Abstract

Persona, a special means of image management by social media influencers (SMIs), has become a trending phenomenon and it is expected to substantially affect SMIs’ persuasiveness and ad effect. This study aims to explore the impact of SMIs’ personas constructed through personal values on the effectiveness of social media video ads. Adopting the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework, this study validates how SMIs’ personas constructed through self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values affect consumer cognitive processes and responses. Consumer behavioral intentions are used to verify the effectiveness of ads derived by SMIs. The findings reveal that influencers’ personas constructed by values can promote consumer purchase intention and forwarding intention. Consumer perceptions of self (i.e., ideal self and actual self) have a mediating role. Results also show that SMIs’ personas with self-enhancement values are more effective in stimulating female consumers’ forwarding intention, whereas personas with self-transcendence values are more influential in female consumers’ purchase intention. This study enriches the influencer marketing literature by providing a more tailored understanding of the impact of SMIs’ personas and extending the applicability of value theory. It also provides insights for stakeholders involved in influencer marketing on how to significantly capitalize on the benefits and deploy marketing campaigns.

1. Introduction

In the era of digital marketing, the omnipresence of social media has led to a de facto effect in which users engage in and consume content at a relatively low threshold, providing multidirectional patterns and new dynamics for marketing communications [1]. Contrary to traditional mass media, which is perceived as a distrusted object, social media functions with more specialized, diverse, and fragmented features [2]. Such platforms facilitate the dissemination of news, information, and knowledge. Consumers have become promoters of brands and products and voice their opinions to the masses due to the user-friendly interactive function of social media [3], rather than being passive recipients of marketing efforts. Brands and practitioners recognize the far-reaching impact of social media among consumers, therefore they have integrated social media ads into content and newsfeeds on popular social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and WeChat [4]. According to the statistical data, 78% of consumers regard social media as the top communication medium for connecting them with brands and peers [5], and 90% of users follow at least one brand on social media platforms to keep updated and engaged with brands [6].

Given the widespread use of social media, social media influencers (SMIs) have become a vital touchpoint in fostering beneficial consumer responses. SMIs are contributors that attract a sizable number of followers on networks, possess the capacity to generate valuable content, and present solid reputations in specific regions [7]. Brands continuously forge alliances with SMIs to spread information and promote products, which is a marketing practice known as influencer marketing [1]. Social media platforms empower SMIs to target interests and deliver marketing communications that are superior and customized to specific audiences. Thus, consumers perceive SMIs as a reliable source of advice [8]. Consumers and followers endorse SMIs of their own free will and willingly regard the marketing messages seamlessly presented in SMIs’ posts as credible electronic word of mouth (eWOM) [9]. The reviews and interpretation of information passed on by SMIs and the interaction between SMIs and followers become much more powerful in affecting consumer attitudes, behaviors, and even decision-making processes [10]. This is how the power of SMIs is rooted and can explain why leveraging SMIs’ effect is prioritized by brands and marketers.

The viral potential of influencer marketing blurs the lines between entertaining content and commercial messages, which motivates significant academic and practical interest. SMIs contribute to the significant outreach of marketing information and improve brand value [8], thus, it is vital to launch marketing activities with the right SMIs that can impact the target audience in terms of their choices. What is more, it is noteworthy that SMIs adopt persona construction to manage image, attract and retain followers, create distinct personal brands, and enhance commercial value [11,12]. As suggested by Djafarova and Rushworth [13], an individual may be accepted if his/her image is formed with personalities that are commended and desired by others, particularly in the marketing discipline. The perceived fit between SMIs and consumers reinforces consumers’ intention to accept SMIs’ recommendations [10]. Similarly, Sokolova and Kefi [2] highlight the positive effect of similarities in values between consumers and SMIs on consumer responses. Therefore, SMIs tend to portray positive and pleasing personas that are favored by or are similar to the target consumers. In addition, a persona with values and personalities that align with brand values and product images can enhance the persuasiveness of the ads [14]. Instead, if the SMI’s persona is overly dramatic or unrealistic, it may collapse and undermine followers’ trust. Therefore, an understanding of the influence of SMIs’ personas on consumers and the effectiveness of ads is important to meet academics’ and practitioners’ interests.

In the social media context, the persona is a deliberately presented image of public figures, and essentially, a marketing act. A tailored persona attracts specific follower groups. Persona construction, as a good means of image packaging, contributes to conveying information, meanings, and values. Brands and SMIs have recognized that followers tend to endorse SMIs with positive images [2,13]. They are increasingly embracing positive personas in marketing campaigns to capitalize on the vital potential of personas over consumers. However, there is little discussion underscoring what specific personal values help to construct positive personas. A solid understanding is needed for SMIs to effectively manage and construct their personas and promote themselves to the public. Stakeholders involved in marketing activities can understand how consumers perceive and react to SMIs’ personas that convey specific values and gain insights into the selection of the right SMIs. Despite the increasing attention on persona, the current discussion surrounding SMIs’ personas is mainly focused on theoretical aspects and common sense. Few researchers have empirically investigated the impact of SMIs’ persona construction in the context of social media on how consumers perceive personas and respond to marketing messages.

What is more, the number of online video users in China reached 1.067 billion at the end of 2023. Among them, the number of short video users was 1.053 billion [15], representing the flourished development of social media video-based platforms and video content. Compared to other forms of ads, social media video ads are more effective in persuading consumers because of their vividness [16] and capability to trigger emotions [17]. Social media video ads function as quick attention grabbers [18] that enable SMIs to express and convey their personas more easily and clearly to the public. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on social media video ads.

In response to the research gap and confusion that existed in practice, this study aims to explore what specific values contribute to constructing the positive persona of SMIs and how consumers are influenced and respond to ads. This study intends to provide an understanding of the underlying mechanism of values and SMIs’ persona construction to scholars and persona management for brands, marketers, and SMIs. In light of this purpose, key drivers of successful influencer marketing, including influencer characteristics (i.e., persona constructed by personal values) and consumer psychological variables (self-perceptions), are incorporated into the research model. Accordingly, the current study raised the following research questions:

RQ1: To what extent does the persona constructed by specific values (i.e., self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values) derived by SMIs influence consumer responses to social media video ads?

RQ2: To what extent do consumers’ psychological variables (i.e., ideal self-perceptions and actual self-perceptions) mediate the impact of SMIs’ personas on the effectiveness of social media video ads?

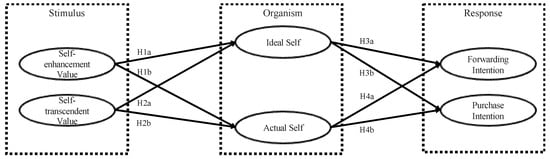

To answer these research questions, this study adopts the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework to explore the consumer cognitive process intervening between SMIs’ personas and consumer responses. This study considers SMIs’ personas constructed through self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values as the stimulus and examines the impact of SMIs’ personas on consumer internal states and final responses. As for the organisms, this paper sheds light on the pivotal role of the consumer’s ideal self-perception and actual self-perception as mediators of the impact of SMIs’ personas on consumer intentions toward short video ads. Affective responses including consumer purchase intention and forwarding intention stimulated by the external stimulus are verified.

