Abstract

As virtual influencers (VIs) increasingly replace human influencers (HIs) in digital marketing, it is important to understand when and why they are perceived as effective. Building on the Match-Up Hypothesis and Mind Perception Theory, this research examines how influencer type interacts with product type to shape perceived fit and consumer responses. Across six studies (N = 1118), we find a consistent crossover pattern: VIs are viewed as a better match for utilitarian products, whereas HIs are viewed as a better match for hedonic products. This effect is explained by differences in mind perception: VIs are perceived as higher in agency, which enhances their fit with utilitarian products, while HIs are perceived as higher in experience, which enhances their fit with hedonic products. Experiments manipulating perceived agency and experience provide causal support for this mechanism. Finally, we show that while a good fit strengthens persuasion, it also heightens reputational risks, as deceptive endorsements elicit stronger negative reactions when the influencer–product fit is high. These findings clarify how mind perception underlies influencer–product matching and highlight both the persuasive potential and the risks of leveraging virtual influencers in AI-mediated consumer persuasion.

1. Introduction

Imagine a photogenic virtual influencer (VI)—an entity born of code and pixels—appearing on your Instagram feed. Rather than listing technical specifications, she endorses a pair of noise-canceling headphones with the line: “The silence these create isn’t empty; it helps me hear my own thoughts.” This moment of human-like expression raises a central puzzle for marketing scholars: How do consumers interpret an endorsement from a non-human agent claiming a deeply human, experiential benefit? Does it foster emotional connection—or trigger psychological dissonance? The answers to these questions are pivotal for understanding the evolving dynamics of persuasion in an increasingly artificial world.

The rise in VIs—AI-driven, computer-generated personas—has disrupted traditional branding. VIs promise consistency, cost efficiency, and complete creative control, enabling brands to craft messages that are always on-brand and free from the reputational risks commonly faced by human endorsers [1,2]. The commercial success of this strategy is evident worldwide. For instance, Lu do Magalu, the virtual face of a Brazilian retail giant, has become the world’s most-followed VI, driving significant sales and engagement [3]. In Japan, Imma has collaborated with over 80 brands in the past year, from luxury fashion houses to tech companies like Apple, and even delivered a TED Talk, illustrating their deep cultural and commercial integration [4].

However, while industry enthusiasm is high, academic findings remain mixed. A significant body of research has investigated consumer responses to VIs within frameworks such as source credibility, trust, and parasocial relationships (PSRs). Some studies find that HIs outperform VIs on these dimensions, as they are perceived as more authentic and emotionally resonant [5,6]. Others suggest that VIs can achieve comparable levels of credibility and foster strong PSRs, especially when they are well-designed or transparently presented as virtual [7,8]. A third stream of work finds no significant difference and highlights contexts in which VIs may seem more objective and therefore more trustworthy [9]. For instance, recent studies in 2024 have demonstrated that consumer responses are highly sensitive to a VI’s identity cues, such as gender and race, which appear to activate deep-seated stereotypes about warmth and competence [10,11]. Furthermore, the limits of hyper-realism are becoming increasingly apparent, with research continuing to highlight the risks of the “uncanny valley” where near-perfect anthropomorphism backfires [12]. This growing body of work [13] collectively points to a critical conclusion: a VI’s success is not absolute but is profoundly dependent on a ‘fit’ with the context.

This theoretical fragmentation points to a deeper issue: the lack of a cohesive framework to explain when and why VIs succeed—or fail—as brand endorsers. Much prior work has focused on whether VIs can replicate the relational outcomes of HIs, but less attention has been paid to the underlying conditions that determine their effectiveness.

One central factor known to moderate endorsement effectiveness is influencer-product fit, defined as the perceived congruence between an endorser’s characteristics and the attributes of the endorsed product [14,15]. While the Match-Up Hypothesis is well-established, its application to the novel context of VIs has remained fragmented and theoretically underdeveloped. Some studies suggest that VIs pair well with “exciting” [16] or tech-oriented brand personalities [12], while others show that they fall short in emotionally rich categories like experiential goods [5]. These inconsistencies highlight two critical research questions: First, beyond idiosyncratic products or brand personalities, is there a systematic and foundational pattern of fit for VIs versus HIs across the crucial utilitarian-hedonic dimension? Second, and more importantly, what is the core psychological mechanism that governs these often-conflicting perceptions?

To answer the first question, this study proposes a foundational pattern that moves beyond prior fragmentation: VIs are more effective endorsers of utilitarian products—those valued for functionality and efficiency—whereas HIs are more persuasive for hedonic products, which deliver emotional or sensory gratification.

Establishing what works, however, only raises a more profound question: why? Unlocking the psychological mechanism behind this fit is the central aim of our research. We argue that perceptions of fit are rooted in social cognition rather than surface-level characteristics. Drawing on Mind Perception Theory [17], we posit that consumers intuitively map an endorser’s perceived mental capacities onto a product’s core benefits. Specifically, the high agency (i.e., the capacity for planning, and competence) attributed to VIs aligns closely with the functional promise of utilitarian products. In contrast, the high experience (i.e., the capacity for feeling and emotion) attributed to HIs pairs naturally with the affective rewards of hedonic products. This mind perception account provides the first causal, mechanism-based explanation for the VI-product fit phenomenon.

However, high influencer–product fit is not always beneficial. We further explore a critical boundary condition: deceptive endorsements. We predict that when an endorsement is revealed as misleading, the very congruence that once fostered preference may backfire. Specifically, we argue that a stronger initial fit elevates consumer expectations, thus leading to a more severe sense of violation when deception is revealed, resulting in more negative brand attitudes, lower purchase intentions, and diminished forgiveness.

By identifying a systematic fit pattern between influencer type and product type, revealing its underlying psychological mechanism, and examining its paradoxical downstream effects under deception, this research offers a cohesive framework for understanding consumer responses to human versus VIs. The findings not only advance theorizing in the domains of digital persuasion, artificial intelligence, and mind perception but also provide timely managerial guidance for navigating both the opportunities and risks of algorithmic branding.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Virtual Influencers vs. Human Influencers

The emergence of VIs marks a novel paradigm in influencer marketing. Unlike HIs, who cultivate their social media presence through personal experiences and authentic interactions, VIs are computer-generated digital personas designed to imitate human-like characteristics and behaviors. Defined as “digital entities that possess anthropomorphic features and take on human-like social roles and identities, managed by either human teams or artificial intelligence algorithms” [1], these digital personas engage with audiences by expressing opinions on social issues, showcasing emotions, and sharing curated content that simulates everyday experiences [18].

From a strategic perspective, VIs offer brands unique advantages. As a novel application of artificial intelligence in creative marketing [19], their digital nature means they transcend human limitations such as fatigue or personal controversy, and their appearance and messaging are fully controllable, ensuring a consistent and risk-mitigated brand image [20,21]. This technological sophistication often leads consumers to perceive VIs as novel, innovative, and competent sources of information [12,22]. Recent empirical work corroborates this, showing that highly human-like VIs can generate a strong sense of “social presence,” making them effective communicators, particularly in interactive settings like live commerce [11,23].

However, this same non-human nature produces perceptual drawbacks and attracts criticism. In the domains of warmth and authenticity, VIs are consistently found to be deficient. Unlike HIs, who build rapport through personal stories, VIs struggle to generate a genuine sense of credibility and emotional connection [6]. This empathy gap can lead to weaker PSRs [24] and raises concerns about their credibility for products where emotional resonance is key [5]. This challenge is highlighted in recent findings where, particularly in prosocial contexts, VIs labeled as “experts” were perceived as less sincere than “non-expert” counterparts, underscoring consumers’ sensitivity to perceived emotional authenticity [25]. Moreover, the flawless, curated perfection of many VIs can provoke negative social comparisons, leading to consumer resentment and even envy [26]. This fuels broader ethical concerns about manipulation, as consumers may fear that these corporate-controlled personas are merely sophisticated tools of persuasion, blurring the lines between authentic interaction and deceptive advertising [27]. This concern is amplified in contexts where the AI’s decision-making process is opaque, highlighting the growing importance of transparency and explainability in shaping consumer responses to AI-driven marketing [28].

This inherent tension—between their perceived technological competence and their deficits in emotional authenticity and trustworthiness—lies at the heart of VI effectiveness. We argue that resolving these inconsistencies requires a framework that explicitly accounts for how this dual perception interacts with the nature of the endorsed product.

2.2. Predicting Influencer-Product Fit: Utilitarian vs. Hedonic Products

The effectiveness of an endorsement is fundamentally shaped by influencer–product fit: the perceived congruence between an endorser’s traits and a product’s features [14]. Although the Match-Up Hypothesis is well established, its application to VIs remains fragmented. We propose that a systematic pattern of fit can be predicted by mapping the core perceptual attributes of VIs and HIs onto the classic distinction between utilitarian and hedonic products [29].

Utilitarian products are valued for their functionality, practicality, and performance. Their evaluation is primarily cognitive and rational [30,31]. These instrumental attributes align conceptually with the perceived strengths of VIs. The technological, precise, and controlled nature of VIs reinforces a product’s functional value proposition [32]. Indeed, recent studies suggest VIs can be as effective as HIs for such products, partly due to their high perceived informativeness [33,34].

