Abstract

This research explores how the partitioned pricing strategy of premium subscriptions affects user willingness to purchase with two studies. Study 1 finds that all-inclusive pricing is more effective than traditional partitioned pricing (i.e., partitioned pricing in Single) and the two new formats of partitioned pricing (i.e., partitioned pricing in Combination and partitioned pricing in Blind Box) in terms of increasing user willingness to purchase due to the induced higher perceived value and perceived price fairness. Study 2 further finds that partitioned pricing in Combination or partitioned pricing in Blind Box (vs. partitioned pricing in Single) can affect perceived value positively via perceived playfulness and negatively via user-perceived price complexity simultaneously. These indirect effects hold across hedonic and utilitarian digital content products. These findings contribute to the literature on the pricing strategies of subscription-based digital content platforms. This research also provides suggestions for digital content platforms to adopt that will help them design their partitioned pricing strategies effectively.

1. Introduction

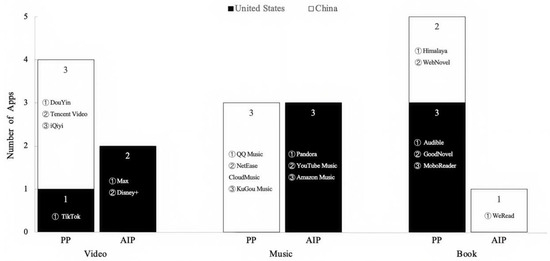

Premium subscription businesses, which charge users for the periodic use or access to digital content products (e.g., online videos, digital music, and e-books), is widely observed on digital content platforms [1,2,3,4]. Two prevalent pricing strategies of premium subscription plans on digital content platforms are all-inclusive pricing (hereinafter “AIP”) and partitioned pricing (hereinafter “PP”) [5]. The AIP strategy allows a platform to charge a fixed price (e.g., a premium membership fee) for access to all of its digital content products, whereas the PP strategy divides the price into a fixed price for some paid content products and an additional price for certain other content products (e.g., a membership fee plus surcharges). Although both pricing strategies have been adopted by some bestselling digital content applications (apps) on the Apple store (see Appendix A, Figure A1), the respective profitability elements of the PP or AIP strategies makes choosing a strategy a difficult decision for platforms. For example, in 2022, iQIYI, a digital content platform using the PP strategy (e.g., USD 5.99 per month plus usage-based price), turned a profit for the first time after ten years of struggling for profit, whereas the annual net income of Netflix, another digital content creation and distribution platform that uses the AIP strategy (e.g., USD 15.49 per month for the standard plan), fell for the first time after growing for a decade. Thus, it is important for platforms to understand the relative effectiveness of PP versus AIP when deciding on the pricing strategy of their subscription plans, given the business features of digital content products.

Extant research has not concluded that either PP or AIP is more effective in generating favorable user responses and profits for digital content platforms. Traditional studies following prospect theory, which argues that multiple losses are more punishing than a single loss of the same amount, suggest that users prefer AIP due to the lower perceived cost or the lack of additional costs to acquire the same products [5,6]. Yet, despite this cost-saving effect of AIP, one-third of users of digital book platforms still choose PP, which may reduce their welfare while increasing the platform’s profits [3]. Regarding this inconsistency, few studies compare the underlying influencing mechanisms of AIP and PP on user reaction, although some studies have revealed that either strategy can influence user reaction by altering users’ perception of value and price fairness [7,8]. This lack of comparison limits our understanding of the effectiveness of these two pricing strategies, especially for the subscription plans of digital content platforms.

The literature on PP pays relatively little attention to the unique characteristics of digital content products for subscription-based pricing on digital content platforms. As shown in Table 1, most of the existing studies examine the PP of traditional goods or services, except for a few recent studies that began to examine the subscription-based pricing strategies of digital content products. This new exploration is worthwhile because the uniqueness of digital content products (e.g., purchased and used online, zero replication cost) may alter the pricing strategy preference of both platforms and users [9]. For example, a recent report suggests that the traditional cost-based pricing strategy may be invalid in terms of the development of digital content platforms due to the cost structure of digital content products, thus calling for the exploration of more innovative value-based pricing strategies for digital content platforms [10]. Moreover, a large volume of digital content products can be stored, bundled, and delivered to users without physical inventory limitations [1]. However, the effectiveness of various feasible subscription-based PP strategies based on the flexible delivery of digital content products is under-researched. This lack of exploration restrains digital content platforms from innovating their pricing strategies to maximize subscription revenues.

Table 1.

Selected studies on AIP and PP.

To address the above gaps, this research aims to explore how the PP strategy of subscription plans on digital content platforms affects user willingness to purchase (hereinafter “WTP”). Specifically, this research addresses the two following questions with two studies: (1) Is PP as effective as AIP in driving user WTP on digital content platforms? (2) If not, how can PP be better utilized to increase user WTP? Study 1 finds that all three PP strategies (i.e., PP in Single, PP in Combination, and PP in Blind Box) are less effective than AIP in promoting WTP due to the lower user-perceived value and perceived price fairness. However, the empirical results also reveal that neither PP in Combination nor PP in Blind Box shows a different effect from PP in Single in terms of perceived value, perceived price fairness, and WTP, though these two innovative PP strategies incorporate the bundling idea of AIP. Regarding these nonsignificant effects, Study 2 further examines the mechanisms of these three PP strategies in terms of user-perceived value. It finds that either PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box, relative to PP in Single, can increase user-perceived value through increased user-perceived playfulness while decreasing the perceived value through increased perceived price complexity. This offsetting effect partially accounts for the zero total effect of PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) on perceived value.

The rest of this article is structured as follows. The next section presents the theoretical foundation. Section 3 overviews the conceptual model and two studies. Section 4 and Section 5 report Study 1 and Study 2, separately. Finally, this article discusses the implications of the findings and concludes with a discussion of limitations and future research directions.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

2.1. Literature Review of Partitioned Pricing

PP refers to the strategy of dividing price into a base price and one or more mandatory surcharges [11]. Previous research indicates that the surcharge of partitioned pricing can affect users’ evaluation of value or price fairness. For example, the presentation format of price (dollars vs. percentage), surcharge types (sales tax vs. handling fee), amount of surcharge (small vs. large), and the level of surcharge (low vs. high) can alter users’ responses [7,8,11,12,13]. Moreover, surcharge benefits, fairness of the surcharge, and significance of the surcharge also influence the effectiveness of the PP strategy [8,14,15].

Most previous studies compare the effectiveness of PP and AIP in traditional contexts (e.g., online shopping, car rental, airlines). These studies have shown that PP generates higher purchase intentions than AIP due to the relatively low surcharge of PP, increased informational effect of price, and independent self-construal of users [8,15,16,17].

Recent work on PP has started to explore the optimal subscription-based PP strategy for digital content products. For example, Zhang et al. provide evidence that, on digital book platforms, users may overpay by choosing pay-per-chapter to prevent excessive consumption compared with monthly subscriptions [3]. Users with higher usage rates of digital goods prefer a subscription set that includes all items, while users with lower usage rates prefer to rent a single item [1].

Overall, the existing literature provides evidence to improve the effectiveness of the PP strategy. However, few studies compare the effectiveness of innovative PP and AIP and their influencing mechanisms on digital content platforms.

2.2. Digital Content Platform

A digital content platform is a digital platform for users to browse, use, and purchase digital content products such as online videos, digital music, and e-books [18,19]. Digital content platforms connect content users with content providers [20,21]. Users pay a subscription fee to access digital content products and services on platforms [22]. Content providers produce and sell various digital content products through the platforms. Digital content platforms provide users with access to free and paid digital content products and utilize personalized recommendations to increase user WTP and subscription revenues. This research focuses on how digital content platforms earn revenues from user subscriptions to paid content products (i.e., premium subscription business), though platforms can also earn revenues from advertisers who promote their products and services on platforms.

The quality of a digital content platform is a key determinant of users’ subscription. It is manifested in its content benefits and network benefits [23]. Content benefits refer to the digital content product-related benefits users enjoy from using the platform, such as the number of exclusive content and the speed of content releases. Network benefits refer to the benefits users enjoy from the installed user base or content provider base. It can be indirectly reflected by the view counts, the number of user comments, and the number of copyrighted resources.

