Abstract

Service platform enterprises have become a prominent economic form in China’s digital economy in the past two decades. The scope of complementary assets is expanding; for example, big data, precision marketing and user traffic conversion are among the emerging manifestations of complementary assets. Nevertheless, scholars have not yet explored how service platform enterprises utilize and maintain these vast complementary assets in the dynamic environment. Building on value innovation theory, this article attempts to reveal the impacts of complementary assets on the value innovation of service platform enterprises, and the conditioning roles of environmental dynamics. By contrasting findings and theoretical replication, we find that (1) complementary assets (specialized complementary assets, universal complementary assets) have promoting effects on service platform enterprises’ value innovation (customer value, partnership, business model changes); (2) environmental dynamics (market changes, technological changes) have moderating effects on the relationship between complementary assets and the value innovation of service platform enterprise. This research provides a novel and fine-grained theoretical framework to illustrate the multidimensional impacts of complementary assets and the contingent roles of a two-dimensional environmental dynamics on value innovation, thereby enriching the literature on value innovation theory and complementary assets, and providing actionable insights for service platform enterprises in leveraging complementary assets for value innovation, as well as guidance for regulatory departments in digital governance.

1. Introduction

Over the past few years, digital technology advances have boosted the platform economy (the reorientation of businesses around digital platforms that enable interactions between consumers and producers [1]), creating many internet platforms and transforming innovation approaches [1,2,3,4]. As digital platforms compete yet increasingly converge, complementary assets and complementary technologies are more important than ever [5].

Complementary assets refer to other assets, resources, or capabilities that are needed to enhance the value of core products or technologies beyond them [5,6]. Enterprises need to utilize existing technology and resources to function and obtain profits in a dynamic environment [7]. China’s large user base and innovative business models have made it a global leader in digital offices, mobile social networking, and payment. The platform economy, accompanied by mobile payments and remote work, has generated a large number of users and office data, creating a huge database and bringing numerous complementary assets to enterprises. As products become increasingly commercialized, marketers need to address the personal and more subjective value factors in purchasing [8].

As a key determinant of organizational success [9], value innovation positively impacts operational marketing capabilities, which in turn enhances organizational outcomes [10]. Value innovation has been widely applied in business innovation, education, non-profit organizations and other sectors [11,12,13,14], but research on its adaptability in the service platform enterprise remains insufficient. Since research on value innovation usually examines its significance and focuses on analyzing processes, there is relatively little empirical research on value innovation, with most studies employing qualitative research methods. The influencing factors of value innovation in existing research are relatively abundant but scattered, including market (the number of developers [15]), enterprise resources (digital assets [16], product sales), organizational factors (enterprise network structure, partnerships [17], enterprise experimental learning [18]), management factors (social responsibility and dynamic capabilities [19], learning ability [20]), and environment (national risk [21]). Platform enterprises’ success relies on complementary innovation [22]. However, in terms of enterprise resources, few researchers consider complementary assets as an antecedent variable of value innovation, which is an important variable in service platform enterprises that has already attracted the attention of a wide range of scholars in the era of the platform economy. In terms of the VRIN (valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, non-substitutable) principle emphasized by the resource-based view [23], complementary assets of platform enterprises perfectly fit the characteristics of being valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable. Therefore, based on resource-based theory, complementary assets should be regarded as important antecedent variables of platform enterprises’ value innovation in terms of enterprise resources for further exploration.

The contingency view posits that management strategies should adopt the most suitable management model, program, or methodologies based on the internal and external environments, and specific situations should be analyzed on a case-by-case basis. Environmental dynamics serve as a critical contingent factor that cannot be overlooked in entrepreneurship and innovation research [24]. As an exogenous contingency independent of the organization, the environment exerts lasting effects on organizations, requiring adaptive capabilities to respond to its dynamism. Therefore, deeply exploring the impact of complementary assets and environmental dynamics on the platform enterprises’ value innovation is necessary.

By exploring the relationship between complementary assets, value innovation, and environmental dynamics, the research questions are as follows: (1) What is the relationship between complementary assets (specialized complementary assets, universal complementary assets) and service platforms enterprises’ value innovation (customer value, partnership, business model changes)? (2) What are the differences in the impact of complementary assets on value innovation in different dynamic environments (market changes, technological changes)?

This paper makes three key contributions to research on complementary assets and platform enterprises’ value innovation: First, it enriches the existing value innovation and platform enterprises literature by exploring the gap between complementary assets and service platform enterprises’ value innovation. Second, using environmental dynamics as moderating variables between complementary assets and platform enterprises’ value innovation, both market changes and technological changes positively moderate the impact of complementary assets on service platform enterprises’ value innovation, which enriches the theory of value innovation. Third, an integrated framework of complementary assets, platform enterprises’ value innovation, and environmental dynamics is proposed by using a comparative dual case study to examine how leading platform enterprises leverage complementary assets to promote value innovation. This provides practical implications for platform enterprises to focus on and better utilize complementary assets for value innovation.

The paper’s remaining structure is as follows: (1) a literature review, identifying research shortcomings and raising questions; (2) research design and methodology; (3) case briefing, using BEKE and Trip.com Group as research objects; (4) findings, including open coding and axial coding; (5) discussion, proposing propositions by contrasting findings of two cases and theoretical replication; (6) conclusions, theoretical contributions, practical enlightenment, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Complementary Assets

Teece first proposed the definition of complementary assets in the PFI (Profiting from Innovation) model. He pointed out that compared to technological innovation, complementary assets are the supporting assets like manufacturing, marketing, and aftercare that are located downstream of technological innovation and required to achieve innovation value [6]. Taylor (2009) pointed out that complementary assets are existing organizational capabilities and assets associated with the commercialization of new technologies [25]. Hess and Rothaermal (2011) determined whether it is a complementary or alternative asset based on its strategic location in the value chain, and whether there is a substitution relationship between assets located in the same location [26]. When engaging with the platform ecosystem to pursue the many opportunities available, enterprises should strategically leverage the complementary resources and capabilities supplied by the platform ecosystem [4]. Helfat (2018) points out that platform enterprises rely more on complementary assets than traditional enterprises, such as products and services that complement platform enterprises, and complementary technologies (e.g., software) that facilitate the innovative commercialization of platform enterprises’ innovations [27]. A startup’s ability to access numerous complementary assets is quite critical [28].