This research contributes to the existing literature in three ways. Firstly, through fulfilling the first research question, this study advances prior research on marketing by examining how SMIs’ specific personas (i.e., self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values) affect consumers. Furthermore, as far as we know, we are among the few researchers who explore the mechanism of SMIs’ personas on consumer psychological processes and responses. The validation of the second research question enables us to fill the research gap. Secondly, by considering SMIs as leaders that modify followers’ attitudes and behaviors rather than being solely product endorsers, this study enriches the understanding of the associations between social media marketing and the leadership literature. Thirdly, users’ retweet behavior is an essential topic in communication science. This study regards consumer intention to forward ads as an important metric for measuring ad effectiveness, especially in social media and influencer marketing where sharing is a vital mechanism for information diffusion. By considering consumer forwarding as a beneficial consumer response to SMIs’ social media video ads, this study adds value to the disciplines of marketing, communication science, and image management. In terms of practical contributions, this study provides valuable insights to highlight the significance of SMIs’ personas when brands and marketers cultivate influencer marketing campaigns and provides strategic suggestions on the selection of proper influencers to endorse products and services.

The rest of this study is structured as follows. Section two reviews the research on influencer marketing, image management, and influencer persona, and the extant literature on the effectiveness of social media ads and influencer marketing. The third section elaborates on the theoretical framework and hypothesis development. Section four demonstrates the methodology used in this article (i.e., data collection, questionnaire development, and measurement methods). Section five describes related data and the results of the analysis. The sixth section demonstrates the key findings, the contributions from both theoretical and practical perspectives, and limitations and suggestions for future research. The last section provides a conclusion of this study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Influencer Marketing and SMIs

The prevalence of influencer marketing lies in the rapid development of digital and social media marketing, and the use of SMIs in marketing practice has motivated significant academic attention and resulted in an increasing body of literature. SMIs can be defined as individuals who incorporate digital platforms into persuasion, social interaction, self-presentation, and self-promotion [12,19]. Contrary to traditional celebrities who seek and maintain an accentuated distance from audiences, SMIs and their power are infused with more accessible and trustworthy characteristics [7,13,20] which help to construct SMIs’ identities [21]. SMIs can effectively persuade a diverse group of consumers and alter their attitudes and behaviors by serving as experts in particular regions or on specific topics [22]. Consumers perceive the brand-related and product-related content generated by SMIs as much more authentic and connected than the ads directly passed on by brands [23]. Therefore, SMIs as spokespersons of brands hold initiatives for promotional content to foster consumers’ positive responses.

The extant research on the influencer marketing topic is devoted to exploring a diverse range of influencer attributes, content features, and related advertising outcomes. Table 1 presents a summary of closely related references pertinent to this study. In particular, researchers demonstrate that the endorsers’ characteristics, such as perceived credibility, attractiveness, expertise [2], and popularity [7], will positively affect consumer responses and persuasiveness of marketing information. The underlying mechanisms, such as emotional aspiration and attachment, endorser–brand fit [9], message value and narrative strategies [20], disclosure of sponsorship [24], and consumer desires to follow advice and mimic behaviors [22], are inevitable topics. Consumer outcome variables including brand attitude [4], engagement [10], trust, and purchase intention [23] are used to verify the marketing effects. In addition, the discussion about the influencer effects has primarily focused on the mainstream social networks where textual and picture-based content constitute the main means of interaction and communication, such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook [1,13]. Scholars assert the importance of validating whether consumers would behave and respond differently depending on the type of social media platforms [10]. Given the vividness and sociability of social media video ads [16], they are more impactful marketing tools for triggering consumer emotional responses [17] than other types of ads and other forms of social media content. The joint effect of dynamic visuals and audio enables social media video ads to become more effective in storytelling and more distinct image sharing [18]. The relatively low threshold of content creation also leads to high engagement and bonding, since social media video ads are kinds of user-generated ads where users are mostly in charge of what they would like to upload and desire to see in the videos, especially on social media short video platforms [16]. Therefore, social media video ads with more dynamic features that provide explicit and implicit content in video forms with a higher engagement rate need more academic attention. Since the understanding of the influencer effect in social media video ads is still underdeveloped, this study will investigate the impact of SMIs’ personas derived from social media video ads.

Table 1.

Research focuses and gaps in the key research concerning influencer marketing.

The influential power of SMIs on consumers and ad effectiveness can also be discussed from an opinion leadership perspective. An individual possesses opinion leadership when he/she is perceived as a role model by the public and exhibits great influence on others’ decision-making processes and attitudinal and behavioral responses [28]. According to the two-step flow theory developed by Katz and Lazarsfeld [29], opinion leaders exert a mediating role in the information dissemination between mass media and consumers and affect how consumers react to marketing content. They are effective in motivating consumers with a stronger proclivity to accept SMIs’ advice Casaló [10], positive brand attitudes, and purchase behavior [13]. Researchers investigated the driving force of SMIs’ opinion leadership, including follower size, perceived popularity and likeability [7], interpersonal communication, and electronic word of mouth (eWOM) [8]. SMIs also exert opinion leadership by maintaining proximity with their followers and consumers [22]. The power of opinion leadership is further strengthened by the extent to which information provided by SMIs is considered persuasive and appealing, and the level of perceived fit of personalities and interests between SMIs and consumers [10]. Studies that consider SMIs as opinion leaders elaborate on how content value and strategies, motivations, and capabilities contribute to SMIs’ opinion leadership, and aim to identify the antecedents. However, when SMIs have become leaders over followers, their personalities and traits that spontaneously and continuously alter consumers’ attitudes and perceptions are somewhat overlooked. Therefore, this study will fill this research gap by exploring the impact of SMIs’ personal values as an important aspect of SMIs’ leadership which influences consumer reactions to commercial messages in video ads.

2.2. Image Management and SMIs’ Personas

The SMI’s persona is a pre-set image before presenting and promoting themselves to the public in certain circumstances, which refers to the social media context in this study. Therefore, this section will elaborate on concepts regarding image management and persona to explain current understanding of the SMI’s persona and its effect. As for individual image management, Goffman [30] proposes a well-known framework for managing identity and presenting self. The model indicates that it is human nature to portray a desirable image of oneself and behave in consistence with the pre-determined personas when interacting with others. In this context, it comes as no surprise that products and services with promotional motifs of forming one’s ideal image are pervasive and have a significant resonance among consumers [31]. This explains why SMIs subconsciously or deliberately form and maintain a positive image when engaging with followers. As a special means of self-presentation and image management in the social media context, the concept of persona varies in different circumstances and scenarios. It initially refers to the image setting and theatrical presentation of character costumes and masks [32], and it then evolves into traits and social roles that people wish to construct and exhibit in reality [19]. Individuals can construct their personas in various ways. For example, celebrities consider cultural elements, reputation, status, and sartorial styles when forming their public identity online as a persona to present themselves and maintain their fascination [19]. SMIs tend to incorporate personalities and identities in a better state when constructing personas to establish connections with users and followers [13]. Brands have recognized the value of the ongoing cooperation with SMIs in the long term [20], thus it is necessary to understand the influencer effect from a long-standing perspective, namely the personas constructed by SMIs that can continuously influence consumers.

