1. Introduction

In recent years, China’s digital transformation has been deepening, the foundation of industrial transformation has become more consolidated, the innovation and development system has become more sound, the digital transformation of enterprises has continued to steadily advance, and the practice of transformation exploration has advanced to a higher level due to the growing application of new-generation information technology, such as cloud computing, artificial intelligence, big data analysis technology, intelligent Internet of Things systems, blockchain, etc. China has successfully accelerated the growth of its new quality productivity and established a benign interactive development pattern by promoting the iterative upgrading of its digital industrial ecology and the digital reconfiguration of production variables in a synergistic manner. According to the China Communications Research Institute’s Research Report on the Development of China’s Digital Economy (2024) [

1], the GDP share of China’s digital economy increased by 1.3 percentage points to 42.8% in 2023, with a nominal year-over-year growth rate of 7.39%, which was higher than the GDP growth rate during the same time period.

It may be said that corporate innovation is the result of information sharing across various subjects, and in the setting of digitalization, consumers, suppliers, investors, and so forth have become significant participants in the process of product creation and production [

2]. In the context of market competition, enterprise innovation ability refers to an organization’s overall capacity to engage in innovative activities and attain outcomes in product, technology, management, marketing, and other areas through the efficient integration of internal and external resources [

3]. Businesses must keep innovating and putting more of a focus on technology if they want to survive in the face of intense market competition. Then, how precisely does the digital transition affect businesses’ capacity for innovation?

Currently, the academic community’s research on enterprise innovation and digital transformation has produced step-by-step findings. In order to further increase stock liquidity and create a better market environment for corporate innovation [

4], enterprise digital transformation can firstly increase the capital market’s information transfer efficiency [

5], remove information barriers, and boost investors’ confidence in their investments [

6].

Second, when it comes to profitability, the extensive use of information technology alters the management paradigm and innovation mode of the business, enhances the management and monitoring capabilities of internal organization operations, and fortifies the resource configuration and accuracy of enterprise innovation activities [

7]. Innovation mode, which strengthens the enterprise’s capacity to allocate resources and make accurate decisions, improves the management and monitoring of internal organization operations, and boosts production efficiency [

8]. These factors allow the corporate to win in market competition, increase its profitability, and provide financial support for its innovation. In terms of corporate governance, digital transformation helps to optimize the organizational structure [

9], enhance the ability to integrate resources, and streamline operations. Resource integration capabilities and streamline operations [

10], boosting the competitive advantages and governance efficacy of businesses and creating a favorable internal environment for corporate innovation.

Digital transformation also includes the alteration of informal systems like organizational culture, in addition to the widespread use of digital technology and the reform of internal formal structures [

11]. The values and characteristics of a corporate that are developed via long-term practical actions and that are embraced and implemented by the organization’s internal members are known as corporate culture. The development and advancement of technology is not the only factor that determines the success of digital transformation; corporate culture, particularly corporate innovation and cooperative culture, is crucial [

12]. As per the current scholarly research, data are the primary component of digital transformation in the big data era. Processing big data necessitates teamwork and information sharing, which calls for the preservation of a cooperative culture [

13]. While the innovation culture is a key internal driver of innovative vitality within the company, the enterprise digital transformation is also a significant manifestation of the growth of corporate innovation culture. Thus, corporate culture is the foundation of corporate development, corporate collaborative culture emphasizes resource integration and synergy, and innovation culture fosters breakthroughs and trial-and-error tolerance, all of which contribute to an organization’s capacity for innovation in different ways [

14].

In summary, the majority of research has examined the benefits of digital transformation for businesses’ innovation performance, management effectiveness, and profitability. Nevertheless, there are still three areas where the literature is lacking: first, it mostly overlooks the important informal institutional variable of corporate culture, particularly the path of collaborative culture and innovation culture; it focuses on studies at the macro- or industry-level; and it pays little attention to the mechanism of the distinct institutional structure of China’s emerging markets on the relationship between innovation and digitalization. Second, the majority of the literature currently in publication concentrates on studies conducted at the macro- or industry-level, with little research conducted at the micro-firm level; third, there is a dearth of research on the mechanism by which China’s new market-specific institutional structure influences the relationship between innovation and digitization in businesses. To address the theoretical and empirical gaps of previous research, this paper builds a mechanism model of “digital transformation-corporate culture-innovation capability” from the perspective of cultural capital and empirically tests it using panel data of Chinese A-share listed companies. Theory and empirical data from previous research are reconciled.

This study will use a fixed effects model to analyze the mechanism of digital transformation’s impact on firms’ innovation capability using data from China’s A-share listed companies from 2012 to 2021. The Tobit model and instrumental variable method will be used to test the validity of the research hypotheses in this paper. The conclusions are constrained by the unique institutional framework, market, and social environment in China. It should be mentioned that the primary emphasis of this paper’s research is the data of China’s A-share listed businesses from 2012 to 2021. Consequently, the conclusions of this article may not be externally generalizable in other nations and areas. China was chosen as the research object for three main reasons: first, it is one of the nations with the fastest and largest pace of digital transformation in the world; second, it has proposed numerous policies and useful programs in the process of digital transformation, such as the “14th Five-Year Plan”; and third, its digital economy accounted for 42.8% of GDP in 2023, providing a rich and diverse research sample for this study. The “14th Five-Year Plan” for the development of the digital economy and the overall layout plan for the construction of Digital China are just two examples of the many practical programs and policies China has proposed in the process of digital transformation. These initiatives provide enough empirical soil for this study to explore the mechanism of “technology-culture-innovation.” China, being the largest developing country in the world, faces many challenges in the process of digital transformation. As the largest developing nation in the world, China is a good example of the institutional and humanistic contexts it encounters during the digital transformation process. This can serve as a model for other emerging market nations or economies undergoing digital transformation. Given the foregoing context, this study’s findings may not be as generalizable in other nations, but they nevertheless have significant theoretical and empirical significance.

