Comparative Transcriptome Profile between Iberian Pig Varieties Provides New Insights into Their Distinct Fat Deposition and Fatty Acids Content

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval and Phenotypic Records

2.1.1. Ethics Approval

2.1.2. Phenotypic Records and Experimental Design

2.2. RNA-Seq

2.2.1. Sample Extraction and Sequencing Process

2.2.2. Quality Control

2.2.3. Differential Expression Analysis

2.3. Gene Variation Analysis and Association Study

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. RNA-Seq Analysis

3.1.1. Quality Control

3.1.2. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

3.1.3. Gene Ontology and Pathways Enrichment Analysis

3.2. Gene Variation Analysis and Association Study

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Metabolic Pathways | P.Val Adj + | DEG Number | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) | 8.91 × 10−65 | 61/151 | COX7B; NDUFA13; NDUFA11; COX4I1; COX4I2; NDUFA10; PIK3CD; IRS2; FASLG; PIK3CB; COX6A1; TNF; COX6A2; COX7C; PRKAG3; CASP3; AKT3; IL6R; SREBF1; ADIPOQ; NDUFC2; NDUFC1; SDHD; SDHA; SDHB; TNFRSF1A; ERN1; NDUFS8; PIK3CA; NDUFS7; NDUFS5; DDIT3; UQCRC1; NDUFS3; NDUFS2; NDUFS1; PPARA; NDUFB8; NDUFB10; NDUFB11; NDUFB2; NDUFA4L2; COX7A2; UQCR10; COX5B; COX7A1; PIK3R5; MAPK9; BCL2L11; COX3; COX2; COX1; NDUFV1; NDUFA6; INSR; EIF2AK3; EIF2S1; IL6; ITCH; UQCRQ; CYTB |

