Variational Autoencoder Reconstruction of Complex Many-Body Physics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Transverse-Field Ising Model

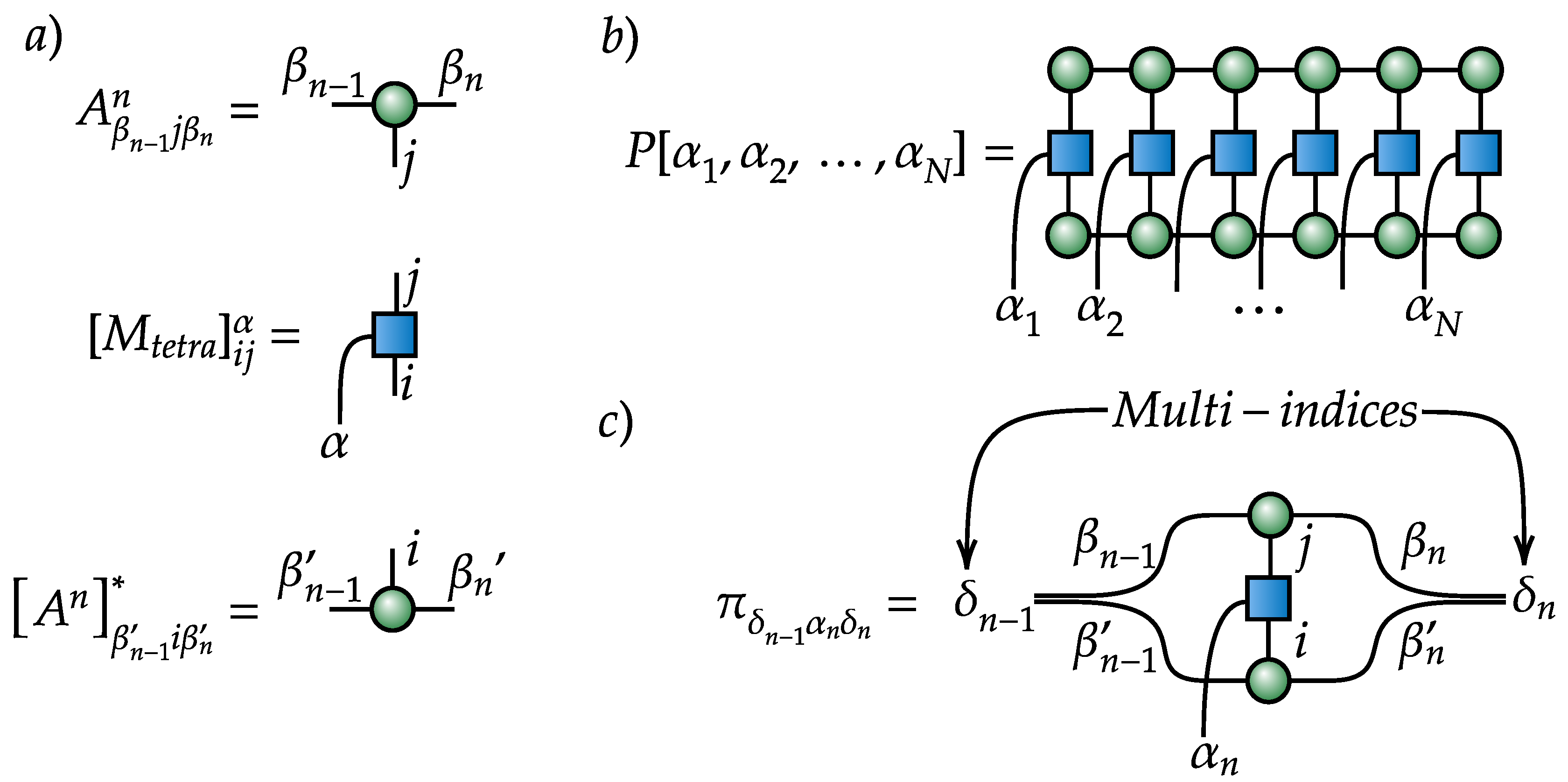

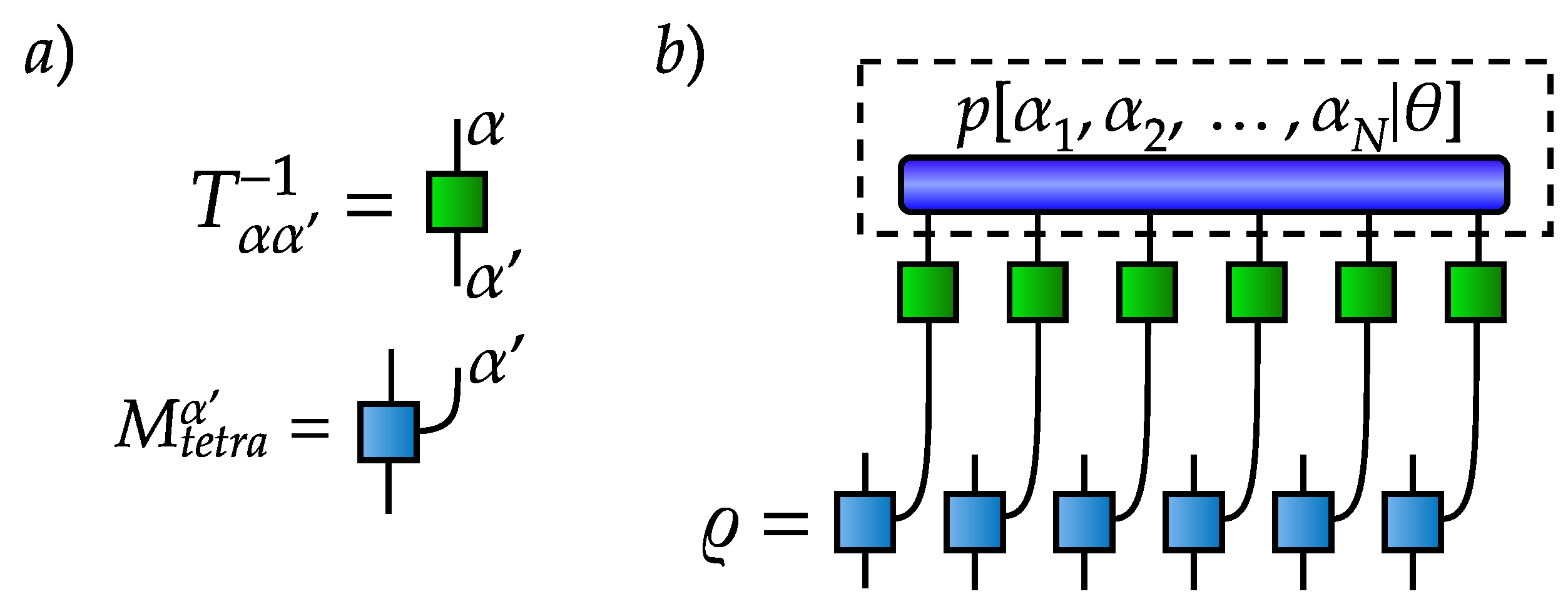

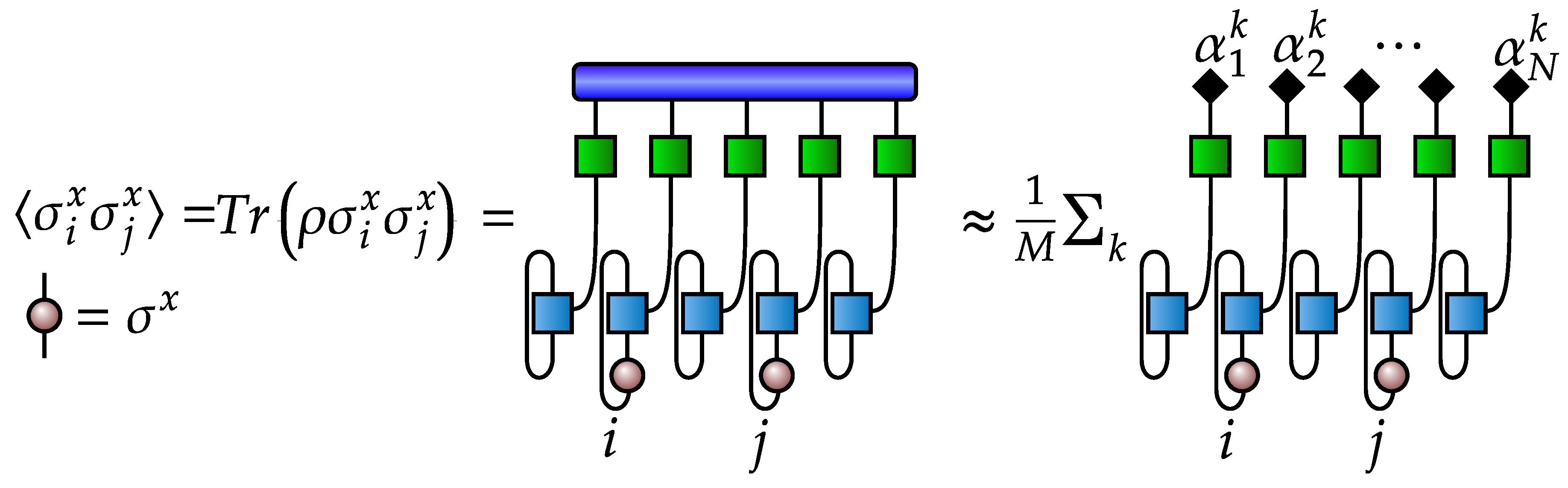

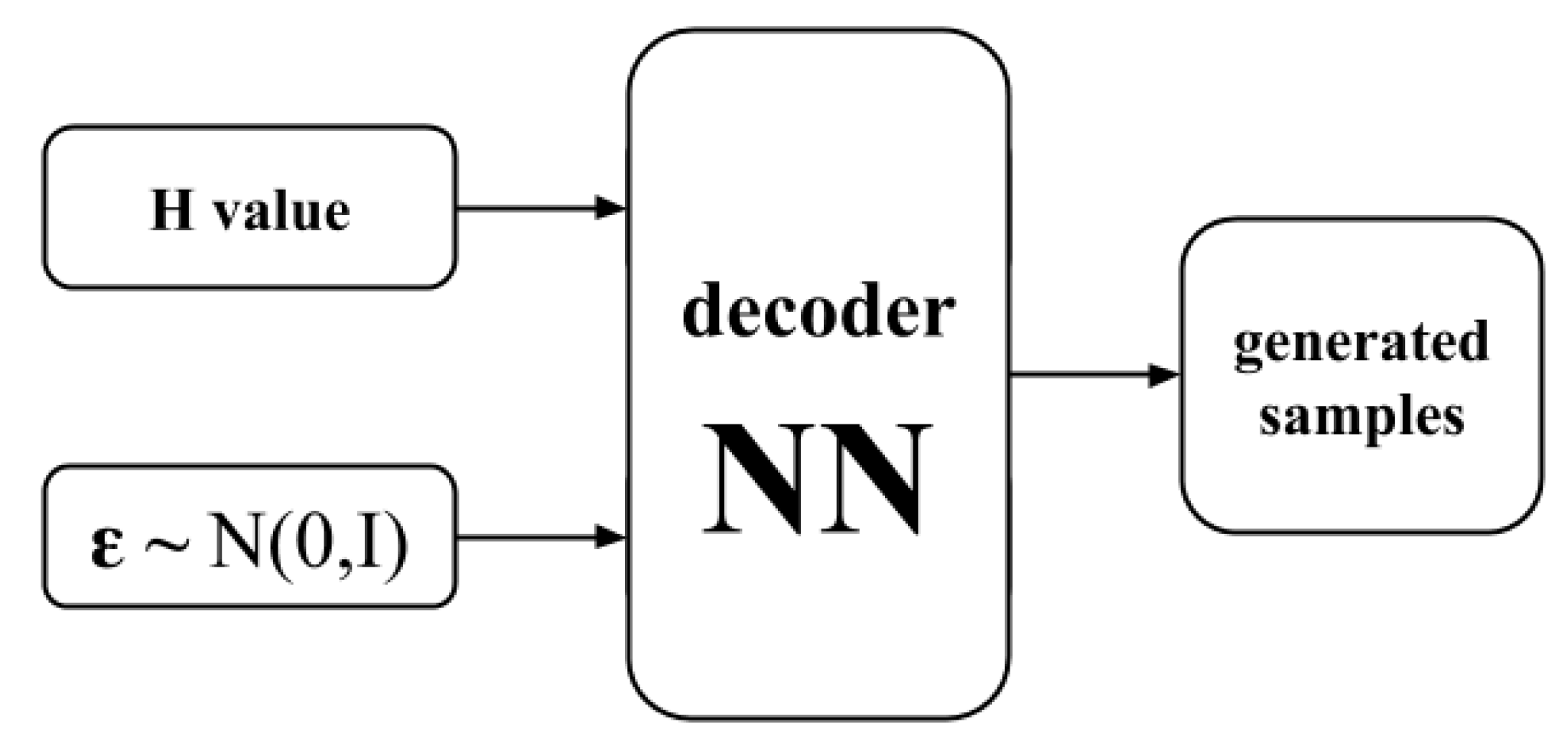

3. Generative Model as a Quantum State

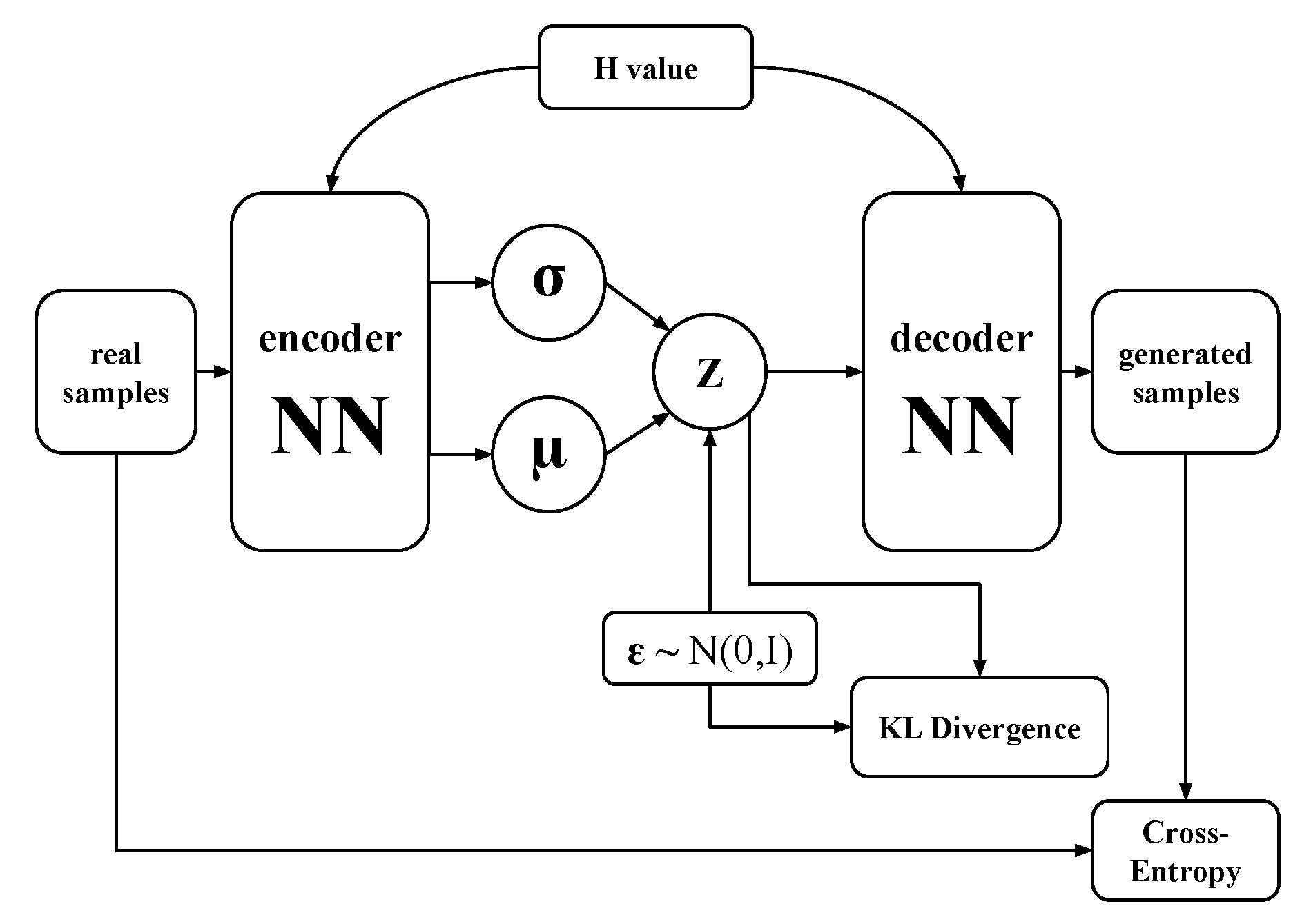

4. Variational Autoencoder Architecture

- We calculate the matrix of log probabilities, taking element-wise logarithm of decoder network output: ,

- We generate a matrix of samples from the standard Gumbel distribution G and sum it up element-wise with the matrix of log probabilities : ,

- Finally, we take the function of the result from the previous step: , where T is a temperature of softmax. The softmax functions is defined by the expression .

