Evolving Consumer Preferences: The Role of Attribute Shifts in Online Travel Agency Satisfaction and Loyalty

Abstract

1. Introduction

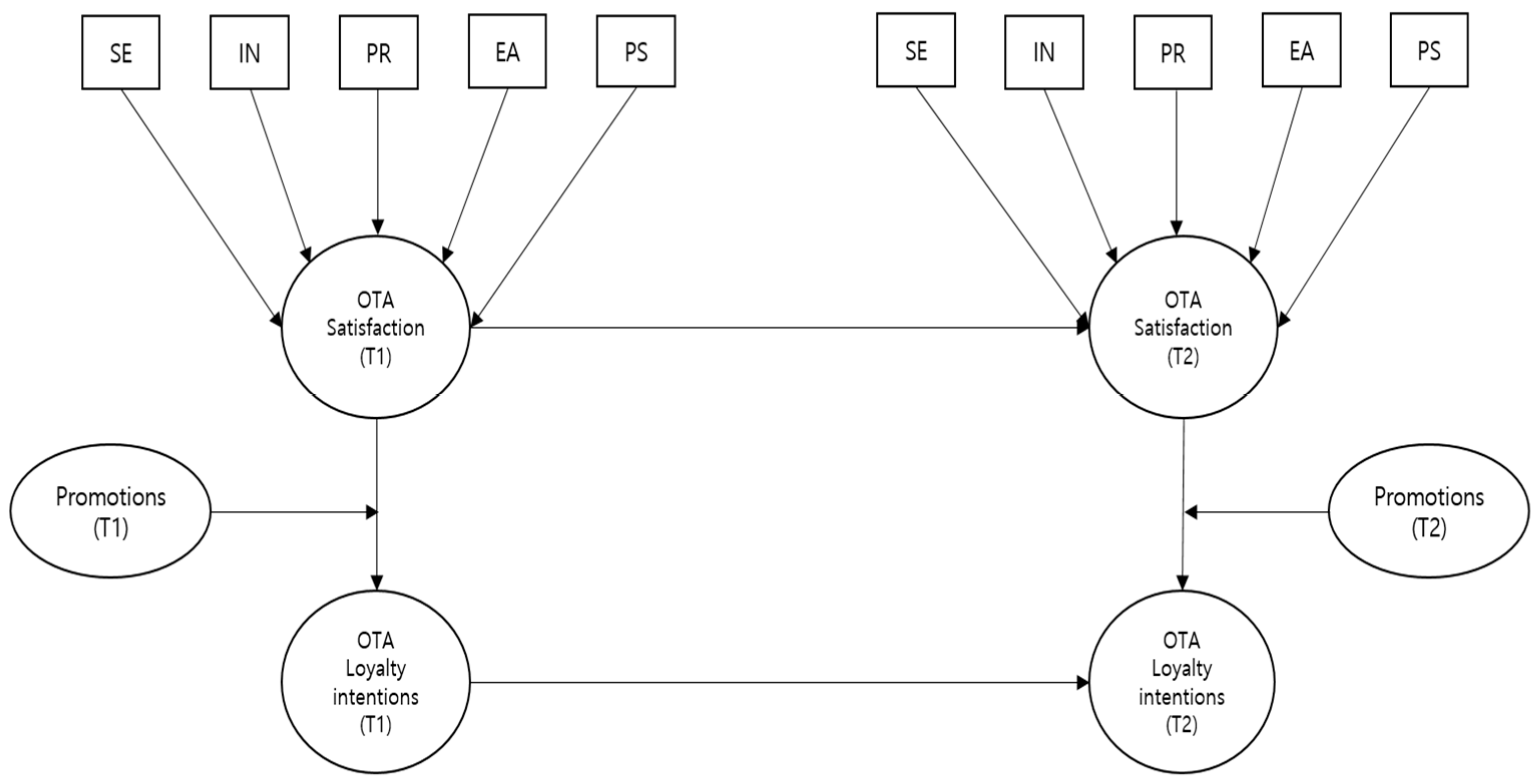

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. The Linkage Between OTA Selection Attributes and Satisfaction over Time