The content products on digital content platforms can be hedonic or utilitarian. Hedonic digital content products, such as TV dramas, movies, shows, and animations, provide users with more experiential benefits (e.g., fun, pleasure, enjoyment, excitement, and fantasy). Utilitarian digital content products provide users with more instrumental benefits (e.g., functionality, practicality, and usefulness) [24]. Examples of utilitarian digital content products include skill-training content, online courses, and book reviews. This classification of content products (i.e., product type) affects users’ information-processing mode and decision-making focus [25]. In general, users of hedonic products are more pleasure-oriented and make purchase decisions based on their feelings, whereas users of utilitarian products are more goal-oriented and make purchase decisions for the purpose of filling basic needs or accomplishing tasks [24].

2.3. Subscription-Based Pricing Strategy

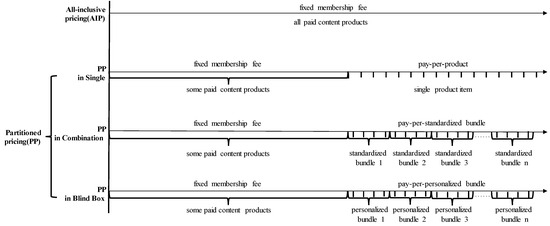

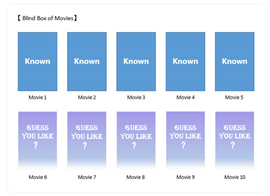

The pricing of premium subscription plans influences platform profit [26]. A subscription-based pricing strategy involves the design of a fixed membership fee and other surcharges [22,27]. The fixed membership fee is often charged because it is necessary for platforms to gain subscribers. Other surcharges for certain selective products or services, which could be requested or not, may strongly affect users’ usage [28]. According to the presentation format of surcharges (i.e., no surcharge, an individual surcharge, or a combined surcharge is presented), this research focuses on four subscription-based pricing strategies, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An illustration of AIP and PP for subscription plans.

AIP is a pricing strategy in which a firm charges a single, all-inclusive price (e.g., a fixed membership fee) that combines all products, with no additional surcharges [11]. For example, Netflix charges users USD 15.49 per month for the standard plan to access all paid movies, TV shows, and mobile games. Essentially, AIP involves bundling pricing that integrates and sells two or more separate items at a single price [29]. In the AIP context, users’ perception of cost is relatively lower according to prospect theory [6].

PP is a pricing strategy that involves charging users a base price (the larger amount) and a surcharge (the smaller amount) [11]. PP in Single indicates that the surcharge is paid-per-product. For example, iQIYI charges users both a fixed membership fee (e.g., USD 5.99 per month for the standard subscription plan) to access some paid videos and a surcharge for each of the certain videos (e.g., exclusive TV series, newly released copyrighted movies) which users request to access. The PP strategy is regarded as an effective approach to increasing platforms’ profits [3], though the multiple price components may be perceived as unfair [12].

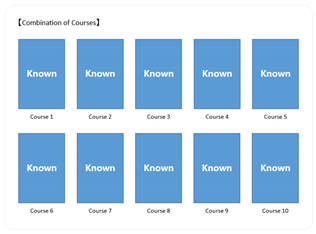

As depicted in Figure 1, PP in Combination requires users to pay for a fixed membership fee plus a pay-per-standardized bundle (i.e., a package of content products known before purchase) price. It is an innovative PP strategy that is implemented based on the flexibility of digital content products to be presented as product bundles. PP in Combination is different from PP in Single because it borrows the idea of bundling pricing, which is a salient characteristic of AIP [8].

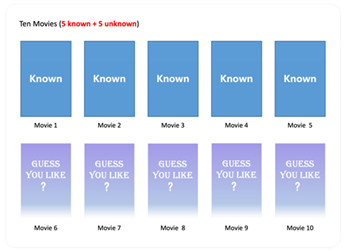

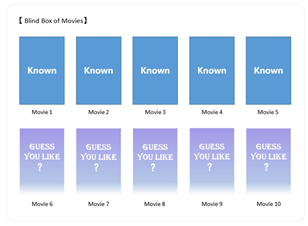

Another innovative PP strategy, PP in Blind Box, draws on the idea of probabilistic goods. It requires users to pay for a fixed membership fee plus a pay-per-personalized bundle (i.e., a package with some content products unknown before purchase) price. PP in Blind Box is a variant of PP in Combination, in that part of a standardized bundle is personalized based on the user’s preferences or usage records [22,30]. Users are not fully aware of all the exact content products of a bundle until they make a purchase, thus making it probabilistic goods [31]. This probabilistic selling technique adds uncertainty to product assignments, thus bringing users a pleasant experience, playfulness, and enjoyment.

2.4. Perceived Value and Perceived Price Fairness

Perceived value is a user’s overall assessment of the utility of a product based on the perception of what is received (i.e., benefits) and what is given (i.e., sacrifices) [32]. Benefits refer to what users are seeking, expecting, or experiencing when they purchase or consume a product. For example, when users purchase a subscription plan for digital content products, they receive quality benefits and taste benefits for functional value (e.g., usefulness, reliability) or emotional value (e.g., playfulness, novelty) [33,34]. Sacrifices involve users’ perceptions of monetary sacrifices (e.g., price) or non-monetary sacrifices (e.g., time, energy, effort) to obtain or use a product [35]. The perceived value of a subscription plan can be boosted by either increasing the benefits or reducing the sacrifices associated with the purchase or use of the subscription plan [36,37,38]. Accordingly, this study defines the perceived value of a subscription plan on digital content platforms as an assessment of the perceived net benefits based on the comparison of the benefits received in acquiring digital content products with the payment under a specific pricing strategy of the subscription plan.

Perceived price fairness can be defined as the judgment of whether a price and/or the process of reaching this price in an exchange are reasonable, acceptable, or just [39]. The cognitive aspect of this definition indicates that the perception of price fairness is induced when users compare the outcome (e.g., input and output ratio) with other comparative outcomes [40]. In the PP context, the level, optionality, and disclosure timing of surcharges influence users’ perception of the price fairness of a subscription plan, which in turn impacts users’ purchase or recommendation intentions regarding the plan [8,38].

3. Research Model and Overview of Studies

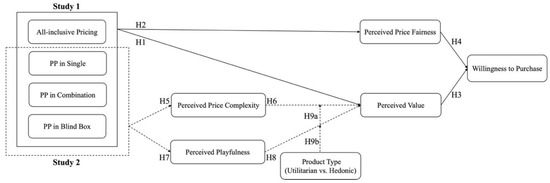

Building on Xia et al. [40].’s (2004) framework of examining pricing effects on user reactions, this research includes both perceived value and perceived price fairness as the mediators to compare the influencing mechanisms of pricing strategies on WTP in terms of subscription plans. Perceived value is included because the price under a specific pricing strategy of a premium subscription, as well as the benefits associated with that price, influences users’ value perception [33]. Moreover, perceived price fairness is a proper mediator because it influences user WTP for premium subscription plans and appears to be the key to determining whether or not PP is more profitable than AIP [8,41]. As shown in Figure 2, Study 1 compares the effectiveness of three PP strategies to that of AIP in increasing user WTP, with perceived value and perceived price fairness acting as the mediators.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model.

Given the empirical results of Study 1, Study 2 further explores the influencing mechanisms of three PP strategies, as shown in Figure 2. It examines the mediating roles of perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness, drawing on the idea that users’ value perception of pricing is influenced by their perceived benefits and perceived sacrifices [40]. Study 2 also examines whether product type moderates the effects of user-perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness on user-perceived value.

4. Study 1: The Effectiveness of PP Versus AIP

The goal of Study 1 is to compare the effectiveness of PP with that of AIP in increasing user WTP on digital content platforms. It examines how pricing strategy affects user WTP for subscription plans through perceived value and perceived price fairness.

