Abstract

Live-streaming e-commerce has attracted the attention of e-retailers and consumers in recent years. However, there is a lack of evidence in understanding the influence of atmospheric stimuli of live stream on consumer engagement. This paper seeks to examine the effect of festival cues in live-streaming studios on consumers’ intention to stay in the live-streaming context. Results of four laboratory experiments indicated that presenting festival cues enhanced consumers’ intention to stay. In the relationship between festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay, festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal played serial mediating roles. Product category moderated the effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay. For non-festival products, presenting festival cues led to a stronger intention to stay. The moderating role of involvement was significant in the relationship between festival cues and intention to stay. Regarding less involved consumers, presenting festival cues significantly enhanced their intention to stay. Our work contributes to the existing knowledge of e-commerce live-streaming, festivalscape, and festival shopping, and offers relevant managerial implications for live-streaming e-retailers.

1. Introduction

The live-streaming market size has grown rapidly in recent years. Purchasing from live-streaming broadcasting studios is a prevalent shopping experience [1]. Online shoppers watch live-streaming in which live streamers explain, present, and try products in broadcasting studios. By December 2023, the number of online live-streaming users in China had reached 816 million, an increase of 65.1 million compared to December 2022, accounting for 74.7% of the total number of internet users [2].

Live-streaming allows multiple consumers to interact at the same time, increasing their engagement. Live-streaming defies spatial restrictions, decreases information opacity, and provides an immersive experience [3,4,5,6]. Especially in various festivals, live-streaming marketers design their studios with the festive atmosphere in mind (i.e., Chinese New Year decorations), attracting festival shoppers, using festival promotions to sell their products, and aiming to achieve good retailing performance and strong festival sales during the festival selling periods [7,8,9]. Festivals are of vital importance for e-retailers. Many e-retailers employ live commerce to make huge profits during short festival periods. For example, the Chinese Singles’ Day festival atmosphere on online platforms increase consumers’ purchase intentions [7]. In China, Alibaba Singles’ Day (11 November) has become the most profitable online shopping festival (Singles’ Day in China (11 November) is the largest online shopping day in the world, bigger than Amazon’s Prime Day and Black Friday combined). The holiday atmosphere in a brand logo also influences consumers’ nostalgic preference [9]. In such, the success of festival consumption indicates the significance of festival atmosphere marketing.

However, it is surprising that the use of festival cues in live-streaming studios to influence consumers’ favorable responses is overlooked in the academic literature. In live-streaming studio, festival cues are cues (e.g., colors, decoration, symbols, or music) that are employed to create the festival consumption environment. In the present paper, we seek to investigate the impact of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay in the live-streaming context, explore the rationale behind the effect, and find the moderators in the relationship between festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay.

The current research offers several contributions. First, we contribute to the emerging research on the e-commerce live-streaming by investigating the consumers’ intention to stay on the environmental stimuli—festive atmospheric cues. Second, while prior literature has explored the effects of festivalscape on the consumers’ in-store attitude [10], our work suggests that in live-stream marketing, consumers’ involvement and product category can play an essential role on festivalscape perception and their intention to stay. Our research also offers implications for live-streaming marketers who strive to increase consumer engagement. Our findings suggest that the live-streaming e-retailers may want to create a festive atmosphere during festival periods to increase consumers’ intentions to stay.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. We first review the relevant literature on festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay to form the basis for our theoretical predictions. We then present the four studies to test the predicted effects and explore the underlying mechanism empirically. We conclude with theoretical and practical implications of our findings.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Festivals and Festival Cues

Festivals are important social occasions that are periodically recurrent, and members of a group, community, or country may participate through different approaches [9]. Festivals include traditional holidays (e.g., Christmas and the Spring Festival in China), appointed days (Alibaba Singles’ Day, 11 November), art festivals, music festivals, and brand anniversary celebrations. Socialization, escape, ambience, concessions, uniqueness, and activities are six festival attributes [11]. Festivals attract and retain international tourists [12], serve as the catalysts to local hotel industry [13], and play a relevant role in the tourism industry and regional retail businesses [10].

Cues that can convey a festival atmosphere include music and scent [14], TV advertisements [15], holiday symbols [9], events [16], festival products [17], and activities and concessions [11]. Lee et al. (2008) [10] summarized the following three categories of festival cues: (1) signs, symbols, and artifacts; (2) facilities and spaces; and (3) ambient conditions. In this paper, live-streaming studio festival cues are cues (e.g., colors, decoration, symbols, or music) that are employed to create the festival consumption environment.

2.2. Festival Cues and Consumers’ Intention to Stay

According to the S-O-R (stimulus–organism–response) paradigm, specific atmospheric cues influence consumers’ cognition and emotions, determining the consumers’ approach or avoidance response [18,19]. In the current research, we focus on consumers’ approach behavior in live-streaming studios and their intention to stay, which means the extent to which online shoppers are willing to remain in the live-streaming studios.

Consumers’ perception of the atmosphere influences time spent in the store [18] and revisit intentions [20]. Consistent results were found in the Web context [21,22,23] and in the mobile context [24]. Hoffman and Novak (1996) [25] concluded that if a consumer likes a site, their intention to stick is higher. Stickiness has often been considered an antecedent to loyalty, directly impacting a retailers’ bottom line [26], thus leading businesses to emphasize effective site design to increase positive return behavior by improving stickiness [27]. In the online store atmospherics’ context, design features have positively impacted on retail sales [28,29].