Conversely, hedonic products are valued for the sensory pleasure, emotional gratification, and symbolic meaning they provide [35]. Their evaluation is affective and experiential, demanding an endorser who is perceived as emotionally expressive and relatable [36]. These are the hallmark attributes more naturally associated with HIs, whose perceived authenticity and lived experiences foster stronger connections for products centered on feeling [37]. Prior research confirms that HIs are a better fit for experiential goods, as VIs are often perceived as lacking the requisite sensory and emotional depth [5,38].

Synthesizing these alignments, we predict a crossover interaction: influencer–product fit is contingent on the conceptual match between influencer type and product type.

H1.

There will be a crossover interaction between influencer type and product type on perceived fit, such that VIs will be perceived as a better fit for utilitarian (vs. hedonic) products, whereas HIs will be perceived as a better fit for hedonic (vs. utilitarian) products.

2.3. The Underlying Mechanism: A Mind Perception Account

While H1 predicts a pattern of fit, it raises a deeper theoretical question: what is the core psychological process driving these judgments? Research in human–computer interaction and marketing has often centered on constructs like anthropomorphism (the degree to which a non-human agent appears and behaves like a human) and authenticity (the perceived genuineness of an agent) to explain the effectiveness of AI endorsers [39,40,41]. The prevailing assumption is that greater anthropomorphism and authenticity lead to more favorable outcomes.

However, this focus on surface-level features may oversimplify consumer psychology and cannot fully account for the complexities of VI perception. For instance, it struggles to explain phenomena such as the “uncanny valley,” where excessive anthropomorphism backfires [42,43], or the notion of “constructed authenticity,” where VIs are seen as authentic despite being openly artificial [44]. This raises a critical question: what happens when a VI is so highly anthropomorphic that it is perceptually indistinguishable from a human? If judgments were based solely on these visual and behavioral cues, the distinction between such a VI and an HI would disappear. We argue, however, that this is not the case, because consumers respond not only to what they see (a human-like form) but also to what they know—the agent’s categorical identity as “AI” or “Human” [7,12].

To explain this deeper process, we draw on Mind Perception Theory, a foundational framework in social cognition that explains how people attribute mental states to other entities [17]. The theory posits that these attributions occur along two fundamental, orthogonal dimensions: agency and experience.

Agency refers to an entity’s perceived capacity for doing—encompassing cognitive functions like self-control, planning, memory, thought, and communication. This dimension primarily distinguishes agents capable of action (like humans) from passive objects (like rocks) and is closely associated with competence and rationality.

In contrast, Experience refers to an entity’s perceived capacity for feeling—covering the spectrum of subjective, internal states such as emotion, consciousness, pleasure, pain, and personality [17,45]. This dimension captures an entity’s ability to sense and feel, distinguishing sentient beings (like humans) from entities lacking an inner emotional world (like robots or inanimate objects). It is central to perceived warmth and emotionality.

We argue that consumers, largely unconsciously, rely on these two dimensions to assess influencer-product fit. The key lies in the systematic difference in mind perception between HIs and VIs. AI-based technologies are generally perceived as high in agency—capable of logic, planning, and efficient processing [46,47]—but low in experience, lacking genuine emotional depth [48,49].

This differential attribution provides the causal link. The enhanced fit of VIs with utilitarian products arises not merely from their technological image but because their perceived agency aligns with functional promises. Similarly, the superior fit of HIs with hedonic products stems from their perceived experience, which matches the affective promises of such products. Thus, mind perception serves as the key psychological mechanism translating influencer type into perceived fit.

H2.

Mind perception mediates the effect of influencer type on perceived influencer-product fit, such that:

H2a.

For utilitarian products, the superior fit of VIs (vs. HIs) is mediated by their higher perceived agency.

H2b.

For hedonic products, the superior fit of HIs (vs. VIs) is mediated by their higher perceived experience.

Conceptual Distinctions and Theoretical Advancement

To situate our study’s contribution, we advance a mind perception framework that offers a more foundational cognitive explanation for VI effectiveness than existing approaches. While influential constructs such as anthropomorphism, authenticity, and source credibility provide valuable insights, our framework moves beyond surface-level attributes and descriptive outcomes to address the underlying “black box” of consumer trust. We posit that consumer responses are fundamentally shaped by the attribution of a mind, which comprises two distinct capacities: agency (the capacity for planning and action) and experience (the capacity for feeling and emotion).

Our approach refines the discourse on anthropomorphism by proposing that human-likeness [11,23] primarily serves as a cue that triggers mind perception. Consumers trust a human-like VI not just because of its appearance but because they infer a mind capable of thought and feeling, thus moving the explanation from physical similarity to inferred mental capacities [43]. Similarly, we introduce a more dynamic view of authenticity. Beyond mere transparency [22,50], we argue that authenticity is perceived through a VI’s behavioral autonomy, which is a direct function of attributed agency. An openly artificial VI can thus be perceived as “authentic” if it signals an independent, self-directed mind rather than a pre-programmed script. Finally, our framework provides the foundational cognitive “why” for the Source Credibility Model and the Match-Up Hypothesis. We argue that effective matching is an intuitive alignment of the endorser’s perceived mental capacities with the product’s core benefits: high agency aligns with the functional promise of utilitarian products, while high experience aligns with the affective promise of hedonic products.

Crucially, it is also important to distinguish our framework from the classic Warmth-Competence dimensions of the Stereotype Content Model (SCM; [51]). While conceptually related, these frameworks operate at different levels. The SCM describes downstream social evaluation (judging an agent’s intent and capability), whereas Mind Perception Theory addresses the more foundational cognitive attribution of a mind itself (believing an entity can feel and act). We posit a hierarchical relationship where mind perception serves as a cognitive precursor: attributing Experience is a necessary foundation for judging Warmth, and attributing Agency is the cognitive basis for evaluating Competence. This distinction is vital for understanding non-human agents like VIs, where the primary cognitive challenge is not merely to evaluate them but to first determine what kind of mind, if any, they possess. Table 1 below summarizes these key conceptual distinctions.

Table 1.

Conceptual Comparison of Mind Perception with Related Frameworks.

2.4. The Downstream Consequences of Fit in Deceptive Contexts

We next examine the downstream consequences of fit, challenging the common assumption that high fit is invariably beneficial. We theorize that under conditions of deception, this powerful alignment becomes a double-edged sword.

To explain this, we integrate our mind perception framework with Expectancy Violation Theory (EVT) [52]. EVT provides a robust framework for examining consumer responses when an endorsement fails to meet expectations [52]. The magnitude of negative reactions is proportional to both the severity of the violation and the importance of the expectation. High influencer–product fit acts as a powerful expectation-setting mechanism, fostering trust and credibility. When such endorsements are revealed as deceptive, the resulting violation is especially jarring and triggers a stronger backlash. This amplified negative reaction should manifest across a range of critical consumer responses. Consumers should form more negative brand attitudes and show lower purchase intentions [53].

Furthermore, we move beyond these immediate brand-centric outcomes to examine a crucial relational variable: consumer forgiveness. Forgiveness is a psychologically rich construct, defined not merely as the reduction in negative emotions but as a prosocial motivational shift that signals a willingness to repair a damaged relationship [54,55]. Forgiveness is particularly important in the influencer context for two reasons. First, it signals the potential for long-term relationship recovery, which static attitude measures often fail to capture. Second, it directly shapes influencer reputation, as a lack of forgiveness can lead to unfollowing and sustained negative word-of-mouth. Given that a severe expectancy violation should make this restorative process significantly more difficult, we predict that forgiveness will be lowest in the high-fit deception scenarios. By incorporating forgiveness, our research extends the endorsement-failure literature from immediate brand outcomes to the resilience of consumer–influencer relationships.

This leads to our final set of hypotheses:

H3.

In a deceptive endorsement context, there will be a crossover interaction between influencer type and product type on consumer responses, such that negative outcomes will be most pronounced in high-fit pairings (VI-utilitarian and HI-hedonic) compared to their low-fit counterparts. Specifically:

H3a.

Consumers will exhibit less forgiveness toward the influencer in the VI-utilitarian and HI-hedonic pairing conditions.

H3b.

Consumers will form more negative brand attitudes in the VI-utilitarian and HI-hedonic pairing conditions.

H3c.

Consumers will show lower purchase intentions in the VI-utilitarian and HI-hedonic pairing conditions.

2.5. Overview of Studies

Our research unfolds across six experimental studies (two preregistered) designed to provide a comprehensive and rigorous test of our theory. Study 1 established the proposed crossover interaction between influencer type and product type on perceived fit (H1). Study 2 provided initial mediational evidence that mind perception (agency and experience) explains this effect (H2). Studies 3a and 3b experimentally manipulated agency and experience to establish causality. Finally, Studies 4a and 4b tested the downside of high fit under deception, showing that it significantly lowered forgiveness and worsened brand attitudes (H3). Collectively, this research offers convergent support for our mind perception–based model of influencer–product fit.