This paper is structured as follows: the introduction comes first, followed by the theoretical background and research framework in the second part, the research hypotheses in the third part, the research design in the fourth part, the empirical analysis in the fifth part, the mechanism of action in the sixth part, the analysis of heterogeneity in the seventh part, the conclusions in the eighth part, and the revelations in the ninth part.

2. Theoretical Background and Research Framework

Resource-based theory and dynamic capabilities theory serve as the foundation for this paper’s theoretical approach.

Resource-based theory states that the three primary characteristics of an enterprise’s resources—scarcity, inimitability, and non-substitutability—are essential for gaining and preserving a competitive edge [

15]. The essential characteristic of corporate cultural capital is the culture of collaborative and innovation, which is considered a significant “soft resource” within this theoretical framework and has a beneficial impact on an organization’s innovative performance. As the digital transformation accelerates, dynamic capability theory notes that in order to maintain an organization’s innovation performance, it must have the “sense-capture-reconfigure” capability chain to realize the dynamic integration and reconfiguration of internal and external resources in the face of a highly uncertain and rapidly changing external environment. Reconfiguring and dynamically integrating external and internal resources boosts competitiveness over time [

16]. The widespread use of digital technology in this process not only gives businesses a better ability to perceive their surroundings and a more effective way to gather information, which helps them spot market shifts and new opportunities for innovation quickly, but it also opens up new avenues for corporate culture evolution and reshaping [

17].

In particular, the use of digital technology has altered how businesses communicate, collaborate, and work together. It has also altered the values and standards of behavior of those who work for these companies. For instance, effective cross-departmental collaboration and information flow mechanisms based on digital platforms help to improve teamwork efficiency, dismantle information silos, and strengthen the corporate collaborative culture [

18]. At the same time, digital technology’s data-driven decision-making and quick trial-and-error mechanism further encourage the development of an organization’s more open and inclusive innovation culture. The cultural foundation for innovation activities is further strengthened by this digital technology-driven cultural shift.

Innovation culture encourages organizational members to take chances, accept failures, and foster an environment of active exploration and ongoing trial and error, which further stimulates the innovation subjectivity of organizational members [

19]. Collaboration culture helps dissolve internal boundaries of the organization, strengthens internal collaboration and external collaboration, and improves the efficiency of resource sharing and information flow [

20]. For businesses undergoing digital transformation, the synergistic effect of collaborative and innovation cultures creates a highly adaptable cultural system that fortifies the organizational culture for resource reconstruction and capability upgrading and encourages businesses to achieve innovation breakthroughs and sustainable development in the wave of digitalization.