4.1. Hypotheses

The user-perceived value of a subscription plan under AIP is relatively higher because the perceived monetary sacrifice in the condition of AIP is lower than that in the condition of PP, assuming a given perceived benefit. Prospect theory states that multiple losses are generally more painful than a single loss of equal monetary value [6]. Under PP, users experience multiple losses when they purchase several paid content products in addition to a subscription plan, whereas AIP leads users to perceive a single loss through integrating multiple payments into a single payment of the subscription plan. Thus, users may feel that they pay less under AIP than under PP even though the sum of their actual payments under different subscription plans may be the same. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H1.

User-perceived value is higher in the AIP condition than in the (a) PP in Single, (b) PP in Combination, and (c) PP in Blind Box conditions.

The user-perceived price fairness of subscription plans under AIP is relatively higher than that under PP because users may seek reasonable explanations for the additional payment. The subscription business of digital content platforms often confronts the challenges of price fairness, especially when similar content products were previously free to access online [41]. Once having purchased a subscription plan for the paid content (e.g., a fixed membership fee), users are more likely to feel it unreasonable if they are asked for additional payment for certain paid content (e.g., surcharges for each product) [8]. For example, under PP (vs. AIP), users may believe that they are nickel-and-dimed by the platforms with exclusive content resources and thus the pricing is unfair [40]. Moreover, the reduced frequency of reasonableness evaluation of payment under AIP can lower the possibility of detecting an unfair price [8]. Thus, it is less possible for users to perceive price fairness under PP (vs. AIP). In addition, although the perceived fairness of the additional payment depends on the level of surcharges, users may regard this payment in a subscription plan as unreasonable even when the actual total of surcharges is small [7,8]. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H2.

User-perceived price fairness is higher in the AIP condition than in the (a) PP in the Single, (b) Combination, and (c) Blind Box condition, respectively.

WTP refers to the likelihood that a user intends to purchase a product [36]. User-perceived value and perceived price fairness are critical determinants of users’ decision to purchase [37,42]. For the products with a higher perceived value that satisfies users’ needs and expectations, users show a stronger willingness to purchase [32]. For example, the subscription plans of online music platforms (vs. traditional music stores) which bring more perceived benefits (e.g., usefulness and playfulness) or reduced perceived sacrifices (e.g., price) can encourage users to subscribe online [38].

The user-perceived fairness of a price can positively influence WTP for subscription plans [8]. Once users perceive the unfairness of a price, they will generate negative emotions and resistance, thus decreasing their WTP for that subscription plan [43]. With higher user-perceived unfairness, users experience upset, regret, or disappointment [44]. This negative emotion can provoke users to reduce their payments or even leave the subscription plan [40]. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H3.

User-perceived value is positively related to user WTP.

H4.

User-perceived price fairness is positively related to user WTP.

4.2. Experiment 1

4.2.1. Experimental Design and Procedure

Given that the quality of a digital content platform is a key factor influencing user WTP of subscription plans, Study 1 adopted two experiments to test the hypotheses sequentially. Experiment 1 first examined the effect of PP in Single, the most representative PP strategy, with the consideration of platform quality. Then, experiment 2 compared the effect of each PP strategy with that of AIP. Thus, Study 1 used a 2 (pricing strategy: AIP vs. PP in Single) × 2 (platform quality: low quality vs. high quality) between-subject design. A total of 538 subjects (Mage = 34.3, 67.8% female; see Appendix B, Table A1 for demographic details) recruited from Credamo (a leading online marketing research platform in China) were randomly assigned to one of the four scenarios.

The pricing strategy was manipulated by providing subjects with two different premium subscription plans on a fictitious digital video platform. As shown in Appendix C (Table A2), in the AIP strategy condition, subjects could access all paid videos during the subscription period with a single payment for the membership fee. In the PP in Single strategy condition, subjects paid a membership fee to access some paid videos and needed to pay extra fees to access certain selective videos during the subscription period.

The platform quality was manipulated by providing subjects with a description of four quality dimensions, namely the number of copyrighted resources, the high-quality exclusive content, the user base, and the launching of new content products. These four dimensions were recognized as the most important among the ten determinants of platform quality in a pre-test (see Appendix D, Table A3). A high-quality video platform in scenarios was characterized with rich copyrighted resources, a large number of viewers, high-scoring exclusive content, and a quick content release strategy.

Subjects assumed that they would be purchasing a premium subscription plan to access paid videos on the video platform. They first read the given scenario description and then completed the manipulation check. Next, subjects reported their WTP, perceived value, and perceived price fairness.

4.2.2. Measures

Previously validated items were adapted to measure perceived value, perceived price fairness, and WTP with seven-point Likert scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Perceived value was measured with four items adapted from Sirdeshmukh et al. [45]. (α = 0.966). Perceived price fairness was measured with three items adapted from Kukar-Kinney et al. [46]. (α = 0.945). WTP was measured with three items adapted from Dodds et al. [36]. (α = 0.960). All measures are reported in Appendix E (Table A4).

4.2.3. Manipulation and Realism Checks

Pricing strategy. After reading the given scenario, subjects were asked to pick the subscription plan in the scenario (i.e., “membership fee-only” and “membership fee plus pay-per-video”). All subjects correctly answered this question. Thus, the manipulation of the pricing strategy was successful.

Platform quality. Subjects were asked to evaluate the platform quality in scenarios on a seven-point Likert scale: “The overall quality of this video platform is high”. The results of an independent samples t test showed that subjects’ perceived platform quality was significantly higher in the high-quality condition than that in the low-quality condition (Mhigh-quality = 6.10, Mlow-quality = 3.02, t = 28.40, p < 0.001). Thus, the manipulation of platform quality was successful.

Realism check. Participants completed a seven-point realism check scale: “I can envision myself in the situation”. The results indicated that participants perceived the situation as highly realistic (M = 6.10, SD = 0.86).

4.2.4. Results of Hypotheses Testing

Regression analysis using PROCESS Model 4 with 5000 bootstrapped samples was conducted to test the effects of pricing strategy (0 = AIP, 1 = PP in Single) on WTP [47]. Platform quality is included as the covariate in analysis. As shown in Table 2, PP in Single (vs. AIP) significantly reduced both perceived value (β = −0.50, p < 0.001) and perceived price fairness (β = −0.83, p < 0.001). Thus, H1a and H2a were supported. Moreover, as expected, both perceived value (β = 0.81, p < 0.001) and perceived price fairness (β = 0.09, p < 0.05) showed positive effects on WTP, supporting H3 and H4.

Table 2.

PROCESS Model analysis results (experiment 1).

4.2.5. Post Hoc Analysis

Mediation effects. As shown in Appendix F (Table A5), a post hoc exploration of mediation effects showed that the indirect effect of pricing strategy on WTP via perceived value (path 1) or perceived price fairness (path 2) was significant, while the direct effect of pricing strategy on WTP was not significant, thus indicating the full mediation effects of perceived value and perceived price fairness.

Effects of platform quality. As shown in Table 2, in Model 4, platform quality as a covariate shows a significant direct effect on perceived value, perceived price fairness, and WTP. PROCESS Model 58 with 5000 bootstrapped samples was adopted to explore the moderation effect of platform quality. However, neither the effects of pricing strategy (X1 × W1) on perceived value and perceived price fairness nor the effects of perceived value (M1 × W1) and perceived price fairness (M2 × W1) on WTP were moderated by platform quality, suggesting that the effects of PP in Single (vs. AIP) are not significantly different between high-quality and low-quality video platforms.

4.2.6. Discussion

Experiment 1 revealed that PP in Single (vs. AIP) for subscription plans in terms of digital content platforms significantly reduced user-perceived value and perceived price fairness, which, in turn, reduced user WTP for such subscription plans. These effects were found after controlling the effect of platform quality and held whenever the platform quality was high or low. These results suggested that PP (i.e., PP in Single vs. AIP) influences user WTP beyond platform quality and that the effect of platform quality should be controlled when examining the consequences of PP (vs. AIP).

4.3. Experiment 2

4.3.1. Experiment Design and Procedure

Based on the results of experiment 1, experiment 2 compared the effect of each PP with that of AIP with a between-subject design on high-quality platforms, given the prevalence of PP on leading digital content platforms (e.g., YouTube, TikTok, Audible, and Tencent).