3. Study 1

The primary objective of Study 1 was to provide a foundational test of our core hypothesis (H1), predicting a crossover interaction between influencer type (virtual vs. human) and product type (utilitarian vs. hedonic) on perceived fit. This study was preregistered at https://aspredicted.org/cdxk-j7nr.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants and Design

Based on a power analysis conducted with G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) [56], a minimum sample of 98 participants was required to detect a medium-sized effect (f = 0.25) with 80% power (α = 0.05). We recruited 106 university students (60.4% male; M = 21.98, SD = 3.22) for this study.

The study employed a 2 (influencer type: VI vs. HI) × 2 (product type: utilitarian vs. hedonic) mixed-factorial design. Influencer type was a between-subjects factor, and product type was a within-subjects factor. The dependent variable was perceived influencer-product fit.

3.1.2. Materials

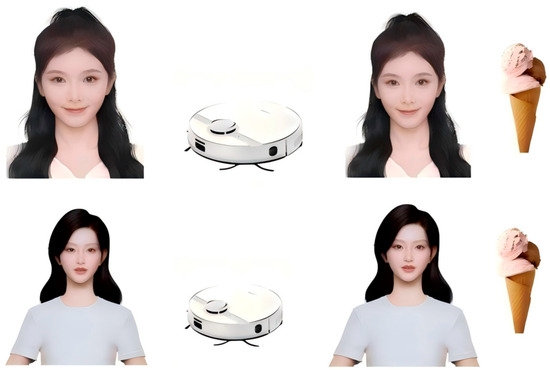

Influencer Stimuli

The images for the VIs and HIs were carefully selected to be comparable on key demographic attributes (gender: female; ethnicity: Asian). The VI images were generated using a commercial AI avatar website, while comparable HI images were sourced from publicly available, royalty-free image databases. To minimize potential confounds unrelated to the influencer’s virtual versus human nature, a rigorous standardization process was applied. All images were digitally edited to ensure a consistent neutral background, similar clothing color palette (e.g., white shirt), and comparable hair style and color. This process was designed to isolate the conceptual manipulation of influencer type (see Figure 1). The full set of visual stimuli is available in the Supplementary Materials (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Stimuli used in Study 1. The top row shows a human influencer (HI) endorsing a utilitarian (robot vacuum) and a hedonic (ice cream) product. The bottom row shows a virtual influencer (VI) in the same conditions.

Product Stimuli

A pretest (N = 105) was conducted to select one clearly utilitarian and one clearly hedonic product. Participants rated four products on a 7-point scale (1 = purely utilitarian; 7 = purely hedonic). Based on these ratings, the robot vacuum (M = 2.50, SD = 1.45) was chosen as the utilitarian stimulus and ice cream (M = 6.17, SD = 1.06) as the hedonic stimulus.

3.1.3. Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to either the VI or HI condition and read a brief definition of their assigned influencer type. Participants were first shown their assigned influencer’s image. We administered two manipulation check items: a categorical check (“Is the influencer you saw virtual or human?”) and a continuous measure of perceived anthropomorphism (“To what extent does this influencer resemble a real human?”; 1 = not at all; 7 = very much; [57]. We also measured familiarity as a potential confound (1 = not at all; 7 = very much; [58]. Subsequently, in a randomized order, participants rated perceived influencer-product fit for both products using a three-item, 7-point scale (e.g., “It makes sense to me that [influencer name] endorses this product”; 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.89) [15].

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Manipulation Checks

The manipulation of influencer type was successful. All participants correctly identified their assigned influencer type. As intended, the VI (M = 4.30, SD = 1.81) was rated as significantly less anthropomorphic than the HI (M = 6.32, SD =0.75), t (104) = −7.48, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.46. Importantly, there was no significant difference in familiarity between the VI and HI conditions, t (104) = −0.06, p = 0.950, suggesting that our stimuli were equally novel to participants.

The product type manipulation was also successful: the hedonic product (ice cream; M = 6.39, SD = 0.68) was rated significantly higher on hedonic value than the utilitarian product (robot vacuum; M = 1.76, SD = 0.95), t (105) = 31.69, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 5.60.

3.2.2. Interaction Effect of Influencer Type and Product Type on Perceived Fit

A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of influencer type, F (1, 104) = 1.93, p = 0.168, or product type, F (1, 104) = 0.26, p = 0.612. However, a significant interaction effect was found between influencer type and product type, F (1, 104) = 34.63, p < 0.001, = 0.25. For utilitarian products, participants perceived VIs (M = 5.40, SD = 0.90) as a significantly better fit compared to HIs (M = 4.79, SD = 1.26, p = 0.005). Conversely, for hedonic products, participants perceived HIs (M = 5.59, SD = 1.02) as a better fit than VIs (M = 4.45, SD = 1.59, p < 0.001).

3.3. Discussion

Study 1 provided initial support for our core hypothesis (H1), demonstrating that the perceived fit of an influencer depends on the interaction between their type (VI vs. HI) and the nature of the product (utilitarian vs. hedonic). However, a key limitation of this study was the use of different influencer and product images, which could introduce confounds related to idiosyncratic aesthetic preferences. To address this limitation and delve into the underlying mechanism, Study 2 was designed to replicate this effect while holding visual stimuli constant and measuring mind perception.

4. Study 2

Study 2 was designed to provide an empirical test of the proposed mediating role of mind perception. To achieve this, we employed a design that held all visual stimuli constant (the influencer’s face and the product image) and manipulated both influencer type and product type purely through textual descriptions. This approach allowed us to isolate the effect of the conceptual categories themselves and directly measure their influence on perceived agency and experience.

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Participants and Design

A power analysis using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) indicated that a minimum of 171 participants was required to achieve a medium effect size (effect size = 0.25; 1 − β = 0.90; α = 0.05). A total of 207 Chinese adults (58.9% female; M = 25.61, SD = 6.86) were recruited.

This study employed a 2 (influencer type: virtual vs. human) × 2 (product type: utilitarian vs. hedonic) between-subjects design. The dependent variables were participants’ perceptions of the influencer’s mind (agency and experience) and influencer–product fit.

4.1.2. Materials

Influencer Stimuli

The influencer was represented by a single, AI-generated female face (“QUI”) sourced from Miller et al. [59], which was held constant across all conditions. Influencer type was manipulated via a textual description, presenting QUI as either an “AI-generated digital human” (VI condition) or a “social media influencer” (HI condition). Full manipulation texts are provided in the Supplemental Materials (Document S1) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Experimental Stimuli in Study 2 (influencer face and massage chair).

Product Stimuli

The product was a massage chair, chosen based on a pretest (N = 22). On a 7-point scale (1 = purely utilitarian; 7 = purely hedonic), the massage chair was identified as motivationally neutral—its mean rating (M = 3.43, SD = 2.24) did not differ significantly from the scale’s midpoint of 4, t (21) = −1.14, p = 0.267. The product image was held constant across conditions. We manipulated product type by framing the massage chair with either a utilitarian description (emphasizing functional benefits like muscle recovery) or a hedonic description (emphasizing sensory benefits like relaxation and comfort), following established procedures [60].

4.1.3. Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions. The procedure unfolded in two main parts.

Participants first viewed the influencer manipulation, seeing QUI’s image accompanied by either the VI or HI description. Immediately afterward, they rated QUI’s perceived mental capacities using the 12-item mind perception scale [45]. This instrument assesses mind perception along two orthogonal dimensions. We asked participants to rate the extent to which the influencer (QUI) possessed each capacity on a 7-point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = very much). Six items measured perceived agency, which encompasses capacities for thought and action, and included: self-control, morality, planning, communication, memory, and thought (α = 0.74). The other six items measured perceived experience, which pertains to the capacity for feeling and sensation, and included: pleasure, desire, fear, pain, rage, and joy (α = 0.90). Second, they were presented with the product endorsement, read the utilitarian or hedonic description, and rated perceived influencer-product fit using the same scale as in Study 1 (α = 0.69).

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Manipulation Checks

Influencer Type

All participants correctly answered the manipulation check question, confirming the success of the influencer type manipulation. There was no significant difference in participants’ perceptions of anthropomorphism (t (205) = 0.46, p = 0.643) or familiarity (t (205) = 1.72, p = 0.086) between the virtual and human influencers.

Product Type

A significant main effect of product type on perceived utilitarian-hedonic attributes was observed. The hedonic product (M = 6.00, SD = 0.86) received higher hedonic ratings than the utilitarian product (M = 3.38, SD = 1.69), t (205) = 14.16, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.95, confirming the success of the product type manipulation.

4.2.2. Interaction Effect of Influencer Type and Product Type on Perceived Fit

A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of influencer type (F (1, 203) = 0.62, p = 0.431) or product type (F (1, 203) = 0.01, p = 0.424). However, a significant interaction effect was found, F (1, 203) = 16.91, p = 0.001, = 0.08. Simple effects analysis showed that for utilitarian products, VIs (M = 5.36, SD = 0.87) were perceived as a better fit than HIs (M = 4.93, SD = 0.75, p = 0.022). For hedonic products, HIs (M = 5.36, SD = 0.82) were perceived as a better fit (M = 4.73, SD = 1.18) than VIs, p < 0.001 (see Figure 3). These results replicate the findings of Study 1 and support Hypothesis 1.

