Generating Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) in the Accommodation Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework, Hypotheses, and Conceptual Model Development

2.1. The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and of Cognitive Dissonance (TCD)

2.2. Hypotheses and Conceptual Model Development

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Context and Design

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. The Evaluation of the Measurement Model

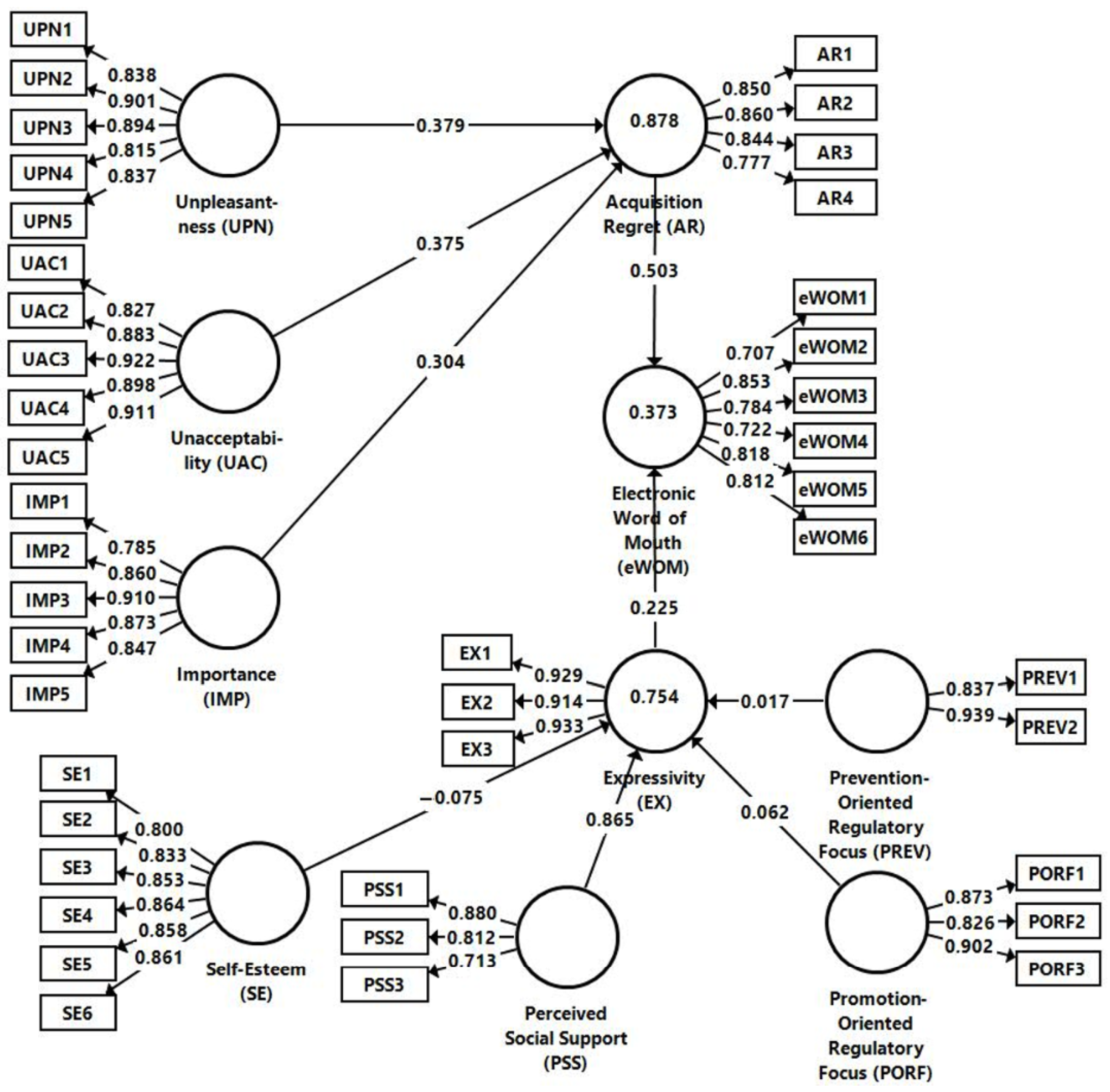

4.2. The Evaluation of the Structural Model

5. Discussion

Cultural Implications of the Research

6. Conclusions, Policy Implications, and Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartschat, M.; Cziehso, G.; Hennig-Thurau, T. Searching for word-of-mouth in the digital age: Determinants of consumers’ uses of face-to-face information, internet opinion sites, and social media. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, H.; Gunawan, T. Impact of word-of-mouth marketing on the performance of small and medium enterprises in Afghanistan. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Account. Res. 2024, 8, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G.; Opresnik, M. Principles of Marketing, 17th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, J.; Liu, B. Dynamic impact of online word-of-mouth and advertising on supply chain performance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.A.; Hartini, S.; Premananto, G.C.; Putra, R.S.; Utomo, P. Impact of positive word-of-mouth on purchase intentions and post purchase satisfaction among female customers in Pakistan. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 12158–12175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Chopra, C. Impact of social media on consumer behavior. Int. J. Creat. Res. Thoughts 2020, 8, 15527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramendia-Muneta, M.E. Spread the Word: The effect of Word-of-mouth in e-Marketing. In Commercial Communication in the Digital Age: Information or Disinformation? Siegert, G.M., Rimscha, B., Grubenmann, S., Eds.; De Gruyter Saur: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelashvili, V.; Martínez-Navalón, J.G.; DeMatos, N.; Correia, M.B. Technological transformation: The importance of E-WOM and perceived privacy in the context of opinion platforms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 205, 123472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B.; Hyde, K.F. Word-of-mouth: What we know and what we have yet to learn. J. Consum. Satisf. Dissatisfaction Complain. Behav. 2013, 26, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, S.; Khong, K.; Chong, A.; Lin, B. Persuasive electronic word-of-mouth messages in social media. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2016, 57, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. What drives consumers to spread electronic word-of-mouth in online consumer-opinion platforms. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismagilova, E.; Rana, N.P.; Slade, E.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K. A meta-analysis of the factors affecting eWOM providing behaviour. Eur. J. Mark. 2021, 55, 1067–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, D.; Toporowski, W. Reviving the experiential store: The effect of scarcity and perceived novelty in driving word-of-mouth. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2023, 51, 1065–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Zhang, K. How Multidimensional Benefits Determine Cumulative Satisfaction and eWOM Engagement on Mobile Social Media: Reconciling Motivation and Expectation Disconfirmation Perspectives. Telemat. Inform. 2024, 93, 102174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraswati, A.R.; Giantari, I.G.A.K. Brand Image Mediation of Product Quality and Electronic Word of Mouth on Purchase Decision. Int. Res. J. Manag. IT Soc. Sci. 2022, 9, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanea-Ivanovici, M.; Baber, H.; Salem, I.E.; Pana, M.-C. What do you value based on who you are? Big five personality traits, destination value and electronic word-of-mouth intentions. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2023, 25, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Lin, W.; Xiong, H. Being envied: The effects of perceived emotions on eWOM intention. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 1499–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobon, S.; García-Madariaga, J. The Influence of Opinion Leaders’ eWOM on Online Consumer Decisions: A Study on Social Influence. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 748–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, M.; Siddiqui, U.; Khan, M.; Alkandi, I.; Saxena, A.; Siddiqui, J. Creating electronic word-of-mouth credibility through social networking sites and determining its impact on brand image and online purchase intentions in India. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shaalan, A.; Jayawardhena, C. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth (ewom) on consumer behaviours. In The SAGE Handbook of Digital Marketing; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 136–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barta, S.; Gurrea, R.; Flavián, C. Consequences of consumer regret with online shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, D.B.; Vo, T.H.G.; Le, K.H. The impact of electronic word-of-mouth on brand image and buying decision: An empirical study in Vietnam tourism. Int. J. Res. Stud. Manag. 2016, 6, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, A.; Raska, D. National cultures and their impact on electronic word of mouth: A systematic review. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022, 39, 1182–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. behaviors. In Achievement and Achievement Motives: Psychological and Sociological Approaches; Spence, J.T., Ed.; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 75–146. [Google Scholar]