Here, in live-streaming broadcasting studios, during festival shopping periods, marketers carefully use festival cues during festival shopping periods to arrange studios and create a festival atmosphere. Festival cues that marketers employ can shape consumers’ cognition and approach behavior [10]. For example, Christmas music and Christmas scents lead to more favorable environment evaluations and stronger intentions to visit the store [14]. Online festival stimuli significantly enhance consumers’ purchase intentions and stickiness [7]. Even when consumers dislike the brand, they still may have a positive emotional response to the Christmas advertising of the brand [15] (Cartwright, McCormick, and Warnaby 2016).

Consistent with the previous research, we propose that during festival periods, the presence of festive cues could increase consumers’ intention to stay online in the live-streaming studios. Festivals are generally endowed with specific meanings [8] (Smith 1999). When live-streaming marketers employ unusual festive cues and offer a temporary, distinctive, festive atmosphere to consumers, consumers often enjoy a non-routine immersive experience [16] (Davis 2016). Thus, a consumer live-streaming studio relationship develops, and a meaningful interaction occurs. Therefore, consumers exposed to festival cues are more willing to stay at the live-streaming studios. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Compared with the absence of festival cues, the presence of festival cues enhances consumers’ intention to stay at live-streaming studios.

2.3. The Mediating Roles of Festivalscape Perceptions and Pleasure–Arousal

Marketers employ many festival atmosphere cues to create festivalscapes in live-streaming studios; these cues include typical festive music (“Jingle Bells” for Christmas), festival symbols (zongzi-the traditional food for the Chinese Dragon Boat festival; Chinese Spring Festival couplets), and slogans (brand anniversary celebrations). A festivalscape is not a natural environment but is rather designed by marketers who combine different tangible festival elements to create a festive atmosphere through which consumers can perceive the festival affectively and cognitively [30,31] (Kim and Moon 2009; Mason and Paggiaro 2012). In this paper, the festivalscape in live-streaming studios refers to the festival atmosphere perceived by consumers [10] (Lee et al. 2008). When marketers design a good festivalscape, consumers specifically notice the physical environment of the live-streaming studio, indulge in the hedonic experience, and enhance their satisfaction [31] (Mason and Paggiaro 2012). In the current research, we use the decorative atmosphere, adapted from Lee et al. (2008) and Mason and Paggiaro (2012) [10,31], to measure the live-streaming studio festivalscape.

According to the S-O-R paradigm, consumers’ emotions and behavioral intentions depend on their perceptions of environmental cues. S-O-R theory is derived from environmental psychology proposed by Mehrabian and Russell (1974) [19] to explore the factors affecting individual behavior, which suggests all aspects of the environment act as stimuli to jointly affect individuals’ internal state (O) and then drive their behavioral response (R). That is to say, the specific atmospheric stimuli, conceptualized as an influence that arouses an individual, does not directly affect individual behavior, but indirectly affects behavior through an internal process of intervention, such as perceptions, feelings, experience, and thoughts [32] (Bagozzi, 1986).

Bitner (1992) [33] found that physical elements in the environment influence consumers’ emotional responses and behavior. Eroglu, Machleit, and Davis (2001, 2003) [18,34] pointed out that atmospheric cues in an online store lead to high pleasure and arousal which in turn enhance approach behaviors. The findings of Park et al. (2019) [35] showed that servicescapes have a significant positive effect on positive emotional experiences (surprise, excitement, romance, peace, pride, and happiness) and behavioral intentions. The festivalscape is the stimulus in live-streaming studios that impacts consumer response. Lee et al. (2008) [10] found that the festivalscape influences consumers’ positive and negative emotions. Mason and Paggiaro (2012) [31] found that festivalscapes influence satisfaction and behavioral intention. Consistent with the literature, we propose that festivalscapes influence consumers’ emotional responses (e.g., pleasure and arousal). Pleasure and arousal are two emotional dimensions proposed by Mehrabian and Russell (1974) [19]; they are also two main emotions elicited by environment stimuli (Cheng, Wu, and Yen 2009) [36], and can adequately represent emotions evoked by atmospheric cues (Eroglu, Machleit, and Davis 2001) [18]. Pleasure refers to how people feel satisfied, happy, joyful, or good in a specific situation, whereas arousal refers to how people feel alert, active, stimulated, and excited (Cheng, Wu, and Yen 2009) [36]. Thus, we argue that festival cues in live-streaming studios create a festive atmospheric environment that elicits consumers’ festivalscape perception, which influences consumers’ emotions of pleasure and arousal, leading to increased intentions to stay. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2:

In the relationship between festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay, festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal play serial mediating roles.

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Product Category

The effect of festival cues on consumers’ intentions to stay may depend on the product category. In the current research, we divide product categories into festival products and non-festival products. These two kinds of products are tangible and can be sold in live-streaming broadcasting studios. A festival product, such as souvenirs, food, or drink, is designed and used for the specific festival, relates with the specific festival, and expresses a festival meaning (Mitchell et al. 1999) [37], whereas a non-festival product has nothing to do with the specific festival and can be used in daily life.

During festival periods, when live streamers sell products that have nothing to do with the festival, the effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay is similar to the effect in H1. That is, compared with live-streaming studios that lack festival cues, live-streaming broadcasting studios decorated with festival elements lead to more intense festival perceptions and pleasure and arousal, increasing consumers’ intention to stay. However, when live streamers sell festival products during the festival period, live-streaming studios with festival cues present might be perceived by consumers as more manipulative than festive. Consumers might perceive a manipulative intent, that is, they might infer that the marketers have employed unfair and inappropriate means to manipulate them to achieve persuasive effects (Campbell 1995) [38]. Inferences of manipulative intent significantly decrease marketers’ persuasion (Campbell 1995) [38]. Thus, the effect of the presence of festival cues in live-streaming studios will lower interest, and there may be no significant difference between the effects of the absence or presence of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay. Accordingly, we propose:

H3:

Product category moderates the effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay. Specifically, for non-festival products, the presence of festival cues significantly increases consumers’ intention to stay compared with the absence of festival cues, but for festival products, the effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay is not significant.

