Abstract

This research explores consumer behavior in e-shopping apps, specifically focusing on how the consumers use e-carts and why they abandon them. A model based on the Regulatory Focus Theory was developed to explain the predicted relationships. The study used a self-administered survey to gather 274 qualifying questionnaires from Pakistani online buyers. The partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) technique was used to analyze the data. Empirical findings elaborate that the consumers’ self-suppression motivation to engage in e-shopping encourages e-cart use and decreases e-cart abandonment. Conversely, consumers’ self-expansion motivation increases e-cart abandonment. Also, visiting clearance pages increases cart abandonment. Moreover, when acting as a mediator it increases e-cart abandonment for both the self-suppression and self-expansion motivations. Furthermore, the moderating effects of product involvement were found to influence e-cart use rather than e-cart abandonment. Theoretical contributions and managerial implications for digital marketers are provided.

1. Introduction

As globalization and digitalization advance, the realm of e-commerce is experiencing an unparalleled surge in growth [1]. In the year 2024 alone, it is anticipated that global e-commerce sales will hit USD 6.3 trillion, with forecasts suggesting a continued upward trajectory [2]. Keeping the pace with the dynamic e-commerce landscape is crucial to remain competitive and grasp the newest trends influencing the sector. While the internet and technology provide shoppers with numerous benefits, e-retailers encounter certain inherent challenges, notably e-cart abandonment. E-cart abandonment refers to the act of consumers’ placing items in their e-carts during an e-shopping session but ultimately not making any purchases [3]. It is a recognized managerial challenge for marketers and retailers worldwide, with a staggering abandonment rate of 80% [4], resulting in billions of dollars in unrealized sales. Such elevated abandonment rates prompt marketers to consider two crucial questions. First, what motivates consumers to add items to an e-cart beyond the intention to make a purchase? Second, what factors contribute to e-cart abandonment?

Prior studies have individually explored the incentives behind adding items to e-carts [5] and the perceptual factors influencing e-cart abandonment [3,6,7,8,9,10]. However, there is a research gap in addressing both phases of the online buying process: (1) consumers’ cart usage, defined as the frequency of items added to their cart during a buying session, and (2) cart abandonment, which is the term used when customers end the session without finishing the purchase and leaving the products in their cart.

Every day, millions of users participate in online shopping activities [11]. Nonetheless, user engagement in e-shopping does not always translate into actual purchasing behavior. Numerous users partake in e-shopping for hedonic purposes [5]. Numerous studies (e.g., [12,13,14]) have elucidated that individuals resort to e-shopping as a method of self-escape and emotional regulation. These escapist shoppers view e-shopping engagement as a mechanism for managing their feelings and thoughts rather than solely for purchasing products [15]. Thus, comprehending hedonic motivations, such as self-escapism, is crucial, because they contribute to the individuals’ online non-purchasing behavior, such as e-cart abandonment. Previous research has suggested a link between escapism and e-cart abandonment, but often it has been addressed indirectly rather than directly. For example, Huang et al. [7] incorporated escapism as a component of emotional ambivalence. Additionally, there is a lack of research regarding the specific dimensions of how escapism motivations influence e-cart abandonment [16].

Putting items into an e-cart is a prerequisite for abandonment, because a consumer cannot abandon a cart that is empty. Factors influencing the consumers’ initial usage of e-cart could also affect e-cart abandonment later in the online purchasing journey [17]. In addition to seeking escapism in e-shopping, the consumers’ focus on price savings, such as visiting a website’s clearance page, is also crucial for adding items to their e-carts. While scholars have theorized about the motivations behind cart use (e.g., [6,7] Cho et al., 2006), there has not been a conceptual determination of which online behaviors are specifically linked to the consumers’ e-cart use and abandonment. Hence, this study examines, using a motivational perspective, how the online consumers’ motivations impact both e-cart usage and abandonment behaviors. The purpose of this study is to explore how both dimensions of self-escapism motivation influence e-cart abandonment behavior in online shopping contexts. Understanding this relationship is crucial, as self-escapism often drives impulsive browsing, which may not always translate into purchase intentions, leading to e-cart abandonment. By examining this behavior, the study aims to provide insights into how emotional and psychological factors contribute to incomplete purchases, ultimately helping businesses develop strategies to minimize abandonment rates and enhance customer retention. This has the potential to offer significant contributions to both e-commerce theory and practical applications in digital marketing. Thus, this research evaluates the dimensions of a self-escapism motivation to engage in e-shopping and their impact on the consumers visiting a clearance page of e-shopping app and their e-cart use and abandonment. Moreover, the moderating role of product involvement is examined on the relationship between the consumers visiting a clearance page of e-shopping app, the e-cart use and subsequently e-cart abandonment.

Next, the relevant literature and theoretical background is discussed, and a theoretical model is developed, followed by an overview of methods, results, and discussion. The Section 6 presents managerial recommendations aimed at minimizing cart abandonment and re-engaging consumers to reclaim abandoned e-carts, ultimately enhancing e-commerce sales.

2. Literature Review

An e-cart is a digital space on a retail website where the consumers can browse, select, and temporarily store items before deciding whether to purchase them [17]. Previous studies on e-cart abandonment have predominantly concentrated on identifying its causes, but have not explored the frequency of the consumers’ utilization of the cart or the quantity of items added to a cart during a particular shopping session. Moreover, prior studies, e.g., ref. [3], have identified various significant factors contributing to e-cart abandonment, such as utilizing the cart for research and organization purposes and concerns regarding overall costs. They proposed behavioral and cognitive explanations for abandonment based on the consumers’ motivations for online cart usage. Expanding on this investigation, Xu and Huang [18] delved into the factors affecting e-cart abandonment specifically in China. Their findings revealed that the motivations associated with research and organization lead to higher rates of abandonment, thus affirming the insights put forth by previous research [3], and underscoring the broader relevance of their findings. In addition, Cho et al. [6] categorized hesitancy to buy as a form of cart abandonment. In general, these studies examine cart use and abandonment separately. Moreover, despite the evidence indicating that mobile devices influence e-shopping behaviors (e.g., [19]), this particular line of research has yet to explore how the consumers’ engagement with clearance pages on shopping apps and their level of product involvement impact their cart utilization and abandonment patterns.

Furthermore, it is inherent to human nature to seek escape from negative self-perception. When individuals struggle to meet life demands, the awareness of their shortcomings can be distressing. Engaging in immersive activities serves as a means to escape from this discomforting self-awareness [20,21]. Moreover, Heatherton and Baumeister [22] suggest that the self-escapism motivation arises from an individual’s desire to alleviate the self from the awareness of significant thoughts and unpleasant emotions brought about by unfulfilled life demands. Individuals employ various strategies to escape from negative self-perceptions [23]. These strategies can range from self-destructive behaviors like binge eating, sex addiction, drug abuse, or suicide attempts [21] to more positive activities like sports, playing music, watching films or perusing literary works [24]. The internet has become a dynamic outlet for the individuals seeking an escape from themselves. Thus, people often engage in online activities such as browsing content and e-shopping as means of self-escape [12].

