1. Introduction

Online healthcare platforms (OHPs) have developed rapidly in recent years. They pool medical resources from different hospitals at various levels, offering patients the opportunity to access high-level doctors nationwide [

1]. The patients can easily consult their desired doctors in terms of a series of paid services, including text-based, video, and voice consultations [

2]. Normally, the consultation fee ranges between 10 and 300 yuan per consultation. Aside from the paid services, free services that OHPs provide include knowledge sharing [

3]. Such services enable patients to research before deciding on their health. Usually, a patient would go through a doctor’s profile before visiting them; this includes the expertise of such doctors, the ranking of the hospital in that particular field of medicine, and the doctor’s specialty [

4].

Knowledge sharing has been one of the most prominent services featured on physicians’ profiles and has also been widely discussed in the literature on OHPs. It is typically offered by physicians, nursing staff, and various other healthcare practitioners who are dedicated to the distribution of medical information [

3]. The objective is to establish a virtual community that enables patients to gain a clearer comprehension of their health issues, simultaneously fostering reciprocal learning among healthcare professionals [

5]. The exchange of knowledge not only bolsters patient trust but also facilitates informed decision-making concerning healthcare among patients [

6]. This boosts engagement on the platform and raises the number of consultations [

7]. The literature has already extensively discussed the importance of knowledge sharing in attracting patients and impacting their consulting behavior.

Knowledge sharing is mostly treated as a form of prosocial behavior [

8,

9]. Prosocial behavior involves both altruistic and egoistic motivations [

10]. Altruism refers to acts that mostly benefit other people, while egoism involves acts that benefit the actor and other people [

11]. Prior research indicates that knowledge sharing between doctors and patients fosters mutual trust, helps build credibility, and raises the professional profile. All these positive outcomes eventually attract more patients and bring improved financial returns [

3,

12]. On the other hand, pros for patients in an altruistic sense encompass a better understanding of one’s health condition through medical knowledge gained, empowerment to make informed choices, and lessened asymmetry of information, which prevails between the caregiver and the patients [

13]. While previous research has largely focused on the altruistic dimensions of knowledge sharing with patients, there has been a relative neglect of the ways in which physicians’ prosocial behaviors may impact their colleagues within the same medical specialty or institution. This paper tries to fill this gap by bringing to the forefront the altruistic aspects of knowledge sharing and exploring its subsequent effects on other physicians.

Previous spillover effects studies have mainly addressed the domain of consumer behavior, where experiences with one product influenced decisions related to other products within the same brand [

14]. Spillover effects, when it comes to competitors, typically explored in consumer behavior, have been mainly focused on the negative impacts, such as how a crisis can affect the financial value of competitors [

15,

16]. However, in the case of healthcare, spillover effects can extend beyond these negative impacts, potentially fostering a more cooperative environment. In the context of OHPs, the spillover effect goes further than the individual consultations of the doctor; it refers to the potential for one doctor’s knowledge sharing to spill over into the consultations of other doctors within the same specialty or hospital. This phenomenon has not been fully explored in OHPs, especially in prosocial behavior. By investigating the spillover effects of knowledge sharing, this paper extends the scope of prosocial altruism from individual physicians to their colleagues in the broader healthcare ecosystem. Given this background, the current study attempts to answer the following fundamental research questions:

Q1: Does a doctor’s knowledge sharing increase the number of paid consultations for other doctors in the same specialty on OHP?

Q2: Does a doctor’s knowledge sharing increase the number of paid consultations for other doctors in the same offline hospital?

In addition, this study examines how the spillover effects of physicians’ knowledge sharing are conditioned by a range of individual-level and contextual factors. At the individual level, physician characteristics such as online popularity, consultation price, professional title, and gender may influence how patients perceive and process information, thereby moderating the extent to which knowledge sharing leads to spillover effects. At the contextual level, institutional and environmental attributes—including specialty type, hospital level, consultation responsiveness (as proxied by wait time), and the economic development level of the hospital’s province—may also shape the diffusion of trust and information. These dimensions reflect both the personal traits of the physician and the broader structural conditions under which medical knowledge is shared and interpreted.

We therefore explore the following research questions:

Q3: How are these spillover effects moderated by physician-level characteristics, such as popularity, consultation price, professional title, and gender?

Q4: How do contextual and institutional factors—including specialty type, hospital level, consultation responsiveness, and the regional economic environment—condition the magnitude of the spillover effects?

