Abstract

Information asymmetry between manufacturers and online retailers regarding consumer preferences for store brands profoundly influences operational strategy. By leveraging information technology, online retailers can collect valuable consumer data, creating a strategic dilemma: whether to share this information with manufacturers and, if so, with which manufacturer (national or third-party). This study aims to explore an online retailer’s strategic decisions regarding sharing information with manufacturers, filling a gap in the literature on store brands and consumer preferences. Using game theory, we analyze the interactions among an online retailer, a national manufacturer, and a third-party manufacturer, incorporating the Hotelling model to capture consumer preference and product differentiation. Our findings reveal that information sharing does not consistently benefit the online retailer or manufacturers. Notably, without side payment, the online retailer is unwilling to share information with either manufacturer, and manufacturers do not always gain more from receiving such information—a result that challenges conventional wisdom. However, when side payment is introduced, the online retailer’s willingness to share information depends on key factors: the probability of low brand loyalty (low-type) consumers, the proportion of comparison shoppers, the side payment, and the degree of information uncertainty. These findings provide innovative insights for operations managers, highlighting the critical role of information management in shaping strategic decisions and enhancing the efficacy and financial outcomes of information sharing in the context of store brands.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of the online retail sector has positioned store brands as a pivotal element in redefining market competition dynamics [1,2,3]. This phenomenon is largely driven by the retailer’s ability to leverage consumer preference information, which enables them to design products that precisely meet consumer needs. According to Forbes, sales of store brands in the US reached nearly USD 200 billion in 2022, accounting for 19.6% of all groceries sold [4]. Following this trend, online retailers, such as JD and Amazon, have launched their store brands to better align with consumer preferences [5]. For instance, Amazon introduced its store brands as early as 2009, and its store brands, such as Amazon Basics and Pinzon, ranked among the top 10 most popular names. These brands collectively contribute to approximately 81% of all sales [6]. Similarly, JD introduced its store brand J. ZAO in January 2018, further demonstrating the strategic importance of store brands in driving retail innovation and market success [7].

Online retailers increasingly introduce store brands, yet consumer preference for these brands varies widely. Typically, store brands are positioned as economical substitutes for national brands but are frequently regarded as lower in quality owing to their production by third-party manufacturers at reduced costs. For example, due to the higher consumer preference for Coca-Cola, Walmart’s introduction of Sam Cola is intended to appeal to price-conscious consumers through a reduction in prices. However, a recent trend shows online retailers launching premium store brands that rival national brands in quality. A notable example is Tesco’s “Tesco Finest” line, developed in collaboration with renowned chefs to offer high-end ready-to-eat dishes such as fish escalopes with Prosecco dressing and vegetable dauphinoise with premium meats [8]. The introduction of such premium store brands can significantly boost consumer willingness to pay, thereby increasing the acceptance of store brands. This evolution underscores the importance of strategic store brand management and the potential for technological innovations to reshape consumer perceptions and behaviors in the retail sector.

Additionally, the most significant challenge in online retailing concerns asymmetrical information between manufacturers and online retailers, particularly amidst highly diverse consumer preferences for store brands. Online retailers, empowered by information technology, can gather data on consumer preferences regarding store brands [9]. This wealth of data provides valuable insights into evolving consumer behavior and preference [10], enabling online retailers to strategically develop and tailor their store brands to align with market demands [11,12]. In contrast, manufacturers often lack comprehensive information on consumer preferences regarding store brands, impeding effective demand monitoring and pricing, thus relying heavily on online retailers to acquire this information. For example, after realizing the importance of this information, JD implemented large-scale data technology to assist manufacturers in gaining a deeper understanding of consumer behavior. Similarly, Amazon employed information technology to efficiently transfer consumer information to its principal manufacturers [13]. Consequently, the effective integration of information technology management is crucial for online retailers aiming to navigate and capitalize on the dynamic landscape of store brands.

Motivated by these observations, this study aims to answer the following important issues. How does information asymmetry affect the online retailer’s sale prices and the manufacturers’ wholesale prices for the national brand and store brand? Is there any motivation for an online retailer to share consumer information with manufacturers? And, if yes, is this with the national manufacturer or the third-party manufacturer? Which factor will affect the online retailer’s information-sharing strategy?

To address these inquiries, we have established a distribution channel model wherein an online retailer markets both a national brand (sourced from a national manufacturer) and a store brand (sourced from a third-party manufacturer) to end consumers. Notably, consumer preference for the store brand varies significantly, ranging from low to high acceptance levels. Leveraging IT technology, the online retailer privately observes actual consumer preference for store brands, while manufacturers maintain their assumptions about this information. The online retailer makes an ex ante decision on whether to share this valuable consumer information with manufacturers, leading to four distinct information-sharing strategies: (1) ‘no information sharing’ (Scenario NN), where the online retailer shares no information with either manufacturer; (2) ‘full information sharing’ (Scenario II), where the online retailer shares consumer preference information with both manufacturers; (3) ‘information sharing with the national manufacturer only’ (Scenario IN); and (4) ‘information sharing with the third-party manufacturer only’ (Scenario NI). Our model first derives the equilibrium prices for each game player under these four scenarios. Subsequently, by comparing profits across different scenarios, we identify the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy and analyze the impact of key parameters such as the probability of low brand loyalty (low-type) consumers, the proportion of comparison shoppers, the side payment, and the degree of information uncertainty regarding the outcomes.

This paper employs game theory in conjunction with the Hotelling model. Game theory, which captures the interactive decisions of multiple decision-makers, has been extensively applied in supply chain management literature to model decision-making dynamics among supply chain partners [1,2,3,11,12]. The Hotelling model offers a spatial competition framework that is particularly well-suited for examining product differentiation and consumer preference within a competitive market context [14,15]. By integrating the two theoretical frameworks, this study examines how the online retailer’s information-sharing strategy influences the interactions among the national manufacturer, the third-party manufacturer, and the online retailer. Furthermore, the Hotelling model’s focus on spatial differentiation provides a framework for analyzing how consumer preference for store brands is influenced by product positioning and competitive interactions. This theoretical underpinning facilitates an examination of how an online retailer’s information-sharing decisions impact pricing strategies, market competition dynamics, and overall supply chain efficiency.

The results can be summarized as follows. First, our findings highlight key factors influencing the online retailer’s strategy selection, including the probability of consumers being low-type purchasers, the proportion of comparison shoppers, the side payment, and the degree of information uncertainty. Notably, without side payment, the online retailer is hesitant to share information with manufacturers, while manufacturers do not always derive significant benefits from obtaining such information. Second, an increased likelihood of consumers being low-type purchasers does not reliably encourage information sharing by the online retailer, whereas a greater proportion of comparison shoppers (information uncertainty) restrains (motivates) information-sharing decisions. These findings have substantial implications for the online retailer in developing an optimal information-sharing strategy, highlighting the essential role of information management in facilitating effective decision-making and performance optimization in the dynamic online retail industry.