- Benslimane, A.; Semaoune, K. An analysis of tourist’s behavioral intention in the digital era: Using a modified model of the Reasoned Action Theory. Int. J. Mark. Commun. New Media 2021, 9, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.; Ali, R.; Hamid, S.; Akhtar, M.J.; Rahman, M.N. Demystifying the effect of social media eWOM on revisit intention post-COVID-19: An extension of theory of planed behaviour. Future Bus. J. 2022, 8, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, D.T.; Caldicott, R.W.; Kamal, M.A. Electronic Word-of-mouth (Ewom) and the travel intention of social networkers post-COVID-19: A Vietnam Case. Int. J. Prof. Bus. Rev. 2023, 8, e03856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Prakash, G.; Gupta, B.; Cappiello, G. How e-WOM influences consumers’ purchase intention towards private label brands on e-commerce platforms: Investigation through IAM (Information Adoption Model) and ELM (Elaboration Likelihood Model) Models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 187, 122199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected recent advances and applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, e3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhidayat, R.; Suroso, A.I.; Prabantarikso, M. The effect of Ewom, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and product quality on the intention to buy subsidized housing. Indones. J. Bus. Entrep. 2023, 9, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parveen, A.; Chaudhary, R. Do Attitude and Subjective Norm Mediate the Relationship Between Social Media e-WOM and Green Purchase Intention? An Empirical Investigation Using PLS-SEM. Vikalpa J. Decis. Mak. 2025, 50, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones, E. Cognitive Dissonance: Reexamining a Pivotal Theory in Psychology, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S. What Is Cognitive Dissonance Theory? 2025. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/cognitive-dissonance.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Shahani, R.; Gupta, M. Empirical investigation of application of concept of cognitive dissonance to Indian financial markets. Cognitive Dissonance to Indian Financial Markets. Gurukul Bus. Rev. (GBR) 2019, 15, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, W. Cognitive Dissonance in Leadership Trainings. In New Leadership in Strategy and Communication; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin-Sharifi, S.; Rahim-Esfidani, M. The impacts of relationship marketing on cognitive dissonance, satisfaction, and loyalty: The mediating role of trust and cognitive dissonance. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, A. Dealing with dissonance: A review of cognitive dissonance reduction. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2017, 11, e12362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, M.; Zo, H.; Lee, C.; Ceran, Y. Feeling displeasure from online social media postings: A study using cognitive dissonance theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 97, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, C.T.; Ngo, T.T.A.; Chau, H.K.L.; Tran, N.P.N. How perceived eWOM in visual form influences online purchase intention on social media: A research based on the SOR theory. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0328093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, Y.; Masuko, S.; Yamanaka, T. The effect of online reviews on consumer Cognitive Dissonance. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Kansei Eng. 2018, 17, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.K.; Chen, C.-K.; Silalahi, A.D.K. Understanding Consumers’ Post-purchase Behavior by Cognitive Dissonance and Emotions in the Online Impulse Buying Context. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI) 2021, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 10–12 August 2021; pp. 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelík, K.; Aslan, A. The impact of electronic word of mouth (eWOM) on visit intention within the framework of the Information Adoption Model: A Study on Instagram users. Int. J. Mark. Commun. New Media 2024, 12, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, G.; Martin, S.; Greiling, D. The current state of research of word-of-mouth in the health care sector. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2023, 20, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhajjar, S. An Investigation of Consumers’ Negative Attitudes Towards Banks. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2023, 26, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F.F.; Presseau, J.; Araujo-Soares, V. Time to retire the theory of planned behavior. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marikyan, D.; Papagiannidis, S.; Alamanos, E. Cognitive dissonance in technology adoption: A Study of smart home users. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 1101–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pan, Y. Mind over matter: Examining the role of cognitive dissonance and self-efficacy in discontinuous usage intentions on pan-entertainment mobile live broadcast platforms. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkin, A.; Schnall, A.; Nakata, N.; Ellis, E. Getting the message out: Social media and word-of-mouth as effective communication methods during emergencies. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2019, 34, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnawati, A.; Nadir, M.; Wardhani, W.; Setini, M. The effects of perceived ease of use, electronic word-of-mouth and content marketing on purchase decision. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Cantallops, A.; Ramon-Cardona, J.; Salvi, F. The impact of positive emotional experiences on eWOM generation and loyalty. Span. J. Mark. 2018, 22, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wang, C.L. The asymmetric impact of other-blame regret versus self-blame regret on negative word-of-mouth: Empirical evidence from China. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 1799–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen-Hai, C.; Yuan, C.-Y.; Liu, M.-T.; Fang, J.-F. The effects of outward and inward negative emotions on consumers’ desire for revenge and negative word-of-mouth. Online Inf. Rev. 2019, 43, 818–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameeni, M.S.; Ahmad, W.; Filieri, R. Brand betrayal, post-purchase regret, and consumer responses to hedonic versus utilitarian products: The moderating role of betrayal discovery mode. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 37–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Prayag, G.; Song, H. Attribution theory and negative emotions in tourism experiences. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Hwang, J. Who is an evangelist? Food tourists’ positive and negative eWOM behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philp, M.; Pyle, M.A. The “easy win” preference: Negative consumption experiences, incompetence, and the influence on subsequent unrelated loyalty behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Meng, F.; Pan, B. How does review disconfirmation influence customer online review behavior? A mixed-method investigation. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3685–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiebler, T.; Lee, N.; Brodbeck, F.C. Expectancy-disconfirmation and consumer satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2025. early access. [Google Scholar]

