Reconstruction of Logistics Services in Cross-Border E-Commerce and Consumer Continuance Intention on Platforms: The Mediating Role of Digital Logistics Services

Abstract

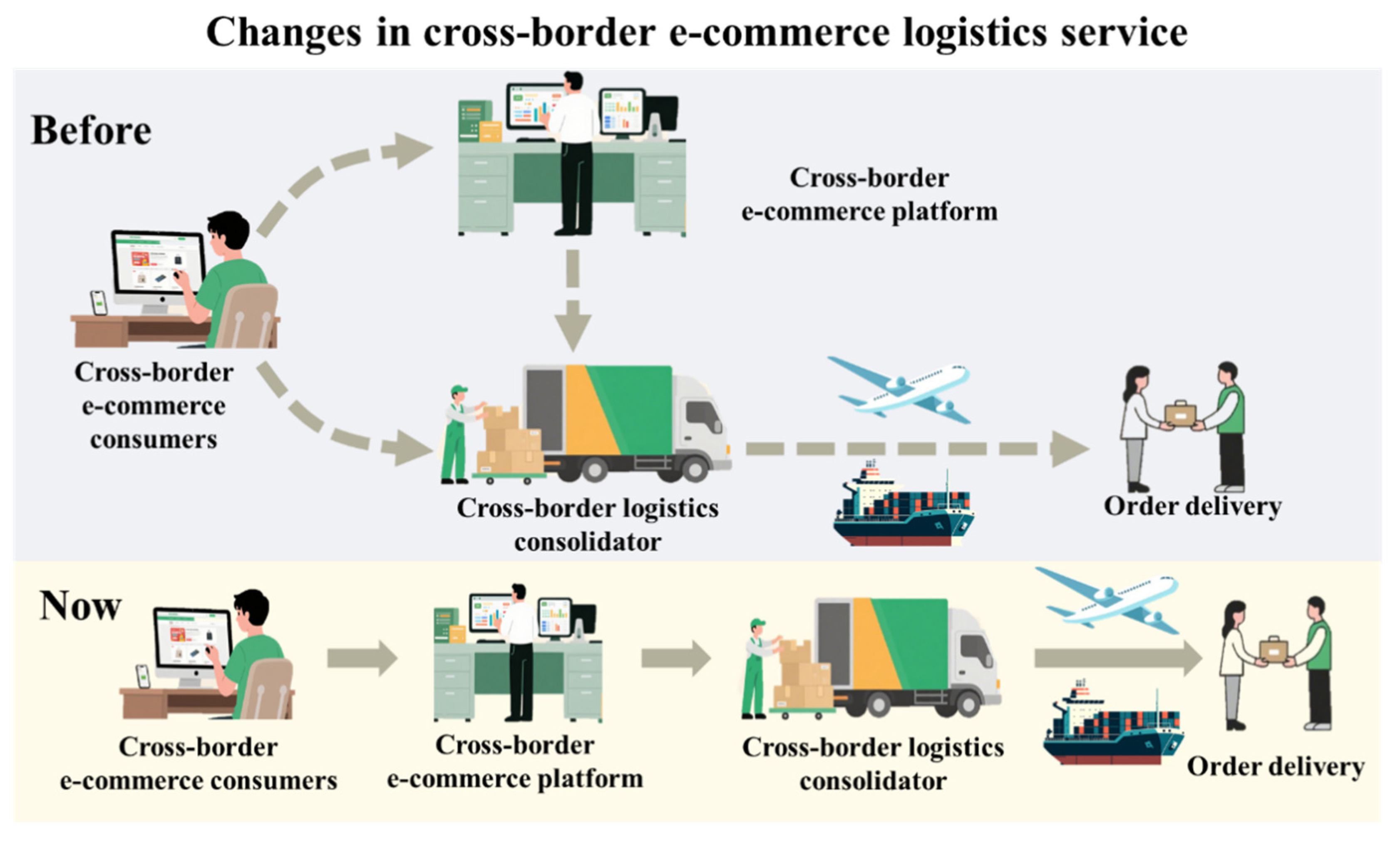

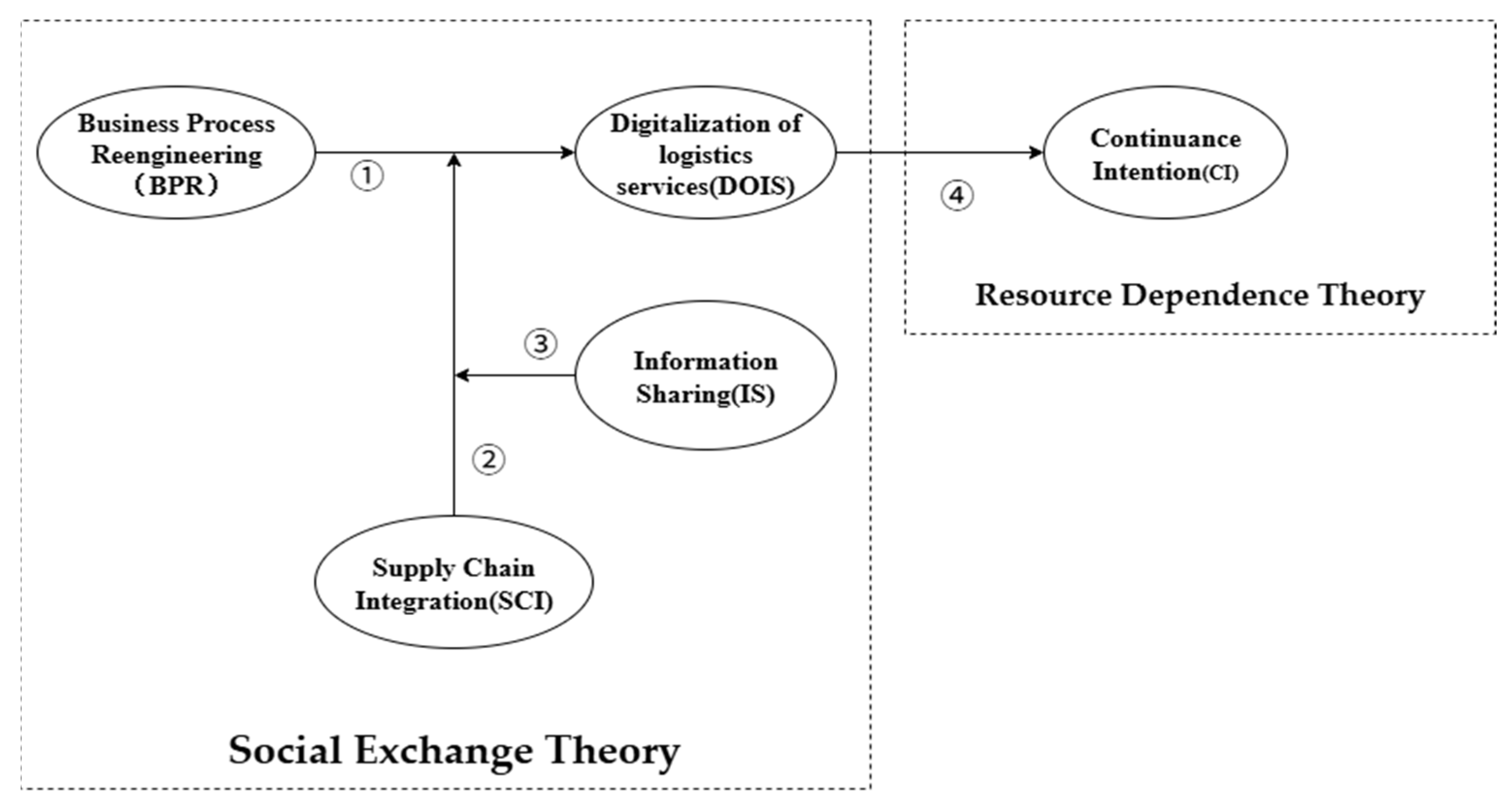