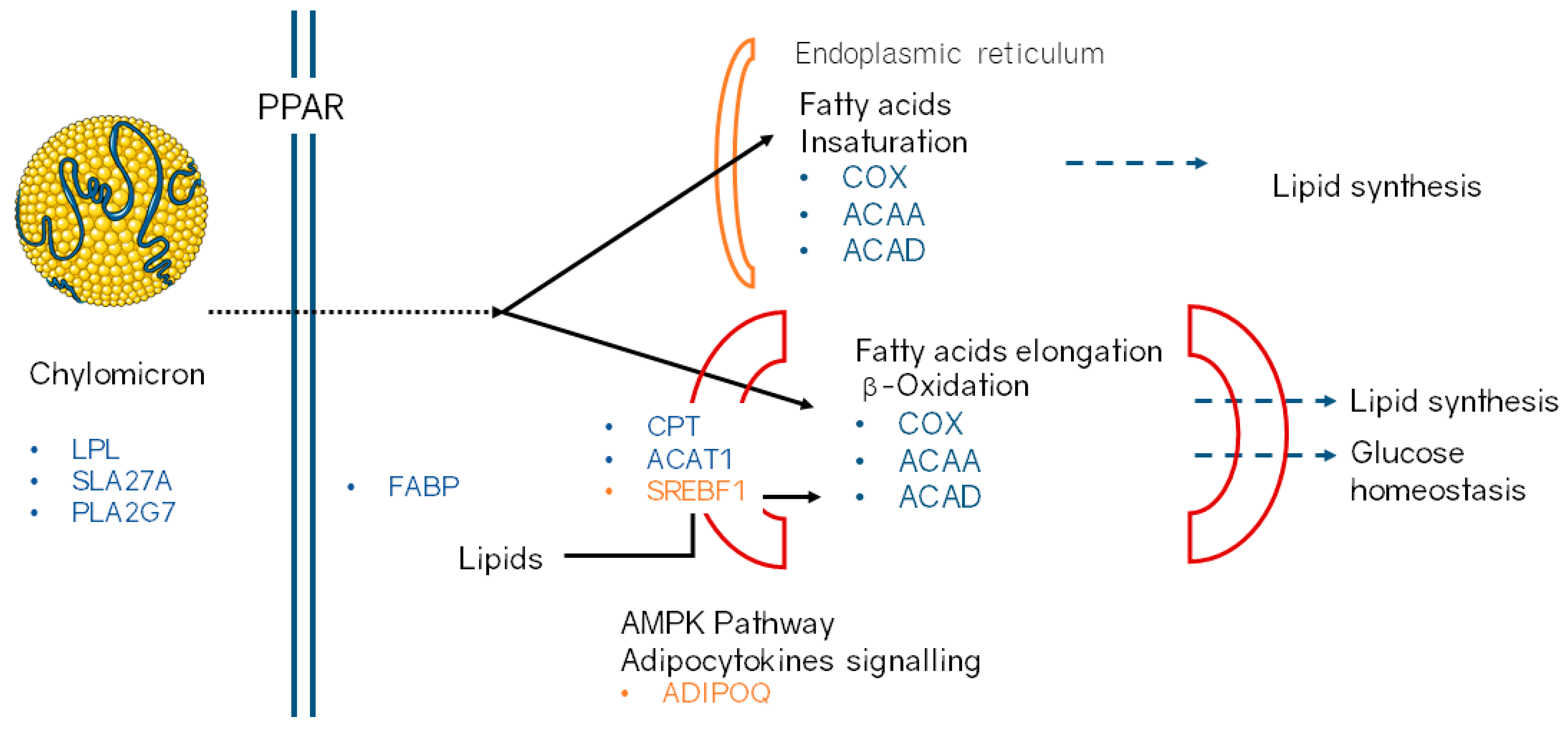

| PPAR signaling pathway | 1.66 × 10−2 | 16/69 | SLC27A1; CPT1A; ADIPOQ; SCD5; ACSL5; APOA1; LPL; ACSL3; SORBS1; CPT1B; FABP3; CPT2; FABP5; ACADL; PPARA; ACAA1 |

| Glycerophospholipid metabolism | 2.81 × 10−2 | 4/95 | PLA2G16; PLA2G4B; PLA2G10; PLD2 |

| AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications | 6.97 × 10−18 | 29/101 | SERPINE1; PIK3CD; PIK3CB; TNF; FOXO1; PIK3R5; MAPK9; CCND1; CASP3; AKT3; PIM1; PLCG1; HRAS; EGR1; TGFB2; SMAD4; EDN1; NOS3; STAT3; PRKCA; MAPK12; VEGFA; MAPK11; IL6; PIK3CA; COL4A4; COL4A5; PLCD3; PLCD4 |

| Insulin signaling pathway | 8.50 × 10−24 | 36/139 | PDE3B; CBLC; PIK3CD; CBLB; PPP1R3A; IRS2; SLC2A4; PIK3CB; CBL; FOXO1; PRKAG3; PIK3R5; GYS2; LIPE; MAPK9; PRKAR2A; AKT3; EIF4E; HRAS; SOCS4; SREBF1; PRKCI; EXOC7; INSR; BRAF; SORBS1; PHKA2; PPP1R3C; PRKAR1B; PIK3CA; PPP1R3E; HKDC1; RAPGEF1; CALM3; RAF1; SOS1 |

| Insulin resistance | 1.96 × 10−12 | 26/109 | SLC27A1; PIK3CD; PPP1R3A; IRS2; SLC2A4; PIK3CB; TNF; FOXO1; PRKAG3; PIK3R5; GYS2; MAPK9; AKT3; SREBF1; CPT1A; NOS3; INSR; STAT3; PTPN11; CPT1B; TNFRSF1A; IL6; PPP1R3C; PIK3CA; PPP1R3E; PPARA |

| Aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption | 8.65 × 10−4 | 9/39 | PIK3CA; INSR; FXYD2; PIK3CD; PRKCA; ATP1A2; PIK3CB; ATP1A1; PIK3R5 |

| Linoleic acid metabolism | 4.56 × 10−4 | 4/29 | PLA2G16; PLA2G4B; PLA2G10; ALOX15 |

| Adipocytokine signaling pathway | 1.08 × 10−6 | 19/70 | CPT1A; CHUK; ADIPOQ; STAT3; ACSL5; PTPN11; IRS2; ACSL3; SLC2A4; TNF; CPT1B; PRKAG3; CAMKK1; TNFRSF1A; CAMKK2; MAPK9; AKT3; IKBKG; PPARA |

| Arachidonic acid metabolism | 1.11 × 10−4 | 6/62 | PLA2G16; GPX2; CYP2B6; PLA2G4B; ALOX15; PLA2G10 |