Self-escapism is typically conceptualized as a one-dimensional concept or as a part of an entertainment motivation. However, only a few researchers, such as Stenseng et al. [25], focused on the motive behind self-escapism, and suggested that people participate in an activity not only to develop their sense of self but also to expand it. Based on Higgins’s [26,27] regulatory focus theory (RFT), these studies defined the self-suppression and self-expansion motivations as fundamental dimensions of the motivation behind activity engagement to escape from the self. The self-suppression motivation refers to a personal inclination to evade self-consideration by immersing oneself fully in an activity. Conversely, self-expansion refers to an individual’s inclination to enrich their self-concept through their involvement in an activity. Self-suppression motivation stems from the desire to alleviate negative thoughts and emotions arising from adverse circumstances. Therefore, individuals are more inclined to participate in activities when faced with distressing situations [28] even though this may not necessarily enhance their overall well-being [29]. For instance, van Ingen et al. [30] noted that individuals utilize the internet as a means to manage negative emotional states arising from social issues. In contrast, self-expansion motivation is not linked to adverse social circumstances or emotional discomfort. Instead, it is driven by the desire to enrich one’s self-concept. Individuals guided by the self-expansion motivation engage in activities to achieve ideal outcomes, which can be realized through temporary self-escapism [25]. Despite the existence of the Stenseng et al. [25] study, which is considered a key study on the dimensional effects of the self-escapism motivation on consumer behavior, the literature is scant in the context of its impacts on both e-cart use and the subsequent e-cart abandonment in e-commerce.

3. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

The present study employs Higgins’s [26,27] regulatory focus theory (RFT) to elucidate the proposed association between the self-escapism motivation in e-shopping engagement and the consumers’ actions, including visiting a clearance page of an online shopping app, e-cart utilization, and abandonment. The RFT has demonstrated its efficacy in comprehending various marketing phenomena, e.g., advertising efficiency [31,32], the influence of electronic Word-of-Mouth (e-WOM) [33], managing emotions through shopping [34], and impulsivity [35]. It offers a model for understanding user behavior driven by motivation [36]. It posits that the users’ hedonic desires vary in their essence [37], prompting them to employ distinct approaches to manage them [38]. In particular, the RFT presents two motivational orientations, termed the prevention and promotion foci [36].

Individuals utilize a prevention-focused approach to manage safekeeping and a promotion-focused approach to address productivity exigencies [26,27]. The prevention focus approach is adopted by individuals to mitigate adverse outcomes [38,39] and is associated with one’s obligations [37]. In contrast, the promotion focus approach is linked to individual’s hopes and ambitions [26]. People employ the promotion focus approach to pursue proliferation and progress, thereby encountering positive effects [38]. These self-control approaches profoundly influence personal emotions, reflections, and actions [27]. These are relevant for comprehending various user contexts and behaviors, including social interactions and self-escapism [26].

Furthermore, Stenseng et al. [25] developed two dimensions of the self-escapism motivation to engage in an activity: the self-expansion motivation and the self-suppression motivation. These dimensions were established based on the notions of the prevention and promotion foci. The self-suppression motivation involves seeking momentary relief from the negative aspects of oneself triggered by adverse situations, such as failing to meet responsibilities. The aim of the self-suppression motivation is to reduce discomfort or distress. The self-expansion motivation entails engaging in an activity with the aim of achieving favorable results, e.g., personal growth or progress. The underlying purpose of the self-expansion motivation is to enhance prosperity. Self-escapism motivation dimensions have been explored in various domains, including celebrity fascination and sports [40,41]. So, the present study suggests that both the self-suppression and self-expansion motivations influence the individuals’ engagement in online shopping activities. In particular, it proposes that a self-escapism motivation plays a role in determining the users’ visits to a clearance page of an e-shopping app, as well as their e-cart use and abandonment. Given the distinct objectives underlying the self-suppression and self-expansion motivations, their impact on individuals’ behavior in terms of visiting a clearance page, e-cart use, and abandonment is expected to vary.

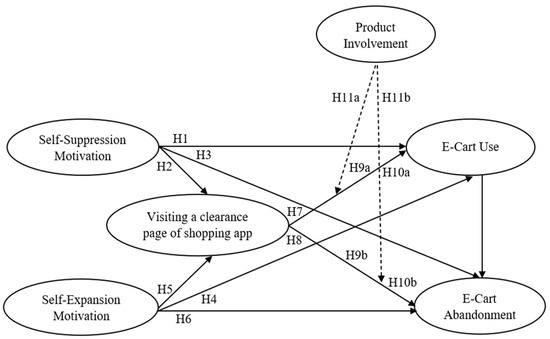

Figure 1 depicts the theoretical model of the study. The model incorporates motivations identified in prior studies [17,42] that are linked to either e-cart usage or abandonment. For instance, Close et al. [43] discovered that the consumers’ inclination to capitalize on price promotions can lead to an increase in the number of items added to a cart. The hypotheses outlined in the model are elaborated upon below.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3.1. Self-Suppression Motivation

Users who are motivated by a self-suppression motivation tend to engage in activities like online shopping in order to evade self-evaluation [25]. Faber [44] noted that people purchase in order to repress negative aspects of their self-awareness. Customers purchase online to get away from issues, concerns, and unfavorable ideas [45]. Previous studies (e.g., [5,46]) have indicated that individuals who participate in online shopping for hedonic purposes tend to populate their carts with items. These shoppers perceive the act of putting goods in e-carts as enjoyable [5]. In line with previous research, the current study proposes that the motivation for self-suppression in online shopping favorably impacts the users’ propensity to utilize the e-cart.

Furthermore, online shoppers can easily compare prices across various websites, and the company that can provide a lower price is seen as more valuable. The internet facilitates price comparison, making it advantageous for consumers to find products at a reduced cost [47,48,49]. The focus on saving money does not just involve monetary savings, it can also encompass avoiding any extra expenses associated with purchasing a product or utilizing a service [50]. When searching for the best bargain, consumers frequently use logic to justify their choices and base them on maximizing their gains from the transaction [51]. Customers will therefore inevitably add products to their virtual carts if they visit a shopping app sale page.

In addition, it is proposed by the current research that the customers’ e-cart abandoning behavior is positively impacted by their self-suppression motivation for e-shopping engagement. Hedonic motivations have been shown to positively influence the users’ e-cart abandoning behavior in other studies [3,10]. Likewise, Wolfinbarger and Gilly [15] noted that escapist shoppers use online shopping activities, such as putting items in their carts, as a way to manage and control their reasoning and emotions, rather than to actually purchase the products. Furthermore, Kukar-Kinney and Close [3] elucidated that as a result, they give up on the e-cart at the conclusion of their online shopping session. The following hypotheses are proposed in light of the aforementioned theorization:

H1.

Self-suppression motivation to engage in e-shopping has a positive influence on the consumers’ e-cart use behavior.

H2.

Self-suppression motivation to engage in e-shopping has a positive influence on the visiting of a clearance page of a shopping app by the customers.

H3.

Self-suppression motivation to engage in e-shopping has a positive influence on the consumers’ e-cart abandonment behavior.