2.5. The Moderating Role of Involvement

Involvement is the extent of individual relevance (Ha and Lennon 2010) [39]. Consumers’ involvement is different in various situations. The patterns of information processing and behavior are different because of consumers’ diverse levels of involvement (Goh and Chi 2017; Wu, Wu, and Wang 2021) [40,41].

The elaborator likelihood model (ELM) suggests that the attitude of an individual is formed based on the theory of persuasive communication (Petty and Cacioppo, 1984) [42]. According to the ELM, the extent of elaboration received from persuasive communication ranges from no thoughts about the relevant information to complete elaboration of every argument (SanJosé-Cabezudo, Gutiérrez-Arranz, and Gutiérrez-Cillan, 2009) [43]. In a central route situation, consumers are prone to focus on the issue-related information (i.e., product information) for their decision making. On the other hand, consumers tend to use cues or heuristics in a peripheral route situation (i.e., festival cues) (Chen and Lee, 2008) [44]. The central route describes the process of attitude change when the level of message-relevant thinking is high, and the peripheral route describes attitude change when the level of such thinking is low (Voss, Spangenberg, and Grohmann, 2003) [45]. Consumer involvement can be regarded as an important factor of motivation to process information (Macinnis, Moorman, and Jaworski, 1991) [46], as highly involved individuals are more likely to evaluate the product through message-relevant thinking and form stronger attitudes towards it (Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Voss et al., 2003) [42,45]. Consumers who are less involved have weaker intentions and motivations to analyze information and are inclined to employ heuristic or peripheral cues (Wu, Han, and Chen 2024) [47].

As such, consumers with lower involvement are more likely to notice the festival cues and perceive the festivalscape. According to the SOR theory, festival cues are conceptualized as specific atmospheric stimuli that arouses an individual and then drive their behavioral response. The enhancement effect of the presence of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay is significant. Conversely, consumers who are more highly involved focus on key product information, for example, price, quality, color, style, or texture. Thus, the effect of the presence of festival cues will be attenuated. The difference between the effects of the presence or absence of festival cues will not be significant. Thus, we propose:

H4:

Involvement moderates the effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay. Specifically, for consumers with lower involvement, festival cues significantly enhance their intention to stay. However, for consumers who are more highly involved, the effect of festival cues on their intention to stay is not significant.

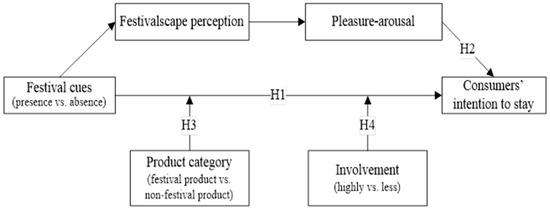

Based on these hypotheses, Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework of the relationships between variables.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

We test our hypotheses across four experiments given the unique strength of its internal validity (causality) due to its ability to link cause and effect through treatment manipulation, while controlling for the spurious effect of extraneous variable. We conducted four empirical studies to test all four hypotheses. In Study 1a and 1b, we used different festivals cues to test the main effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay (H1), and the mechanism through serial mediation (festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal; H2). Further, we tested the moderating role of product category in the relationship between festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay (H3) in Study 2, and the moderating effect of involvement (H4) in Study 3.

3. Study 1a

In Study 1a, we sought to test the main effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay (H1), and the mechanism behind the effect (the serial effects of festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal; H2).

3.1. Design and Procedure

We employed a one factor (festival cues: presence vs. absence) between-subjects design in Study 1a. One hundred and six undergraduate students (50 female) at the main University in Tianjin, China, participated in Study 1a. The festival in Study 1a was the Spring Festival. We designed two photos to represent two experimental conditions (see Appendix A Figure A1). In the treatment condition in which festival cues were present, we used Spring Festival elements such as Chinese characters (Happy Spring Festival), firecrackers, shoe-shaped gold ingots, and lanterns. In the treatment condition in which festival cues were absent, we did not add any festival elements to the photo. To keep the two photos equal, we employed the same background color and kept the pixel density of two photos consistent. We asked the participants to read the following scenario: “In your leisure time, you are browsing casually on your cellphone, and you happen to enter this live-streaming studio. Two live streamers are introducing an electronic toothbrush”.

3.2. Measures

In this study, we measured festival cues perception, festivalscape perception, pleasure–arousal, and consumers’ intention to stay. We used two questions to measure participants’ perception of festival cues (α = 0.92), and these two questions were the manipulation check questions: “This live-streaming studio employs some festival elements”, and “This live-streaming studio contains some festival cues”. The two items were measured by a seven-point Likert scale from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree. The measure of festivalscape perception (α = 0.74) was adopted from Kim and Moon’s study (2009) [30], using four seven-point Likert scale items: “The decoration of the live-streaming studio evokes the atmosphere of the Spring Festival”, “The live-streaming studio is decorated in the Spring Festival atmosphere”, “The decoration of live-streaming studio adds to the atmosphere of the Spring Festival”, “The atmosphere of the Spring Festival in live-streaming studio is salient” (1 = totally disagree; 7 = totally agree). We used six bipolar items, adopted from the study of Ha and Lennon (2010) [39], to measure pleasure and arousal. Three items in seven-point scales were used to measure pleasure (unhappy–happy, melancholic–contented, and annoyed–pleased (α = 0.91); and three items were used to measure arousal (unaroused–aroused, sluggish–frenzied, and sleepy–wide awake (α = 0.73)). The measure of consumers’ intention to stay (α = 0.94) was adopted from the research of Eroglu, Machleit, and Davis (2003) [34]; one example was “Once in the live-streaming studio, how much did you enjoy looking around? 1 = I did not enjoy looking around; 7 = I enjoyed looking around”.