This paper empirically investigates the spillover effects of physicians’ prosocial behavior, specifically knowledge sharing, on online healthcare platforms. Our findings indicate that, besides helping patients, such prosocial behavior exerts a strong influence on the paid consultations of other physicians within the same specialty and offline hospital. More importantly, the magnitude of these spillover effects varies systematically across both physician-level characteristics and contextual factors. Stronger spillover effects are observed among physicians in tertiary hospitals and in specialties such as obstetrics and gynecology, as well as among those with distinct individual traits such as high reputation or junior title—reflecting the complex interplay between organizational position, individual visibility, and contextual receptiveness. These findings highlight the importance of knowledge sharing as a prosocial behavior that can enhance cooperation and mutual learning among healthcare professionals, leading to improved patient outcomes and increased platform engagement.

This study contributes to theory in several ways. First, it extends our understanding of prosocial behavior by examining its indirect effects on the healthcare ecosystem. While previous studies have emphasized the direct benefits of prosocial behavior for either patients or individual physicians, this research highlights its role in creating a reciprocal benefit for other physicians in the same network and thus fills an important gap in the current literature. Second, the study advances the theoretical understanding of spillover effect heterogeneity by jointly analyzing how both physician-level characteristics (e.g., popularity, price, title) and institutional factors (e.g., specialty, hospital level, responsiveness, regional GDP) moderate the strength and direction of these effects. The findings highlight the contextual features of prosocial behavior, which may have very different effects depending on both individual and situational factors. Third, the study contributes to understanding the interdependence between digital and physical healthcare systems, showing that online altruistic behavior can generate tangible benefits within offline hospital environments through increased trust diffusion and brand alignment.

3. Research Hypothesis

This study examines the impact of physicians’ altruistic behavior, specifically knowledge sharing, on the paid consultations of other physicians in the same specialty group or offline medical facility on online health platforms (OHPs). We focus on how physicians’ prosocial behaviors, such as sharing medical knowledge, influence the paid consultations of other physicians in the same specialties or medical facilities. Furthermore, the extent and direction of these spillover effects may not be uniform. Drawing from the literature on digital reputation, healthcare decision-making, and institutional dynamics, we propose that both individual-level characteristics (e.g., popularity, price, professional title, and gender) and contextual factors (e.g., specialty type, hospital tier, consultation responsiveness, and regional socioeconomic environment) moderate the strength of these effects.

