Abstract

Based on the self-determination theory and social presence theory, this study examined how high-tech and high-touch orientations in logistics service quality (LSQ) influence consumer satisfaction in omni-channel retailing. LSQ was modelled as two second-order constructs: high-tech orientation (timeliness, physical facilities, and ease of return) and high-touch orientation (employees’ knowledge, flexibility, and responsiveness to delivery discrepancies). Survey data from 455 consumers were analyzed using structural equation modelling. Both orientations significantly improved satisfaction, with high-tech orientation showing a slightly stronger effect, reflecting the digital literacy of the predominantly young sample. The findings extended self-determination theory and social presence theory by offering a dual-orientation perspective and practical guidance for balancing high-tech and high-touch in omni-channel logistics service design.

1. Introduction

Diversified shopping modes prompt consumers to obtain goods through different channels to compare prices, personal experiences, and convenience [1]. This cross-channel shopping behaviour reflects consumers’ increased demand for personalized services and their emphasis on comprehensive shopping experiences [2,3,4]. Omni-channel retailing can provide a seamless shopping experience through multiple channels that meet the needs of consumers in different scenarios [5,6]. Up to 73% of consumers engage with online and offline channels throughout the shopping process. This demonstrates that omni-channel shopping has become a mainstream trend [7]. Simultaneously, if brands provide a consistent service experience across channels, repeat purchase intention can increase by nearly 20% [8]. Moreover, 75% of consumers stated that delivery speed is a key factor affecting repurchase [9]. Therefore, omni-channel retailing should focus on meeting consumers’ expectations from the logistics experience and finding a balance between technology and humanized services.

In existing omni-channel retailing, the COVID-19 pandemic has spurred a trend of self-service and technology dependence in the field of consumer logistics, improving the speed and accuracy of logistics and enabling consumers to actively control logistics activities [10]. However, this dependence also brings about the problem of the insufficient humanization of logistics services, resulting in a lack of emotional connections and personalization in services [11]. Technology-driven logistics information is mostly presented in digital form and lacks the warmth of emotional communication [12]. Automated systems experience difficulty in understanding and meeting the special needs of consumers, and the system’s process management ignores users’ needs for flexible responses and personalized experiences [13]. Therefore, advanced technology can not only improve efficiency but also lead to services becoming mechanical and lacking warmth. In the future, integrating technology with humanized services will be key for improving the logistics experience [10].

The classic study on logistics satisfaction determined how logistics services affect product satisfaction in the e-commerce industry through different dimensions [14]. Service quality is subdivided into three variables: employee, operational, and technical service quality [15]. E-commerce consumer satisfaction is directly dependent on the observed logistics service aspects; among these, employee performance is significantly correlated with satisfaction [16]. Consumers prefer soft complaint response and return policies, the prompt and effective handling of complaints, professionalism, and efficient staff responses [17]. The quality of employee service can be divided into three aspects: the professionalism of service personnel, service attitude, and service response speed [14]. The quality of technical services comprises six aspects: responsiveness, reliability, security, privacy, speed, and convenience [18]. However, there is still insufficient empirical research to explain how human- and technology-related aspects of logistics service quality (LSQ) affect consumer satisfaction and behavioural intention. Therefore, this study aims to distinguish between high-tech and high-touch orientations in logistics services, which can help to capture both technological and human-centric service attributes to evaluate consumer satisfaction.

Understanding the differences in consumer demand for tech and touch quality dimensions can help companies better position themselves in the omni-channel retailing market and formulate corresponding logistics service strategies [19]. Consumers may have different expectations of humanized and technical services in e-commerce scenarios, and studying these differences can provide more targeted solutions [20]. However, a review of studies on omni-channel retailing identified a research gap in the comparison of the impact of high-tech and high-touch LSQ dimensions on consumer satisfaction. Therefore, this study expanded the self-determination theory and social presence theory, which involve the interaction between individuals and society, to distinguish between high-tech and high-touch orientation factors. It provided machine and human perspectives on the differences in satisfaction to bridge this omni-channel retailing field gap. Therefore, the research questions of this study were as follows:

RQ1: How do consumers perceive LSQ in an omni-channel retailing environment? Can these perceptions be systematically divided into high-tech and high-touch dimensions?

RQ2: What are the differences in the impact of high-tech and high-touch orientation LSQ dimensions on consumer satisfaction?

This study provided a reference for retailers to optimize logistics resource allocation and improve consumer satisfaction, emphasizes that logistics consumption is not only an economic and psychological behaviour, but also a social behaviour. Logistic services can observe from a sociological perspective how individuals maintain and build social relationships through consumption. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the literature review and model background and proposes the research hypotheses. Section 3 explains the research methodology. Section 4 analyses the results. Finally, Section 5 presents the conclusions and recommendations for future research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Logistics Service Quality in Omni-Channel Retailing

Omni-channel retailing involves the coordination of various channels and consumer interaction points to create a comprehensive experience process of shopping, entertainment, and social interaction for consumers, ensuring a consistent consumer experience and improving overall channel performance [21]. Its core objective is to unify the brand image and consumer experience, enabling consumers to enjoy consistent services, product information, and support in any channel [22]. E-commerce logistics can be defined as the systematic management of logistics activities that support online purchasing behaviour [23]. In recent years, with the rapid advancement of digital transformation, the development of e-commerce logistics has increasingly emphasized the integration of intelligent technologies [24], collaborative operations across supply chain actors [25], and a consumer-centric service orientation [26]. Risberg [27] believed that logistics practices are important in omni-channel retailing because they involve the coordinated operation of physical flows. Risberg [27] also emphasized the considerable importance of e-commerce logistics, calling it the key determinant of omni-channel retailing competitiveness. Drawing on an importance–performance analysis, Sumrit and Sowijit [28] identified logistics as one of the biggest influences on omni-channel satisfaction. Therefore, intelligent, coordinated, and humanized logistics services can improve consumer service satisfaction and loyalty in omni-channel retailing.

In recent studies, LSQ has substantially influenced consumer satisfaction and loyalty in omni-channel retailing [29,30]. Murfield et al. [31] measured LSQ from the perspective of omni-channel retailing, proposed a three-dimensional framework (timeliness, conditions, and availability) to measure LSQ, and explored its impact on consumer purchase satisfaction. A subsequent study confirmed that LSQ comprises different key dimensions. After Vasić et al. [32] determined how logistics services affect product satisfaction in the e-commerce industry through eight dimensions, Rashid and Rasheed [16] verified six perspectives in different geographical locations and confirmed that observable dimensions such as product and information quality have a significant positive impact on product satisfaction. Zhang and Huang [14] verified the correlation between poor LSQ and consumer complaints from the opposite six dimensions. Among these, service attitude was related to many aspects of consumer complaints; however, the empirical evidence explaining how the people contact part of LSQ affects consumers’ satisfaction and behavioural intentions was inadequate [30]. Equally focusing on the high-tech and high-touch service divisions can enhance the understanding of the influencing factors and importance of LSQ in omni-channel retailing.