3.3. Results

We first conducted the manipulation check analysis. A one-way ANOVA analysis showed that ratings of festival cues perception were significantly higher in the experimental condition when cues were present than absent (Mabsence = 3.49, Mpresence = 5.43, F (1, 104) = 81.30, p < 0.001). Thus, our manipulation of festival cues (presence vs. absence) was successful.

We also used a one-way ANOVA analysis to test the main effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay. Results indicated that the presence of festival cues lead to a stronger intention to stay. The ratings of consumers’ intention to stay were significantly higher when cues were present than absent (Mabsence = 4.25, Mpresence = 4.77, F (1, 104) = 5.07, p = 0.026). Thus, H1 was supported.

Further, we employed the PROCESS macro program in the statistical software SPSS 26.0 to conduct bias-corrected bootstrap analyses with 5000 iterations to examine the serial mediating effects (Hayes 2018) [48]. Serial mediation analysis was applied to test whether the association between festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay was mediated by festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal. When we added festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal into the model 6 of PROCESS Bootstrap, the serial mediating roles of festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal were significant (95% CI = −1.2065, −0.4426, excluding 0), indicating that the indirect effect was significant. This suggests that festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal play serial mediating role in the effect of festival cues on the intention to stay in the live-streaming studio. Hence, H2 was supported.

4. Study 1b

In Study 1a, we used the Spring Festival and designed the live-streaming studio in the Spring Festival atmosphere. In Study 1b, we sought to change the festival and to examine whether we could replicate the findings of Study 1a.

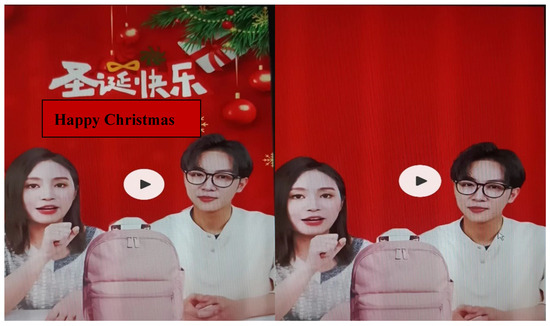

4.1. Design and Procedure

One hundred and ninety participants (ninety-eight female) were recruited from the WJX platform, a specialized data-collection platform in China, similar to Qualtrics and Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). We employed a one-factor between-subjects design, and the festival was Christmas. We used two video clips (see Appendix A Figure A2) to introduce the product and to manipulate festival cues. In the experimental condition, in which festival cues were present, we added Christmas cues, such as Chinese characters (Happy Christmas), a Christmas tree, and Christmas tree decorations. We also used the same background color in two video clips. We instructed the participants to read the following scenario, “In your leisure time, you are browsing casually on your cellphone, and you happen to enter this live-streaming studio. Two live streamers are introducing the backpack”.

4.2. Measures

The measures of the manipulation check question (α = 0.90), festivalscape perception (α = 0.76), pleasure (α = 0.90), arousal (α = 0.78), and consumers’ intention to stay (α = 0.89) were the same as those in Study 1a.

4.3. Results

We first employed a one-way ANOVA analysis to conduct the manipulation check. Results showed that participants rated their perception of festival cues higher in the presence of festival cues than in the absence of festival cues (Mabsence = 3.16, Mpresence = 5.46, F (1, 188) = 196.73, p < 0.001). Thus, our manipulation of festival cues (presence vs. absence) was successful.

The results of one-way ANOVA analysis showed that H1 was supported again. The effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay was significant, the ratings of consumers’ intention to stay were significantly higher when cues were present than absent (Mabsence = 4.53, Mpresence = 5.30, F (1, 188) = 13.11, p < 0.001). Further, the results of bootstrapping analysis showed that H2 was supported again, and the serial mediating effects of festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal were significant (95% CI = −1.5478, −0.8337).

5. Study 2

We sought to explore the moderating role of product category (festival product vs. non-festival product) in the relationship between festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay (H3) in Study 2.

5.1. Procedure and Measures

The festival in Study 2 was a Chinese festival, the Dragon Boat Festival. We selected zongzi as the festival product which is officially a Dragon Boat Festival food, and selected milk as the non-festival product. To determine whether these two products were representative, we conducted a pretest. Sixty-nine undergraduate students (38 female) at a major University in China participated in the pretest. We asked participants to rate the statements “The milk/zongzi”, “is unrelated to the festival/is related to the festival”, “had nothing to do with the festival/has something to do with the festival”, and we used a seven-point semantic differential scale (αmilk = 0.85 and αzongzi = 0.87). Results of a paired sample t-test showed that participants rated the zongzi higher than the milk (Mzongzi = 5.22, Mmilk = 3.54, t (68) = −10.22, p < 0.001). Thus, these two products could be used in the main study.

In Study 2, we employed a 2 (festival cues: absence vs. presence) × 2 (product category: festival product vs. non-festival product) between-subjects design. Two hundred and sixty-eight participants (138 female) were recruited from the Credemo platform, a specialized data-collection platform in China that offers data services to researchers across more than 3001a, 0 universities worldwide, similar to Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk).