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Exchange Theory

2.2. Resource Dependence Theory

2.3. Hypothesis Development

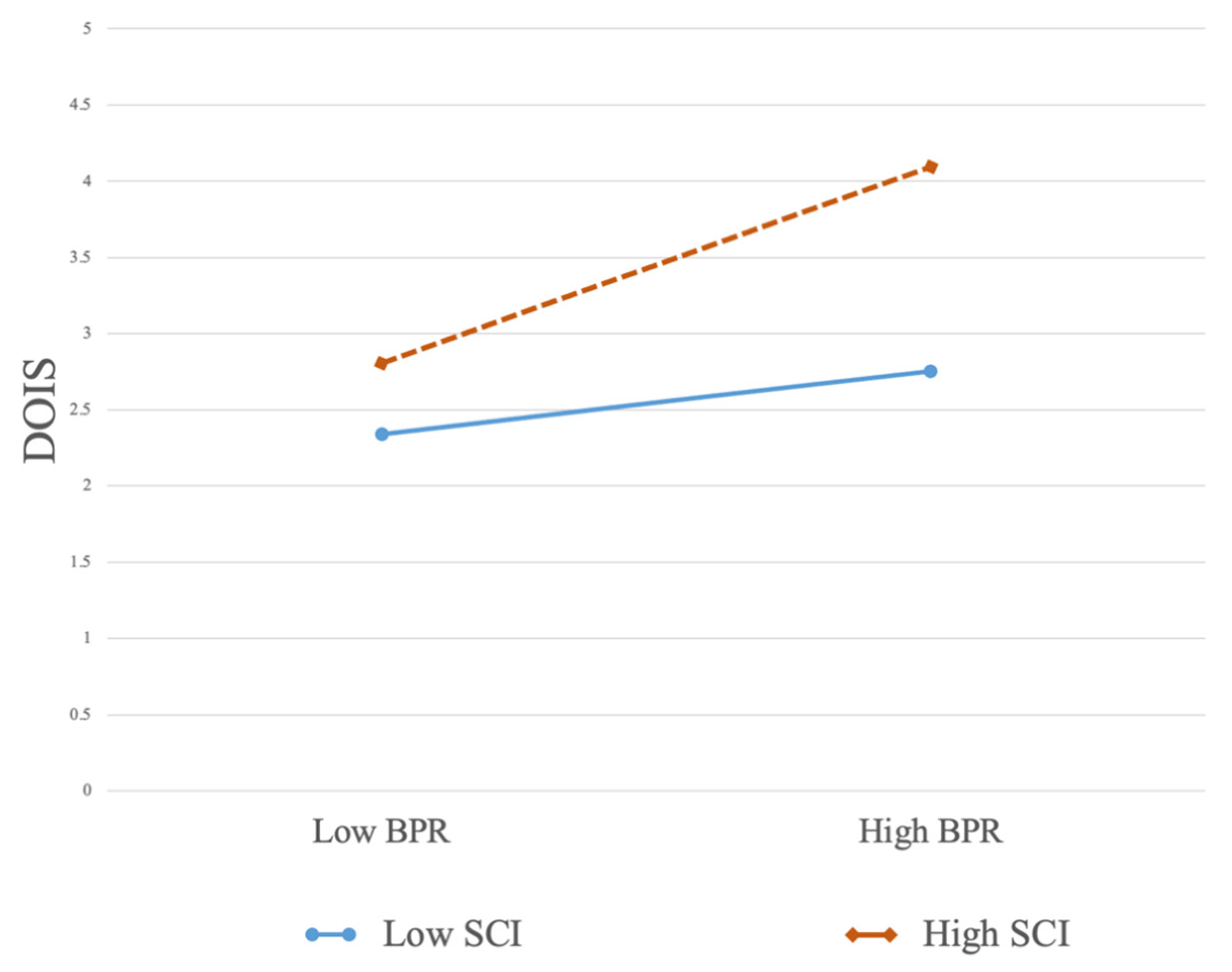

2.3.1. Three-Way Interaction Effect of Information Sharing