The evaluation dimensions involved in existing research mainly focus on the service performance of the distribution link and pay insufficient attention to the service quality of other links in the logistics process. With the deep participation of consumers in the logistics process, the interaction between consumers and logistics services has extended to multiple links beyond distribution. Related research points out that consumers have begun to intervene in the front-end links of logistics to jointly create service value [33]. In addition, the omni-channel retailing model is different from the traditional single e-commerce channel. Its integrated characteristics provide consumers with a consistent shopping experience in the entire process of purchase, exchange and return. It is necessary to ensure the availability of goods in each channel and provide differentiated logistics services [27]. Therefore, in the complex scenario of omni-channel retailing, it is difficult to fully reflect the essential characteristics of omni-channel logistics services by only emphasizing indicators such as the timeliness of the distribution link and the integrity of goods [34]. At present, few studies have explored the role of the front-end logistics service process and the human dimension in the quality of omni-channel retailing logistics services and their importance. Based on this, the research on logistics service quality needs to build a more refined and systematic theoretical framework to meet the practical needs of omni-channel retailing.

2.2. High-Tech and High-Touch Orientations

This study uses the SERVQUAL framework to comprehensively understand logistics service quality (LSQ). SERVQUAL, developed by Parasuraman et al. [35] which was considered the most appropriate framework to cover the entire logistics service process [30]. includes five customer-based service quality dimensions: tangibility, responsiveness, empathy, reliability, and assurance. However, traditional logistics services are aimed at single or multi-channel independent operations, and information between channels is not interoperable. The uniqueness of omni-channel retail is that consumers can switch freely across channels [2,3,4]. Therefore, the ultimate speed and accuracy pursued by omni-channel retail requires traditional dimensions to evaluate the quality of tangibility digital interfaces (physical facilities) and the processing reliability of intelligent systems (timeliness) [10]. At the same time, channel responsiveness (responsiveness to delivery discrepancies) requires that each dimension must be able to evaluate cross-channel service consistency and coordination capabilities, rather than isolated single-channel performance [5,6]. The differences in omni-channel retail service expectations include manual service elements, assurance (employees’ knowledge), and empathy (ease of return) [11]. Consumer dominance highlights the need for flexibility, as omnichannel consumers expect greater choice and control throughout their shopping journey [13]. Therefore, this integrated framework of six dimensions retains the SERVQUAL model’s systematic assessment of the fundamental elements of service quality while also capturing the unique value proposition of the omnichannel logistics environment through the addition of the flexibility dimension, making the model more targeted and explanatory.

Previous service quality research provides a strong theoretical foundation for understanding how value is created through both technological systems and human interaction. Grönroos [36] distinguished between technical quality, which represents what the customer receives as the outcome of the service, and functional quality, which reflects how the service is delivered during the interaction process. This distinction suggests that customers evaluate service quality not only by its results but also by the process through which those results are achieved. Similarly, Brady and Cronin [37] proposed a hierarchical model that integrates interaction quality, physical environment quality, and outcome quality, demonstrating that both system-based and human-centred components jointly shape customer perceptions. Building on these theoretical foundations, this study conceptualizes logistics service quality in omni-channel retailing through two overarching orientations: high-tech and high-touch.

High-tech orientation refers to a retailer’s strategic emphasis on the use of advanced technologies, automated systems, and digital platforms to improve LSQ. In the context of omni-channel retailing, this orientation is closely associated with service attributes: timeliness, physical facilities, and ease of return, which are all concluded in the SERVQUAL framework. Do et al. [38] included timeliness and ease of return in logistic service technical quality. Timeliness reflects the ability to deliver orders within the promised timeframe, often supported by real-time tracking systems that allow consumers to monitor shipment progress through mobile applications. For example, same-day or next-day delivery logistics time commitment services rely on intelligent routing and automated warehouses to enhance consumers’ perception of delivery reliability. Ease of return emphasizes the convenience of product return mechanisms, which are increasingly integrated into omni-channel platforms. Online platforms that support online return applications and door-to-door pickup services allow consumers to easily return products, which can improve the overall reverse logistics experience. A strong high-tech orientation enables retailers to achieve large-scale service standardization, operational efficiency, and process optimization, thus strengthening competitiveness in highly dynamic omni-channel environments. Chen et al. [39] also stressed that ease of return can improve the quality of logistics service technology. Physical facilities highlight the role of state-of-the-art warehouses and transportation infrastructure in ensuring operational efficiency and accuracy. The improved delivery accuracy and efficiency of the smart logistics park equipped with robots and automated sorting systems fully demonstrates the technological empowerment capabilities and intelligent operation advantages of advanced facilities.

By contrast, high-touch orientation captures consumers’ perceptions of the human and relational aspects of logistics services. In omni-channel retailing, this orientation is reflected in attributes: employees’ knowledge, flexibility, and responsiveness to delivery discrepancies, which are also concluded in the SERVQUAL framework [30]. While flexibility is selected as a very important factor that has been repeatedly associated with customer experience and service. Reichhart and Holweg [40] emphasizes that employee knowledge and responsiveness to delivery influences logistic service interaction quality. Knowledge refers to frontline staff’s expertise and experience in addressing consumer problems, which enables them to provide accurate information and effective solutions. For instance, well-trained customer service agents can explain logistics delays and recommend suitable alternatives, then enhance consumer trust. Responsiveness to delivery discrepancies highlights the ability to promptly resolve issues such as damaged, delayed, or incorrect shipments. Flexibility reflects the retailer’s capacity to accommodate consumers’ diverse needs, by providing different options for engaging with staff, such as changing delivery times or offering customized delivery services, including evening or holiday delivery [41,42,43,44]. Leading logistics service providers have established efficient and transparent claims and compensation mechanisms to minimize consumer dissatisfaction. Thus, high-touch orientation plays a crucial role in shaping consumer satisfaction. Please see Table 1 for the classification of these service quality attributes.

Table 1.

Classification of omni-channel retailing logistics service quality attributes.

2.3. Hypothesis Development

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), proposed by Deci and Ryan [50], posits that the degree to which an individual’s psychological needs are satisfied influences their intrinsic motivation, thereby impacting their behaviour and mental health. In SDT, psychological needs arise not only from external factors but also from various sociological factors. Satisfaction of SDT’s three fundamental psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—leads to greater well-being, improved performance, and psychological well-being. Autonomy stems from the ability to make decisions at one’s own pace, competence stems from the ability to effectively navigate the environment, and relatedness stems from a sense of connection and belonging to others [51]. Consumers prefer high-quality technology and mechanical means in logistics services because these satisfy their autonomy needs—allowing personal-paced decision-making and technology control while fostering social belonging through interpersonal interaction. Thus, high-tech oriented social relationship reconstruction provides a crucial sociological perspective for understanding logistics service quality.