The increase in complementary assets will enhance the value proposition for demand-side participants [29,30]. Rothaermel (2001) explored cooperation between platform enterprises and newly entered small businesses; he proposed that platform enterprises focused on exploring complementary assets had better business performance than those focused on investigating new technologies [31]. Matching complementary assets with dual learning dynamics will enhance innovation capabilities [32]. Complementary assets have a positive impact on the value innovation of platform enterprises [33].

2.2. Value Innovation

Kim and Mauborgne (1997) [34] first introduced the concept of value innovation in “Blue Ocean Strategy”. The authors conceptualized value innovation as changing the value proposition, delivering exceptional user value at low cost, and realizing the seemingly contradictory strategic synergy between low cost and differentiation [34]. Anderson (2006) [35] proposed that value innovation is mainly reflected in the form and combination of new elements that can create value for customers, partners, and internal employees, ultimately bringing significant value. Value innovation focuses on creating more valuable services and products unknown to competitors, discarding the competitive mindset [11]. Fan Jingming (2021) [36] summarized three characteristics of the connotation of value innovation: redividing the market, reidentifying customer needs, and rearranging organizational resources. Value innovation redefines business models, transforms markets, and serves customers better to create high value and business growth [37,38].

The main related areas of value innovation include strategy and management disciplines (29%); business, management and accounting (26%); management of technology and innovation (19%); and business and international management (16%). Although value innovation has marketing-related attributes, the proportion of published articles in marketing journals is extremely low (4%) [39].

Numerous studies establish value innovation as an independent or mediating variable, showing its determinative role in business innovation and organizational success. However, while the enterprises’ resources of the value innovation antecedent variable include source, production, and consumption factors, as well as digital assets [16], scholars have not focused on the growing wealth of complementary assets of platform enterprises.

2.3. Environmental Dynamics

The environment is an exogenous variable independent of the organization’s external environment, which can have a sustained, explicit, or potential impact on its operational performance. Environmental dynamics quantify the rate of changes in the environment the enterprise operates in; that is, the rate and degree of changes in environmental factors have different impacts on the enterprise [40]. Environmental dynamics are typically manifested in key areas spanning technological progress and changes, customer demand, and the behavior of competitors and suppliers [41]. Environmental dynamics contribute to the proactive impact of innovation ambidexterity on business performance [42].

With the increasing dynamics of the environment, enterprises need to integrate and restructure their organizational structure and processes to actively adapt to environmental changes [43]. When the environmental dynamics are low, the market demands and technological changes are easy to predict. When the environmental dynamics are high, the knowledge will quickly become outdated in market competition, rapidly changing technological activities and market demands. Organizational designs lose value when they cannot adapt to environmental changes [44].

2.4. Related Theory

Value innovation theory advocates that companies should open up blue oceans (new markets without competition) through value innovation, rather than fighting each other in red oceans (existing saturated markets) [34]. Strategic management has traditionally emphasized competitive advantage as the central paradigm for understanding enterprise competitiveness, wrongly believing that the focus of the strategy is to defeat competitors. However, if you ignore the needs of the customer and cannot create greater value for the customer, then any competitive behavior between enterprises is a meaningless internal consumption. The biggest limitation of the Blue Ocean Strategy lies in Kim’s neglect of the differences between enterprises in the existing competition, blindly believing that there is a high degree of homogenization between enterprises [45,46]. However, the key to whether an enterprise can occupy a dominant position in the market and achieve high profits lies in the accurate identification, effective construction, continuous maintenance, and rational utilization of its core resources and capabilities. Value innovation theory breaks through the boundaries of “platform-industry” and overcomes the limitations of platforms that often focus on a single industry. It integrates value across industries, such as Meituan expanding from food delivery to instant retail, reusing its delivery network and merchant resources, and transforming its “delivery” capabilities into complementary assets across industries [33]. Complementary assets can enhance the value proposition of a platform and help platform companies explore new markets. The “ERRC framework” (eliminate, reduce, raise, create) of value innovation theory can be used to optimize the combination of complementary assets [6,47]. Therefore, this paper is based on the value innovation theory.

Dynamic capability theory is also commonly used in the analysis of platform enterprise innovation. Dynamic capability theory seeks to explain how organizational strategies and resource elements can effectively support companies in building and maintaining significant competitive advantages in dynamic environments [47]. Dynamic theory emphasizes that companies need to closely monitor market and environmental changes, as well as the actions of competitors, and convert identified business opportunities into actual business to achieve commercial value enhancement [48]. Dynamic theory often relies on case studies, but the experiences of successful enterprises may not be replicable (unique historical backgrounds, leadership, or luck factors) [49], and there may be a survivorship bias: the dynamic capability deficiencies of failed enterprises are less deeply explored.

In summary, previous studies have promoted understanding of the antecedents of value innovation and its patterns of action: (1) Existing studies have examined complementary assets in traditional enterprises, yet overlooked their critical role in platform enterprises’ value innovation; value innovation theory does not sufficiently consider resource heterogeneity. This paper takes into account the heterogeneity of enterprises’ resources and explores the impact of complementary assets, an important resource for value innovation, to fill the gap. (2) Current literature neither sufficiently explores the relationship between complementary assets, environmental dynamics, and value innovation, nor adequately addresses how dynamic environments moderate platform enterprises’ complementary assets. This paper uses richer case material to explore the correlation of complementary assets in value innovation from the perspective of platform enterprises in dynamic environments. Therefore, it is necessary to reveal the novel theoretical framework of the impact of complementary assets and environmental dynamics on the platform enterprises’ value innovation based on value innovation theory and resource-based theory.

3. Research Design and Methodology

3.1. Research Method

This article adopts a dual case study method, constructing a new theoretical framework through the analysis and comparison of two case materials. The reasons are as follows:

- (1)

- The case study method is a qualitative research approach, widely employed to investigate a specific complex phenomenon or problem through systematic generalization and theoretical refinement of single or multiple cases. Based on the context of China’s new platform economy, the pioneering research addresses a knowledge gap through case-based theory development. Insights into first-hand data from enterprises will enable us to better understand specific events, underlying processes, operational mechanisms, and participant involvement across different activities [50]. Research questions (outlined in the introduction) all address the issues of “How” and “Why”; the nature of the research question determines case study methodology to elucidate the theoretical logic and patterns underlying complex phenomena [37].

- (2)

- The multi-case-study method enables the generalization and analysis of common patterns across multiple cases, offering richer empirical data, reduced bias, stronger credibility, and more robust theoretical development [51,52]. This approach yields findings with greater generalizability and theoretical rigor.