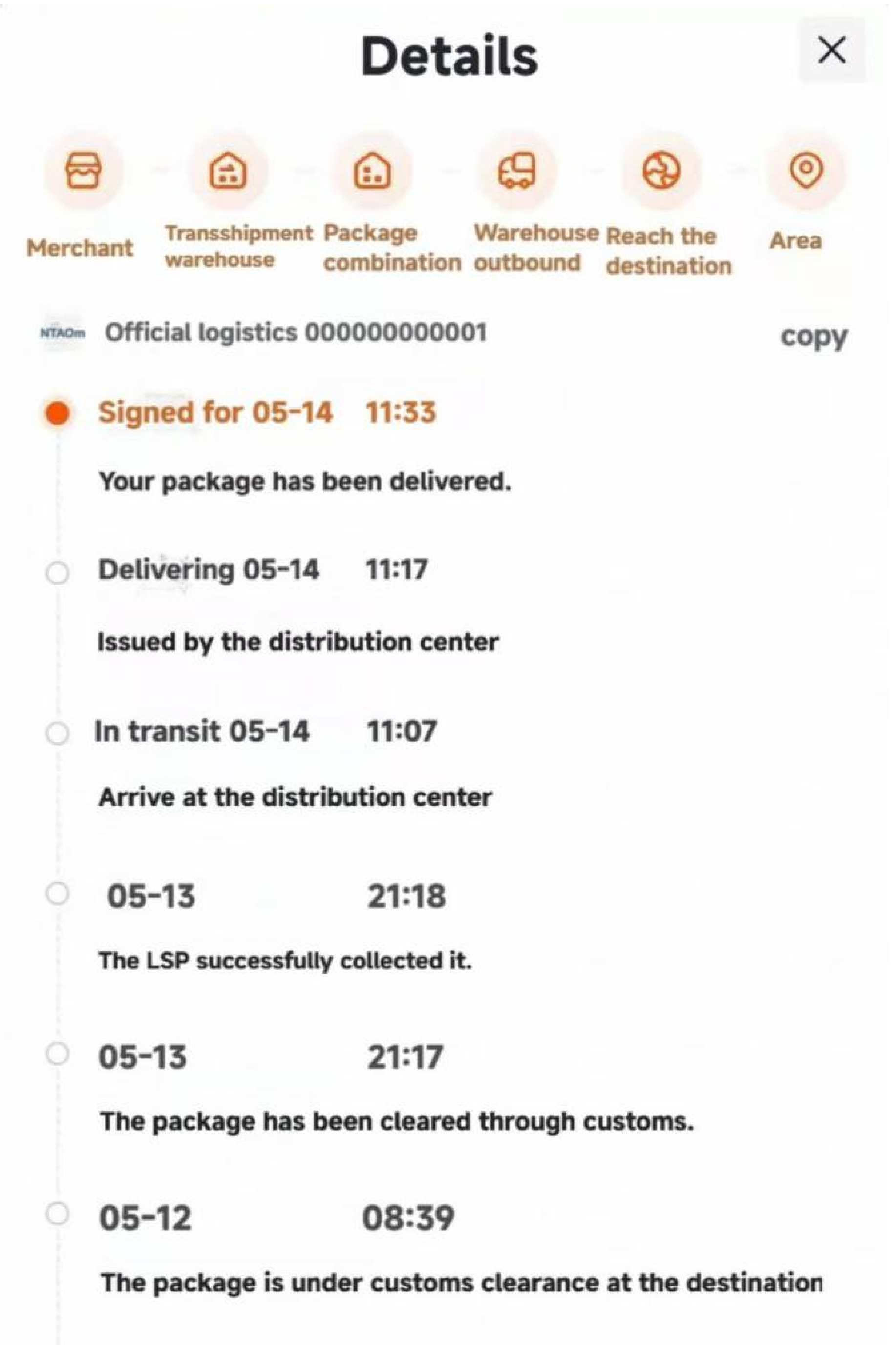

2.3.2. The Impact of Logistics Service Digitization on Platform Continuance Intention

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measurement Items and Bias Testing