E-commerce research on omni-channel retailing largely focuses on technology and digital transformation, distribution network design, inventory and capacity management, delivery planning, and execution to improve logistics efficiency [5,52]. Retail research and practice require a distribution network design for direct-to-consumer and store delivery to adapt and predict demand, ensure availability, meet different delivery times, and reduce costs for each channel [53]. High-tech orientation systems can respond flexibly to changes in market demand [52], and automated equipment and systems can accelerate inventory management and order processing [54]. Moreover, real-time package tracking information allows consumers to track the order status at any time [55]. Efficient technology and automated processes can reduce logistics costs, which translate into price benefits for consumers [54]. Efficient, accurate, and seamless logistics experience is one of the expectations of modern consumers [56]. However, whether high-quality technology and mechanical means directly affect consumer satisfaction remains unclear.

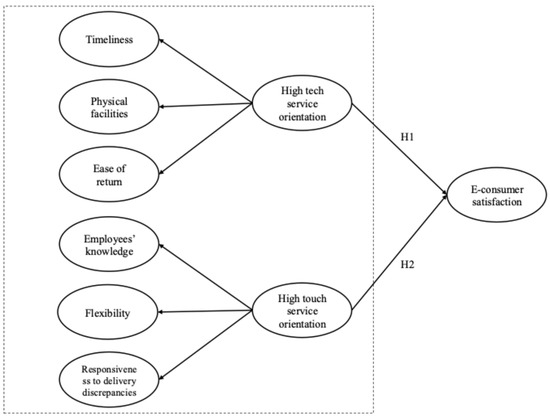

H1.

The high-tech orientation service aspects of logistics (timeliness, physical facilities, and ease of return) positively influence satisfaction.

Social Presence Theory, proposed by short [57], posits that the characteristics of communication media can influence users’ perceived level of social presence, thereby impacting their communication behaviour and the quality of interaction. In social presence theory, the psychological experience of virtual and real-world communication is influenced by the participants’ degree of physical presence. Three fundamental influencing factors—immediacy, multiple cues, and personalization—can enhance the subjective experience of interaction. Immediacy stems from the real-time nature of information transmission, multiple cues from multisensory information such as vision and hearing, and personalization stems from the ability to convey personal emotions and attitudes [58]. Consumers prefer authentic, intimate, and immediate interpersonal interactions in logistics services because this satisfies their immediacy needs—enabling direct and rapid problem-solving, enhancing communication through multi-sensory experiences, and perceiving emotional care and service attitudes through human interaction. Thus, high-touch oriented social relationship reconstruction provides a crucial sociological perspective for understanding logistics service quality.

Although technology and mechanized operations can significantly improve logistics efficiency in omni-channel retailing, human interaction still plays a key role in consumers’ perceptions of service quality [59]. Understanding consumer behaviour within the omni-channel retailing context is a popular research agenda, emphasizing consumers’ motivations, attitudes, and behaviours towards omni-channel retailing [60]. Individuals tend to form impressions more easily through human interaction; therefore, positive employee interaction can enhance consumers’ identification with logistics services [61]. Consumer satisfaction can be affected by the following factors: the consumer service response speed, problem-solving skills, and attitude [62]; the attitude and professionalism of the delivery personnel in the last mile of delivery [63] the service quality and expertise of store employees when picking up goods from stores; and contact with employees who specialize in handling returns or exchanges. However, the analysis of consumer behaviour in the logistics segment remains focused on general LSQ [28,30]. Therefore, another research gap concerns the impact of different interpersonal interaction service qualities on consumers.

H2.

The high-touch orientation service aspects of logistics (employees’ knowledge, flexibility, and responsiveness to delivery discrepancies) positively influence satisfaction.

As illustrated in Figure 1, this study conceptualized high-tech and high-touch orientations as two higher-order constructs that jointly shape omni-channel LSQ. Building on this conceptual framework, the following section develops the research hypotheses to empirically test the effects of high-tech and high-touch orientations on consumer satisfaction in omni-channel retailing.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Methodology

Consumers’ satisfaction with e-commerce directly depends on logistics services. Investigating logistics satisfaction is an important means of evaluating consumers’ perceptions of LSQ [16]. In previous studies, logistics satisfaction has mostly been measured through questionnaire surveys, and the number of samples that fully considered the complexity of the model was collected to obtain the satisfaction data. To assess the validity and reliability of the questionnaire structure, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated [64]. Different models can effectively evaluate the role of different logistics service dimensions in enhancing consumers’ satisfaction and can provide empirical evidence for improving these services.

The PROCESS model was used to test whether the impact of delivery options (independent variable) on reuse intention (dependent variable) was mediated by consumer satisfaction (mediating variable) [41]. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to verify the impact of different dimensions of logistics procedure service quality on product satisfaction [65]. This research methodology was transferred to the post-epidemic context and focused on the impact of e-commerce platform quality on consumer satisfaction and repurchase intention [66]. Savastano et al. [67] used demographic variables as moderating variables in the SEM. In a specific container shipping sector, service quality improved consumer satisfaction by enhancing relationship quality [68]. The advantage of SEM is that it can handle complex relationships between variables, providing a more accurate representation of the effect of LSQ on e-consumer satisfaction. [30]. Although existing research has used SEM to reach certain conclusions, further explorations of other potential variables and their applicability to various logistics links in different market environments are required.

3.1. Questionnaire Design

This study used a structured questionnaire comprising two main sections to collect data. The first section measured consumers’ perceptions of the six key dimensions of omni-channel retailing LSQ as well as consumers’ overall satisfaction. The second section gathered demographic information from the respondents, including their age, gender, education level, and frequency of omni-channel retailing usage.

The measurement items for the service quality dimensions were adapted from established scales in the literature, primarily based on the SERVQUAL framework, with appropriate modifications to reflect the characteristics of omni-channel logistics services. Specifically, six first-order constructs were included: timeliness, physical facilities, ease of return, employees’ knowledge, flexibility, and responsiveness to delivery discrepancies. Satisfaction was introduced as the dependent variable to assess consumers’ overall evaluation of the service.

All items were rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), to ensure accurate quantification of perceptions. Table 2 lists the constructs, measurement items, and the corresponding literature sources. To ensure that the respondents fully understood the content, an introduction to omni-channel retailing and its logistics services was provided at the beginning of the questionnaire.