2.2. The Satisfaction-Loyalty Intentions Linkage over Time

2.3. The Moderating Role of Sales Promotions

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Measurement Comparison

3.4. Common Method Bias

3.5. Control Variables

3.6. Analytic Approach and Measurement Validity

4. Results

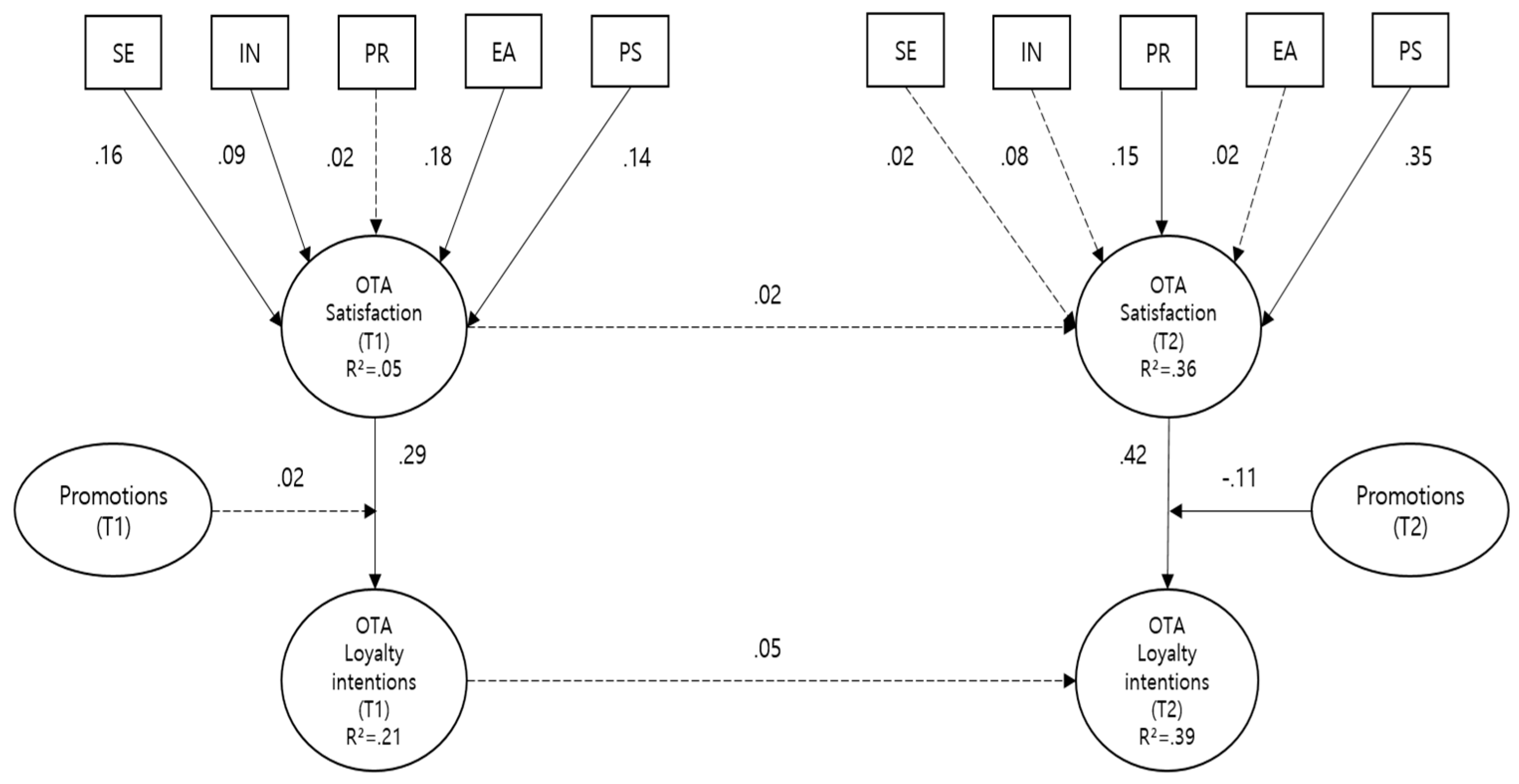

Model Estimates

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary and a Brief Literature Discussion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shepherd, J. Evolution of Customer Loyalty in the Travel and Hospitality Industry, Post COVID-19. 2022. Available online: https://www.capgemini.com/gb-en/insights/expert-perspectives/evolution-of-customer-loyalty-in-the-travel-and-hospitality-industry-post-covid-19/ (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. Prioritization of the Hotel Attributes according to Their Influence on Satisfaction: A Comparison of Two Techniques. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodet, G.; Anaba, V.; Bouchet, P. Hotel Attributes and Consumer Satisfaction: A Cross-country and Cross-hotel Study. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Kumar, V. Hotel Attributes and Overall Customer Satisfaction: What Did COVID-19 Change? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 40, 100867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Polisetty, A.; Mishra, A.; Rana, N.P. A Longitudinal Study on How Smart Tourism Technology Influences Tourists’ Repeat Visit Intentions. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 1380–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H. The Effects of Online Shopping Attributes on Satisfaction-Purchase Intention Link: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.C.; Li, G.; Song, H. Economic Analysis of Tourism Consumption Dynamics: A Time-Varying Parameter Demand System Approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 667–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Kim, W.G.; Han, J. A Perceptual Mapping of Online Travel Agencies and Preference Attributes. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, E.C.S.; Fan, Y.W. The Decision Making in Selecting Online Travel Agencies: An Application of Analytic Hierarchy Process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicksono, T.; Illes, C.B. Investigating Priority Service Attribute for Online Travel Agencies (OTA) Mobile App Development Using AHP Framework. J. Tour. Econ. 2022, 5, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. A Comparative Study on Travelers’ Online Travel Agency (OTA) Selection Attributes and Revisit Selection Attributes. Manag. Inf. Syst. Rev. 2018, 37, 175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Bergkvist, L.; Eisend, M. The Dynamic Nature of Marketing Constructs. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 521–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lv, X.; Scott, M. Understanding the Dynamics of Destination Loyalty: A Longitudinal Investigation into the Drivers of Revisit Intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V.; Kumar, P.; Tsiros, M. Attribute-Level Performance, Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions over Time: A consumption-system approach. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, A.; Mariani, M.M. Introducing the Dynamic Destination Satisfaction Method: An Analytical Tool to Track Tourism Destination Satisfaction Trends with Repeated Cross-Sectional Data. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 965–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jang, S.; Kang, S.; Kim, S. Why are Hotel Room Prices Different? Exploring Spatially Varying Relationships between Room Price and Hotel Attributes. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, S.; Dhir, A.; Kaur, P.; Mäntymäki, M. Why Do People Purchase from Online Travel Agencies (OTAs)? A Consumption Values Perspective. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; M.E. Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Reidenbach, R.E.; Oliva, T.A. General Living Systems Theory and Marketing: A Framework for Analysis. J. Mark. 1981, 45, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F. The Evolution of Loyalty Intentions. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, C.; Mccabe, S.; Xu, H. Always Best or Good Enough? The Effect of ‘Mind-Set’ on Preference Consistency over Time in Tourist Decision Making. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 73, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huifeng, P.; Ha, H. Relationship Dynamics of Review Skepticism Using Latent Growth Curve Modeling in the Hospitality Industry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.Y.; Petrick, J.F. Measuring Attribute-Specific and Overall Satisfaction with Destination Experience. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Kastenholz, E. Corporate Reputation, Satisfaction, Delight, and Loyalty towards Rural Lodging Units in Portugal. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Schwartz, Z.; Gerdes, J.H.; Uysal, M. What can Big Data and Text Analytics Tell Us about Hotel Guest Experience and Satisfaction? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 44, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Customer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, O.; Berezina, K.; Cobanoglu, C. Online Travel Agencies in Hotel Distribution: Game on! J. Hosp. Tour. Cases 2022, 10, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, C.; Huang, C. Online Reviews on Online Travel Agency: Understanding Tourists’ Perceived Attributes of Taipei’s Economic Hotels. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, R. Identification of the Customers’ Preferred Attributes While Selecting an OTA (Online Travel Agency) Platform. Indian J. Mark. 2022, 52, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, N.; Chang, K.; Cheng, Y.; Lai, C. How Service Quality Affects Customer Loyalty in the Travel Agency: The Effects of Customer Satisfaction, Service Recovery, and Perceived Value. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 803–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Liu, M.; Li, W.; Li, L. The impact of Consumer Confusion on the Service Recovery Effect of Online Travel Agency (OTA). Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 24339–24348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Bi, H.; Law, R. Influence of Coupons on Online Travel Reservation Service Recovery. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2014, 21, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Liu, J.; Park, K. The Dynamics in Asymmetric Effects of Multi-Attributes on Customer Satisfaction: Evidence from COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 3497–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavitt, S.; Fazio, R.H. Effects of Attribute Salience on the Consistency between Attitudes and Behavior Predictions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ha, H. Do consumers Really Value All Destination Attributes Equally over Time? The Dynamic Nature of Individual-level Attributes and Their Outcomes. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 2467–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, A.; Johnson, M.D. Determining Attribute Importance in a Service Satisfaction Model. J. Serv. Res. 2004, 7, 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, D.E.; Mangus, S.M.; Folse, J. The Road to Customer Loyalty Paved with Service Customization. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3923–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helson, H. Adaption-Level Theory: An Experimental and Systematic Approach to Behavior; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, L.C.; Ezeh, C. Servicescape and Loyalty Intentions: An Empirical Investigation. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 390–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Hsu, P.; Lan, Y. Cooperation and Competition between Online Travel Agencies and Hotels. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H. The evolution of Brand Personality: An Application of Online Travel Agencies. J. Serv. Mark. 2016, 30, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Rodger, K.; Taplin, R. Moving beyond Visitor Satisfaction to Loyalty in Nature-based Tourism: A Review and Research Agenda. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Pozza, I.D.; Ganesh, J. Revisiting the Satisfaction-Loyalty Relationship: Empirical Generalizations and Directions for Future Research. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrotenboer, D.; Constantinides, E.; Herrando, C.; Vries, S. The Effects of Omni-Channel Retailing on Promotional Strategy. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 360–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swait, J.; Erdem, T. The Effects of Temporal Consistency of Sales Promotions and Availability on Consumer Choice Behavior. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 34, 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, B.; Barnes, B.R. Consumer Perceptions of Monetary and Non-monetary Introductory Promotions for New Products. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 629–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Yoo, J. The Long-term Effects of Sales Promotions on Brand Attitude across Monetary and Non-monetary Promotions. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeybek, Ö.; Ülengin, B. The Effect of Sales Promotions Intensity on Volume and Variability in Category sales of Large Retailers. J. Mark. Anal. 2022, 10, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, N.N.; Vo, L.T.; Ngan, N.T.; Ghi, T.N. The Tendency of Consumers to Use Online Travel Agencies from the Perspective of the Valence Framework: The Role of Openness to Change and Compatibility. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. South Korea’s Tourism Industry: Statistics and Facts. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/4810/travel-and-tourism-industry-in-south-korea/ (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Jeon, D.; Kim, J.; Ko, J. The Impact of Environmental Awareness on Eco-friendly Tourism Attitude and Ecotourism Behavioral Intention in the Post-Corona new Normal. FoodService Ind. J. 2023, 19, 297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Varzakas, I.; Metaxas, T. Pandemic and Economy: An Econometric Analysis Investigating the Impact of COVID-19 on the Global Tourism Market. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araque-Hontangas, N. The Promotion of Spanish Travel Agencies from the 20th Century to the Present. J. Hist. Res. Mark. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ary, D.; Jacobs, L.C.; Razavieh, A. Introduction to Research in Education; Harcourt Brace College Publishers: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- El-Adly, M.I. Modeling the Relationship between Hotel Perceived Value, Satisfaction, and Customer Loyalty. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational Image and Member Identifications. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhan, M. Understanding Factors Influencing Click-through Decision in Mobile OTA Search Engine Systems. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 634–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Shi, X. Web Functionality, Web Content, Information Security, and Online Tourism Service Continuance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.R.; Thongpapanl, N.; Spyropoulou, S. The Connection and Disconnection between E-Commerce Businesses and Their Customers: Exploring the Role of Engagement, Perceived Usefulness, and Perceived Ease-of-Use. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 20, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Huang, T. Exploring Stickiness Intention of B2C Online Shopping Malls: A Perspective from Information Quality. Int. J. Web Inf. Syst. 2018, 14, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanasreh, E.; Moles, R.; Chen, T.F. Evaluation of Methods Used for Estimating Content Validity. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2019, 15, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Sarstedt, M.; Fuchs, C.; Wilczynski, P.; Kaiser, S. Guidelines for Choosing between Multi-item and Single-Item Scales for Construct Measurement: A Predictive Validity Perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S.; Iliescu, D.; Greiff, S. Single Item Measures in Psychological Science. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 38, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.G.; Chen, C.; Jane, T. Improving the Performance of the Unmeasured Latent Method Construct Technique in Common Method Variance Detection and Correction. J. Organ. Behav. 2023, 44, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berliner, R.; Aultman-Hall, L.; Circella, G. Exploring the Self-reported Long-distance Travel Frequency of Millennials and Generation X in California. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W.; Peterson, R.A.; Brown, S.P. Structural Equation Modeling in Marketing: Some Practical Reminders. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2008, 16, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.E.; Swaminathan, S. Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in E-markets: A PLS Path Modeling Approach. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legate, A.E.; Hair, J.E.; Chretien, J.L.; Risher, J.J. PLS-SEM: Prediction-oriented Solutions for HRD Researchers. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2023, 34, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Liengaard, B.D.; Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive Model Assessment and Selection in Composite-Based Modeling Using PLS-SEM: Extensions and Guidelines for Using CVPAR. Eur. J. Mark. 2023, 57, 1662–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liengaard, B.D.; Sharma, P.N.; Hult, G.T.M.; Jensen, M.B.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M. Prediction: Coveted, yet Forsaken? Introducing a Cross-validated Predictive Ability Test in Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Decis. Sci. 2021, 52, 362–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.R. Understanding Priorities for Service Attribute Improvement. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, V.; Ross, W.T.; Baldasare, P.M. The Asymmetric Impact of Negative and Positive Attribute-level Performance on Overall Satisfaction and Repurchase Intentions. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Cheng, S.; Zhou, W.; Song, W.; Yu, S.; Lin, X. Research on the Impact of Online Promotions on Consumer Impulsive Online Shopping Intentions. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2386–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Sivakumaran, B.; Mathew, S. Does Loyalty Matter? Impact of Brand Loyalty and Sales Promotion on Brand Equity. J. Promot. Manag. 2020, 26, 524–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C.; Fajardo, T.M.; Townsend, C. Show It or Say: How Brand Familiarity Influences the Effectiveness of Image-based versus Test-based Logos. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson-Witell, L.; Fundin, A. Dynamics of Service Attributes: A Test of Kano’s Theory of Attractive Quality. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2005, 16, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Liu, T.; Kang, J.H.; Yang, H. Understanding Important Hotel Attributes from the Consumer Perspective over Time. Australas. Mark. J. 2018, 26, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Ha, H. An Empirical Test of the Impact of the Online Review-Review Skepticism Mechanism on Behavioral Intentions: A Time-Lag Interval Approach between Pre- and Post-Visits in the Hospitality Industry. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2070–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zheng, X.; Ling, L.; Yang, C. Online Coopetition between Hotels and Online Travel Agencies: From the Perspective of Cash Back after Stay. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 12, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outer Loading | AVE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T1 | T2 | |