- Mehyar, H.; Saeed, M.; Baroom, H.; Afreh, A.A.-J.; Al-Adaileh, R. The impact of electronic word of mouth on consumers purchasing intention. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2020, 98, 183–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, T.T.A.; Bui, C.T.; Chau, H.K.L.; Tran, N.P.N. Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) on social networking sites (SNS): Roles of information credibility in shaping online purchase intention. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Jayawardhena, C.; Shukla, P.; Osburg, V.-S.; Yoganathan, V. Electronic word of mouth 2.0 (eWOM 2.0)—The evolution of eWOM research in the new age. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 176, 114587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharej, K.; Singh, N. Electronic world of mouth (eWOM) and its impact on consumer buying behavior. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Manag. 2025, 10, 7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Porral, C.; Levy-Mangin, J.-P. Situational factors in alcoholic beverage consumption: Examining the influence of the place of consumption. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2086–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, K.S.; Bolger, N.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory effectiveness of social support. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 119, 1316–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otaibi, A.A.; Moharib, B.S. The Relationship between Cognitive Dissonance and the Big-5 Factors Model of the Personality and the Academic Achievement in a Sample of Female Students at the University of Umm Al-Qura. Education 2012, 132, 607–624. [Google Scholar]

- König, T.M.; Clarke, T.B.; Hellenthal, M.; Clarke, I., III. Personality effects on WoM and eWoM susceptibilty—A cross-country perspective. Int. Mark. Rev. 2022, 39, 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronie, M.; Lăzăroiu, G.; Ștefănescu, R.; Ionescu, L.; Cocoșatu, M. Neuromanagement decision-making and cognitive algorithmic processes in the technological adoption of mobile commerce apps. Oeconomia Copernic. 2021, 12, 1033–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Rogalska, E. Generative artificial intelligence marketing, algorithmic predictive modeling, and customer behavior analytics in the multisensory extended reality metaverse. Oeconomia Copernic. 2024, 15, 825–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăzăroiu, G.; Neguriță, O.; Grecu, I.; Grecu, G.; Mitran, P.C. Generation X consumer attitudes, habits, and behaviors towards sustainability related to COVID-19. A systematic literature review. Eur. J. Int. Manag. 2025, 27, 106–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P.; Trzesniewski, K.; Lilgendahl, J.; Benet-Martinez, V.; Robins, R.W. Self and identity in personality psychology. Personal. Sci. 2021, 2, 6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Kiefer, K.; Paul, J. Marketing-to-Millennials: Marketing 4.0, customer satisfaction and purchase intention. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Soriano, F.J.; Feldman, P.S.M.; Rodríguez-Camacho, J.A.; Wright, L.T. Effect of social identity on the generation of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) on Facebook. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 173280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, L. Exploring the antecedents of trust in electronic word-of-mouth platform: The perspective on gratification and positive emotion. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 953232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, S. Cognitive Dissonance of Self-Standards: A Negative Interaction of Green Compensation and Green Training on Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior in China. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1399–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philp, M.; Pyle, M.A.; Ashworth, L. Risking the self: The impact of self-esteem on negative word-of-mouth behavior. Mark. Lett. A J. Res. Mark. 2018, 29, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N.; Lin, X.; Featherman, M.; Wang, Y. Social word-of-mouth: How trust develops in the market. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 56, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wah, J.N.K. Exploring the role of perceived social support in enhancing psychological well-being: Investigating its mediating effect and implications for mental health outcomes. Tob. Sci. Technol. 2025, 58, 2543–2581. [Google Scholar]