3.2. Self-Expansion Motivation

The self-expansion motivation is not linked to any unfavorable social situations that individuals may encounter. Instead, driven by the self-expansion motivation, users participate in activities to attain favorable outcomes, achievable through temporary self-escape [25]. Growth and advancement are the driving forces behind the self-expansion motivation, in line with the promotion focus strategy [26,27,39]. An individual may take advantage of every chance for growth and advancement, including taking risks and attempting novel experiences [52]. Therefore, people who aspire to grow enjoy investigating and assessing novel concepts, and are not confined to one specific activity, like using an e-cart [34]. Compared to perusing e-store webpages, using an e-cart is a more focused activity [3]. A basic human goal is self-expansion through discovery and learning [53]. Hedonistic online shoppers can choose to peruse product descriptions rather than placing any purchases in e-shopping carts [5].

The present study postulates that consumers who use e-commerce as a means of self-expansion do not restrict their e-cart-loading behavior. Instead, those customers might favor perusing an e-store’s increasing amount of product content. Thus, the current research proposes that consumers’ e-cart use behavior is unaffected by their self-expansion motivation for online shopping engagement. Moreover, the present study suggests that the self-expansionist consumers quit the e-cart at the conclusion of their online buying session, even if they utilize it. Thus, the consumers’ tendency to abandon their online carts is positively impacted by their self-expansion motivation for online shopping. A good user attitude towards e-shopping is encouraged by self-expansion through e-shopping activities [54]. Essentially, this means that users can visit a shopping app’s clearance page, add certain products to their e-carts, and then decide to abandon them. Therefore, the present study postulates that the users’ visits to a shopping app clearance page are positively impacted by their self-expansion motivation to engage in online buying. In particular, the following hypotheses are put forth:

H4.

Self-expansion motivation to engage in e-shopping has no influence on the users’ e-cart use behavior.

H5.

Self-expansion motivation to engage in e-shopping has a positive influence on the consumers’ visiting a clearance page of shopping app.

H6.

Self-expansion motivation to engage in e-shopping has a positive influence on the users’ e-cart abandonment behavior.

3.3. Consumers’ Visiting a Clearance Page of Shopping App

Research demonstrates that the desire to save money affects the use of e-carts [5]. Moreover, the research by Oliver and Shor [9] demonstrates that the customers look for price discounts, and that failing to have a discount code prevents them from completing their online purchases. By lowering the prices, incentives such as discount codes allow clients more financial power. Previous research suggests that a consumer’s desire to save money can be linked to behaviors that stem from an economic control motivation. Hence, a customer’s visit to the clearance section of a shopping app serves as their incentive to save money. Users of the shopping app are proposed to browse the clearance section in order to be encouraged to add more discounted products to their cart. Moreover, in line with the research by Batra and Keller [55], a price reduction incentive is significant early on in the buying process, especially during the observation and attraction phases.

A restricted selection of clearance items is one possible trade-off for the practice of browsing a clearance area on an online shopping website. Overstocked, end-of-season, and less popular products are frequently seen in clearance sections [56]. Hence, things that were first added to a cart due to a sale may no longer look desirable when a customer reaches the stage of making a purchase choice, and other factors may come into greater focus. Particularly, the contradicting cues that combine a low cost with an apparent lack of quality or popularity can cause a bad impression and make the buyer hesitate to complete the transaction [57]. Huang et al. [7] found that hesitation can lead to a higher rate of cart abandonment while making these kinds of buying decisions. Therefore, visiting an e-commerce site’s clearance section is expected to result in a rise in cart abandonment as well as increased cart use.

H7.

Visiting a clearance page of a shopping app increases the online shopping cart use.

H8.

Visiting a clearance page of a shopping app increases the online shopping cart abandonment.

H9a.

Visiting a clearance page of a shopping app by a consumer mediates the relationship between self-suppression motivation and e-cart use.

H9b.

Visiting a clearance page of a shopping app by a consumer mediates the relationship between self-suppression motivation and e-cart abandonment.

H10a.

Visiting a clearance page of a shopping app by a consumer mediates the relationship between self- expansion motivation and e-cart use.

H10b.

Visiting a clearance page of a shopping app by a consumer mediates the relationship between self-expansion motivation and e-cart abandonment.

3.4. Product Involvement

Rubin et al. [8] defined product involvement as an object’s level of personal relevance, which determines an individual’s motivational state towards it. Therefore, items with a higher involvement are more personally relevant than those with lower involvement. Previous e-cart abandonment studies have indicated that consumer involvement with a product has a moderating effect [58]. A brief rise in the perceived value of the product in a particular purchasing scenario is considered involvement, and rises when the product has personal significance and is anticipated to have an immediate effect on the individual [8].

As such, the current research proposes that consumer motivations can influence the importance they ascribe to products, ultimately affecting the likelihood of leaving their e-carts behind via increased involvement. Therefore, as the customers visit a clearance section of a shopping app, their involvement with products will encourage them to add to the e-cart and lead to a higher likelihood that consumers will finalize their purchases. On the other hand, at the end of an e-shopping session, if the product involvement is not very high, customers will simply abandon their e-cart. Thus, it is proposed that:

H11a.

Product involvement strengthens the relationship between the customers’ visit of a clearance section of a shopping app and e-cart use.

H11b.

Product involvement strengthens the relationship between the customers’ visit of a clearance section of a shopping app and e-cart abandonment.

4. Research Methodology

The data were collected via a survey approach through a self-administered questionnaire to gather all the required information. The following are the indicators (questions) of study variables that were obtained from the earlier literature:

Section A of the questionnaire includes the exogenous and endogenous variables. All the questions for each construct adapted from prior studies were evaluated on a 10-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (10). The measurement scale of self-suppression motivation and self-expansion motivation was adapted from Mir [42]. Al-Sabaawi et al. [59] measurement scale was adapted to measure consumers’ visiting a clearance page of shopping app. The product involvement scale was adapted from Hanzaee and Khosrozadeh [60]. E-cart use was measured using the measurement scale of Mir [42]. The e-cart abandonment scale was adapted from Kapoor and Vij [61]. All of the measured items are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Constructs and measured items.

In addition, section B consists of nine items, dealing with demographic variables including age, gender, educational level, job position, marital status, e-shopping experience, frequency, and platform use.

The research team used Google Docs to create an online survey. The easiest way to obtain data is with an online questionnaire [62]. At present, Pakistan has 6.9 million online shoppers [63]. G*Power enables researchers to determine sample sizes based on specified power levels, reducing the likelihood of Type II errors [64]. Therefore, using G*Power (v 3.1), the required sample size was calculated to be 191. The participants in this study comprise users of local B2C e-commerce platforms in Pakistan. Purposive sampling, a non-probability technique, was used to target internet users who shop online in Pakistan. Screening questions ensured that only qualified respondents proceeded with the survey. Prior to initiating the final data collection, a pre-test with 30 online shoppers in Pakistan was conducted to evaluate the questionnaire’s clarity, relevance, and reliability. The feedback led to rewording five items for better comprehension and logical flow. The questionnaire demonstrated strong internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha value of above 0.87 and was deemed suitable for the main data collection phase. Furthermore, the online survey was shared over many platforms, including WhatsApp and Messenger, in an effort to receive as many responses as possible in a brief amount of time. To ensure the data validity in online survey, response bias was minimized through anonymity assurance, clearly defining the purpose of research and pre-testing. Non-response bias was reduced by sending reminders and designing a concise, mobile-friendly questionnaire.