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.1.1. Reliability

4.1.2. Convergent Validity

4.1.3. Discriminant Validity

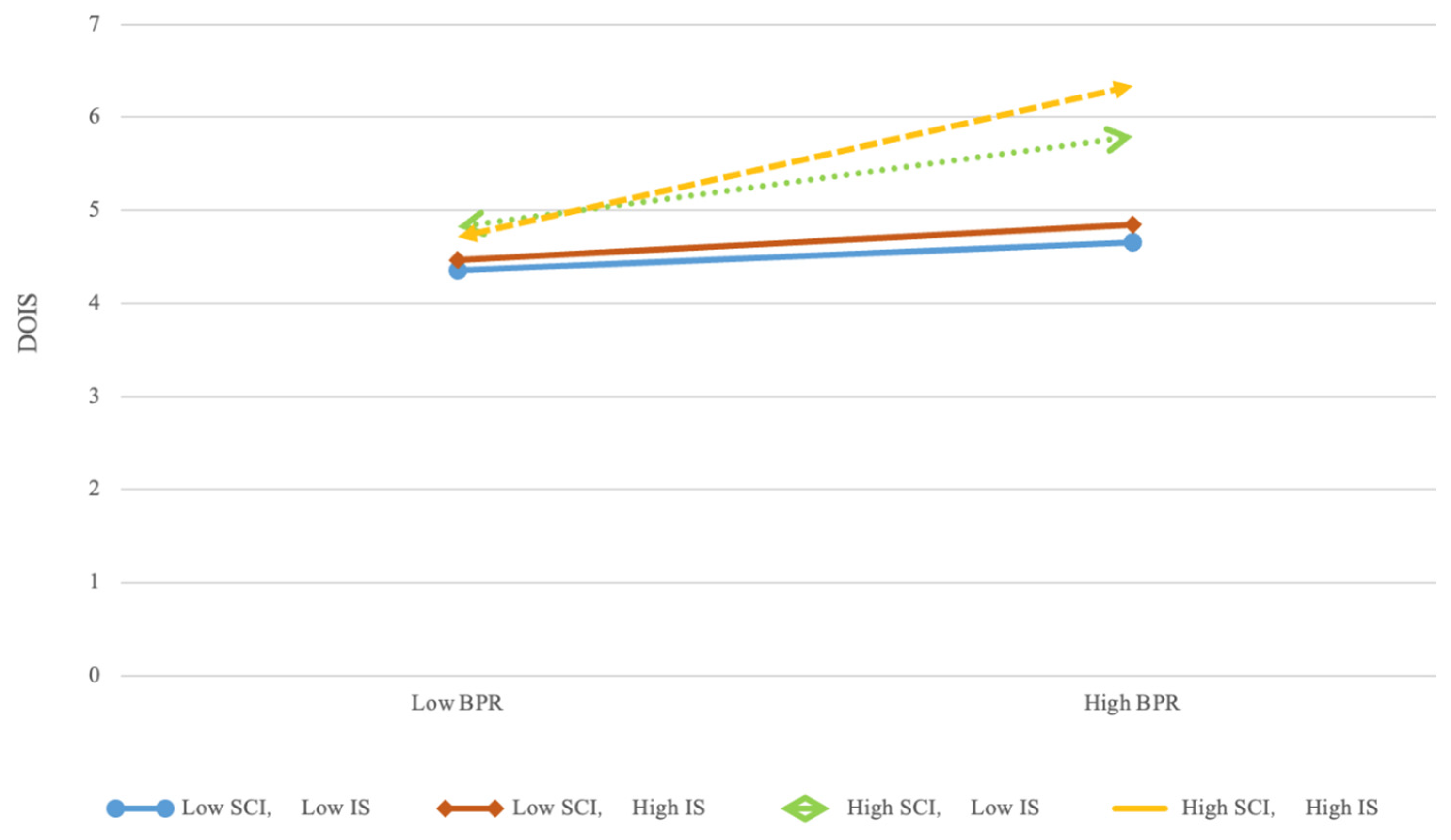

4.2. Hypothesis Testing Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

5.2. Practical Implication

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Pu, W. Measuring ease of use of mobile applications in e-commerce retailing from the perspective of consumer online shopping behaviour patterns. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Osewe, M.; Shi, Y.; Zhen, X.; Wu, Y. Cross-border e-commerce development and challenges in China: A systematic literature review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 17, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrauf, S.; Berttram, P. Industry 4.0: How digitization makes the supply chain more efficient. Agile, and customer-focused. Strateg. Technol. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Lan, Y.C.; Chang, Y.W. Consumer behaviour in cross-border e-commerce: Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 2609–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Cohen, J.; Dou, Y.; Zhang, B. International buyers’ repurchase intentions in a Chinese cross-border e-commerce platform: A valence framework perspective. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 403–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Bao, Y.; Stuart, B.J.; Le-Nguyen, K. To sell or not to sell: Exploring sellers’ trust and risk of chargeback fraud in cross-border electronic commerce. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, T.K.; Fichman, M.; Kraut, R.E. Trust Across Borders: Buyer-Supplier Trust in Global Business-to-Business E-Commerce. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2013, 13, 886–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Ladhari, R.; Chiadmi, N.E. New trends in retailing and services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, M.X. The influences of livestreaming on online purchase intention: Examining platform characteristics and consumer psychology. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 862–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, C.; Eggers, F.; Verhoef, P.C.; Maas, P. The effects of cultural differences on consumers’ willingness to share personal information. J. Interact. Mark. 2023, 58, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Xu, Y.; Xu, X. The effects of trust and platform innovation characteristics on consumer behaviors in social commerce: A social influence perspective. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 60, 101284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Yang, Y. The impact of customer experience on consumer purchase intention in cross-border E-commerce—Taking network structural embeddedness as mediator variable. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosillo-Díaz, E.; Blanco-Encomienda, F.J.; Crespo-Almendros, E. A cross-cultural analysis of perceived product quality, perceived risk and purchase intention in e-commerce platforms. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 33, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainardes, E.W.; de Souza, I.M.; Correia, R.D. Antecedents and consequents of consumers not adopting e-commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichosz, M.; Wallenburg, C.M.; Knemeyer, A.M. Digital transformation at logistics service providers: Barriers, success factors and leading practices. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2020, 31, 209–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, M.; Montanari, R.; Bottani, E. Improving the efficiency of public administrations through business process reengineering and simulation: A case study. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2015, 21, 419–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, M.; Mangiaracina, R.; Perego, A.; Tumino, A. Cross-border B2C e-commerce to China: An evaluation of different logistics solutions under uncertainty. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2020, 50, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Zhang, Z.; Rose, J. Transport and logistics challenges for China: Drivers of growth, and bottlenecks constraining development. Road Transp. Res. J. Aust. N. Z. Res. Pract. 2015, 24, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Huang, J.; Wu, K.; Huang, X.; Kong, N.; Campy, K.S. Characterizing Chinese consumers’ intention to use live e-commerce shopping. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Pan, X. The effects of digital technology application and supply chain management on corporate circular economy: A dynamic capability view. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 341, 118082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, S.; Sparks, L. E-commerce and the retail process: A review. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2003, 10, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfmann, W.; Albers, S.; Gehring, M. The impact of electronic commerce on logistics service providers. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2002, 32, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, O.; Bağış, M. Bridging resource dependence theory and resource-based view: A theoretical synthesis. Manag. Decis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.B.; Huo, B.; Zhao, X. The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach. J. Oper. Manag. 2010, 28, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, M.; Jiang, H.; Mangiaracina, R. Investigating the relationships between uncertainty types and risk management strategies in cross-border e-commerce logistics. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 1406–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An Interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, F.; Tan, K.H. Effects of managerial ties and trust on supply chain information sharing and supplier opportunism. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 7046–7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource dependence theory: A review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Subramanian, N.; Papadopoulos, T. Information technology for competitive advantage within logistics and supply chains: A review. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2017, 99, 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Mou, J.; Benyoucef, M. Exploring purchase intention in cross-border E-commerce: A three stage model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homans, G.C. Social Behavior as Exchange. Am. J. Sociol. 1958, 63, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, H.H. The Social Psychology of Groups; Transaction Publishers: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Pulles, N.J.; Veldman, J.; Schiele, H.; Sierksma, H. Pressure or Pamper? The Effects of Power and Trust Dimensions on Supplier Resource Allocation. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, B.; Liu, J.; Dai, F.; Kang, M. Understanding the impact of buyer extra-role behavior on supply-side operational transparency: A serial mediation model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 266, 109041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallocchio, M.; Lambri, M.; Sironi, E.; Teti, E. The role of digitalization in cross-border e-commerce performance of Italian SMEs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Nath, B. The role of information technology in business process reengineering. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1997, 50, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.M.; Ting, S.C.; Chen, M.C. Evaluating the cross-efficiency of information sharing in supply chains. Expert Syst. Appl. 2010, 37, 2891–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Liu, Y. Blockchain-enabled cross-border e-commerce supply chain management: A bibliometric systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertz, M.; Sarigöllü, E. Consumer intentions to use collaborative economy platforms: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 1859–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ayodeji, O.G. E-retail factors for customer activation and retention: An empirical study from Indian e-commerce customers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.A.; Harvey, M.G.; Lusch, R.F. Social exchange in supply chain relationships: The resulting benefits of procedural and distributive justice. J. Oper. Manag. 2006, 24, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, A.; Chen, I.J. Environmental uncertainty and strategic supply management: A resource dependence perspective and performance implications. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2007, 43, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, Y.; Xia, J.; Hitt, M.; Shen, J. Resource dependence theory in international business: Progress and prospects. Glob. Strategy J. 2023, 13, 3–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, V.; Jeong, S.R.; Kettinger, W.J.; Teng, J.T. The implementation of business process reengineering. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1995, 12, 109–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J. Innovation of cross border e-commerce supply chain management mechanism under digital background. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 2025, 32, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. A model for implementing BPR based on strategic perspectives: An empirical study. Inf. Manag. 2002, 39, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, A.; Downs, D.; Lunn, K. Business processes—Attempts to find a definition. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2003, 45, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.; Gheitasi, M.; Soltani, F. Fuzzy model on selecting processes in Business Process Reengineering. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2016, 22, 1118–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidovic, D.I.; Vuksic, V.B. Dynamic business process modelling using ARIS. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Information Technology Interfaces, ITI 2003, Cavtat, Croatia, 19 June 2003; pp. 607–612. [Google Scholar]

