Could Gamification Be a Protective Factor Regarding Early School Leaving? A Life Story

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- O.1: To study the effect of gamification regarding school leaving and adolescence within the life story of Hercules.

- O.2: Establish middle-range theories about the relationship between gamification, school engagement, and adolescent well-being to partially void the gaps existing in literature regarding risk and protective factor related to ESL and adolescent well-being.

2. Background

2.1. The Fight against Early School Leaving in Spain and Policies Aimed at At-Risk Pupils

Policies to Combat Early School Leaving within the Structure of the Spanish Education System. The Curricular Diversification Programme (PDC)

2.2. The Importance of Methodology to Tackle ESL and the Use of Gamification in the Educational Field

Gamification and ESL

2.3. Exploring the Growing Importance of Working on Mental Health and Well-Being in the International Framework and Its Connection with Early School Leaving in the European Context

ESL in the Literature and the Complexity of Linking It to Mental Health and Adolescent Well-Being

3. Materials and Methods

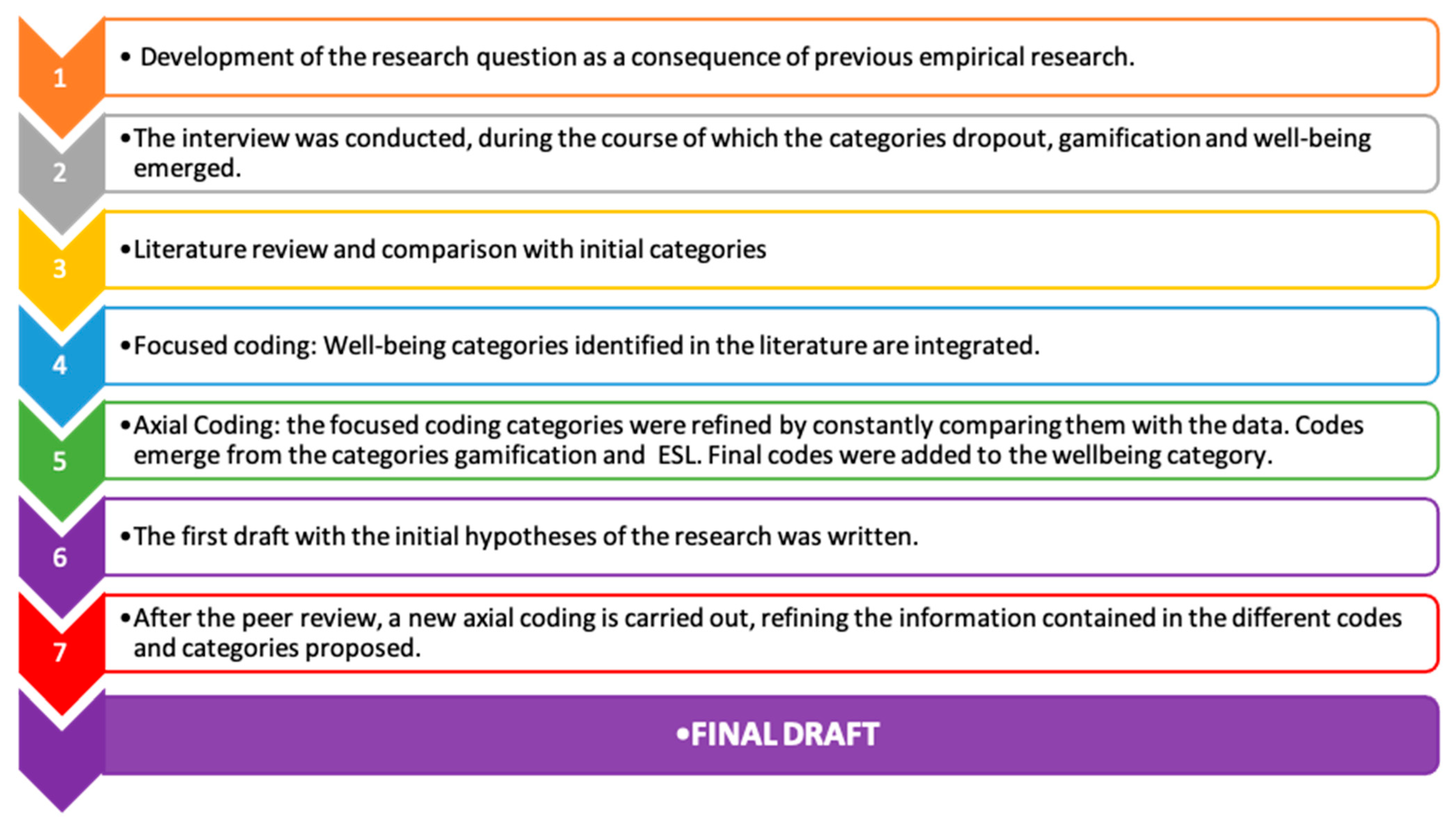

3.1. Study Design and Data Collection

3.2. Sampling Criteria

3.3. Data Analysis and Category Selection Criteria

3.4. Representativeness and Reliability of the Process

4. Results: The Life of Hercules

4.1. Brief Description of Hercules

4.2. Summary of the Dimensions of Hercules’ Life

4.3. The Power of Gamification As a Tool to Tackle Early School Leaving and Improve Adolescent Well-Being

4.3.1. A Scholar Trajectory until Gamification

“I don’t even remember where I started school, and I think I went to all the schools in ***** (the town where the interview was held). I spent a year, I think, in ****** (a nearby town), where I had to go and live with my father, and so as not to lose a year, I signed up for school there. This was the first time meeting my dad, and next year he was gone, I have never seen him again”

“I am very influenceable… Once I even got influenced by a handwriting. I sat down with a friend, and I saw him writing and accidentally copied his handwriting… I am very easily influenced (…) Although, when I went from sixth grade to first secondary grade with all my friends, one of them was the smartest of the whole group, he was a nerd and was studying all the time… everything! But no, I didn’t get influenced by him at all…”