We contribute to the store brand literature in the following two respects. First, we focus on consumer preference for store brands, rather than product-related information, such as cost [16], supplier [17], or potential demand [18]. By classifying consumers into low-type and high-type purchasers based on their preferences for store brands, we develop a novel market demand function using the Hotelling model. This function integrates horizontal differentiation (product–consumer fitness) and vertical differentiation (consumers’ perceived quality level of the store brand), offering a more nuanced understanding of market dynamics compared to previous studies. Second, we extend the literature on information sharing by exploring whether an online retailer should share private information with the national manufacturer, the third-party manufacturer, or both. Using an information strategy matrix, we analyze the impact of information sharing on store brand operations. Our model incorporates key factors such as the probability of low-type consumers, the proportion of comparison shoppers, the side payment, and the degree of information uncertainty, providing new insights into when and how information sharing is beneficial. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate an information strategy matrix in the context of uncertain consumer preference for store brands. Our findings offer practical guidance for store brand operators on strategic decision-making and the conditions under which sharing information with different manufacturers is advantageous.

The subsequent sections of this paper will be organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature. Section 3 proposes our model setup. The equilibrium outcomes of different strategies are shown in Section 4. Section 5 provides the main results. Section 6 considers an extension, followed by our conclusions in Section 7. Appendix A provides supplementary information regarding the proofs.

2. Literature Review

This research is relevant to the current research in two streams: one stream relates to the operation management of store brands, and the other is about information sharing in e-commerce.

2.1. Store Brands

Our research is part of the growing body of literature that examines the impact of store brands on supply chain operations [19,20]. Early empirical research has shown that (online) retailers experience advantages as a result of offering store brands [21,22,23]. Consistent with those empirical predictions, theoretical research appears to concur that store brands are advantageous for retailers but detrimental for manufacturers [24,25,26]. This phenomenon can be attributed to the competitive pressure exerted by store brands, which compels manufacturers to reduce their wholesale prices, thereby undermining the market dominance of national brands [27,28,29]. Conversely, other research indicates that store brands can benefit manufacturers but may harm retailers [30,31,32].

In a recent study, Li et al. [25] analyze whether to introduce the store brand, taking into consideration the practice of offering both higher- and lower-quality store brand options. According to the findings of Xiao et al. [28], the retailer experiences advantages when the quality level of the store brand surpasses certain thresholds. Katewa and Jain [33] investigate how quality differentiation and price differentiation affect the platform’s investment strategy concerning a co-developed store brand and an existing incumbent product. We extend to an information asymmetry setup whereby the retailer processes private information about consumer preference for store brands, while the national and the third-party manufacturers do not know this information; this is in contrast to previous studies, which focused on symmetric information-setting.

Extensive research has been conducted on the dynamic interplay between asymmetric information and store brands, which is the primary focus of our study. For example, under the assumption that the retailer possesses confidential demand data, Shi and Geng [18] calculate the prerequisites for the retailer to launch store brands in two scenarios: one in which market uncertainty information is shared, and the other in which none is shared. In a similar vein, Hsiao et al. [17] also explore information sharing regarding store brands. Huang et al. [34] examine the incentive for quality information sharing in a supply chain comprising a manufacturer distributing the national brand and a retailer that sells both the manufacturer’s product and its store brand. By contrast, Cao et al. [16] examine a retailer who is more informed and possesses confidential cost data on store brands.

Although related, our study introduces distinct features that advance the store brand literature. Unlike prior research that focuses on cost information [16], demand information [18], supplier information [17], or product quality information [34], we center our analysis on consumer preference information for store brands. By categorizing consumers into low-type and high-type customers, based on their preference for store or national brands, we examine how this classification influences market distributions. Furthermore, we integrate horizontal differentiation (consumer fitness) and vertical differentiation (the perceived quality of store brands) within the Hotelling model to establish a unique market demand function. This framework allows us to derive novel insights into how consumer preferences and information asymmetry shape the retailer’s decision to share information with manufacturers. Additionally, unlike studies that focus on asymmetric information between firms and consumers [17,34], we explore information asymmetry between an online retailer and two manufacturers, providing a fresh perspective on supply chain dynamics. These contributions collectively enhance the theoretical understanding of store brands and their role in supply chain operations.

2.2. Information Sharing

This research also contributes to the expanding corpus of research on information sharing. As a result of operational risk reduction [35,36], participants in the supply chain may experience a boost in earnings as a consequence of information sharing [37]. Jiang et al. [38] conduct a study comparing different types of information sharing: no sharing, voluntary sharing, and compelled sharing, with the involvement of a manufacturer who had greater knowledge. Guan et al. [14] examine the combined decision-making process of obtaining and revealing information in situations where the manufacturer possesses superior-quality knowledge. Zhang et al. [39] demonstrate that encroachment may impede the more knowledgeable manufacturer from disclosing its privacy information. Wang et al. [40] examine the adoption of blockchain technology by the retailer to combat counterfeits and enhance information sharing with the supplier in the context of asymmetric demand and product quality information. Differing from the above papers that focus on a better-informed manufacturer, our study focuses on information sharing by a more knowledgeable online retailer.

Numerous studies have investigated retailers’ strategies for leveraging consumer information [41]. For instance, when the retailer owns private consumer information, Shang et al. [42] analyze its information-sharing decision regarding two rival manufacturers. The study demonstrates that the retailer’s information-sharing decision is influenced by factors such as the non-linear manufacturing cost, the level of competition, and the information fee. Li et al. [43] analyze the optimal strategy for a retailer in terms of sharing demand information when the manufacturer supplies both its own outlets and those of the retailer. However, these studies primarily focus on information sharing within traditional supply-chain frameworks.

Furthermore, we expand the research on information strategy by examining whether the online retailer should share its private consumer preference information with both the national and third-party manufacturers. Unlike prior studies that focus on traditional supply chain frameworks or on cost, demand, or quality information [16,38,39], our study uniquely centers on consumer preference information for store brands and its strategic implications. By incorporating key factors such as the probability of low-type consumers, the proportion of comparison shoppers, the production cost, the side payment, and the degree of information uncertainty, our model provides a comprehensive framework for analyzing information-sharing decisions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore an information strategy matrix in the context of uncertain consumer preferences for store brands. Our findings offer novel insights into the strategic decision-making process of store brand operators and identify scenarios in which sharing information with various stakeholders can be advantageous. These contributions advance the supply chain information literature by highlighting the critical role of consumer preference information in shaping supply chain dynamics and decision-making.

3. Model Setup

In this model, we consider an online retailer () that sells products from a national manufacturer () and a third-party manufacturer (). The manufacturer produces the national brand () and sets the wholesale price . Then, the online retailer sells the product with a sales price . Similarly, the online retailer can also introduce a store brand () from manufacturer at and then sell the product with . Assuming that there is no loss in generality, the cost of producing one item by manufacturer is normalized to be zero and the production cost of manufacturer is normalized to be . captures the scenario that manufacturer incurs a greater cost when producing brand than manufacturer when producing brand .