The technique utilized for data analysis was partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). PLS-SEM is a variance-based method ideal for analyzing complex models with latent variables, especially in small sample sizes, like this study, with 191 respondents. It evaluates the measurement model using reliability and validity indices such as outer loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, AVE, and discriminant validity [65]. The structural model is assessed through VIF, path coefficients, R2, f2, and Q2, with model fit determined by SRMR. PLS-SEM also supports mediation and moderation analysis, making it suitable for predictive research without requiring normal data distribution [66]. PLS-SEM is ideal for analyzing questionnaire data when predicting key drivers of a construct, effectively handling complex datasets, multicollinearity, and small sample sizes without assuming data distribution [67,68]. Furthermore, by describing the interactions among different constructs, PLS helps the researcher answer a series of connected research questions in the suggested model [69]. Hence, this study uses PLS-SEM (via Smart PLS 4) to examine direct relationships, with visiting a clearance page of shopping app as a mediator and product involvement as a moderator, following prior research that supports PLS-SEM for mediation and moderation analysis, e.g., [67,70,71].

5. Data Analysis and Results

A descriptive analysis was performed using SPSS version 27. Out of the 289 responses that were received, 274 were deemed sound. Table 2 provides the demographic breakdown of the final responses (274), showing that 60.2% of respondents were men and 39.8% were women. Seventy-three percent of the respondents were in their 20s and 30s. Those with bachelor’s degrees made up the majority of the sample (i.e., 74.1%).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents (N = 274).

A large majority of respondents (87.6%) exhibited high self-suppression motivation (SSM), while only 12.4% had low SSM. Similarly, an overwhelming proportion (94.2%) of participants demonstrated high self-expansion motivation (SEM), whereas only 5.8% had low SEM. In terms of e-cart abandonment behavior (EAB), 86.9% of respondents reported high EAB, while 13.1% had low EAB.

In this study, the impacts of the consumers’ self-suppression motivation, self-expansion motivation, visits to a clearance page of shopping app, and product involvement, on both e-cart use and e-cart abandonment, were analyzed. We aimed to develop an image of the degree to which the six variables are being taken into consideration by using descriptive statistics. However, the issue of the common method bias (CMB) may endanger the consistency of study if all of the data are viewed and gathered simultaneously from a single type of source [70]. Herman’s one factor test was utilized in this study to evaluate the CMB. According to the test, all the components may be divided into six categories, with the first factor explaining only 44.1% of an inconsistency appearing less than 50. The findings indicated that the CMB was not a severe issue for this study; however, while its presence is concerning, this did not mean that the research is worthless [72]. Furthermore, multicollinearity issues should not be present in any study, and the researcher should carefully examine them before moving forward [73]. The variance inflation factor (VIF) is the approach most frequently used to investigate multicollinearity problems in SEM-PLS. The VIF values should generally not be greater than 5 (Hair et al. [73]). The maximum VIF value in the present investigation is 3.671 (<5), indicating that multicollinearity is not an issue.

5.1. Construct Validity

The purpose of construct validity testing is to evaluate how well the outcomes produced using these measures conform to the underlying theory of the test design [74]. To ensure the reliability of the items used to assess a specific construct, each item’s loading with its corresponding latent construct is expected to be 0.7 or higher [66]. It was discovered that certain construct scores in the initial exam, namely PI5 and PI6, did not follow the necessary guidelines. Therefore, they were deleted. After the deletion, all the remaining items affirmed the construct validity [75]. Hence, in our model, this criterion is fully satisfied, as all items exhibit loadings exceeding the specified threshold.

5.2. Convergent Validity

The degree to which several items intended to measure the same concept conform, known as convergent validity, was investigated next. Factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE), as proposed by Hair et al. [75], were used to test it. According to Table 3, every item’s loading exceeds the suggested score of 0.5. Moreover, every item had an AVE score that was higher than 0.5, in accordance with the recommended guideline [76,77]. Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability ratings were then computed to evaluate the inter-item consistency of the measuring items. As demonstrated by Table 3, every alpha score is greater than 0.6, which adheres to the recommended values [78]. In addition, a composite dependability score of 0.70 or above is deemed appropriate [77]. Therefore, it was determined that the measures were trustworthy.

Table 3.

Results of measurement model.

5.3. Discriminant Validity

Examining correlations across possibly overlapping construct sizes allows us to determine the discriminant validity of the measures, or how well the items differentiate between the constructs or measure separate concepts. According to Table 4, this criterion is also fulfilled because the correlation between the construct score and its own is larger than that of the other constructs [79].

Table 4.

Validity analysis.

5.4. Structural Model Analysis

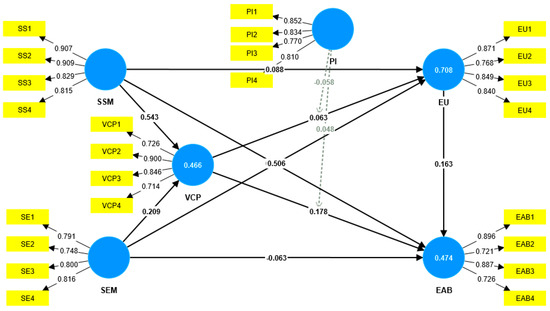

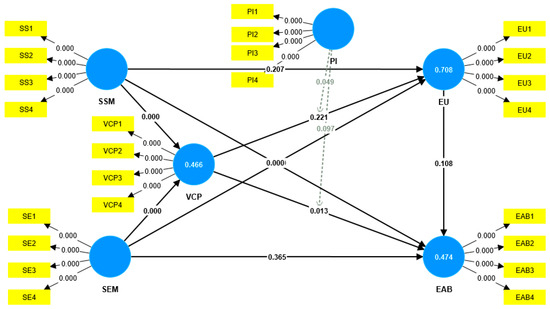

The R2 value, the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR0029, and the Stone–Geisser test (Q2) are the three standard metrics that are usually used to evaluate the model’s fit. Using structural model specifications, the R2 value can be utilized to examine the quality of each variable in a structural model. It is acceptable if the R2 value falls between 0 and 1 [73]. Figure 2 illustrates the significance level of R2 for endogenous latent variables of consumer viewing a shopping app clearance page, e-cart use, and e-cart abandonment (i.e., 46.6%, 70.8%, and 47.4%, respectively).

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM factor loadings, path coefficients, and R2 values.

In addition, the structural equation model demonstrates the relationships between various latent constructs. Figure 3 illustrates the results for the structural model analysis.

Figure 3.

Structural model results.

Moreover, the disparity between the observed correlations and the matrix of indicated correlations in the model is measured by SRMR [80]. The maximum threshold recommended by Hu and Bentler [81] is 0.080, which is the obtained SRMR value. Finally, the PLS prediction process was used to ascertain Q2. The recommended threshold is higher than zero for Q2 [82]. Table 5 shows that the Q2 value is greater than zero (i.e., VCP = 0.451, EU = 0.685, EAB = 0.425), in accordance with [82], and the model demonstrates strong predictive relevance. Thus, based on the three criteria given above, it can be concluded that the model fits well when testing the hypotheses.

Table 5.

Structural model specification.