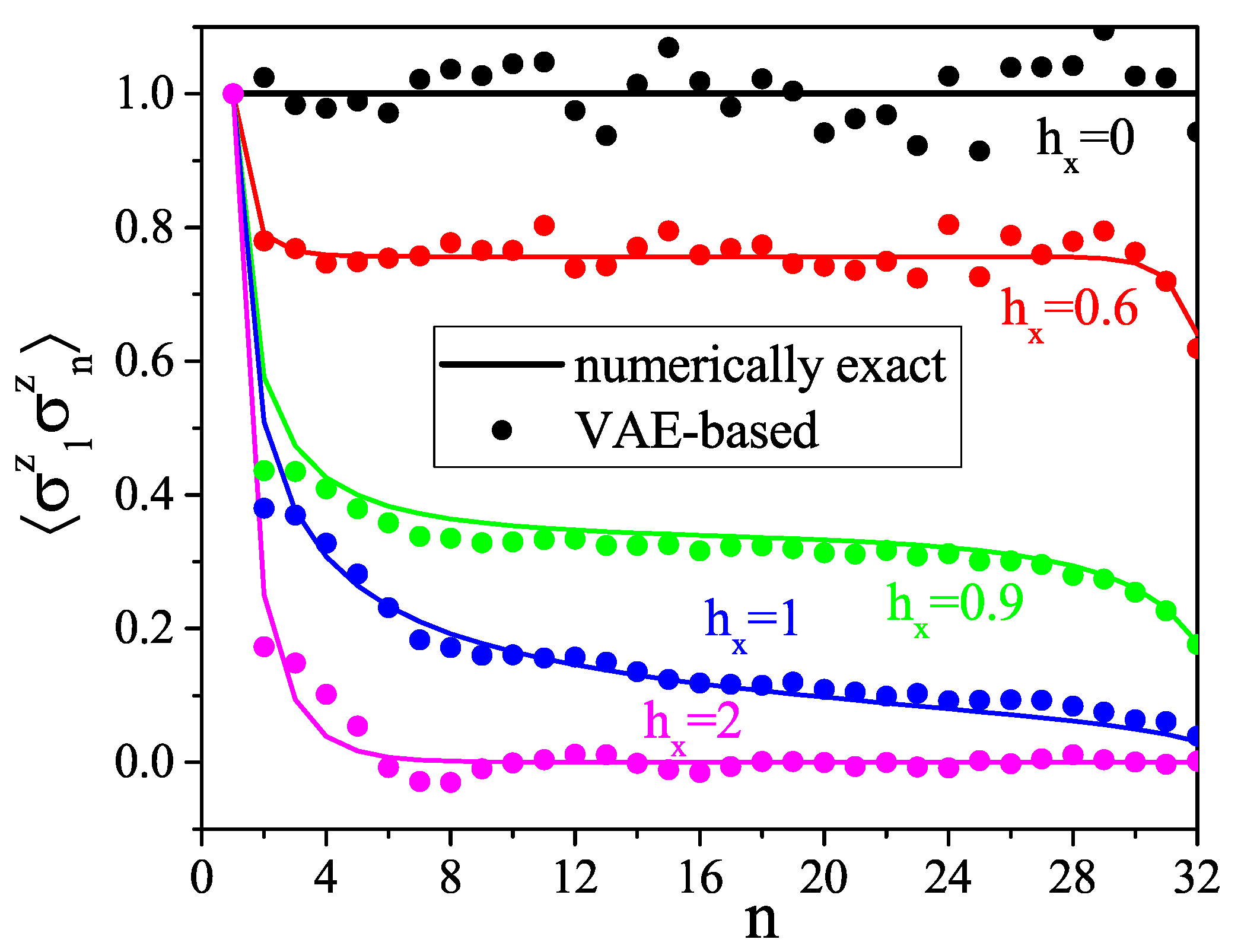

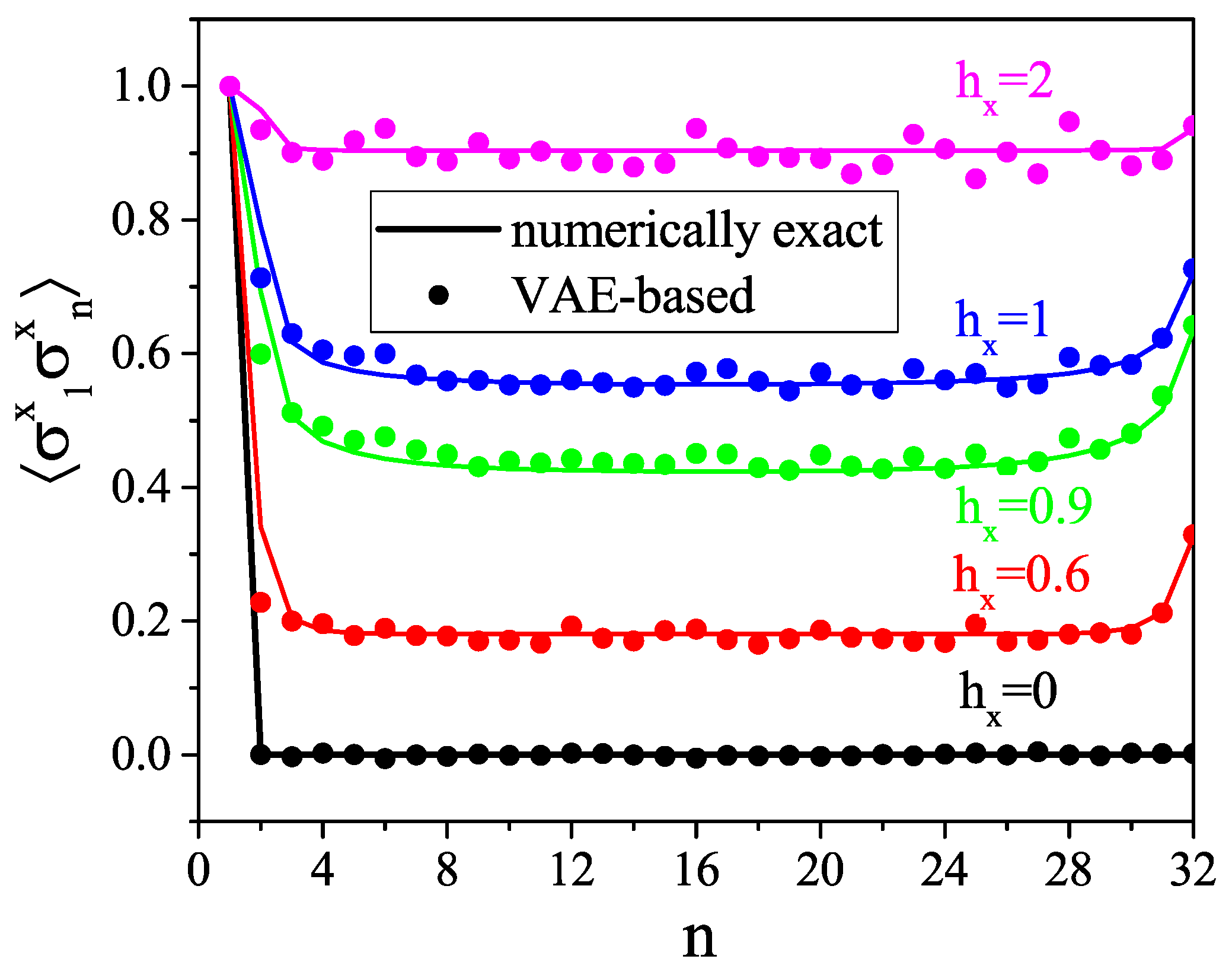

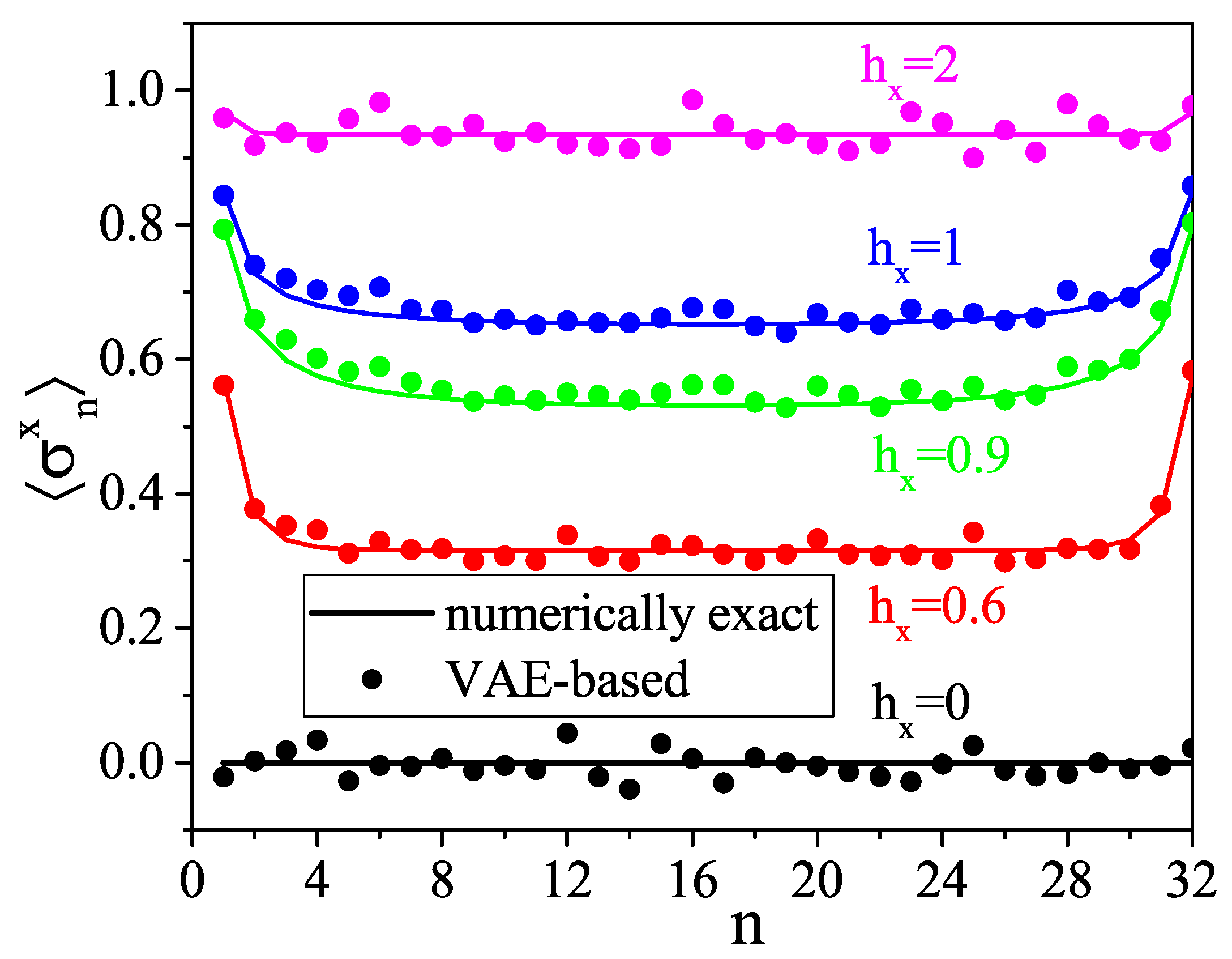

5. Results

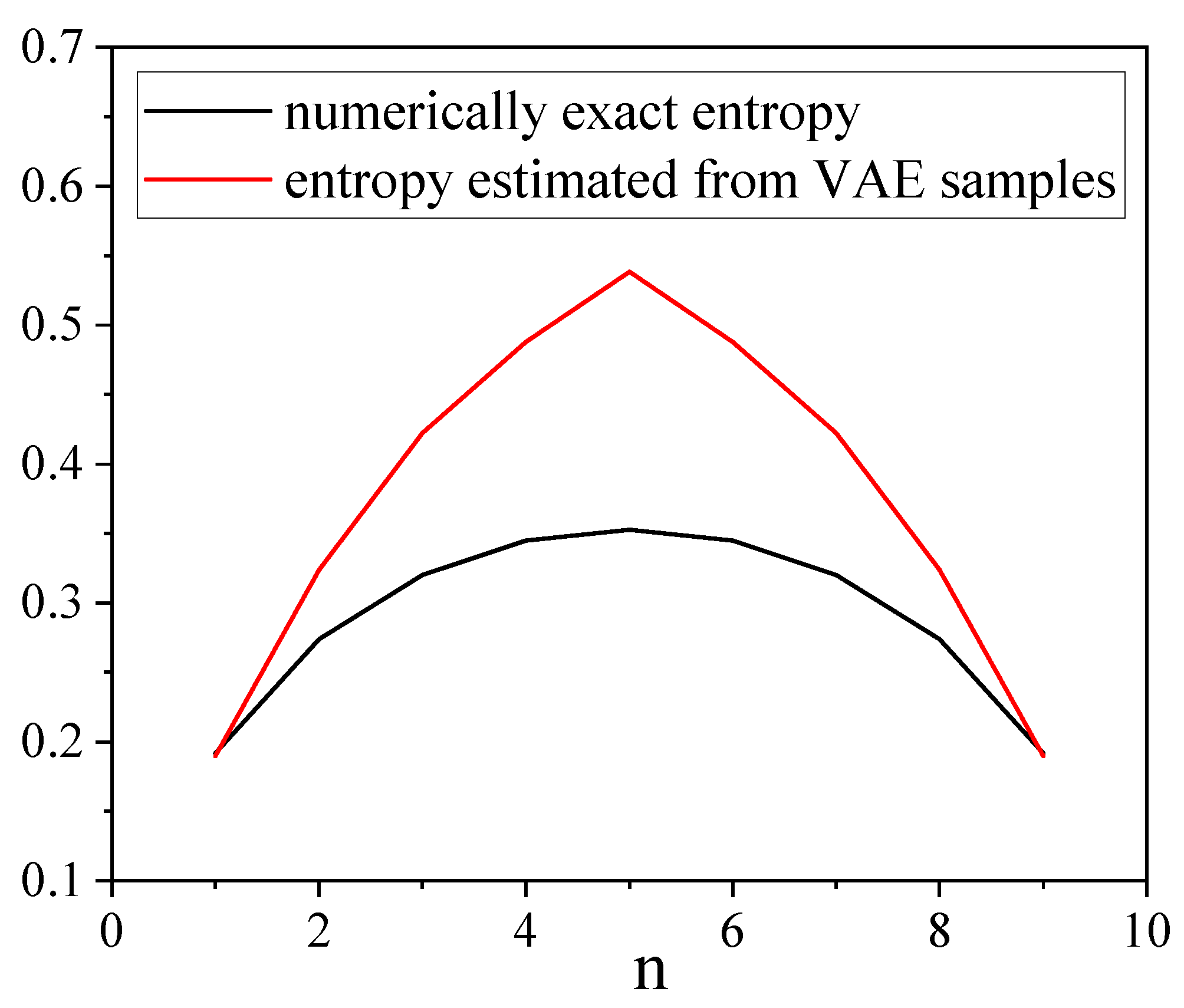

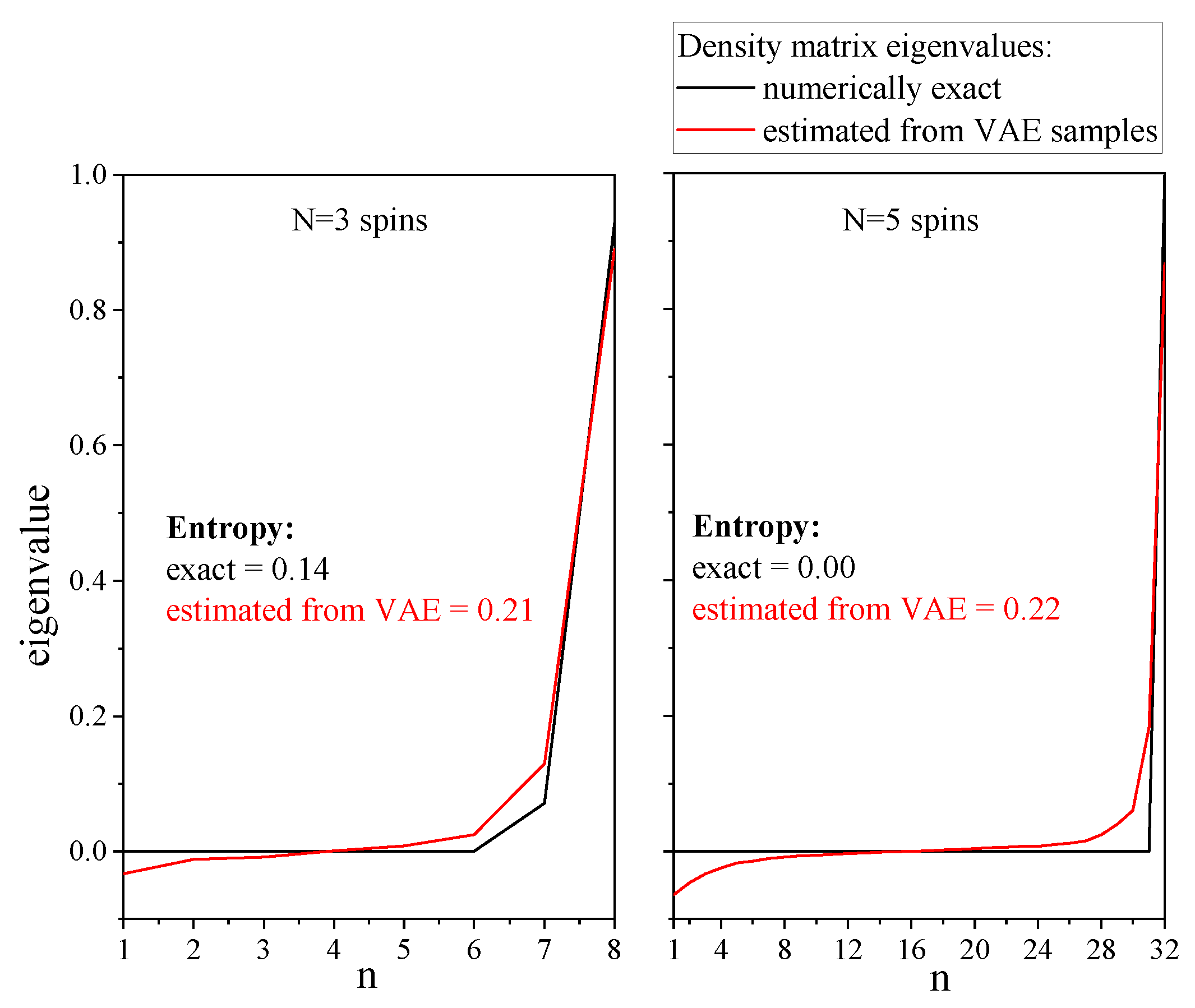

- If one reconstructs a pure state, the VAE smooths the spectrum of the density matrix and approximates the pure state by a slightly mixed state, as illustrated with a simple example in Figure 13.

- The VAE does not account the positivity constraints, which yields negative eigenvalues for the density matrix. These negative eigenvalues even appear in the spectrum of the reduced density matrix, as shown in Figure 13.

6. Conclusions

- For a large system (32 spins), the VAE’s reliability is verified by comparing one- and two-point correlation functions.