“The second time I did grade six I was approached by a very perfectionist teacher and I said: “Listen, teacher, I’m stupid” […]”. Teachers don’t like people like me, they ignore me, but this is normal” […] “I felt that the last thing I could do was study, that it wasn’t my thing”.

“Once I have a good teacher in la ESO (secondary education) that was very good to me, she told me that I wasn’t a dumb, she was good, but I failed as always”

4.3.2. During the Gamification Process

“I had a kind of class, which was very good, which was like…I don’t know, we were always together, everything was perfect for us and we were 10 students”.

“I was influenced by the teacher, who was very good, I liked him very much… and he was with us all the time, he gave us almost everything… that teacher… I liked him very much”

“I liked the way the teacher did it… he even played games and everything. For example, there was one thing, called gamification, which organized us in groups of two… and then two big groups, one was Egypt and the other Mesopotamia. I even looked for a nickname! I was “Tutankhamun of the first-grade classroom” […]. “I have never liked more going to school”

“And every time we finished an activity the teacher gave us soldiers or food. Then, sometimes you have to fight it, it was like a duel and you had to fight… we arrange everything, it was very cool”.

“This year I didn’t feel like always. I even did homework and everything […] I really liked this game […] I worked at home, I did everything he would send me, I was motivated, I was not even lazy… that was because of my teacher, who I liked. (…) And my classmates flourished the same way, there was one mate who used to fall asleep in every class and that year he approved everything! That was because we all liked the game of Egypt and Mesopotamia”

4.3.3. After Gamification

“In the next year, this was the worst… things changed…, and I… went back to the way I was…I didn’t like it to see me like this again because I was feeling so good, same thing again, that was it… I started to fail, they started to leave me behind. The teacher tried to be good to me… (…) but the next year… that was it… that was it”.