We assume that two distinct categories of consumers exist in the market: loyal consumers, who only consider purchasing product , and comparison shoppers, who will compare the products and and select the one with more utility. Each consumer has a maximum demand of one unit. We normalize the market size of consumers to 1, in which the proportion () of consumers represents comparison shoppers, while the remaining proportion of consumers represents loyal consumers. For the comparison shoppers, given set retail prices of and , the net utilities from purchasing the products and can be given as:

The above utility functions indicate that products in the market may be both horizontally and vertically differentiated [15]. Horizontal differentiation arises as a result of imperfect product–consumer fitness, resulting in misfit costs being borne by consumers, which can be captured with the Hotelling model [44]. In particular, we assume that products and are placed at locations and on a linear scale, along which line consumers are uniformly distributed. The degree of misfit between the consumer and products and are and , respectively, where . Therefore, by purchasing them, the consumer incurs the cost and , respectively.

Vertical differentiation can be attributed to the difference in product quality and the consumer’s valuation of product quality. Let () and represent the consumer’s perceived quality levels of brands and , respectively. For simplicity, we assume without loss of generality. reflects the degree to which consumers see brand as a similar replacement for brand ; it may, thus, be understood as the consumer’s perception of brand ’s quality compared to that of brand [45]. Following the work of Wu et al. [46] and Li et al. [24], we assume to capture the lower consumer preference for brand as compared with brand . We assume the value of the random variable follows a uniform distribution within the intervals and : , with a probability of (), or between and : , with a probability of . This indicates that brand is subject to heterogeneous consumer preferences, which can be categorized into two distinct ranges: the lower-preference range and the higher-preference range . To simplify the calculations, we use 0.5 as the threshold to distinguish between high and low preferences. However, to provide a more comprehensive analysis, we further consider a general threshold in Section 6.1. The results show that the conclusions remain consistent, regardless of the chosen threshold.

Then, for the consumer with () to brand (), the utility difference between the two brands, is:

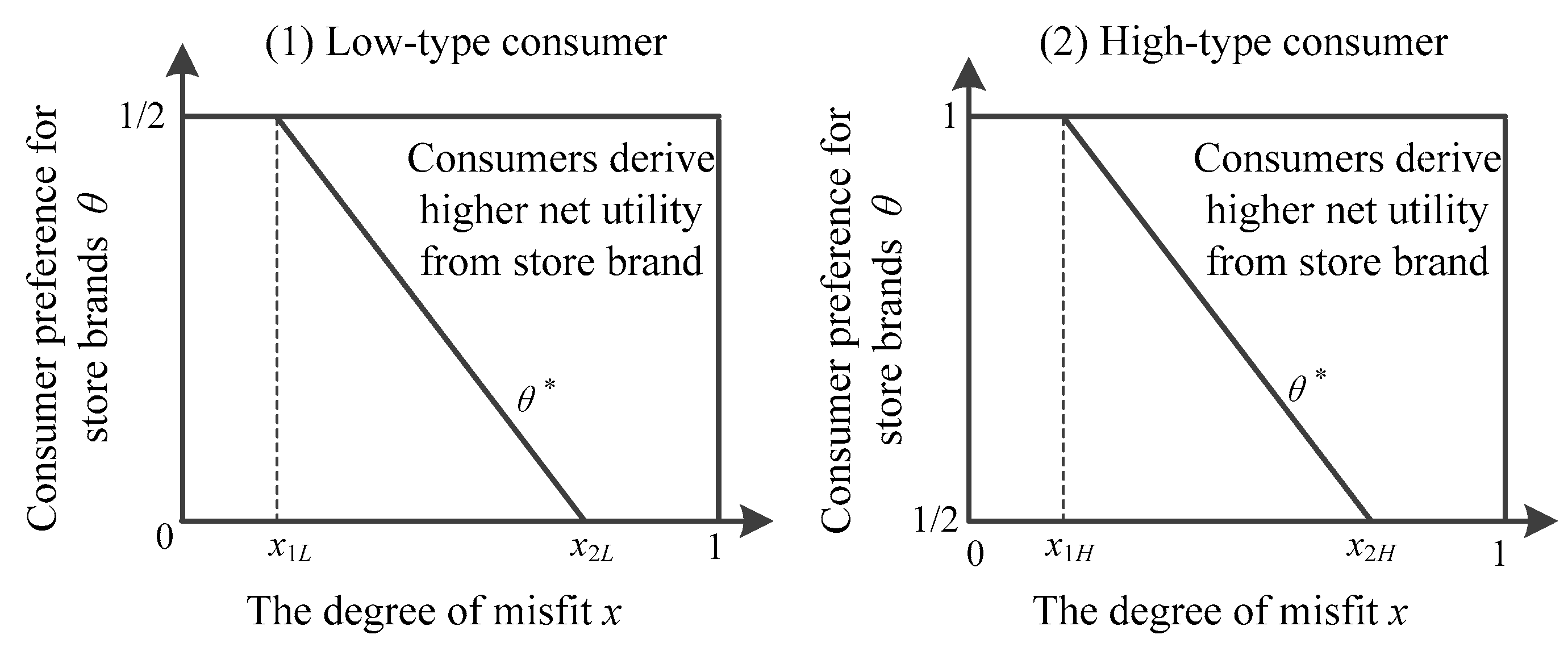

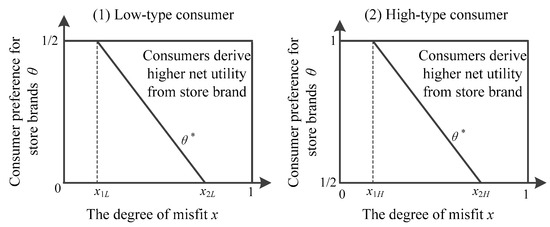

When , we have . Then, as can be seen from Figure 1, with -type consumers, we have and ; with -type consumers, we have and . With loyal consumers, as they are loyal to brand and will not consider brand , they will purchase product as long as .

Figure 1.

Consumer purchase decision.

Therefore, with low-type consumers, we have:

With high-type consumers, we have:

As mentioned above, the online retailer can initially confirm consumer preference by acquiring data. In contrast, manufacturers and only hold an identical preconceived notion about preference, which can be divided into lower preference and higher preference, with equal probability [12,28]. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that the online retailer often possesses sophisticated information technology and data analytics capabilities, hence obtaining more comprehensive insights into customer behavior. Thus, the online retailer uses four kinds of information-sharing strategies: (a) no information sharing (Scenario ), that is, the online retailer shares no information with the manufacturer; (b) full information sharing (Scenario ), that is, the online retailer shares information with both manufacturers; (c) the online retailer only shares information with the national manufacturer (Scenario ); and (d), the online retailer only shares information with the third-party manufacturer (Scenario ).

