2.2. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) is a thorough framework for grasping how people embrace and keep utilizing technological systems [

23]. UTAUT provides useful insights regarding the technical elements affecting Generation Z’s ongoing involvement and repurchase patterns in the framework of social commerce platforms [

24]. The model consists of four main constructs—performance expectation, effort expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions—each of which contributes uniquely to users’ behavioral intents and actual use patterns [

25].

Performance expectation is the extent to which people think using a certain technology would improve their performance in certain tasks [

26]. In social commerce, this shows up as customers’ views on how well platforms support their shopping goals, including product discovery, comparison, and purchase completion [

27].

Studies show that customers’ intentions to participate in recurrent buying behaviors rise dramatically when they see social commerce platforms as offering large utilitarian advantages—including time efficiency, product diversity, and competitive pricing—especially when they view social commerce platforms [

28]. Performance expectancy is especially important for Generation Z customers, who value efficiency and effectiveness in their technology interactions, since it affects their repurchase choices [

8]. Performance-related elements are emphasized by Jebarajakirthy, Yadav and Shankar [

5] when they say that, for a successful acquisition to occur, technology-related firms should invest in market orientation during the early stages of the firm’s life cycle, stressing the need for these elements to keep technologically native consumers.

In competitive market settings, where many platforms compete for customer attention and loyalty, the link between performance anticipation and repurchase intention becomes more pronounced [

29]. In such situations, Generation Z customers’ assessments of platform performance in comparison with substitutes greatly influence their ongoing involvement choices [

30]. Social commerce platforms that regularly outperform in supporting shopping goals are thus better positioned to foster repurchase habits among Generation Z consumers [