3.2. Case Selection

According to the research questions and research objectives of this research, the selection of case enterprises follows the following criteria: (1) platform enterprises that have already been established and are in continuous operation; (2) platform enterprises with a large number of complementary assets; (3) platform enterprises with successful value innovation behaviors; (4) platform enterprises whose business concepts are inspirational to other companies or industries; (5) platform enterprises that are in the midst of rapid changes in the market and technology.

The selection of cases should follow the principle of theoretical sampling [53,54]. The theoretical sampling is operationalized by starting with the collected BEKE, forming tentative ideas about the information, and testing these ideas through further empirical inquiry. The researcher generalizes an inference after the information about the BEKE has been collected and analyzed. This inference provides a possible theoretical explanation for BEKE. The researcher deduces a subsequent research hypothesis based on this theoretical explanation, returns to the empirical world to collect more case data to test this hypothesis and develop a more detailed theory, and chooses the Trip.com Group to conduct a comparative case study. For ease of understanding, Trip.com Group will be abbreviated as Trip in the following text.

To align with the research questions, two enterprises, Trip and BEKE, were selected for a dual case study.

The reasons for choosing these two platform enterprises are as follows:

- (1)

- Heterogeneity. The two service platform enterprises belong to different industries, and comparing them based on theoretical replication improves the universality of cross-case studies.

- (2)

- Representativeness. Trip holds the distinction of being the largest listed online ticketing service platform enterprise in China. After 24 years of development, it has the Trip Quest AI model (universal complementary assets) and Kun Panorama marketing platform (specialized complementary assets), including hotel reservations, transportation reservations, tourism vacation reservations, tourism strategies, tourism insurance, food shopping, car rental, foreign currency exchange, and other tourism-related services. The iteration of AI technology has also increased the level of partnership with its partners, with outstanding value innovation during the pandemic.

BEKE, formerly known as Lianjia, is a leading brand in the real estate intermediary industry. BEKE has evolved from a vertically integrated operator to an innovative digital open platform brand. BEKE owns the core data asset—the “Property Dictionary”—and Lianjia’s real property listing standard (specialized complementary assets), which increase its market value. It has also taken the lead in mass-producing VR-ized listing information (universal complementary assets). Through the rational use of complementary assets, BEKE has maintained significant competitiveness even in the midst of fast-changing markets and technologies and is a representative enterprise that meets the requirements of this study.

- (3)

- The availability of data. The data of key and important actors in Trip and BEKE can be readily sourced from official websites, prospectuses, annual reports, and other internal materials. Concurrently, the research team has been continuously tracking and researching the enterprise samples, amassing a substantial repository of primary case data through ongoing fieldwork.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

This study involved two coders.

Informed Consent: Clearly and concisely explain the study’s objectives and significance to participants. Detail what participants will be required to carry out (e.g., interview duration, frequency, observation content, recording status). Explicitly state how their data will be protected and describe specific anonymization methods. Inform participants that participation is entirely voluntary, that they have the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty, and that they will not face any adverse consequences for doing so.

Anonymization: Remove unnecessary sensitive information (e.g., phone numbers, email addresses, physical addresses). Replace real names and job titles with coded identifiers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of data sources.

The research follows these standards to improve reliability and validity: (1) Employing methodological triangulation, multiple channels are used to access different raw data to improve the reliability and validity of the data. (2) A meticulous case study plan is drawn up, and a comprehensive case study database is constructed through the collection of information from multiple systematic sources to facilitate subsequent testing and analyses at any time and to ensure reliability.

Triangulation is a research method that validates conclusions through multiple data sources and methods [55]. The use of triangulation enables a comprehensive understanding of the research problem, improves the credibility of the data, and enhances the reliability and rigor of the findings.

- (1)

- Field interview

The research team continued to focus on the operational dynamics of the case enterprises. We conducted semi-structured in-depth interviews with the headquarters and branch staff of the case enterprises, utilizing a hybrid approach combining on-site and virtual interview modalities. The interviewees included middle and senior management personnel, frontline business personnel, consumers, etc. Following each interview session, we immediately transcribed and systematically coded the recordings, while conducting iterative data verification through member checking to identify and address any informational gaps. They were sent via email or WeChat, or information was further enriched through phone calls or second meetings.

- (2)

- On-site observation

On-site observation refers to the researcher’s direct entry into the natural environment of the research object to observe, record, and collect data. The researcher went to BEKE physical stores, Trip physical stores, and consumer consumption environments to observe the decision-making basis of consumers and merchants in shopping, applying for cooperative merchants, etc. Meanwhile, the author also downloaded and used the apps and mini-programs of the two case companies, and paid attention to the public number, video number, jitterbug number, etc., so as to collect the data through observation.

- (3)

- Secondary data

The research utilizes secondary data collected from three main sources: internal data, public information, and research literature. The specific information of the data sources is detailed in Table 1.

In the process of collecting case materials, the time scope and geographical scope of the research topic and the cases were clarified, and the keywords of BEKE and Trip were searched in academic databases, case databases, search engines, government and institutional websites. Data directly related to the research theme were retained, and priority was given to data from authoritative organizations, well-known scholars, or high-quality journals and publishers to ensure the timeliness of the data. Data from multiple sources were used to form a single collection of case data; videos, audio, and images were converted into text suitable for analysis, and then coded according to the following rules: (1) coding for each case: BEKE coded as B, the Trip Group coded as X; (2) coding for the source of information: field interviews of customers coded as C, internal related information coded as ID, and so on, as shown in Table 1. Each piece of data was numbered according to the principle of “case name–source–serial number” and the alphabetic interpretation method, e.g., BC1 represents the first piece of BEKE’s field interviews of customers.

The coded data were categorized according to case name and chronological order, checked for completeness and consistency, and missing values, duplicated values, and erroneous information were deleted to form qualitative information. The organized raw data were imported into Nvivo 12.0 to assist coding. A random sample comprising 50% of Zuohui’s personal comments and interviews and 50% of BEKE’s video and audio interviews was selected. To ensure that the sample covered diverse data sources, two coders independently coded this overlapping portion. Their percent agreement reached 90%, meeting the acceptable threshold.

In the process of coding, firstly, we carried out intra-case analysis, identified the theoretical concepts and relationships related to complementary assets, value innovation, and environmental dynamics in the cases according to the analytical logic of “situation–behavior–result”, and established preliminary theoretical relationships. Then, following the replication, the new concepts, patterns, and interrelationships extracted from the coding process of individual cases were compared and verified with other cases to verify their universality and reliability, and to form theoretical concepts and relationships with more explanatory power and theoretical value. Subsequently, the coding results and the organizing process were repeatedly compared, adjusted, and corrected, and other researchers, experts, and relevant employees of the cases were invited to verify the coding results.