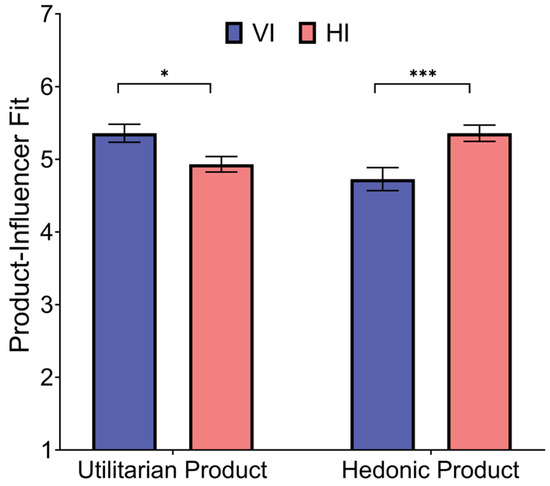

Figure 3.

Perceived product–influencer fit as a function of influencer type (virtual vs. human) and product type (utilitarian vs. hedonic) in Study 2. Error bars represent ±1 SE. * p < 0.05,*** p < 0.001.

4.2.3. Influence of Influencer Type on Mind Perception

Independent samples t-tests revealed that VIs were perceived as having higher agency (M = 5.59, SD = 0.60) than HIs (M = 5.34, SD = 0.74), t (205) = 2.74, p = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 0.37. Conversely, HIs were perceived as having higher experience (M = 4.79, SD = 0.91) than VIs (M = 3.51, SD = 1.37), t (205) = −7.90, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.10.

4.2.4. Mediating Role of Mind Perception

To test the proposed mediating roles of agency and experience, we conducted a parallel mediation analysis using the PROCESS macro (Model 4) for SPSS (version 26). We used 5000 bootstrap samples to generate 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effects. The model included influencer type (0 = VI, 1 = HI) as the independent variable, agency and experience as the parallel mediators, and influencer-product fit as the dependent variable (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Mediation effects of Influencer type on perceived (A) utilitarian and (B) hedonic influencer-product fit (Study 2). Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown.

The results showed that in the utilitarian product group, agency had a significant indirect effect (b = −0.13, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [−0.29, −0.01]), while experience did not (b = 0.10, SE = 0.11, 95% CI [−0.09, 0.33]).

In the hedonic product group, experience had a significant indirect effect (b = 1.16, SE = 0.34, 95% CI [0.54, 1.91]), while agency did not (b = −0.04, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [−0.20, 0.07]). These results indicate a differential mediation pattern: perceived agency significantly mediates the effect of influencer type on fit for utilitarian products, while perceived experience serves as the critical mediator for hedonic products.

4.2.5. Robustness Check

To further assess the robustness of our mediation results, we re-ran the parallel mediation model while including perceived anthropomorphism and familiarity as covariates. This approach ensures that the observed indirect effects are not artifacts of these related perceptual constructs.

The results confirmed the robustness of our proposed mechanism. In the hedonic product condition, the indirect effect of experience remained significant and strong even after controlling for the covariates (b = 0.39, 95% CI [0.11, 0.78]), whereas the indirect effect of agency remained nonsignificant (b = −0.08, 95% CI [−0.21, 0.03]).

For the utilitarian condition, the results provided a more nuanced picture. When controlling for familiarity, the indirect effect of agency remained significant (b = −0.13, 95% CI [−0.29, −0.01]) but was attenuated and became nonsignificant when controlling for perceived anthropomorphism (b = −0.08, 95% CI [−0.24, 0.03]). This pattern suggests that anthropomorphism functions as a perceptual antecedent to agency attribution (b = 0.32, p < 0.001) rather than as an independent predictor of perceived fit (b = −0.04, p = 0.699). In other words, consumers may infer an influencer’s competence and goal-directed capacity partly based on subtle anthropomorphic cues. However, anthropomorphism itself does not directly influence perceived influencer–product fit. This finding refines our theoretical framework by indicating that agency operates as a higher-order cognitive attribution built upon, but not reducible to, anthropomorphic perception.

4.3. Discussion

Study 2 replicated the findings of Study 1 using a single influencer face and product, confirming that VIs are perceived as a better fit for utilitarian products, while HIs align more closely with hedonic products. This supports Hypothesis 1.

By introducing mind perception (agency and experience), we further explored the underlying mechanism. The results showed that perceptions of an influencer’s agency mediated the relationship between influencer type and fit for utilitarian products, while perceptions of experience mediated the relationship for hedonic products. This suggests that agency aligns with the functional attributes of utilitarian products, whereas experience resonates with the emotional attributes of hedonic products. These findings support Hypothesis 2 and highlight the role of mind perception in shaping influencer–product fit.

5. Study 3a

Studies 3a and 3b aimed to provide causal evidence for the mediating role of mind perception in the relationship between influencer type and influencer–product fit. We employed a manipulation-of-mediation-as-a-moderator experimental design [61]. Specifically, Study 3a focused on utilitarian products and experimentally manipulated influencers’ mind perception to examine its effect on perceived fit.

5.1. Methods

5.1.1. Participants and Design

A power analysis using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7; effect size = 0.25; 1 − β = 0.9; α = 0.05) indicated a required sample size of 116. We recruited 154 Chinese participants (54.5% female; M = 24.44, SD = 6.39).

The experiment employed a 2 (influencer type: virtual vs. human) × 3 (mind perception level: control vs. high agency vs. high experience) mixed design. Influencer type was a between-subjects factor, while mind perception level was a within-subjects factor. The dependent variable was the perceived fit with a utilitarian product.

5.1.2. Materials

Three influencer images were generated using an AI-based platform under standardized criteria. A pretest (N = 32) confirmed that different faces did not differ significantly in perceived anthropomorphism or likability (ps > 0.05).

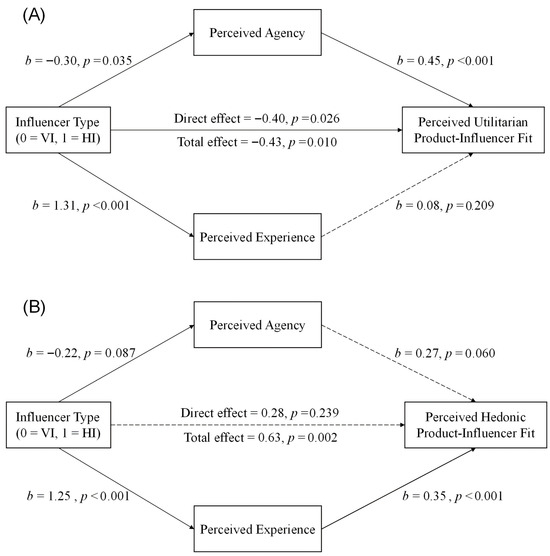

Influencer type was manipulated via a textual description, informing participants that the influencer was either a VI or an HI (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Experimental Stimuli in Study 3a (influencer face and Bluetooth headset).

Mind perception was manipulated through three distinct narrative backstories, presented sequentially in counterbalanced order: a neutral control story, a high-agency story emphasizing competence and rational achievements, and a high-experience story emphasizing emotional depth and personal feelings.

The target product was a Bluetooth headset [9], described with a utilitarian promotional message focused on functionality, performance, and battery life.

5.1.3. Procedure

Participants, assigned to either the VI or HI condition, proceeded through three blocks corresponding to the three mind perception narratives. In each block, they read a narrative and rated the influencer’s perceived agency and experience (using the scale from Study 2; α_agency = 0.84; α_experience = 0.94), then read the utilitarian ad and rated perceived influencer-product fit (using the scale from Study 1; α = 0.85).

5.2. Results and Discussion

5.2.1. Manipulation Checks

The manipulations were successful. All participants correctly identified their assigned influencer type. A repeated-measures ANOVA on the mind perception ratings confirmed the effectiveness of the narrative manipulation.

The main effect of mind perception condition was significant for agency, F (2, 306) = 87.48, p < 0.001, = 0.36. The high-agency narrative produced significantly higher agency ratings (M = 6.03, SD = 0.68) than both the control (M = 5.13, SD = 0.91) and high-experience (M = 5.45, SD = 0.84) narratives, ps < 0.001.

Similarly, the main effect of mind perception condition was significant for experience, F (2, 306) = 118.56, p < 0.001, = 0.44. The high-experience narrative yielded significantly higher experience ratings (M = 5.16, SD = 1.22) than both the control (M = 3.69, SD = 1.46) and high-agency (M = 3.54, SD = 1.51) narratives, ps < 0.001.

5.2.2. Influence of Influencer Type and Mind Perception Level on Perceived Fit

A two-way ANOVA revealed no significant main effect of influencer type on perceived fit, F (1, 152) = 3.08, p = 0.081. However, mind perception level had a significant main effect, F (2, 304) = 9.71, p < 0.001, = 0.06. Participants in the high-agency condition perceived significantly higher fit (M = 5.28, SD = 0.97) compared to those in the control (M = 4.93, SD = 1.12) and high-experience (M = 4.96, SD = 1.25) conditions.