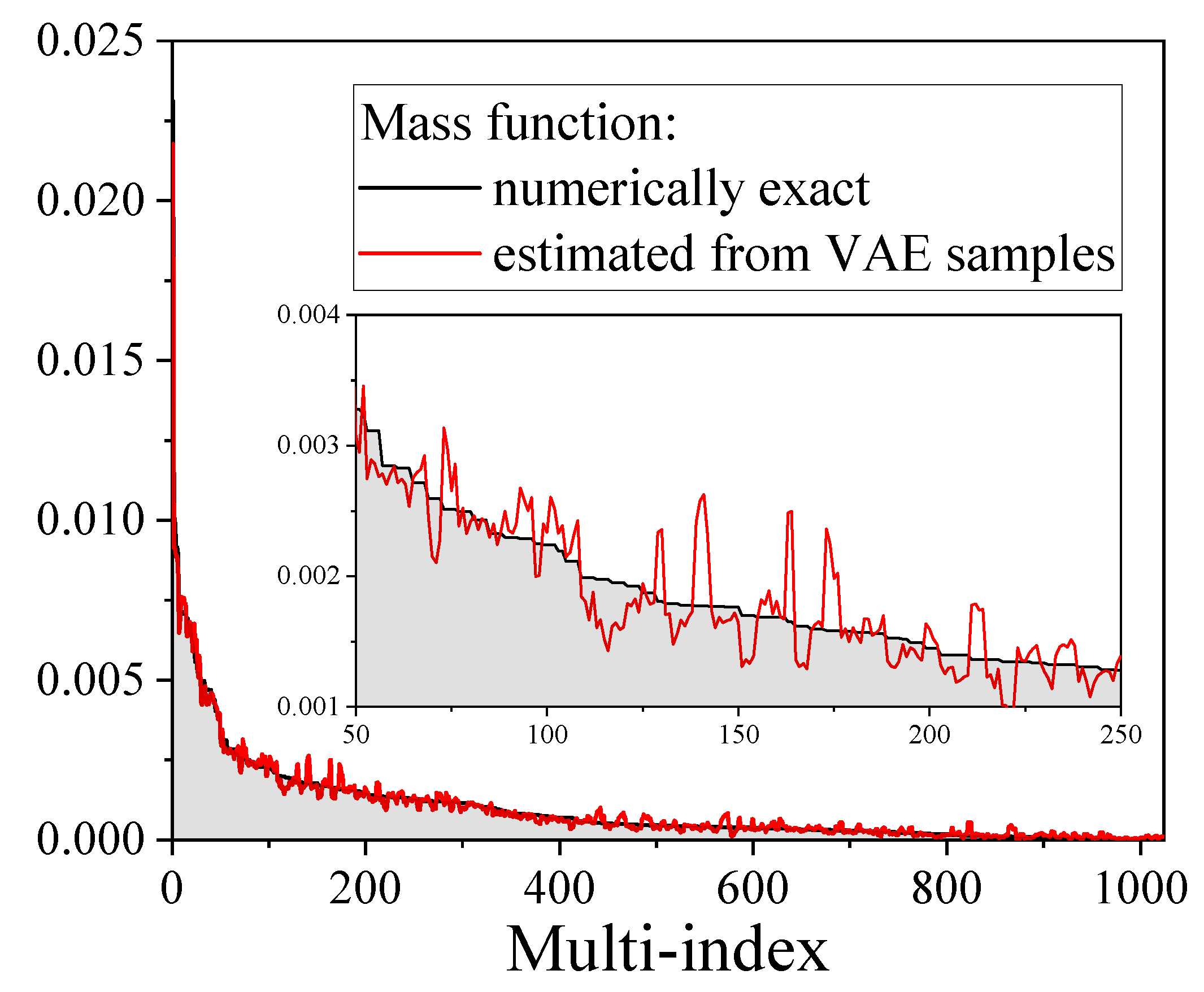

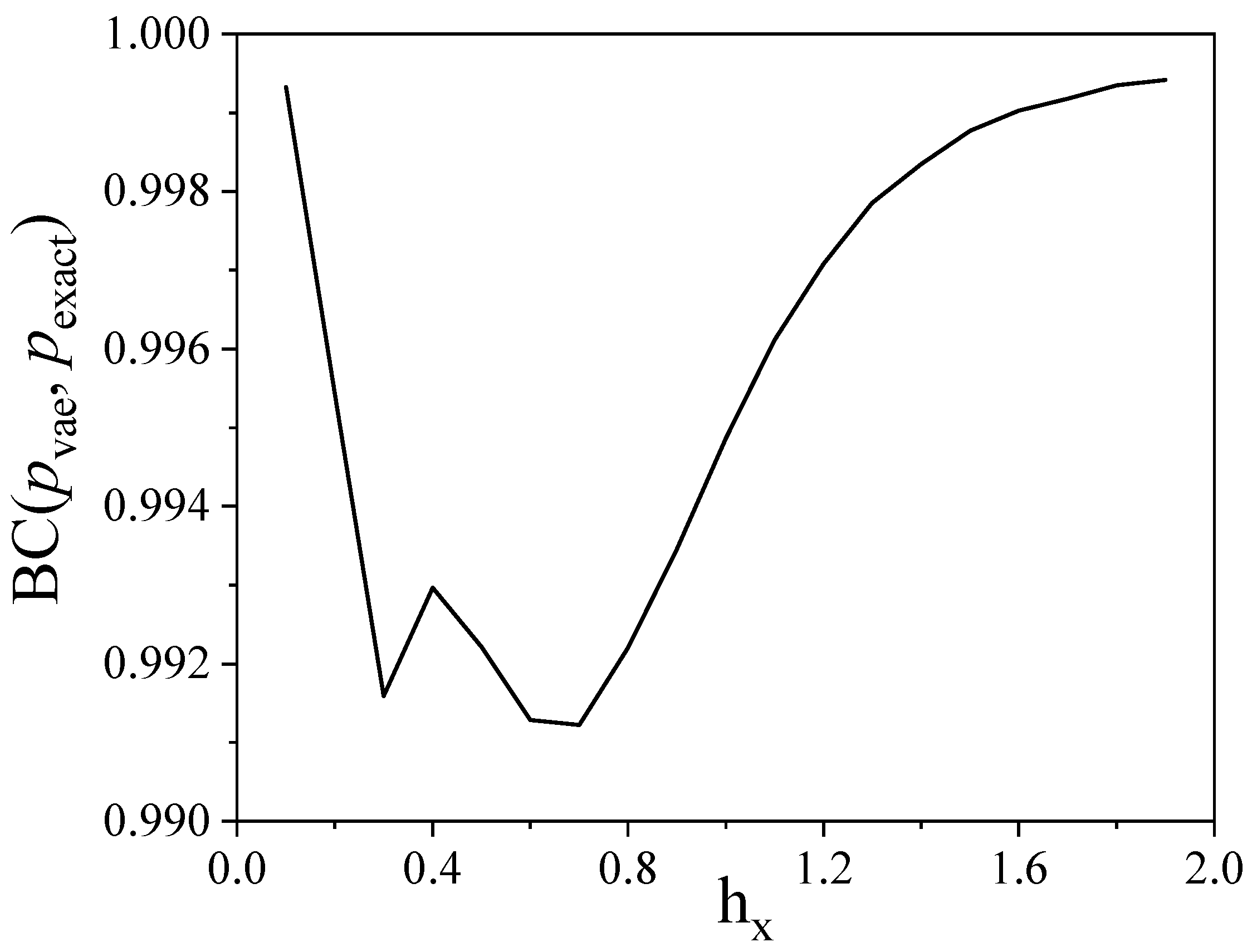

- For small system (five spins), the VAE’s reliability is verified by direct comparison of mass functions.

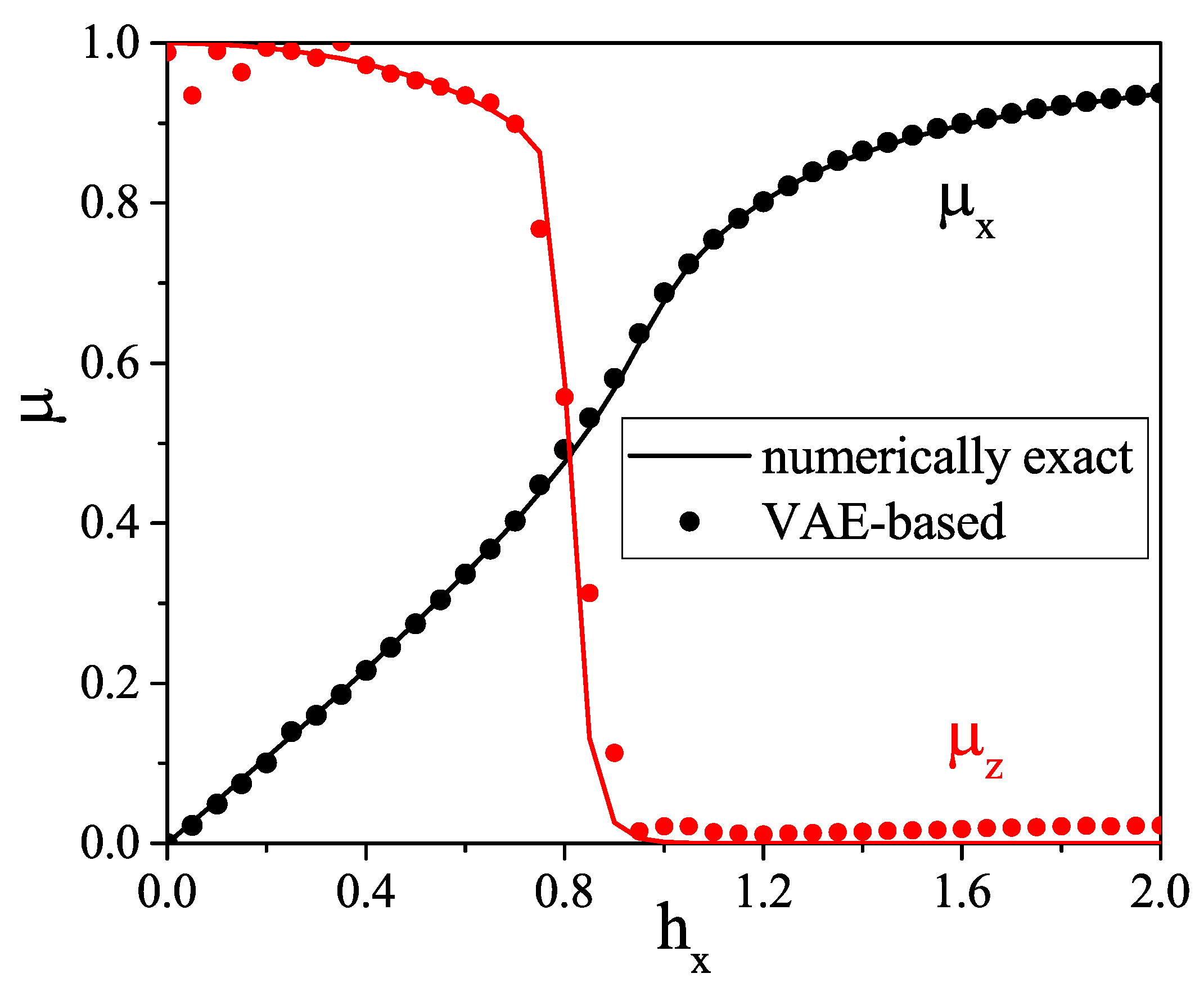