A total of 490 subjects (Mage = 34.9, 68.8% female; see Appendix B, Table A1 for demographic details) recruited from Credamo were randomly assigned to one of the four pricing conditions (i.e., AIP, PP in Single, PP in Combination, and PP in Blind Box). Subjects assumed that they would be purchasing a premium subscription plan to access movies on a fictitious high-quality video platform. The quality description of the platform was the same as that in experiment 1.

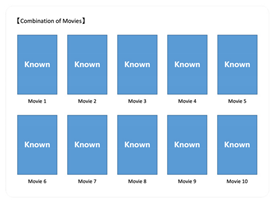

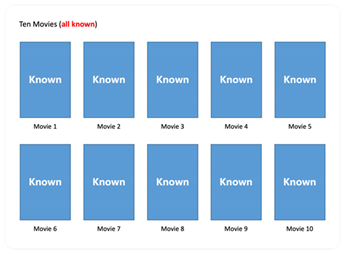

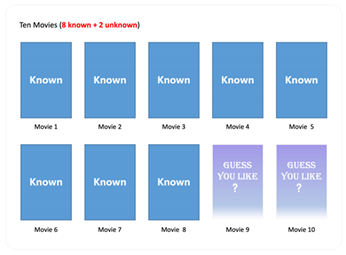

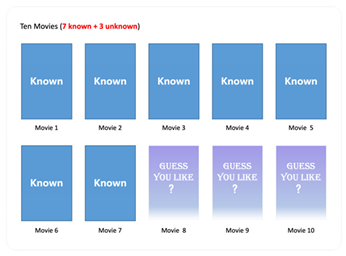

The pricing strategy was manipulated by providing subjects with four different premium subscription plans on a fictitious digital video platform. As shown in Appendix G (Table A6), the manipulation of AIP and PP in Single is the same as that in experiment 1. However, in the PP in Combination condition, subjects paid per standardized bundle of ten movie videos beyond a fixed membership fee, all of which were assumed to be known by users. In the PP in Blind Box condition, subjects paid per personalized bundle of ten movie videos beyond a fixed membership fee, half of which were assumed to be known by users, with the other half being recommended but unknown. This percentage of unknown videos was determined based on a pre-test (n = 75, see Table A7 and Table A8 in Appendix H) which showed that subjects’ perceived uncertainty in the Blind Box condition with 50 percent unknown was significantly higher than that in the condition with all known (t = 2.78, p < 0.01) (see Appendix H, Table A9).

The experimental procedure is the same as that of experiment 1. The measures exhibited high reliabilities (WTP, α = 0.917; perceived value, α = 0.929; perceived price fairness, α = 0.910) (see Appendix E, Table A4).

4.3.2. Manipulation and Realism Checks

Manipulation check. After reading the given scenario, subjects were asked to pick the surcharge plan described on the scenario (i.e., “free”, “pay-per-video”, “pay-per-standardized bundle”, and “pay-per-personalized bundle”). The results indicated that the manipulation of the pricing strategy was successful.

Realism check. Subjects judged the realism of the experimental scenarios on the same item as that in experiment 1. The result suggested that subjects perceived the experimental design as realistic (M = 6.16, SD = 0.81).

4.3.3. Results of Hypotheses Testing

Regression analysis using PROCESS Model 4 with 5000 bootstrapped samples was conducted to compare the effectiveness of AIP and another two innovative PP strategies. As shown in Table 3, as expected in H1b and H1c, the negative effects of PP in Combination (β = −0.68, p < 0.001) and PP in Blind Box (β = −0.77, p < 0.001) on perceived value were significant. In a similar vein, their significant and negative effects on perceived price fairness support H2b and H2c. In addition, H1a and H2a were confirmed in this experiment.

Table 3.

PROCESS Model analysis results (experiment 2).

4.3.4. Post Hoc Analysis

Mediation effects. As shown in Appendix I (Table A10), the post hoc exploration of mediation effects showed that the indirect effect of PP in Combination (vs. AIP) and PP in Blind Box (vs. AIP) on WTP via perceived value (path 1) and perceived price fairness (path 2) were significant. However, the direct effects of PP in Combination (vs. AIP) and PP in Blind Box (vs. AIP) on WTP were not significant, thus indicating the full mediating roles of perceived value and perceived price fairness.

Differential effects of PP strategies. A post hoc exploration of the different effects of the three PP strategies (i.e., PP in Single, PP in Combination, and PP in Blind Box) was conducted using PROCESS Model 4 with 5000 bootstrapped samples. As shown in Appendix J (Table A11), neither PP in Combination (vs. PP in Single) nor PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) showed a significant effect on perceived value, perceived price fairness, and WTP.

4.3.5. Discussion

Experiment 2 revealed that, similar to PP in Single, the two innovative PP strategies (i.e., PP in Combination and PP in Blind Box) are also inferior to AIP in increasing user-perceived value and perceived price fairness, which in turn reduces user WTP of subscription plans.

Moreover, as found in the post hoc analysis, PP in Combination and PP in Blind Box, relative to PP in Single, showed no differential effects on perceived value, perceived price fairness, and WTP. This finding, though not hypothesized, is somehow surprising because both PP in Combination and PP in Blind Box borrow the bundling idea of AIP to revise the presentation format of surcharges. A possible explanation for these seemingly nonsignificant effects could be the existence of opposite mediation effects (e.g., positive and negative mechanisms) or moderation effects (e.g., product type). Given that experiment 2 was conducted in the context of hedonic products (i.e., movies) and failed to compare the mechanisms specific to three PP strategies, it is theoretically and practically important to further explore the influencing mechanisms of these three PP strategies to account for their undifferentiated effects.

5. Study 2: Comparison of the Effects of PP Strategies

Given the undifferentiated effects of three PP strategies on user-perceived value and WTP in Study 1, Study 2 aims to explore why these three PP strategies show no differential effects despite being different in the presentation format of surcharges. Specifically, Study 2 focuses on examining their influence on user-perceived value because, as shown in Study 1, perceived value is a powerful predictor of user WTP for subscription plans on digital content platforms. Moreover, as shown in Figure 2, this study includes perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness as the mediators because the different presentation formats of surcharges may bring users new benefits (e.g., playfulness) and sacrifices (e.g., the effort to deal with price complexity) that determine users’ valuation of a pricing strategy. In addition, Study 2 extends the comparison of PP strategies from hedonic products (i.e., movies in Study 1) to utilitarian products through including product type as a moderator, given that users’ value assessment depends on the type of products.

5.1. Hypotheses

Perceived price complexity refers to the extent to which a price poses a high cognitive burden on users in their effort to make sense of the price components and to mathematically arrive at the final bill amount [48,49]. Perceived price complexity reflects users’ overall perception of price load (i.e., the number of prices), calculation effort (i.e., complex numerical stimuli), and evaluation effort (i.e., evaluate the benefits of an offer) [50].

The user-perceived price complexity of subscription plans under PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box is higher than that under PP in Single due to the increased calculation effort and evaluation effort. First of all, the presentation of a bundled price increases the difficulty of calculating the actual price of a certain product, especially when a bundle includes some undesired content products. Thus, users under PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) must invest more energy to estimate if they want to determine the accurate price of a single product before they purchase [51,52]. Secondly, probabilistic selling increases user-perceived difficulty in evaluating the bundled price against the benefits of a subscription plan. Users under PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) are not aware of the exact content until they purchase a subscription plan, thus increasing the difficulty of assessing the benefits of such a price [53].

User-perceived price complexity can lower user-perceived value regarding subscription plans due to increased non-monetary sacrifices. High perceived price complexity implies a higher cognitive burden and higher thinking costs for complicated information processing [54]. When perceiving a higher price complexity, users need to invest more energy to judge the final price [50], thus increasing their non-monetary sacrifices to purchase subscription plans. Consequently, higher perceived price complexity may lead to lower perceived value due to increased perceived sacrifices, assuming a given perceived benefit (e.g., the same paid videos). Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H5.

Compared with that under PP in Single, user-perceived price complexity is higher under (a) PP in Combination and (b) PP in Blind Box.

H6.

User-perceived price complexity is negatively related to user-perceived value.

Perceived playfulness refers to the extent to which users subjectively experience focus, curiosity, and enjoyment when interacting with the context [55]. It reflects users’ temporal evaluation of the playful state in the interaction [56]. Platforms can create the experience of playfulness through adding game-design elements that support users’ experience of focus, curiosity, and enjoyment [57].

