , we define the diffeomorphism which preserves the 1-forms . It is easy to prove the following proposition.

Proposition 6. In the case where for , the diffeomorphism preserves .

For each , we take the set , and consider it as a structure of the secondary leaf .

Proposition 7. For any , the diffeomorphism preserves the set for any . In the case where ζ satisfies , the diffeomorphism also preserves the hypersurface N.

Proof. maps to , and holds. Further implies provided that . □

For any , the diffeomorphism interchanges the operation with the operation .

Proposition 8. If , then Proof. Putting we have and , hence the first equation. The second equation is similarly proved. □

A curve is a geodesic with respect to the e-connection if and only if and are affine functions of t for .

Definition 1. We say that an e-geodesic is intensive if it admits an affine parameterization such that are linear for .

Note that any e-geodesic is intensive in the case where .

Proposition 9. Given an intensive e-geodesic , we can change the parameterization of its image under the diffeomorphism to obtain an intensive e-geodesic.

Proof. Put and . We have and . They are respectively an affine function and a linear function of . □

We have the hypersurface which carries the contact forms . This is defined on any leaf of the primary foliation of . Now we state the main result.

Theorem 1. The contact Hamiltonian vector field Y of the restriction of the function to N for the contact form coincides with that for the other contact form . It is tangent to the tertiary leaves and defines flows on them. Here each flow line presents the correspondence between intensive e-geodesics in Proposition 9.

Corollary 1. For any , the flow on the leaf presents the iteration of the operation ∗ on the first factor of and that of the operation · on the second factor as is described in Proposition 8 (see Figure 1). From Corollary 1, we see that the flow model of Bayesian inference studied in [

4,

5] also works for the multivariate case. We prove the theorem.

Proof. Take the vector field on . It satisfies , , and , and thus its restriction to N is the contact Hamiltonian vector field Y. It also satisfies (), where the right-hand sides vanish along . Given a point , we have the integral curve of Y with initial point . We can change the parameter of the curve on the first factor with to obtain an intensive e-geodesic. □

2.6. The Symmetry

The diffeomorphism

with

in Proposition 7 also appears in the standard construction of Hilbert modular cusps in [

8]. We sketch the construction.

Since the function is linear in the logarithmic space , we can take points () so that the quotient of the primary leaf under the -action generated by , ..., is the total space of a vector bundle over . Here is the quotient of under the -lattice generated by the above points, and the fiber consists of the vectors .

In the univariate case (), on the logarithmic -plane, we can take any point of the line other than the origin. That is, we put and (). Then, the map sends to . The -action generated by it rolls up the level sets of H, so that the quotient of the logarithmic -plane becomes the cylinder , which is the base space. On the other hand, the -plane, which is the fiber, expands horizontally and contracts vertically. This is the inverse monodromy along . In general, we obtain a similar -bundle over if we take the points of in general position.

From Proposition 7, we see that the leaf

of the secondary foliation with the set

, as well as the pair of the 1-forms

with the function

H, descends to the

-bundle. If there exists further a

-lattice on the fiber

which is simultaneously preserved by the maps

(

), we obtain a

-bundle over

. Such a choice of

would be number theoretical. Indeed, this is the case for Hilbert modular cusps. Moreover, we are considering the 1-forms

, which descend to the

-bundle. See [

9] for the standard construction with special attention to these 1-forms.

We should notice that the vector field Y does not descend to the -bundle. However, every actual Bayesian inference along Y eventually stops. Thus, we may take sufficiently large and consider Y as a locally supported vector field to perform the inference in the quotient space.