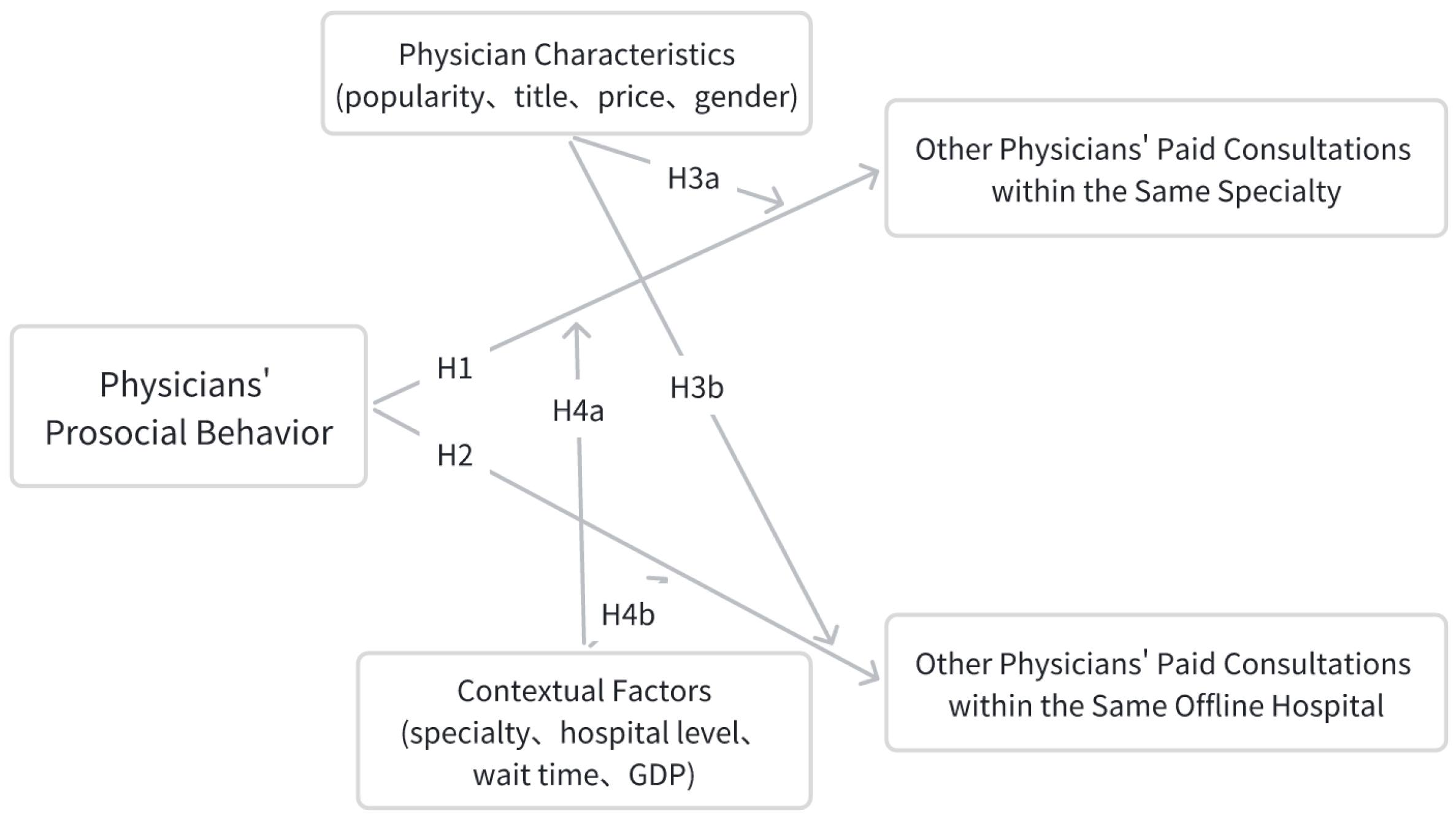

Figure 1 presents the conceptual framework guiding our hypotheses.

3.1. Impact of a Physician’s Prosocial Behavior on Paid Consultations Within the Same Specialty

Previous studies have shown that physicians’ prosocial behavior, such as sharing medical knowledge, results in more patient trust, which consequently increases consultations for the physician exhibiting this behavior. However, a physician’s prosocial behavior may also have broader effects. In the case of OHPs, prosocial behavior may not only affect the individual physician but also spill over to affect consultations of other physicians in the same specialty. This occurs because those who come into contact with the collective knowledge of a certain doctor may develop a higher level of trust in the specialty in general, leading them to seek the consults of other doctors within the same field.

H1: Physicians’ prosocial behavior increases the number of paid consultations for other physicians within the same specialty group on OHP.

3.2. Impact of a Physician’s Prosocial Behavior on Paid Consultations Within the Same Offline Hospital

Similarly, knowledge sharing by physicians within an OHP can spill over to affect the consultations of physicians at the same offline hospital. Engaging a physician’s shared knowledge may make the patients more trustful of the whole healthcare institution so as to make them visit other physicians also in the hospital for consultations. This spillover effect occurs as the patients’ perceptions of the hospital’s competence are influenced by the information given by the individual physicians, thus increasing consultations for other physicians within the same institution.

H2: Physicians’ prosocial behavior leads to increased paid consultations for other physicians within the same offline hospital on OHP.

3.3. Moderating Effect of Physician Characteristics

Individual physician attributes may condition how knowledge-sharing behavior produces spillover effects. Characteristics such as online popularity, consultation price, professional title, and gender influence patient perceptions, information processing, and decision-making. These characteristics can either amplify the reach of knowledge-based trust, constrain its diffusion, or alter the underlying mechanisms through which trust is transferred. Accordingly, the spillover effects of prosocial behavior may vary across physicians within the same specialty group or within the same offline hospital, depending on these individual-level factors.

H3a: The spillover effect of physicians’ prosocial behavior within the same specialty group is moderated by physician-level characteristics (i.e., popularity, price, title, and gender).

H3b: The spillover effect of physicians’ prosocial behavior within the same offline hospital is moderated by physician-level characteristics (i.e., popularity, price, title, and gender).

3.4. Moderating Effect of Medical Context and Environment

Beyond individual attributes, contextual and institutional factors such as specialty type, hospital level, consultation responsiveness (proxied by wait time), and regional economic environment may influence how prosocial behavior spreads. These factors shape the structure of medical collaboration, visibility of information, patient expectations, and the perceived credibility of medical collectives.

H4a: The spillover effect of physicians’ prosocial behavior within the same specialty group is moderated by medical context (i.e., specialty type, hospital level, consultation responsiveness, and regional GDP).

H4b: The spillover effect of physicians’ prosocial behavior within the same offline hospital is moderated by medical context (i.e., specialty type, hospital level, consultation responsiveness, and regional GDP).