4. Case Briefing

4.1. Case A: BEKE

Founded in 2017, BEKE has strategically positioned itself as a technology-enabled premium residential service platform. BEKE provides total residential services, including new house transactions, second-hand house transactions, leasing, mortgage services, fund custody, and decoration design. The predecessor of BEKE is a leading brand chain in the real estate intermediary industry. BEKE is an innovative brand that has transformed from a vertical, self-supporting brand to a digital open platform. With verified property listings, strong professional ability, and a team of brokers with professional ethics, BEKE has become a listed company with the highest market share and a representative enterprise of the real estate service platform. In support of national digital transformation efforts (the use of new digital technologies to enable major business improvements [56]), China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) initiated the “Digital Transformation Partnership Action” program to accelerate the development of digital enterprises and ecosystems. BEKE participated in this initiative as a recognized industry-leading platform company. In July 2022, BEKE’s proprietary DevOps tool won the “excellent level” standard certification of the Institute of Information Technology. The characteristics of BEKE are mainly reflected in the Real Estate Dictionary function, the featured VR house viewing function, and the ACN broker cooperation mode based on the massive real estate sources accumulated by Lianjia for many years.

4.2. Case B: Trip.com Group

Headquartered in Shanghai since 1999, Trip is the largest online ticketing service platform enterprise in China. After 26 years, Trip now owns the Trip Asks AI model and the Kun panoramic marketing platform, including transport ticketing, hotels and accommodation, travel and holidays, attraction tickets, travel insurance, visa services, food recommendations, and other related services. It is at the forefront of national hotel reservation services. Trip leverages its operational scale, technological innovation, and sophisticated management systems to maintain competitive advantages across six key dimensions: technology platform, user experience, products and services, brand influence, market share, big data, and intelligence. These advantages enable Trip to maintain a dominant competitive position in the fierce market competition.

5. Findings

5.1. Open Coding

Before coding, we cleaned up any grammatically incorrect sentences or repetitive phrases. During the open coding process, we processed the data sentence by sentence, requiring coders to use the original sentences, refrain from imposing personal preferences, and work independently without influencing each other. After coding, we compared and discussed the coding results, merged concepts or categories with the same meaning, and consulted experts to modify or delete any ambiguous parts.

5.1.1. Open Coding of Complementary Assets

Helfat (1997) refers to assets that help companies commercialize innovation achievements as complementary assets [57]. According to the degree of dependence on innovative technology, complementary assets are usually divided into two categories: universal complementary assets and specialized complementary assets. Universal complementary assets do not rely on innovation and can be obtained through purchase; there is a unidirectional dependence between specialized complementary assets and innovation. The unidirectional dependence of assets on innovation is mainly reflected in the fact that relevant resources and capabilities are only applicable to this type of innovative product. The unidirectional dependence of innovation on assets is reflected in the dependence on relevant resources and capabilities to ensure the success of innovation [58].

The real housing resources of BEKE and the upstream and downstream sticky users of Trip are specialized complementary assets, while the VR and AI viewing functions of BEKE and Trip’s one-stop service platform are universal complementary assets. The specific primary and secondary code descriptions and corresponding case summaries of complementary assets are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of complementary assets in the case study.

5.1.2. Open Coding of Value Innovation

Existing research on value innovation mainly focuses on two perspectives: enterprises and customers. The enterprise perspective mainly focuses on its capabilities, costs, and performance, while the customer perspective mainly focuses on purchase intention and customer value. For example, Berghman [59] divided value innovation into customer value, business model, and partnership; Hao Bin [60] divided value innovation into enterprise performance, product value, and innovation capability.

The successful purchase of a new house by customers on the innovation activity launched by BEKE and the positive feedback from Trip customers on the refund policy during the epidemic period all belong to customer value. BEKE’s win–win partnerships with Country Garden and Sunac and TripAdvisor content being made available to Trip are manifestations of partnership in value innovation. The strategic innovations in BEKE and other related areas, along with the expansion of Trip, are manifestations of business model changes in value innovation. The specific primary and secondary code descriptions, along with their corresponding case summaries of value innovation, are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Description of value innovation in the case study.

5.1.3. Open Coding of Environmental Dynamics

The dynamic nature of the environment is typically reflected in technological advancements and changes, customer needs, and the behavior of competitors and suppliers [29]. The dimensions of environmental dynamics in existing research are mainly manifested through technological changes and market changes. Technological changes refer to the rate of change in the technological environment in which an enterprise is located, which is mainly caused by technological progress and change; market changes refer to the uncertainty in the market environment resulting from the instability and fluctuations in customer demand.

The transaction process digitization of BEKE and the rapid iteration of Trip’s tourism AI technology both exemplify technological changes; the change in homebuyer demand in BEKE, the real estate support policies, and the transformation of consumer demand in Trip all exemplify market changes. These are all reflections of the degree of market changes and technological changes in environmental dynamics. The specific first-level and second-level code descriptions, along with corresponding cases of environmental dynamics, are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Description of environmental dynamics in the case study.

5.2. Axial Coding

After open coding generates categorized concepts, axial coding analyzes open coding results by identifying causal/conditional relationships. The seven constructs (specialized complementary assets, universal complementary assets, customer value, partnership, business model changes, market changes, technological changes) generated by the secondary encoding are summarized into three main categories (complementary assets, value innovation, environmental dynamics). The results of axial coding are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Axial coding results.

5.3. Theoretical Saturation Test

Theory saturation is employed to assess whether the study has achieved saturation in the developed theory. This occurs when the new data can no longer provide new categories, attributes, or relationships through data analysis. At this point, the theory is sufficiently complete, and data collection and analysis can be stopped. We conducted theoretical saturation testing by reserving the last 10% of the data for validation. No new categories or properties emerged in final data, confirming that saturation was achieved. In this paper, the data collected were tested for theory saturation several times, and the results are shown in Table 6. The table shows that no new concepts, categories, or relationship connotations were formed, and the existing theories were able to fully explain the theoretical research phenomena. Hence, the coding results of this paper are saturated with the above theoretical models constructed.

Table 6.

Representative examples of saturation testing codes.