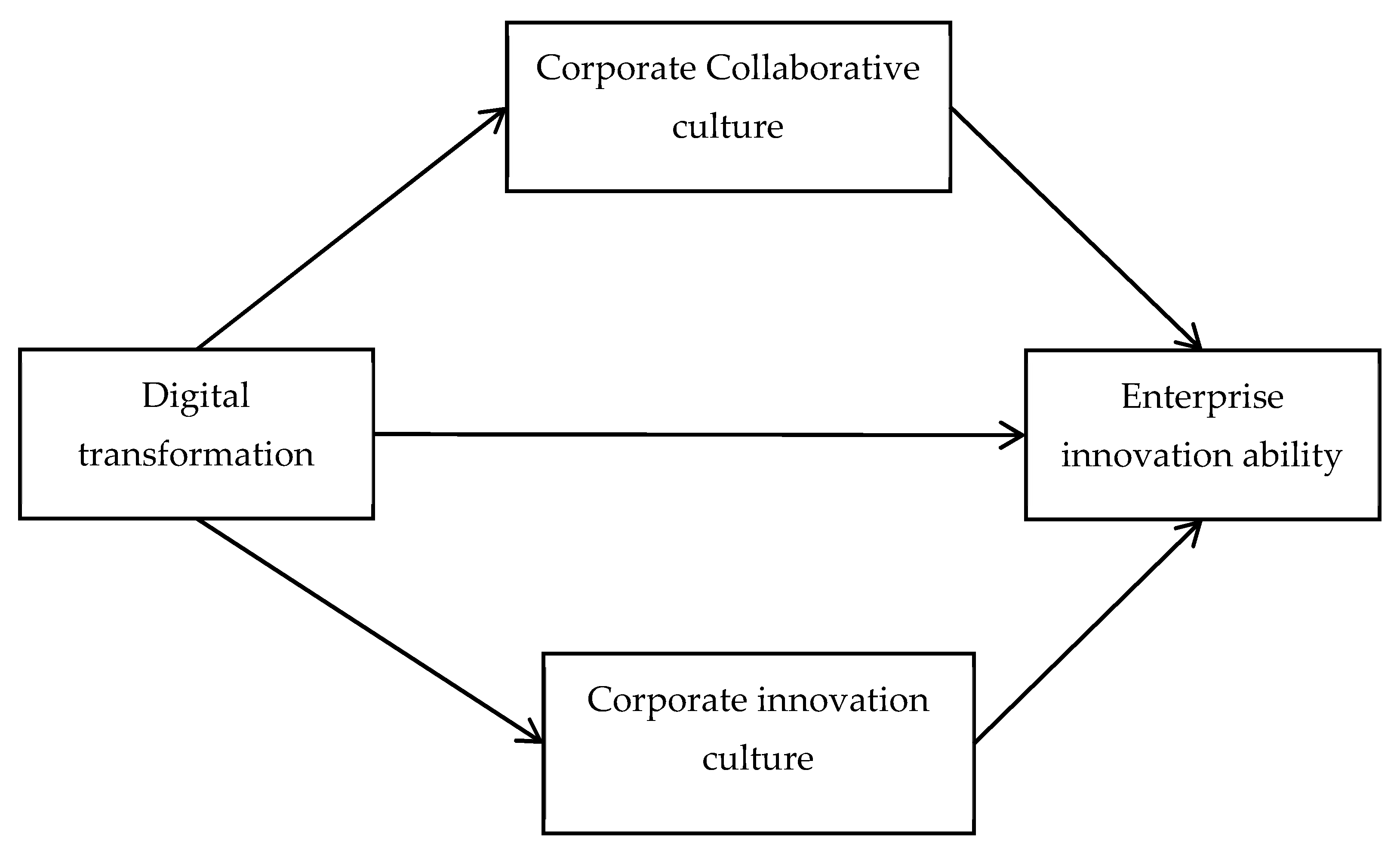

In summary, this paper develops a theoretical framework of “technology-culture-innovation” based on dynamic capability theory and resource-based theory. It uses corporate innovation and collaborative cultures as mediating variables to investigate the mechanism of influence between corporate innovation performance and digital transformation. The specific theoretical models are illustrated in

Figure 1.

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Digital Transformation and Corporate Innovation Capabilities

The use of digital technology facilitates the development of an intelligent, digital supply chain that includes consumers, workers, and outside investors. This allows them to participate in the production and operation of the business, increasing information sharing efficiency and facilitating smooth collaboration [

21].

First, from the perspective of corporate governance, the digitization and automation of enterprise production and services through digital transformation will undoubtedly reduce some simple and repetitive work within the enterprise, increase the scale of data application, and create a collaborative management and decision-making mode between humans and machines [

22]. This will make the enterprise’s internal management smarter, effectively reduce the phenomenon of self-interestedness and procrastination of the management of the enterprise and improve the enterprise’s overall operational capability. It can enhance the enterprise’s overall operating capability and successfully lower the likelihood of self-interest, delays, and other management issues [

23]. Second, in terms of human capital, businesses undergoing digital transformation keep developing a creative talent system that aligns with the digital strategy. Through organizational training, job restructuring, and talent introduction, internal members of the organization’s digital skills and technological adaptability are continuously improving, with the goal of promoting enterprise innovation and providing intellectual protection for technological development, product design, and service innovation [

24]. Last but not least, digital technology gives businesses access to more intelligent and practical data platforms and infrastructure, which lowers the cost of trial and error for innovation and offers a strong material basis for business model innovation, product iteration, and technology development [

25].

First, as seen from the outside of businesses, the platform for enterprise interconnection created by utilizing digital and Internet technologies allows businesses in the industrial chain to collaborate in creating digital ecological clusters and offers hardware and software support for business innovation. The creation of digital ecological clusters also includes third-party technical institutions, such as colleges and universities, scientific research institutions, etc., which can help to promote the exchange and collaboration among enterprises, provide intellectual support for corporate innovation, and enhance the collaborative innovation ability of enterprises. On the one hand, this can provide a platform for information exchange and cooperation among enterprises [

26], accelerate information and technology sharing among enterprises [

27], and thereby increase the innovation enthusiasm of enterprises. However, the creation of digital eco-clusters also incorporates outside technology institutions like research institutes and universities, which fosters collaboration and exchanges between businesses, offers intellectual support for corporate innovation, and strengthens the capacity for collaborative innovation within the enterprise. Second, digital transformation can lower the cost of buyers’ information searches, produce positive information spillover effects, and further increase the level of information disclosure of supplier firms [

28]. To ensure the financial needs of innovation activities, it can, on the one hand, lessen the degree of information asymmetry between the company and external investors, provide a positive corporate image for the company, and assist the company in obtaining more financial support [

29]. On the other hand, supplier enterprises can more quickly obtain and master the market demand for resources, allowing them to more accurately invest in and develop new areas, and improve the matching between enterprise R&D and market demand. However, supplier businesses can acquire and understand market demand resources faster, which allows them to invest and develop new areas more precisely and enhances the alignment of company R&D with market demand [

30]. A favorable institutional environment for enhancing businesses’ capacity for innovation and digital transformation is also provided by the development of digital infrastructure, enhanced policy support, and improved regulatory mechanisms at the national level [

31].

As a result, this paper puts forth the following theories:

H1: Digital transformation makes it easier for businesses to improve their capacity for innovation.

3.2. Digital Transformation, Corporate Collaboration Culture and Corporate Innovation Capability

The value orientation of coordinating and exchanging resources and expertise among members of the enterprise, as well as exchanging resources and looking for win-win situations among enterprises outside the enterprise, is referred to as enterprise collaborative culture [

32]. According to this study, digital transformation primarily strengthens an organization’s capacity in these three areas and, by utilizing the soft capabilities of cooperative culture, further strengthens an organization’s capacity for innovation [

33]. The primary impact pathways are as follows:

The internal organization of the company will continue to flatten and grid as the degree of enterprise digitalization increases. This helps encourage the creation of cross-functional departments within the company, which will increase the amount of technology and information sharing within the company and lessen information asymmetry [

34]. At the same time, the company will also gradually create a network of collaborative office platforms. This kind of instantaneous, open online information sharing platform can help transfer pertinent information to the various functional departments of the company in a timely and accurate manner, breaking down the time and space constraints of information communication and significantly lowering communication costs. It also partially facilitates the integration of heterogeneous resources, improves collaboration efficiency, and fosters unity and cohesion amongst the company’s employees, all of which contribute to a more cooperative corporate culture. So strengthening the cooperative corporate culture [

35]. In addition to being sensitive to the perception of opportunities for market development both internally and externally, cooperative cultures can effectively dismantle organizational barriers, encourage the sharing of resources and information, foster the development of high-quality composite talents, strengthen teamwork, and offer intellectual support for the creative exploration of novel opportunities [

36].