5. Discussion

5.1. Gamification: A Protective Factor against ESL during Its Conductions that Could Negatively Impact Engagement Once Withdrawn

5.2. The Implications on Well-Being

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on a Strategic Framework for European Cooperation in Education and Training (“ET 2020”). Document 17535/08. 2019. Available online: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/educ/107622.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- European Commission. Tackling Early School Leaving: A key Contribution to the Europe 2020 Agenda. COM 2011, 18 Final. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/education/school-edu-cation/doc/earlycom_es.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Guerrero, L. El abandono escolar prematuro en España, un reto para el sistema educativo español. In Proceedings of the XIV Congreso Internacional de Teoría de la Educación 2017, Murcia, Spain, 21–23 November 2017; pp. 987–995, ISBN 978-84-697-7896-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabini, A.; Rambla, X. ¿De nuevo con el abandono escolar? Un análisis de políticas, prácticas y subjetividades. Profr. Rev. Currículum Form. Profr. 2015, 19, 1–7. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=56743410001 (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Escudero, J.M.; González, M.T.; Martínez, B. El fracaso escolar como exclusión educativa: Comprensión, políticas y prácticas. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2009, 50, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enguita, F.M. Del desapego al desenganche y de éste al fracaso escolar. Propues. Educ. 2011, 35, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tarabini, A.; Jacovkis, J.; Montes, A. Factors in educational exclusion: Including the voice of the youth. J. Youth Stud. 2017, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Houtte, M. So Where’s the Teacher in School Effects Research?: The Impact of Teacher’s Beliefs, Culture, and Behavior on Equity and Excellence in Education. In Equity and Excellence in Education: Towards Maximal Learning Opportunities for All Students; Van Den Branden, K., Van Avermaet, P., Van Houtte, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Castel, R. La Metamorfosis de la Cuestión Social; Paidós: Madrid, Spain, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Amores Fernández, F.J.; Luengo Navas, J.; Ritacco, R.M. Educar en contextos de exclusión social: Necesidades y cambios desde la perspectiva del profesorado. Un estudio de casos en la provincia de Granada. Rev. Fuentes 2012, 12, 187–206. Available online: https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/32984/Educar%20en%20contextos%20de%20exclusion%20social.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Reay, D.; Gill, C.; David, J. White Middle-Class Identities and Urban Schooling; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2001; Available online: https://www.palgrave.com/gp/book/9780230224018 (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Rampazzo, L.; Davis, R.J.; Carbone, S.; Mocanu, A.; Campion, J.; Carta, M.G.; Daníelsdóttir, S.; Holte, A.; Huurre, T.; Matloňová, Z.; et al. Situation Analysis and Recommendations for Action. 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/mental_health/docs/2017_mh_schools_en.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- European Commission Mental Health: Challenges and Possibilities, Conference Proceedings. 2013. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/mental_health/docs/lt_presidency_vilnius_conclusions_20131010_en.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Zichermann, G.; Cunningham, C. Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Werbach, K.; Hunter, D. For the Win: How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business; Wharton Digital Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, R.; García, A. Bibliotecas, juegos y gamificación: Una tendencia de presente con mucho futuro. Anu. ThinkEPI 2018, 12, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corchuelo, C.A. Gamificación en educación superior: Experiencia innovadora para motivar estudiantes y dinamizar contenidos en el aula. Edutec. Rev. Electrón. Tecnol. Educ. 2018, 63, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, I.M.; Ruiz, M. Análisis sobre nuevas metodologías activas basadas en el ABP y en la Gamificación en los estudios de Máster del Profesorado en Educación Secundaria. In Proceedings of the XV Jornadas de Redes de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria—REDES Libro de Actas, Alicante, Spain, 1–2 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pintor, P. Gamificando con Kahoot! En evaluación formativa. Infanc. Educ. Aprendiz. IEYA 2017, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Prieto, E.; Alcaraz, V.; Sánchez, A.J.; Grimaldi, M. Aprendizajes Significativos mediante la Gamificación a partir del Juego de Rol: “Las Aldeas de la Historia”. Espiral. Cuad. Profr. 2018, 11, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Gavira, J.; García-Fernández, J.; Sánchez-Oliver, A.J.; Grimaldi-Puyana, M. Gamificación,Emprendimiento y Deporte mediante las Aplicaciones Móviles. In INNOVAGOGÍA 2016. III. Congreso Internacional sobre Innovación Pedagógica y Praxis Educativa. Procedings; López-Meneses, E., Cobos Sanchiz, D., Martín Padilla, A., Molina-García, Jaén Martínez, A., Eds.; AFOE Formación: Sevilla, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, J. Gamificando el Huerto Escolar en Educación Primaria. Los Super Héroes al Rescate. In Proceedings of the III Congreso Internacional de Educación Mediática y Competencia Digital; 2017. Available online: http://ocs.editorial.upv.es/index.php/HEAD/HEAd20/paper/viewFile/10960/5527 (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Manzano, A.P.; Baeza, J.A. Gamificación transmedia para la divulgación científica y el fomento de vocaciones procientíficas en adolescentes. Comun. Rev. Cient. Iberoam. Comun. Educ. 2018, 55, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Peirats Chacón, J.; Marín Suelves, D.; Vidal Esteve, M.I. Bibliometría Aplicada a la Gamificación Como Estrategia Digital de Aprendizaje; 2019; Available online: https://revistas.um.es/red/article/view/386921 (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Tsalapatas, H.; Heidmann, O.; Alimisi, R.; Koutsaftikis, D.; Tsalapatas, S.; Houstis, E. A Gamified Community for Fostering Learning Engagement Towards Preventing Early School Leaving. In International Conference on Serious Games, Interaction, and Simulation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 