- Anders, S.; Tucker, J. Adult attachment style, interpersonal communication competence, and social support. Pers. Relatsh. 2000, 7, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoonen, W.; Sivunen, A.E. Finding support in emotional expression: An analysis of the implications of emotional communication on enterprise social media. Eur. Manag. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlberger, C.; Endrejat, P.; Möller, J.; Herrmann, D.; Kauffeld, S.; Jonas, E. Focus meets motivation: When regulatory focus aligns with approach/avoidance motivation in creative processes. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 807875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Jin, X.; Li, W. The influence of situational regulation on the information processing of promotional and preventive self-regulatory individuals: Evidence from eye movements. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 531147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florack, A.; Ineichen, S.; Bieri, R. The Impact of Regulatory Focus on the Effects of Two-Sided Advertising. Soc. Cogn. 2009, 27, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A.; Ried, S.; Meixner, M. State-trait interactions in regulatory focus determine impulse buying behavior. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Song, J.H.; Biswas, A. Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) generation in new media platforms: The role of regulatory focus and collective dissonance. Mark. Lett. 2014, 25, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J.; Lanaj, K.; Bono, J.; Campana, K. Daily shifts in regulatory focus: The influence of work events and implications for employee well-being. J. Organ. Behav. 2016, 37, 1293–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, X.M.; Song, L.J.; Wu, J. Is it new? Personal and contextual influences on perceptions of novelty and creativity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2017, 102, 180–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Youn, S.; Wu, G.; Kuntaraporn, M. Online word-of-mouth (or Mouse): An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2006, 11, 1104–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New-York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- SpeedGeo. 2025. Available online: https://www.speedgeo.net/reports/internet-speed-in-europe-ranking-2025#:~:text=This%20is%20the%20outcome%20of%20a%20growing,speeds%20ranging%20from%20100%20to%20120%20Mbps (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- DataReportal. Digital Romania. 2025. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2025-romania (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Eurostat, 2025. Accommodations in Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250925-1#:~:text=The%20biggest%20share%20of%20foreign,%25)%20and%20Romania%20(20.2%25) (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2014, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M.; SmartPLS 3. Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH. 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Starzyk, K.B.; Fabrigar, L.R.; Soryal, A.S.; Fanning, J.J. A Painful Reminder: The Role of Level and Salience of Attitude Importance in Cognitive Dissonance. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 35, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, R.; Hernandez Plaza, S. Perceived and Received Social Support in Two Cultures: Collectivism and Support among British and Spanish Students. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2020, 17, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y. Negative word of mouth intentions during self-service technology failures: The mediating role of regret. J. Serv. Sci. Res. 2016, 8, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nofal, R.; Bayram, P.; Emeagwali, O.L.; Al-Mu’ani, L. The effect of eWOM source on purchase intention: The moderation role of weak tie eWOM. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S.; Way, B.M. Perceived social support and chronic inflammation: The moderating role of self-esteem. Health Psychol. 2019, 38, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M.S.; Khong, K.W.; Chong, A.Y.L. Determinants of negative word-of-mouth communication using social networking sites. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Nakkawita, E.; Cornwell, J.F.M. Beyond outcomes: How regulatory focus motivates consumer goal pursuit processes. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 3, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculae, I.-A. Nation in the Name of Faith: The Use of Orthodox Christianity in Shaping Romanian Identity. Master’s Thesis, Department of Political Science, Central European University, Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Khwaja, M.; Jusoh, A. Electronic word of mouth on social media websites: Role of social capital theory, self-determination theory, and altruism. Int. J. Space-Based Situated Comput. 2019, 9, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D.; Iliescu, D.; Matu, S.; Balaszi, R. The national psychological/personality profile of Romanians: An in depth analysis of the regional national psychological/personality profile of Romanians. Rom. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 17, 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cicei, C.C. Examining the Association Between Self-Concept Clarity and Self-Esteem on a Sample of Romanian Students. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 4345–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, N.; Albu, C.; Hoffmann, S. The Westernisation of a financial reporting enforcement system in an emerging economy. Account. Bus. Res. 2020, 51, 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, M. The Applicability of Hofstede’s Theory in Romania: A Political Anthropology View. Futur. Soc. Sci. 2025, 3, 4–19. Available online: https://futurity-social.com/index.php/journal/article/view/186 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Lu, H.Y.; Wu, W.Y.; Chen, S.H. Influences on the perceived value of medical travel: The moderating roles of risk attitude, self-esteem and word-of-mouth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 19, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, H. Keep it vague? New product preannouncement, regulatory focus, and word-of-mouth. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, J.; Rosenberg, B.D.; Parks, M.J.; Siegel, J.T. The effect of informal social support: Face-to-face versus computer-mediated communication. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 1806–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.; Biddle, S.J. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior in Physical Activity: Predictive Validity and the Contribution of Additional Variables. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2002, 24, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Measure | Loading > 0.7 | VIF < 3.3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem (SE) adapted after [78]. | |||