Externally, the use of digital technology has made it possible for businesses to construct digital ecological clusters, which offer venues for fostering corporate collaboration [

37]. The creation of these online platforms has improved information sharing among businesses [

38], which can help alleviate the phenomenon of information asymmetry among businesses [

39]. Private information that is hard to observe, like price, demand level, product quality, and effort, has been transformed into shared information. On the one hand, the creation of digital ecological clusters facilitates direct communication between upstream and downstream businesses, which can effectively lower communication costs and increase the willingness of upstream and downstream businesses to cooperate; on the other hand, supply chain businesses can swiftly gather pertinent information when consumer demand shifts, allowing them to shift the focus of research and development and innovation and look for new, distinct market competitiveness [

40]. Last but not least, a robust culture of collaboration among businesses can raise the degree of trust and group willingness to innovate. At the same time, it can improve the ability of businesses to collaborate on research and development and react swiftly to market developments, which will raise the level of innovation across the board [

41].

As a result, this work is predicated on the following assumptions:

H2: By altering the corporate collaboration culture, digital transformation enhances business creativity even more.

3.3. Digital Transformation, Corporate Innovation Culture and Corporate Innovation Capabilities

A company’s culture that encourages people to try new things, think outside the box, and take chances is known as its corporate innovation culture [

42]. Technology improvements brought forth by digital transformation give businesses a lot of help in rebuilding internal procedures and allocating resources as efficiently as possible. But depending solely on technology empowerment won’t provide you a sustained competitive edge; innovation culture is also a “soft resource” that must be supported. This essay makes the case that innovation culture serves as a crucial link between business innovation capabilities and digital transformation.

First, geography and industry will always have an impact on competition between traditional businesses. However, as digital technology has advanced and become more mature, the trend of cross-border operations and enterprise integration has become more evident, and competition between businesses has increased [

43]. To improve their ability to deal with the uncertainty of the factors of the last name, which may allow them to stand firm in the fierce competition in the market, companies that were once at the top of the digital market are also gradually losing their unique competitive advantages. As a result, they have started to introduce new digital technologies, strengthen the importance of the innovation culture, and cultivate innovative talents [

44]. Companies that promote a culture of innovation tend to develop an atmosphere that encourages change and supports risk-taking and innovation, and this atmosphere can give employees the psychological security to explore new ideas, thoughts, and products without fear of failure in the face of uncertainty and risk [

45]. At the same time, a climate of innovation within an organization will also lessen the reluctance of organizational members to change, thereby improving the general desire to innovate within the organization [

46].

Second, the adoption of new technologies brought about by digital transformation increases business productivity [

47], further optimizes the industrial structure of businesses, and makes innovation results visible, all of which encourage employees to innovate and support the growth of business innovation cultures [

48]. Simultaneously, the innovation culture fosters cooperation, tacit knowledge transfer, and employee exploration of informal resources, all of which can improve the organization’s awareness of its resources and its capacity for dynamic reconfiguration [

49]. Furthermore, businesses can flexibly control resource allocation through digital technology platforms, creating a more comprehensive system and offering better resources to encourage technological innovation [

50].

Third, both corporate innovation and digital transformation have lengthy cycles and high risks. To develop, they need the backing of advanced technology, robust capital, and highly skilled innovative personnel, in addition to the willingness of employees to work for the company. The use of digital technology improves supply chain firms’ transparency and collaboration efficiency while also successfully reducing information asymmetry between them [

51]. By encouraging collaboration, creativity, and resource sharing across businesses, this method helps to build innovation ecosystems and strategic alliances, which raises the industry’s degree of innovation overall [

52].

In conclusion, innovation culture is a key factor in helping an organization create a sustainable competitive advantage because it not only creates a favorable environment for innovation within the company but also enhances the benefits of digital transformation on the company’s capacity for innovation by fostering psychological security, encouraging resource allocation, and fostering cooperative synergy.

As a result, this work is predicated on the following assumptions:

H3: By altering the company’s innovation culture, digital transformation improves corporate innovation even more.

4. Research Design

4.1. Data Sources

Chinese A-share listed businesses were chosen for this paper’s panel data construction from 2012 to 2021, with the majority of the relevant data coming from the CNRDS and CSMAR databases as well as company annual reports.

4.2. Variable Settings

4.2.1. Explained Variable

Corporate innovation capability is the paper’s explained variable. The amount of patent applications is the primary indicator of the innovation performance of listed businesses, according to the literature currently in publication. The number of invention patents can be a good indicator of an organization’s capacity for innovation because it takes a long time for patents to be authorized, and the authorization procedure is susceptible to uncertainty-type factors. As a result, this study uses the number of invention patents that a company grants annually as a measure of its capacity for innovation in the current year. It then applies logarithmic treatment after adding 1.