The game sequence of this model is as follows. First, before assessing the value of consumer preference for brand , the online retailer makes an ex ante decision on information sharing; i.e., whether or not to share such private consumer information with manufacturers, and if yes, to which one. Meanwhile, the online retailer charges a side payment if it shares the information [42]. For example, JD provides a data analytics tool, named JD Business Intelligence (https://dataworks.jd.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2025)), to its manufacturers. When using its advanced functionalities (such as consumer data analysis), the manufacturer has to pay a certain fee to JD. Secondly, after is realized and shared accordingly, the two manufacturers set their wholesale prices and , followed by the online retailer, who sets the retail prices and . All decision variables can be given through profit maximization.

4. Equilibrium

This section analyzes the three game-players’ equilibrium decisions under different information-sharing strategies. To ensure non-negative prices and sales, we limit in the following analysis. The practical significance of this assumption about is that the production cost is relatively small, so the two brands will compete for the same consumers in the end market. Otherwise, a sufficiently large production cost will lead to a sufficient difference in the retail prices of the two brands, thus intensifying price competition [12]. In that situation, consumers tend to purchase products with lower prices, making it difficult for high-cost products to compete in the market.

4.1. Scenario

In Scenario , the online retailer shares information with either manufacturer. According to their preconceived notion of consumer preference, two manufacturers formulate their decisions. The profit functions of three game players can be given by:

The equilibrium results of firms are shown in the following lemma.

Lemma 1.

In Scenario , the optimal wholesale prices are and , leading to retail prices where , , and , respectively.

4.2. Scenario

In Scenario , the online retailer shares information with two manufacturers. It aligns with the real-world situation where the retailer makes its accumulated sales information available on a publicly accessible data platform. Hence, consumer preference for store brands will become common knowledge. The profit functions of firms in Scenario are given as:

The equilibrium results of firms are shown in the following lemma.

Lemma 2.

In Scenario , the optimal wholesale prices are , , , and , leading to retail prices where , , , and , respectively.

4.3. Scenario

In Scenario , the online retailer only shares information with the national manufacturer. The pricing decision of the third-party manufacturer relies on the preconceived notion of consumer preference, while the national manufacturer determines the wholesale price using the shared consumer preference. The profit functions of firms in Scenario are given as:

The equilibrium results for the firms are shown in the following lemma.

Lemma 3.

In Scenario

, the optimal wholesale prices are , , and , leading to retail prices where , , , and , respectively.

4.4. Scenario

In Scenario , the online retailer only shares information with the store manufacturer. Similarly, the national manufacturer makes the pricing decision via its preconceived notion of consumer preference, whereas the third-party manufacturer decides this based on shared consumer preference. The profit functions of firms in Scenario are given as:

The equilibrium results for the firms are shown in the following lemma.

Lemma 4.

In Scenario NI, the optimal wholesale prices are , , and , leading to retail prices where , , and , respectively.

4.5. Market Outcomes

This subsection shows certain market outcomes, such as prices and demands. Propositions 1 and 2 compare the optimal pricing decisions of three game players and the demands of two brands under different information-sharing strategies.

Proposition 1.

By comparing the pricing decisions, we have:

- i.

- and ;

- ii.

- and ;

- iii.

- and ;

- iv.

- and .

We first shed light on the online retailer’s retail prices and the two manufacturers’ wholesale prices. From Proposition 1, we see that the effect of information sharing on optimal wholesale prices varies in the differences between brands and consumer types. Specifically, for brand , we show that information sharing enables manufacturer to charge a higher wholesale price if no information is shared with manufacturer (except for when ), no matter whether the realized consumer type is either low or high. The rationale hinges on the positive effect of information sharing on mitigating uncertain behavior, thus helping manufacturer price their product more accurately.

However, for brand , the effect of information sharing on the wholesale price is different, depending on the realized consumer type. When consumers express a low preference for store brands, Proposition 1(i) shows that information sharing enables manufacturer to charge a higher wholesale price if no information is shared with manufacturer . This is because, with low-type consumers, manufacturer enjoys both brand and information advantages compared with manufacturer , thus charging a higher wholesale price for brand . In contrast, sharing the high-type consumer preference with manufacturer does not always help to raise the wholesale price, no matter whether manufacturer is informed or not, i.e., . This is because sharing a high preference for brand weakens the brand advantage for manufacturer and, thus, intensifies brand competition between the two brands. As a result, manufacturer has to lower the wholesale price to compete with brand .

It is worth noting that higher wholesale prices will boost retail prices for the online retailer. Thus, the impact of information sharing on retail prices is virtually equivalent to that on wholesale prices.

Proposition 2.

Through a comparison of the demands of the two brands, we have:

- i.

- ;

- ii.

- ;

- iii.

- ;

- iv.

- .

Proposition 2 presents the opposite effect of information sharing on the demands of the two brands, depending on the types of consumers. Specifically, when consumers express a low preference for brand , information sharing will decrease the demand for brand (i.e., , where ) but boost the demand for brand (i.e., ). For brand , information sharing leads to a higher retail price, thus deterring consumers from purchasing product , resulting in a decline in its demand. In contrast, awareness of low consumer preference for brand motivates the online retailer to reduce the retail price of brand and boost its demand. Thus, sharing low preference for brand fosters demand for brand while concurrently curbing demand for brand .

The situation is quite the opposite with high-type consumers. As can be seen from Propositions 2(iii) and (iv), when consumers show a high preference for brand , information sharing will assist in enhancing the demand for brand (i.e., ) but, conversely, restrain the demand for brand (i.e., ). This phenomenon arises because, for brand , sharing a high preference for brand heightens the competition between the two brands, inhibiting the online retailer from setting a higher retail price. As a result, consumers are more likely to purchase brand due to its lower retail price. Conversely, this information discourages consumers from purchasing brand , reducing its demand. While information sharing strengthens the competitive position of manufacturer , allowing them to raise the wholesale price, the subsequent increase in the retail price adversely affects demand for brand .

5. Discussion

5.1. Information Sharing Without Side Payment

Proposition 3.

Without side payment (), the third-party (national) manufacturer benefits from receiving information from the online retailer if the national (third-party) manufacturer is (not) informed, i.e., and . In contrast, the third-party (national) manufacturer does not always benefit from receiving information from the retailer if the national (third-party) manufacturer is not informed, i.e., and does not always hold.

Proposition 3 presents a noteworthy finding that challenges the prevailing beliefs. Prior research revealed that without the side payment, both manufacturers benefit from information sharing (Proposition 1(a) of Shang et al. [42]). However, we find that information sharing does not always benefit manufacturers in the context of the consumer’s different preferences for store brands. Specifically, when the national manufacturer is informed, the third-party manufacturer also has the incentive to acquire such consumer information. The rationale hinges on the higher wholesale prices (i.e., and ) and greater demand for brand if consumers are of the low type (i.e., ). However, when the national manufacturer is uninformed, the third-party manufacturer does not always benefit from receiving the online retailer’s information. Although the information advantage enables manufacturer to charge a higher wholesale price (note that and ), the higher retail price may inhibit consumers from purchasing brand if consumers are of the high type. As a result, manufacturer does not always benefit from receiving information from the online retailer if the national manufacturer is not informed.