Most importantly, a favorable persona facilitates shortening the social and psychological distances between the performers and audiences [30], thus it is expected to further enhance endorsement effectiveness on social media platforms. What is more, the image in the marketing discipline refers to the perception and impression of an object held by consumers, which is formed through consumer interpretation [33]. As for methods to manage persona and image in social media, images can be constructed through content with individualized features such as personal meanings, individual identity, personality attributes, and values [8]. SMIs primarily manage images and impressions through eWOM, personal branding, legitimizing expertise, and reputation maintenance [12]. SMIs can also use content tactics to build identities and present themselves, especially through the explicit and implicit narratives posted in textual and visual forms that align with commercial content [21]. This idea is further developed by scholars stating that SMIs exhibit social roles and status, thoughts, and physical identities with associations of symbols, languages, and other practices to frame the overall impression and eWOM [8]. Although practitioners have recognized the importance of SMIs’ personas in persuasion, few experiments measure the related effects and identify the effective approaches to use them for commercial purposes, representing a gap in the influencer marketing literature. What is more, through review of the literature on individual image management, one consensus is that personal traits and values are important to construct an image that makes up the consumers’ overall perception of an object and phenomena. Therefore, this paper will enrich the understanding of this viewpoint by investigating how specific values of SMIs contribute to persona construction as a special means of image management and affect consumers’ perceptions and responses to social media video ads.

2.3. Effectiveness of Social Media Ads and Influencer Marketing

Efforts have been made to advance the knowledge about the advertising effect that SMIs exert from various perspectives. Since the core theme of influencer marketing is to capitalize on the pivotal role of SMIs in the consumer decision-making process, most research and reflection in this vein rest on consumer outcomes. This idea is supported by Vrontis et al. [1] and Peña-García et al. [34], who assert that consumers’ attitudinal and behavioral responses constitute the main approach to investigating the effectiveness of influencer endorsement. In this vein of research, consumers’ approach behaviors that depict consumers’ evaluations and attitudes [35] have been widely adopted as subjective metrics to measure the social media advertising effect; for instance, intention to purchase [26], intention to visit [25], trust [23], and attitude toward brands and products [4]. In addition, since the nature of these subjective indicators such as individuals’ evaluation and perception are somewhat unobservable, scholars routinely use surveys to capture consumer behavior data.

Purchase intention serves as an important component while assessing social media advertising effect; it can be defined as the likelihood that consumers desire ownership and may be inclined to buy a certain brand or product [36]. This notion is further developed by Peña-García et al. [34], who utilized a cross-cultural study to elaborate on the relationship between purchase intention and consumer actual behavior. They confirm that consumer online purchase intention is the powerful precursor of the subsequent online purchase behavior. As such, scholars have widely employed purchase intentions to assess customers’ perceptions of ads, products, and brands [26], and to evaluate social media ad effectiveness [23]. Prior research in this vein indicates that consumers’ intrinsic factors, including perceptions and interpretations, are one of the determinants of the success of social media ads [34,37]. In this sense, consumer psychological processes will have a profound role over the social media video ads effect. Specifically, when consumers are exposed to marketing messages, the perceived meanings attributed to brands and products are determined by their perceptions of self, personal distinctions, and experiences [31]. After that, consumers’ affective responses are triggered, as evidenced by their attitudes and interpretation of the ads and related content, and they will convert into opinions and perceptions toward the endorsed products disseminated by the ads, which will positively affect their purchase intention and the advertising effect [37].

Apart from purchase intention, consumer engagement with brands and influencer campaigns on social media networks serves as a powerful indicator of their attitude and consequent behavioral outcomes [22]. The “share” behavior as part of engagement is regarded as an important marketing metric for ad effect [27,38]. The intention to share, so-called the forwarding intention or repost intention, can be defined as the likelihood of which individuals are willing to share the message related to the marketing campaign within social media networks [39]. Consumers can share their affinity with brands and products by forwarding brand-related content in the forms of photos or texts within their social media networks [38,40]. This is in line with the research of Ajzen [36], which reveals that consumers’ intentions are the key predictors of the degree to which individuals would be willing to engage in specific behavior, and purchase intention acts as the main antecedent of actual purchasing behaviors [34]. To elaborate on the effectiveness of social media video ads, this study uses purchase intention to examine the degree to which consumers will be willing to carry out purchase behavior after viewing the social media video ads and forwarding intention to examine the extent to which consumers would like to forward the social media video ads to others. To sum up, this study proposes that consumers’ perceptions of self, which are triggered by SMIs’ personas, will positively affect consumers’ purchase intentions and intentions to engage with the ads by forwarding ads to others.

3. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

3.1. Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) Model

The research model and hypotheses of this study are proposed based on the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model developed by Mehrabian and Russell [35] and the value theory of charismatic leadership. In the S-O-R model, various external inputs that constitute the stimulus can have an impact on individual internal states including cognitive and affective structures, which then influence the patterns of behaviors that individuals ultimately exhibit [25,41]. In other words, the S-O-R model posits that individuals perceive and react to external changes in a cognitive manner, and emphasizes how crucial individuals’ cognitive, emotional, and affective processing of information are when confronting external changes. Researchers in the marketing context have adopted the S-O-R framework to comprehend how characteristics of advertisements, marketing messages, and product endorsers affect consumers’ internal states and attitudinal as well as behavioral responses [25,42]. This provides evidence for the applicability of the S-O-R model in the marketing region.

As for the components of the S-O-R model, the stimulus consists of various external factors such as environmental and marketing mix inputs that lead to changes in the individuals’ affective or cognitive states [42]. In this study, the stimulus is the SMIs’ characteristics (i.e., the persona constructed by self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values) derived from social media video ads, and they are expected to alter consumers’ affective responses. Organism represents individuals’ cognitive process of psychological activities stimulated by the external stimulus which mediates the relationship between external factors and individuals’ consequent emotional and behavioral responses [35]. In this study, the affective and cognitive facets of organism refer to consumer perceptions of self that are triggered by the SMIs’ characteristics. Response components in the S-O-R framework describe the ultimate consumer outcomes including approach behaviors (i.e., behavioral intention) or actual behaviors directed toward a particular setting [26,35]. This study focuses on the positive approach behaviors elicited by SMIs’ personas, which are purchase intention and forwarding intention. This practice is consistent with the findings that these subjective variables are strong indicators of consumers’ positive final actions [26,35].