In the experimental condition in which festival cues were present, we added Dragon Boat festival cues, for example, Chinese characters, the dragon boat, and the pattern of zongzi. In the experimental condition in which festival cues were absent, we did not add any festival cues. We used the same pink background across four experimental conditions and kept the pixel density of the four images equal (see Appendix A Figure A3). As in Study 1a and 1b, we told participants that, “The Dragon Boat festival is coming; in your leisure time, you are browsing casually on your cellphone, and you find two live streamers are introducing milk or zongzi in the studio”.

The measures of the manipulation check question (α = 0.90), festivalscape perception (α = 0.89), pleasure (α = 0.85), arousal (α = 0.86), and consumers’ intention to stay (α = 0.89) were the same as in the previous two studies. Further, we measured product category, and manipulative intent (α = 0.68) as an alternative explanation. We used one statement to determine how participants perceived the milk or zongzi, “The milk/zongzi is, 1 = not related to the festival, 7 = related to the festival”. We employed three items from a seven-point Likert scale adopted from Campbell’s (1995) [38] study to measure manipulative intent: “The live streamers try to sell the product in ways that I can accept”, “The live streamers try to be persuasive without being inappropriately manipulative”, and “The live streamers try to be persuasive without excessively controlling consumers” (1 = totally disagree; 7 = totally agree).

5.2. Results

Results of the one-way ANOVA analysis indicated that our manipulation of festival cues was successful (Mabsence = 4.42, Mpresence = 5.15, F (1, 266) = 10.32, p = 0.001), and our manipulation of the product category was successful (Mzongzi = 5.17, Mmilk = 2.60, F (1, 266) = 357.50, p < 0.001). The presence of festival cues led to a stronger intention to stay (Mabsence = 4.26, Mpresence = 4.60, F (1, 266) = 4.07, p = 0.045). H1 was supported again.

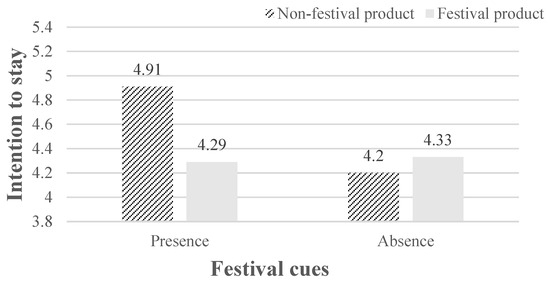

Two-way ANOVA results indicated that the main effect of product category was not significant (F (1, 264) = 2.16, p = 0.143), whereas the interaction effects of festival cues and product category on consumers’ intention to stay were significant (F (1, 264) = 5.39, p = 0.021). Simple effect analysis (see Figure 2) showed that for non-festival products, presenting festival cues led to a stronger intention to stay (Mabsence = 4.20, Mpresence = 4.91, F (1, 264) = 9.36, p = 0.002), but for festival products, there was no significant difference in the intention to stay between the presence of festival cues and their absence (Mabsence = 4.33, Mpresence = 4.29, F (1, 264) = 0.03, p = 0.869). H3 was supported.

Figure 2.

The interaction effects of festival cues and product category on consumers’ intention to stay.

Bootstrapping analysis results showed that H2 was supported again, and the serial mediating effects of festivalscape and pleasure–arousal were significant (95% CI = −0.2554, −0.0811).

We used manipulative intent as the mediating variable (alternative explanation), employed intention to stay as the dependent variable, and examined how festival cues and product category interactively influenced manipulative intent and intention to stay. An eight-model bootstrapping analysis showed that manipulative intent mediated the interaction effects of festival cues and product category on intention to stay, and the mediating effect was significant for non-festival products (95% CI = −0.3744, −0.0731). That is, consumers perceived a manipulative intent for festival products that were featuring festival cues in the live-steaming studio, and there was no significant difference between the effects of the absence or presence of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay for festival products. Although the mediated moderation effect of manipulative intent was significant, one-way ANOVA analysis results showed that the manipulative intent was not significantly different between the presence and absence of festival cues (Mabsence = 4.43, Mpresence = 4.68, F (1, 266) = 1.81, p = 0.18). Therefore, in the relationship between festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay, the mediating effect of manipulative intent was not significant.

6. Study 3

In Study 1a, Study 1b, and Study 2, we used different festivals that are typical holidays. In Study 3, we used festivals that were relevant to the brand: brand anniversary celebrations. In Study 3, we sought to test the moderating effect of involvement.

6.1. Procedures and Measures

Two hundred and forty-nine participants (127 female) from WJX platform took part in Study 3, which employed a 2 (festival cues: presence vs. absence) × 2 (involvement: high vs. low) between-subjects design. In the experimental condition in which festival cues were present, we presented the Chinese characters for “anniversary celebration”. In the experimental condition in which festival cues were absent, we did not present any cues. We also kept the background color and pixel density of the two photos equal (see Appendix A Figure A4). In the experimental condition of high involvement, we told the participants, “You have an urgent need to purchase a hand cream. Then, you enter a live-streaming studio in which two live streamers are introducing the hand cream”. In the treatment condition of low involvement, we told the participants, “You are browsing casually on your cell phones. Then, you enter a live-streaming studio in which two live streamers are introducing the hand cream”.

The measures of the manipulation check question (α = 0.71), festivalscape perception (α = 0.65), pleasure (α = 0.85), arousal (α = 0.75), manipulative intent (α = 0.84), and consumers’ intention to stay (α = 0.76) were the same as in Study 2. We used three items from a seven-point Likert scale to measure involvement (α = 0.76), as adopted from Wu, Wu, and Wang (2021) [41]. These items included “When you have an urgent need to purchase a hand cream/when you are browsing the live studios”, and “It will take a lot of time for me to process the information” (1 = totally disagree; 7 = totally agree).