In contrast, when the third-party manufacturer is not informed, the national manufacturer has the incentive to acquire consumer information, to enjoy both the brand advantage and the information advantage. However, when the third-party manufacturer is informed, the national manufacturer does not always benefit from receiving the retailer’s information. This is because although information sharing can mitigate uncertain behavior and help manufacturer price more accurately, it will intensify the brand competition between the two products. As a result, the national manufacturer may, conversely, gain more benefits from not acquiring such consumer information.

Such a finding enriches the existing literature on the impact of information sharing on uninformed manufacturers, one that has important implications for manufacturers regarding whether or not to acquire information regarding consumer preferences for store brands. Therefore, even if there is no cost to investing in information infrastructure, e.g., a shared database [47], the manufacturer has to think twice about whether to reach an agreement on information sharing.

Proposition 4.

Without side payment (), the online retailer will not share any information with either manufacturer.

The above result is in line with the literature [43]. This is because not sharing the low-type consumer preference with either manufacturer has the potential to induce manufacturer to set the lowest wholesale price of the national brand, thereby enlarging the sales of this brand (see Proposition 1(i) and Proposition 2(i)). For the store brand, the online retailer will set the highest sales price to squeeze out a larger marginal profit, although doing so will lead to the smallest sales for this brand. In contrast, when consumers are of the high type, then not sharing information with either manufacturer has the potential to induce manufacturer to set the lowest wholesale price for the store brand, thereby enlarging the sales of this brand (see Proposition 1(iv) and Proposition 2(iv)). For the national brand, the online retailer will set the highest sales price to squeeze out a larger marginal profit, although doing so will lead to the smallest sales numbers for this brand. Nevertheless, the online retailer still benefits from the highest total profit by selling the two brands under Scenario NN, especially when sharing its private consumer information with the manufacturer cannot bring additional profit (i.e., ).

5.2. Information Sharing with Side Payment

We then consider the situation in which manufacturers must pay the online retailer a side payment to acquire information, i.e., . The findings are summarized in the subsequent propositions.

Proposition 5.

With a side payment (), neither the third-party manufacturer nor the national manufacturer will always benefit from receiving information from the online retailer, no matter whether the rival is informed or not, i.e., and does not always hold when .

As compared with the findings revealed in Proposition 3, Proposition 5 shows different findings regarding the effect of information sharing on the profitability of manufacturers. The rationale hinges on the side payment. When the advantage of receiving information cannot offset the disadvantage of side payment, the manufacturer may react negatively to receiving such information.

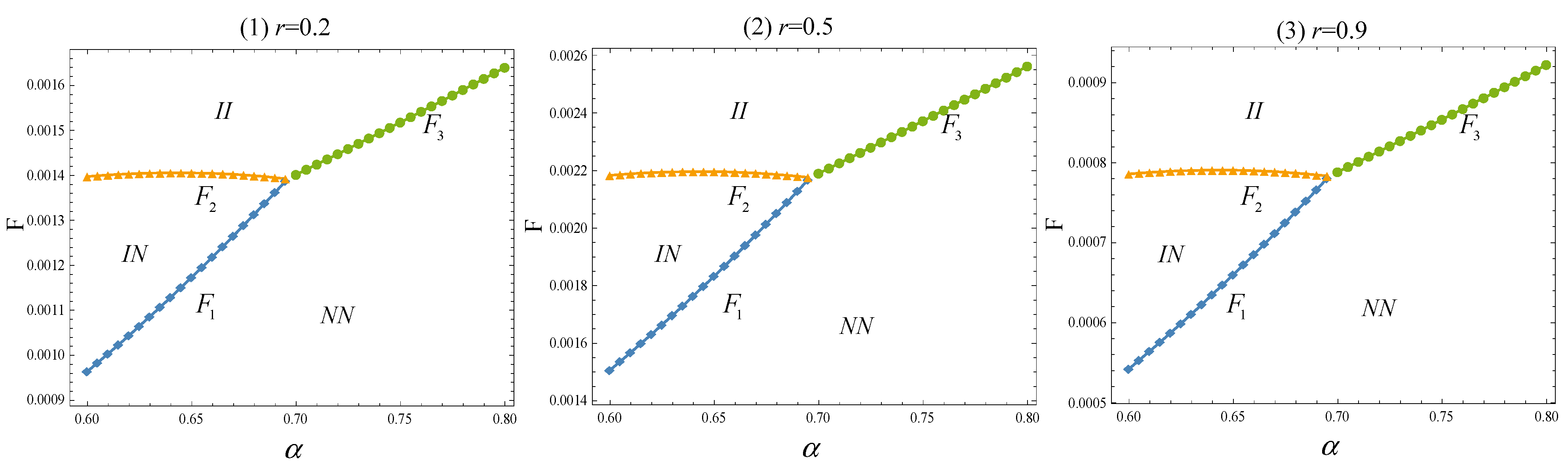

Proposition 6.

With a side payment (), thresholds , , , and exist, such that:

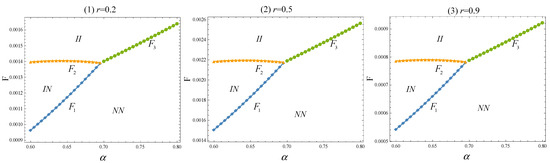

(1) when , the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy is NN if , then shifts to IN if , and finally, to II if ; (2) when , the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy is NN if , then it shifts to II if where , , , and .

Proposition 6, as also illustrated in Figure 2, shows that the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy will be affected by three model parameters: the probability of which consumers are of the low type (), the proportion of comparison shoppers (), and the side payment (). Specifically, when the proportion of comparison shoppers is below a set threshold (i.e., ), a comparatively low side payment will still inhibit the online retailer from sharing private consumer information with either manufacturer. The rationale is quite similar to the case when . In contrast, a sufficiently high side payment (i.e., ) stimulates the online retailer to share information with both manufacturers, due to the dominant effect of the side payment.

Figure 2.

The online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy.

More interestingly, with a moderate , i.e., , the online retailer prefers to share information solely with manufacturer rather than with manufacturer . The rationale is as follows. As stated in Proposition 1, sharing high-type consumer preferences solely with manufacturer rather than with manufacturer can induce both manufacturers to lower the wholesale prices of the two brands (i.e., and ), thereby enlarging the sales of the two brands (i.e., and ). Although sharing low-type consumer preferences solely with manufacturer has the potential to induce the manufacturer to lower the wholesale price, thereby leading to smaller sales of the two brands, it turns out the total payoff, including two types of consumers, under Scenario IN is larger than that under Scenario NI. As a result, a moderate side payment stimulates the online retailer to share its private consumer information solely with the manufacturer . When consumers are more likely to be shoppers (i.e., ), the online retailer will not share information with either manufacturer (Scenario ) due to a low side payment (i.e., ), or it will share information with both manufacturers (Scenario ) when the side payment exceeds a threshold (i.e., ).

Corollary 1.

(1) Threshold () increases in if and decreases in otherwise. As a result, a larger does not always induce the online retailer to share its private consumer information. (2) and always increase in , while increases in if and decreases in if , where . As a result, a larger does not always induce the online retailer to share its private consumer information.