Users’ perceived playfulness under PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box is higher than that under PP in Single due to the intrinsic attributes of playfulness of these two PP strategies. Under PP in Single condition, users have to search and find the content products of their interests based on their knowledge. However, bundling pricing can help users focus their attention on the content products [51,58]. For example, under PP in Combination conditions, the categorization and sale of content products by genre or usage occasions enable users to explore contents of the same theme intensively within a bundle [59]. Moreover, these deliberately created digital content product bundles based on various algorithms can urge users to be curious during the discovery within a bundle because users may discover new content beyond their current knowledge of the same theme [60,61]. In addition, the uncertainty associated with the probabilistic selling of bundled content products can make the purchasing of subscription plans a game. Under PP in Blind Box conditions, this game-based purchasing can not only arouse users’ curiosity about the personalized recommendations in a Blind Box [62] but also bring more enjoyment and excitement to users if they find surprises from the Blind Box, thus enhancing user-perceived playfulness [63].

User-perceived playfulness can positively influence user-perceived value of subscription plans due to increased taste benefits. Perceived playfulness can encourage users to generate more positive emotions (e.g., enjoyment, excitement, fun), thus increasing user emotional value [62,63]. This emotional value can increase user-perceived benefits regarding subscription plans, which in turn increases user-perceived value. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H7.

Compared with that under PP in Single, user-perceived playfulness is higher under (a) PP in Combination and (b) PP in Blind Box.

H8.

User-perceived playfulness is positively related to user-perceived value.

Product type affects users’ value evaluation due to the induced different decision focus [25]. Users are more sensitive to price complexity when purchasing subscription plans to access utilitarian content products due to the accuracy of price calculation [64]. However, when purchasing subscription plans for hedonic content products, the emotional value is the focus of users and they are less sensitive to the non-monetary sacrifice caused by price complexity. In this vein, the sacrifice-increase disadvantage is less likely to be recognized when users purchase subscription plans for hedonic products (vs. utilitarian products). Thus, it is expected that the negative effect of perceived price complexity on perceived value is less salient for hedonic products (vs. utilitarian products).

Offering taste benefits to increase emotional value, such as pleasant experiences, surprises, adventure, and enjoyment, is the beneficial advantage of adding playfulness elements in subscription plans. This advantage is more likely to be recognized by users when purchasing subscription plans to access hedonic content products (vs. utilitarian products) [65,66]. This is because, regarding the hedonic content products, users place more weight on the taste benefits which increase their perceived emotional value [62,64]. Thus, it is expected that the positive effect of perceived playfulness on perceived value is more salient for hedonic products (vs. utilitarian products). Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H9.

Product type moderates the (a) negative effects of user-perceived price complexity and (b) the positive effects of user-perceived playfulness on perceived value. That is, the negative effect of user-perceived price complexity on user-perceived value is weakened for hedonic products (vs. utilitarian products), while the positive effect of user-perceived playfulness on user-perceived value is greater for hedonic products (vs. utilitarian products).

5.2. Experiment 3

5.2.1. Experiment Design and Procedure

Experiment 3 used a 3 (PP strategy: PP in Single, PP in Combination, and PP in Blind Box) × 2 (product type: utilitarian vs. hedonic) between-subject design. A total of 730 subjects (Mage = 35.3, 68.2% female; see Appendix B, Table A1 for demographic details) recruited from Credamo were randomly assigned to one of the six scenarios, as presented in Table 4. Subjects assumed that they would be purchasing a premium subscription plan to access paid videos on a fictitious high-quality video platform.

Table 4.

Experimental setup.

The product type was manipulated by providing subjects with the description of two types of digital video products. The hedonic product condition involved subscribing for entertainment purposes, i.e., movies, whereas the utilitarian product condition involved subscribing for utilitarian purposes, i.e., online training courses. The manipulation of the three PP strategies, the quality description of the platform, and the experimental procedure were the same as those in experiment 2 (see Appendix K, Table A12).

5.2.2. Measures

Perceived price complexity was measured with three dimensions (α = 0.900 for price load, α = 0.920 for calculation effort, and α = 0.907 for evaluation effort) adapted from Homburg et al. [50]. Perceived playfulness was measured with six items (α = 0.940) adapted from Hamari and Koivisto [67]. The measures for other constructs were the same as those in experiment 2 (perceived value, α = 0.931; perceived price fairness, α = 0.911) (see Appendix E, Table A4).

5.2.3. Manipulation and Realism Checks

Manipulation check. After reading the given scenario, subjects were asked to pick the surcharge plan described in the scenario (i.e., “pay-per-video”, “pay-per-standardized bundle”, and “pay-per-personalized bundle”). They also picked the subscribed products in the scenario (i.e., “movies” and “online course”). All subjects correctly answered these questions, indicating the successful manipulation of PP strategy and product type.

Realism check. The realism check of this study was the same as that of experiment 2. The results revealed that subjects perceived the experimental design as being realistic (M = 6.12, SD = 0.88).

5.3. Results

Direct and indirect effects. Regression analysis using PROCESS Model 4 with 5000 bootstrapped samples was conducted to examine the difference between three PP strategies (0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination, 2 = PP in Blind Box). As shown in Table 5, as predicted in H5a and H5b, the effects of PP in Combination (β = 0.26, p < 0.05) and PP in Blind Box (β = 0.47, p < 0.001) on users’ perception of price complexity were significant. Similarly, their significant effects on users’ perception of playfulness support H7a and H7b. In addition, user-perceived price complexity (β = −0.38, p < 0.001) and perceived playfulness (β = 0.44, p < 0.001) show opposite effects on user-perceived value, thus supporting H6 and H8.

Table 5.

PROCESS Model analysis results (experiment 3).

As shown in Appendix L (Table A13), the post hoc exploration of mediation effects showed the significant indirect effect of PP in Combination (vs. PP in Single) and PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) on user-perceived value via perceived price complexity (path 1) and perceived playfulness (path 2). However, the direct effect of PP in Combination (vs. PP in Single) on perceived value was not significant, whereas the direct effect of PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) on perceived value was significant, thus suggesting full and partial mediation effects for PP in Combination (vs. PP in Single) and PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single), respectively.

Moderation effects. To test the moderating role of product type (0 = utilitarian, 1 = hedonic), PROCESS Model 14 with 5000 bootstrapped samples was utilized [47]. As shown in Table 5, the interactional effects between PP strategy and product type were not significant, thus not supporting H9a and H9b.

5.4. Discussion

Study 2 compared the influencing mechanisms of three PP strategies for subscription plans on high-quality digital content platforms. The results showed that both user-perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness were higher under PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) conditions. However, user-perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness had negative and positive effects on user-perceived value, respectively. This offsetting effect helps to account for the undifferentiated effects of PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) on perceived value. In addition, the effects of perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness on perceived value were not moderated by product type in the current study.

6. Conclusions and General Discussion

6.1. Conclusions

This research, with three experiments, finds that all three PP strategies of subscription plans are inferior to AIP in increasing user WTP, though they show different influencing mechanisms on user-perceived value. First of all, compared with PP, AIP is more effective because it can increase user-perceived value and the perceived price fairness of subscription plans. This finding supports Alaei et al. [1]’s and Datta et al. [5]’s insights into the subscription business of digital content platforms. However, although this finding implies the advantage of AIP (vs. PP) from a user perspective, it does not necessarily suggest that digital content platforms, especially high-quality platforms, should abandon PP without any other business considerations.

Secondly, user-perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness are two key underlying mechanisms to account for when evaluating the effects of three PP strategies on users’ valuation of subscription plans. Compared with those under PP in Single conditions, both perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness are higher under PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box. Although both these two PP strategies (vs. PP in Single) can increase user-perceived value via increased perceived playfulness, these positive indirect effects can be offset by the negative indirect effects on perceived value via user-perceived price complexity. This offsetting effect partially accounts for the nonsignificant total effect of PP in Combination or PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) on perceived value.