| Fatty acid degradation | 7.66 × 10−6 | 16/44 | GCDH; CPT1A; ACADVL; ECHS1; ACAA2; ECI2; ACSL5; ACSL3; CPT1B; ACAT1; ALDH3A2; HADHB; ACADL; CPT2; ACAA1; ACADS |

| Fat digestion and absorption | 1.44 × 10−2 | 3/41 | SCARB1; PLA2G10; APOA1 |

| Sphingolipid metabolism | 2.77 × 10−3 | 4/47 | CERS4; GAL3ST1; SPTLC1; SGMS1 |

| Phospholipase D signaling pathway | 4.92 × 10−6 | 21/144 | INSR; PLA2G4B; ADCY4; ADCY3; PIK3CD; PRKCA; PTPN11; ADCY1; PIK3CB; ADCY8; ADCY6; PIK3R5; PLD2; PIK3CA; GRM7; AKT3; GNAS; PLCG1; RAF1; SOS1; HRAS |

| Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 3.06 × 10−3 | 3/23 | SCD5; ACAA1; ACOT4 |

| Fatty acid elongation | 2.61 × 10−4 | 4/25 | HADHB; ECHS1; ACAA2; ACOT4 |

| Gene | RR vs. TT + | RR vs. RT | RR vs. TR | TT vs. RT | TT vs. TR | RT vs. TR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fold Change * | FDR | Fold Change | FDR | Fold Change | FDR | Fold Change | FDR | Fold Change | FDR | Fold Change | FDR | |