| Satisfaction (CR: T1 = 0.87; T2 = 0.85) | 0.68 | 0.65 | ||

| The vacation booked through the OTA exceeded my expectations. | 0.78 | 0.87 | ||

| My decision to choose this OTA was wise. | 0.84 | 0.74 | ||

| Overall, I am satisfied with my experience with this OTA. | 0.86 | 0.81 | ||

| Loyalty intentions (CR: T1 = 0.90; T2 = 0.91) | 0.75 | 0.76 | ||

| If I get a chance, I will use this OTA again. | 0.87 | 0.88 | ||

| I will revisit this OTA. | 0.89 | 0.87 | ||

| I would recommend this OTA to others. | 0.83 | 0.85 | ||

| Variable | T1: Mean (SD) | T2: Mean (SD) | Alpha T1 (T2) | Mean Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | 4.14 (0.65) | 4.24 (0.57) | 0.78 (0.79) | −0.10 * |

| Loyalty intentions | 4.05 (0.83) | 4.25 (0.72) | 0.82 (0.84) | 0.19 ** |

| Online travel agency selection attributes | ||||

| Security | 4.24 (0.67) | 4.04 (0.66) | −0.20 ** | |

| Information | 4.12 (0.53) | 4.09 (0.50) | −0.03 (ns) | |

| Finding low fares | 4.16 (0.61) | 4.38 (0.53) | 0.16 ** | |

| Ease of use | 3.79 (0.74) | 3.52 (0.62) | −0.27 ** | |

| Post-service quality (price) | 4.09 (0.69) | 4.43 (0.61) | 0.34 ** | |

| Moderator | ||||

| Sales promotions | 3.88 (0.84) | 4.33 (0.62) | 0.45 ** | |

| Fornell and Larcker’s Criterion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| OTA satisfaction (T1) | 0.82 | |||

| OTA loyalty intentions (T1) | 0.23 | 0.86 | ||

| OTA satisfaction (T2) | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.81 | |

| OTA loyalty intentions (T2) | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.62 | 0.87 |

| Heterotrait Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) | ||||

| OTA satisfaction (T1) | ||||

| OTA loyalty intentions (T1) | 0.27 | |||

| OTA satisfaction (T2) | 0.05 | 0.06 | ||

| OTA loyalty intentions (T2) | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.68 | |

| PLS Loss | Indicator Average (IA) | Average Loss Difference | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction (T2) | 1.245 | 1.269 | −0.024 | 0.024 |

| Loyalty intentions (T1) | 1.894 | 1.906 | −0.012 | 0.049 |

| Loyalty intentions (T2) | 1.821 | 1.830 | −0.009 | 0.093 |

| Overall model | 1.653 | 1.668 | −0.015 | 0.005 |

| Attribute | Weight at T1 | Weight at T2 | Difference (Δ) | Significant? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security | 0.16 ** | 0.02 | −0.14 | Yes |

| Information | 0.09 * | 0.08 | −0.01 | No |

| Finding low fares (price) | 0.02 | 0.15 ** | 0.13 | Yes |

| Ease of use | 0.18 ** | 0.02 | −0.16 | Yes |

| Post-service quality | 0.14 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.21 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhi, L.; Ha, H.-Y. Evolving Consumer Preferences: The Role of Attribute Shifts in Online Travel Agency Satisfaction and Loyalty. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2880-2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19040139

Zhi L, Ha H-Y. Evolving Consumer Preferences: The Role of Attribute Shifts in Online Travel Agency Satisfaction and Loyalty. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2024; 19(4):2880-2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19040139

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhi, Luyao, and Hong-Youl Ha. 2024. "Evolving Consumer Preferences: The Role of Attribute Shifts in Online Travel Agency Satisfaction and Loyalty" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 19, no. 4: 2880-2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19040139

APA StyleZhi, L., & Ha, H.-Y. (2024). Evolving Consumer Preferences: The Role of Attribute Shifts in Online Travel Agency Satisfaction and Loyalty. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(4), 2880-2895. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19040139