4.2.2. Explanatory Variable

The extent of enterprise digital transformation serves as this study’s explanatory variable. The degree of enterprise digital transformation will be measured in this research using text analysis, by Song HS et al.’s (2025) [

53] methodology, The following are the precise steps: Making a dictionary of keywords was the first stage. The following keywords were found after carefully extracting and organizing the keywords: artificial intelligence, artificial intelligence, digital economy, and digital economy. The keywords used in this study were primarily taken from several references on digital transformation [

54,

55,

56], as well as the “14th Five-Year Plan” and “Research Report on the Development of China’s Digital Economy” published by the Chinese Government Network [

57]. AI, business intelligence, blockchain technology, machine learning, deep learning, big data technology, data mining, mobile payments, Internet healthcare, e-commerce, smart wearables, smart platforms, B2B, B2C, C2B, C2C, digital marketing, etc. were among the keywords that have been identified. The second phase involved organizing and analyzing the pertinent phrases from annual reports. The Python 3.12.3 crawler function was used in this study to read MD&A keywords and calculate word frequency statistics. The following justifies the selection of the enterprise annual report for text analysis in this paper: An essential source of information that businesses must disclose in compliance with the law, enterprise annual reports are highly authoritative and credible. They cover a wide range of topics, including financial performance, operating conditions, and future planning, among others, and offer a wealth of data for methodical analysis of enterprise digital transformation. The third was the development of indicators. In this study, the word frequency was considered as the extent of the enterprise’s digital transformation in the year after adding 1 to take the logarithm of the word frequency to overcome the proper bias of the data.

4.2.3. Intermediary Variable

Corporate collaborative culture (CCC) and corporate innovation culture (CIC) are the mediating variables in this study. This essay examines business annual reports using text analysis. Making a dictionary of keywords was the first stage. The following keywords were ultimately identified after the Word2Vec word vector model was used to expand the keyword lexicon in conjunction with the relevant literature of Yanyan Wang et al. (2024) [

58]: collaboration, trust, solidarity, responsibility, cooperation, win-win, sharing, respect, mutual aid, cross-functional collaboration, strategic alliance, etc. are the keywords used to identify the cooperation culture; innovation, development, research and development, creation, invention, adventure, trial and error, disruptive innovation, etc. were the keywords used to identify the innovation culture. Analyzing and classifying the MD&A-related terms was the second phase. The Python 3.12.3crawler function was used in this study to read MD&A keywords and calculate word frequency statistics. The construction of indicators was the third phase. The word frequency was multiplied by one in this study to determine the logarithm of the word frequency, which represents the extent to which businesses this year are fostering an innovative and collaborative culture.

4.2.4. Control Variable

The control variables used in this study are listed in

Table 1.

4.3. Model Setup

This study builds a panel data model (1) and conducts an empirical analysis to determine if corporate innovation culture and corporate collaborative culture are impacted by digital transformation.

where u

t stands for the time fixed effect, vide for the industry fixed effects, and ε

i,t for the randomized disturbance term. The explained variable capability is the corporate innovation capability, and digital indicates the extent of the firm’s digital transformation. The variable control indicates many control variables, such as the firm’s age, size, property rights, gearing ratio, net asset margin, proportion of independent directors, and the proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder.

In this paper, the Hausman test was employed to decide whether to utilize the fixed effects model or the random effects model.

Table 2 displays the test results. The initial hypothesis was rejected by the

p-value of 0.000, which is less than the significance level of 0.05. This suggests that the fixed effect model is a better fit. Consequently, the fixed effect model served as the foundation for the empirical study that follows in this paper.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

The following guidelines were used in this paper to filter the preliminary samples: In order to mitigate the effects of outliers, this paper shrunk all continuous variables at the 1% and 99% deciles. Ultimately, a total of 18,239 samples were obtained, and descriptive statistics of the variables are displayed in the table. Financial industry, ST or *ST, and samples with significant missing data were excluded. The results of the descriptive statistical analysis are shown in

Table 3.

5.2. Correlation Coefficient Analysis

This research goes on to create a correlation coefficient matrix for the first testing to better understand the relationship between the variables. According to

Table 4’s findings, corporate innovation capabilities and the level of digital transformation have a strong and positive correlation. This suggests that corporate innovation may be encouraged by digital transformation. Furthermore, a significant correlation coefficient between firm size and corporate innovation capability suggests that an organization’s capacity for innovation may be higher the larger it is. Notably, some of the control variables also have large correlations with one another. For instance, the corporate size and corporate gearing ratio correlation coefficient is as high as 0.526 (

p < 0.1), indicating that multicollinearity may be an issue. Consequently, the multicollinearity test is carried out in the next section of this study.

5.3. Multicollinearity Test

In this study, the presence of multicollinearity in the model is further tested based on correlation analysis results. Each explanatory variable’s variance inflation factor (VIF) is determined in this study. All of the variables’ VIF values are less than 5, as

Table 5 demonstrates, suggesting that multicollinearity is not a significant issue and that the model’s regression findings are reliable.

5.4. Base Regression Analysis

In this study, the benchmark regression analysis begins after the absence of multicollinearity between variables has been ruled out. Using regression models,

Table 6 investigates how enterprise digital transformation affects corporate innovation capabilities. The innovation capacity of businesses is significantly positive at the 1% level when time fixed effects and industry fixed effects are the only factors controlled for in the first column. The results are still strong when control variables are added in the second column, despite the correlation coefficients being lower. This implies that increasing a company’s capacity for innovation is facilitated by digital transformation. The first hypothesis is confirmed.

5.5. Robustness Check

To verify the reliability of the benchmark regression results, this paper further conducts robustness tests.

5.5.1. Endogenous Issues

In this paper, the endogeneity problem is analyzed from two main aspects, as follows:

This research employs the instrumental variable approach to perform the stability test to mitigate the issue of endogeneity in the influence of digital transformation on corporate innovation capacity. This paper uses the lagged one period of the degree of enterprise digital transformation in the sample data as the instrumental variable of the panel data because we believe that the degree of enterprise digital transformation is endogenous and that the degree of enterprise digital transformation in the current year will have an impact on corporate innovation capacity in the following year.