Lastly, the effects of PP strategies for subscription plans on user WTP are relatively consistent on digital content platforms. Pricing strategy, in addition to platform quality, shows significant effects on WTP. The inferiority of PP in Single (vs. AIP) held whenever the platform quality was high or low. Moreover, the indirect effects of PP strategies on perceived value hold across product types. A possible explanation for this unexpected finding could be that neither the perceived non-monetary sacrifices nor the perceived taste benefits are as significant as expected, given the powerful online search functions of most digital content platforms and the lack of the actual prices being presented in the experiments.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

There are several theoretical implications. Firstly, this study contributes to our understanding of pricing in subscription-based businesses. Despite the increasing research on AIP or PP, only a limited number of studies have simultaneously compared the influencing mechanisms of these two pricing strategies for subscription-based businesses. This research enriches the current knowledge of the subscription business model for digital content platforms through comparing the influencing mechanisms of PP and AIP on user WTP. It reveals that user-perceived value and perceived price fairness are two important mediators to account for when evaluating the pricing effects of subscription plans regardless of platform quality.

Secondly, this research extends the literature on PP strategies. Previous studies suggest that the effectiveness of PP depends on the presentation format of the price and the level, amount, and fairness of the surcharges [7,8,12,18,68]. This research sheds light on the influencing mechanisms of three PP strategies on users’ perceived value on digital content platforms. It demonstrates that perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness are two key mechanisms to examine in regard to the effectiveness of revising the presentation format of surcharges (e.g., PP in Single, PP in Combination, and PP in Blind Box) on high-quality digital content platforms.

Lastly, it empirically contributes to the understanding of the boundary effects of pricing digital content products. This research explores the pricing effects in different contexts of digital content products (i.e., high-quality platforms vs. low-quality platforms, utilitarian products vs. hedonic products). The empirical results suggest that the value–fairness mechanism and the playfulness–price complexity mechanism for examining pricing effects are valid across platform quality and product types, respectively.

6.3. Practical Implications

The study also offers practical insights for digital content platforms aiming to formulate effective subscription-based pricing strategies to gain more profits through encouraging users’ favorable perception and responses. Firstly, digital content platforms need to carefully adopt the PP strategy for their subscription plans due to their connection with both content product providers and users. Some digital content providers expect the platforms to adopt the PP strategy so that they may maximize the profits from their published digital content products, especially copyrighted products. Platforms may also profit more from the subscription business with the adoption of the PP strategy. However, platforms should be cautious that the PP-based subscription plan, relative to the plan with an AIP strategy, can lower users’ perception of value and price fairness, which in turn decreases their willingness to subscribe. Thus, if the PP strategy is adopted, it is wise for digital content platforms to account for the surcharges reasonably, such as covering the costs of additional services or requests by product providers.

Secondly, digital content platforms can increase the effectiveness of the PP strategy of subscription plans through reducing price complexity. When pricing by digital content product bundles, it is wise for digital content platforms to label the actual price of a single product in a bundle to lower users’ cognitive burden and calculation effort. For example, the presentation of the actual price of digital content products should contain fewer components or indicate savings explicitly. Moreover, digital content platforms that already use the bundling strategy can present the final price or average price of each item in a bundle to lower users’ efforts in regard calculating costs.

Finally, digital content platforms can add more attributes of playfulness when pricing for bundles, such as creating more criteria to group content products (e.g., themes, genres, applications, fields, and user-generated tags). In addition, digital content platforms can apply the probabilistic selling technique to the personalized bundles of digital content products. These approaches, compared with PP in Single, make the content product bundles playful and attractive to users, though they require the platforms to improve their capabilities regarding personalized recommendations and pricing.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

This research should be considered in light of some limitations. First, this research focused on the effect of the surcharge format of a subscription-based pricing strategy on user WTP. However, other characteristics of surcharges (e.g., actual price, types, and reasonableness) may affect the effectiveness of the pricing strategy. For example, different surcharge discounts (e.g., 50% off) may reduce the user-perceived cost of hedonic digital content product bundles. Future research can utilize other methods (e.g., conjoint analysis) to explore the integrative effects of surcharges and platform offerings.

Second, the empirical test of three PP strategies was conducted in a specific hypothetical bundling context (i.e., ten items with all or a half known) from a user perspective. Although this context supported the goal of the current research, the size of a bundle or the proportion of unknown items in a bundle may affect user reactions, which warrants further investigation. Future research can take advantage of real datasets from digital content platforms to explore the effects of PP strategies from an integrative perspective, for example, how the PP strategies affect users’ subscription behavior and subscription revenues, while considering platform service costs and content providers’ demands. Moreover, it is necessary to examine the proposed model of PP strategies in other region or countries, given that digital consumption behavior may vary across countries.

Third, this research examined the value difference in PP strategy based on the mechanisms of perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness in new subscription plan purchasing. It is important for future research to explore the mechanisms of PP in other subscription occasions, such as subscription plan renewal or change. Moreover, the partial mediating roles of perceived price complexity and perceived playfulness for PP in Blind Box (vs. PP in Single) imply that it is promising in terms of further exploring new mechanisms to account for the effect of PP in Blind Box on perceived value.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., C.S. and L.C.; Methodology, C.S.; Investigation, C.S. and J.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.S.; Writing—Review & Editing, J.K. and C.S.; Funding Acquisition, J.K. and L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Innovation Centre for Digital Business and Capital Development of Beijing Technology and Business University (SZSK202320) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71772059).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Pricing Strategy of Top Three Apps by Category on the Apple Store. Note. Data updated on 10 June 2024.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Demographics of Subjects.

Table A1.

Demographics of Subjects.

| Demographics | Experiment 1 (N = 538, April 2024) | Experiment 2 (N = 490, May 2024) | Experiment 3 (N = 730, June 2024) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 173 | 32.2% | 153 | 31.2% | 232 | 31.8% |

| Female | 365 | 67.8% | 337 | 68.8% | 498 | 68.2% |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–24 | 68 | 12.6% | 38 | 7.8% | 59 | 8.1% |

| 25–34 | 245 | 45.5% | 223 | 45.5% | 326 | 44.7% |

| 35–44 | 159 | 29.6% | 171 | 34.9% | 245 | 33.6% |

| 45–54 | 52 | 9.7% | 45 | 9.2% | 68 | 9.3% |

| 55+ | 14 | 2.6% | 13 | 2.7% | 32 | 4.4% |

| Education | ||||||

| High school or lower | 31 | 5.8% | 24 | 4.9% | 42 | 5.8% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 398 | 74% | 351 | 71.6% | 522 | 71.5% |

| Master’s degree | 99 | 18.4% | 109 | 22.2% | 161 | 22.1% |

| Doctoral degree | 10 | 1.9% | 6 | 1.2% | 5 | 0.7% |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Student | 40 | 7.4% | 30 | 6.1% | 47 | 6.4% |

| Employed by public institutions | 124 | 23% | 124 | 25.3% | 190 | 26% |

| Employed by companies | 362 | 67.3% | 330 | 67.3% | 480 | 65.8% |

| Other | 12 | 2.2% | 6 | 1.2% | 13 | 1.8% |

| Monthly income (yuan) | ||||||

| <2000 | 21 | 3.9% | 16 | 3.3% | 30 | 4.1% |

| 2000–4000 | 45 | 8.4% | 34 | 6.9% | 50 | 6.8% |

| 4001–6000 | 64 | 11.9% | 53 | 10.8% | 98 | 13.4% |

| 6001–8000 | 81 | 15.1% | 92 | 18.8% | 122 | 16.7% |

| 8001–10,000 | 113 | 21% | 107 | 21.8% | 145 | 19.9% |

| >10,000 | 214 | 39.8% | 188 | 38.4% | 285 | 39% |

Appendix C

Table A2.

Experimental Stimuli (Experiment 1).

Table A2.

Experimental Stimuli (Experiment 1).

| Pricing Strategy | PP in Single | AIP |

This video platform introduces a VIP subscription plan:

| This video platform introduces a VIP subscription plan:

| |

| Platform Quality | High-quality | Low-quality |

This video platform:

| This video platform:

|

Note. PP = partitioned pricing. AIP = all-inclusive pricing.

Appendix D

In this online survey of the determinants of platform quality, a total of 30 valid responses were collected from recruited respondents on Credamo (https://www.credamo.com/#/, a professional marketing research platform based in China).