In conclusion, the S-O-R framework provides the theoretical lens that external factors (i.e., SMIs’ personas) will impact consumer internal changes (i.e., the perceptions of actual self and ideal self) when they receive marketing information online. This, in turn, is expected to foster consumer positive responses to social media video ads. SMIs serve as charismatic leaders over followers and consumers, and their personal values as a vital component of the overall persona will spontaneously serve as a stimulus when consumers are exposed to social media video ads. Consumer final responses including their purchase intention and forwarding intention are depicted under the S-O-R framework. Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework in this study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

3.2. Personal Values and Charismatic Leadership

A fair amount of the literature has investigated values that individuals employ. According to Spranger [43], individuals develop value systems through the aggregation of inner inclinations, minds, judgments, dislikes or prejudices, and the interaction patterns that affect one’s worldview. Similarly, personal values from various aspects are essential in directing one’s actions and interpreting behaviors exhibited by others, especially for those in leadership manner and roles, for instance, perceptions, personalities, motivations, viewpoints, attitudes, knowledge, and experiences [44]. Researchers claim that values consciously or subconsciously provoke individuals’ attitudes and shape actions within the criteria and value realms [44,45]. When individuals present unique beliefs and personality characteristics incorporating confidence and moral righteousness and serve as role models that cultivate others’ collective behaviors, they are seen as charismatic leaders [46], and personal inclinations are internal forces that shape the leadership styles [47]. Therefore, values that depict personal inclination are inevitable elements when considering the influential power of leaders over their followers. Following this logic, SMIs who use expertise, attractiveness, and the authoritative voice to shape potential consumers’ attitudes and behaviors can be regarded as charismatic leaders in the social media context.

Ample research explores what values need to be considered while examining charismatic leadership and how values in differing motivational scenarios affect behaviors. Schwartz [48] conceptualizes the values of charismatic leaders into two dimensions which are self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values. Individuals with self-enhancement values have strong desires for personal interests and tend to pursue gains, power, and achievement, while individuals with self-transcendence values exhibit the pursuit of collective benefits and altruistic concerns for others [45,48]. Bearden et al. [49] illustrate the interpersonal influence of values on consumers and state that consumers are eager to be accepted by the reference groups and prevent social exclusion by complying with the values of leaders. Research by Bagozzi and Dholakia [50] reveals that opinion leaders convey values and norms and convince consumers to embrace these characteristics to cultivate consumers’ similar consumption behaviors with the reference groups. Similarly, consumers’ acceptance of SMIs’ values and norms and desires to imitate their behaviors trigger consumers’ interest in the products and services recommended by SMIs [21]. Since consumers tend to present desires for the ownership of products recommended by SMIs [8], this study proposes that SMIs as charismatic leaders have the influential power to persuade consumers to buy the endorsed brands and products.

Prior studies advanced that values could affect consumers’ reactions to products and marketing messages. In particular, authors have observed that SMIs involve the values of brands and products in content creation to improve their potential to convince consumers to purchase [20]. SMIs are recognized as online opinion leaders because of their personality characteristics such as expertise, authenticity, and potential power over followers [22]. However, few works have been undertaken on SMIs from the perspective of charismatic leaders [10]. In addition, the existing studies consider values and personalities in general terms, and they fail to elaborate on how specific the personal values of SMIs exert influence in the information diffusion process. Therefore, a more in-depth understanding of this viewpoint is needed. In line with the statement that the influence of opinion leadership exerted by SMIs on followers’ behavioral intentions is related to engagement [22], we adopt the S-O-R model and value theory of charismatic leadership to form the underlying framework. In this study, we posited that the SMIs’ personas, constructed by personal values (i.e., self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values) and presented in the social media video ads, would act as the antecedent to consumers’ psychological process (i.e., ideal self-perception and actual self-perception) and in turn influence their behavioral intentions (i.e., purchase intention and forwarding intention), which are as follows:

H1.

SMIs’ personas constructed by self-enhancement values will have a positive effect on consumer (H1a) ideal self-perceptions and (H1b) actual self-perceptions.

H2.

SMIs’ personas constructed by self-transcendence values will have a positive effect on consumer (H2a) ideal self-perceptions and (H2b) actual self-perceptions.

3.3. The Mediating Role of Consumer Self-Perceptions

Researchers extend attention to how consumer psychological factors and other endogenous features alter their behaviors and attitudes. As suggested by Sirgy [51], consumers expect consumption experiences that inspire them, trigger their self-identities, and enrich their senses, rather than focusing on brands or products alone. This notion is also supported by Casaló et al. [10], who assert that consumers prefer to embrace influence and opinions from sources that they are similar to or identify with, whereas they tend to reject viewpoints from which they wish to dissociate. In the same vein, Thompson and Hirschman [31] carried out a study to examine the relationship between consumers’ sense of self-image, self-perceptions, and consumption motivations from a poststructuralist perspective. They claim that consumer decisions toward brands and products are dependent on consumers’ self-perceptions, as consumers have motivations for products that satisfy their needs to control and improve self-image and convey the ‘self’ that they wish society would accept. These ideas bring academic attention to consumer self-concept.

The self-concept that depicts consumer behaviors is defined as individuals’ cognitive and affective evaluation of themselves and can categorized into actual self-perceptions and ideal self-perceptions [52]. The actual self refers to one’s perceived reality and highlights who and how the individual views himself/herself, while the ideal self is formed by the ideal vision, imagination, expectations, and goals related to who and what the individuals aspire to become or believe they would be [14,52]. Consumers tend to purchase brands and products with personalities and values that are similar to either consumer’s actual self or ideal self [13,22,51]. The homophily between the consumer’s self-perceptions and brand image creates consumption value [10]. As a result, consumer self-perceptions are crucial in ad persuasion and have become a major topic in marketing in recent years.

In line with the findings that consumers’ choice of brands and products are actions through which consumers construct their identities and convey symbolic and social meanings [14,31], these choices are influenced by either the actual self-congruence or ideal self-congruence. In particular, brands, products, and services are assumed to have personality images [53]. Consumers can achieve actual self-congruence by perceiving a match between the personalities of brands and products and consumers’ actual self-perceptions [51]. Following this reasoning, consumers, brands, and products are ideally self-congruent when the personalities of brands and products can reflect what consumers desire or believe to become [14,52].

In addition, scholars consider the homophily between endorsers’ characteristics and consumer self-perceptions, and the effect on consumer outcomes. According to Choi and Rifon [54], the ideal self-congruity between endorsers’ perceived image and consumers’ ideal self-perceptions can enhance endorsement effectiveness. This opinion is extended by Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández [22] from traditional advertising into the context of social media. They demonstrate that under the role of SMIs, the perceived fit between brand and consumers’ self-perceptions increases the expected values and consequently reinforces their behavioral intention toward brands. In the same vein, Rabbanee et al. [27] suggest a positive effect of self-congruity in terms of brands’ personalities and consumer self-perceptions, which further motivate consumers to engage with brand-related content on social networks. To sum up, the self-congruity between personality characteristics of endorsers, brands as well as products, and consumers’ self-perceptions is effective in cultivating positive consumer responses, such as engagement, emotional attachment, positive attitude, and purchase intentions.

Since self-congruence can foster positive consumer attitudinal and behavioral responses to marketing information and brands [14,52], researchers demonstrate that consumer self-perceptions are crucial for emotional attachment to occur among stakeholders (i.e., brands, endorsers, and consumers). Consumer self-perceptions are expected to play a prominent role in enhancing the effectiveness of social media video ads and thereby should be involved in the design of influencer marketing campaigns. Furthermore, consistent with findings that influencers’ characteristics will exhibit positive effects on consumers’ attitudes and behaviors [23], we suggest that consumer self-perceptions will have a mediating role in the relationship between SMIs’ personas and subsequent consumer intentions.

Based on the above-mentioned considerations, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H3.

SMIs’ personas constructed by values will have a positive effect on consumer ideal self-perceptions, which will in turn positively influence consumer responses, including (H3a) consumer forwarding intentions and (H3b) consumer purchase intentions.