Table 7 displays the estimation outcomes of the two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach. The first stage’s results demonstrate that the instrumental variable is significantly and positively related to the firm’s degree of digital transformation in the previous year, with an F-statistic of 7573.449, which is significantly larger than 10 and indicates that there is no weak instrumental variable problem. The second stage’s results demonstrate that the enterprise innovation capability is positively impacted by the degree of digital transformation of the firm lag one period, with a coefficient of influence that is still significantly positive, indicating that even after accounting for endogeneity issues, the firm’s digital transformation continues to positively contribute to corporate innovation capability.

Referring to the research methodology of Qiaoling Fang et al. (2024) [

59], this paper uses the average culture value of excluding itself at the industry-year level as an instrumental variable in light of the potential endogeneity problem of corporate culture variables. The two-stage least squares (2SLS) method was used to estimate the collaborative culture and innovation culture independently. The industry-year level, excluding its average culture value, was chosen as an instrumental variable for this paper for the following reasons: it can reflect the industry cultural atmosphere that the enterprise faces, which will influence the formation of the enterprise’s own culture, but it has no direct impact on the enterprise’s output of innovation, and it satisfies the correlation and exclusion line assumptions of the instrumental variable.

The F-values of the instrumental variables for cooperative culture and innovative culture are 5450.08 and 2214.68, respectively, which are significantly larger than 10, and the level of significance passes the 1% test, indicating that the instrumental variables are more powerful. The first stage results demonstrate a high correlation between instrumental and endogenous variables. In support of the research hypothesis of this paper, the second-stage results (e.g.,

Table 8) demonstrate that the impact coefficients of innovative culture and cooperative culture on corporate innovation capability are 0.607 and 0.355, respectively, and that both are significantly positive at the 1% level. This research uses heteroskedasticity-resistant standard errors to ensure robustness.

Table 9 displays the R2 when utilizing robust standard errors, which further confirms the validity of the regression results.

5.5.2. Tobit Model

This paper uses the Tobit model to examine the robustness of the samples since the explained variables and the explanatory variables in this paper are both continuous positive distributions with 0 as the lower limit and clear left truncation characteristics. With a regression coefficient of 0.273 and a standard error of 0.0078, the study’s findings demonstrate that enterprise digital transformation significantly improves corporate innovation capability. According to the Tobit marginal effect, the enterprise’s innovation capability increases by 0.273 units (p < 0.01) for every unit increase in the digital transformation index. This is significant and has positive economic significance. The likelihood ratio test yielded a statistic of 34.58, which is less than 0.0001, indicating that the model’s overall fitting effect is better and that the independent variables included can better explain the variation of the dependent variable. As a result, the research content of this paper is still valid.

5.5.3. Excluding Some Samples

As can be seen from

Table 3’s descriptive statistics, there is a significant difference in the ability of the samples chosen for this paper to innovate. The high-tech industry has a higher ability to innovate, and its capital, talent, and other resources are better equipped than those of other industries, whereas the non-high-tech industry has a lower ability. Excluding industries with more innovation capabilities further strengthens the results’ robustness. The manufacturing of pharmaceuticals, electronics, novel materials, and aerospace is all classified as high-tech industries in this research and is therefore not included. As shown in column 1 of

Table 10, the correlation coefficient between digital transformation and innovation capability is still positive after excluding some samples, and the results are still robust.

5.5.4. Change the Way the Degree of Digital Transformation of Enterprises Is Measured

In addition to being one of the results of a company’s digital transformation, intangible digital assets will also, to some degree, enhance an organization’s capacity for creativity. We will now use the ratio of intangible digital assets to intangible assets in the enterprise as a measure of the degree of enterprise digital transformation.

Table 11 is the outcome of a descriptive statistical analysis of intangible digital assets. The aforementioned benchmark regression analysis measures the degree of enterprise digital transformation using text analysis on the enterprise’s annual report in the relevant year. The correlation coefficient matrix for intangible digital assets is displayed in

Table 12. The variance inflation factor was further analyzed in this work to address the multicollinearity issue. The mean value of the VIF for all variables is less than 5, indicating that multicollinearity is not an issue.

In order to test for robustness, intangible digital assets were included as a new explanatory variable to the regression model. The results, which are displayed in

Table 10’s second column, indicate that the study hypotheses remain true and that the correlation coefficients between the two variables are positive.

6. Analysis of Mechanisms of Action

The aforementioned empirical findings support the paper’s hypothesis H1, and this chapter will confirm if organizational digital transformation fosters creativity and collaboration by affecting these cultures. This chapter includes two mediating variables, corporate collaborative culture and corporate innovation culture, for stepwise regression analysis to methodically confirm the plausibility of the hypotheses. Additionally, 500 Bootstrap replicated sampling was used to confirm the significance of the mediating effect in the following ways:

The enterprise digital transformation will have a positive impact on the corporate collaborative culture, as indicated by the regression coefficient of the degree of digital transformation on the corporate cooperation culture of 0.150, which passes the significance level test of 1% (see column 2 of

Table 13). In contrast, column 4 shows that the coefficient of the effect of digital transformation on the corporate innovation capability decreases when the corporate collaborative culture is included, but the result is still significant. At the same time, 500 Bootstrap repeated samples were used to estimate the mediation path’s confidence intervals. The 95% confidence interval does not contain 0, according to the Bootstrap test results, indicating that the mediation effect is significant. This implies that the hypothesis H2 is correct, as the degree of digital transformation of businesses can improve their capacity for innovation by influencing their growth to prioritize the establishment of a corporate cooperative culture.