- The VAE can capture a quantum phase transition.

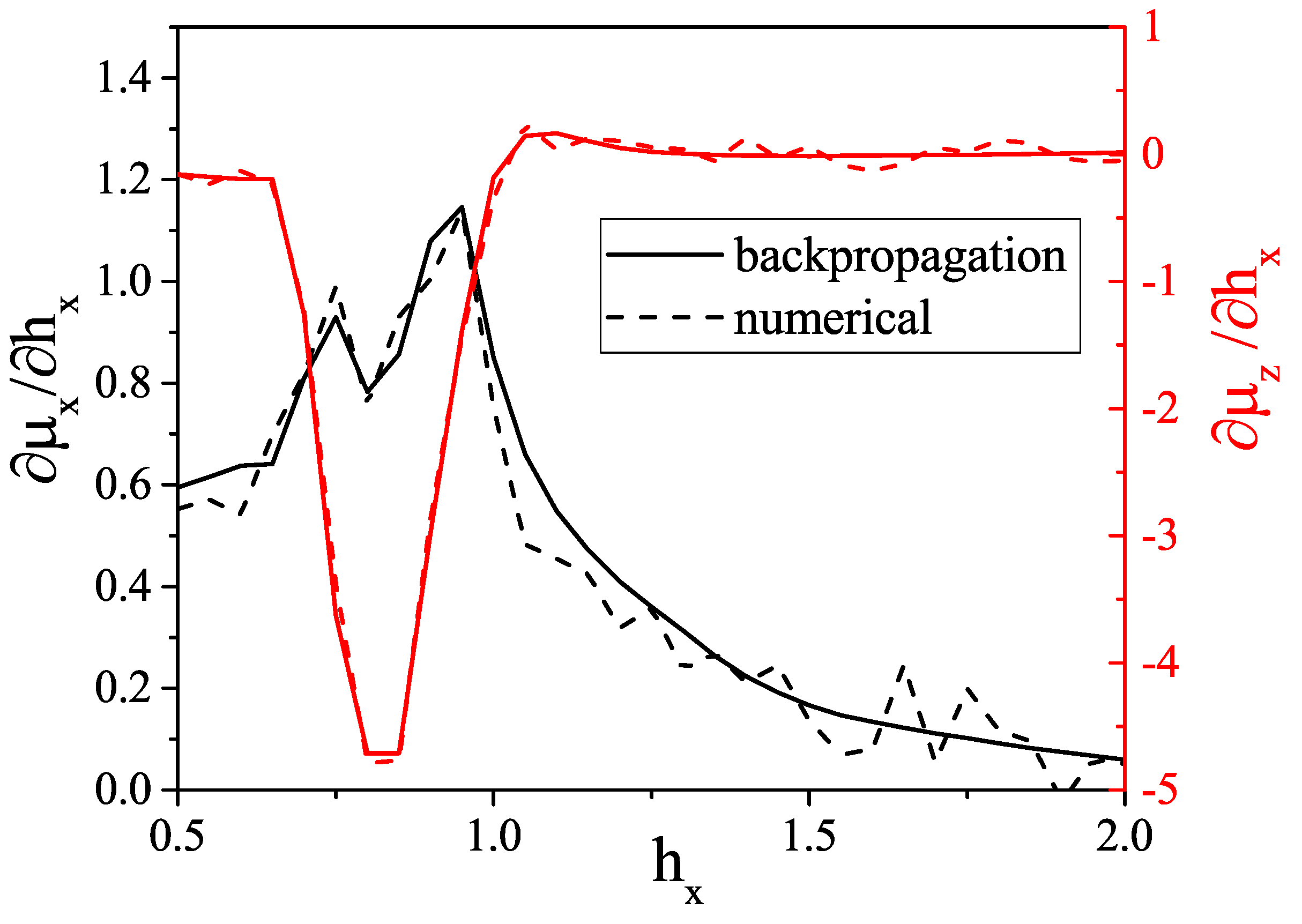

- The response functions (magnetic differential susceptibility tensor) can be obtained using backpropagation through VAE.