H4.

SMIs’ personas constructed by values will have a positive effect on consumer actual self-perceptions, which will in turn positively influence consumer responses, including (H4a) consumer forwarding intentions and (H4b) consumer purchase intentions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection

In the current study, the experimental data were obtained by scenario-based online questionnaires. The online sample service was provided by Wenjuanxing, a professional questionnaire data collection platform in China. This platform has been adopted by many enterprises, universities, and researchers. A total of 504 questionnaires were distributed to users of social media video websites through the Wenjuanxing platform, of which 445 samples were valid. The survey was conducted from October 2023 to December 2023. The effective response rate of the questionnaire was 88.29%.

4.2. Measurement Items

This study aims to investigate the roles of SMIs’ personas constructed via self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values. Thus, the questionnaire was designed with two scenarios in which the effect of SMIs’ personas with two types of personal values were measured separately. We made a declaration at the beginning of the questionnaire to participants as follows: “This questionnaire is conducted anonymously, and all the data collected in this questionnaire is for academic research only”. After that, participants had access to general information about scenarios and the formal questions of the questionnaires. The data for the effect of SMIs’ self-enhancement values were captured in Scenario 1, whereas the effect of self-transcendence value was collected in Scenario 2. In each scenario, participants were initially required to read general information about the shopping scenario and the SMI’s persona conveyed by corresponding values. Specifically, the SMI in the questionnaire was described as a well-known expert in his/her active field and has professional certifications in both scenarios. The difference is that in Scenario 1, SMIs usually demonstrate products in person and provide professional evaluations according to the characteristics of products that align with the needs of the audience. The SMI’s status and recognition in the field attracted many fans. In contrast, in Scenario 2, the SMIs usually participate in public welfare activities and actively pay attention to and speak up for the disadvantaged. The SMI’s kind and positive image attracted many fans. Next, the content highlighted a persona that was pre-set and conveyed in social media video ads. After that, participants proceeded to answer the questionnaire by rating their perceptions and selecting the items that best matched themselves based on the scenario. All questions in the questionnaire were compulsory for participants to finish them.

Scales and items in this questionnaire regarding consumer purchase intention, forwarding intention, the SMIs’ personal values, and consumer self-perceptions were designed according to the previous research. Specifically, the first part of each scenario was constituted by items of purchase intention adopted from Sokolova and Kefi [2] and followed by forwarding intention adopted from Rabbanee et al. [27] and Lee and Ma [38]. Items of self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values were self-developed according to the previous studies conducted by researchers like Schwartz [48]. Consumer perceptions of the ideal self and the actual self were adopted from Malär et al. [14] and Sirgy et al. [51]. The last part of the questionnaire was constituted by demographic questions. The Likert five-point scale was used to measure to what extent participants perceived the persona of the influencer, to what extent their self-perceptions worked, and to what degree participants rated their corresponding intentions (1 = Strongly deny, 5 = Strongly favor). The measurement items are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Measurement for variables.

4.3. Features and Measurement Models

In consistency with studies on the topic of influencer marketing, this study adopted SPSS 29.0 and AMOS 26.0 for data analysis purposes. A set of 24 features were modeled to help understand the impact of SMIs’ personas constructed by personal values on consumers’ responses and were categorized into the following dimensions including purchase intention (PI), forward intention (FI), self-enhancement value (SEV), self-transcendence value (STV), ideal self (IS), and actual self (AS). These features and hypotheses were subsequently analyzed through the two-step approach of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) [55]. What is more, the measurement model assessment involves the estimate of reliability and validity, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Followed by the second stage of the SEM model and bootstrap analysis to examine the path relationships among the constructs, an independent samples t-test was conducted.

4.4. Sample Description

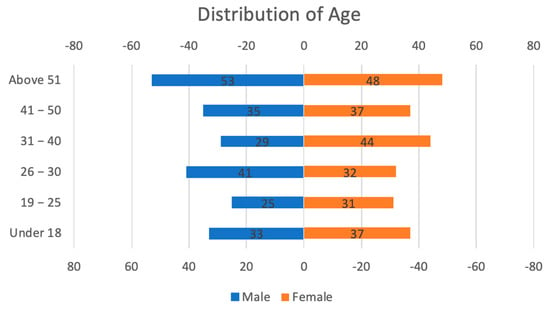

As presented in Table 3, out of the 504 questionnaires distributed, 445 participants completed the questionnaire and their responses are valid. There were no significant differences in the demographic variables. Of the respondents, 48.54% were male and 51.46% were female. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of age. Specifically, the largest group of respondents were more than 50 years old (22.70%) while the smallest group was for respondents who were between the ages of 19–25 (12.58%). The majority of respondents had a good educational level, of which 28.09% had a college degree, 22.92% had a bachelor’s degree, and 25.62% had a master’s or higher degree. The exchange rate to convert a Chinese yuan to a US dollar was 1 CNY = 0.140031 USD, employed on 19 August 2024. Of the respondents, 19.55% were found to have an actual monthly income between CNY 3001 and CNY 6000 (USD 420 to USD 840), and 16.63% of respondents had an actual monthly income level between CNY 10,001 and CNY 15,000 (USD 1401 to USD 2101).

Table 3.

Demographics of respondents (N = 445).

Figure 2.

Distribution of age.

5. Results

5.1. Structural Equation Modeling

5.1.1. Reliability

The SEM model helps simultaneously examine various interrelated relationships between variables, including the observed variables (i.e., indicators) and non-observed variables (i.e., latent constructs) [55]. Thus, this study used the two-stage SEM method to validate the theoretical framework and research hypotheses. In the first step of the SEM model, there was a need to assess the construct reliability and validity of the scales and items of the measurement model [56].

Before testing the structural model, Cronbach’s alpha was employed to test reliability. According to Nunnally [57], the recommended level for coefficient alpha is 0.70. As for the results, the highest value of Cronbach’s alpha (0.891) was for SMIs’ self-transcendence value followed by SMIs’ self-enhancement value with a value of 0.880 while the lowest Cronbach’s alpha (0.800) was for consumer forwarding intention. Cronbach’s alpha for ideal self-perceptions and actual self-perceptions were 0.806 and 0.802, respectively. All constructs had an adequate level of internal consistency reliability as the values of Cronbach’s alpha exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70.

5.1.2. Validity

Factor analyses such as an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were performed to check whether items were loaded on the proposed and original constructs and examined the validity of the measurement model. Before the factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Barlett’s tests were performed to assess the adequacy of the statistics and suitability for factor analysis [58]. As for the results, the value for KMO was 0.898, which was higher than 0.6 as suggested by Pett et al. [58]. Also, the results of Barlett’s test ( = 2624.094, df = 66, p < 0.001) revealed that the statistical data were suitable for factor analysis and that variables were interrelated.