31]. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

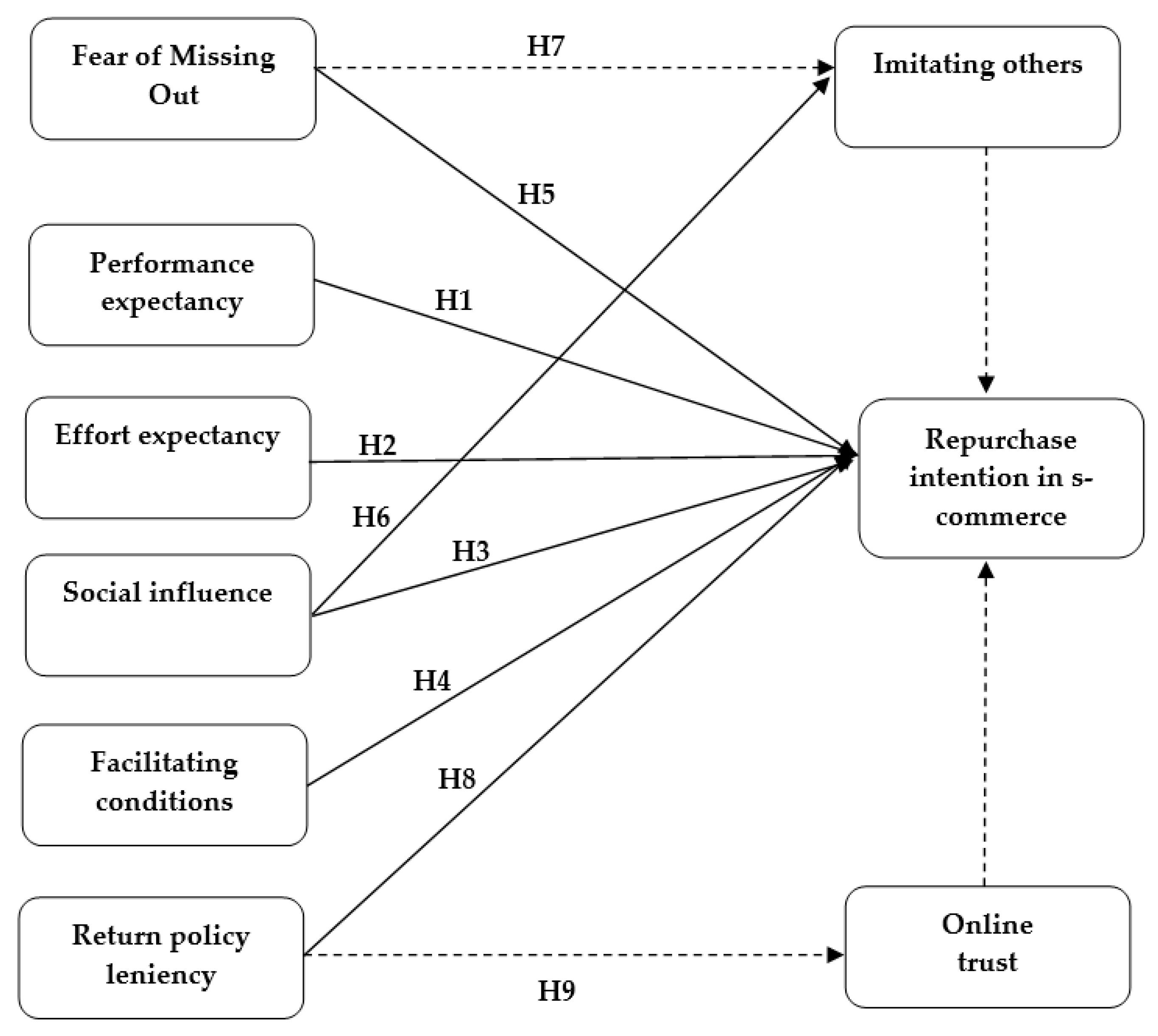

H1: Performance expectancy positively impacts Generation Z’s repurchase intention in social commerce.

Effort expectation relates to the perceived simplicity linked to utilizing a technological system [

23]. For Generation Z consumers of social commerce platforms, effort expectation includes the intuitiveness of interfaces, streamlined checkout procedures, and smooth movement between social and commercial functionalities [

26]. Though they are technically savvy, Generation Z customers still place great importance on cognitive economy when choosing and using platforms [

9,

32].

Studies show that consumers of social commerce sites defined by low learning needs, simple design features, and easy checkout procedures have more repurchase intentions [

33]. Khoa and Thanh [

34] point out that perceived control is lower on personalized websites than on non-personalized websites, which leads to privacy concerns during online transactions. Transparent information and simplified processes, meanwhile, may help to reduce these worries and improve consumers’ readiness to participate in recurrent buying activities [

35].

Specifically for Generation Z customers, the cognitive resources saved by simple platform interactions may be transferred towards more interesting elements of the buying process, like product assessment and social involvement [

10]. This change improves general shopping process satisfaction, hence increasing repurchase intentions [

36]. Furthermore, the favorable link between effort expectation and repurchase intention should intensify as users become more acquainted with platform features over time because ease of use changes from being just appreciated to being anticipated [

37]. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H2: Effort expectancy positively impacts Generation Z’s repurchase intention in social commerce.

Social influence is the degree to which people feel that important others think they should adopt a certain technology [

23]. Particularly in social commerce settings, where peer recommendations and social validation greatly affect Generation Z’s buying choices, this aspect is very important [

38]. This demographic group shows more sensitivity to peer views and social validation, which makes them more vulnerable to influence from reference groups in their buying choices [

39].

Social influence in Generation Z’s consumption contexts operates through multiple distinct mechanisms requiring deeper theoretical exploration. Beyond the general definition provided by UTAUT, social influence manifests through (1) normative processes, where conformity is driven by desire for social approval [

40]; (2) informational processes, where peers’ actions serve as information shortcuts under uncertainty [

41]; and (3) identification processes, where consumption aligns with reference group identity [

42]. For Generation Z specifically, social influence operates through unique digital mechanisms including algorithmic recommendations, visibility metrics (likes, shares), and peer-generated content that serves as consumption cues [

43]. These influence pathways are particularly potent in social commerce environments where identity signaling through consumption is embedded within social networking structures [

44]. The platforms’ architecture amplifies social influence by making peer preferences highly visible and reducing barriers between observing others’ consumption and one’s own purchase actions [

45].

In social commerce settings, when commercial operations are integrated into social networking environments, the impact of peers, opinion leaders, and larger social networks becomes amplified [

46]. Studies show that herding is a behavior in which investors follow the actions of other investors, leading to herd effects and potentially irrational investment decisions [

18]. Social commerce environments also follow this concept; Generation Z customers often adjust their buying behavior based on seen trends among peers [

47].

Social influence manifests itself via many routes within social commerce platforms, e.g., explicit recommendations, implicit social evidence via purchase data, and visibility of peers’ spending patterns [

44]. Generation Z customers’ personal repurchase intentions for certain platforms or items grow markedly when they feel important persons within their reference networks support them [

48].

Where consumption patterns act as vehicles for social communication and group affiliation, this impact is especially noticeable in product categories with high social visibility or identity signaling value [

6]. The social dimensions of consumption are especially important for Generation Z customers negotiating identity construction as they make social influence a key factor in their repurchase choices in social commerce settings [

43]. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H3: Social influence positively impacts Generation Z’s repurchase intention in social commerce.