6. Discussion

In the previous section, the research identified the emerging constructs through analysis of case data, applying both open coding and axial coding. The results are presented in Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. Subsequently, the research examines the interrelationships among these constructs through replication and comparison methods.

6.1. Matching Complementary Assets with Value Innovation

- (1)

- Before 2014, there were inconsistent pricing and misleading listings for the same house in the secondary housing market, which confused buyers when identifying genuine listings. The launch of BEKE in 2018 addressed this issue by reducing fraudulent listings and improving transaction efficiency. Since 2008, Lianjia has invested significant manpower and resources to develop a Real Estate Dictionary—a comprehensive property database (specialized complementary assets) that records detailed multidimensional information for each listing, including unit numbers, standardized floor plans, and surrounding amenities. BEKE’s property search inherits Lianjia’s core data assets—the Real Estate Dictionary and standardized property listing system. These complementary assets enable BEKE to maintain a property listing accuracy rate of nearly 95%. BEKE has further opened its industry-leading platform to partners (partnership), eliminating the competitiveness of fraudulent listings. Both homebuyers and brokers have demonstrated strong approval of BEKE’s property search services using its Real Estate Dictionary.

BEKE’s property search platform has gained industry recognition as an innovative solution, significantly enhancing its market value. After years of cross-departmental collaboration and dedicated effort, BEKE has developed critical complementary assets, substantially enhancing customer value innovation (customer value). Keeping its Real Estate Dictionary as a foundational service, BEKE charges platform partners. In 2023, BEKE’s emerging businesses and other segments—which include revenue from SaaS solutions provided to brand owners, brokers, developers, and others—generated a total transaction volume of USD 13.9 billion, marking a 12.9% year-over-year increase.

Customer value, partnership and business model changes belong to the conceptual dimension of value innovation.

Therefore, we propose the following:

Proposition 1.

Specialized complementary assets have promoting effects on the platform enterprises’ value innovation.

Based on the logic of theoretical replication, we apply Proposition 1 to Trip to verify its generalizability.

Trip prioritizes brand building and maintenance. The group’s CEO emphasized the following: “The tourism industry should assume greater responsibility for carbon reduction (specialized complementary assets). We aim to collaborate with more industry partners to provide sustainable travel products for millions of tourists (customer value) and collectively promote sustainable travel”. This demonstrates how Trip’s brand-building development enhances its customer value.

Therefore, Proposition 1 holds true in Case B as well. The conventional paradigm in strategic management literature maintains that proprietary complementary assets are exclusively owned by enterprises. However, in our case, cross-industry membership benefits are shared. If diamond members can match their membership status with hotel loyalty programs, collaborating with brands like Marriott and Hilton, then users can unlock premium benefits from hotel groups directly through their membership tier. Through platform rule design, Trip has enabled what were once closed proprietary resources to achieve cross-organizational liquidity, further driving value innovation for enterprises. This can be achieved when member information is permitted to be accessed.

- (2)

- BEKE led the mass production of VR-enabled property information by acquiring complementary assets through advanced VR technology purchases (universal complementary assets). In 2020, following the COVID-19 pandemic, BEKE led an innovative approach to property transactions by introducing VR viewings, VR showings, online subscriptions, and online refunds facilitated by highly competent brokers (business model changes), which has increased the rate of showings and signing of contracts. In the second quarter of 2020, BEKE initiated an average of approximately 159,000 VR viewings per day, compared to 11,000 viewings during the same period in 2019. As the pioneer in applying VR technology to real estate, BEKE gained significant recognition from customers (customer value), while simultaneously reducing property viewing costs. Using AI algorithms to deeply analyze customer needs, relying on a self-developed model and ‘dream home’ image model, BEKE launched the first AIGC home decoration design product ‘Sheniu’ to provide developers, owners, builders, and other partners with product positioning and product design to improve partnerships.

Therefore, we propose the following:

Proposition 2.

Universal complementary assets have promoting effects on the platform enterprises’ value innovation.

Based on the logic of theoretical replication, we validate Proposition 2 by applying it to Trip.

Trip focuses its technological investments on three key areas: artificial intelligence, big data, and cloud computing. The company has made significant commitments to product development and technological innovation (universal complementary assets). Trip offers a ‘one-stop’ customer service robot that enables users to complete the entire consultation process through a single interface. Operating across 39 countries and regions with 24 language options, Trip prioritizes customer-centric solutions to meet traveler needs (customer value), and Trip’s strategic deployment of advanced technologies further drives continuous innovation in customer value. Meanwhile, Trip’s panoramic marketing AI strategy platform ‘Kun’ has made the previously fragmented marketing processes complete and efficient (business model changes), significantly reducing marketing costs.

Therefore, Proposition 2 holds true in Case B as well. Traditional complementary assets are viewed as static resources, with companies gaining competitive advantages by controlling key assets [6]. However, in BEKE and Trip, complementary assets have been digitized, e.g., VR property viewing + property dictionary, digitizing offline property listings to form an industry-standard database, and combining dispersed complementary services such as flights, hotels, and transportation through algorithms; therefore, they can provide real-time, personalized packages (flight + hotel + airport transfer one-click booking). This is a typical example of the integration of traditional industries and digital platforms. The practices of BEKE and Trip demonstrate that the value innovation of platform companies does not solely depend on technology or traffic but also on the governance of complementary assets. This is achievable when mobile internet and smart devices are highly prevalent, and digital technology tools are widely adopted by users.

6.2. Matching the Impact of Environmental Dynamics and Complementary Assets on Value Innovation

- (1)

- During the epidemic period, BEKE officially launched a “VR Sales Department” (universal complementary assets) that covers multiple functions, including VR viewing, online subscription, no-reason check-out, and online refunds. This innovation has fundamentally transformed the traditional sales office model, shifting from passive storefront operations that relied on walk-in customers to proactive digital engagement. Property securing, subscriptions, and signing contracts can all be completed online, accelerating real estate digitization and significantly reducing transaction costs (value innovation). The BEKE Hangzhou platform achieved an 80% online contract signing rate, with a 98% tax payment rate via cloud services. By 2024, it had processed over 10,000 online property transfer transactions. Under pandemic prevention and control measures (market changes), BEKE’s VR viewing capability has accelerated the promotion of the product value.

Market changes and technological changes are conceptual dimensions of environmental dynamism.

Therefore, we propose the following:

Proposition 3.

Environmental dynamics play a moderating role in the impact of universal complementary assets on value innovation.

Based on the logic of theoretical replication, we validate Proposition 3 by applying it to the Trip case.