Based on these hypotheses, the present study aims to extend our understanding of the spillover effects of prosocial behavior in the context of OHPs. Specifically, we investigate not only whether physicians’ prosocial behavior generates spillover effects across organizational boundaries—within the same specialty and offline hospital—but also how individual attributes and contextual factors condition the magnitude and direction of these effects. This layered hypothesis framework builds upon existing literature while reflecting the multifaceted heterogeneity inherent in platform-mediated medical interactions.

6. Discussion

6.1. Key Findings

This study investigates the spillover effects of physicians’ prosocial behavior—specifically knowledge sharing—on the paid consultations of their peers within the same specialty group and the same offline hospital on an online healthcare platform (OHP). The findings provide strong empirical support for the presence of positive and statistically significant spillover effects, consistent with Hypotheses 1 and 2. Notably, the spillover effect is substantially larger within offline hospitals compared with within specialty groups. This difference suggests that the influence of knowledge sharing is more pronounced in hospital-level networks, where brand synergy and resource integration amplify patients’ collective trust and facilitate broader diffusion of shared information across departments.

Beyond the confirmation of main effects, this study contributes a systematic investigation of spillover heterogeneity across two dimensions: (1) individual physician attributes (e.g., popularity, price, title, and gender) and (2) contextual/institutional characteristics (e.g., specialty type, hospital level, consultation responsiveness, and regional GDP). These multidimensional subgroup analyses reveal that the pathways and strength of spillover effects vary significantly across different contexts.

At the individual level, physician popularity moderates the direction and magnitude of spillover in distinct ways. Within specialty groups, less popular physicians exhibit stronger spillovers due to their high-frequency sharing behavior that bridges information gaps and enhances departmental trust. In contrast, within hospitals, highly popular physicians produce stronger effects, likely due to their reputational capital acting as a trust anchor that diffuses confidence throughout the institutional brand. Physician title exhibits a reverse pattern: junior physicians generate larger spillovers within specialty groups, while senior physicians dominate at the hospital level. This divergence reflects how visibility, authority, and organizational anchoring condition the influence of knowledge-sharing behavior.

In terms of contextual heterogeneity, spillover effects are stronger in pediatrics, traditional Chinese medicine, and obstetrics and gynecology within specialty groups, highlighting the importance of collective trust and long-term engagement in patient decision-making. Conversely, at the hospital level, the strongest effect emerges in obstetrics and gynecology, while pediatrics exhibits a negative spillover—due to internal resource competition. Hospital level also matters: tertiary hospitals consistently show stronger spillovers, reaffirming the role of platform-enabled brand integration and horizontal collaboration. Additionally, while regional GDP moderates specialty-level spillovers, its influence is less evident at the hospital level, underscoring how institutional structures can mitigate regional disparities in healthcare access and trust formation.