During this survey, respondents were asked to choose one or more of the ten determinants that potentially affect the quality of digital video platforms. These ten determinants and results are shown in Table A3.

The results showed that the four determinants of the quality of digital video platforms were voted on by more than half of the respondents. These four determinants include the number of copyrighted resources, the quality of exclusive content, the user base, and the new content products that are launched.

Table A3.

Results of pre-test.

Table A3.

Results of pre-test.

| Determinants of Platform Quality | Number of Votes |

|---|---|

| Number of copyrighted resources | 23 |

| Quality of exclusive content | 22 |

| User base | 18 |

| New content product launch | 18 |

| Variety of content | 14 |

| Video resolution | 11 |

| Advertising experience | 8 |

| Simplicity of the interface | 7 |

| Number of original videos | 7 |

| Personalized recommendation | 2 |

Appendix E

Table A4.

Measurement Items.

Table A4.

Measurement Items.

| Measures | Cronbach’s α | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Experiment 2 | Experiment 3 | |

| Willingness to Purchase | 0.960 | 0.917 | |

| If I were going to play some paid videos, I would consider purchasing this subscription plan. | |||

| I am willing to become a VIP subscriber for the paid videos. | |||

| I am likely to become a VIP subscriber for the paid videos. | |||

| Perceived Price Fairness | 0.945 | 0.910 | 0.911 |

| I think the pricing of this subscription plan is... | |||

| ..justified. | |||

| ...satisfactory. | |||

| ...acceptable. | |||

| Perceived Value | 0.966 | 0.929 | 0.931 |

| If I purchased this VIP subscription plan, I think this subscription plan is... | |||

| A good deal. | |||

| Highly unreasonable. | |||

| Very worthwhile. | |||

| Extremely good value. | |||

| Perceived price complexity | |||

| Price load | 0.900 | ||

| I had a hard time understanding this VIP subscription plan. | |||

| I would need to know a lot to understand this VIP subscription plan. | |||

| This VIP subscription plan looks very complicated to me. | |||

| It was difficult for me to obtain an overview of the price of this VIP subscription plan. | |||

| Calculation effort | 0.920 | ||

| It was tough to calculate the total price. | |||

| It was difficult for me to cope with the single numbers. | |||

| I concentrated a lot to carry out the many different calculations. | |||

| It was difficult to determine the overall price without a calculator. | |||

| Evaluation effort | 0.907 | ||

| It was difficult to deal with this VIP subscription plan. | |||

| I had to concentrate a lot to evaluate this VIP subscription plan. | |||

| It took a lot of time to evaluate this VIP subscription plan, and to make a decision. | |||

| Playfulness | 0.940 | ||

| I think this subscription plan is... | |||

| Playful. | |||

| Curious. | |||

| Creative. | |||

| Flexible | |||

| Experimenting. | |||

| Spontaneous. | |||

Appendix F

Table A5.

Results of Mediation Analysis (Experiment 1).

Table A5.

Results of Mediation Analysis (Experiment 1).

| Total Effect | |||

| Pricing Strategy → WTP | |||

| Effect | BootSE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| −0.42 | 0.16 | −0.73 | −0.11 |

| Indirect effect | |||

| Path1: Pricing strategy → Perceived value → WTP | |||

| Effect | BootSE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| −0.41 | 0.10 | −0.60 | −0.22 |

| Path2: Pricing strategy → Perceived price fairness → WTP | |||

| Effect | BootSE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| −0.07 | 0.04 | −0.16 | −0.01 |

| Direct effect: Pricing strategy → WTP | |||

| Effect | SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| 0.10 | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.21 |

Note. Pricing strategy: 0 = AIP strategy, 1 = PP in Single strategy.

Appendix G

Table A6.

Examples of the Experimental Stimuli of Pricing Strategy (Experiment 2).

Table A6.

Examples of the Experimental Stimuli of Pricing Strategy (Experiment 2).

| PP Strategy | AIP | PP in Single | PP in Combination | PP in Blind Box |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Type | Hedonic | Hedonic | Hedonic | Hedonic |

| Instruction | In this plan, you need to pay a fixed membership fee to access all paid movies. | In this plan, you need to pay-per-video to access a certain selective movie beyond the fixed membership fee. | In this plan, you need to pay-per-standardized bundle of ten videos to access these certain selective online training courses beyond the fixed membership fee. | In this plan, you need to pay-per-personalized bundle of ten videos to access these certain selective movies beyond the fixed membership fee. |

| Examples |  |  |  |  |

Appendix H

Seventy-five subjects were recruited on Credamo. They read four bundles of 10 videos sequentially. Each of these bundles includes a given number of unknown video items (i.e., 0, 2, 3, 5) (see Table A7). These four bundles were presented to the subjects in a random order. After reading each bundle, subjects indicated their perceived uncertainty towards that bundle on a three-item scale adapted from Dowling and Staelin [69] (see Table A8).

A series of paired-sample t tests were conducted to compare the perceived uncertainty between bundles. As shown in Table A9, the subjects’ perceived uncertainty of the bundle with five unknown videos is significantly higher than that of the bundle with zero unknown video (t = 2.78, p < 0.01). However, subjects’ perceived uncertainty of the bundle with two or three unknown videos was not significantly different from that of the bundle with zero unknown videos.

Table A7.

Experimental stimuli in the pre-test (Experiment 2).

Table A7.

Experimental stimuli in the pre-test (Experiment 2).

| A Bundle with Zero Unknown Videos | A Bundle with Two Unknown Videos |

|  |

| A Bundle with Three Unknown Videos | A Bundle with Five Unknown Videos |

|  |

Table A8.

Measurement for perceived uncertainty (Experiment 2).

Table A8.

Measurement for perceived uncertainty (Experiment 2).

| Measures of Perceived Uncertainty | Cronbach’s α | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Unknown Video | 2 Unknown Video | 3 Unknown Video | 5 Unknown Video | |

| I cannot clearly know about the content of videos in the bundle. | ||||

| I am not sure that whether the videos in the bundle meet my expectations. | ||||

| There is a great deal of uncertainty regarding the videos in the bundle for me. | 0.920 | 0.931 | 0.948 | 0.926 |

| I am not sure that whether the videos in the bundle meet my expectations. | ||||

| There is a great deal of uncertainty regarding the videos in the bundle for me. | ||||

Table A9.

Paired-sample t test (Experiment 2).

Table A9.

Paired-sample t test (Experiment 2).

| Mean | SD | LLCI | ULCI | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair 1 Q2 − Q0 | −0.17 | 1.77 | −0.58 | 0.24 | −0.83 |

| Pair 2 Q3 − Q0 | 0.01 | 1.69 | −0.38 | 0.40 | 0.05 |

| Pair 3 Q5 − Q0 | 0.57 | 1.79 | 0.16 | 0.98 | 2.78 |

Note. Q0, Q2, Q3, and Q5 denote zero, two, three, and five unknown videos in a bundle, respectively.

Appendix I

Table A10.

Results of Mediation Analysis (Experiment 2).

Table A10.

Results of Mediation Analysis (Experiment 2).

| Total Effect | ||||

| PP Strategy → WTP | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X1 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 1 = PP in Single) | −0.61 | 0.16 | −0.91 | −0.30 |

| X2 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 2 = PP in Combination) | −0.75 | 0.16 | −1.06 | −0.44 |

| X3 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 3 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.82 | 0.16 | −1.13 | −0.51 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Path1: PP strategy → Perceived value → WTP | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X1 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 1 = PP in Single) | −0.41 | 0.10 | −0.61 | −0.22 |

| X2 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 2 = PP in Combination) | −0.50 | 0.11 | −0.73 | −0.29 |

| X3 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 3 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.57 | 0.12 | −0.80 | −0.34 |

| Path2: PP strategy → Perceived price fairness → WTP | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X1 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 1 = PP in Single) | −0.12 | 0.05 | −0.23 | −0.04 |

| X2 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 2 = PP in Combination) | −0.12 | 0.05 | −0.23 | −0.04 |

| X3 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 3 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.13 | 0.05 | −0.25 | −0.05 |

| Direct effect: PP strategy → WTP | ||||

| Effect | SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X1 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 1 = PP in Single) | −0.08 | 0.08 | −0.23 | 0.07 |

| X2 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 2 = PP in Combination) | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.29 | 0.02 |

| X3 (PP strategy: 0 = AIP, 3 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.12 | 0.08 | −0.27 | 0.03 |

Appendix J

Table A11.