During the pandemic, instant messaging system technology has undergone rapid changes (environmental dynamics), significantly enhancing Trip’s overseas brand products and services. Trip now delivers multilingual (20 languages) and multi-currency (31 currencies) support worldwide, while its Tianxun search engine (universal complementary assets) extends this capability to over 30 languages across 52 markets, boosting international service value (value innovation).

Therefore, Proposition 3 holds true in Case B as well. Dynamic environments have become triggers for value innovation. During the stagnation period of outbound travel, Trip launched the “Local Playmates” content community, transforming travel influencer resources into a local lifestyle recommendation engine and opening up new advertising revenue streams. In highly dynamic environments, specialized complementary assets may exhibit multi-utility, promoting disruptive innovation [61]. This can be achieved when the platform possesses robust organizational coordination strength, enabling effective integration of diverse assets (outbound travel support services and local lifestyle support services) while avoiding internal conflicts.

- (2)

- To meet changing housing market demands (market changes), BEKE analyzes existing users and understands user attributes. For example, users who read encyclopedia articles related to purchase restrictions or loans and track market fluctuations are more likely to buy a house soon. BEKE will promptly reach out to users who urgently need to sell or offer discounted prices. Standardized broker-exclusive services (specialized complementary assets) will be provided to enhance product value, achieving value innovation.

Therefore, we propose the following:

Proposition 4.

Environmental dynamics play a moderating role in the impact of specialized complementary assets on value innovation.

Based on the logic of theoretical replication, we apply Proposition 4 to Trip to verify its validity.

With advancements in AI technology (technological changes), Trip has proactively invested in the R&D of vertical models, and its content strategy has also followed, driving technological advancement through product innovation. Trip’s upgraded ranking system drives value innovation, with its word-of-mouth ranking (specialized complementary assets) continuing to contribute over 20% of traffic to merchants and nearly 10% of GMV (total merchandise transaction volume) (value innovation).

Therefore, Proposition 4 holds true in Case B as well. The dynamic environment has become a catalyst for value innovation. The pandemic restricted people’s travel, and the difficulty of viewing properties in person has accelerated the rapid adoption of VR technology. During the pandemic, BEKE utilized VR property viewing data to train AI interior design tools, extending its transaction platform into the home decoration sector. Environmental shocks have forced platforms to explore the latent functions of complementary assets (such as using property listing data to empower interior design AI) and create new value through cross-industry collaboration. This can be achieved when the platform possesses robust organizational coordination strength, enabling effective integration of diverse assets (outbound travel support services and local lifestyle support services) while avoiding internal conflicts.

Regarding the two dimensions of environmental dynamics—market changes and technological changes—we outline specific events in Table 7.

Table 7.

Representative examples of environmental dynamics.

In summary, as shown in Table 8, we compile a cross-case matrix to illustrate the convergence/divergence between the two cases.

Table 8.

Cross-case matrix.

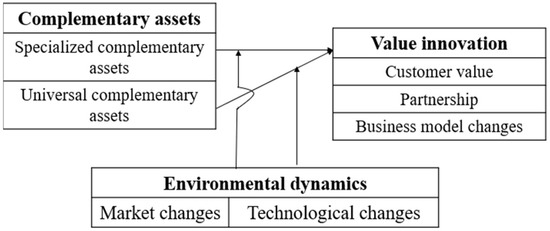

6.3. Theoretical Framework

This research further develops an impact framework of complementary assets of platform enterprises on their value innovation (Figure 1). From the perspective of value innovation, service platform enterprises identify and utilize both universal and specialized complementary assets to reconfigure their customer value, partnerships, and business model changes in the dynamic environment of technological and market changes.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework of the impact of complementary assets and environmental dynamics on service platform enterprises’ value innovation.

7. Conclusions

This research investigates how two service platform enterprises (BEKE and Trip) leverage complementary assets to drive their value innovation in dynamic environments. The innovation capability of platform enterprises has significantly improved, and their position as the innovation subject has been further enhanced. At present, there is relatively little research on complementary assets in value innovation theory. This article examines the impact and underlying framework of complementary assets and environmental dynamics on enterprises’ value innovation based on two case studies of BEKE and Trip, yielding the following conclusions:

- (1)

- Complementary assets have a promoting effect on platform enterprises’ value innovation. Furthermore, our analysis reveals that complementary assets positively influence three key dimensions of value innovation: customer value, partnership, and business model changes. Notably, both specialized complementary assets and universal complementary assets have positive effects on value innovation and customer value, partnership, and business model changes under value innovation in all three dimensions.

These findings are in line with the positive effect of specialized complementary assets on platform enterprises’ exploratory and exploitative innovation activities [62], as well as the positive impact of universal and specialized complementary assets on business model innovation [63], and is echoed by the fact that an increase in universal complementary assets will enhance value proposition for demand-side participants [22,23].

- (2)

- The environmental dynamics have moderating effects on the relationship between complementary assets and platform enterprises’ value innovation. Our analysis reveals that environmental dynamism exerts a moderating effect on both the two-dimensionality of complementary assets (specialized complementary assets, universal complementary assets) and platform enterprises’ value innovation.

These findings resonate with Berg’s AI technological advances that reshape the importance of complementary assets [64], and Wang’s related research on shifting consumer trends driving value innovation in business models [65].

7.1. Theoretical Implications

Firstly, scholarly understanding of the antecedents of value innovation remains limited. Existing literature predominantly examines value innovation processes or results, while systematic investigations of its key determinants are scarce. Based on resource-based theory, complementary assets are important assets with VRIN characteristics. Although some studies have identified the positive effects of complementary assets on innovation activities in the platform enterprise ecosystem, they fail to provide a systematic understanding of how complementary assets affect the platform enterprises’ value innovation. Addressing this unknown, we employ an exploratory multi-case study to elucidate the relationship between complementary assets and service platform enterprises’ value innovation, thereby contributing novel insights to both platform enterprise and value innovation research.

Secondly, this study establishes an integrated framework incorporating environmental dynamics, complementary assets, and value innovation. Our findings reveal (1) how complementary assets affect platform enterprises’ value innovation, and (2) the boundary conditions governing these relationships. This research makes two key theoretical contributions: first, it combines environmental dynamism with service platform enterprise value innovation; second, it extends the current understanding of contingency factors in the complementary asset–value innovation relationship.

While environmental dynamics represent a crucial contextual factor in innovation processes, the Blue Ocean Strategy literature has under-emphasized their relationship with value innovation. Our study explicitly incorporates environmental dynamics as a moderating variable, thereby enriching the research related to value innovation.