86–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, M.; Saridaki, M.; Kolovou, E.; Mourlas, C.; Brown, D.; Burton, A.; Yarnall, T. Designing Location-Based Gaming Applications with Teenagers to Address Early School Leaving; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2015; Available online: https://search.proquest.com/conference-papers-proceedings/designing-location-based-gaming-applications-with/docview/1728409717/se-2?accountid=14542 (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Tarabini, A.; Fontevlia, C.; Curran, M.; Montes, A.; Parcerisa, L.; Rambla, X. ¿Continuidad o Abandono Escolar? El Efecto de la Escuela en las Decisiones de los Jóvenes; Centro Reina Sofia: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Network of Experts in Social Sciences of Education and Training (NESSE). Early School Leaving. Lessons from Research for Policy Makers; INRP: Paris, France, 2009; Available online: http://www.nesse.fr (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). Base de Datos; Gobierno de España: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Psacharopoulos, G. The Costs of School Failure: A Feasibility Study; EENEE: Brussels, Begium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Luzón, A.; Torres, M. Las Políticas Educativas Contra el Abandono Escolar Temprano en Andalucia: La Beca 6000; Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero Muñoz, J.M.; Martínez Domínguez, B. Policies for Combating School Failure: Special Programmes or Sea Changes in the System and in Education? Ministerio de Educación: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Medina, F. Programas de Diversificación Curricular: Una Medida de Atención a la Diversidad; Revista Digital: Innovación y Experiencias Educativas: Spain, 2009; Volume 16, Available online: https://archivos.csif.es/archivos/andalucia/ensenanza/revistas/csicsif/revista/pdf/Numero_16/FRANCISCA_MARTINEZ_2.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Tedesco, J.C. Modelo pedagógico y fracaso escolar. In Revista de la CEPAL; UN, 1983; Available online: http://otrasvoceseneducacion.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Modelo-Pedago%CC%81gico-y-Fracaso-Escolar-Juan-Carlos-Tedesco.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Wehlage, G.G.; Rutter, R.A.; Smith, G.A.; Lesko, N.; Fernandez, R.R. Reducing the Risk: Schools as Communities of Support; Falmer Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero, J.M. Fracaso Escolar, exclusión educativa: ¿de qué se excluye y cómo? Profr. Rev. Curric. Form. Profr. 2005, 1, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmpourtzis, G. Educational Game Design Fundamentals: A Journey to Creating Intrinsically Motivating Learning Experiences; AK Peters/CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, C.; Featherstone, G.; Aston, H.; Houghton, E. Game-Based Learning: Latest Evidence and Future Directions; NFER: Slough, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hamari, J.; Shernoff, D.J.; Rowe, E.; Coller, B.; Asbell-Clarke, J.; Edwards, T. Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game-based learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 54, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, A.R.; Mayben, R.; Boman, T. Integrating game-based learning initiative: Increasing the usage of game-based learning within K-12 classrooms through professional learning groups. TechTrends 2016, 60, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, N. Encouraging engagement in game-based learning. Int. J. Game Based Learn. IJGBL 2011, 1, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ara, S. Use of songs, rhymes and games in teaching English to young learners in Bangladesh. Dhaka Univ. J. Linguist. 2009, 2, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.J.F.; Pruitt, K.W. Homework assignments: Classroom games or teaching tools? Clear. House 1979, 53, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvaro-Tordesillas, A.; Alonso-Rodríguez, M.; Poza-Casado, I.; Galván-Desvaux, N. Gamification experience in the subject of descriptive geometry for architecture. Educ. XX1 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining “gamification”. In Proceedings of the 15th international academic MindTrek conference: Envisioning future media environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barata, G.; Gama, S.; Jorge, J.A.; Gonçalves, D.J. Relating gaming habits with student performance in a gamified learning experience. In Proceedings of the First ACM SIGCHI Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Toronto, ON, Canada, 19–22 October 2014; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Araya, R.; Arias Ortiz, E.; Bottan, N.L.; Cristia, J.P. Does Gamification in Education Work?: Experimental Evidence from Chile. IDB. Working Paper. 2019. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Does-Gamification-in-Education-Work-%3A-Experimental-Araya-Ortiz/ad817d9f526584f3cef76d0629dbe326e2df2421 (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Domínguez, A.; Saenz-De-Navarrete, J.; De-Marcos, L.; Fernández-Sanz, L.; Pagés, C.; Martínez-Herráiz, J. Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Comput. Educ. 2013, 63, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groening, C.; Binnewies, C. “Achievement unlocked!”-the impact of digital achievements as a gamification element on motivation and performance. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maican, C.; Lixandroiu, R.; Constantin, C. Interactivia. ro–A study of a gamification framework using zero-cost tools. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Andreu, J.M. Una revisión sistemática sobre gamificación, motivación y aprendizaje en universitarios. Teor. Educ. Rev. Interuniv. 2020, 32, 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alsawaier, R.S. The effect of gamification on motivation and engagement. Int. J. Inf. Learn. Technol. 2018, 35, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, M. Gamification: The effect on student motivation and performance at the post-secondary level. Issues Trends Educ. Technol. 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M. Técnicas de gamificación aplicadas en la docencia de Ingeniería Informática. ReVisión 2015, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho, P.; Vega, J.; Guerreo, M.A.; Guerrero, L.; Alías, A. Estrategias de Enseñanza Innovadoras para Nuevos Escenarios de Aprendizaje; Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 115–125. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv105bcrt (accessed on 26 February 2020). [CrossRef]