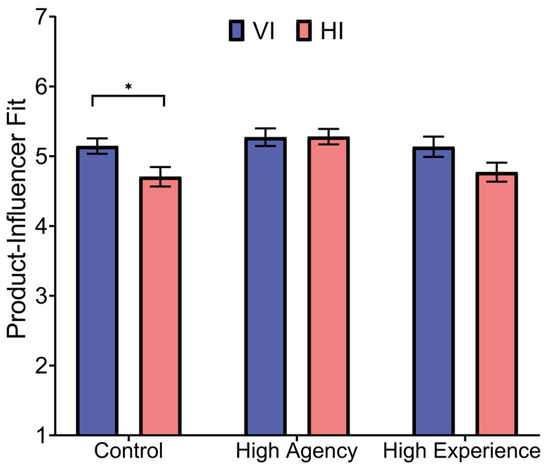

More importantly, a significant interaction effect was also found, F (2, 304) = 3.66, p = 0.027, = 0.02. In the control condition, VIs were perceived as a better fit for utilitarian products (M = 5.15, SD = 0.98) compared to HIs (M = 4.71, SD = 1.21), p = 0.014. However, this difference disappeared in the high-agency (p = 0.965) and high-experience (p = 0.070) conditions (see Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Perceived product–influencer fit for utilitarian products by influencer type (virtual vs. human) and mind perception level (control, high agency, high experience) in Study 3a. Error bars represent ±1 SE. * p < 0.05.

Study 3a provides causal evidence that perceived agency underlies the greater fit of VIs for utilitarian products. When no mind-related cues were provided, VIs were viewed as a better match. However, when both virtual and HIs were described in high-agency terms, this difference disappeared—suggesting that perceived agency, rather than influencer type per se, drives fit in utilitarian contexts.

6. Study 3b

Study 3b served as a conceptual replication and extension of Study 3a, shifting the focus to hedonic products. The primary goal was to causally demonstrate that perceived experience drives an influencer’s fit with hedonic products.

6.1. Methods

6.1.1. Participants and Design

A power analysis using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) indicated that a minimum of 116 participants were required to achieve a medium effect size (effect size f = 0.25; 1 − β = 0.90; α = 0.05). We recruited 173 Chinese participants (49.7% female; M = 24.25, SD = 6.38) were recruited.

The study employed the same 2 × 3 mixed-factorial design as Study 3a.

6.1.2. Materials and Procedure

The materials and procedure were identical to those in Study 3a, with one critical change: the target product (a Bluetooth headset) was now described with a hedonic promotional message. The new message emphasized style, sensory immersion, and emotional gratification. All measures, including perceived influencer–product fit (α = 0.85), perceived agency (α = 0.91), and perceived experience (α = 0.95), were identical to those used in Study 3a.

6.2. Results

6.2.1. Manipulation Checks

All manipulations were effective. Every participant correctly identified the assigned influencer type, confirming the success of the manipulation. A repeated-measures ANOVA confirmed that the narrative manipulations effectively influenced mind perception ratings in the intended directions (ps < 0.001). A significant main effect of mind perception level was observed for both agency (F (2, 344) = 71.37, p < 0.001, = 0.29) and experience (F (2, 306) = 118.56, p < 0.001, = 0.44).

Participants in the high-agency condition perceived significantly higher agency (M = 5.99, SD = 0.90) than those in the control (M = 5.22, SD = 1.04) and high-experience (M = 5.55, SD = 0.98) conditions. Similarly, participants in the high-experience condition perceived significantly higher experience (M = 4.96, SD = 1.64) than those in the control (M = 3.64, SD = 1.56) or high-agency (M = 3.40, SD = 1.39) conditions. These results confirm the success of the mind perception manipulation.

6.2.2. Influence of Influencer Type and Mind Perception Level on Perceived Fit

The result revealed a significant main effect of influencer type (F (1, 171) = 6.32, p = 0.013, = 0.04). The HI (M = 5.20, SD = 1.20) was significantly higher fit than VI (M = 4.85, SD = 1.08).

Mind perception level also significantly influenced perceived fit, F (2, 342) = 13.12, p < 0.001, = 0.07. Participants in the high-experience condition perceived significantly higher fit (M = 5.28, SD = 0.99) than those in the control (M = 4.82, SD = 1.28) and high-agency (M = 4.99, SD = 1.19) conditions.

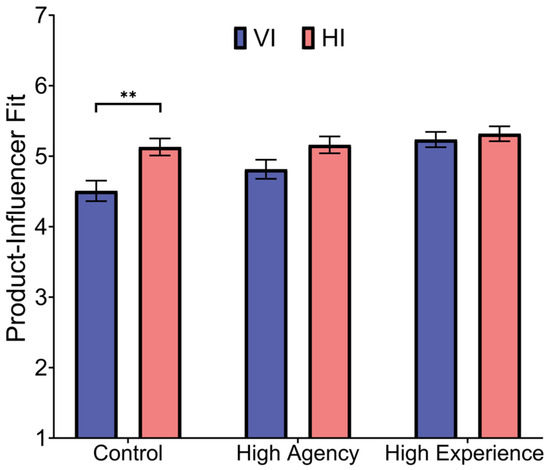

A significant interaction effect was also found, F (2, 342) = 4.47, p = 0.012, = 0.03. In the control condition, HIs were perceived as a better fit for hedonic products (M = 5.13, SD = 1.12) than VIs (M = 4.51, SD = 1.35), p = 0.001. However, this difference was no longer significant in the high-agency (p = 0.055) and high-experience (p = 0.591) conditions (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Perceived product–influencer fit for hedonic products by influencer type (virtual vs. human) and mind perception level (control, high agency, high experience) in Study 3b. Error bars represent ±1 SE. ** p < 0.01.

6.3. Discussion

Taken together, Studies 3a and 3b provide unambiguous causal evidence supporting H2. They demonstrate that the fit gap between VIs and HIs depends on their default perceived mental capacities: agency for utilitarian products and experience for hedonic products. When agency or experience was made salient, this gap disappeared. These results highlight the critical role of agency and experience as mechanisms driving perceived influencer–product fit.

7. Study 4a

Having established the foundational fit interaction and its underlying mechanism, we next turned to the critical downstream consequences. Study 4a tested whether high influencer–product fit, typically considered beneficial, could paradoxically intensify negative consumer reactions in deceptive endorsement contexts. Our primary dependent variable was consumer forgiveness. This study was preregistered at https://aspredicted.org/z7pd-vmct.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

7.1. Methods

7.1.1. Participants

A power analysis using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) indicated that a minimum of 201 participants was required to achieve a medium effect size (effect size f = 0.25; 1 − β = 0.85; α = 0.05). A total of 208 Chinese participants were recruited, with 8 excluded due to incomplete responses, resulting in 200 valid participants (50% male; M = 21.98 years, SD = 2.85).

The study employed a 2 (influencer type: virtual vs. human) × 2 (product type: utilitarian vs. hedonic) between-subjects design. The dependent variables were perceived influencer–product fit and consumer forgiveness.

7.1.2. Procedure and Materials

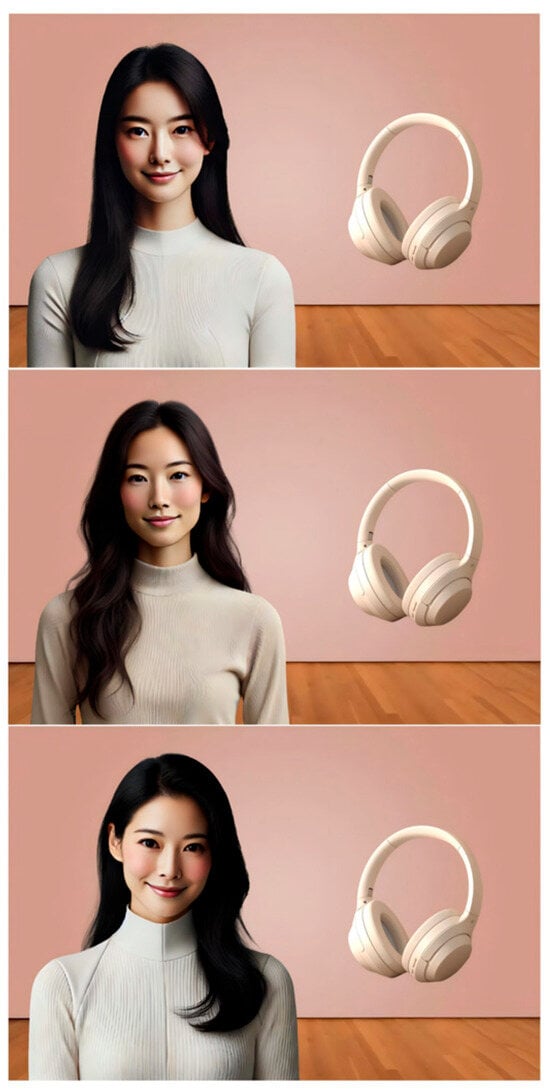

Participants viewed a promotional poster featuring a VI or HI endorsing a Bluetooth headset, which was framed as either utilitarian or hedonic (see Figure 8). They first rated perceived influencer-product fit (using the scale from Study 1; α = 0.76).