7.2. Practical Implications

The results enable us to derive the following managerial implications:

- (1)

- Value innovation approaches are a critical development strategy for platform enterprises. This study elucidates how complementary assets and environmental dynamics collectively shape platform enterprises’ value innovation. The research yields actionable insights for service platform enterprises to identify the main factors affecting enterprises’ value innovation, and help platform enterprises utilize complementary assets to develop competitive advantages, focus on specialized complementary assets (conversion of huge customer traffic, sales channel construction, and brand building), and universal complementary assets (using advanced technology, competitive production service capabilities). Consequently, service platform enterprises can enhance innovation performance in an increasingly complex, dynamic environment beyond competition, explore new markets, and significantly enhance customer value.

- (2)

- The findings of this paper enlighten China’s digital regulations. Specifically, China’s enhanced digital regulatory system, which emphasizes the collection and sharing of business entities’ credit data, has effectively recognized that a significant portion of such data constitutes platform enterprises’ complementary assets. China uses big data, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and other technical solutions to enable real-time surveillance capabilities and early warning of the market. These integrated data resources (complementary assets) now enable enriched application scenarios, empowering platform enterprises to fully leverage their proprietary data assets for value innovation in dynamic environments. Consequently, platform enterprises are incentivized to strategically maintain both their complementary assets and environmental responsiveness to sustain competitive advantages.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

However, this study nevertheless has several limitations. First, limited by data accessibility constraints, the current measurement of enterprise value innovation lacks a standardized measurement system. It relies heavily on fragmented primary enterprise survey data, which makes it difficult to form evidence under a large sample. This paper is qualitative research; the platform enterprises’ value innovation, measured based on secondary data in this paper, is just one potential measurement approach. Future research should develop more comprehensive frameworks to capture the multidimensional nature of value innovation. The authors fully acknowledge the importance of empirical research and are committed to further research to quantitatively examine the different dimensions of value innovation, and the role of complementary assets (specialized complementary assets, universal complementary assets) in shaping the different dimensions of value innovation outcomes.

Second, regarding mechanistic limitations, the intrinsic mechanism of the role of complementary assets and environmental dynamics on platform enterprises’ value innovation is to be explored in depth. Particularly, these boundaries emerge from policy environments and vertical enterprise interactions. This paper only discusses the market and technological environment; future research should investigate additional boundary conditions. Subsequent studies could leverage more comprehensive large-sample datasets to further validate and extend these findings.