- Niehaves, B.; Plattfaut, R. Collaborative business process management: Status quo and quo vadis. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2011, 17, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, A.; Monge, F.; Mueller, J. Ambidextrous IT capabilities and business process performance: An empirical analysis. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2018, 24, 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, N.; Chen, H. The digital platform, enterprise digital transformation, and enterprise performance of cross-border e-commerce—From the perspective of digital transformation and data elements. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathauer, M.; Hofmann, E. Technology adoption by logistics service providers. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayikci, Y. Sustainability impact of digitization in logistics. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 21, 782–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y. Influencing factors of consumer willingness to pay for cold chain logistics: An empirical analysis in China. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2019, 10, 3279–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameri, A.P.; Hintsa, J. Assessing the drivers of change for cross-border supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 741–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, G.; Al Mamun, A.; Reza, M.N.H.; Hussain, W.M.H.W. An empirical study on logistic service quality, customer satisfaction, and cross-border repurchase intention. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, T.M.; Prabhakar, G. What factors determine e-satisfaction and consumer spending in e-commerce retailing? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostic, D.; Obrenovic, B. JD Strategic Cross-Border Expansion-Offering Retail as Strategy Solutions Abroad. In Casebook of Chinese Business Management; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2022; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, R.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, X. Evaluating consumers’ willingness to pay for delay compensation services in intra-city delivery—A value optimization study using choice. Information 2021, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Deokar, A.; Lee, H.C.B.; Summerfield, N. The role of commitment in online reputation systems: An empirical study of express delivery promise in an E-commerce platform. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 176, 114061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wan, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, C. Implementing Smart Factory of Industrie 4.0: An Outlook. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2016, 12, 3159805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrucco, A.; Ciccullo, F.; Pero, M. Industry 4.0 and supply chain process re-engineering: A coproduction study of materials management in construction. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2020, 26, 1093–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jia, F.; Schoenherr, T.; Gong, Y.; Chen, L. Cross-border e-commerce firms as supply chain integrators: The management of three flows. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 89, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Prajogo, D.; Oke, A. Supply Chain Technologies: Linking Adoption, Utilization, and Performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2016, 52, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Lin, Y.; Xie, D.; Zhang, J. Effect of intelligent logistics policy on shareholder value: Evidence from Chinese logistics companies. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 137, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.L.; Chuang, C.H.; Hsu, C.H. Information sharing and collaborative behaviors in enabling supply chain performance: A social exchange perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 148, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçoǧlu, I.; Imamoǧlu, S.Z.; Ince, H.; Keskin, H. The effect of supply chain integration on information sharing: Enhancing the supply chain performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 1630–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajja, M.S.S.; Chatha, K.A.; Farooq, S. Impact of supply chain risk on agility performance: Mediating role of supply chain integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 205, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdana, Y.R.; Ciptono, W.S.; Setiawan, K. Broad span of supply chain integration: Theory development. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.D.; Roh, J.; Tokar, T.; Swink, M. Leveraging supply chain visibility for responsiveness: The moderating role of internal integration. J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 31, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Boonitt, S.; Wong, C.W.Y. The contingency effects of environmental uncertainty on the relationship between supply chain integration and operational performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swink, M.; Narasimhan, R.; Wang, C. Managing beyond the factory walls: Effects of four types of strategic integration on manufacturing plant performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 148–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, T.; Swink, M. Revisiting the arcs of integration: Cross-validations and extensions. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.; Jajja, M.S.S.; Chatha, K.A.; Farooq, S. Supply chain risk management and operational performance: The enabling role of supply chain integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.G.; Katz, P.B. Strategic Sourcing. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 1998, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-M.; Hung, S.-W. Supply chain relationship quality and performance in technological turbulence: An artificial neural network approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 2757–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W. An investigation on the direct and indirect effect of supply chain integration on firm performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 119, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-L.; Lee, M.-Y. Integration, supply chain resilience, and service performance in third-party logistics providers. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2018, 29, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Mendoza, J.A.; Neailey, K.; Roy, R. Business process re-design methodology to support supply chain integration. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D.; Olhager, J. Supply chain integration and performance: The effects of long-term relationships, information technology and sharing, and logistics integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 135, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reaidy, P.J.; Gunasekaran, A.; Spalanzani, A. Bottom-up approach based on Internet of Things for order fulfillment in a collaborative warehousing environment. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 159, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Gunasekaran, A.; Ngai, E.W.T.; Papadopoulos, T. Big data analytics in logistics and supply chain management: Certain investigations for research and applications. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 176, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J.; Fang, M.; Yao, J.; Su, M. Green cooperation in last-mile logistics and consumer loyalty: An empirical analysis of a theoretical framework. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 73, 103308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Su, Y.; Fang, M.; Su, M. Embracing new energy vehicles: An empirical examination of female consumer perspectives. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 80, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruquee, M.; Paulraj, A.; Irawan, C.A. Strategic supplier relationships and supply chain resilience: Is digital transformation that precludes trust beneficial? Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 41, 1192–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Singh, R.K.; Papadopoulos, T. Linking digital orientation and data-driven innovations: A SAP–LAP linkage framework and research propositions. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 71, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, M.; Saunila, M.; Rantala, T.; Ukko, J. Sustainable innovation among small businesses: The role of digital orientation, the external environment, and company characteristics. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Liu, K.; Li, L.; Lai, K.-H.; Zhan, Y.; Kumar, A. Digital supply chain management in the COVID-19 crisis: An asset orchestration perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 245, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gao, G.; Xiao, X.; Zuo, H. Factors and formation path of cross-border E-commerce logistics mode selection. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, X.; Kim, R.; Su, M. Anthropomorphic last-mile robots and consumer intention: An empirical test under a theoretical framework. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester. Forrester Research Online Retail Forecast, 2014 to 2019 (Asia Pacific); Report; Forrester: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EMarketer. China Ecommerce: 2015 Market Update; Report; eMarketer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Terziovski, M.; Fitzpatrick, P.; O’Neill, P. Successful predictors of business process reengineering (BPR) in financial services. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2003, 84, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Liu, F.; Xiao, S.; Park, K. Hedging the bet on digital transformation in strategic supply chain management: A theoretical integration and an empirical test. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2023, 53, 512–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ye, F.; Sheu, C. Social capital, information sharing and performance: Evidence from China. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2014, 34, 1440–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, L.D.; Behl, A.; Phuong, N.N.D.; Gaur, J.; Dzung, N.T. Toward SME digital transformation in the supply chain context: The role of structural social and human capital. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2023, 53, 448–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Pan, Q. Research on value creation path of logistics platform under the background of digital ecosystem: Based on SEM and fsQCA methods. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 67, 101424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, T.H.; Lee, C.T.; Huang, H.T.; Yang, W.H. Success factors driving consumer reuse intention of mobile shopping application channel. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2022, 50, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, C. Predicting mobile government service continuance: A two-stage structural equation modeling-artificial neural network approach. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, 39, 101654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, W.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate data analysis: Its approach, evolution, and impact. In The Great Facilitator: Reflections on the Contributions of Joseph F. Hair, Jr. to Marketing and Business Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Rethinking some of the rethinking of partial least squares. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.L.; Chang, Y.C. Cross-border e-commerce: Consumers’ intention to shop on foreign websites. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 1256–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Lin, Y.C.; Bag, A.; Chen, C.L. Influence factors of small and medium-sized enterprises and micro-enterprises in the cross-border e-commerce platforms. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 416–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Flynn, B.B.; Yeung, J.H.Y. The impact of power and relationship commitment on the integration between manufacturers and customers in a supply chain. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Battistella, C.; Nonino, F.; Parida, V.; Pessot, E. Literature review on digitalization capabilities: Co-citation analysis of antecedents, conceptualization and consequences. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, B.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, H. The Effects of Competitive Environment on Supply Chain Information Sharing and Performance: An Empirical Study in China. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2014, 23, 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D.; Dolgui, A. A digital supply chain twin for managing the disruption risks and resilience in the era of Industry 4.0. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, 32, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, G.; Kamble, S.S.; Ndubisi, N.O.; Shrivastava, A.; Belhadi, A.; Venkatesh, M. Antecedents of Blockchain-Enabled E-commerce Platforms (BEEP) adoption by customers—A study of second-hand small and medium apparel retailers. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 149, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measurement Item | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Business Process Reengineering (BPR) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) BPR1. My company has redesigned key logistics processes related to consumer interactions by deploying information technology. BPR2. We restructured our consumer-facing logistics business processes to improve process flexibility and consumer responsiveness. BPR3. My company undertook an organization-wide and cross-functional redesign of processes related to consumer logistics. BPR4. After restructuring the logistics process for consumers, my company has improved the overall management decision-making response speed. BPR5. Our company sees the reengineering of consumer logistics processes as a key strategic initiative. | |