Figure 8.

Experimental Stimuli in Study 4a.

Subsequently, they were presented with a deceptive endorsement scenario. The scenario described purchasing the headset based on the influencer’s recommendation, only to find that its actual performance (utilitarian condition) or user experience (hedonic condition) was significantly different from the claims. We conceptualize this scenario as a form of deceptive advertising via false or misleading claims [62]. The core of the deception lies not in the product failing (which could be the manufacturer’s fault) but in the discrepancy between the endorser’s specific, verifiable claims (e.g., about noise-cancelation and battery life) and the product’s actual performance. By instructing participants to rule out product defects, we isolated the deception as a direct consequence of the influencer’s untruthful promotion.

Finally, participants rated their willingness to forgive the influencer on a three-item, 7-point scale (e.g., “I believe the influencer’s mistake is understandable”; 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree; α = 0.92; [63]). Manipulation checks for influencer and product type were administered at the end.

7.2. Results and Discussion

7.2.1. Manipulation Checks

The manipulations were successful. All participants correctly identified their assigned influencer type. A t-test confirmed that the utilitarian vs. hedonic product framing significantly shifted perceptions on a 7-point utilitarian-hedonic scale. Participants in the hedonic condition rated the product as significantly more hedonic (M = 5.66, SD = 0.92) than those in the utilitarian condition (M = 3.35, SD = 1.70), t (198) = 11.96, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.69.

7.2.2. Influence of Influencer Type and Product Type on Perceived Fit

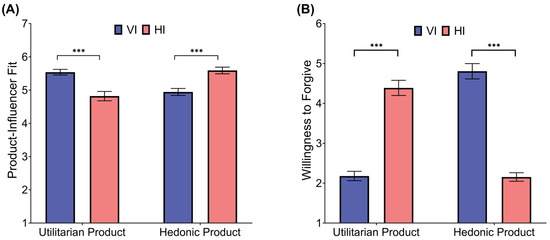

A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of influencer type (F (1, 196) = 0.12, p = 0.734) or product type (F (1, 196) = 0.66, p = 0.417). However, a significant interaction effect was found (F (1, 196) = 39.63, p < 0.001, = 0.17). Simple effects analysis showed that VIs were perceived as a better fit for utilitarian products (M = 5.54, SD = 0.61) than HIs (M = 4.82, SD = 0.97, p < 0.001), while HIs were perceived as a better fit for hedonic products (M = 5.59, SD = 0.72) than VIs (M = 4.94, SD = 0.73, p < 0.001). These results further support Hypothesis 1.

7.2.3. Influence of Influencer Type and Product Type on Forgiveness

A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of influencer type (F (1, 196) = 2.07, p = 0.152) or product type (F (1, 196) = 1.62, p = 0.205). However, a significant interaction effect was observed (F (1, 196) = 249.84, p < 0.001, = 0.56). Participants were significantly less forgiving of VIs who falsely endorsed utilitarian products (M = 2.18, SD = 0.84) than of HIs in the same context (M = 4.39, SD = 1.32, p < 0.001). Conversely, for hedonic products, participants were less forgiving of HIs (M = 2.15, SD = 0.78) than of VIs (M = 4.81, SD = 1.33, p < 0.001). These results support Hypothesis 3a (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Perceived product–influencer fit (A) and willingness to forgive (B) as a function of influencer type (virtual vs. human) and product type (utilitarian vs. hedonic) in Study 4a. Error bars represent ±1 SE. *** p < 0.001.

7.2.4. The Mediating Role of Perceived Fit

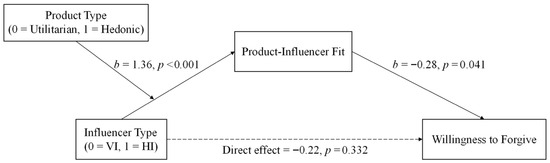

To test whether the interaction effect on forgiveness was mediated by perceived fit, we conducted a moderated mediation analysis using PROCESS Model 7 (5000 bootstrap samples; bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals). Influencer type (0 = VI, 1 = HI) was the independent variable and product type (0 = Hedonic, 1 = Utilitarian) was the moderator.

The interaction between influencer type and product type significantly predicted perceived fit (b = 1.36, p < 0.001). The index of moderated mediation was significant (Index = −0.39, SE = 0.22, 95% CI [−0.87, −0.02]), indicating that the indirect effect of influencer type on forgiveness via fit depends on product type.

Conditional indirect effects revealed: For hedonic products, the indirect effect was positive and significant (Effect = 0.20, 95% CI [0.01, 0.49]): HIs increased perceived fit, which in turn reduced forgiveness. For utilitarian products, the indirect effect was negative and significant (Effect = −0.18, 95% CI [−0.41, −0.01]): HIs decreased perceived fit, which led to greater forgiveness (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The moderated mediation effect of product–influencer fit on the relationship between influencer type and willingness to forgive.

In sum, Study 4a showed that high perceived fit heightens consumer expectations, making deception by a well-matched influencer especially damaging to forgiveness.

8. Study 4b

Study 4b had three objectives: (1) to replicate the “double-edged sword” effect using a more realistic deception scenario (behavioral inconsistency); (2) to test new product categories (apps); and (3) to examine additional managerial outcomes (brand attitude and usage intention).

8.1. Methods

8.1.1. Participants

A power analysis using G*Power (version 3.1.9.7) indicated that a minimum of 210 participants was required to achieve a medium effect size (effect size = 0.25; 1 − β = 0.95; α = 0.05). A total of 270 Chinese people were recruited (26.7% male; M = 29.53 years, SD = 8.46).

The study employed the same 2 × 2 between-subjects design as Study 4a, with apps as the product category.

8.1.2. Design and Procedure

The procedure mirrored that of previous studies. Participants first viewed an influencer profile (“Li Miquela,” manipulated as VI or HI, see Figure 11) endorsing either a utilitarian (budgeting) or hedonic (streaming) app and rated perceived fit (using the scale from Study 1; α = 0.75).

Figure 11.

Experimental Stimuli in Study 4b. Note: Chinese terms translate as follows: 关注 (Following), 粉丝 (Followers), 平台认证: 优质产品推荐博主 (Platform Certification: High-Quality Product Recommendation Blogger).

They then read a deceptive endorsement scenario framed as behavioral inconsistency [56]—a common form of inauthentic endorsement where the influencer privately admits to not using the product they publicly praise. Finally, participants evaluated their: intention to use the product, measured using a three-item scale (e.g., “How likely are you to download this app?”; 1 = very unlikely; 7 = very likely; α = 0.94; [64]); attitude toward the brand, assessed using a six-item semantic differential scale (e.g., bad/good, unfavorable/favorable; α = 0.94; [65]); and forgiveness toward the influencer, assessed with a single item (“To what extent do you forgive the influencer for the false endorsement?”, 1 = not at all; 7 = very much so).

8.2. Results

8.2.1. Manipulation Checks

The manipulations were successful. All participants correctly identified their assigned influencer type. A t-test confirmed that the utilitarian vs. hedonic product framing significantly shifted perceptions on a 7-point utilitarian-hedonic scale. Participants in the hedonic condition rated the product as significantly more hedonic (M = 5.75, SD = 1.49) than those in the utilitarian condition (M = 2.76, SD = 1.90), t (268) = 14.28, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.75.

8.2.2. Influence of Influencer Type and Product Type on Perceived Fit

A significant interaction effect was found, F (1, 266) = 31.51, p < 0.001, = 0.11. Simple effects analysis showed that VIs were perceived as a better fit for utilitarian products (M = 5.76, SD = 0.70) than hedonic products (M = 5.42, SD = 0.60, p = 0.037); while HIs were perceived as a better fit for hedonic products (M = 5.72, SD = 0.78) than utilitarian products (M = 4.77, SD = 1.44, p < 0.001). These results further support Hypothesis 1.

8.2.3. Effect on Usage Intention

A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of influencer type, F (1, 266) = 0.06, p = 0.803, or product type, F (1, 266) = 2.30, p = 0.131. However, the interaction was significant, F (1, 266) = 12.47, p < 0.001, = 0.05. For utilitarian products, participants expressed lower download intention when endorsed by VIs (M = 3.02, SD = 1.50) compared to HIs (M = 3.61, SD = 1.86, p = 0.020). For hedonic products, the reverse was true: apps endorsed by VIs (M = 3.93, SD = 1.30) elicited higher download intention than those endorsed by HIs (M = 3.25, SD = 1.18, p = 0.009). These findings support Hypothesis 3.