Third, this study focuses on Chinese platform enterprises; their applicability may be limited by geographical constraints, and the relevant conclusions may not be fully generalizable to platform enterprises in the global context. China exhibits high levels of digitalization and strong data accessibility, with a regulatory model that prioritizes development within established norms. Platform enterprises engage in dynamic competition, and this dynamic environment enhances the impact of complementary assets on value innovation. Conversely, in regions with strictly limited data accessibility and rule-based regulation, the value conversion of data-related complementary assets may be constrained. While the positive impact of complementary assets on value innovation persists, regulatory constraints may diminish the dynamic promotion effect of the environment. Based on this, the policy recommendations are mainly targeted at China-specific enterprise survival environments. Their applicability may be limited by geographical constraints, and the relevant conclusions may not be fully generalizable to platform enterprises in the global context. It is recommended that future research conduct cross-cultural/cross-institutional comparisons in different countries or regions, and platform enterprises in other countries or regions can be selected as a control group (e.g., the United States, the European Union, Southeast Asia) to further test the applicability of the theoretical framework of this study in different cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R. and L.H.; methodology, K.R. and L.H.; software, K.R.; validation, K.R.; formal analysis, K.R. and Y.G.; investigation, K.R.; resources, K.R. and L.H.; data curation, K.R. and Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.R.; writing—review and editing, K.R.; visualization, K.R.; supervision, L.H. and Y.G.; project administration, K.R.; funding acquisition, K.R. and Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project of Zhejiang Province, China (24NDJC217YBM).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Business, Harbin Institute of Technology. (Protocol code SX-LLSC-2025-008, 9 June 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kenney, M.; Zysman, J. The Rise of the Platform Economy. Issues Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, D.P.; Srinivasan, A. Networks, platforms, and strategy: Emerging views and next steps. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, M.; Mahi, M.A.; Hassan, M.K.; Khan, S.A. Platform Economy deconstructed: Intellectual bases and emerging ethical issues. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 71, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiqi, W.; Di, S.; Yihui, L. Platform synergy and innovation speed of SMEs: The roles of organizational design and regional environment. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from innovation in the digital economy: Enabling technologies, standards, and licensing models in the wireless world. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1367–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingding, L.; Xueling, L. Environmental Dynamics, Resource Patchwork and SME Innovation. Res. Financ. Issues 2021, 4, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almquist, E.; Cleghorn, J.; Sherer, L. The B2B elements of value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2017, 96, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Belsare, H.V.; Seow, J.H.I.; Meadows, C.J. Factors Influencing Adoption of High-Value Innovation in Medical Technology Industry. In International Conference on e-Health and Bioengineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachouie, R.; Mavondo, F.T.; Ambrosini, V. Value innovation and marketing capabilities in dynamic environments: A dynamic capability perspective. J. Strateg. Mark. 2022, 32, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrigo, C.; Torres, E.J. Towards a Blue Ocean shift: Exploring value innovation for Philippine academic libraries. Libr. Manag. 2025, 46, 332–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Išoraitė, M.; Alperytė, I. How Blue Ocean Strategy helps innovate social inclusion. J. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2022, 10, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erekson, O.H.; Williams, G.B. Moving from Blue Ocean Strategy to Blue Ocean Shift in Higher Education. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2022, 28, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magued, S. Adapting Global Administrative Reforms to Local Contexts within Developing Countries: Insights into the Blue Ocean Strategy. Adm. Soc. 2023, 55, 1893–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaowu, S.; Li, Z.; Quan, G. Research on Participants Coupled Conjugate &Value Co-creation in Innovation Network of Mobile Internet Based on Service-dominant Logic. China Ind. Econ. 2013, 10, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaowei, L. Enterprise Value Innovation in the Era of E-commerce. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2001, 22, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, C.C. A longitudinal study of the influence of alliance network structure and composition on firm exploratory innovation. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 890–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Yanan, F. Empirical Research of Cross-system Entrepreneurial Network Structure on Value Innovation. Sci. Technol. Manag. 2014, 35, 96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Zuoliang, L. A Modular Study on Value Innovation in Cultural and Creative Industries from the Perspective of Knowledge Management. Ph.D. Thesis, Fudan University, Shanghai, China, 2014. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=d7HKHDfP4kfcE7HMnJbHmDfWeQuNEoHP2Yznq9A2NVWEfyrrqe8NrhL8078rMiU45j_ueIADY91GU0OEGYodZo-myZiYcCjcXFveJkFvJSKogs2fYzlyotdrk4_RIwlEH8KyzfIYcQiu3SPybjDtZFM_NOd-Hl7Tr8Hh4f3uaOK_7e685P6-iTiyZy5sl8am&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Mirza, S.; Mahmood, A.; Waqar, H. The interplay of open innovation and strategic innovation: Unpacking the role of organizational learning ability and absorptive capacity. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2022, 14, 18479790211069745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, T. Does the national risk of overseas investment affect the strategic innovation behavior of enterprises? Evidence from China. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 43, 1548–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerderer, J. Interfirm exchange and innovation in platform ecosystems: Evidence from Apple’s worldwide developers conference. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 4359–4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Wright, M.; Ketchen, D. Editorial The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2021, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Beard, D.W. Dimensions of organizational task environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 1984, 29, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A.; Helfat, C.E. Organizational linkages for surviving technological change: Complementary assets, middle management, and ambidexterity. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 718–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, A.M.; Rothaermel, F.T. When are assets complementary? Star scientists, strategic alliances, and innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 895–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Raubitschek, R.S. Dynamic and integrative capabilities for profiting from innovation in digital platform-based ecosystems. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1391–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, S. The inside track: Entrepreneurs’ corporate experience and startups’ access to incumbent partners’ resources. Strateg. Manag. J. 2024, 45, 1117–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenmann, T.; Parker, G.; Alstyne, M.W.V. Strategies for two-sided markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 92–101+149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Iansiti, M. Entry into platform-based markets. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothaermel, F.T. Incumbent’s advantage through exploiting complementary assets via interfirm cooperation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Xu, X.; Jiang, C. Complementary assets, dual learning and innovative capabilities: Examining the catch-up process of late-start firms in emerging economies. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2025, 38, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, K.; Hu, L. Complementary assets, organizational modularization, and platform enterprise value innovation. Systems 2023, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.C.; Mauborgne, R. Value innovation: The strategic logic of high growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 75, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J.A.; Rossum, W.V. Customer value propositions in business markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.M.; Liu, J.; Qiao, S.H. How can enterprises achieve transformation and upgrading through continuous value innovation? A longitudinal case study based on the perspective of intermittent balance. J. Manag. Case Study 2021, 14, 355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Kreuz, P. Strategic innovation: The construct, its drivers and its strategic outcomes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2003, 11, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Gao, S.H. The influence mechanism of employee orientation on original innovation. Sci. Res. Manag. 2022, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajar, M.A.; Alkahtani, A.A.; Ibrahim, D.N.; Darun, M.R.; Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Tiong, S.K. The Approach of Value Innovation towards Superior Performance, Competitive Advantage, and Sustainable Growth: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, J. Organization structure and strategies of control: A replication of the Aston study. Adm. Sci. Q. 1972, 17, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbusch, N.; Bausch, A.; Galander, A. The impact of environmental characteristics on firm performance: A meta-analysis. In Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings; Academy of Management: Valhalla, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 2007, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Acosta, P.; Popa, S.; Martinez-Conesa, I. Information technology, knowledge management and environmental dynamism as drivers of innovation ambidexterity: A study in SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 824–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongmei, W. Research on the Relationship Between Organizational Modularization, Dynamic Capability, and Value Innovation. Ph.D. Thesis, Xi’an University of Technology, Xi’an, China, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.; Hao, R.; Jianjun, W. The Research of the Impact of the Governances Capacity of the Core Enterprise on the Value Innovation of Modular Organization: The Moderating Effect of Environmental Dynamism. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2017, 34, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? J. Manag. 2017, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Shuen, P.A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokshagina, O. Managing shifts to value-based healthcare and value digitalization as a multi-level dynamic capability development process. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2021, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.G. Understanding dynamic capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hienerth, C.; Lettl, C.; Keinz, P. Synergies among producer firms, lead users, and user communities: The case of the lego producer–user ecosystem. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.Q.; Zhang, Y.M.; Lin, J.J. Context Identification and Mechanism Analysis of Why Enterprises Choose Specialization Strategy in Emerging Countries: Based on a Multiple-case Study of the Enterprises in Shenzhen. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenhuis, H.J.; Bruijn, E. Building Theories from Case Study Research: The Progressive Case Study. In Proceedings of the 17th Annual Conference of POMS, Boston, MA, USA, 28 April–1 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. What is the Eisenhardt Method, really? Strateg. Organ. 2021, 19, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, W.K. Triangulation in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods Can Really Be Mixed. In Developments in Sociology; Causeway Press Ltd.: London, UK, 2004; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236144423_Triangulation_in_social_research_Qualitative_and_quantitative_methods_can_really_be_mixed (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Benlian, A. Options for Formulating a Digital Transformation Strategy. MIS Q. Exec. 2016, 15, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Helfat, C.E. Know-how and asset complementarity and dynamic capability accumulation: The case of R&D. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Yunxia, S.; Tao, S.; Minggui, S. Research on Complementary Assets: Review and Outlook. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2013, 35, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghman, L.; Matthyssens, P.; Vandenbempt, K. Value innovation, deliberate learning mechanisms and information from supply chain partners. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, B.; Guerin, A.M. Organizational Modularity, Product Characteristics and Organizational Value Innovation. Nankai Econ. Rev. 2011, 2, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y. Specialized complementary assets and disruptive innovation: Digital capability and ecosystem embeddedness. Manag. Decis. 2024, 62, 3704–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, R.H. Research on the Impact of Complementary Assets and Platform Leadership on Ambidextrous Innovation: Moderating Effect of Environmental Complexity. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheng, L.; Zhou, H. Does digital platform capability enable Chinese SMEs’ business model innovation? The role of complementary assets and entrepreneurial orientation. Asian J. Technol. Innov. 2024; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Raj, M.; Seamans, R. Capturing value from artificial intelligence. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2023, 9, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Liu, J.H.; Chang, Q. How does Scenario Chain Create Value Based on Supply Chain Enabling New Retail Business Model: Case Study of Foton. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T 2022, 43, 135–155. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).