Table 6 presents the hypothesis testing results. Eight hypotheses were supported including H1, H2, H5, H6, H8, H9b, H10b and H11a.

Table 6.

PLS bootstrapping results.

5.5. Mediation Analysis

The mediation analysis examined the role of visiting the clearance page of a shopping app (VCP) in the relationship between the self-suppression motivation (SSM) and e-cart use (EU). The results indicated that the indirect effect of the SSM on EU through VCP was insignificant (B = 0.034, t = 1.174, p > 0.05), suggesting that the mediator did not significantly transmit the effect. Additionally, the total effect of the SSM on EU was also found to be insignificant (B = 0.122, t = 1.774, p > 0.05). Even after including the mediator, the direct effect of the SSM on EU remained insignificant (B = 0.088, t = 1.263, p > 0.05). These findings (Table 7) demonstrate that visiting the clearance page does not mediate the relationship between self-suppression motivation and e-cart use, leading to the rejection of hypothesis H9a.

Table 7.

Mediation analysis 1.

The mediation analysis examined the role of visiting the clearance page of a shopping app (VCP) in the relationship between self-suppression motivation (SSM) and e-cart abandonment (EAB). The results showed a significant indirect effect of SSM on EAB (B = 0.097, t = 2.293, p < 0.05), indicating that VCP plays a mediating role in this relationship. Additionally, the total effect of SSM on EAB was also significant (B = 0.016, t = 2.611, p < 0.05). Even after including the mediator, the direct effect of SSM on EAB remained significant (B = 0.318, t = 3.806, p < 0.001). These findings (Table 8) suggest that VCP partially mediates the relationship between the self-suppression motivation and e-cart abandonment. Therefore, hypothesis H9b was supported.

Table 8.

Mediation analysis 2.

The mediation analysis evaluated the role of visiting the clearance page of a shopping app (VCP) in the relationship between self-expansion motivation (SEM) and e-cart use (EU). The results showed an insignificant indirect effect of SEM on EU (B = 0.013, t = 1.112, p > 0.05), indicating that VCP does not mediate this relationship. However, the total effect of SEM on EU was significant (B = 0.519, t = 10.124, p < 0.001). After including the mediator, the direct effect of SEM on EU remained significant (B = 0.506, t = 10.355, p < 0.001). These findings (Table 9) demonstrate that VCP does not mediate the relationship between the self-expansion motivation and e-cart use. Therefore, hypothesis H10a was not supported.

Table 9.

Mediation analysis 3.

The mediation analysis explored the role of visiting the clearance page of a shopping app (VCP) in the relationship between the self-expansion motivation (SEM) and e-cart abandonment (EAB). The results revealed a significant indirect effect of SEM on EAB (B = 0.037, t = 2.009, p < 0.05), indicating that VCP mediates this relationship. However, the total effect of SEM on EAB was insignificant (B = 0.059, t = 1.002, p > 0.05), and the direct effect remained insignificant after including the mediator (B = −0.063, t = 0.905, p > 0.05). These findings (Table 10) suggest that VCP fully mediates the relationship between self-expansion motivation and e-cart abandonment. Therefore, hypothesis H10b was supported.

Table 10.

Mediation analysis 4.

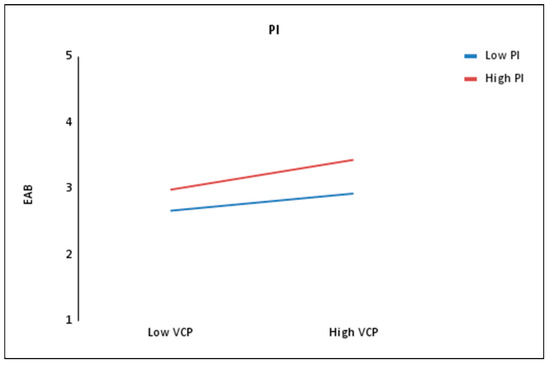

5.6. Moderation Analysis

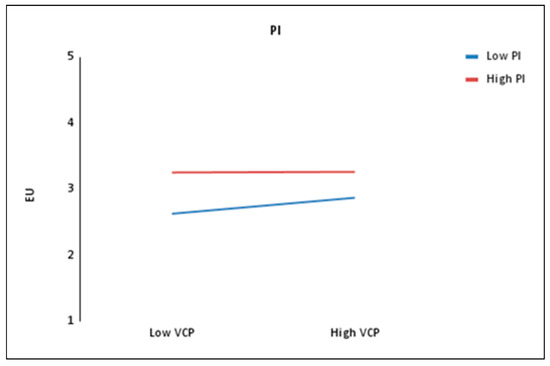

The study examined the moderating role of product involvement (PI) in the relationship between visiting the clearance page (VCP) of a shopping app and e-cart use (EU). The initial analysis, without considering the moderating effect, revealed an R2 value of 0.684, indicating that 68.4% of the variance in EU could be explained by VCP. When the interaction term (VCP × PI) was included, the R2 value increased to 0.708, reflecting a 2.4% rise in the explained variance of EU, suggesting that PI has an additional, though modest, contribution to explaining e-cart use.

Further analysis of the moderating effect (Table 11) showed a negative and significant impact of PI on the relationship between VCP and EU (B = −0.058, t = 1.973, p < 0.05), thus supporting hypothesis H11a. This negative coefficient indicates that as PI increases, the strength of the relationship between VCP and EU weakens. In other words, users with higher product involvement are less influenced by clearance page visits when it comes to adding items to their e-cart.

Table 11.

Moderation analysis of PI on VCP and EU.

To further explore the nature of this moderating effect, a slope analysis was conducted. The slope graph (Figure 4) illustrated that the relationship between VCP and EU is considerably stronger at lower levels of PI, as indicated by a steeper slope. Conversely, at higher levels of PI, the slope flattens, suggesting that an increase in visits to the clearance page does not lead to a comparable increase in e-cart use. This indicates that product involvement dampens the influence of clearance page visits on e-cart behavior, with the relationship becoming less pronounced as the PI rises.

Figure 4.

Moderation effect of PI on VCP -> EU.

Lastly, the effect size (f2) for the moderation effect was calculated at 0.021. According to Cohen’s [83] guidelines, where 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively, this result corresponds to a small effect. This finding suggests that, while the moderation effect of PI on the relationship between VCP and EU is statistically significant, it does not contribute substantially to explaining variations in e-cart use.

Furthermore, the study examined the moderating role of product involvement (PI) on the relationship between visiting the clearance page (VCP) of a shopping app and e-cart abandonment (EAB). The initial analysis, without considering the moderating effect, revealed an R2 value of 0.459, indicating that 45.9% of the variance in EAB could be explained by VCP. When the interaction term (VCP × PI) was included, the R2 value increased slightly to 0.474, reflecting a 1.5% rise in the explained variance of EAB. This suggests that PI contributes minimally to explaining e-cart abandonment when considered as a moderating factor.

A further analysis of the moderating effect (Table 12) revealed a positive but insignificant impact of PI on the relationship between VCP and EAB (B = 0.048, t = 1.660, p > 0.05), leading to the rejection of hypothesis H11b. This result indicates that changes in PI do not significantly influence the relationship between VCP and EAB. In other words, regardless of the level of product involvement, the effect of visiting the clearance page on e-cart abandonment remains largely unchanged.