6.2. Results

Results of the one-way ANOVA analysis indicated that our manipulation of festival cues was successful, and participants rated their perception of festival cues higher when festival cues were present and lower when they were absent (Mabsence = 4.06, Mpresence = 5.10, F (1, 247) = 27.28, p < 0.001). Our manipulation of the involvement was also successful. Participants scored involvement as higher in the high involvement condition than in the low (Mhighly involvement = 5.25, Mless involvement = 4.47, F (1, 247) = 21.75, p < 0.001).

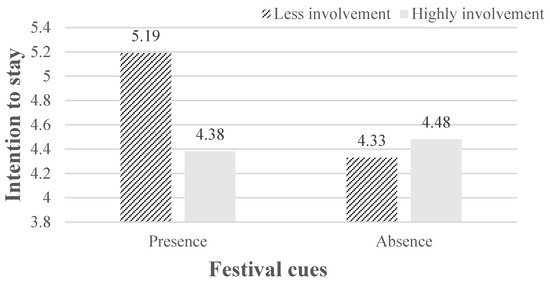

We conducted a two-way ANOVA analysis, and the results showed that the main effect of involvement was significant (F (1, 245) = 7.42, p = 0.007), and the interactions of the festival cues and involvement were significant (F (1, 245) = 15.20, p < 0.001). Results of simple effect analysis (see Figure 3) showed that for low involvement participants, the presence of festival cues led to a stronger intention to stay (Mabsence = 4.33, Mpresence = 5.19, F (1, 245) = 23.73, p < 0.001), but for highly involved participants, there was no significant difference in intention to stay between the presence and absence of festival cues (Mabsence = 4.48, Mpresence = 4.38, F (1, 245) = 0.29, p = 0.59). Thus, H4 was supported.

Figure 3.

The interaction effects of festival cues and involvement on consumers’ intention to stay.

Our bootstrapping analysis showed that the serial effects of festivalscape perception and pleasure–arousal were significant (95% CI = −0.2956, −0.1107). We also ruled out the alternative explanation of manipulative intent because the effect of festival cues on manipulative intent was not significant (Mabsence = 4.66, Mpresence = 4.72, F (1, 247) = 0.26, p = 0.61).

7. General Discussion

7.1. Conclusions

Live-streaming e-commerce has attracted the attention of e-retailers and consumers in recent years. This paper explored how festival cues (presence vs. absence) influenced consumers’ intention to stay online in live-streaming studios. The results of four laboratory experiments indicated that the presence of festival cues enhanced consumers’ intention to stay in live-streaming broadcasting studios (H1 was supported). Festival cues create a festive atmospheric environment that elicits people’s festivalscape perceptions, emotions of pleasure and arousal, and increased intentions to stay (H2 was supported). Applying the S-O-R paradigm (Eroglu et al., 2001; 2003) [18,34] allowed us to conclude that festival cues in this paper are the stimuli that induce consumers’ cognitions (festivalscape perceptions), emotions (pleasure and arousal), and approach behaviors (intention to stay).

In Study 2, we divided the product category into festival products and non-festival products and examined the moderating role of product category in the relationship between festival cues and consumers’ intention to stay. During the festival periods, e-retailers gather many products to sell and create a festivalscape to encourage online shoppers’ intention to purchase in their live-streaming studios (Chen and Li 2020) [7]. We found that selling festival products did not necessarily lead to positive outcomes. For non-festival products, presenting festival cues in the live-streaming studios enhanced consumers’ intention to stay (H3 was supported).

We conducted Study 3 to explore how involvement moderated the effect of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay. For less involved consumers, presenting festival cues increased their intention to stay; for more highly involved consumers, neither presenting nor withholding festival cues significantly influenced their intention to stay. The findings were consistent with the effect of involvement (Wu, Wu, and Wang 2021; H4 was supported) [41]. When people are highly involved, they rely on central routes to process information and evaluate vital attributes of products; when people’s involvement is lower, they process information depending on peripheral routes, and so heuristic cues are considered.

7.2. Theoretical Implications

Our current work contributes to existing knowledge in several dimensions. This paper supplements the emerging research on e-commerce live-streaming. The literature relating to the effects of live-streaming has focused on how live streamers influence consumers’ responses. For example, Zhang et al. (2022) [49] summarized live streamers’ eight characteristics and four roles. Zhao et al. (2021) [50] found that streamers’ social affordance, professionalism, and traits influenced their popularity. Guo, Zhang, and Wang (2022) [51] explored the effects of top streamers’ communication styles, competence, and attractiveness on their popularity and on consumers’ behavioral intentions (including watching intention and purchase intention). Meng and Lin (2023) [52] pointed out that the streamers’ characteristics and the perceived value of the platforms influenced consumers’ repurchase intentions. Yang et al. (2023) [6] examined how male and female streamers influence the selling of search and experience products. This paper supplements the literature on the effect of live-streaming by exploring the consumers’ intention to stay in the environmental stimuli, which are festive atmospheric cues.

Our research also enriches the literature on festivalscapes. The literature has examined various environmental cues pertaining to festivalscapes. For example, Lee et al. (2008) [10] proposed seven types of environmental cues that create a festivalscape. Mason and Paggiaro (2012) [31] used three indicators (comfort, fun, and food) to measure festivalscapes. In this paper, we only employed festival elements to decorate the background of live-streaming studios, and we found that decoration can enhance festivalscape perception.