Table 2.

Constructs and measurement items.

3.2. Data Collection and Sample Profile

Before the main survey, a pilot test was conducted online through the Credamo, a professional research platform, with 50 respondents to assess the clarity and relevance of the questionnaire items. Based on this feedback, minor revisions were made to improve the reliability and validity. The formal survey was conducted online through the same professional data collection platform using a random sampling approach to enhance representativeness.

Participation was restricted to respondents residing in Shanghai, China, who were reached via a QR code and online survey links. To ensure the relevance of the sample, the respondents were required to answer two screening questions before proceeding: (1) whether they were long-term residents of Shanghai and (2) whether they had previous experience with omni-channel retailing shopping. Only those who answered ‘yes’ to both questions were permitted to complete the entire questionnaire. An attention check was embedded to identify careless or inattentive responses, and questionnaires failing this check were excluded from the dataset.

To ensure data quality, additional filters were applied to remove “speeders” (respondents who completed the survey in less than one-third of the median time) and “straight-liners” (respondents giving identical answers across items). These data collection and validation procedures follow the best-practice guidelines proposed by Schoenherr et al. [69], which emphasize the importance of rigorous respondent screening and attention checks when using professional online research panels to ensure empirical reliability. As Credamo’s automated system manages invitation distribution and completion tracking, it is not feasible to calculate a conventional response rate based on invitations versus completions. Thus, this study reports the effective valid response rate after quality screening, ensuring methodological transparency and data integrity. In total, 750 questionnaires were distributed, and 455 valid responses were retained for analysis, yielding an effective response rate of 60.6%. The average completion time was approximately eight minutes.

To assess potential non-response bias, early and late respondents were compared across key demographic variables and the dependent variable (consumer satisfaction). The results indicated no significant differences in age (p = 0.42), education level (p = 0.37), or monthly income (p = 0.45) between the two groups, suggesting that non-response bias was minimal.

A post hoc statistical power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 to assess the adequacy of the sample size. Based on a total of 455 respondents, an alpha level of 0.05, and an observed medium-to-large effect size (f2 = 0.30), the achieved statistical power exceeded 0.95. This indicates that the sample size was sufficient for detecting structural relationships within the hierarchical SEM model. Hence, the current sample provides adequate statistical precision and supports the robustness of the reported findings.

Table 3 presents the demographic profiles of the respondents. The sample comprised 64.4% female and 35.6% male participants. Most participants were aged between 19 and 30 years (60.7%), followed by those aged between 31 and 40 years (28.4%), indicating a largely younger population. Regarding education, more than 83% of the respondents had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Furthermore, over half of the respondents (50.1%) reported using omni-channel retailing services more than 48 times in the past year, demonstrating extensive shopping experience.

Table 3.

Sample profile.

These sample characteristics were consistent with the research context. As omni-channel retailing relies heavily on digital technologies, younger and better-educated consumers are more likely to adopt such services. Thus, their dominance in the sample enhanced the explanatory power and applicability of the research findings, particularly for understanding consumer perceptions of LSQ in a digitalized environment.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

To verify the dimensional structure of the measurement model and assess the suitability of the data for factor analysis, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was first conducted (see Appendix A for details). The results of Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value was 0.927, suggesting a high degree of sampling adequacy and confirming that the dataset was appropriate for factor analysis.

EFA was performed using principal component analysis as the extraction method, followed by Varimax orthogonal rotation to maintain the independence of factors while maximizing interpretability. All items loaded strongly on their intended factors, with factor loadings exceeding 0.60 and no significant cross-loadings, confirming the discriminant validity of the measurement structure.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2.1. Phase 1: Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the First-Order Factors

To validate the measurement model of the proposed first-order factors of service quality, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted. The results demonstrated a good model fit (χ2/df = 2.40, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.04), indicating that the measurement model was acceptable.

All standardized factor loadings (λ) for the first-order constructs were above the recommended threshold of 0.70, confirming strong item reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all constructs ranged from 0.815 to 0.877, suggesting high internal consistency. The composite reliability values exceeded 0.80 for all constructs, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values were greater than 0.50, demonstrating good convergent validity.

Specifically, the six first-order constructs—timeliness, physical facilities, ease of return, employees’ knowledge, flexibility, and responsiveness to delivery discrepancies were successfully validated and provided the basis for constructing the higher-order dimensions of high-tech and high-touch orientation service quality attributes in the next phase. The detailed results of the confirmatory factor analysis are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis results of the first-order factors.

4.2.2. Phase 2: Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Second-Order Structural Model

In the second phase, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted on the structural model by incorporating the second-order constructs. The model fit indices remained acceptable (χ2/df = 2.59, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05), further supporting the validity of the model. The detailed results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Confirmatory factor analysis results for the second-order structural model constructs.

The second-order construct of high-tech orientation was reflected in three dimensions: timeliness, physical facilities, and ease of return. Conversely, high-touch orientation comprised employees’ knowledge, flexibility, and responsiveness to delivery discrepancies.

The composite reliability (CR) values for all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, confirming the reliability of the measurement items. The standardized factor loadings were all greater than 0.70, and the average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded the 0.50 benchmark, demonstrating satisfactory convergent validity. Specifically, the CR and AVE values were 0.808 and 0.586 for high-tech orientation, 0.854 and 0.663 for high-touch orientation, and 0.801 and 0.574 for satisfaction. These results collectively confirm that the measurement model exhibits adequate reliability and convergent validity.

We also acknowledge that, given our relatively large sample size (N = 455), the chi-square statistic tends to be sensitive to trivial model misspecifications and therefore should not be interpreted as a sole indicator of fit. In line with best practices, we now emphasize multiple goodness-of-fit indices, including CFI, TLI, and SRMR, to provide a triangulated evaluation of model adequacy. The reported values (CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.05) all meet the recommended thresholds.

We performed a comprehensive model comparison including four alternative measurement structures: (1) three high-Tech related first-order factors, (2) three high-Touch related first-order factors, (3) six correlated first-order factors, and (4) the proposed second-order model. Model 4 achieved the best fit (χ2/df = 2.59, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05) and the lowest AIC and BIC values among the competing models (see Appendix B for details).

Therefore, the comparison among the four tested models indicates that our proposed model offers the best fit to the data. It demonstrates the most favourable combination of fit indices, with the lowest χ2/df, RMSEA, SRMR, AIC, and BIC values, and the highest CFI and TLI. Taken together, these results suggest that the proposed model provides an optimal balance between goodness of fit and model parsimony, confirming its suitability as the most appropriate representation of the underlying relationships in this study.