Table 12.

Moderation analysis of PI on VCP and EAB.

A slope analysis was conducted to better understand the nature of the moderating effects. The slope graph (Figure 5) demonstrated that the relationship between VCP and EAB is stronger at high levels of PI, as indicated by a steeper slope. Conversely, the slope flattens at low levels of PI, suggesting that increases in visits to the clearance page have a diminished effect on e-cart abandonment among the users with low product involvement. This indicates that while a higher PI may reinforce the relationship between VCP and EAB, the effect is not statistically significant.

Figure 5.

Moderation effect of PI on VCP -> EAB.

The effect size (f2) for the moderation effect was calculated at 0.008. According to Cohen’s [83] benchmarks, where 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively, this result indicates a negligible effect. Therefore, while there is some indication that product involvement may influence the relationship between clearance page visits and e-cart abandonment, its moderating effect does not contribute meaningfully to explaining variations in e-cart abandonment.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This study confirms that consumers’ e-cart use and abandonment behaviors are highly influenced by the self-escapism motivation for e-shopping. The study proposed a research model with fourteen hypotheses in order to achieve this. There were three categories for the hypotheses. The first group examined the direct impacts on the customers’ use of e-carts, abandonment of e-carts, and visits to a shopping app’s clearance page. The results showed that consumers’ e-cart use behavior is positively impacted by the self-suppression motivation. This aligns with the earlier studies [42]. Thus, H1 was supported. Moreover, the self-suppression motivation has a positive and significant influence on the consumers’ visits to a clearance page of a shopping app, supporting H2. However, the self-suppression motivation did not significantly influence e-cart abandonment behavior. This is in line with the earlier studies [42]. Due to the fact that for escapist consumers, adding items to their e-cart is a highly focused activity, they may consequently proceed with purchasing the product [42]. Thus, H3 was rejected.

Furthermore, the self-expansion motivation did not significantly influence the e-cart use, as theorized in this study (Hypothesis 4). It means that escapist customers will be inclined to browse more and more content, obtain product information, and exit. They will not necessarily add items to their e-cart. This result is consistent with the previous studies [42]. Therefore, H4 was supported. In addition, a self-expansion motivation has a significant impact on the customers’ visit to a clearance page of a shopping app. The customers visit the clearance page to obtain more information about the products and prices, thus, supporting H5. Moreover, a self-expansion motivation significantly impacts the consumers’ e-cart abandonment behavior. This result supports the previous research [42]. Escapist customers engage in e-shopping to expand their knowledge. So, when their shopping session ends, the items they added to their e-cart are abandoned. Hence, H6 is supported.

In addition, the consumers’ visits to the clearance page of a shopping app did not significantly influence their e-cart use behavior in the current study. This result is inconsistent with previous research [17]. This could be because the customers are motivated by price reductions, which can impact cart usage. For example, they might check a shopping app clearance page as a means of exercising financial control [5]. Thus, H7 was rejected. Moreover, consumers visiting the clearance page of shopping app significantly influenced their e-cart abandonment behavior, so, H8 was supported. Previous research has supported this result [17].

The second group was focused on the mediation impacts of the consumers’ visits to the clearance page of a shopping app on the relationship between the self-escapism motivation, e-cart use, and e-cart abandonment behaviors. The outcomes indicated that consumers’ visiting a clearance page of shopping app did not mediate the relationship between their self-suppression motivation and e-cart use behavior. Thus, H9a was rejected. Furthermore, the consumers visits to a clearance page of a shopping app mediated the association amid self-suppression motivation and e-cart abandonment. Therefore, H9b was supported. Next, the relationship between a self-expansion motivation and e-cart use was not mediated by the consumers visits to a clearance page of a shopping app. Hence, H10a was not supported in this study. Additionally, the consumers visits to a clearance page of a shopping app mediated the connection between a self-expansion motivation and e-cart abandonment. Thus, H10b was supported.

The third group examined the moderating impact of product involvement on the relationship between the consumers visits to a clearance page of a shopping app and their e-cart use and the subsequent e-cart abandonment behavior. The outcomes indicated that product involvement significantly moderates the relationship between consumers’ visiting a clearance page of shopping app and e-cart use behavior. So, it means that once escapist consumers visit a clearance page of a shopping app, as a price-saving tactic or to compare the prices of products which are highly relevant to them, they can add them to the e-cart. Thus, H11a was supported. Therefore, the stronger the impact of product involvement, consumers will add items to the e-cart. Furthermore, product involvement did not moderate the relationship between consumers’ visiting a clearance page of shopping app and e-cart abandonment. It exhibits that once consumers visit the clearance page of shopping app, if the products are not highly relevant to them, they will not add them to the e-cart and may purchase the items. Thus, H11b was not supported.

7. Contributions and Implications

This study makes several key contributions to the existing literature on marketing. The first contribution is the development of a theoretical model that specifically takes the use of e-carts and their subsequent abandonment into account, extending the regulatory focus theory and testing it empirically. This theory helps explain the rationale behind a customer’s decision to add products to their e-cart, and then abandon it. Moreover, this study adds to the existing literature on the relationship between e-cart use and abandonment as part of the consumer’s overall e-shopping journey, which has not been fully explored in the previous studies. Furthermore, an envisioned contribution is to assess the moderating role of product involvement, as its role may have an impact on the consumers’ cart use. Therefore, depending on product involvement, consumer e-cart behaviors may differ [8]. Moreover, the identification of the mediating role of the consumers’ visits to a clearance page of a shopping app as a price-saving tactic is another contribution of this study. Both the self-suppressor and self-expander shoppers have a favorable influence on whether or not they visit the shopping app’s clearance page. As a result, its function may affect how the customers utilize e-carts for purchases and why they abandon them later (e.g., [17]). These insights provide a nuanced understanding of how the different motivations shape online shopping behavior, challenging some existing findings on price-driven purchasing decisions.

Furthermore, this study revealed the key motivations engaging the consumers in e-shopping and then either purchasing the items or abandoning the e-cart. Identifying pertinent online behaviors not only contributes theoretically to the e-cart literature but also enables more substantial managerial contributions, as e-retailers can monitor customer browsing behavior, but they may not discern their buying motivations. This contribution expands on previous research which has independently examined the motivations behind e-cart usage [43], and the factors influencing cart abandonment [7]. This allowed us to uncover the intricacies related to behaviors that differ in their association with e-cart abandonment and utilization.

The demographic insights highlight the need for e-commerce businesses to tailor their marketing and engagement strategies to a young, educated audience, that exhibits high self-escapism motivation and frequent e-cart abandonment behavior. Since a significant portion of the respondents are in their 20s and 30s, with a Bachelor’s degree, digital engagement strategies should align with their browsing habits and purchasing behaviors. Consumers with a high self-suppression motivation are more likely to engage deeply in the shopping process, making it essential for businesses to offer personalized recommendations and AI-driven shopping assistants that guide them toward purchase completion. On the other hand, self-expansion motivated consumers prefer extensive browsing and information gathering before making decisions, making interactive content such as product comparisons, expert reviews, and video demonstrations effective in converting their interest into sales.