Scales and items of the values, which SMIs incorporate to construct the personas, are self-developed based on Schwartz’s value theory [48] rather than the existing and valid scales that scholars widely use. Thus, the EFA was used to assess whether a total of 12 items in these two constructs were loaded on the proposed constructs. Specifically, values of the minimum factor loading of items under SEV and STV were 0.674 and 0.683, respectively. The factor loading for all items exceeded the value of 0.6 as recommended by Nunnally [57], which indicated that all items of the proposed scales were loaded on the respective latent constructs. What is more, values of the minimum communality of items under SEV and STV were 0.574 and 0.569, respectively, revealing that the results of communality of all the items were higher than 0.4. In addition, the rate of cumulative variation explained by these two constructs was 63.751%, exceeding the recommended threshold of 60%. By running the principal component analysis (PCA), two constructs (i.e., SEV and STV) were identified in which items were loaded correctly. To sum up, the results indicated that the constructs of persona values were unidimensional. The information of the items and constructs could be effectively extracted to reflect the original data.

The rest of the items in the constructs of purchase intention, forwarding intention, and consumer perceptions of ideal self as well as actual self were designed in line with the scales in previous research, thus CFA was performed to verify the convergent and discriminant validities. Under CFA, factor loading, significant level, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) were computed to assess the convergent validity [56], and the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) was used for measuring the discriminant validity [59]. The summarized results in Table 4 represent that loading values for all items were higher than 0.6; each item was loaded correctly and significantly on the respective construct. The scores for CR of all constructs were above 0.7, and the figures of AVE were greater than 0.5 according to the recommended level suggested by Hair et al. [56]. To test the discriminant validity, Fornell and Larker [59] suggest that values for the square root of AVE of each construct should exceed the shared correlations with other constructs. The conditions were satisfied for all constructs and variables (see Table 4). These results reveal that all of the constructs were unidimensional, as well as the measurement.

Table 4.

The CFA results.

5.1.3. Model Fit for the Measurement Model

Several indices were considered to examine the goodness-of-fit of the measurement model, such as chi-square (), chi-square/degrees of freedom (/DF), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). As shown in Table 5, the fit indices of the measurement model for both scenarios were found to be within the cut-off criteria suggested by Gerbing and Anderson [55], Hu and Bengler [60], and Bollen [61]. This demonstrates that the measurement model was an adequately good fit with the observed data. In sum, the construct reliability, validity, and model goodness-of-fit of the measurement model were assessed at the first step of the SEM, and all conditions were satisfied. Thus, the second step of SEM analysis, which is the structural model, were proceeded to validate the relationships among the variables and test the research hypotheses.

Table 5.

Fit indices of the measurement model.

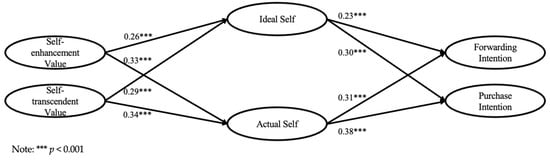

5.1.4. Validation of Structural Model

In the second step of SEM, associations between the latent constructs and research hypotheses were examined by the structural model analysis [55]. This study used AMOS 26.0 to test the proposed hypotheses. The goodness-of-fit statistics indicated that the structural model had a significantly poorer fit with the data ( = 406.978; df = 243; /df = 1.675; p < 0.001; GFI = 0.929; RMSEA = 0.039; AGFI = 0.912; CFI = 0.967; NFI = 0.921; TLI = 0.962) according to the standards of goodness [55,60,61]. Further, Figure 3 and Table 6 present the path analysis results of the hypothesized model. These results demonstrated that all of the path coefficients were statistically significant and in the predicted directions, which supported the proposed model. Specifically, it can be seen from the corresponding coefficients and significant level in Table 6 that SEV ( = 0.26; p *** < 0.001) was significantly related to the ideal self-perceptions. Another path from SEV ( = 0.33; p *** < 0.001) to the actual self-perception was also recorded to be significant. H1 advanced that SMIs’ self-enhancement values as the means of persona construction would positively affect consumer perceptions of ideal self (H1a) and actual self (H1b), thereby H1a and H1b were supported. Likewise, STV was significantly related to ideal self-perceptions ( = 0.29; p *** < 0.001) and actual self-perceptions ( = 0.34; p *** < 0.001); this supported that SMIs’ personas constructed by self-transcendence values positively affect consumers’ (H2a) ideal self-perceptions and (H2b) actual self-perceptions. Concerning the effects of consumer self-perceptions triggered by SMIs’ values on consumer behavioral intentions, the ideal self-perception was significantly related to forwarding intention ( = 0.23; p *** < 0.001) and purchase intention ( = 0.30; p *** < 0.001). This empirical evidence validated H3a and H3b which predicted the positive relationship between the ideal self-perceptions and forwarding intention (H3a) and purchase intention (H3b). The relationship between the actual self-perceptions and forwarding intention was positive and highly significant ( = 0.31; p *** < 0.001), therefore, H4a was supported. Moreover, the actual self-perception was found to have the largest value of coefficient with purchase intention ( = 0.38; p *** < 0.001), which supported H4b. To sum up, since the p values for all constructs were significant at 0.001 level, SMIs’ self-enhancement value and self-transcendence value, consumer ideal self-perception and actual self-perception can significantly explain the corresponding latent variables, and all of the related paths are valid, by which the hypotheses were supported.

Figure 3.

Validation of the structural model.

Table 6.

Results of unstandardized estimates of the structural model.

5.2. Bootstrap Analysis

The mediating role of consumer self-perceptions on the relationship between SMIs’ personas constructed by values and consumer intentions was also confirmed by the bootstrap method. SPSS 29.0 with Process 3.3 was used here. Contrary to the judgment criteria of other analyses that consider the significant level (p-value), the mediation effect computed by the bootstrap analysis is determined by whether the interval (i.e., BootLLCI, BootULCI) contains 0. In the case that 0 is not included in the interval, the mediating effect is significant. As presented in Table 7, the values of BootLLCI and BootULCI of the indirect effect of all proposed paths exceeded zero, which means that the mediating effects of consumer ideal self-perceptions and actual self-perceptions were significant in the relationship between SMIs’ personal values and consumer intentions. Additionally, in each hypothesized path, the values of the indirect effect of the mediator on the corresponding dependent variable were lower than the figures of the total effect, which indicates that the mediating effects exist.

Table 7.

Results for bootstrap Analysis.

5.3. Independent Samples T-Test

The independent sample t-test helps to validate whether there is a difference between a qualitative variable and other quantitative variables [62]. This current study employed an independent samples t-test to assess the difference in genders between values and behavioral intentions. Analysis results in Table 8 present the gender differences in each dimension by using the independent samples t-test. It can be seen that the significant level of forwarding intention was 0.027 in Scenario 1, which was lower than 0.05. This indicated that when social media influencers conveyed a persona with self-enhancement values, the forwarding intentions of female consumers were slightly higher than that of men (M_male = 3.07, M_female = 3.28, p < 0.05). No statistically significant differences were found for the other constructs from the gender perspective in Scenario 1 (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Results of independent samples t-test results.

In the same sense, when social media influencers conveyed a persona with self-transcendence values in Scenario 2, the significance level of consumer purchase intention (0.022) was below 0.05. This indicates that there are differences in the purchase intention of consumers of different genders, as the purchase intention of female consumers is slightly higher than that of men (M_male = 2.67, M_female = 2.89, p < 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences for the other dimensions in Scenario 2. More discussions regarding the results of this study are further presented in the forthcoming section.