| Digitalization of logistics services(DOIS) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) DOIS1. Our logistics services utilize digital technologies to respond rapidly to cross-border e-commerce demands. DOIS2. Technologies, such as Internet of Things (IoT) applications, enhance real-time monitoring of logistics operations. DOIS3. Customers can access updated order status at any time through our digital logistics platform. DOIS4. Our digital logistics systems support automatic tracking and timely delivery. DOIS5. The platform improves coordination and communication efficiency with supply chain partners. DOIS6. We provide end-to-end logistics services through digital platforms to meet diverse customer needs. DOIS7. Our company continuously invests in logistics digitalization to enhance service innovation. | |

| Supply Chain Integration (SCI) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) SCI1. My company has established a stable cooperative relationship with multinational logistics service providers to achieve the integration and optimization of cross-border logistics processes. SCI2. My company maintains efficient communication with the cross-border logistics service provider at all organizational levels. SCI3. My company’s platform supply chain team and logistics service providers have achieved effective collaboration in key operational links. SCI4. Strategic cooperation with cross-border logistics suppliers has enhanced our company’s ability to implement the cross-border e-commerce platform strategy. SCI5. Our company aligns operational goals with long-term cross-border logistics partners to achieve supply chain synergy and integration. |

|

| Information Sharing(IS) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) IS1. Our supply chain partners share accurate and complete logistics information with us. IS2. Our company has established systems to enable seamless exchange of supply chain data. IS3. The information shared by my supply chain members is timely and complete. IS4. The information shared by my supply chain members with us is sufficient and reliable. |

|

| Continuance Intention (CI) | Strongly disagree (1)/Strongly agree (7) CI1. Our customers frequently return to use our platform for shopping. CI2. Many customers repeatedly place orders through our platform. CI3. Our platform has a high rate of returning customers. CI4. Most of our active users continue to make purchases on our platform over time. |

| Items | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firm size (FS) | 1–10 | 98 | 46.9% |

| 11–50 | 75 | 35.9% | |

| 51–200 | 30 | 14.4% | |

| >200 | 6 | 2.9% | |

| Total sales (TS) (USD) | <$100,000 | 56 | 26.8% |

| $100,000–$500,000 | 65 | 31.1% | |

| $500,000–$1 Million | 42 | 20.1% | |

| $1 Million–$5 Million | 32 | 15.3% | |

| $5 Million–$10 Million | 9 | 4.3% | |

| >$10 Million | 5 | 2.4% | |

| Firm age (FA) (years) | <1 | 32 | 15.3% |

| 1–3 | 87 | 41.6% | |

| 3–5 | 55 | 26.3% | |

| >5 | 35 | 16.7% | |

| Main industry (MI) | Consumer electronics | 52 | 24.9% |

| Fashion clothing | 45 | 21.5% | |

| Home life | 38 | 18.2% | |

| Sports and outdoor | 16 | 7.7% | |

| Beauty | 19 | 9.1% | |

| Mother and baby pets | 39 | 18.7% | |

| R&D investment (RDI) ratio/(annual revenue) | <1% | 89 | 42.6% |

| 1–3% | 67 | 32.1% | |

| 3–5% | 32 | 15.3% | |

| 5–10% | 15 | 7.2% | |

| >10% | 6 | 2.9% |

| Construct | Item | Mean | SD | λ | alpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPR | BPR1 | 5.019 | 1.411 | 0.828 | 0.939 | 0.756 | 0.887 |