| ACAA1 | 2.17 | 0.009 | 2.198 | 0.012 | 2.554 | 3.940 × 10−4 | 1.013 | 0.99 | 1.177 | 0.78 | 1.162 | 0.83 |

| ACAA2 | 1.891 | 0.004 | 1.525 | 0.068 | 1.6 | 0.013 | 0.806 | 0.593 | 0.846 | 0.678 | 1.05 | 0.936 |

| ACADL | 1.566 | 0.053 | 1.113 | 0.723 | 1.086 | 0.745 | 0.711 | 0.305 | 0.694 | 0.255 | 0.976 | 0.973 |

| ACADS | 1.832 | 0.005 | 1.457 | 0.105 | 1.576 | 0.019 | 0.795 | 0.551 | 0.86 | 0.71 | 1.081 | 0.886 |

| ACADVL | 1.713 | 0.001 | 1.216 | 0.266 | 1.356 | 0.028 | 0.709 | 0.096 | 0.791 | 0.323 | 1.116 | 0.741 |

| ACAT1 | 1.548 | 0.07 | 1.2 | 0.514 | 1.518 | 0.041 | 0.775 | 0.515 | 0.981 | 0.98 | 1.265 | 0.601 |

| ADIPOQ | 0.414 | 0.068 | 0.58 | 0.3 | 0.51 | 0.11 | 1.4 | 0.715 | 1.233 | 0.828 | 0.881 | 0.915 |

| COX1 | 1.869 | 0.002 | 1.323 | 0.215 | 1.798 | 0.001 | 0.707 | 0.233 | 0.962 | 0.947 | 1.36 | 0.346 |

| COX2 | 1.991 | 4.498 × 10−5 | 1.356 | 0.151 | 1.88 | 2.041 × 10−4 | 0.681 | 0.156 | 0.944 | 0.905 | 1.386 | 0.268 |

| FABP3 | 1.933 | 0.036 | 1.461 | 0.263 | 1.996 | 0.01 | 0.756 | 0.613 | 1.033 | 0.972 | 1.367 | 0.591 |

| FABP5 | 1.507 | 0.083 | 1.018 | 0.962 | 1.251 | 0.283 | 0.676 | 0.202 | 0.83 | 0.637 | 1.229 | 0.633 |

| COX3 | 1.951 | 0.001 | 1.509 | 0.047 | 1.979 | 6.130 × 10−5 | 0.773 | 0.421 | 1.014 | 0.983 | 1.312 | 0.407 |

| COX4I1 | 2.067 | 3.681 × 10−4 | 1.665 | 0.018 | 2.202 | 1.46 × 10−6 | 0.805 | 0.546 | 1.065 | 0.898 | 1.323 | 0.423 |

| COX4I2 | 2.561 | 1.882 × 10−4 | 1.874 | 0.015 | 1.99 | 0.001 | 0.732 | 0.46 | 0.777 | 0.561 | 1.062 | 0.929 |

| COX5B | 1.82 | 0.001 | 1.485 | 0.036 | 1.81 | 1.589 × 10−4 | 0.816 | 0.504 | 0.995 | 0.993 | 1.219 | 0.569 |

| COX6A1 | 1.763 | 0.006 | 1.52 | 0.053 | 1.816 | 0.001 | 0.862 | 0.727 | 1.03 | 0.963 | 1.194 | 0.677 |

| COX6A2 | 1.79 | 0.014 | 1.606 | 0.054 | 2.328 | 4.291 × 10−5 | 0.898 | 0.842 | 1.301 | 0.482 | 1.449 | 0.303 |

| COX7A1 | 1.871 | 0.011 | 1.625 | 0.054 | 2.11 | 3.85 × 10−1 | 0.868 | 0.789 | 1.128 | 0.805 | 1.299 | 0.577 |

| COX7A2 | 1.717 | 0.016 | 1.441 | 0.115 | 1.499 | 3.900 × 10−2 | 0.839 | 0.684 | 0.873 | 0.743 | 1.04 | 0.949 |

| COX7B | 1.809 | 0.003 | 1.477 | 0.06 | 1.939 | 1.03 × 10−4 | 0.817 | 0.558 | 1.072 | 0.879 | 1.313 | 0.405 |

| COX7C | 1.629 | 0.009 | 1.331 | 0.148 | 1.626 | 0.002 | 0.817 | 0.52 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 1.221 | 0.575 |

| CPT1A | 0.341 | 0.099 | 0.423 | 0.159 | 0.21 | 0.001 | 1.24 | 0.88 | 0.615 | 0.628 | 0.496 | 0.462 |

| CPT1B | 2.303 | 0.001 | 1.752 | 0.042 | 1.768 | 0.012 | 0.761 | 0.536 | 0.768 | 0.535 | 1.009 | 0.99 |

| CPT2 | 2.134 | 0.002 | 1.331 | 0.305 | 1.431 | 0.117 | 0.624 | 0.167 | 0.67 | 0.27 | 1.074 | 0.911 |

| SDHB | 1.924 | 3.681 × 10−4 | 1.528 | 0.029 | 1.964 | 3.137 × 10−5 | 0.794 | 0.445 | 1.021 | 0.971 | 1.285 | 0.425 |

| LPL | 2.173 | 0.017 | 1.52 | 0.237 | 1.763 | 0.049 | 0.699 | 0.503 | 0.811 | 0.723 | 1.16 | 0.842 |

| PLA2G7 | 1.94 | 2.985 × 10−4 | 1.999 | 9.831 × 10−5 | 1.59 | 0.003 | 1.03 | 0.956 | 0.82 | 0.496 | 0.795 | 0.471 |

| SLC27A1 | 2.396 | 0.001 | 1.544 | 0.113 | 2.091 | 0.001 | 0.644 | 0.23 | 0.873 | 0.79 | 1.354 | 0.525 |

| VEGFA | 1.768 | 0.087 | 1.27 | 0.533 | 1.671 | 0.055 | 0.718 | 0.529 | 0.945 | 0.95 | 1.316 | 0.658 |

| SREBF1 | 0.486 | 0.028 | 0.56 | 0.077 | 1.133 | 0.724 | 1.152 | 0.851 | 2.33 | 0.036 | 2.022 | 0.82 |

| Gene | SNP £ | Position | Chr € | bp $ | REF AL * | freq RR # | freq TT # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACAA1 | rs328315624 | Exon 16 | 13 | 22,965,210 | C | 0.22 | 0.56 |

| ACADVL | rs332506620 | 3′UTR | 12 | 52,582,110 | T | 0.22 | 0.63 |

| ADIPOQ | rs346045742 | Exon 2 | 13 | 124,642,893 | A | 0.59 | 0 |

| SLC27A1 | rs320952513 | 3′UTR | 2 | 60,204,605 | A | 0.32 | 0 |

| SLC27A1 | rs340138733 | Exon 3 | 2 | 60,223,824 | T | 0.21 | 0.55 |

| SLC27A1 | rs333601167 | Exon 3 | 2 | 60,223,864 | A | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| CPT1A | rs343223441 | Exon 11 | 2 | 4,272,429 | T | 0.20 | 0.55 |