Given that a large majority of the respondents reported high e-cart abandonment behavior, businesses need to implement strategies that counteract this trend. Automated cart recovery tactics, including reminder emails, push notifications, and personalized discounts, can help re-engage consumers who leave items in their carts. The influence of clearance page visits on e-cart abandonment suggests that integrating urgency-driven promotions, such as “low stock” alerts and time-limited deals, can encourage faster purchasing decisions. Since men make up a larger proportion of the respondents, while women are also a significant segment, gender-specific marketing approaches should be considered. Men, often more goal-oriented in their shopping behavior, may respond well to simplified checkout processes, express shipping, and product bundles. In contrast, women, who are likely to engage in more detailed browsing and comparison, may be more influenced by comprehensive product descriptions, influencer endorsements, and loyalty rewards programs.

Optimizing clearance pages is another crucial strategy, as many consumers visit these pages before making final purchasing decisions. Personalizing these pages with tailored product recommendations and dynamic pricing adjustments can increase conversions. Flash deal countdowns and limited-time clearance offers can also create a sense of urgency, motivating consumers to complete their purchases. Additionally, given the younger demographic of the respondents, businesses should focus on mobile-first strategies, ensuring a seamless app interface, AI-powered chatbot support, and exclusive in-app discounts. Social commerce integration, such as enabling purchases directly through platforms like Instagram or TikTok, can further appeal to young consumers who are heavily influenced by digital content and social proof. By implementing these tailored strategies, e-commerce businesses can better engage their target audience, reduce e-cart abandonment, and enhance overall conversion rates.

8. Limitations and Future Research

The contributions of this study should be considered within the context of its limitations. First, only consumers in Pakistan were used to obtain data. Comparatively, Pakistani culture is collectivist. Therefore, to achieve the purpose of determining the study generalizability, future investigations should duplicate the existing model in individualistic cultural contexts. Prior studies (e.g., Sakarya and Soyer [84]) have indicated that cultural factors influence the e-shopping behaviors of both utilitarian and hedonistic consumers. Second, other factors, such as product presentation, might have a direct impact on how the customers use and abandon their e-carts in addition to those covered in this study. Additionally, this research took into account the moderating role of product involvement. Other moderators such as age, gender, social impact, VR, and AI technology should be investigated by researchers in future research. In addition, subsequent studies must take into account the influence of other mediators, such as consumer habits. The research model employed in this study may be extended further using such constructs in future studies. Third, the current study studied consumer e-cart use and abandonment behavior in e-shopping; “consumer e-cart use and abandonment behavior” in other sectors should be considered in future research, for example in specific industry sectors, such as the fashion sector. Fourth, the present investigation employed a quantitative approach to gather data; subsequent studies should incorporate qualitative techniques such as interviews or mixed methods to provide comprehensive insights. Lastly, longitudinal studies can provide more accurate consumer behavior data, as the researchers can observe the changes over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.S.M. and A.F.; methodology, A.F. and N.A.H.N.A.; software, H.A.S.M., A.F. and T.T.I.; validation, H.A.S.M., A.F., N.A.H.N.A., S.H., T.T.I. and T.S.H.; formal analysis, H.A.S.M., S.H., T.T.I. and T.S.H.; investigation, H.A.S.M.; resources, A.F., N.A.H.N.A., S.H., T.T.I. and T.S.H.; data curation, H.A.S.M., S.H., T.T.I. and T.S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.A.S.M. and T.T.I.; writing—review and editing, A.F., S.H. and T.T.I.; visualization, H.A.S.M., T.T.I. and T.S.H.; supervision, A.F. and N.A.H.N.A.; project administration, A.F. and H.A.S.M.; funding acquisition, H.A.S.M., A.F., S.H., T.T.I. and T.S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Musonda, I.; Onososen, A.; Moyo, T. Digital Transitioning in the Built Environment of Developing Countries; Taylor & Francis: Oxford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Statista. E-Commerce Worldwide—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/871/online-shopping/#topicOverview (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Kukar-Kinney, M.; Close, A.G. The Determinants of Consumers’ Online Shopping Cart Abandonment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2010, 38, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Percentage of Baskets Created That Did Not Result in a Completed Order for Cosmetics Worldwide in 2nd Quarter 2023, by Device. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1416608/cart-abandonment-rate-worldwide-makeup/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Close, A.G.; Kukar-Kinney, M. Beyond Buying: Motivations behind Consumers’ Online Shopping Cart Use. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.-H.; Kang, J.; Cheon, H.J. Online Shopping Hesitation. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.-H.; Korfiatis, N.; Chang, C.-T. Mobile Shopping Cart Abandonment: The Roles of Conflicts, Ambivalence, and Hesitation. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.; Martins, C.; Ilyuk, V.; Hildebrand, D. Online Shopping Cart Abandonment: A Consumer Mindset Perspective. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Shor, M. Digital Redemption of Coupons: Satisfying and Dissatisfying Effects of Promotion Codes. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2003, 12, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-D. A Study on Online Shopping Cart Abandonment: A Product Category Perspective. J. Internet Commer. 2019, 18, 337–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enberg, J. Prime Is Key to Amazon’s International Expansion. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/prime-is-key-to-amazon-s-international-expansion (accessed on 7 May 2024).