As one might expect, a larger value has the potential to inhibit the online retailer from sharing information with the manufacturer; both Figure 2 and Corollary 1 reveal that a larger may conversely stimulate the online retailer to share information with the manufacturer. As can be seen from Figure 2 for the fixed values of and (taking and as an example), the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy switches from with a small (e.g., ) to with a moderate (e.g., ), and finally to when the value for is large enough (e.g., ).

Additionally, although the online retailer’s payoff under these four scenarios is always increasing in , the effect under Scenario is more pronounced than that under other scenarios (e.g., Scenario and Scenario ). Therefore, as increases, the online retailer becomes more reluctant to share its private information with the manufacturer.

6. Extensions

6.1. A General Point Between the Low and High Preferences

In the basic model, we use the uniformly distributed mean, i.e., 0.5, as the point to divide the high and low preferences. In this section, we consider a general point to divide the low and high preferences. Specifically, we assume that follows a uniform distribution within the intervals and : with a probability of , or between and : with a probability of , where . Then, given , , , and , the demand functions of two types of consumers are:

Proposition 7.

By considering a general point between the low and high preferences, we find that the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy is consistent with the basic model.

Although the point between the low and high preferences will impact the demand functions and, thus, the pricing decisions, as well as the profit of the online retailer, Proposition 7 shows that this chosen point will not impact the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy.

6.2. Consumer Preference Overlap

In the basic model, we assume that the consumer preference toward store brands falls into two independent regions. In this section, we extend the model to consider a more complicated case in which there is overlap between the two regions. To this end, we assume that the value of the random variable follows a uniform distribution within the intervals and : with a probability of (), or between and : with a probability of . measures the degree to which two regions of consumers overlap, and the larger is, the smaller the difference between the two types of consumers, and the greater the degree of information uncertainty will be. This market overlap can be attributed to information uncertainty. Put differently, even after observing a specific value of consumer preference toward store brands, this seems still to be somewhat uncertain for the online retailer regarding the type of consumer.

Therefore, given that , , , and , the demand functions of the two types of consumers are:

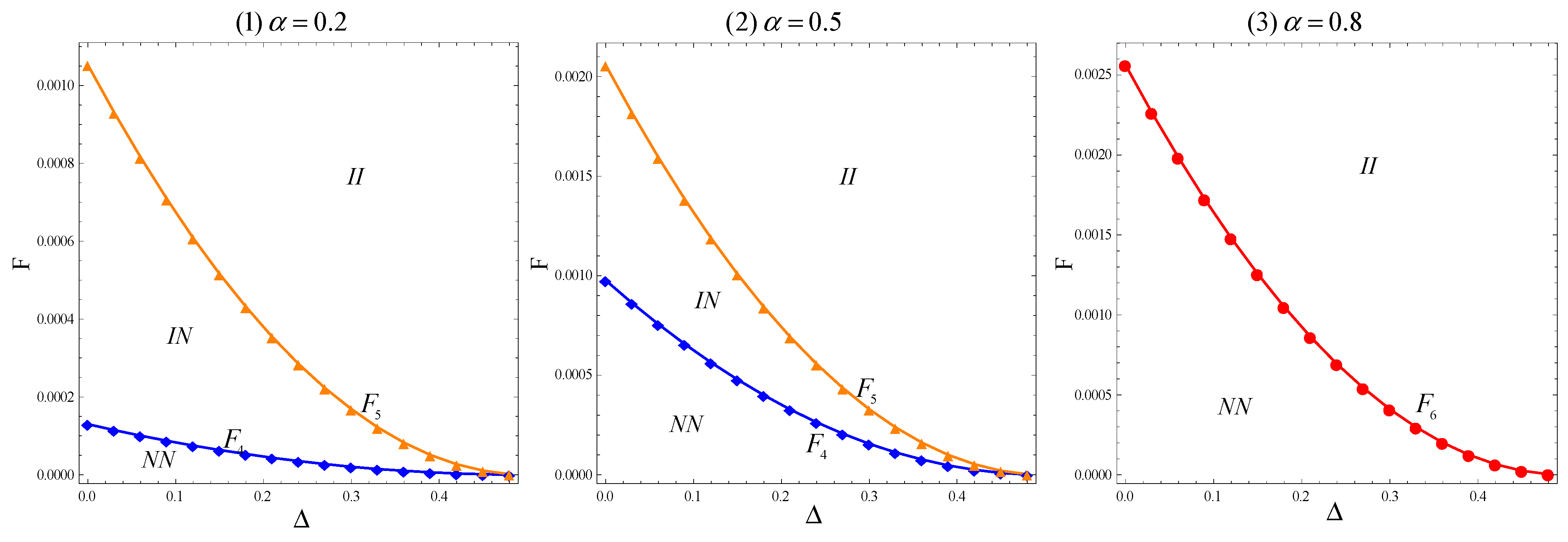

Proposition 8.

When there is an overlap between the two regions:

- (1)

- Without a side payment (), the online retailer will not share any information with either manufacturer;

- (2)

- With a side payment (), there exists thresholds , , , and (in which () are all decreasing in ) such that: (i) when , the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy is NN if , then shifts to IN if , and finally to II if ; (ii) when , the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy is NN if , then shifts to II if . Where , , and .

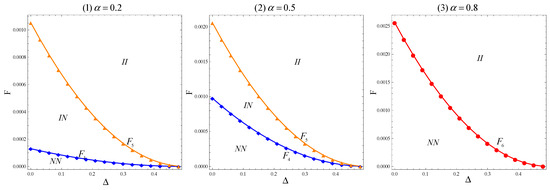

Proposition 8 is illustrated by a numerical example, as presented in Figure 3. Both Proposition 8 and Figure 3 show that when an overlap exists between the two regions, the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy remains qualitatively the same as when there is no overlap between the two regions. Specifically, when the proportion of comparison shoppers is below a threshold (i.e., ), a comparatively low side payment () will still inhibit the online retailer from sharing private consumer information with either manufacturer. In contrast, a sufficiently high side payment (i.e., ) stimulates the online retailer to share information with both manufacturers, due to the dominating effect of the additional large side payment. Otherwise, with a moderate , i.e., , the online retailer prefers to share information solely with manufacturer rather than with manufacturer . When consumers are more likely to be shoppers (i.e., ), the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy shifts from to as increases. The rationale is quite similar to the case when there is no overlap between the two regions.

Figure 3.

The online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy with overlapping consumers, where .

Nevertheless, Proposition 8 shows that the degree to which two regions of consumers overlap (i.e., ) will play a critical role in affecting the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy. Note that the values for () are all decreasing in ; then, as increases, the online retailer becomes more willing to share private consumer information with both manufacturers. The rationale hinges on the negative effect of information uncertainty on pricing strategy. A larger value for equals a higher degree of information uncertainty, which will negatively impact the pricing decisions of two manufacturers; thus, even with a lower side payment gained by sharing information with the manufacturer, the online retailer still has the incentive to share information. By doing so, the online retailer benefits from higher marginal profits and/or larger sales of the two brands.