Furthermore, Harman’s single-factor test was performed to statistically examine the extent of CMV. All observed items were entered into an unrotated exploratory factor analysis to determine whether a single factor would account for the majority of the covariance among the measures. The analysis showed that the first factor explained 36.13% of the total variance, which is below the recommended 50% threshold. This result suggests that common method bias is unlikely to have a substantial effect on the study’s findings.

In addition, to assess potential multicollinearity among the constructs, Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) were calculated. All VIF values were below 3.0, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a concern and that the constructs were sufficiently independent for further analysis.

As shown in Table 6, the AVE values for high-tech (0.586), high-touch (0.663), and Satisfaction (0.574) are all greater than their corresponding squared correlations. This indicates that each construct is empirically distinct, and that discriminant validity is fully supported.

Table 6.

AVE values, correlations, and squared correlations of the constructs.

To further verify discriminant validity, the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratios were examined. The square roots of the AVE values for all constructs were greater than their inter-construct correlations. In addition, all HTMT ratios ranged between 0.692 and 0.781, remaining below the 0.85 threshold [70]. Please see Appendix C for details.

Appendix D presents the correlation matrix of all latent constructs. The correlations among constructs ranged from 0.541 to 0.603, all below the 0.80 benchmark. The diagonal elements represent the square roots of the AVE (0.765, 0.814, and 0.758), each greater than the off-diagonal correlations.

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

The SEM was used to examine the hypothesized relationships among the constructs. The results are shown in Table 7. H1, which proposed a positive relationship between high-tech orientation service quality and consumer satisfaction, was supported. The path coefficient was statistically significant and strong (β = 0.879, p < 0.001). H2, which posited a positive relationship between high-touch orientation service quality and consumer satisfaction, was also supported (β = 0.808, p < 0.001).

Table 7.

Results of hypothesis testing.

To further test the robustness of the structural model, age, education, and use frequency of omni-channel retailing were included as control variables. The extended model exhibited an acceptable fit (χ2/df = 2.59, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05). The results indicate that age (β = 0.009, p = 0.83) and education (β = 0.014, p = 0.73) had no significant effects on satisfaction, whereas use frequency of omni-channel retailing had a significant positive effect (β = 0.109, p < 0.01). Importantly, the inclusion of these control variables did not change the direction or significance of the main hypothesized paths. High-tech orientation (β = 0.866, p < 0.001) and high-touch orientation (β = 0.816, p < 0.001) remained strong and significant predictors of consumer satisfaction, confirming the stability and robustness of the proposed model.

The standardized path coefficients, together with standard errors, t-values, and 95% confidence intervals are reported in Table 8. All paths were statistically significant at p < 0.001, confirming the robustness of the measurement model.

Table 8.

Standardized Path Coefficients, Standard Errors, t-values, and 95% Confidence Intervals.

To examine whether these two orientations differ significantly in their influence on satisfaction, an equality-constraint chi-square difference test (Δχ2) was conducted. The unconstrained model produced χ2 = 486.987 (df = 174), whereas the constrained model (βhigh-tech = βhigh-touch) yielded χ2 = 467.228 (df = 173). The chi-square difference was Δχ2 = 19.759 (p < 0.001). This result demonstrates that the impact of high-tech orientation on consumer satisfaction is significantly stronger than that of high-touch orientation, suggesting that high-tech orientation in logistics quality plays a more dominant role in shaping consumer satisfaction in the omni-channel context. The detailed results are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Chi-square Difference Test Results for Path Comparison.

4.4. Discussion

A noteworthy finding of this study is that both high-tech and high-touch orientations in logistics service quality play a significant role in improving consumer satisfaction, but the effect of high-tech orientation is statistically stronger. In this digital environment, consumers increasingly depend on advanced logistics technologies for real-time tracking, accurate delivery, and seamless coordination across multiple channels [71]. The relatively weaker effect of high-touch orientation indicates that human interaction remains an essential complementary factor. Consumers still expect logistics services to convey empathy, trust, and personalized care beyond functional efficiency. This finding expands the concept of empathy in the SERVQUAL framework by emphasizing its relevance in omni-channel logistics [72]. Ensuring emotional care for consumers can be achieved by training employees in communication skills, emergency response, and personalized service capabilities, which may have novel implications for practical applications.

The stronger effect of a high-tech orientation may be partly due to the demographic characteristics of the sample, sample is primarily composed of young, digitally literate consumers. According to digital native theory, the younger generation is digital native, having been exposed to and using digital technology from an early age [73]. Younger generation may be more reliant on technological solutions such as real-time tracking, automated warehousing, and streamlined returns. This group values efficiency, transparency, and control, which may explain why high-tech orientation exerts a greater influence on satisfaction.

The significant contribution of a high-touch orientation means that technology alone cannot fully maximize consumer satisfaction. Due to the significant increase in disposable income among young people in Shanghai, China, driven by economic development [74]. This allows them to make more choices in their consumption, enjoy personalized products and services, and be willing to pay a premium for quality, service, and experience. This research result highlights that the impact of different age groups on satisfaction with logistics services in human–computer interaction or human–human interaction in omni-channel retailing deserves further attention from researchers.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study provides theoretical contributions in the following areas. First, this study improves the SERVQUAL model [35] to make it applicable to omni-channel retail scenarios, thereby promoting the development of logistics service quality theory. The traditional SERVQUAL framework includes five evaluation dimensions: tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [30]. Based on the relevant literature on omni-channel logistics [33,34,35,36], this study divides these five dimensions into the technical attributes and interpersonal interaction characteristics of logistics services [36], and adds a flexibility dimension to measure the ability of retailers to meet differentiated consumer needs through diversified distribution and return solutions. This expansion enables the model to more completely cover various logistics links such as purchase, exchange, and return. By integrating these elements, this study enhances the explanatory power of the SERVQUAL model in the omni-channel scenario, making the analysis of the impact of consumer satisfaction more systematic than the scattered attribute factors usually examined.

Secondly, the study proposes an innovative, integrated research methodology, combining the SERVQUAL framework, self-determination theory, and social presence theory. This validates the applicability of self-determination theory and social presence theory to the logistics industry, applying a sociological perspective to LSQ to explain how logistics consumers maintain and build social relationships through their consumption practices, and further explores consumer logistics needs within the omnichannel retail environment. Research on satisfaction with different dimensions of logistics service quality in omnichannel retail is limited. Drawing on insights from the SERVQUAL framework, self-determination theory, and social presence theory, this study reveals that both high-tech and high-touch aspects of logistics service quality play a significant role in enhancing consumer satisfaction.