- Despite the very good agreement between the VAE-based mass function and the true mass function, the VAE shows limited performance with the determination of the entangled entropy. This is point is the object of further development.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VAE | Variational Autoencoder |

| MPS | Matrix product state |

| TFI | Transverse-field Ising |

| IC | Informationally incomplete |

| POVM | Positive-operator valued measure |

| ELBO | Evidence lower bound |

| NN | Neural network |

| KL | Kullback–Leibler |

| DMRG | Density matrix renormalization group |

Appendix A. VAE: Training and Implementation Details

Appendix B. Sampling from POVM-Induced Mass Function

References

- Muller, I. A History of Thermodynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Onsager, L. Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes. I. Phys. Rev. 1931, 37, 405–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, S.R. Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes; Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bellac, M.; Mortessagne, F.; Batrouni, G.G. Equilibrium and Non-Equilibrium Statistical Thermodynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Apertet, Y.; Ouerdane, H.; Goupil, C.; Lecoeur, P. Revisiting Feynman’s ratchet with thermoelectric transport theory. Phys. Rev. E 2014, 90, 012113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goupil, C.; Ouerdane, H.; Herbert, E.; D’Angelo, Y.; Lecoeur, P. Closed-loop approach to thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 94, 032136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, B. Current trends in finite-time thermodynamics. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 2011, 50, 2690–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouerdane, H.; Apertet, Y.; Goupil, C.; Lecoeur, P. Continuity and boundary conditions in thermodynamics: From Carnot’s efficiency to efficiencies at maximum power. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2015, 224, 839–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apertet, Y.; Ouerdane, H.; Goupil, C.; Lecoeur, P. True nature of the Curzon-Ahlborn efficiency. Phys. Rev. E 2017, 96, 022119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. Uber die beziehung dem zweiten Haubtsatze der mechanischen Warmetheorie und der Wahrscheinlichkeitsrechnung respektive den Satzen uber das Warmegleichgewicht. Wiener Berichte 1877, 76, 373–435. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, J.W. Elementary Principles in Statistical Mechanics; Charles Scribner’s Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, O. Foundations of statistical mechanics. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1979, 42, 1937–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, S.; Lebowitz, J.L.; Zanghì, N. Gibbs and Boltzmann entropy in classical and quantum mechanics. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.11870. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.11870 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Labs Tech. J. 1948, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Neumann, J. Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics. New Edition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, S. Electronic Transport in Mesoscopic Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heikillä, T.T. The Physics of Nanoelectronics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chomaz, P.; Colonna, M.; Randrup, J. Nuclear spinodal fragmentation. Phys. Rep. 2004, 389, 263–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanini, D.; Morosi, G.; Mella, M. Robust wave function optimization procedures in quantum Monte Carlo methods. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 116, 5345–5350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiguin, A.E.; White, S.R. Finite-temperature density matrix renormalization using an enlarged Hilbert space. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 220401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, J.M. Quantum statistical mechanics in a closed system. Phys. Rev. A 1991, 43, 2046–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srednicki, M. Chaos and quantum thermalization. Phys. Rev. E 1994, 50, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigol, M.; Dunjko, V.; Olshanii, M. Thermalization and its mechanism for generic isolated quantum systems. Nature 2008, 452, 854–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymarsky, A.; Lashkari, N.; Liu, H. Subsystem eigenstate thermalization hypothesis. Phys. Rev. E 2018, 97, 012140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dymarsky, A. Mechanism of macroscopic equilibration of isolated quantum systems. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 224302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleo, G.; Becca, F.; Schiró, M.; Fabrizio, M. Localization and glassy dynamics of many-body quantum systems. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Gelin, M.; Zhao, Y. Dynamics of the spin-boson model: A comparison of the multiple Davydov D1, D1.5, D2 Ansätze. Chem. Phys. 2018, 515, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanyon, B.; Maier, C.; Holzäpfel, M.; Baumgratz, T.; Hempel, C.; Jurcevic, P.; Dhand, I.; Buyskikh, A.; Daley, A.; Cramer, M.; et al. Efficient tomography of a quantum many-body system. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.J.; Liu, J.G.; Wang, L.; Xiang, T. Differentiable programming tensor networks. Phys. Rev. X 2019, 9, 031041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetter, A.L.; Walecka, J.D. Quantum Theory of Many-Particle Systems; Dover: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frésard, R.; Kroha, J.; Wölfle, P. The pseudoparticle approach to strongly correlated electron systems. In Strongly Correlated Systems; Avella, A., Mancini, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 171. [Google Scholar]