- Van der Kooij, K.; van Dijsseldonk, R.; van Veen, M.; Steenbrink, F.; de Weerd, C.; Overvliet, K.E. Gamification as a sustainable source of enjoyment during balance and gait exercises. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markopoulos, A.P.; Fragkou, A.; Kasidiaris, P.D.; Davim, J.P. Gamification in engineering education and professional training. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2015, 43, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calonge, L. Cómo gamificar una práctica de laboratorio para estudiantes de magisterio. In Proceedings of the XX simposio Sobre Enseñanza de la Geología, Menorca, Spain, 9–14 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogiannakis, M.; Papadakis, S.; Zourmpakis, A.-I. Gamification in Science Education. A Systematic Review of the Literature. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzano-León, A.; Camacho-Lazarraga, P.; Guerrero-Puerta, M.A.; Guerrero-Puerta, L.; Alías, A.; Trigueros, R.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M. Adaptation and Validation of the Scale of Types of Users in Gamification with the Spanish Adolescent Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.A.; Dyson, J.; Cowdell, F.; Watson, R. Do universal school-based mental health promotion programmes improve the mental health and emotional wellbeing of young people? A literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e412–e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wexler, P. Becoming Somebody: Towards a Social Psychology of the School; Falmer Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, J.; Hattam, R. ‘Dropping Out’, Drifting Off, Being Excluded: Becoming Somebody without School; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mchugh, K. No Second chances: Want to meet the needs of early school-leavers? Focus on their mental health). Adult Learner: Ir. J. Adult Community Educ. 2015, 61–74. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1077725.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Govorova, E.; Benítez, I.; Muñiz, J. Predicting Student Well-Being: Network Analysis Based on PISA 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgonovi, F.J.P. A Framework for the Analysis of Student Well-Being in the Pisa 2015 Study: Being 15 In 2015; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Mental Health: Challenges and Possibilities; ECHI: Vilnus, Lithuania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, P. The Neglected Shadow: European perspectives on emotional supports for early school leaving prevention. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2011, 3, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Novóa, A. The Blindness of Europe: New Fabrications in the European Educational Space. J. Educ. 2013, 1, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiente, O.; Capsada-Munsech, Q.; de Otero, J.P.G. Educationalisation of youth unemployment through lifelong learning policies in Europe. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Limerick Health Promotion Service. “Nihil Nisi Labore’-’Nothing Achieved Without Effort” Health Impact Assessment of Early School Leaving, Absenteeism and Truancy. 2008. Available online: http://www.limerickregeneration.org/hia-early-school-leavers.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2020).