The present paper extends the study of festival shopping. Chen and Li (2020) [7] pointed out that during festival periods, online shoppers’ participation, festival entertainment, and economic temptation all enhance purchase intention. Our work found that the festive environmental cues created by live-streaming studios influence the intentions of consumers to stay in the live-streaming context and provide new insights for research into festival shopping.

This paper also tested the explanation power of the S-O-R paradigm. The S-O-R paradigm has been employed to analyze how different stimuli presented by online stores influence consumers’ responses (Chen and Li 2020; Eroglu, Machleit, and Davis 2001) [7,18]. Consistent with the literature, we found this paradigm applied to our research, and the stimuli (festival cues) elicited cognition (festivalscape perceptions), emotions (pleasure and arousal), and approach behaviors (consumers’ intention to stay).

7.3. Managerial Implications

E-commerce live-streaming is a prevalent method for selling various products. Our study tested the effects of festival cues in live-streaming on consumers’ intention to stay, and our findings have some practical implications for e-commerce live-streaming marketers.

During festival periods, live-streaming e-retailers provide various marketing stimuli (free freight, discounts, coupons, and so on) to encourage online shoppers to participate and purchase. During festival periods, creating a festive atmosphere is important. The layout and decoration of live-streaming studios that are designed in a festive atmosphere can increase consumers’ festivalscape perceptions, elicit consumers’ pleasure and arousal, and enhance consumers’ intentions to stay.

The current research also offers relevant insights into how to sell products effectively in live-streaming studios during festival periods. Because the effect of presenting festival cues will attenuate for festival products and highly involved consumers, live-streaming e-retailers should carefully select the products they sell in the live-streaming studios and consider different target consumers.

7.4. Limitations and Future Research Avenues

The present paper has explored how festival cues influence consumers’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses. Festivals in this paper are mainly holidays, such as the Spring Festival, Christmas, and the Dragon Boat Festival. Further study can use more festivals, such as art festivals and music festivals. In the present paper, we only employed typical festival elements in the background of live-streaming studios to manipulate the presence of festival cues. However, festival cues can be presented via different methods. In future research, using various methods to present festival cues and manipulate consumers would be more desirable. For example, live streamers can put on festive costumes, or live streamers can play festive music. Live-streaming e-retailers can also use AI to create personalized festival cues, such as crafting custom birthday messages, cards, and decorations for birthday celebrations.

Furthermore, the collected data were from Chinese participants, and the effects of different national contexts were not considered. Although we found that both Spring Festival cues and Christmas festival cues had a positive effect on Chinese consumers’ responses (study 1), future research is also required to investigate the impact of festival cues (e.g., Chinese festival) in other cultural contexts (e.g., US participants).

Finally, we did not consider the promotion of the festival products in live-streaming studios. In fact, during festival periods, festival products are sold at relatively reasonable prices (Lee, Lee, and Choi 2011) [17], and many e-retailers will take advantage of the festival shopping to earn profits. Future research can further explore the interaction effect of festival cues and promotions (price discounts, coupons, etc.) on consumers’ intention to stay.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W. and H.J.; methodology, R.W. and H.J.; software, R.W.; validation, R.W., and H.J.; formal analysis, R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W.; writing—review and editing, H.J.; funding acquisition, R.W. and H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Fund of China [Grant No. 22FGLB099], and the Humanities and Social Sciences Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China [Grant No. 21YJC630048], and the Jilin Scientific and Technological Development Program [Grant No. 20210601083FG].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it did not involve any interventions or procedures that required ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Images in Study 1a.

Figure A2.

Video clips in Study 1b.

Figure A3.

Images in Study 2.

Figure A4.

Images in Study 3.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Direct and indirect effects of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay in Study 1a.

Table A1.

Direct and indirect effects of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay in Study 1a.

| Outcome | β | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect Festival cues-Consumers’ intention to stay | -.5387 | .2119 | -.9581 | -.1174 |

| Indirect effect Festival cues-Festivalscape perception-Consumers’ intention to stay | .4038 | .1971 | .0736 | .8606 |

| Festival cues-Pleasure arousal-Consumers’ intention to stay | .3564 | .1580 | .0743 | .7044 |

| Festival cues-Festivalscape perception-Pleasure arousal-Consumers’ intention to stay | -.7458 | .1887 | -1.2065 | -.4426 |

Table A2.

Direct and indirect effects of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay in Study 1b.

Table A2.

Direct and indirect effects of festival cues on consumers’ intention to stay in Study 1b.

| Outcome | β | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect Festival cues-Consumers’ intention to stay | -.4341 | .1842 | -.7975 | -.0707 |

| Indirect effect Festival cues-Festivalscape perception-Consumers’ intention to stay | .4990 | .1669 | .2044 | .8561 |

| Festival cues-Pleasure arousal-Consumers’ intention to stay | .3091 | .1413 | .0465 | .5930 |

| Festival cues-Festivalscape perception-Pleasure arousal-Consumers’ intention to stay | -1.1442 | .1783 | -1.5478 | -.8337 |