| CPT1A | rs335135923 | 3′UTR | 2 | 4,292,727 | G | 0.57 | 0.33 |

| CPT1B | SSC5:155247 | 5′UTR | 5 | 155,247 | A | 0.35 | 0.58 |

| LPL | rs343665323 | Exon 1 | 14 | 4,105,043 | G | 0.04 | 0.14 |

| ACAT1 | rs326546232 | Exon 9 | 9 | 36,542,668 | C | 0.03 | 0.68 |

| CPT2 | rs345224133 | Exon 4 | 6 | 159,041,404 | C | 0.40 | 0.56 |

References

- Lopez-Bote, C.J. Sustained utilization of the Iberian pig breed. Meat Sci. 1998, 49, S17–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejeda, J.F.; Gandemer, G.; Antequera, T.; Viau, M.; García, C. Lipid traits of muscles as related to genotype and fattening diet in Iberian pigs: Total intramuscular lipids and triacylglycerols. Meat Sci. 2002, 60, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, R.; Ruiz, J.; López-Bote, C.; Martín, L.; García, C.; Ventanas, J.; Antequera, T. Influence of finishing diet on fatty acid profiles of intramuscular lipids, triglycerides and phospholipids in muscles of the Iberian pig. Meat Sci. 1997, 45, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.; De La Hoz, L.; Isabel, B.; Rey, A.I.; Daza, A.; López-Bote, C.J. Improvement of Dry-Cured Iberian Ham Quality Characteristics Through Modifications of Dietary Fat Composition and Supplementation with Vitamin E. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2005, 11, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriel, E.; Ruiz, J.; Ventanas, J.; Jesús Petrón, M.; Antequera, T. Meat quality characteristics in different lines of Iberian pigs. Meat Sci. 2004, 67, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Escriche, N.; Magallón, E.; Gonzalez, E.; Tejeda, J.F.; Noguera, J.L. Genetic parameters and crossbreeding effects of fat deposition and fatty acid profiles in Iberian pig lines. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena, R.N.; Noguera, J.L.; García-Santana, M.J.; González, E.; Tejeda, J.F.; Ros-Freixedes, R.; Ibáñez-Escriche, N. Five genomic regions have a major impact on fat composition in Iberian pigs. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corominas, J.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Castelló, A.; Muñoz, M.; Ibáñez-Escriche, N.; Folch, J.M.; Ballester, M. Evaluation of the porcine ACSL4 gene as a candidate gene for meat quality traits in pigs. Anim. Genet. 2012, 43, 714–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Fallon, J.V.; Busboom, J.R.; Nelson, M.L.; Gaskins, C.T. A direct method for fatty acid methyl ester synthesis: Application to wet meat tissues, oils, and feedstuffs. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 1511–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bumgarner, R. Overview of DNA microarrays: Types, applications, and their future. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. 2013, 101, 22.1.1–22.1.11. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggett, R.M.; Ramirez-Gonzalez, R.H.; Clavijo, B.; Waite, D.; Davey, R.P. Sequencing quality assessment tools to enable data-driven informatics for high throughput genomics. Front. Genet. 2013, 4, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- STAR Package|R Documentation. Available online: https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/STAR/versions/0.3-7 (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics (Oxf. Engl.) 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harel, A.; Dalah, I.; Pietrokovski, S.; Safran, M.; Lancet, D. Omics data management and annotation. Methods Mol. Biol. (Clifton NJ) 2011, 719, 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics (Oxf. Engl.) 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.T.; Thorvaldsdóttir, H.; Winckler, W.; Guttman, M.; Lander, E.S.; Getz, G.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 24–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, T.F.; Cánovas, A.; Canela-Xandri, O.; González-Prendes, R.; Amills, M.; Quintanilla, R. RNA-seq based detection of differentially expressed genes in the skeletal muscle of Duroc pigs with distinct lipid profiles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cánovas, A.; Quintanilla, R.; Amills, M.; Pena, R.N. Muscle transcriptomic profiles in pigs with divergent phenotypes for fatness traits. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Puig-Oliveras, A.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Corominas, J.; Estellé, J.; Pérez-Montarelo, D.; Hudson, N.J.; Casellas, J.; Folch, J.M.; Ballester, M. Differences in muscle transcriptome among pigs phenotypically extreme for fatty acid composition. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, D.M.; Rinaldo, P.; Rhead, W.J.; Tian, L.; Millington, D.S.; Vockley, J.; Hamm, D.A.; Brix, A.E.; Lindsey, J.R.; Pinkert, C.A.; et al. Targeted disruption of mouse long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase gene reveals crucial roles for fatty acid oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 15592–15597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exil, V.J.; Roberts, R.L.; Sims, H.; McLaughlin, J.E.; Malkin, R.A.; Gardner, C.D.; Ni, G.; Rottman, J.N.; Strauss, A.W. Very-Long-Chain Acyl-Coenzyme A Dehydrogenase Deficiency in Mice. Circ. Res. 2003, 93, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyman, L.R.; Tian, L.; Hamm, D.A.; Schoeb, T.R.; Gower, B.A.; Nagy, T.R.; Wood, P.A. Long term effects of high fat or high carbohydrate diets on glucose tolerance in mice with heterozygous carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1a (CPT-1a) deficiency: Diet influences on CPT1a deficient mice. Nutr. Diabetes 2011, 1, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, T.; Oelkers, P.M.; Giattina, M.R.; Worgall, T.S.; Sturley, S.L.; Deckelbaum, R.J. Differential Modulation of ACAT1 and ACAT2 Transcription and Activity by Long Chain Free Fatty Acids in Cultured Cells|Bio-chemistry. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 4756–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Uysal, K.T.; Makowski, L.; Görgün, C.Z.; Atsumi, G.; Parker, R.A.; Brüning, J.; Hertzel, A.V.; Bernlohr, D.A.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Role of the Fatty Acid Binding Protein mal1 in Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2003, 52, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serão, N.V.L.; Veroneze, R.; Ribeiro, A.M.F.; Verardo, L.L.; Braccini Neto, J.; Gasparino, E.; Campos, C.F.; Lopes, P.S.; Guimarães, S.E.F. Candidate gene expression and intramuscular fat content in pigs. J. Anim. Breed Genet. Z. Tierz. Zucht. 2011, 128, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, R.N.; Noguera, J.L.; Casellas, J.; Díaz, I.; Fernández, A.I.; Folch, J.M.; Ibáñez-Escriche, N. Transcriptional analysis of intramuscular fatty acid composition in the longissimus thoracis muscle of Iberian × Landrace back-crossed pigs. Anim. Genet. 2013, 44, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estellé, J.; Pérez-Enciso, M.; Mercadé, A.; Varona, L.; Alves, E.; Sánchez, A.; Folch, J.M. Characterization of the porcine FABP5 gene and its association with the FAT1 QTL in an Iberian by Landrace cross. Anim. Genet. 2006, 37, 589–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Puig-Oliveras, A.; Castelló, A.; Revilla, M.; Fernández, A.I.; Folch, J.M. Association of genetic variants and expression levels of porcine FABP4 and FABP5 genes. Anim. Genet. 2017, 48, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.; Bihain, B.E.; Bengtsson-Olivecrona, G.; Deckelbaum, R.J.; Carpentier, Y.A.; Olivecrona, T. Fatty acid control of lipoprotein lipase: A link between energy metabolism and lipid transport. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallardo, D.; Amills, M.; Quintanilla, R.; Pena, R.N. Mapping and tissue mRNA expression analysis of the pig solute carrier 27A (SLC27A) multigene family. Gene 2013, 515, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.K.; Gimeno, R.E.; Higashimori, T.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, H.; Punreddy, S.; Mozell, R.L.; Tan, G.; Stricker-Krongrad, A.; Hirsch, D.J.; et al. Inactivation of fatty acid transport protein 1 prevents fat-induced insulin resistance in skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Asterholm, I.W.; Kusminski, C.M.; Bueno, A.C.; Wang, Z.V.; Pollard, J.W.; Brekken, R.A.; Scherer, P.E. Dichotomous effects of VEGF-A on adipose tissue dysfunction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5874–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, E.; Freitas, P.; Costa, J.; Batista, R.; Máximo, V.; Coelho, R.; Matos-Lima, L.; Eloy, C.; Carvalho, D. Loss of mitochondrial SDHB expression: What is its role in diffuse thyroid lipomatosis? Horm. Metab. Res. Horm. Stoffwechs. Horm. Metab. 2015, 47, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Minokoshi, Y.A.; Ito, Y.; Waki, H.; Uchida, S.; Yamashita, S.; Noda, M.; Kita, S.; Ueki, K.; et al. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, L.; Jiang, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Zhang, J. Silencing of ADIPOQ efficiently suppresses preadipocyte differentiation in porcine. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013, 31, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawrocki, A.R.; Rajala, M.W.; Tomas, E.; Pajvani, U.B.; Saha, A.K.; Trumbauer, M.E.; Pang, Z.; Chen, A.S.; Ruderman, N.B.; Chen, H.; et al. Mice lacking adiponectin show decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and reduced responsiveness to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 2654–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, I.; Kojima, M.; Oe, M.; Ojima, K.; Muroya, S.; Chikuni, K. Comparing pig breeds with genetically low and high backfat thickness: Differences in expression of adiponectin, its receptor, and blood metabolites. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2019, 68, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Muscle Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Potential Candidate Genes and Pathways Affecting Intramuscular Fat Content in Pigs. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, E.; Ledoux, S.; Murphy, B.D.; Beaudry, D.; Palin, M.F. Expression of adiponectin and its receptors in swine1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 83, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobi, S.K.; Ajuwon, K.M.; Weber, T.E.; Kuske, J.L.; Dyer, C.J.; Spurlock, M.E. Cloning and expression of porcine adiponectin, and its relationship to adiposity, lipogenesis and the acute phase response. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 182, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Straub, L.G.; Scherer, P.E. Metabolic Messengers: Adiponectin. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| * Variety/Number of Genes | RR vs. TT | RR vs. RT | RR vs. TR | RT vs. TR | TT vs. RT | TT vs. TR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated | 883 | 374 | 1601 | 29 | 13 | 23 |