- Bui, M.; Kemp, E. E-tail Emotion Regulation: Examining Online Hedonic Product Purchases. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-Y. Escapism, Consumer Lock-in, Attitude, and Purchase: An Illustration from an Online Shopping Context. J. Shopp. Cent. Res. 2005, 12, 109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, F.M.; Kirazli, Ö. Analyzing Motivational Determinants of Shopping Addiction Tendency. Ege Akad. Bakis (Ege Acad. Rev.) 2019, 19, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfinbarger, M.; Gilly, M.C. Shopping Online for Freedom, Control, and Fun. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazhar, R.; Qayyum, A.; Jamil, R.A. The Dimensional Impact of Escapism on Users’ ECart Abandonment: Mediating Role of Attitude towards Online Shopping. Manag. Res. Rev. 2024, 47, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukar-Kinney, M.; Scheinbaum, A.C.; Orimoloye, L.O.; Carlson, J.R.; He, H. A Model of Online Shopping Cart Abandonment: Evidence from e-Tail Clickstream Data. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 961–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, J.-S. Factors Influencing Cart Abandonment in the Online Shopping Process. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1617–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.W.; Guijun, Z.; Ikram, A.; Anwar, B. Consumers’ Device Choice in E-Retail: Do Regulatory Focus and Chronotype Matter? KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2020, 14, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatard, A.; Selimbegović, L. When Self-Destructive Thoughts Flash through the Mind: Failure to Meet Standards Affects the Accessibility of Suicide-Related Thoughts. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 100, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Suicide as Escape from Self. Psychol. Rev. 1990, 97, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Baumeister, R.F. Binge Eating as Escape from Self-Awareness. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F. Neglected Aspects of Self-Theory: Motivation, Interpersonal Aspects, Culture, Escape, and Existential Value. Psychol. Inq. 1992, 3, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenseng, F.; Rise, J.; Kraft, P. Activity Engagement as Escape from Self: The Role of Self-Suppression and Self-Expansion. Leis. Sci. 2012, 34, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Beyond Pleasure and Pain. Am. Psychol. 1997, 52, 1280–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, E.T. Promotion and Prevention: Regulatory Focus as a Motivational Principle. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Levenson, R.W. Emotional Suppression: Physiology, Self-Report, and Expressive Behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 64, 970–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenseng, F. A Dualistic Approach to Leisure Activity Engagement: On the Dynamics of Passion, Escapism, and Life Satisfaction. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van Ingen, E.; Utz, S.; Toepoel, V. Online Coping After Negative Life Events. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.P.; Agrawal, N.; Maheswaran, D. When More May Be Less: The Effects of Regulatory Focus on Responses to Different Comparative Frames. J. Consum. Res. 2006, 33, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Grace, D.; Ross, M. Self-Regulatory Focus and Advertising Effectiveness. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 612–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Q.; Craciun, G.; Shin, D. When Does Electronic Word-of-Mouth Matter? A Study of Consumer Product Reviews. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 1336–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.J.; Reynolds, K.E. Affect and Retail Shopping Behavior: Understanding the Role of Mood Regulation and Regulatory Focus. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G. Retail Shopping Behaviour: Understanding the Role of Regulatory Focus Theory. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2015, 25, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Nakkawita, E.; Cornwell, J.F.M. Beyond Outcomes: How Regulatory Focus Motivates Consumer Goal Pursuit Processes. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 3, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Higgins, E.T. Regulatory Focus Theory: Implications for the Study of Emotions at Work. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Roney, C.J.R.; Crowe, E.; Hymes, C. Ideal versus Ought Predilections for Approach and Avoidance Distinct Self-Regulatory Systems. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 66, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Sato, A. The Psychology of Impulse Buying: An Integrative Self-Regulation Approach. J. Consum. Policy 2011, 34, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, J.; Day, L. Regulatory Motivations in Celebrity Interest: Self-Suppression and Self-Expansion. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2017, 6, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ganideh, S.F.; Good, L.K. Cheering for Spanish Clubs: Team Identification and Fandom of Foreign Soccer Clubs (the Case of Arab Fans). Int. J. Sport. Psychol. 2015, 46, 348–368. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, I.A. Self-Escapism Motivated Online Shopping Engagement: A Determinant of Users’ Online Shopping Cart Use and Buying Behavior. J. Internet Commer. 2021, 22, 40–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, A.G.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Benusa, T.K. Toward a Theory of Consumer Electronic Shopping Cart Behavior: Motivations of e-Cart Use and Abandonment. In Online Consumer Behavior; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, R.J. Self-Control and Compulsive Buying. In Psychology and Consumer Culture: The Struggle for a Good Life in a Materialistic World; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathwick, C.; Malhotra, N.; Rigdon, E. Experiential Value: Conceptualization, Measurement and Application in the Catalog and Internet Shopping Environment☆11☆This Article Is Based upon the First Author’s Doctoral Dissertation Completed While at Georgia Institute of Technology. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, T.P.; Hoffman, D.L.; Duhachek, A. The Influence of Goal-directed and Experiential Activities on Online Flow Experiences. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 3, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.; Wang, E.T.G.; Fang, Y.; Huang, H. Understanding Customers’ Repeat Purchase Intentions in B2C E-commerce: The Roles of Utilitarian Value, Hedonic Value and Perceived Risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K.; Nilsson, D. Determinants of the Continued Use of Self-Service Technology: The Case of Internet Banking. Technovation 2007, 27, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, L.; Calantone, R. A Comparison of Three Models to Explain Shop-bot Use on the Web. Psychol. Mark. 2002, 19, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Online Purchasing Tickets for Low Cost Carriers: An Application of the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) Model. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollila, S. Consumers’ Attitudes towards Food Prices. Food Econ. 2011, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Sassenberg, K.; Scholl, A. Linking Regulatory Focus and Threat–Challenge: Transitions between and Outcomes of Four Motivational States. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 30, 174–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Lewandowski Jr, G.W.; Mashek, D.; Aron, E.N. The Self-Expansion Model of Motivation and Cognition in Close Relationships. In The Oxford Handbook of Close Relationships; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 90–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kou, Y.; Powpaka, S. Why Friends Pay More: An Alternative Explanation Based on Self-Expansion Motives. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2017, 45, 1537–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Keller, K.L. Integrating Marketing Communications: New Findings, New Lessons, and New Ideas. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 122–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.A.; Achabal, D.D. Clearance Pricing and Inventory Policies for Retail Chains. Manag. Sci. 1998, 44, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, A.D.; Grewal, D.; Goodstein, R.C. The Effect of Multiple Extrinsic Cues on Quality Perceptions: A Matter of Consistency. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheah, J.; Lim, X. Online Shopping Cart Abandonment: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabaawi, M.Y.M.; Alshaher, A.A.; Alsalem, M.A. User Trends of Electronic Payment Systems Adoption in Developing Countries: An Empirical Analysis. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2023, 14, 246–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanzaee, K.H.; Khosrozadeh, S. The Effect of the Country-of-Origin Image, Product Knowledge and Product Involvement on Information Search and Purchase Intention. Middle-East. J. Sci. Res. 2011, 8, 625–636. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, A.P.; Vij, M. Following You Wherever You Go: Mobile Shopping ‘Cart-Checkout’ Abandonment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 61, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.-N.; Algahtani, F.D.; Atteya, M.R.; Almishaal, A.A.; Ahmed, A.A.; Obeidat, S.T.; Kamel, R.M.; Mohamed, R.F. The Impact of Extended E-Learning on Emotional Well-Being of Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Children 2021, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Economic Net. Pakistan’s E-Commerce Market Is Expected to Reach $6.7 Billion by 2029. Available online: http://en.ce.cn/Insight/202412/17/t20241217_39237963.shtml?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 21 February 2025).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Talukder, M.S.; Islam, Q.T.; Islam, A.K.M.N. The Impact of Business Analytics Capabilities on Innovation, Information Quality, Agility and Firm Performance: The Moderating Role of Industry Dynamism. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2022, 54, 1124–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D.L.; Thompson, R.; Lewis, W. Why You Shouldn’t Use PLS: Four Reasons to Be Uneasy about Using PLS in Analyzing Path Models. In Proceedings of the 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013; pp. 4739–4748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawan, A.; MZ, M.D.; Elmi, F.; Riyanto, S. The Role of Lecturer Commitment in Determining Organisational Behaviour. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2023, 16, 219–254. [Google Scholar]

- Tehseen, S.; Ramayah, T.; Sajilan, S. Testing and Controlling for Common Method Variance: A Review of Available Methods. J. Manag. Sci. 2017, 4, 142–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications, Incorporated: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sekaran, U.; Bougie, R. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, D.; Higgins, C.; Thompson, R. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Casual Modeling: Personal Computer Adoption Ans Use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 284–324. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A Partial Least Squares Latent Variable Modeling Approach for Measuring Interaction Effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and an Electronic-Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. A Practical Guide to Factorial Validity Using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and Annotated Example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing Measurement Model Quality in PLS-SEM Using Confirmatory Composite Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM): An Emerging Tool in Business Research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sakarya, S.; Soyer, N. Cultural Differences in Online Shopping Behavior: Turkey and the United Kingdom. Int. J. Electron. Commer. Stud. 2013, 4, 239–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).