Lastly, this study enriches theoretical understanding of the relationship between service quality and satisfaction in omni-channel retailing. Previous studies on the specific context of omni-channel retailing logistics have primarily focused on identifying the impact of omni-channel retailing logistics service attributes on consumer satisfaction [30,75,76]. This paper utilizes high-tech and high-touch approaches to summarize complex intervaried relationships, thus more accurately revealing how logistics service quality influences consumer satisfaction through both human–computer interaction and human-person interaction. Ultimately, the effect of high-tech approaches is slightly stronger, expanding existing knowledge. This study confirms the shift in consumer expectations, with logistics services transcending traditional social habits and demands, closing the loop on consumer independence and personal space. This outcome can also be explained by self-determination theory. When consumers prefer self-service or interaction with the system rather than relying on manual services, they hope to make independent decisions and proceed at their own pace without interference from others, which enhances the intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy of the decision-making process [77].

5.2. Managerial Implications

A high-tech service orientation enables technological and digital transformation in logistics. Through the integration of front-end consumer touchpoints based on human–computer interaction, consumers are empowered to communicate with service robots, place orders, check delivery status, and manage pick-up or return processes independently, which can enhance their sense of self-control. In practice, retailers can also redesign distribution networks to deliver directly to consumers and stores, ensuring product availability, accommodating diverse delivery times, and facilitating convenient returns [63]. High-tech systems further allow for flexible responses to shifting consumer demands, which can accelerate inventory management and order processing. The application of technologies such as RFID, drones, and automated sorting enhances physical facilities, timeliness, and ease of return, then the overall efficiency and reliability of logistics services can be improved [24]. In turn, efficient, accurate, and seamless service experiences significantly raise consumer satisfaction, aligning with modern consumers’ expectations [21]. At the same time, according to self-determination theory, human–computer interaction meets the psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. LSQ needs to consider consumers’ demand for making decisions at their own pace, mastering the use of technology, and experiencing a sense of belonging from human–computer interaction.

In contrast, a high-touch service orientation emphasizes interpersonal interactions and personalized experiences. Given that consumers often form stronger impressions through direct interactions, attributes such as staff expertise, flexibility, and responsiveness to delivery discrepancies play a vital role in strengthening consumer identification with logistics services. Emotional connections and trust can be fostered by training employees in communication, emergency handling and personalized problem-solving. Similarly, the professionalism of delivery personnel must be improved and the expertise of in-store staff during pickup or returns must be enhanced, as this contributes to consumer satisfaction [14]. According to social presence theory, these interpersonal interactions can meet consumers’ needs for immediacy, multiple cues, and personalization. High-touch LSQ service needs to allow direct and rapid problem resolution, use multiple senses, and experience emotions and attitudes through interpersonal interactions, which help to alleviate loneliness and create a sense of care and appreciation among consumers [78].

Finally, retailers should rationally balance technological and human resources based on the characteristics of their target consumers. Consumer preferences, expectations and interaction habits can be understood through follow-up surveys, focus groups and analysis of historical transaction data. Monitoring consumer feedback on social media further enables the identification of emerging service needs and interaction trends. Retailers can then segment consumers into distinct groups, track online comments and suggestions, and extract interaction preferences using data analytics. Retailers can refine both human–computer and interpersonal interactions by establishing dedicated online platforms and encouraging consumers to share feedback. Purposefully training employees alongside the integration of advanced technologies ensures that logistics services remain adaptive, personalized, and consumer-centred.

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

With regard to limitations and future improvements, first, the sample was limited to respondents from Shanghai, and the age distribution was concentrated between 19 and 40 years. Although this pattern aligns with the demographic structure of active omni-channel users in urban China, it may restrict the generalizability of the results. Future studies could include more diverse samples across regions, socioeconomic groups, and age cohorts to further test the robustness and external validity of the high-tech and high-touch frameworks in different cultural and market contexts. Second, this study used cross-sectional data and cannot capture the long-term impact of changes in service quality on consumer satisfaction. Future research could use longitudinal data to explore the long-term impact of the two types of service quality on consumer loyalty and repurchase behaviour.

With regard to future research directions, first, self-determination theory and social presence theory exhibit significant differences across cultures and contexts. Cultural transmission methods, the influence of power distance, and differences in interaction styles all influence the theoretical performance. Therefore, these two theories can be applied across diverse cultural contexts to explain how logistics consumers maintain and build social relationships through their consumption practices. Secondly, the importance of human–machine interaction and interpersonal interaction in logistics services can be explored in more niche areas, such as cold chain logistics and food delivery logistics. Furthermore, because both technology and human labour require costs, the mediating role of technology usage and interpersonal interaction costs in the relationship between customer satisfaction and the optimal balance of human–machine collaboration can be further explored. Finally, the concept of high-tech or high-touch driving customer satisfaction can be redefined from the perspective of humanoid service robots.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.X., J.X. and L.C.; methodology, D.X.; software, D.X.; validation, D.X. and X.W.; formal analysis, D.X. and L.C.; investigation, D.X. and J.X.; resources, D.X. and L.C.; data curation, D.X. and L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.X. and J.X.; writing—review and editing, L.C., X.W. and P.-L.L.; visualization, X.W. and P.-L.L.; supervision, X.W. and P.-L.L.; project administration, X.W. and P.-L.L.; funding acquisition, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Chung-Ang University Research Scholarship Grants in 2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was exempted from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review under the criteria of the Ethics Committee of Chung-Ang University, which specify that IRB approval is not required for research that does not collect or record personally identifiable information, does not directly identify participants, and does not involve sensitive information as defined in Article 23 of the Personal Information Protection Act. Our study falls within this category and therefore does not require formal IRB approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Items | TIM | PHY | EAS | EMP | FLE | RES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIM1 | 0.80 | |||||

| TIM2 | 0.85 | |||||

| TIM3 | 0.76 | |||||

| PHY1 | 0.72 | |||||

| PHY2 | 0.75 | |||||

| PHY3 | 0.83 | |||||

| EAS1 | 0.73 | |||||

| EAS2 | 0.78 | |||||

| EAS3 | 0.70 | |||||

| EMP1 | 0.71 | |||||

| EMP2 | 0.85 | |||||

| EMP3 | 0.79 | |||||

| FLE1 | 0.74 | |||||

| FLE2 | 0.81 | |||||

| FLE3 | 0.76 | |||||

| RES1 | 0.73 | |||||

| RES2 | 0.75 | |||||

| RES3 | 0.72 |

Exploratory factor analysis results.

Appendix B

| Model | Description | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Three high-tech related factors (TIM, PHY, EAS) | 4.72 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.082 | 0.071 | 24,015 | 24,300 |

| Model 2 | Three high-touch related factors (EMP, FLE, RES) | 4.46 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.079 | 0.067 | 23,920 | 24,250 |

| Model 3 | Six correlated first-order factors | 2.70 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.060 | 0.056 | 23,685 | 24,020 |

| Model 4 | Two-factor hierarchical model (high-tech and high-touch) | 2.59 | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.058 | 0.050 | 23,570 | 23,880 |

Comprehensive model comparison.