7. Conclusions

This paper considers a channel structure in which an online retailer sells both the national brand sourced from the national manufacturer and the store brand sourced from the third-party manufacturer to end-consumers. Consumers express different preferences toward the two brands. We investigate, under the assumption that the online retailer can obtain consumer information in confidence, whether the online retailer is motivated to share this information, and if so, to which manufacturer. We specifically consider four possible information-sharing strategies: (a) no information sharing (Scenario ), that is, the online retailer shares the consumer preference information with no manufacturer; (b) full information sharing (Scenario ), that is, the online retailer shares the consumer preference information with both manufacturers; (c) the online retailer shares the consumer preference information with only the national manufacturer (Scenario ); and (d) the online retailer shares the consumer preference information with only the third-party manufacturer (Scenario ).

7.1. Theoretical Implications

Our study makes significant contributions to both the store brand and supply chain information literature by addressing a previously unexplored area: the information strategy matrix in the context of uncertain consumer preferences for store brands. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically analyze how consumer preference information influences the retailer’s decision to share information with manufacturers, offering novel insights into the strategic dynamics of store brand operations.

First, we focus exclusively on consumer preference information regarding store brands, distinguishing our work from prior research that examines cost, demand, supplier, or quality information. By categorizing consumers into low-type and high-type, based on their preference for store brands, we demonstrate how this classification shapes market distributions and strategic decisions. By integrating horizontal differentiation (consumer fitness) and vertical differentiation (the perceived quality of store brands) within the Hotelling model, we establish a unique market demand function that advances our theoretical understanding of store brand competition.

Second, we expand the research on information strategy by examining whether the online retailer should share its private consumer preference information with both the national and third-party manufacturers. Unlike existing studies that focus on traditional supply chain frameworks or specific types of information, our model incorporates key factors such as the probability of low-type consumers, the proportion of comparison shoppers, the side payment, and the degree of information uncertainty. This comprehensive framework allows us to identify scenarios in which sharing information with various stakeholders is advantageous, providing actionable insights for store brand operators.

These contributions not only enrich the theoretical understanding of store brands but also advance the supply chain information literature by highlighting the critical role of consumer preference information in shaping supply chain dynamics and decision-making. Our findings offer a foundation for future research on information-sharing strategies in the context of store brands and beyond.

7.2. Managerial Implications

The findings of this study offer valuable insights and actionable strategies that can directly benefit managers operating within the retail sector, especially those involved with store brands.

Firstly, the decision to share or withhold information is influenced by factors such as side payment thresholds, consumer types, and the proportion of comparison shoppers. Managers should evaluate these factors systematically to determine the most effective strategy. For instance, in markets with a high proportion of comparison shoppers, sharing information with manufacturers can help align pricing strategies and attract price-sensitive consumers. Additionally, managers can use side payment mechanisms to incentivize information sharing when it aligns with their strategic goals. Secondly, managers should leverage advanced data analytics and technology tools to optimize decision-making. For example, machine learning algorithms can predict consumer preferences, while real-time data monitoring systems can track market trends. These tools enable managers to enhance product positioning, pricing strategies, and marketing efforts, ensuring that they can respond swiftly to changing market conditions. By adopting these strategies, managers can improve operational efficiency, enhance collaboration with manufacturers, and drive sustainable growth in the retail sector.

7.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Our study has several limitations that offer opportunities for future research. First, we assume that the information shared by the online retailer is completely accurate. In terms of the difficulty of acquiring consumer information or the occurrence of real-world data errors, one can extend the model to incorporate information accuracy to better reflect real-world scenarios. Second, manufacturers may conduct their own marketing research (e.g., surveys) to obtain consumer preference information at a limited cost, which is not considered in our model. Future research could explore the impact of such activities on information-sharing strategies. Third, our model simplifies consumer loyalty by assuming fixed preferences for the national brand, ignoring potential loyalty to the retailer or other brands. Future research could explore dynamic loyalty models to capture shifting consumer behaviors. Addressing these limitations in future research will further improve our understanding of information-sharing strategies in retail supply chains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.N. and Y.T.; methodology, Y.T. and J.L.; software, Y.T.; validation, Y.N. and J.L.; formal analysis, Y.N.; investigation, Y.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.N.; writing—review and editing, Y.T.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors contributed equally to this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22BGL120).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of Lemma 1.

By backward induction, we first solve the online intermediary’s retail prices of the national brand and the store brand, respectively. Then, assuming high-type consumers, the online intermediary’s profit function is . The Hessian matrix of the profit function is . Therefore, the Hessian matrix is negatively definite because and . Hence, is joint concave in and , and we can obtain and by solving the first-order optimal condition for and . Similarly, we can obtain and , when consumers express low acceptance of the store brand. When we plug and into the profit functions of the national manufacturer and the third-party manufacturer, we have and , respectively. As and , () is concave in (). Therefore, the first-order conditions for and yield and , respectively. Substituting and into the retail prices, we obtain the equilibrium results that are revealed in Lemma 1.

Following the same logic, we can derive the firms’ optimal pricing decisions under Scenarios , , and , respectively. We omit the straightforward algebraic steps here. □

Proof of Proposition 1.

By comparing the wholesale prices and retail prices presented in Lemmas 1–4, we can easily obtain the results that are revealed in Proposition 1. We omit the straightforward algebraic steps here. □

Proof of Proposition 2.

Inserting the optimal retail prices that are presented in Lemmas 1–4 into the demand functions, we achieve the following table.

Then, by comparing the demands presented in Table A1, we can easily obtain the results that are revealed in Proposition 2. We omit the straightforward algebraic steps here. □

Table A1.

The demands with two brands under four scenarios.

Table A1.

The demands with two brands under four scenarios.

Proof of Proposition 3.

The expected profits of the national and third-party manufacturers under four scenarios are:

, , , and ; , , , and .

Then, without a side payment, i.e., , we have , and always holds true, while and do not always hold true.

Following the same logic, with a side payment, we can show that and do not always hold true where . □

Proof of Proposition 4.

The expected profits of the online intermediary under four scenarios are:

Then, without a side payment, i.e., , we have , , and always hold. Therefore, without a side payment, the online retailer’s optimal information sharing format is .

Following the same logic, we can derive the firms’ optimal information-sharing format with a side payment. We omit the straightforward algebraic steps here. □

Proof of Corollary 1.

By taking the first order derivatives of (where ) with respect to and , we can easily derive the results that are presented in Corollary 1. We omit the straightforward algebraic steps here. □

Proof of Proposition 7.

The proof of Proposition 7 comprises two steps. First, we solve the players’ optimal pricing decisions in four information-sharing formats. The process is quite similar to that in the proof of Lemmas 1 and we present the equilibrium pricing decisions in Table A2.

Here, , , , and . By inserting the optimal wholesale and retail prices into the online retailer’s profit function, we can derive the online retailer’s optimal profits under four scenarios.