According to

Table 13’s column 3, the degree of enterprise digital transformation has a positive impact on corporate innovation culture, as evidenced by the regression coefficient of the degree of enterprise digital transformation on corporate innovation culture of 0.133, which passes the 1% significance level test. Similarly, column 5 shows that the influence of the degree of enterprise digital transformation on corporate innovation capability decreases when corporate innovation culture is included, but the results remain strong. In the meantime, 500 Bootstrap repeated samples are used to estimate the mediation path’s confidence intervals. The 95% confidence interval does not contain 0, indicating that the mediation effect is significant, according to the Bootstrap test results. The hypothesis H3 is valid because it implies that the degree of digital transformation of businesses can have an impact on their capacity for innovation by influencing their development to prioritize the development of corporate innovation culture.

7. Heterogeneity Analysis

In actuality, the internal and external environments of the area in which the businesses are situated will have distinct effects on the corporate innovation made possible by digital transformation. Three factors were used in this study to examine the sample’s heterogeneity: sample ownership, the level of industry competitiveness, and the sample’s level of technical progress.

7.1. According to the Nature of Ownership of the Sample

To further investigate the validity of the hypotheses presented in this work, the enterprise type was separated into two groups: state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises. Depending on the type of business, the state that owns more than 50% of the business or does not own it but has real influence over it was classified as a state-owned business, while the remaining businesses were classified as non-state-owned businesses.

Table 14 illustrates that the degree of digital transformation of state-owned businesses has a greater effect on their capacity for innovation than does the degree of digital transformation of non-state-owned businesses at the same time. This suggests that state-owned businesses typically possess monopoly power, have more resources available for innovation, and are naturally better suited to engage in innovative activities. However, non-state-owned businesses might encounter a lack of funding, technology, and skilled personnel during the innovation process, which would limit their capacity to develop independently.

7.2. Based on the Level of Competition in the Industry

This study makes the case that an organization’s capacity for innovation will be influenced to varying degrees by the level of competition in the sector in which it operates. The industry as a whole can be separated into monopoly and non-monopoly sectors based on the level of industry competition. Agriculture, manufacturing, retailing, catering, and the Internet are examples of non-monopoly businesses, whereas petrochemical, train transportation, electronic information, aerospace, and tobacco are examples of monopoly industries. While the non-monopoly industry will face more intense market competition and must innovate to increase its strength to obtain more profits and market share, the monopoly industry generally has less market competition and a relatively poor sense of independent innovation. Businesses often prefer to maintain the current market position and level to obtain revenue.

Table 14 shows that while there is a positive correlation between the two, the impact of digital transformation on the innovation capacity of businesses in monopoly industries is slightly smaller than that of businesses in non-monopoly industries.

7.3. Depending on Whether the Sample Is in a High-Tech Industry

This study distinguishes between high-tech and non-high-tech industries based on the industry’s capacity for innovation. It assumes that the former includes the Internet, electronic information, and other related sectors, while the latter includes non-high-tech industries. The high-tech industry typically invests a lot of R&D funds in innovation, which can improve the financial support for corporate innovation; at the same time, the industry has more innovative talent, which can improve the intellectual and technical support for corporate innovation; and lastly, the high-tech industry has a faster rate of technology dissemination, emphasizing collaborative innovation. The creation of new technology can be swiftly applied and spread within the industry, which promotes innovation and upgrades the entire industry. Furthermore, the non-high-tech sector is constantly increasing its investment in corporate innovation to better compete in the market and keep up with the rate of market upgrading. The aforementioned theory is still true, as

Table 14 demonstrates that the digital transformation of both high-tech and non-high-tech industries will positively impact businesses’ capacity for innovation.

8. Conclusions

This article empirically examines the relationship between enterprise digital transformation and corporate innovation capability, as well as its mechanism, using data from China’s A-share listed corporations from 2012 to 2021. A theoretical explanatory framework and empirical analysis for the synergistic framework of “technology—culture—innovation” are provided, and it is discovered that the impact of digital transformation on businesses roughly follows the path of “digital technology—cultural capital—corporate innovation.” This approach compensates for the shortcomings of “technological determinism” in the literature that is currently available. It fills in the gaps left by “technological determinism” in the literature and offers an empirical analysis and theoretical explanatory framework for the “technology-culture-innovation” synergy framework.

First, through a variety of methods, digital transformation strengthens businesses’ ability to innovate. Externally, the development of digital ecosystems has encouraged strategic synergies and resource complementarities among enterprises, creating an external environment that fosters innovation. Internally, digital technology has increased the intelligence of management processes, the efficiency of enterprise resource allocation, and the degree of information sharing.

Second, an essential bridge connecting innovation and technology is cultural capital. In addition to altering the technological underpinnings of businesses, digital technology has also impacted organizational culture, particularly the collaborative and innovative culture. This study, which is based on resource-based theory and dynamic capacity theory, considers culture as the “lubricant” between innovation and technology. It also reveals the “technology → culture → capability” transmission chain and enhances the understanding of the significance of informal systems in digital transformation.

Third, there is notable variation in the innovation effect between market and institutional contexts. Due primarily to their scale advantage and access to policy resources, SOEs have a stronger innovation-driving effect from digital transformation than non-SOEs. In non-monopolized industries, the effect is more pronounced, supporting the expected “competitive pressure-innovation incentive” theory; in high-tech industries, the high degree of complementarity between digital technology and knowledge assets further increases the effectiveness of innovation. The high degree of complementarity between intellectual assets and digital technology further boosts innovation effectiveness in high-tech enterprises.