8.2.4. Effect on Brand Attitude

No significant main effects were observed for influencer type, F (1, 266) = 0.01, p = 0.905, or product type, F (1, 266) = 0.16, p = 0.690. However, the interaction effect was significant, F (1, 266) = 13.25, p < 0.001, = 0.05. Participants reported more favorable brand attitudes for utilitarian products endorsed by HIs (M = 4.08, SD = 1.53) than by VIs (M = 3.45, SD = 1.46, p = 0.008). For hedonic products, brands endorsed by VIs (M = 4.13, SD = 1.33) were rated more positively than those endorsed by HIs (M = 3.53, SD = 1.22, p = 0.014). These results further support Hypothesis 3.

8.2.5. Effect on Forgiveness

A 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed no significant main effects of influencer type, F (1, 266) = 0.39, p = 0.532, or product type, F (1, 266) = 0.15, p = 0.704. However, a significant interaction emerged, F (1, 266) = 17.33, p < 0.001, = 0.061. For utilitarian products, participants were less willing to forgive VIs (M = 2.94, SD = 1.71) than HIs (M = 3.93, SD = 1.83, p < 0.001). For hedonic products, participants were less forgiving of HIs (M = 3.15, SD = 1.49) than VIs (M = 3.88, SD = 1.71, p = 0.014). These findings replicate the pattern observed in Study 4a and further support Hypothesis 3.

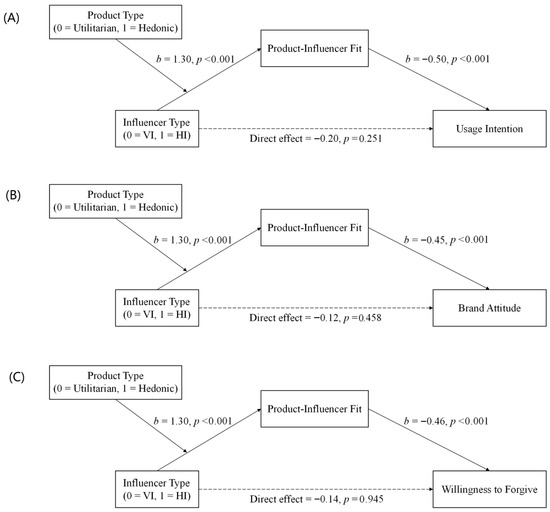

8.2.6. Moderated Mediation Analysis

To test the underlying mechanism, we conducted three moderated mediation analyses (PROCESS Model 7; 5000 bootstrap samples; bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals), one for each dependent variable: usage intention, brand attitude, and forgiveness. Influencer type (0 = Virtual, 1 = Human) and product type (0 = Hedonic, 1 = Utilitarian) were included as the independent variable and moderator, respectively. Perceived fit served as the mediator.

Table 2 presents the full results. For all three outcomes, the index of moderated mediation was statistically significant, indicating that the indirect effect of influencer type on consumer response through perceived fit depends on the product type.

Table 2.

Summary of Moderated Mediation Analyses Testing the Mediating Role of Perceived Fit.

Specifically, the conditional indirect effect of influencer type was positive and significant in the utilitarian condition, and negative and significant in the hedonic condition, across all outcomes (see Figure 12). These results suggest that the very fit that enhances endorsement effectiveness under normal conditions can amplify consumer backlash when the endorsement proves deceptive—especially when the influencer type matches the product category.

Figure 12.

Moderated mediation of product–influencer fit on (A) usage intention, (B) brand attitude, and (C) forgiveness.

8.3. Discussion

Study 4b replicated and extended the findings. Using a different deception type, new product categories, and additional outcomes, it confirmed the generalizability of the “double-edged sword” effect.

Across Studies 4a and 4b, high perceived influencer–product fit consistently amplified negative consumer responses following deceptive endorsements. Moderated mediation analyses confirmed that these effects were systematically driven by perceived fit.

Together, the two studies provide strong support for Hypothesis 3, showing that the congruence which enhances endorsement effectiveness can also magnify its negative consequences when influencer authenticity is compromised.

9. General Discussion

Across six experimental studies, this research examined how consumers evaluate the fit between influencer type (virtual vs. human) and product type (utilitarian vs. hedonic), and how such evaluations affect consumer responses in both authentic and deceptive endorsement scenarios. Drawing on Match-Up Hypothesis and Mind Perception Theory, the findings consistently showed that VIs are perceived as a better fit for utilitarian products, whereas HIs are seen as more congruent with hedonic products. Studies 1 and 2 demonstrated that consumers systematically associate VIs with high agency and HIs with high experience, which, respectively, drive perceived fit for utilitarian and hedonic products. Studies 3a and 3b provided causal evidence that mind perception—specifically, agency and experience—plays a mediating role in shaping influencer–product fit evaluations. Finally, Studies 4a and 4b revealed a downside of high perceived fit: when a false endorsement is uncovered, high fit between influencer and product leads to more negative consumer reactions, including reduced usage intention, lower brand attitude, and diminished forgiveness.

9.1. Theoretical Contributions

This research offers several important theoretical contributions to the literature on influencer marketing, human-AI interaction, and endorsement effectiveness.

First, we provide a contingency-based framework that reconciles inconsistent findings in the VI literature. Prior studies have produced mixed results regarding VI effectiveness, with some highlighting their persuasive potential [9,66] and others their social and emotional limitations [5]. Our research identifies product type (utilitarian vs. hedonic) as a critical boundary condition explaining these discrepancies. We demonstrate that the relative effectiveness of VIs versus HIs is not absolute but is contingent on the product’s core value proposition. This extends the Match-Up Hypothesis [14] by specifying a novel and systematic pattern of congruence in the digital endorsement context, thereby refining our understanding of when VIs are more or less effective than their human counterparts.

Second, this research introduces and empirically validates mind perception as the novel underlying psychological mechanism driving influencer-product fit. While prior literature has often focused on surface-level features like anthropomorphism or authenticity [41], our study delves into deeper cognitive attributions. A key finding from Study 2 underscores this distinction: even when a VI and HI were perceptually matched on anthropomorphism, their perceived mental capacities (agency vs. experience) remained starkly different, and it was these mind perceptions that drove fit judgments.

This demonstrates that mind perception is a distinct, more foundational cognitive process than mere visual realism. By providing both mediational (Study 2) and causal (Studies 3a and 3b) evidence, we are the first to ground the Match-Up Hypothesis in the cognitive science of mind perception [17] within this context, clarifying exactly which mental attributes matter for which product types.

Third, our framework complements and refines existing relational theories of digital endorsement (e.g., trust, PSRs). These theories struggle to explain our core finding: why a non-human VI, often perceived as less emotionally authentic, can outperform a human in utilitarian contexts. Our model resolves this puzzle by proposing a dual-pathway to persuasion. While a ‘warm’ relational path (driven by experience, leading to affective trust) is dominant for hedonic products, a ‘cold’ cognitive path (driven by agency, leading to cognitive trust or credibility) takes precedence for utilitarian products. Our work thus does not refute the importance of trust or PSR; rather, it delineates a critical boundary condition, showing when a competence-based evaluation overrides a relationship-based one.

Finally, our research identifies the paradoxical “double-edged sword” effect of high fit, extending persuasion theory into the domain of risk management. Whereas the conventional assumption holds that high fit is always beneficial, our findings from deception scenarios (Studies 4a and 4b) challenge this view by demonstrating that high congruence amplifies consumer backlash.

This introduces expectancy violation [52] as a critical boundary condition for the Match-Up Hypothesis. Furthermore, this insight contributes to the broader field of Human-AI Interaction (HCI) by revealing a fundamental principle: the “Task-Agent Mind Perception Alignment.” The severe backlash from an “agency betrayal” (a high-agency VI failing a functional task) suggests that the very source of an AI’s strength is also its greatest vulnerability. This principle explains why AI failures can generate disproportionate negative reactions and offers a new lens for understanding trust calibration and accountability in human-AI systems.

9.2. Practical Implications

This research offers several actionable insights for marketers, brand managers, and digital strategists. Our findings provide a psychologically grounded framework for effective influencer selection.

First, the choice between virtual and human influencers should align with product nature and marketing objectives rather than intuition. For utilitarian products, where decisions rely on functionality and performance, VIs are generally more effective because their perceived high agency creates a strong cognitive fit. In contrast, for hedonic products, evaluated based on sensory and emotional value, HIs are indispensable due to their perceived high experience.

Moreover, this principle provides a concrete decision rule for firms managing mixed product portfolios or hybrid products (e.g., smart wearables). A dual-fit strategy is recommended: assign VIs to campaigns emphasizing innovation and precision while deploying HIs for campaigns highlighting emotional appeal and lifestyle integration. For hybrid products, managers can adopt sequential campaigns in which a VI first presents technical specifications and an HI subsequently conveys the lifestyle experience, ensuring that each product attribute is communicated by the most credible source.

Second, our findings reveal a critical, counterintuitive insight for risk management: a strong influencer-product fit is a double-edged sword. While high fit boosts persuasion, it also amplifies consumer backlash in the event of an endorsement failure. This “fit-amplification effect” indicates that the most effective pairings (VI–utilitarian, HI–hedonic) are also the most reputationally vulnerable. When a VI makes a false claim about a utilitarian product, it constitutes an “agency betrayal,” violating the core expectation of competence and leading to a more severe negative reaction than a similar failure by an HI.