Second, by comparing the profit differences, we show that the online retailer’s optimal information-sharing strategy is completely the same as that presented in Proposition 6. We omit the straightforward algebraic steps here.□

Table A2.

The equilibrium prices under the four scenarios, with a general point.

Table A2.

The equilibrium prices under the four scenarios, with a general point.

Proof of Proposition 8.

The proof of Proposition 8 comprises two steps. First, we solve the players’ optimal pricing decisions under four information sharing formats. The process is quite similar as that in the proof of Lemmas 1 and we only present the equilibrium pricing decisions in Table A3.

Here, , , , and . By inserting the optimal wholesale and retail prices into the online retailer’s profit function, we can derive the online retailer’s optimal profits under four scenarios.

Second, by comparing the profit differences, we can derive the results that are presented in Proposition 8. We omit the straightforward algebraic steps here. □

Table A3.

The equilibrium prices under the four scenarios when there is an overlap.

Table A3.

The equilibrium prices under the four scenarios when there is an overlap.

References

- Yu, J.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, C. Strategic interactions in omnichannel retailing: Analyzing brand competition and optimal strategy selection. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2557–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xu, Q. Platform first-party product entry and pricing strategy under cost differences and capacity constraints. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2497–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.; Wang, X.; Xu, Y. Platform’s recommendation strategy considering limited consumer awareness and market encroachment. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 2255–2269. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes. Why Private Label Brands Are Having Their Moment. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/errolschweizer/2022/06/30/why-store-brands-are-having-their-moment/?sh=3ccc7a0838bf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Li, Q.; Wang, Q.; Song, P. Third-party sellers’ product entry strategy and its sales impact on a hybrid retail platform. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 47, 101049. [Google Scholar]

- Marketplace Pulse. Amazon Private Label Brands. Available online: https://www.marketplacepulse.com/amazon-private-label-brands (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- JD.com. Available online: https://mall.jd.com/index-1000096602.html?from=pc (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- The Grocer. How Tesco Finest Own Label Offer Is Evolving to Stay Ahead. Available online: https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/own-label/how-tesco-finest-offer-is-evolving-to-stay-ahead-of-the-pack-/572371.article (accessed on 5 October 2018).

- Siqin, T.; Choi, T.; Chung, S.; Wen, X. Platform operations in the industry 4.0 era: Recent advances and the 3As framework. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 1145–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Pora, U.; Gerdsri, N.; Thawesaengskulthai, N.; Triukose, S. Data-driven roadmapping (DDRM): Approach and case demonstration. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2022, 69, 209–227. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, D.J.; Zhang, F. Information sharing on retail platforms. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2021, 23, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Xiao, T. National or third-party manufacturer? Sourcing strategy of a dominant platform: Signaling game’s perspective. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 124, 103016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Agency selling or reselling: E-tailer information sharing with supplier offline entry. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 280, 134–151. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.; Mantrala, M.; Bian, Y. Strategic information management in a distribution channel. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Caldieraro, F. The role of brand image and product characteristics on firms’ entry and OEM decisions. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 3327–3350. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Fang, X.; Xiao, G.; Yang, N. Optimal contract design for a national brand manufacturer under store brand private information. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2023, 25, 1835–1854. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao, L.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, H.; Liu, H. Incentives for disclosing the store brand supplier. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2022, 109, 102590. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Geng, W. To introduce a store brand or not: Roles of market information in supply chains. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 150, 102334. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Hua, Z.; Wang, J.; Lai, F. Equilibrium analysis of markup pricing strategies under power imbalance and supply chain competition. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2017, 64, 464–475. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Cao, K. Optimal brand differentiation and private brand introduction strategies considering carbon emission reduction. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 4608–4620. [Google Scholar]

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Harlam, B. An empirical analysis of the determinants of retail margins: The role of store-brand share. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Erdem, T.; Zhao, Y.; Valenzuela, A. Performance of store brands: A cross-country analysis of consumer store-brand preferences, perceptions, and risk. J. Mark. Res. 2004, 41, 86–100. [Google Scholar]

- Soberman, D.A.; Parker, P.M. The economics of quality-equivalent store brands. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Chen, H.; Chai, J.; Shi, V. Private label sourcing for an e-tailer with agency selling and service provision. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 114–127. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Cai, X.; Chen, J. Quality and private label encroachment strategy. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 374–390. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Yang, W.; Wu, J. Private label management: A literature review. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 368–384. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, T.; Chauhan, S.S.; Huang, X. Quality competition between national and store brands. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 2703–2732. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Niu, W.; Zhang, L.; Xue, W. Store brand introduction in a dual-channel supply chain: The roles of quality differentiation and power structure. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2023, 116, 102802. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Gavirneni, S.; Rao, V.R. Supply chains in the presence of store brands. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 224, 392–403. [Google Scholar]

- Alan, Y.; Kurtuluş, M.; Wang, C. The role of store brand spillover in a retailer’s category management strategy. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2019, 3, 620–635. [Google Scholar]

- Ru, J.; Shi, R.; Zhang, J. Does a store brand always hurt the manufacturer of a competing national brand? Prod. Oper. Manag. 2015, 24, 272–286. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Song, H.; Gu, X.; Shi, V.; Zhu, J. How to compete with a supply chain partner: Retailer’s store brand vs. manufacturer’s encroachment. Omega-Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2021, 103, 102412. [Google Scholar]

- Katewa, S.; Jain, T. Wait or invest early? An analysis of product cocreation in online platforms. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 4862–4875. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Guan, X.; Yi, Z. Quality information disclosure with retailer store brand introduction in a supply chain. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 171, 108475. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.; Choi, T. Supply chain risk analysis with mean-variance models: A technical review. Ann. Oper. Res. 2016, 240, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, A.Y.; Tian, Q.; Tong, S. Information sharing in competing supply chains with production cost reduction. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2017, 19, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsunoda, Y.; Zennyo, Y. Platform information transparency and effects on third-party suppliers and offline retailers. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 4219–4235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Tian, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, F. To share or not to share: Demand forecast sharing in a distribution channel. Mark. Sci. 2016, 35, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, L.; Zhang, J. Demand forecast sharing for a dominant retailer with supplier encroachment and quality decisions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, P. Combating deceptive counterfeits with blockchain technology under asymmetric information. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2024, 71, 3951–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Sun, Q.; Xu, M.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, M. Strategic selling agreement and information management under leakage in an e-commerce supply chain. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2023, 61, 101288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Ha, A.Y.; Tong, S. Information sharing in a supply chain with a common retailer. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tian, L.; Zheng, H. Information sharing in an online marketplace with co-opetitive sellers. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 3713–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotelling, H. Stability in competition. Econ. J. 1929, 39, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ke, H. Impacts of store-brand introduction on a multiple-echelon supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 292, 652–662. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Li, G.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, X. Contingent channel strategies for combating brand spillover in a co-opetitive supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 164, 102830. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Y.; Lu, T.; Li, Y.; Ye, F. Encroachment by a better-informed manufacturer. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 305, 1113–1129. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).