| BPR2 | 5.215 | 1.372 | 0.902 | ||||

| BPR3 | 5.144 | 1.454 | 0.878 | ||||

| BPR4 | 5.005 | 1.382 | 0.849 | ||||

| BPR5 | 5.081 | 1.447 | 0.888 | ||||

| DOIS | DOIS1 | 5.163 | 1.391 | 0.823 | 0.947 | 0.717 | 0.947 |

| DOIS2 | 5.019 | 1.441 | 0.866 | ||||

| DOIS3 | 4.947 | 1.458 | 0.784 | ||||

| DOIS4 | 5.072 | 1.359 | 0.831 | ||||

| DOIS5 | 5.129 | 1.393 | 0.864 | ||||

| DOIS6 | 5.124 | 1.353 | 0.894 | ||||

| DOIS7 | 5.134 | 1.352 | 0.862 | ||||

| SCI | SCI1 | 4.746 | 1.534 | 0.882 | 0.953 | 0.804 | 0.894 |

| SCI2 | 4.656 | 1.534 | 0.886 | ||||

| SCI3 | 4.598 | 1.494 | 0.903 | ||||

| SCI4 | 4.766 | 1.684 | 0.875 | ||||

| SCI5 | 4.689 | 1.627 | 0.937 | ||||

| IS | IS1 | 5.187 | 1.240 | 0.817 | 0.899 | 0.695 | 0.901 |

| IS2 | 5.206 | 1.394 | 0.810 | ||||

| IS3 | 5.172 | 1.282 | 0.793 | ||||

| IS4 | 5.335 | 1.331 | 0.910 | ||||

| CI | CI1 | 3.416 | 1.276 | 0.797 | 0.862 | 0.616 | 0.865 |

| CI2 | 3.574 | 1.396 | 0.827 | ||||

| CI3 | 3.440 | 1.104 | 0.796 | ||||

| CI4 | 3.416 | 1.186 | 0.714 |

| BPR | DOIS | SCI | IS | CI | FA | FS | RDI | TS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPR | 0.869 | ||||||||

| DOIS | 0.199 *** | 0.847 | |||||||

| SCI | 0.214 *** | 0.400 *** | 0.897 | ||||||

| IS | 0.177 ** | 0.462 *** | 0.234 *** | 0.834 | |||||

| CI | 0.323 *** | 0.315 *** | 0.325 *** | 0.285 *** | 0.784 | ||||

| FA | −0.013 | −0.193 *** | −0.184 *** | −0.020 | −0.030 | - | |||

| FS | −0.009 | 0.007 | −0.033 | 0.011 | 0.046 | 0.164 ** | - | ||

| RDI | −0.008 | 0.300 *** | 0.292 *** | 0.155 ** | 0.216 *** | −0.138 ** | −0.105 | - | |

| TS | 0.046 | 0.154 ** | 0.078 | 0.130 * | 0.044 | −0.008 | 0.227 *** | 0.090 | - |

| Dependent Variable (DV) = DOIS | DV = CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Firm age | −0.2659 ** | −0.2071 ** | −0.1774 ** | −0.1816 ** | −0.1963 ** | −0.2149 *** | 0.0350 |

| (0.1104) | (0.0973) | (0.0857) | (0.0853) | (0.0862) | (0.0818) | (0.1017) | |

| Firm size | 0.0335 | 0.0316 | 0.0099 | 0.0042 | 0.0162 | 0.0281 | −0.0238 |

| (0.0657) | (0.0572) | (0.0504) | (0.0503) | (0.0503) | (0.0477) | (0.0597) | |

| R & D investment | 0.4073 *** | 0.2289 ** | 0.1694 ** | 0.1530 * | 0.1422 * | 0.1616 ** | −0.1002 |

| (0.1002) | (0.0908) | (0.0803) | (0.0805) | (0.0799) | (0.0758) | (0.0946) | |

| Total sales | 0.0912 * | 0.0490 | 0.0296 | 0.0318 | 0.0320 | 0.0270 | 0.0165 |

| (0.0511) | (0.0448) | (0.0395) | (0.0393) | (0.0395) | (0.0374) | (0.0468) | |

| BPR | 0.2309 *** | 0.4250 *** | 0.4017 *** | 0.4178 *** | 0.4090 *** | ||

| (0.0587) | (0.0573) | (0.0588) | (0.0588) | (0.0557) | |||

| SCI | 0.3106 *** | 0.4509 *** | 0.4336 *** | 0.4340 *** | 0.4183 *** | ||

| (0.0495) | (0.0471) | (0.0481) | (0.0480) | (0.0456) | |||

| BPR × SCI | 0.2188 *** | 0.2169 *** | 0.2283 *** | 0.2371 *** | |||

| (0.0282) | (0.0281) | (0.0286) | (0.0272) | ||||

| IS | 0.0958 * | 0.0270 | 0.0907 | ||||

| (0.0575) | (0.0751) | (0.0724) | |||||

| BPR×IS | 0.0148 | 0.0929 *** | |||||

| (0.0308) | (0.0333) | ||||||

| SCI × IS | −0.0768 ** | 0.0167 | |||||

| (0.0308) | (0.0350) | ||||||

| BPR × SCI × IS | 0.0710 *** | ||||||

| (0.0146) | |||||||

| DOIS | 0.1927 *** | ||||||

| (0.0636) | |||||||

| Constant | 4.6895 *** | 2.3367 *** | 0.7470 | 0.4946 | 0.8110 | 0.5433 | 2.5838 *** |

| (0.3899) | (0.4618) | (0.4548) | (0.4775) | (0.5336) | (0.5086) | (0.4629) | |

| N | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.1139 | 0.3287 | 0.4809 | 0.4854 | 0.4961 | 0.5475 | 0.0225 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fei, L.-G.; Liu, X.; Jin, Y.-C.; Su, M. Reconstruction of Logistics Services in Cross-Border E-Commerce and Consumer Continuance Intention on Platforms: The Mediating Role of Digital Logistics Services. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030251

Fei L-G, Liu X, Jin Y-C, Su M. Reconstruction of Logistics Services in Cross-Border E-Commerce and Consumer Continuance Intention on Platforms: The Mediating Role of Digital Logistics Services. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2025; 20(3):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030251

Chicago/Turabian StyleFei, Liu-Gao, Xin Liu, Yu-Ci Jin, and Miao Su. 2025. "Reconstruction of Logistics Services in Cross-Border E-Commerce and Consumer Continuance Intention on Platforms: The Mediating Role of Digital Logistics Services" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 20, no. 3: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030251

APA StyleFei, L.-G., Liu, X., Jin, Y.-C., & Su, M. (2025). Reconstruction of Logistics Services in Cross-Border E-Commerce and Consumer Continuance Intention on Platforms: The Mediating Role of Digital Logistics Services. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(3), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20030251