To investigate how businesses alter their internal informal systems during the digital transformation process and how this impacts their capacity for creativity, this study begins from the micro perspective and ingeniously adds the mediator variable of company culture. To compensate for the limitations of the dualistic framework of “technology-capability” and expand the scope of the study, the study reveals the operationalization path of the culture of cooperation to promote the enterprises’ access to more resources, the culture of innovation to drive the restructuring of resources, and the embedding of cultural capital into the dynamic capability. These findings are based on the theory of dynamic capability and the view of resource-based theory. The dualistic framework of “technology-capability” is bridged by this study, which also expands the scope of research on digital transformation. Simultaneously, this study enhances the content of resource-based theory and dynamic capability theory. While previous research has focused more on “hard” resources like technological capabilities, this paper adds cultural capital to the category of dynamic capability, reveals its catalytic role in resource acquisition and integration, and enhances the informal institutional foundation of dynamic capability. The traditional resource-based view of “hard” resources, like corporate culture, is more focused on the “hard” resources. By encouraging resource reconstruction, knowledge sharing, and learning innovation, this paper demonstrates how corporate culture can be converted into organizational competitive advantages, expanding the meaning of resource heterogeneity and imitability in the traditional view of resource base. The traditional view of resource-based theory pays insufficient attention to “soft resources” like corporate culture.

Future research suggests cross-country studies or extending the study’s timeframe to improve the external validity of the conclusions, but this study still has limitations despite drawing some significant conclusions. First, it only looks at Chinese A-share listed companies as a research sample from 2012 to 2021, making it difficult to represent the digitalization practices of a wide range of SMEs. Second, this study’s primary indicator of innovation capability is the quantity of patents that businesses have filed; this does not account for the multifaceted innovation performance of goods, procedures, or business models. Future research can present a more comprehensive innovation capability index system. Third, this study’s use of text mining to evaluate corporate culture has some subjectivity. To improve the robustness of the measurement variables, future research on corporate culture may incorporate qualitative interviews, in-depth semantic analysis, and other techniques. Fourth, case studies to examine how digitalization impacts innovation through the pathways of leadership, learning capability, and organizational resilience, as well as multi-level mediating and moderating variables to enhance the theoretical mechanism, can all be incorporated into future research to further expand the mechanism model between digital transformation and corporate innovation capability.

9. Implications

All parties should focus on digital transformation and industrial upgrading and pay more attention to the use of data elements and digital technology in production and life. The deepening application of digital technology drives the transformation and upgrading within each industry, but the empirical analysis revealed that the overall degree of digital transformation within each industry is uneven, and the degree of transformation is low.

To improve the ability of businesses to innovate and fully activate the vitality of the digital economy, the government should fortify top-level design to better support the process of digital transformation of the entire society. The government should create a system of diversified support policies first. The government can help state-owned businesses establish special funds to invest in “technology-culture” synergistic projects; for SMEs, the government should establish a third-party digital service platform to offer technical and consulting assistance for corporate innovation and digital transformation, while also increasing financial subsidies to ease financing challenges. Second, the government should encourage the development of digital platforms at the regional level. The government should remove data barriers, improve the ability of regions and businesses to collaborate, support industrial cluster innovation, and provide a single platform for the circulation of information based on the degree of digitization of various regions. Third, the government should highlight the role that informal systems have in governance. Fourth, the government can improve the development of innovative talent supply systems, encourage the synergistic evolution of organizational culture and innovative behaviors, and integrate corporate culture construction into industrial policy and innovation assessment systems. To infuse innovation with long-term power, the government should support university–business collaboration, establish talent subsidies, and stimulate talent mobility across regions.

Businesses should focus on developing data-driven open innovation ecosystems, extending resource boundaries through cross-organizational and cross-industry cooperation platforms around core data assets and value networks, and implementing a “dual-wheel drive” strategy of digital technology investment and cultural capital accumulation. Secondly, businesses should reshape their organizational culture and rebuild their assessment mechanisms. Businesses should also rebuild the evaluation system and change the company culture. To boost employees’ initiative and sense of identity in the face of technological change, cultural elements like learning, trust, and collaboration should be included in the employee performance evaluation system. At the same time, businesses should improve their collaboration with academic institutions and scientific research centers. To compensate for the lack of resources and expertise, small and medium-sized businesses in particular should take the initiative to integrate industrial innovation platforms and innovation alliances.

Lastly, from an industry standpoint, the advantages and challenges of digital transformation vary depending on the type of business. Rigid hierarchies, ineffective innovation incentives, strong organizational members’ resistance toward innovation, and a lack of transformation motivation are some of the issues facing SOEs. Therefore, to increase the overall capacity for innovation, state-owned enterprises should begin with internal change to encourage the flattening of the organizational structure. At the same time, they should begin with the top management team to foster a culture of innovation and collaboration, fortify the digital innovation-oriented performance appraisal system, and fully stimulate the staff’s potential for innovation. Although non-state-owned businesses are more focused on the market and are subject to more competition, they are also more proactive and adaptable when it comes to technological innovation and digital transformation. As a result, they ought to concentrate more on the competitive benefits of core digital technology, bolster the introduction and development of digital talent, and simultaneously strengthen the innovation and collaboration culture mechanism, create an open and effective internal environment, and raise the overall innovation effectiveness of businesses. Because they have a stronger digital basis and a more open and inclusive organizational culture, high-tech companies naturally have an innovation advantage over other business groups. Using digital platforms, such businesses can enhance information sharing both internally and externally. Second, they ought to realize the effective synergy of internal and external resources and fully unleash the potential of cultural capital in fostering innovation. The digital infrastructure, data capabilities, and organizational culture of traditional businesses, on the other hand, are clearly lacking, and they lack a strong feeling of innovation in general. Strengthening the digital foundation and encouraging the development of infrastructure should therefore be the top priorities. At the same time, businesses should collect cultural capital; improve their capacity for innovation and digital adaptability; and instill a spirit of cooperation, digital awareness, and open and inclusive cultural genes.