- Georges, A.; Kotliar, G.; Krauth, W.; Rozenberg, M.J. Dynamical mean-field theory of strongly correlated fermion systems and the limit of infinite dimensions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1996, 68, 13–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negele, J.W.; Orland, H. Quantum Many-Particle Systems; Perseus Books: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Foulkes, W.; Mitas, L.; Needs, R.; Rajagopal, G. Quantum Monte Carlo simulations of solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orús, R. A practical introduction to tensor networks: Matrix product states and projected entangled pair states. Ann. Phys. 2014, 349, 117–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orús, R. Tensor networks for complex quantum systems. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2019, 1, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollwöck, U. The density-matrix renormalization group in the age of matrix product states. Ann. Phys. 2011, 326, 96–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, G. Efficient classical simulation of slightly entangled quantum computations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 147902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenbly, G.; Vidal, G. Quantum criticality with the multiscale entanglement renormalization ansatz. In Strongly Correlated Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 99–130. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, F.A.; Rodríguez-Rosario, C.; Frauenheim, T.; Paternostro, M.; Modi, K. Non-Markovian quantum processes: Complete framework and efficient characterization. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 97, 012127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchnikov, I.; Vintskevich, S.; Ouerdane, H.; Filippov, S. Simulation complexity of open quantum dynamics: Connection with tensor networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 160401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taranto, P.; Pollock, F.A.; Modi, K. Memory strength and recoverability of non-Markovian quantum stochastic processes. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.12583. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.12583 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Milz, S.; Pollock, F.A.; Modi, K. Reconstructing non-Markovian quantum dynamics with limited control. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98, 012108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchnikov, I.A.; Vintskevich, S.V.; Grigoriev, D.A.; Filippov, S.N. Machine learning of Markovian embedding for non-Markovian quantum dynamics. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.07019. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.07019 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Verstraete, F.; Murg, V.; Cirac, J.I. Matrix product states, projected entangled pair states, and variational renormalization group methods for quantum spin systems. Adv. Phys. 2008, 57, 143–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, M.; Nave, C.P. Tensor renormalization group approach to two-dimensional classical lattice models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 120601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenbly, G.; Vidal, G. Tensor network renormalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 180405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemmer, J.; Michel, M. Quantum Thermodynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kosloff, R. Quantum thermodynamics and open-systems modeling. J. Phys. Chem. 2019, 150, 204105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdyan, A.E.; Johal, R.S.; Mahler, G. Work extremum principle: Structure and function of quantum heat engines. Phys. Rev. E 2008, 77, 041118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Johal, R.S. Coupled quantum Otto cycle. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 83, 031135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhlin, Y.; Schön, G.; Shnirman, A. Quantum-state engineering with Josephson-junction devices. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 357–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navez, P.; Sowa, A.; Zagoskin, A. Entangling continuous variables with a qubit array. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 144506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turing, M.A. Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind 1950, 59, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crevier, D. AI: The Tumultuous Search for Artificial Intelligence; BasicBooks: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Biamonte, J.; Wittek, P.; Pancotti, N.; Rebentrost, P.; Wiebe, N.; Lloyd, S. Quantum machine learning. Nature 2017, 549, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carleo, G.; Troyer, M. Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks. Science 2017, 355, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torlai, G.; Mazzola, G.; Carrasquilla, J.; Troyer, M.; Melko, R.; Carleo, G. Neural-network quantum state tomography. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiunov, E.S.; Tiunova, V.V.; Ulanov, A.E.; Lvovsky, A.I.; Fedorov, A.K. Experimental quantum homodyne tomography via machine learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.06589. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.06589 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Choo, K.; Neupert, T.; Carleo, G. Study of the two-dimensional frustrated J1-J2 model with neural network quantum states. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 124125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharir, O.; Levine, Y.; Wies, N.; Carleo, G.; Shashua, A. Deep autoregressive models for the efficient variational simulation of many-body quantum systems. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.04057. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.04057 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Wu, D.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P. Solving statistical mechanics using variational autoregressive networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 080602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharkov, Y.A.; Sotskov, V.E.; Karazeev, A.A.; Kiktenko, E.O.; Fedorov, A.K. Revealing quantum chaos with machine learning. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.09216. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.09216 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Rocchetto, A.; Grant, E.; Strelchuk, S.; Carleo, G.; Severini, S. Learning hard quantum distributions with variational autoencoders. npj Quantum Inf. 2018, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasquilla, J.; Torlai, G.; Melko, R.G.; Aolita, L. Reconstructing quantum states with generative models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Generative Models for Physicists. Lecture note. Available online: http://wangleiphy.github.io/lectures/PILtutorial.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Hewson, A.C. The Kondo Problem to Heavy Fermions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, P. Heavy fermions: Electrons at the edge of magnetism. In Handbook of Magnetism and Advanced Magnetic Materials; Kronmúller, H., Parkin, S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev, S. Quantum Phase Transitions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, P.; Schofield, A. Quantum criticality. Nature 2000, 433, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, P.W. Localized Magnetic States in Metals. Phys. Rev. 1961, 124, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frésard, R.; Ouerdane, H.; Kopp, T. Slave bosons in radial gauge: a bridge between path integral and Hamiltonian language. Nucl. Phys. B 2007, 785, 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Frésard, R.; Ouerdane, H.; Kopp, T. Barnes slave-boson approach to the two-site single-impurity Anderson model with non-local interaction. EPL 2008, 82, 31001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diu, B.; Guthmann, C.; Lederer, D.; Roulet, B. Physique Statistique; Éditions Hermann: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mila, F. Frustrated spin systems. In Many-Body Physics: From Kondo to Hubbard; Pavarini, E., Koch, E., Coleman, P., Eds.; Verlag des Forschungszentrum Jülich: Kreis Düren, Rheinland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Refael, G.; Moore, J.E. Entanglement Entropy of Random Quantum Critical Points in One Dimension. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schollwóck, U. The density-matrix renormalization group. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2005, 77, 259–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ising, E. Beitrag zur Theorie des Ferromagnetismus. Z. Phys. 1925, 31, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramers, H.A.; Wannier, G.H. Statistics of the two-dimensional ferromagnet. Part I. Phys. Rev. 1941, 60, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikov, A.A.; Dmitriev, D.V.; Krivnov, V.Y.; Cheranovskii, V.O. Antiferromagnetic Ising chain in a mixed transverse and longitudinal magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 68, 214406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldea, R.; Tennant, D.A.; Wheeler, E.M.; Wawrzynska, E.; Prabhakaran, D.; Telling, M.; Habicht, K.; Smeibidl, P.; K, K. Quantum criticality in an Ising chain: Experimental evidence for emergent E8 symmetry. Science 2010, 327, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, S.; Keimer, B. Quantum criticality. Phys. Today 2011, 64, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, T. A new approach to quantum statistical mechanics. Prog. Theor. Exp. 1955, 14, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogut, J.B. An introduction to lattice gauge theory and spin systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1979, 51, 659–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the NIPS: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25, Stateline, NV, USA, 3–8 December 2012; pp. 1097–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Holevo, A.S. Probabilistic and Statistical Aspects of Quantum Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Filippov, S.N.; Man’ko, V.I. Inverse spin-s portrait and representation of qudit states by single probability vectors. J. Russ. Laser Res. 2010, 31, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, M.; Fuchs, C.A.; Stacey, B.C.; Zhu, H. Introducing the Qplex: A novel arena for quantum theory. Eur. Phys. J. D 2017, 71, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caves, C.M. Symmetric informationally complete POVMs - UNM Information Physics Group internal report (1999). Available online: http://info.phys.unm.edu/~caves/reports/infopovm.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Myung, I.J. Tutorial on maximum likelihood estimation. J. Math. Psychol. 2003, 47, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, S.N.; Man’ko, V.I. Symmetric informationally complete positive operator valued measure and probability representation of quantum mechanics. J. Russ. Laser Res. 2010, 31, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- mpnum: A Matrix Product Representation Library for Python. Available online: https://mpnum.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Sohn, K.; Lee, H.; Yan, X. Learning structured output representation using deep conditional generative models. In Proceedings of the NIPS: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 3483–3491. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Welling, M. Auto-encoding variational Bayes. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.6114. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1312.6114 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Rezende, D.J.; Mohamed, S.; Wierstra, D. Stochastic backpropagation and approximate inference in deep generative models. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Beijing, China, 21–26 June 2014; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, E.; Gu, S.; Poole, B. Categorical reparameterization with Gumbel-softmax. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.01144. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.01144 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Kusner, M.J.; Hernández-Lobato, J.M. Gans for sequences of discrete elements with the Gumbel-softmax distribution. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.04051. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.04051 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Maddison, C.J.; Mnih, A.; Teh, Y.W. The concrete distribution: A continuous relaxation of discrete random variables. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.00712. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1611.00712 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Metropolis, N.; Rosenbluth, A.W.; Rosenbluth, M.N.; Teller, A.H.; Teller, E. Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines. J. Chem. Phys. 1953, 21, 1087–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chakrabarti, B.K. Colloquium: Quantum annealing and analog quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 1061–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavorsky, A.; Markovich, L.A.; Polyakov, E.A.; Rubtsov, A.N. Highly parallel algorithm for the Ising ground state searching problem. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.05124. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.05124 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Verstraete, F.; Cirac, J.I. Matrix product states represent ground states faithfully. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 094423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisert, J.; Cramer, M.; Plenio, M.B. Colloquium: Area laws for the entanglement entropy. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 277–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.-L.; Li, X.; Das Sarma, S. Quantum entanglement in neural network states. Phys. Rev. X 2017, 7, 021021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, A. On a measure of divergence between two statistical populations defined by their probability distributions. Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc. 1943, 35, 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Boixo, S.; Ronnow, T.F.; Isakov, S.V.; Wang, Z.; Wecker, D.; Lidar, D.A.; Martinis, J.M.; Troyer, M. Evidence for quantum annealing with more than one hundred qubits. Nat. Phys. 2014, 10, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denchev, V.S.; Boixo, S.; Isakov, S.V.; Ding, N.; Babbush, R.; Smelyanskiy, V.; Martinis, J.; Neven, H. What is the computational value of finite-range tunneling? Phys. Rev. X 2016, 6, 031015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navez, P.; Tsironis, G.P.; Zagoskin, A.M. Propagation of fluctuations in the quantum Ising model. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 95, 064304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, A.A.; Artemov, V.G.; Pronin, A.V. A radically new suggestion about the electrodynamics of water: Can the pH index and the Debye relaxation be of a common origin? EPL 2014, 106, 46004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artemov, V.G. A unified mechanism for ice and water electrical conductivity from direct current to terahertz. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 8067–8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Github Repository with Code. Available online: https://github.com/LuchnikovI/Representation-of-quantum-many-body-states-via-VAE (accessed on 7 November 2019).

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.6980 (accessed on 6 November 2019).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luchnikov, I.A.; Ryzhov, A.; Stas, P.-J.; Filippov, S.N.; Ouerdane, H. Variational Autoencoder Reconstruction of Complex Many-Body Physics. Entropy 2019, 21, 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21111091

Luchnikov IA, Ryzhov A, Stas P-J, Filippov SN, Ouerdane H. Variational Autoencoder Reconstruction of Complex Many-Body Physics. Entropy. 2019; 21(11):1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21111091

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuchnikov, Ilia A., Alexander Ryzhov, Pieter-Jan Stas, Sergey N. Filippov, and Henni Ouerdane. 2019. "Variational Autoencoder Reconstruction of Complex Many-Body Physics" Entropy 21, no. 11: 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21111091

APA StyleLuchnikov, I. A., Ryzhov, A., Stas, P.-J., Filippov, S. N., & Ouerdane, H. (2019). Variational Autoencoder Reconstruction of Complex Many-Body Physics. Entropy, 21(11), 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/e21111091