To mitigate reputational risks, brand managers should implement proactive transparency and accountability measures. These include clearly disclosing AI identity in marketing materials, using co-endorsement with HIs to enhance authenticity, and establishing internal verification systems for product claims made by VIs. In crisis communication, repair strategies should align with the violated expectation—emphasizing technical accuracy and responsibility for VI failures (“competence-based repair”), and emotional sincerity and empathy for HI failures (“relationship-based repair”).

Finally, our mind perception framework offers guidance for influencer and content design. Instead of pursuing a generic “human-likeness,” firms can strategically design VIs to signal the mental capacities that align with their objectives. For VIs endorsing tech-oriented products, communication style, narrative, and content should reinforce perceived agency, emphasizing analytical capabilities, precision, and objectivity. For a VI in a social or community-building role (e.g., a brand mascot), its design should incorporate cues of experience, such as simulated emotions, relatable storytelling, and vulnerability. This approach moves beyond superficial criteria like attractiveness and targets deeper psychological drivers of consumer perception.

By understanding that consumers are making inferences about an entity’s “mind,” marketers can design more resonant and effective digital spokespeople—whether fully virtual, human, or hybrid.

9.3. Limitations and Future Research

While our findings provide a robust test of the proposed theoretical framework, it is important to consider the study’s limitations, which in turn suggest promising avenues for future research. We first address potential alternative explanations for our results before discussing the boundary conditions related to our sample, methodology, and the broader theoretical implications.

A key consideration is whether our findings are driven by alternative factors such as the novelty effect of VIs or participants’ prior exposure. However, several aspects of our research design mitigate these concerns. A pure novelty effect, for instance, is unlikely to explain the specific crossover interaction pattern that we consistently observed; such an effect would likely predict a general preference for VIs, which was not the case. Regarding prior exposure, we directly controlled for familiarity in Study 1 and, more importantly, demonstrated the robustness of our core finding across six independent studies. The consistent replication of the effect across diverse stimuli and procedures makes it improbable that it is merely an artifact of idiosyncratic prior experiences.

Having addressed these potential threats to internal validity, our primary limitations concern external validity. First, our findings are based on a relatively homogeneous sample—mainly Chinese college students—which restricts demographic diversity and may limit the generalizability of our conclusions. Younger, well-educated, and tech-savvy participants may hold more favorable or sophisticated views toward AI-based agents than older or less digitally immersed populations. Future studies should therefore include more heterogeneous samples that vary in age, education, and technological familiarity to assess the robustness of these effects across demographic segments. Beyond demographic considerations, our data were also collected within a single cultural context, as all samples were drawn from China. Although this market’s rapid adoption of VIs makes it a highly relevant setting, this methodological choice raises crucial questions about cross-cultural generalizability. As we theorize, influencer-product fit is driven by attributions of agency and experience, but the perception and valuation of these mental capacities may vary across cultures. For example, individualistic Western cultures that emphasize achievement may place a greater premium on agency, whereas collectivistic East Asian cultures that value social harmony may be more sensitive to experience [67,68]. Furthermore, cultural narratives like techno-animism may shape baseline perceptions of mind in non-human agents [69]. Future research should therefore test our model across both demographically and culturally diverse samples to explore whether the weighting and perception of mind are indeed variable across populations and societies. This call for cross-cultural investigation is echoed in recent conceptual work, which suggests that consumer responses to VIs may be fundamentally shaped by cultural values such as individualism versus collectivism [40,70].

Second, beyond broad cultural values, our model could be refined by incorporating individual differences. Our design did not account for psychological traits that could moderate our effects. For example, consumers with high technological anxiety may perceive a VI’s agency as a source of unease rather than competence, thereby weakening the VI-utilitarian fit [71]. Conversely, individuals with a strong social comparison orientation might be particularly attuned to the perceived authenticity of HIs, magnifying the HI-hedonic fit [72]. Investigating these person-level moderators would provide a more nuanced understanding of consumer responses.

Third, our methodological operationalizations point to further research directions. The current research used prototypical products, but many real-world offerings (e.g., smart wearables) possess mixed utilitarian and hedonic attributes. Future work could investigate how consumers resolve fit judgments for such hybrid products and whether situational factors dynamically shift the weight assigned to agency versus experience [30]. Additionally, our studies relied on hypothetical scenarios and self-reported measures. While this approach ensures high internal validity, future research should validate these mechanisms using field experiments and behavioral data (e.g., click-through rates, actual purchases) to enhance external validity.

Finally, our framework opens new avenues at the intersection of marketing and Human-AI Interaction (HCI). Future studies could explore the effectiveness of hybrid or AI-augmented HIs, who may be perceived as high in both agency and experience, to understand how consumers resolve the cognitive dissonance from such “dual-high” profiles. Applying our “Task-Agent Mind Perception Alignment” principle to other HCI domains, such as AI in healthcare or education, could also yield valuable insights for designing more effective and trusted artificial agents. Indeed, the ethical dimensions of VI design and deployment, including issues of stereotyping and transparency, represent a critical and rapidly emerging frontier for research [73], and our mind perception framework could provide a useful lens for analyzing how different design choices impact perceptions of a VI’s morality and intent.

In summary, this research advances consumer psychology by integrating the Match-Up Hypothesis with Mind Perception Theory, revealing that consumers’ inferences about an influencer’s mind—specifically agency and experience—determine the perceived fit between influencer type and product category. By demonstrating that these cognitive attributions, rather than superficial cues such as anthropomorphism or authenticity, drive endorsement effectiveness, our work provides a unified theoretical account of why virtual and human influencers diverge in persuasive impact. This framework not only enriches our understanding of human–AI interaction but also offers a scalable psychological principle for predicting consumer responses to artificial agents across domains.

10. Conclusions

Overall, this research demonstrates that perceptions of agency and experience shape how consumers evaluate the fit between influencers and products, with important consequences for persuasion and reputational risk. By integrating mind perception with the Match-Up Hypothesis, we contribute to theories of consumer judgment and human–AI interaction while offering actionable guidance for managing the promises and pitfalls of AI-mediated marketing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jtaer20040305/s1, Figure S1. Visual Stimuli for Study 1; Figure S2. Experimental Stimuli in Study 2 (influencer face and massage chair); Figure S3. Visual Stimuli for Study 3a and 3b; Figure S4. Experimental Stimuli in Study 4a; Figure S5. Experimental Stimuli in Study 4b; Document S1: Full manipulation texts for all experimental studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.D. and Z.H.; methodology, Y.D. and Z.H.; software, Y.D., Z.H. and C.W.; validation, F.L. and Z.H., formal analysis, Y.D. and Z.H.; investigation, F.L., M.F. and W.Z.; resources, X.H.; data curation, X.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.D. and Z.H.; writing—review and editing, F.L., M.F., C.W., W.Z. and X.H.; visualization, Y.D. and Z.H.; supervision, X.H. and C.W.; project administration, X.H. and C.W.; funding acquisition, X.H. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Striving for the First-Class, Improving Weak Links and Highlighting Features (SIH) Key Discipline for Psychology in South China Normal University, the MOE Project of Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences in Universities (Grant No. 22JJD190005), Research Center for Brain Cognition and Human Development of Guangdong province, China (Grant No. 2024B0303390003), and Guangdong Planning Project of Philosophy and Social Science (Grant No. GD23XXL14).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Decla-ration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the South China Normal University (SCNU-PSY-2024-512).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data from these studies are publicly available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/5jtzg/?view_only=325ab0a99c9a4368997894368fb9d08c) (accessed on 5 August 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Byun, K.J.; Ahn, S.J. A Systematic Review of Virtual Influencers: Similarities and Differences between Human and Virtual Influencers in Interactive Advertising. J. Interact. Advert. 2023, 23, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, B. Towards an Ontology and Ethics of Virtual Influencers. Australas. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, K. Discover The Top 12 Virtual Influencers for 2025—Listed and Ranked! Influencer Marketing Hub 2021. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/virtual-influencers/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Lisa Top 10 Virtual Influencers in 2025. Storyclash. 2024. Available online: https://www.storyclash.com/blog/en/virtual-influencers/ (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Liu, F.; Lee, Y.-H. Virtually Authentic: Examining the Match-up Hypothesis between Human vs Virtual Influencers and Product Types. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 33, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Kim, W. How Virtual Influencers’ Identities Are Shaped on Chinese Social Media: A Case Study of Ling. Glob. Media China 2023, 9, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.-P.; Linda Breves, P.; Anders, N. Parasocial Interactions with Real and Virtual Influencers: The Role of Perceived Similarity and Human-Likeness. New Media Soc. 2024, 26, 3433–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, Q.N.; Thi Vu, M.H.; Tran, D.A. The Impact of ChatGPT on Tourists’ Trust and Travel Planning Intention: International Researches and Current Situation in Vietnam. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Anal. 2024, 7, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cicco, R.; Iacobucci, S.; Cannito, L.; Onesti, G.; Ceccato, I.; Palumbo, R. Virtual vs. Human Influencer: Effects on Users’ Perceptions and Brand Outcomes. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]