Appendix C

| Construct | High-Tech | High-Touch | Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-tech | 1.000 | 0.781 | 0.692 |

| High-touch | 0.781 | 1.000 | 0.734 |

| Satisfaction | 0.692 | 0.734 | 1.000 |

HTMT Ratios for Discriminant Validity.

Appendix D

| Construct | High-Tech | High-Touch | Satisfaction | √AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-tech | 0.765 | 0.765 | ||

| High-touch | 0.541 | 0.814 | 0.814 | |

| Satisfaction | 0.574 | 0.603 | 0.758 | 0.758 |

Correlation Matrix with √AVE.

References

- Faria, S.; Carvalho, J.M. From a Multichannel to an Optichannel Strategy in Retail. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldivia, M.; Chowdhury, S. Adapting Business Models in the Age of Omnichannel Transformation: Evidence from the Small Retail Businesses in Australia. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, I.D.; Dabija, D.-C.; Cramarenco, R.E.; Burcă-Voicu, M.I. The Use of Digital Channels in Omni-Channel Retail—An Empirical Study. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, O.; Karjaluoto, H.; Saarijärvi, H. Personalization and Hedonic Motivation in Creating Customer Experiences and Loyalty in Omnichannel Retail. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melacini, M.; Perotti, S.; Rasini, M.; Tappia, E. E-Fulfilment and Distribution in Omni-Channel Retailing: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 391–414. [Google Scholar]