Results of Differential Effects of PP Strategies (Experiment 2).

Table A11.

Results of Differential Effects of PP Strategies (Experiment 2).

| Perceived Value | Perceived Price Fairness | WTP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | −0.13 | 0.01 | −0.05 | |

| X5 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.22 | −0.07 | −0.04 | |

| M3 (Perceived value) | 0.77 *** | |||

| M4 (Perceived price fairness) | 0.14 ** | |||

| Constant | 5.33 *** | 5.13 *** | 0.53 *** | |

| R2 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.80 | |

| Total effect | ||||

| PP strategy → WTP | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | −0.15 | 0.17 | −0.48 | 0.19 |

| X5 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.21 | 0.17 | −0.55 | 0.12 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Path1: PP strategy → Perceived value → WTP | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | −0.10 | 0.13 | −0.35 | 0.15 |

| X5 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.17 | 0.13 | −0.43 | 0.09 |

| Path2: PP strategy → Perceived price fairness→ WTP | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | 0.002 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.05 |

| X5 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.05 |

| Direct effect: PP strategy → WTP | ||||

| Effect | SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | −0.05 | 0.08 | −0.21 | 0.10 |

| X5 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.19 | 0.12 |

Note. N = 367. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Appendix K

Table A12.

Examples of the Experimental Stimuli of PP Strategy (Experiment 3).

Table A12.

Examples of the Experimental Stimuli of PP Strategy (Experiment 3).

| PP Strategy | PP in Single | PP in Combination | PP in Blind Box |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product Type | Hedonic | Utilitarian | Hedonic |

| Instruction | In this plan, you need to pay-per-video to access a certain selective movie beyond the fixed membership fee. | In this plan, you need to pay-per-standardized bundle of ten videos to access these certain selective online training courses beyond the fixed membership fee. | In this plan, you need to pay-per-personalized bundle of ten videos to access these certain selective movies beyond the fixed membership fee. |

| Examples |  |  |  |

Appendix L

Table A13.

Results of Mediation Analysis (Experiment 3).

Table A13.

Results of Mediation Analysis (Experiment 3).

| Total Effect | ||||

| PP Strategy → Perceived Value | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X3 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | −0.03 | 0.11 | −0.25 | 0.20 |

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.20 | 0.11 | −0.43 | 0.02 |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Path1: PP strategy →Perceived price complexity →Perceived value | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X3 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | −0.09 | 0.04 | −0.19 | −0.01 |

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.18 | 0.05 | −0.28 | −0.08 |

| Path2: PP strategy → Perceived playfulness → Perceived value | ||||

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X3 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.26 |

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.34 |

| Direct effect: PP strategy → Perceived value | ||||

| Effect | SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | |

| X3 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 1 = PP in Combination) | −0.08 | 0.08 | −0.23 | 0.07 |

| X4 (PP strategy: 0 = PP in Single, 2 = PP in Blind Box) | −0.26 | 0.08 | −0.41 | −0.10 |

References

- Alaei, S.; Makhdoumi, A.; Malekian, A. Optimal subscription planning for digital goods. Oper. Res. 2023, 71, 2245–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, R.; Park, Y.-H.; Yu, Q. The impact of subscription programs on customer purchases. J. Mark. Res. 2022, 59, 1101–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chan, T.Y.; Luo, X.; Wang, X. Time-inconsistent preferences and strategic self-control in digital content consumption. Mark. Sci. 2022, 41, 616–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. Analysis of online platforms’ free trial strategies for digital content subscription. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 2107–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, H.; Knox, G.; Bronnenberg, B.J. Changing their tune: How consumers’ adoption of online streaming affects music consumption and discovery. Mark. Sci. 2018, 37, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Herrman, A.; Bauer, H.H. The effects of price bundling on consumer evaluations by product offerings. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1999, 16, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Monroe, K.B. Price partitioning on the internet. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, S.; Bao, Y.; Pan, Y. Partitioning or bundling? Perceived fairness of the surcharge makes a difference. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 1025–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.W.; Sundararajan, A. Pricing digital goods: Discontinuous costs and shared infrastructure. Inf. Syst. Res. 2011, 22, 721–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. Pricing of Digital Products and Services in the Manufacturing Ecosystem. November 2020. Available online: https://www.studocu.com/in/document/amity-university/master-in-business-management/ipc-pricing-of-digital-products-final/66129397 (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- Morwitz, V.G.; Greenleaf, E.A.; Johnson, E.J. Divide and prosper: Consumers’ reactions to partitioned prices. J. Mark. Res. 1998, 35, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J.P.; Weathers, D. Examining differences in consumer reactions to partitioned prices with a variable number of price components. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Lee, J.; Baumann, C.; Kang, C. Fairness perception of ancillary fees: Industry differences and communication strategies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.W.; Srivastava, J. When 2 + 2 is not the same as 1 + 3: Variations in price sensitivity across components of partitioned prices. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Roy, R. How self-construal guides preference for partitioned versus combined pricing. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völckner, F.; Rühle, A.; Spann, M. To divide or not to divide? The impact of partitioned pricing on the informational and sacrifice effects of price. Mark. Lett. 2012, 23, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Madhavaram, S.R.; Park, H.Y. The role of hedonic and utilitarian motives on the effectiveness of partitioned pricing. J. Retail. 2020, 96, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jain, S.; Kannan, P.K. Optimal design of free samples for digital products and services. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Whether to add a digital product into subscription service? J. Theor. Appl. Electron.Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 921–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaldoss, W.; Du, J.; Shin, W. Media platforms’ content provision strategy and source of profits. Mark. Sci. 2021, 40, 395–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Gong, S.; Li, X. Co-Opetitive strategy optimization for online video platforms with multi-homing subscribers and advertisers. J. Theor. Appl. Electron.Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 744–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiati, V.; Rasouli, S.; Timmermans, H. Bundling, pricing schemes and extra features preferences for mobility as a service: Sequential portfolio choice experiment. Transp. Res. Part A -Policy Pract. 2020, 131, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, C. Building the value of next-generation platforms: The paradox of diminishing returns. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 3038–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, T.; Shankar, V. Are multichannel customers really more valuable? The moderating role of product category characteristics. J. Mark. 2013, 77, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wang, Y.; Mou, J. Enjoy to read and enjoy to shop: An investigation on the impact of product information presentation on purchase intention in digital content marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 76, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yildirim, P.; Zhang, Z.J. Implications of revenue models and technology for content moderation strategies. Mark. Sci. 2022, 41, 831–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, B. An empirical analysis of consumer purchase decisions under bucket-based price discrimination. Mark. Sci. 2015, 34, 646–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlereth, C.; Skiera, B.; Wolk, A. Measuring consumers’ preferences for metered pricing of services. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Venkatesh, R.; Mahajan, V. Optimal bundling of technological products with network externality. Manag. Sci. 2010, 56, 2224–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacheva, A.; Nikolova, H.; Lamberton, C. Will he buy a surprise? Gender differences in the purchase of surprise offerings. J. Retail. 2022, 98, 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Yu, Y. Sell probabilistic goods? A behavioral explanation for opaque selling. Mark. Sci. 2014, 33, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydock, C.; Wathieu, L. Not just about price: How benefit focus determines consumers’ retailer pricing strategy preference. J. Consum. Res. 2023, 50, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaweera, C.; Karjaluoto, H. The impact of service bundles on the mechanism through which functional value and price value affect WOM intent. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Ye, L.; Huang, W.; Ye, M. Understanding FinTech platform adoption: Impacts of perceived value and perceived risk. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1893–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.B.; Galletta, D.F. Consumer perceptions and willingness to pay for intrinsically motivated online content. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 2006, 23, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-W.; Lu, H.-P. Factors influencing online music purchase intention in Taiwan: An empirical study based on the value-intention framework. Internet Res. 2007, 17, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, L.E.; Warlop, L.; Alba, J.W. Consumer perceptions of price (un)fairness. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 29, 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]