- Higgins, C.; Lavin, T.; Metcalfe, O. Health Impacts of Education—A Review; Institute of Public Health in Ireland: Dublin, Ireland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger, R.W. Dropping Out: Why Students Drop Out of High School and What Can Be Done about It; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, A. La LOE ante el fracaso, la repetición y el abandono escolar. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2007, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Liem, J.H.; Dillon, C.O.; Gore, S. Mental Health Consequences Associated with Dropping Out of High School. In Proceedings of the 109th Annual Conference of The American Psychological Association, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–28 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet, C.; Hernández-Montoya, D.; Borges, G.; Méndez, E.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. Youth who neither study nor work: Mental health, education and employment. Salud Publica Mex. 2012, 54, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Benjet, C.; Borges, G.; Medina-Mora, M.E.; Zambrano, J.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. Youth mental health in a populous city of the developing world: Results from the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2009, 50, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, S.S.; Walsh, A.K.; Goldston, D.B.; Arnold, E.M.; Reboussin, B.A.; Wood, F.B. Suicidality, school dropout, and reading problems among adolescents. J. Learn. Disabil. 2006, 39, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.; Kelly, E.; Watson, D. School Leavers Survey Report; ESRI and Department of Education and Science: Dublin, Ireland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot, M.G.; Wilkinson, R.G. Social Determinants of Health, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie, J.; Shipley, M.; Stansfeld, S.; Marmot, M. Effects of chronic job insecurity on self-reported health, minor psychiatric morbidity, physiological measures, and health related behaviours in British civil servants: The Whitehall II study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balanda, K.; Wilde, J. Inequalities in Mortality 1989–1998: A Report on All-Ireland Mortality Data; Institute of Public Health: Dublin, Ireland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, B.S. Non-school correlates of dropout: An integrative review of the literature. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 1998, 20, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. Handb. Qual. Res. 2000, 2, 509–535. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructionism and the grounded theory method. Handb. Constr. Res. 2008, 1, 397–412. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K.; Keller, R. A personal journey with grounded theory methodology. Kathy Charmaz in conversation with Reiner Keller. In Forum: Qualitative Social Research; 2016; Volume 17, Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2541 (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Charmaz, K.; Belgrave, L. Grounded theory. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; 2007; Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007%2F978-981-10-2779-6_84-1 (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Charmaz, K.; Belgrave, L. Qualitative interviewing and grounded theory analysis. SAGE Handb. Interview Res. Complex. Craft 2012, 2, 347–365. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarotti, F. Storia e Storie di Vita; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Case studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1994; pp. 236–247. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Validity and generalization in future case study evaluations. Evaluation 2013, 19, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, B. The Advantages and Limitations of Single Case Study Analysis; E-International Relations, 2014; Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Advantages-and-Limitations-of-Single-Case-Study-Willis-Elman/b9cccbe8ec7f9a82d4e289ca5e10be2a1ef0433d (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Anderson, P.A. Decision making by objection and the cuban missile crisis. Adm. Sci. Q. 1983, 28, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinfield, L.T. A field evaluation of perspectives on organizational decision making. Adm. Sci. Q. 1986, 31, 365–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin, A.E. Single-Case Research Designs, Second Edition. Child Fam. Behav. Ther. 2012, 34, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 100. Tate, R.; Perdices, M.; Rosenkoetter, U.; Mcdonald, S.; Togher, L.; Shadish, W.; Horner, R.; Kratochwill, T.; Barlow, D.; Kazdin, A.; et al. The Single-Case Reporting Guideline In BEhavioural Interventions (SCRIBE). Explanation and elaboration. Arch. Sci. Psychol. 2016, 4, 10–31. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, D.M.; Wolf, M.M.; Risley, T.R. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1968, 1, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.P.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L.D. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int. J. Wellbeing 2012, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waterman, A.S. Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, J.; Abdallah, S.; Steuer, N.; Thompson, S.; Marks, N. National Accounts of Well-Being: Bringing Real Wealth onto the Balance Sheet; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, Y.; Shang, L. An RQDA-based constructivist methodology for qualitative research. Qual. Mark. Res. An Int. J. 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory Strategies for Qualitative Research; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Mahali, A.; Lynch, I.; Fadiji, A.W.; Tolla, T.; Khumalo, S.; Naicker, S. Networks of well-being in the global south: A critical review of current scholarship. J. Dev. Soc. 2018, 34, 373–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cognitive Dimension | Hercules’ perception of his cognitive abilities is closely linked to the school environment, and school results. He consequently associates his failure at school with low IQ and poor general skills. Describing himself as "dumb and lazy". |