- Asante, I.O.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, X. Leveraging Online Omnichannel Commerce to Enhance Consumer Engagement in the Digital Transformation Era. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Majer, M.; Kim, H.-J. Empirical Study of Omnichannel Purchasing Pattern with Real Customer Data from Health and Lifestyle Company. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.F.; Alanadoly, A.B. Driving Customer Engagement and Citizenship Behaviour in Omnichannel Retailing: Evidence from the Fashion Sector. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2024, 28, 98–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harter, A.; Stich, L.; Spann, M. The Effect of Delivery Time on Repurchase Behavior in Quick Commerce. J. Serv. Res. 2025, 28, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D.; Chen, T.; Yuen, K.F. Consumer Logistics in Contemporary Shopping: A Synthesised Review. Transp. Rev. 2023, 43, 502–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameen, N.; Tarhini, A.; Shah, M.; Madichie, N.O. Going with the Flow: Smart Shopping Malls and Omnichannel Retailing. J. Serv. Mark. 2020, 35, 325–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghiri, S.; Mirzabeiki, V. Omni-Channel Integration: The Matter of Information and Digital Technology. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 1660–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, J. Will Marketing Automation Encourage Repurchase Intention Through Enhancing Brand Experience? An Empirical Study of Omni-Channel Retailing in China. In Marketing and Smart Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, H. Unraveling How Poor Logistics Service Quality of Cross-Border E-Commerce Influences Customer Complaints Based on Text Mining and Association Analysis. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restuputri, D.P.; Indriani, T.R.; Masudin, I. The Effect of Logistic Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty Using Kansei Engineering during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1906492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, D.A.; Rasheed, D.R. Logistics Service Quality and Product Satisfaction in E-Commerce. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440231224250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Mamun, A.A.; Yang, Q.; Masukujjaman, M. Examining the Effect of Logistics Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction and Re-Use Intention. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinaddis, S.G.; Taye, B.A.; Yirsaw, B.G. Examining the Effect of Electronic Banking Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty: An Implication for Technological Innovation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Shi, X.; Song, G.; Huq, F.A. Linking Digitalization and Human Capital to Shape Supply Chain Integration in Omni-Channel Retailing. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2021, 121, 2298–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, E.H.; Sgarbossa, F.; Berlin, C.; Neumann, W.P. Human-Centric Production and Logistics System Design and Management: Transitioning from Industry 4.0 to Industry 5.0. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 7749–7759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Kannan, P.K.; Inman, J.J. From Multi-Channel Retailing to Omni-Channel Retailing: Introduction to the Special Issue on Multi-Channel Retailing. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ren, C.; Wang, G.A.; He, Z. The Impact of Channel Integration on Consumer Responses in Omni-Channel Retailing: The Mediating Effect of Consumer Empowerment. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 28, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhong, R.Y.; Huang, G.Q. E-Commerce Logistics in Supply Chain Management: Practice Perspective. Procedia CIRP 2016, 52, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkha, H.; Khiat, A.; Bahnasse, A.; Ouajji, H. The Rising Trends of Smart E-Commerce Logistics. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 33839–33857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahalimoghadam, M.; Thompson, R.G.; Rajabifard, A. Determining the Number and Location of Micro-Consolidation Centres as a Solution to Growing e-Commerce Demand. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 117, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şişman, G.; Orel, F.D. The Impact of E-Commerce Supply Chain Agility and Logistics Service Quality on Repurchase Intention in a Business-to-Consumer Context: Evidence from an Emerging Market. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2025, 36, 1301–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risberg, A. A Systematic Literature Review on E-Commerce Logistics: Towards an e-Commerce and Omni-Channel Decision Framework. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2023, 33, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumrit, D.; Sowijit, K. Winning Customer Satisfaction toward Omnichannel Logistics Service Quality Based on an Integrated Importance-Performance Analysis and Three-Factor Theory: Insight from Thailand. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2023, 28, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawa, A.; Światowiec-Szczepańska, J. Logistics as a Value in E-Commerce and Its Influence on Satisfaction in Industries: A Multilevel Analysis. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 36, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Liu, Y.; Po-Lin, L.; Zhu, X.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X. Assessing Logistics Service Quality in Omni-Channel Retailing Through Integrated SERVQUAL and Kano Model. Systems 2024, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murfield, M.; Boone, C.A.; Rutner, P.; Thomas, R. Investigating Logistics Service Quality in Omni-Channel Retailing. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2017, 47, 263–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, N.; Kilibarda, M.; Andrejić, M.; Jović, S. Satisfaction Is a Function of Users of Logistics Services in E-Commerce. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 33, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D.; Li, K.X.; Yuen, K.F. A Critical Assessment of Co-Creating Self-Collection Services in Last-Mile Logistics. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 846–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramarz, M.; Kmiecik, M. The Role of the Logistics Operator in the Network Coordination of Omni-Channels. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and Its Implications for Future Research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. A Service Quality Model and Its Marketing Implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J. Customer Orientation: Effects on Customer Service Perceptions and Outcome Behaviors. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.H.; Kim, T.Y.; Wang, X. Effects of Logistics Service Quality and Price Fairness on Customer Repurchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Cross-Border e-Commerce Experiences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-C.; Hsu, C.-L.; Lee, L.-H. Investigating Pharmaceutical Logistics Service Quality with Refined Kano’s Model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichhart, A.; Holweg, M. Creating the Customer—Responsive Supply Chain: A Reconciliation of Concepts. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2007, 27, 1144–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y.; Arsenovic, J.; Hellström, D.; Shams, P. Does Delivery Service Differentiation Matter? Comparing Rural to Urban e-Consumer Satisfaction and Retention. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, E.; De Grahl, A. The Flexibility of Logistics Service Providers and Its Impact on Customer Loyalty: An Empirical Study. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 47, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadłubek, M.; Thalassinos, E.; Noja, G.G.; Cristea, M. Logistics Customer Service and Sustainability-Focused Freight Transport Practices of Enterprises: Joint Influence of Organizational Competencies and Competitiveness. J. Green Econ. Low-Carbon Dev. 2022, 1, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masorgo, N.; Mir, S.; Hofer, A.R. You’re Driving Me Crazy! How Emotions Elicited by Negative Driver Behaviors Impact Customer Outcomes in Last Mile Delivery. J. Bus. Logist. 2023, 44, 666–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabelen, G.; Kaya, H.T. Assessment of Logistics Service Quality Dimensions: A Qualitative Approach. J. Shipp. Trade 2021, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Jackson, J.E. Investigating the Influential Factors of Return Channel Loyalty in Omni-Channel Retailing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 216, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumurtacı Hüseyinoğlu, I.Ö.; Sorkun, M.F.; Börühan, G. Revealing the Impact of Operational Logistics Service Quality on Omni-Channel Capability. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 1200–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkun, M.F.; Yumurtacı Hüseyinoğlu, I.Ö.; Börühan, G. Omni-Channel Capability and Customer Satisfaction: Mediating Roles of Flexibility and Operational Logistics Service Quality. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2020, 48, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.-I.; Woo, S.-H.; Kim, T.-W. Assessment of Logistics Service Quality Using the Kano Model in a Logistics-Triadic Relationship. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2017, 28, 680–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The General Causality Orientations Scale: Self-Determination in Personality. J. Res. Personal. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of Goal-Directed Behavior: Attitudes, Intentions, and Perceived Behavioral Control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Govindaluri, S.M. Omni-Channel Retailing in Supply Chains: A Systematic Literature Review. Benchmarking Int. J. 2021, 28, 2605–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A.; Holzapfel, A.; Kuhn, H. Distribution Systems in Omni-Channel Retailing. Bus. Res. 2016, 9, 255–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, S.G.; Navabakhsh, M.; Tohidi, H.; Mohammaditabar, D. A System Dynamics Model for Optimum Time, Profitability, and Customer Satisfaction in Omni-Channel Retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovezmyradov, B.; Kurata, H. Omnichannel Fulfillment and Item-Level RFID Tracking in Fashion Retailing. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 168, 108108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asawawibul, S.; Na-Nan, K.; Pinkajay, K.; Jaturat, N.; Kittichotsatsawat, Y.; Hu, B. The Influence of Cost on Customer Satisfaction in E-Commerce Logistics: Mediating Roles of Service Quality, Technology Usage, Transportation Time, and Production Condition. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J.; Williams, E.; Christie, B. The Social Psychology of Telecommunications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1976; ISBN 978-0-471-01581-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr, D.; Hassanein, K.; Head, M.; Ivanov, A. The Role of Social Presence in Establishing Loyalty in E-Service Environments. Interact. Comput. 2007, 19, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanpert, S.; Jacquemier-Paquin, L.; Claye-Puaux, S. The Role of Human Interaction in Complaint Handling. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Singh, R.K.; Koles, B. Consumer Decision-Making in Omnichannel Retailing: Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, C.A.M.; Young, A.W. Understanding Trait Impressions from Faces. Br. J. Psychol. 2022, 113, 1056–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liang, J. Concrete or Abstract: How Chatbot Response Styles Influence Customer Satisfaction. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 62, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risberg, A.; Jafari, H.; Sandberg, E. A Configurational Approach to Last Mile Logistics Practices and Omni-Channel Firm Characteristics for Competitive Advantage: A Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2023, 53, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Jonas, A. The Influence of E-Shopping Experience Factors on e-Consumer Satisfaction: Managing Online Stores. Retail Mark. Rev. 2024, 20, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos-Vallejo, C.A.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Cardona-Prada, J. Consumer Perceptions of Online Food Delivery Services: Examining the Impact of Food Biosafety Measures and Brand Image. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2023, 09721509231215739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Zhao, J.; Qi, G.; Kim, J.; Park, K. Online Retailer Cold Chain Physical Distribution Service Quality and Consumers: Evidence from China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2023, 26, 442–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savastano, M.; Anagnoste, S.; Biclesanu, I.; Amendola, C. The Impact of E-Commerce Platforms’ Quality on Customer Satisfaction and Repurchase Intention in Post COVID-19 Settings. TQM J. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.H.; Lu, C.S.; Yu, Y.H. Service Quality, Relationship Quality, e-Service Quality, and Customer Loyalty in the Container Shipping Service Context: A Moderated Mediation Model. Int. J. Shipp. Transp. Logist. 2024, 18, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, T.; Ellram, L.M.; Tate, W.L. A Note on the Use of Survey Research Firms to Enable Empirical Data Collection. J. Bus. Logist. 2015, 36, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 5th ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 978-1-4625-5191-0. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Cai, L.; Liu, Y.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X. From a Functional Service to an Emotional ‘Saviour’: A Structural Analysis of Logistics Values for in-Home Consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Yuen, K.F.; Fang, M.; Wang, X. A Literature Review on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Consumer Behaviour: Implications for Consumer-Centric Logistics. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 2682–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E.J.; Eynon, R. Digital Natives: Where Is the Evidence? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 36, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbab, P.; Sedighi, M. Comparison between the Old and New Generations of New Towns in China (Case Study: Shanghai Metropolitan Area). Q. J. Dev. Strategy (RAHBORD-E-TOSEEH) 2021, 17, 124–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer, J.T.; Flint, D.J.; Kent, J.L. Developing a Logistics Service Quality Scale. J. Bus. Logist. 1999, 20, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Cotarelo, M.; Calderón, H.; Fayos, T. A Further Approach in Omnichannel LSQ, Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2021, 49, 1133–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-T.H.; Nguyen, D.M. Service Failure and Self-Recovery in Tech-Based Services: Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 1075–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrum, L.J.; Fumagalli, E.; Lowrey, T.M. Coping with Loneliness through Consumption. J. Consum. Psychol. 2023, 33, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).