| SE1 | Overall, I am satisfied with myself. | 0.800 | 2.250 |

| SE2 | I have a positive attitude about myself. | 0.833 | 2.524 |

| SE3 | I think I have enough positive qualities. | 0.853 | 2.656 |

| SE4 | I am capable of doing things at least as well as others. | 0.864 | 2.848 |

| SE5 | I feel I am a valuable person. | 0.858 | 2.902 |

| SE6 | I consider myself to be as valuable a person as anyone else. | 0.861 | 2.879 |

| Perceived Social Support (PSS) adapted after [79,80,81] | |||

| PSS1 | My friends are really trying to help me. | 0.880 | 1.153 |

| PSS2 | There is a special person in my life who cares about my emotions. | 0.812 | 1.550 |

| PSS3 | My family is willing to help me make decisions. | 0.713 | 1.339 |

| Expressivity (EX) adapted after [6,75]. | |||

| EX1 | I have friends with whom I can share sorrows and joys. | 0.929 | 3.128 |

| EX2 | I can talk about my problems with my friends. | 0.914 | 3.019 |

| EX3 | I can rely on my friends when needed. | 0.933 | 3.236 |

| Promotion-oriented regulatory focus (PORF) adapted after [83,87]. | |||

| PORF1 | When I was little, we did not ‘cross the line’, and we did not do things that my parents would not tolerate. | 0.873 | 2.126 |

| PORF2 | I often achieved things that motivated me to work harder. | 0.826 | 1.678 |

| PORF3 | When I was little, I followed the rules set by my parents. | 0.902 | 2.446 |

| Prevention-oriented regulatory focus (PREV) adapted after [83,87]. | |||

| PREV1 | I often do well with the activities I try. | 0.837 | 1.557 |

| PREV2 | When it comes to accomplishing things that are important to me, I notice that I do not perform as well as I would like. | 0.939 | 1.557 |

| Unpleasantness (UPN) adapted after [22,58,59]. | |||

| UPN1 | I am unhappy with the room I received. | 0.838 | 2.391 |

| UPN2 | My experience with this accommodation unit is a negative one. | 0.901 | 3.130 |

| UPN3 | The ratio of quality–price is not what I expected. | 0.894 | 3.217 |

| UPN4 | I want to stay somewhere else. | 0.815 | 1.958 |

| UPN5 | This situation is very unpleasant for me. | 0.837 | 2.250 |

| Acquisition regret (AR) adapted after [22,54,55,56]. | |||

| AR1 | I want my money back. | 0.850 | 2.393 |

| AR2 | I regret making this purchase. | 0.860 | 2.254 |

| AR3 | I will do everything I can to change this situation. | 0.844 | 2.142 |

| AR4 | I regret that I trusted the accommodation unit. | 0.777 | 1.665 |

| Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) adapted after [90]. I will… | |||

| eWOM1 | …post on my social media page how unhappy I am about this situation. | 0.707 | 1.917 |

| eWOM2 | …search the hotel’s social media page to leave a negative review regarding this situation. | 0.853 | 3.022 |

| eWOM3 | …look for social media groups (accommodation/tourism) to warn other consumers not to stay here. | 0.784 | 3.134 |

| eWOM4 | …pass on my displeasure about this accommodation to others. | 0.722 | 1.494 |

| eWOM5 | …look for travel review apps/sites to leave a negative review for the hotel. | 0.818 | 2.915 |

| eWOM6 | …leave negative reviews on the booking platform where I rented the location. | 0.812 | 2.850 |

| Unacceptability (UAC) adapted after [60]. | |||

| UAC1 | This situation is completely unacceptable. | 0.827 | 2.263 |

| UAC2 | Accommodation establishments should be prohibited from having such practices. | 0.883 | 3.151 |