References

- Cunningham, S.; Craig, D.; Lv, J. China’s livestreaming industry: Platforms, politics, and precarity. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2019, 22, 719–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNNIC (China Internet Network Information Centre). The 53rd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development; CNNIC: Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 48–49. Available online: https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202405/P020240509518443205347.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Ang, T.; Wei, S.; Anaza, N.A. Livestreaming vs. pre-recorded: How social viewing strategies impact consumers’ viewing experiences and behavioral intentions. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 2075–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, P.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Tan, W.H.; Ooi, K.B.; Aw, C.X.; Metri, B.; Woodside, A.G. Why do consumers buy impulsively during live streaming? A deep learning-based dual-stage SEM-ANN analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkitrungrueng, A.; Assarut, N. The role of live streaming in building consumer trust and engagement with social commerce sellers. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Li, S. Impact of streamers? Characteristics on sales performance of search and experience products: Evidence from Douyin. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, X. Effects of Singles’ Day atmosphere stimuli and Confucian values on consumer purchase intention. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 1387–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.F. Urban versus suburban consumers: A contrast in holiday shopping purchase intentions and outshopping behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, R. It reminds me of my happy childhood: The influence of a brand logo’s holiday atmosphere on merchandise-related nostalgic preference. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, C.K.; Lee, S.K.; Babin, B.J. Festivalscapes and patrons’ emotions, satisfaction, and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanford, S.; Jung, S. Festival attributes and perceptions: A meta-analysis of relationships with satisfaction and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Mei, W.S.; Tse, T.S.M. Are short duration cultural festivals tourist attractions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Fetter, E. Can a festival be too successful? A review of Spoleto, USA. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2006, 18, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B.; Sprott, D.E. It’s beginning to smell (and sound) a lot like Christmas: The interactive effects of ambient scent and music in a retail setting. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, J.; McCormick, H.; Warnaby, G. Consumers’ emotional responses to the Christmas TV advertising of four retail brands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A. Experiential places or places of experience? place identity and place attachment as mechanisms for creating festival environment. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-S.; Lee, C.-K.; Choi, Y. Examining the role of emotional and functional values in festival evaluation. J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L.M. Atmospheric qualities of online retailing: A conceptual model and implications. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 54, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Varshneya, G.; Das, G. Experiential value: Multi-item scale development and validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Lassar, W.M.; Butaney, G.T. The mediating impact of stickiness and loyalty on word-of-mouth promotion of retail websites. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 1828–1849. [Google Scholar]

- Ettis, S.A. Examining the relationships between online store atmospheric color, flow experience and consumer behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sina, A.S.; Wu, J. Effects of 3D vs. 2D interfaces and product-coordination methods. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 855–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, H.-Y. Consumer need for mobile app atmospherics and its relationships to shopper responses. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P. Marketing in hypermedia computer-mediated environments: Conceptual foundations. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Baek, T.H.; Kim, Y.-K.; Yoo, K. Factors affecting stickiness and word of mouth in mobile applications. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2016, 10, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Hu, P.J.H.; Sheng, O.R.L.; Lee, J. Is stickiness profitable for electronic retailers? Commun. ACM 2010, 53, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, A.V.; Siekpe, J.S. The effect of web interface features on consumer online purchase intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reydet, S.; Carasana, L. The effect of digital design in retail banking on customers’ commitment and loyalty: The mediating role of positive affect. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 37, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Moon, Y.J. Customers’ cognitive, emotional, and actionable response to the servicescape: A test of the moderating effect of the restaurant type. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Paggiaro, A. Investigating the role of festivalscape in culinary tourism: The case of food and wine events. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P. Principles of Marketing Management; Science Research Associates: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, S.A.; Machleit, K.A.; Davis, L.M. Empirical testing of a model of online store atmospherics and shopper responses. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Back, R.M.; Bufquin, D.; Shapoval, V. Servicescape, positive affect, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: The moderating role of familiarity. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 78, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.F.; Wu, C.S.; Yen, D.C. The effect of online store atmosphere on consumer’s emotional responses—An experimental study of music and color. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2009, 28, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W.; Davies, F.; Moutinho, L.; Vassos, V. Using neural networks to understand service risk in the holiday product. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 46, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.C. When attention-getting advertising tactics elicit consumer inferences of manipulative intent: The importance of balancing benefits and investments. J. Consum. Psychol. 1995, 4, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.; Lennon, S.J. Online visual merchandising (VMD) cues and consumer pleasure and arousal: Purchasing versus browsing situation. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, D.; Chi, J. Central or peripheral? Information elaboration cues on childhood vaccination in an online parenting forum. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.L. Why is a picture worth a thousand word? Pictures as information in perceived helpfulness of online reviews. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. Source factors and the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Adv. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 668–672. [Google Scholar]

- SanJosé-Cabezudo, R.; Gutiérrez-Arranz, A.M.; Gutiérrez-Cillán, J. The combined influence of central and peripheral routes in the online persuasion process. Cyber Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H.; Lee, K.P. The role of personality traits and perceived value in persuasion: An elaboration likelihood model perspective on online shopping. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2008, 36, 1379–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, K.E.; Spangenberg, E.R.; Grohmann, B. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of consumer attitude. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macinnis, D.J.; Moorman, C.; Jaworski, B.J. Enhancing and measuring consumers’ motivation, opportunity, and ability to process brand information from advertisements. J. Mark. 1991, 55, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Han, Y.; Chen, S. Awe or excitement? the interaction effects of image emotion and scenic spot type on the perception of helpfulness. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781609182304. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, C.; Li, X.; Ren, A. Characteristics and roles of streamers in e-commerce live streaming. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 1001–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Hu, Y.; Hong, Y.; Westland, J.C. Understanding characteristics of popular streamers on live streaming platforms: Evidence from Twitch.tv. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2021, 22, 1076–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wang, C. Way to success: Understanding top streamer’s popularity and influence from the perspective of source characteristics. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.Y.; Lin, M.Y. The driving factors analysis of live streamers’ characteristics and perceived value for consumer repurchase intention on live streaming platforms. J. Organ. End User Comput. 2023, 35, 323187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).