Facilitating conditions include users’ views on the availability of a technological and organizational infrastructure that supports system use [

23,

49]. For social commerce platforms, these criteria include device compatibility, customer support services, and payment security methods [

50].

Studies show that Gen Z customers, even though they are tech-savvy, are nonetheless aware of the existence of strong enabling factors when deciding to repurchase on social commerce sites [

51]. Users’ trust in platform reliability is greatly increased by the availability of thorough customer support services, safe payment systems, and cross-device capability, therefore reinforcing their repurchase intentions. Meilatinova [

52] underlines the need for several facilitating components in creating consumer trust by saying that building a corporate image is more valuable to strong corporate image retailers while showrooms play a critical role for weak corporate image retailers.

For Generation Z customers in particular, the smooth integration of social commerce platforms with their current technology environment is a particularly relevant enabling factor [

53]. Users feel less friction in transaction procedures when platforms show interoperability with preferred devices, social networking platforms, and payment methods, therefore improving their likelihood of repeat purchase [

30]. Furthermore, for Generation Z customers who appreciate openness and accessibility in their business transactions, the openness of information about accessible assistance resources is a major enabling element. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H4: Facilitating conditions positively impact Generation Z’s repurchase intention in social commerce.

2.4. Signaling Theory and Return Policy Leniency

Signaling theory offers a paradigm for comprehending how parties address in-formation imbalance in market transactions [

69]. Effective signaling systems become very important in social commerce settings when physical product inspection is impractical and vendor authenticity may be questionable for building customer confidence and promoting repurchase behavior [

9]. Of many market signals, return policy leniency has surfaced as a particularly strong tool for lowering perceived risk and improving buying intentions [

12].

Return policy leniency is the degree of flexibility and ease of the return process of the vendor’s product, including time frame allowances, reimbursement assurances, and procedural simplicity [

70]. Lenient return policies act as trust signals that reduce doubts about product quality and vendor dependability for Generation Z customers negotiating social commerce settings [

71]. Studies show that, when online retailers adopt a lenient return policy, consumers have higher perceived quality and lower perceived risk, which in turn leads to a higher intention to purchase [

72]. In the setting of recurrent purchase choices, when customers’ previous encounters with return procedures greatly affect their readiness to participate in following transactions, this signaling mechanism becomes more important [

73].

Return policy leniency is especially important for Generation Z customers, who show more risk sensitivity in digital buying settings, as a strong predictor of their repurchase intentions [

8]. Knowing that undesired purchases may be undone with few financial or procedural repercussions greatly lowers perceived transaction risks, hence increasing the likelihood of these customers making repeat purchases [

74]. In product categories marked by changeable quality, size uncertainty, or subjective assessment criteria, the link between return policy leniency and repurchase intention intensifies [

75]. In such situations, Generation Z consumers, when considering recurrent purchases, find risk reduction tools especially useful in forgiving return policies [

76]. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H8: Return policy leniency positively impacts Generation Z’s repurchase intention in social commerce.

Online trust among Generation Z customers in social commerce settings seems to considerably moderate the link between return policy leniency and repurchase intention [

77]. This mediation mechanism signals vendor dependability and product quality via permissive return policies, hence fostering confidence that finally enhances repurchase intentions [

75].

Studies show that firms signal trustworthiness through transparent business practices [

70], with return policy leniency being an especially obvious example of such openness. Generous return policies provide credibility signals for Generation Z customers negotiating information asymmetry issues in social commerce settings, hence improving views of vendor trustworthiness [

71]. This increased confidence then lowers psychological obstacles to repurchase, hence promoting customers’ readiness to participate in many transactions with certain vendors [

9].

In cross-border e-commerce settings, when geographical distance increases information asymmetry worries, the mediating function of online trust becomes clearer [

78]. International sellers that use lax return policies show dedication to client happiness despite logistical issues, hence greatly boosting confidence among Generation Z customers [

79]. Shao and Chen [

80] point out that, when a consumer purchases a product that ships from a domestic bonded warehouse or a product without a product traceability code present, the effect of the leniency of the return policy on perceived quality and perceived risk is stronger, stressing contextual elements affecting this mediation link.

The trust-building role of return policy leniency is especially important for Generation Z customers, who show more skepticism towards unknown internet businesses [

81]. When these customers see lax return policies as signs of vendor confidence and dependability, the ensuing trust greatly increases their likelihood of platform reengagement and repeat buying behavior [

9]. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H9: Online trust positively mediates the relationship between return policy leniency and repurchase intention in social commerce.

From the research hypotheses above, this study proposed the research model shown in

Figure 1.