| Psychological dimension | This perception of his cognitive abilities affect him negatively, and causes his school expectations to be very low, anticipating failure even when the school year has not begun. These low expectations cause him to see himself as a stranger to the school environment, so much so that when asked directly about his school expectations he says: “I felt that the last thing I could do was study, that it wasn’t my thing”. Even so, he acknowledges that there are two moments in his school career when he felt motivated in the school environment. These are in the training course he is currently attending, and during a school year when a gamification experience was carried out in the classroom. However, his motivation, as he points out, comes from different circumstances, such as being able to find a better job in the first case, and methodological reasons in the second (both cases will be seen in more detail in the following sections). In general, when talking about his overall life satisfaction, he describes himself as happy, although he recognizes that there are very difficult moments in his daily life, motivated by economic tensions, the feeling of job uncertainty, family problems, and lack of fulfilment. |

| Physical dimension | With regard to the physical dimension, Hercules claims to have more or less healthy habits, and highlights his position against drug consumption, both before and after dropping out of school. |

| Social dimension | He constantly highlights the influence that the class group had on his school results, which was a major factor in leaving school, but makes it clear that he can only be influenced by “bad” things. This influence is identified as one of the factors that led to his desertion, as he was assigned to a class in which all the students were year-round students. The relationship with his teachers is also important to him: " that it is what I like, that they are good, that they treat you well and speak to you… and they are worried… I don’t know…" In general, Hercules perceives that teachers have ignored his needs, although when asked why, he tends to take responsibility, explaining that for teachers to listen, you have to “study and do your homework” and he did none of these things. However, on the occasions when he has perceived success in the school environment, he attributes this success to external circumstances, in this case to the attitude and methodology of the teachers. As far as his relationship with his relatives is concerned, it should be noted that his mother has addiction issues, and his father, with the exception of one year in which he lived with him, has been totally absent. The relationship with the parents has therefore been unstable, and they have been little involved in the educational process. From the third secondary grade onwards, his uncles took custody of him, and both are very concerned for Hercules education. |