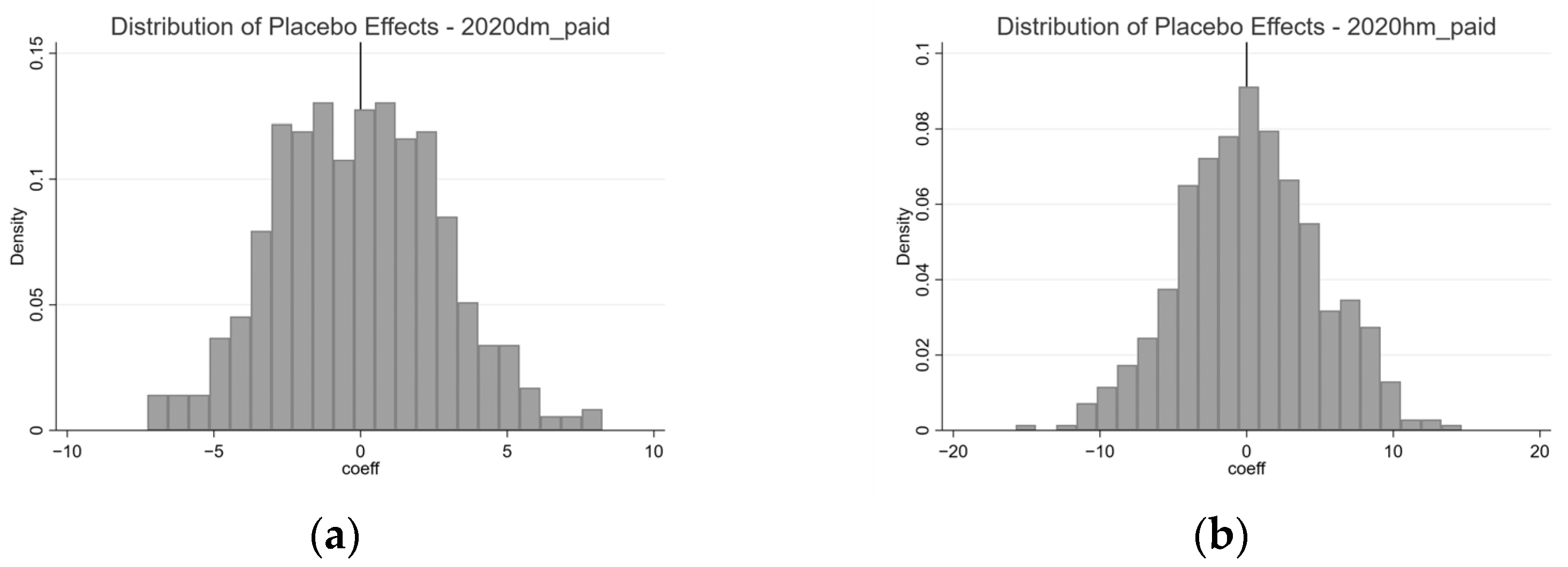

Robustness checks, including alternative caliper widths, multistage sampling, year-specific subsamples, and inverse probability weighting (IPW) models, further support the validity of these findings. Across all methods, knowledge-sharing spillovers remain statistically significant and directionally consistent, with hospital-level effects consistently stronger. These robustness tests affirm the causal interpretation and reliability of the results across diverse empirical specifications. Moreover, the robustness of these findings is further supported by sensitivity and placebo analyses.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study makes several important contributions to the literature. First, it extends the understanding of prosocial behavior by investigating its indirect effects within the ecosystem of healthcare. While prior work has focused almost exclusively on the direct benefits of prosocial behavior for patients or individual physicians [

9,

57], this study highlights its ability to generate reciprocal benefits for other physicians in the same network, thus filling a key gap in extant research.

The results contribute to the theoretical framework of spillover effect heterogeneity by distinguishing between physician-level and institutional-level moderators. Prior studies have often treated heterogeneity in isolation—focusing on single characteristics such as specialty or title—but this research adopts an integrative approach to jointly analyze how individual attributes and organizational context shape the strength, scope, and direction of spillover effects. The findings reveal that the same physician behavior may operate through different mechanisms depending on the surrounding institutional environment, offering a richer theoretical account of how prosocial actions propagate through complex systems.

This study contributes to the understanding of the interplay between online and traditional healthcare systems. It shows how online prosocial behavior can benefit hospital-wide visibility, trust coordination, and peer collaboration, thus underlining the interdependent nature of modern healthcare ecosystems.

6.3. Practical Implications

The findings offer actionable insights for OHPs, healthcare administrators, and policymakers. First, platforms can actively promote a culture of prosocial behavior by emphasizing its collective benefits. For platforms, promoting knowledge sharing can enhance not only individual physician visibility but also system-wide engagement and patient trust. Importantly, incentive schemes should account for the observed heterogeneity: encouraging junior and less popular physicians to share content can strengthen specialty-level collaboration while leveraging the reputational capital of senior physicians enhances hospital-level diffusion.

Second, hospitals should integrate digital knowledge-sharing practices into their branding and trust-building strategies. Tertiary hospitals, in particular, stand to benefit from supporting high-profile physicians in content production, thereby reinforcing institutional credibility and patient engagement. Additionally, specialties such as obstetrics and gynecology, where spillovers are strong, may be prioritized in campaigns that promote digital outreach.

Lastly, policy frameworks should recognize prosocial behavior as a public good in healthcare ecosystems. By designing policies that reward information sharing and reduce structural barriers to trust diffusion, regulators can foster a more transparent, equitable, and patient-centered care environment.

6.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has certain limitations related to the availability of data from OHPs. While we have extended the research on spillover effects to include physicians within the same offline hospital, the inability to access additional offline hospital data for these patients limits the scope of our analysis. For example, data on patients’ offline interactions with other physicians, their referral pathways, or their longitudinal healthcare engagement would provide a more comprehensive understanding of spillover dynamics across online and offline systems.

Future research could replicate this study across different online healthcare platforms or international contexts to test the robustness of the findings in varied institutional environments. Additionally, employing more advanced causal inference techniques—such as instrumental variable approaches or longitudinal panel designs—would allow for a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of prosocial behavior. Further exploration of heterogeneous forms of prosocial engagement, including peer recommendations, interactive Q&A, or multi-physician collaborations, could provide nuanced insights into trust dynamics and platform engagement mechanisms.