| Not differentially expressed | 14,685 | 15,499 | 12,690 | 16,203 | 16,200 | 16,208 |

| Downregulated | 684 | 379 | 1961 | 20 | 39 | 21 |

| Metabolic Pathways | Gene Number * | P.Val Adj + | Genes # |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPAR signaling pathway | 16/69 | 1.66 × 10−2 | SLC27A1; CPT1A; ADIPOQ; SCD5; ACSL5; APOA1; LPL; ACSL3; SORBS1; CPT1B; FABP3; CPT2; FABP5; ACADL; PPARA; ACAA1 |

| Adipocytokine signaling pathway | 19/70 | 1.08 × 10−6 | CPT1A; CHUK; ADIPOQ; STAT3; ACSL5; PTPN11; IRS2; ACSL3; SLC2A4; TNF; CPT1B; PRKAG3; CAMKK1; TNFRSF1A; CAMKK2; MAPK9; AKT3; IKBKG; PPARA |

| Fatty acid degradation | 16/44 | 7.66 × 10−6 | GCDH; CPT1A; ACADVL; ECHS1; ACAA2; ECI2; ACSL5; ACSL3; CPT1B; ACAT1; ALDH3A2; HADHB; ACADL; CPT2; ACAA1; ACADS |

| CHR € | SNP £ | Bp $ | BETA * | STAT # | p | Trait | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | 0.3254 | 2.128 | 0.03549 | Palmitol | ACAT1 |

| 12 | rs318325536 | 38,825,225 | −0.3934 | −2.397 | 0.01821 | Palmitol | ACACA |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | −0.3751 | −1.993 | 0.04866 | Palmitol | ADIPOQ |

| 2 | rs320952513 | 60,204,605 | 0.2027 | 2.147 | 0.03393 | Palmitol | SLC27A1 |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | −0.2323 | −4.325 | 3.319 × 10−5 | Palmitoleic | ACAT1 |

| 12 | rs332506620 | 52,582,110 | −0.1719 | −2.839 | 0.005389 | Palmitoleic | ACADVL |

| 13 | rs328315624 | 22,965,210 | −0.1674 | −2.493 | 0.01414 | Palmitoleic | ACAA1 |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | 0.3222 | 4.929 | 2.916 × 10−6 | Palmitoleic | ADIPOQ |

| 2 | rs343223441 | 4,272,429 | 0.3257 | 2.024 | 0.04538 | Stearic | CPT1A |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | 0.6782 | 5.136 | 1.198 × 10−6 | Stearic | ACAT1 |