6. Discussion

6.1. Key Findings

Despite the substantial body of literature on the influencer marketing topic, solid understanding and adequate empirical research from new perspectives are still needed [10,23]. Since SMIs serve as a vital element of marketing communication and a valuable source of advice for consumers [1,2], it is important to adopt valid and reliable results regarding influencer characteristics, consumer internal processes of information-processing, perception, and responses in the context of social media marketing [22]. In particular, SMIs’ personas have merged as noticeable characters of the SMIs, which is believed to affect their persuasiveness [13], and they have evolved into a trending topic in practice. In order to better capitalize on the influencer effect, practitioners need to understand how a SMI’s persona is constructed and how it works. However, there has been a lack of validation regarding the patterns for constructing SMIs’ personas and their potential impact on the effectiveness of social media ads, which is a critical issue that needs to be solved. As researchers primarily focus on the personality and meanings conveyed by SMIs that are consistent with brands’ and products’ images, and that with consumers [10,14], these implicit characteristics are validated in general and collective terms. To this end, we capitalized on SMIs’ persona construction in the social media context and investigated the impact and underlying mechanisms of SMIs’ personas constructed through specific values on consumer responses to social media video ads. The analysis results revealed that SMIs’ personas conveyed in social media video ads, consumer self-perceptions, and consumer behavioral intentions were interrelated, thereby supporting the conceptual framework.

Specifically, we employed the S-O-R framework developed by Mehrabian and Russell [35] and explained the associations of the above-mentioned variables in a theoretical model, thereby adding insights to the knowledge related to SMIs’ personas. This research regards SMIs as charismatic leaders who exhibit unique personal values and personalities to alter the attitudes and consequent actions of followers and consumers. We propose that SMIs manage their overall image, namely persona construction in the social media context, through employing distinct values that convey different motivations, desires, and personal pursuits. As we hypothesized, findings derived from this study confirm that SMIs’ personas constructed by self-enhancement values as well as self-transcendence values and consumer self-perceptions can positively impact the effectiveness of social media video ads. Furthermore, this study verifies the mediating roles of consumer ideal self-perceptions and actual self-perceptions on the relationship between influencer persona and consumer responses.

In detail, this study contributes substantially to the influencer marketing discipline. Firstly, results derived from Scenario 1 support the hypothesis predicted that SMIs’ personas constructed by self-enhancement values as SMIs’ characteristics will positively affect consumer (H1a) ideal self-perceptions and (H1b) actual self-perceptions. Results drawn from Scenario 2 confirm that SMIs’ perceived self-transcendence values as their persona construction were effective in triggering consumer perceptions. Thereby, the hypothesis proposing the positive effect of SMIs’ self-transcendence values on consumer (H2a) ideal self-perceptions and (H2b) actual self-perceptions was validated. The findings support the significant impact of values on constructing the personas of SMIs when they serve as charismatic leaders to consumers, which aligns with prior studies [46,50]. These results are in line with the findings of Malär et al. [14] which illustrate that the process of individual self-perceptions is dynamic in that ideal self-perceptions and actual self-perceptions can be activated at once when consumers are exposed to external stimuli, and these self-perceptions are generally in concert. The extant research on SMIs and social media marketing campaigns has analyzed variables related to the personalities of influencers, brands as well as products, and concepts of self-perceptions. For example, Casaló et al. [10] demonstrated that the homophily between consumer perceptions of self and brand image cultivates beneficial consumer outcomes. Consumers prefer brands and products that they believe reflect and fit their ideal and actual selves in terms of personalities and values [13,22,51]. However, to the best of our knowledge, these studies fail to explore the construction of the persona through personal values by considering SMIs as charismatic leaders from an empirical perspective. This research verifies the positive and significant relationship between SMIs’ personas formed by values and consumer self-perceptions, thereby providing an advance in the literature on SMIs and influencer marketing.

In addition, results from both scenarios support the hypothesis suggesting that consumer ideal self-perceptions motivated by SMIs’ values positively affect consumer forwarding intention (H3a) and purchase intention (H3b). The findings add evidence to the study by Choi and Rifon [54], who claimed that the ideal self-congruity between influencer image and consumer self-perceptions is a key driver of persuasiveness. In addition, Rabbanee et al. [27] delved into the relationship between self-congruity and social networking behaviors and indicated that the congruity of ideal self-perceptions may drive pro-brand behaviors on social media platforms. Likewise, data collected from both scenarios suggest that SMIs’ values can trigger consumer actual self-perceptions, which in turn positively influence consumer approach behavior. The hypothesis proposing the positive effect on consumer forwarding intention (H4a) and purchase intention of products endorsed by SMIs in social media video ads (H4b) was supported. These findings supported the applicability of consumer self-perceptions in the context of influencer marketing and leadership and are in congruence with recent works [10,22,23]. Further, the present paper validates that consumer self-perceptions can increase consumer forward intention, which is an important marketing metric of engagement. This is consistent with the research by Jiménez-Castillo and Sánchez-Fernández [22], which highlights the positive relationship between consumer perceptions of self and engagement. The results and the above-mentioned discussions provide insights into the second research question concerning the mediating effect of consumers’ psychological variables on the relationship between SMIs’ personas and the effectiveness of social media video ads.

Moreover, the findings derived from the independent samples t-test demonstrate that the effect of SMIs’ personas constructed through different values is greater among females than males in both scenarios. Results from Scenario 1 indicated that female consumers present higher forwarding intention when a SMI’s persona is associated with self-enhancement values and more purchase intention when a SMI’s persona is constructed by self-transcendence values in Scenario 2. This provides empirical evidence to the study by Djafarova and Rushworth [13], which states that SMIs’ features are more influential on female consumers. In addition, personas constructed by self-transcendence values are more influential in female consumers’ purchase intention. These findings provide detailed explanations for our first research question concerning how, and to what extent, SMIs’ personas constructed by different values lead to different consumer responses to social media video ads. The results also provide valuable insights for brands and products at different stages of development. When brands are at different stages of development, their business objectives and consumer communication strategies are different. For newly established brands and products, raising awareness and improving outreach of brands and products are their primary objectives. Hence, when they face consumers and markets for the first time, they can collaborate with SMIs who convey self-enhancement values to encourage consumer engagement and forward the related information on social media platforms. In contrast, for mature brands and products, stable sales volume and market share are their focus. Therefore, they can collaborate with SMIs who present self-transcendence values to trigger consumer purchase intention. Overall, the findings are indicative of the fact that social media influencers’ whose personas are constructed by self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values play a key role in promoting consumer purchase intention and forwarding intention, and the current study contributes to the existing literature on influencer marketing.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

The current research provides important theoretical implications to the existing literature across several dimensions. First, despite the great efforts that have been carried out on the topic of influencer campaigns, the understanding of the influencer effect in the social media context is still underdeveloped. To the best of our knowledge, there are few that employ empirical validations to verify the impact of SMIs’ persona construction, which adds value to the existing research on SMIs. In contrast to the past work that considered SMIs’ values and personalities as a general term [10], this study considers SMIs as charismatic leaders and focuses on SMIs’ personas constructed by specific values (i.e., self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values). Although the existing research pays significant attention to the congruity of actual and ideal self-perceptions between consumers, brands, products, and endorsers in terms of personalities and images, and the corresponding impact on ad effect [13,14,22,51], there is a lack of understanding on how and what specific values of SMIs’ characteristics as a means of image management affect consumer responses to ads. This study extends this line of theoretical argument by offering empirical evidence that a SMI’s persona with values influences self-perceptions (i.e., the ideal self and the actual self), which in turn positively affects consumer approach outcomes (i.e., forwarding intention and purchase intention) toward social media video ads.