| UAC3 | I have been deceived. | 0.922 | 2.446 |

| UAC4 | I will complain to the owner about this situation. | 0.898 | 2.394 |

| UAC5 | It is my right to have my situation remedied. | 0.911 | 2.787 |

| Importance (IMP) adapted after [21,41]. | |||

| IMP1 | It is especially important for me to be accommodated in an upgraded room. | 0.785 | 2.286 |

| IMP2 | My values do not allow me to accept this situation. | 0.860 | 2.946 |

| IMP3 | This situation causes me great discomfort. | 0.910 | 2.981 |

| IMP4 | This situation is landing me in a state of stress. | 0.873 | 2.900 |

| IMP5 | I am angry about this situation. | 0.847 | 3.004 |

| Construct | Cronbach Alpha > 0.7 | AVE > 0.5 | CR > 0.7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-esteem (SE) | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.94 |

| Perceived Social Support (PSS) | 0.73 | 0.65 | 0.85 |

| Expressivity (EX) | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.95 |

| Promotion-oriented regulatory focus (PORF) | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.90 |

| Prevention-oriented regulatory focus (PREV) | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.88 |

| Unpleasantness (UPN) | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.93 |

| Acquisition regret (AR) | 0.85 | 0.70 | 0.90 |

| eWOM | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.92 |

| Unacceptability (UAC) | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.95 |

| Importance (IMP) | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.93 |

| Construct | EX | IMP | UAC | UPN | PREV | eWOM | AR | PORF | SE | PSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EX | 0.926 | |||||||||

| IMP | 0.244 | 0.856 | ||||||||

| UAC | 0.323 | 0.632 | 0.889 | |||||||

| UPN | 0.337 | 0.542 | 0.823 | 0.858 | ||||||

| PREV | 0.276 | 0.160 | 0.268 | 0.304 | 0.890 | |||||

| eWOM | 0.379 | 0.597 | 0.554 | 0.415 | 0.121 | 0.784 | ||||

| AR | 0.306 | 0.746 | 0.878 | 0.852 | 0.287 | 0.572 | 0.834 | |||

| PORF | 0.564 | 0.315 | 0.483 | 0.489 | 0.303 | 0.397 | 0.443 | 0.867 | ||

| SE | 0.467 | 0.319 | 0.416 | 0.376 | 0.186 | 0.410 | 0.388 | 0.743 | 0.845 | |

| PSS | 0.866 | 0.327 | 0.396 | 0.394 | 0.295 | 0.411 | 0.374 | 0.640 | 0.571 | 0.805 |

| Paths | Path Coefficients | Standard Deviation | T-Value | p-Value | Hypotheses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR → WOM | 0.503 | 0.053 | 9.562 | 0.000 *** | H1-Confirmed |

| UPN → AR | 0.379 | 0.040 | 9.583 | 0.000 *** | H1A-Confirmed |

| UAC → AR | 0.375 | 0.041 | 9.103 | 0.000 *** | H1B-Confirmed |

| IMP → AR | 0.304 | 0.026 | 11.868 | 0.000 *** | H1C-Confirmed |

| EX → eWOM | 0.225 | 0.051 | 4.406 | 0.000 *** | H2-Confirmed |

| SE → EX | −0.075 | 0.053 | 1.400 | 0.162 n.s. | H2A-Rejected |

| PSS → EX | 0.865 | 0.030 | 28.766 | 0.000 *** | H2B-Confirmed |

| PORF → EX | 0.062 | 0.055 | 1.115 | 0.265 n.s. | H2C-Rejected |

| PREV → EX | 0.017 | 0.030 | 0.548 | 0.584 n.s. | H2D-Rejected |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mărincean, L.M.; Csorba, L.M.; Obadă, D.-R.; Dabija, D.-C. Generating Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) in the Accommodation Sector. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040328

Mărincean LM, Csorba LM, Obadă D-R, Dabija D-C. Generating Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) in the Accommodation Sector. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(4):328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040328

Chicago/Turabian StyleMărincean, Leonardo Mihai, Luiela Magdalena Csorba, Daniel-Rareș Obadă, and Dan-Cristian Dabija. 2025. "Generating Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) in the Accommodation Sector" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 4: 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040328

APA StyleMărincean, L. M., Csorba, L. M., Obadă, D.-R., & Dabija, D.-C. (2025). Generating Electronic Word of Mouth (eWOM) in the Accommodation Sector. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(4), 328. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20040328