| Material dimension | From a material point of view, Hercules’ life has been highly conditioned by his many changes of residence, which have been accompanied by changes of school. This is identified by the interviewee as a chaotic aspect, so much so that he is not even able to remember how many schools he has been to. These changes of residence and school have been accompanied by changes in legal custody, so it could be said that the material resources at their disposal have been unstable during their school years. It is significant that, although in all the schools and high schools where he has been, there were school counsellors as part of the resources of the center, who could have worked on some of Hercules’ needs. He stresses that their role with respect to the students was absent, and that they never worked on their study techniques, their learning needs, their psychological needs, their self-esteem, or their self-concept. After leaving school, the low economic resources of his current family unit, made up of his older brother, his uncles, and his cousins, have forced Hercules to work in non-legislated activities, such as street vending on the beach. This was a source of discomfort for him, as he felt exploited and did not allow him to shape a future life plan. In addition, the lack of means to acquire a vehicle forced him to walk about 20 km every day, from his town to the neighboring town, which also created a great physical exhaustion for him. In the future, his aspiration is to be able to help his family financially. |

| Socio-historical dimension | The context in which the gamification experience takes place has some very specific characteristics, partly as a result of the conditions of the Spanish Curricular Diversification Program aimed at students at risk of school failure and that want to finish compulsory secondary education, which has recently disappeared as part of the latest legislative changes. The program, in which this student took part, was characterized by a lower ratio and a greater flexibility and openness of the curriculum, which allows subjects to be worked on together and to have a general teacher for several areas, conditions which are totally opposite to which was the school environment up to that moment for Hercules, characterized by ordinary lessons with between 25 to 30 students and specialist teachers for each of the subjects. |

| Gamification and ESL | Within these circumstances, the weight of the teacher who carries out the gamification experience (both in class hours and on a methodological and social level) stands out, a factor that has been highlighted as very positive by Hercules. The gamification was carried out with the whole group, dividing them into small subgroups of two students. The theme chosen for this experience was ancient civilizations, specifically Egypt and Mesopotamia. These groups were assigned tasks in relation to the curriculum of the year, after their completion they were rewarded with “tokens”, in this case soldiers or food, which gave power to their civilization. Hercules emphasizes that, despite being a complicated year in the family environment, as a result of his mother’s entry into prison, unlike previous years with this methodology he approved all the subjects, obtaining in many of them the qualification of outstanding: “I even got a high score and I passed everything, I got up to nine…”. Furthermore, and despite the fact that Hercules presents a low self-concept, identifying himself as a lazy person, he states that in that year he was sufficiently motivated to work at home if necessary, attributing his success directly to the teacher." During the period that gamification existed, Hercules and his companions showed a significant improvement in their academic results, and furthermore, individually, as our interviewee experienced a significant increase in motivation and attachment to the school environment as well as a loss of motivation and interest. However, he claims that this led, after one school year, to early school leaving. Once this experience ended, his results fell back to the levels of the past, with a detrimental effect on engagement. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guerrero-Puerta, L.; Guerrero, M.A. Could Gamification Be a Protective Factor Regarding Early School Leaving? A Life Story. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052569

Guerrero-Puerta L, Guerrero MA. Could Gamification Be a Protective Factor Regarding Early School Leaving? A Life Story. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052569

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuerrero-Puerta, Laura, and Miguel. A Guerrero. 2021. "Could Gamification Be a Protective Factor Regarding Early School Leaving? A Life Story" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052569

APA StyleGuerrero-Puerta, L., & Guerrero, M. A. (2021). Could Gamification Be a Protective Factor Regarding Early School Leaving? A Life Story. Sustainability, 13(5), 2569. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052569