| 12 | rs332506620 | 52,582,110 | 0.4897 | 3.228 | 0.001638 | Stearic | ACADVL |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | −0.8342 | −5.058 | 1.688 × 10−6 | Stearic | ADIPOQ |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | −0.6153 | −2.619 | 0.01005 | Oleic | ACAT1 |

| 12 | rs318325536 | 38,825,225 | 0.53 | 2.078 | 0.04004 | Oleic | ACACA |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | 0.6242 | 2.113 | 0.03687 | Oleic | ADIPOQ |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | −0.2122 | −2.585 | 0.01101 | Linoleic | ACAT1 |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | 0.3031 | 3.015 | 0.003186 | Linoleic | ADIPOQ |

| 2 | rs340138733 | 60,223,824 | −0.02056 | −2.25 | 0.03084 | Linolenic | SLC27A1 |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | −0.01461 | −3.008 | 0.003244 | Linolenic | ACAT1 |

| 12 | rs332506620 | 52,582,110 | −0.01111 | −2.085 | 0.03938 | Linolenic | ACADVL |

| 13 | rs328315624 | 22,965,210 | −0.01629 | −2.807 | 0.005892 | Linolenic | ACAA1 |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | 0.02618 | 4.536 | 1.457 × 10−5 | Linolenic | ADIPOQ |

| 12 | rs332506620 | 52,582,110 | 0.006203 | 2.042 | 0.04351 | Arachidonic | ACADVL |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | 1.012 | 3.717 | 0.0003164 | SFA + | ACAT1 |

| 12 | rs332506620 | 52,582,110 | 0.6879 | 2.257 | 0.02597 | SFA + | ACADVL |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | −1.208 | −3.567 | 0.0005336 | SFA + | ADIPOQ |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | −0.8293 | −3.067 | 0.002714 | MUFA + | ACAT1 |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | 0.933 | 2.752 | 0.006916 | MUFA + | ADIPOQ |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | 0.261 | 2.041 | 0.04358 | PUFA + | ADIPOQ |

| 2 | rs320952513 | 60,204,605 | 1.111 | 2.146 | 0.03406 | IMF + | SLC27A1 |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | −0.9776 | −3.21 | 0.00173 | IMF + | ACAT1 |

| 12 | rs332506620 | 52,582,110 | −0.7757 | −2.314 | 0.02249 | IMF + | ACADVL |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | 1.26 | 3.431 | 0.0008462 | IMF + | ADIPOQ |

| 9 | rs326546232 | 36,542,668 | 0.02975 | 3.413 | 0.0008961 | SFA/MUFA + | ACAT1 |

| 12 | rs332506620 | 52,582,110 | 0.02001 | 2.061 | 0.04163 | SFA/MUFA + | ACADVL |

| 13 | rs346045742 | 124,642,893 | −0.03416 | −3.133 | 0.002212 | SFA/MUFA + | ADIPOQ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villaplana-Velasco, A.; Noguera, J.L.; Pena, R.N.; Ballester, M.; Muñoz, L.; González, E.; Tejeda, J.F.; Ibáñez-Escriche, N. Comparative Transcriptome Profile between Iberian Pig Varieties Provides New Insights into Their Distinct Fat Deposition and Fatty Acids Content. Animals 2021, 11, 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030627

Villaplana-Velasco A, Noguera JL, Pena RN, Ballester M, Muñoz L, González E, Tejeda JF, Ibáñez-Escriche N. Comparative Transcriptome Profile between Iberian Pig Varieties Provides New Insights into Their Distinct Fat Deposition and Fatty Acids Content. Animals. 2021; 11(3):627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030627

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillaplana-Velasco, Ana, Jose Luis Noguera, Ramona Natacha Pena, Maria Ballester, Lourdes Muñoz, Elena González, Juan Florencio Tejeda, and Noelia Ibáñez-Escriche. 2021. "Comparative Transcriptome Profile between Iberian Pig Varieties Provides New Insights into Their Distinct Fat Deposition and Fatty Acids Content" Animals 11, no. 3: 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030627

APA StyleVillaplana-Velasco, A., Noguera, J. L., Pena, R. N., Ballester, M., Muñoz, L., González, E., Tejeda, J. F., & Ibáñez-Escriche, N. (2021). Comparative Transcriptome Profile between Iberian Pig Varieties Provides New Insights into Their Distinct Fat Deposition and Fatty Acids Content. Animals, 11(3), 627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11030627