Second, the current research provides theoretical extensions to the associations intervening between social media marketing and the leadership literature. SMIs are usually solely considered as opinion leaders, and the corresponding influential power of SMIs on consumers and ads is primarily discussed from an opinion leadership perspective [8,22]. However, Casaló et al. [10] claim that work on SMIs from the perspective of leaders is still needed. According to House [46], charismatic leaders are individuals who project beliefs and characteristics with confidence and morals and can shape followers’ behaviors. This presents similarities to the fact that SMIs use narratives regarding experiences, opinions, appeal, and expertise to attract and influence followers. By considering SMIs as charismatic leaders in the social media context, findings imply that the influence of distinct values exerted by SMIs, as persona constructed by charismatic leaders, is critical in triggering positive affective connections to the recommended products. Thereby, this study adds value by providing an understanding of the influencer effect on consumers in terms of characteristics from a new theoretical perspective and broadens the boundaries of the application of leadership theory.

Finally, this study contributes to the existing research by using consumer forwarding intentions as important indicators to measure the impact of SMIs’ personas on social media ad effectiveness. This addition also helps deepen comprehension of the factors (i.e., one’s characteristics and image as well as impression management) influencing consumer intentions to engage with and spread marketing information within the context of communication science. Since information diffusion is essential for the success of social media marketing companies, this study sheds light on how a SMI’s persona with personal values affects consumer intentions to spread the ads, which is a crucial for marketing information outreach. Given that the current discussion of SMIs’ personas is primarily theoretical [2], the related insights including the empirical evidence hold relevance to influencer marketing, video advertising, leadership, and communication science, in particular, and contribute to the literature.

6.3. Practical Contributions

Our findings provide useful insights for brands seeking to collaborate with influencers to conduct precision marketing among target consumers and niche markets on social media platforms. From a practical perspective, this paper holds implications for the ever-growing influencer marketing industry and social media video advertising industry. The results serve as a foundation for brands and practitioners to make informed decisions in terms of identifying proper SMIs. By shedding light on how brands and marketers can better capitalize on the SMI effect and implement more effective influencer campaigns on social media video-based platforms, many stakeholders can benefit from our practical implications, such as brands, executives, market and data analysts, agencies, and planning teams. SMIs can also benefit from the findings as this study provides evidence for using specific values to construct positive personas that will be recognized by consumers. In particular, our findings offer brands and marketers more in-depth understanding of SMIs’ characteristics and the antecedents of consumer beneficial outcomes. This paper suggests that brands and marketers should pay additional attention to SMIs’ images and the explicit characteristics of SMIs. Beyond solely focusing on characteristics such as the popularity, attractiveness, and the expertise of SMIs, it is important to identify SMIs’ personas constructed by specific values that meet the desires of consumers and are capable of eliciting greater behavioral responses.

Given that anthropomorphic personality serves as a crucial element for brand and product positioning [14,22], and the role of SMIs will impact how consumers perceive and respond to brand-related information [22], we provide solid insights to understand the effect of SMIs’ persona construction on consumers’ psychological processes, which eventually affects consumer attitudinal and behavioral responses. We suggest that marketers prioritize the effect of SMIs’ personas when seeking SMIs for brand and product advocates and cooperate with SMIs’ personas that are cultivated by personal values consistent with personalities appreciated by the target consumers. What is more, the results demonstrate the differences in consumer responses when consumers of different genders are exposed to video ads, and provide insights into designing marketing strategies for the intended consumers. By taking these actions, practitioners can successfully develop their influencer marketing strategies, achieve more expected objectives, and enhance the effectiveness of social media video ads through influencer campaigns.

6.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Although this study sheds light on the pivotal role of SMIs’ personas on consumer intentions and social media video ads, we faced several limitations. First, to verify the impact of the SMIs’ personas, we used online questionnaires and focused on subjective variables including consumer perceptions, purchase intention, and forwarding intention. Although consumer intentions are a strong predictor of their final behaviors, researchers suggest that consumer actual behaviors, such as purchase and repurchase [10], are key indicators while examining ad effectiveness. The experimental approach in this study confronted an issue of external validity [63] and may be less capable in providing more useful insights on the impact of SMIs’ personas derived from SMIs. Therefore, future studies may adopt experiments that integrate objective measures and capture consumer behavioral data to better understand the influence of SMIs’ personas on the consumers and relevant ads.

The second limitation was that this study formed simulated scenarios in which fictitious SMIs endorsed the products through texts. Using fictitious endorsers in questionnaires to form the simulated scenarios may be less effective in fully examining the impact of SMIs’ personas on consumer decision-making and real responses. Fictitious influencers may lack the ability to possess the persona and other personal characteristics of real SMIs who actively engage with followers on social media platforms. For example, fictitious influencers fail to consistently interact with their followers. Therefore, consumers’ perceptions and responses to the fictitious SMIs’ personas were subjected to participants’ differences and imaginations, which may be different from the actual perceptions in real cases. Hence, future studies may present influencers’ persona more intuitively through experiments (i.e., via pictures and videos) to capture consumer perceptions more accurately.

Thirdly, despite the extant research on influencer marketing, image management, and leadership that provided the theoretical basis for this research, more work could be performed to better understand how SMIs can construct their personas and the related effects. SMIs usually manage their images and construct personas in various ways in real cases. However, this research considered the limited scenarios in which SMIs construct their personas solely by their personal values. Future studies may explore more scenarios and relevant variables to provide insights into SMIs’ persona constructions, such as SMIs’ identities, signs, symbolic labels, and even the collapse of a persona. We also encourage researchers to take a step further to compare the mechanisms of these different elements regarding SMIs’ persona construction and investigate the long-term beneficial or hampering effects on consumers and social media video ads.

Finally, we suggest that brands and marketers select SMIs with personas that are consistent with the brands’ and products’ images that they intend to promote, and the values as well as personalities that are highly appreciated by the intended target consumers, considering the benefits in enhancing consumer trust in the commercial information on social media platforms.

7. Conclusions

The pivotal role of social media influencers on consumer outcomes and advertising effects has attracted substantial attention from scholars and practitioners. Influencers’ activity forms favorable images to retain attractiveness and interact with consumers. This growing phenomenon imposes the need for understanding how influencers can form their images and affect consumers in complex marketing practices. Despite the extant literature on influencer marketing focusing on the mechanism of influencer effects on consumers and ads, to the best of our knowledge, we are of the few researchers to empirically investigate the effects of social media influencers’ personas as a means of image management. We proposed a theoretical framework to measure the impact of social media influencers’ personas constructed by specific personal values on the effectiveness of social media video ads. This framework provided useful insights from a new perspective on influencer marketing by considering social media influencers as charismatic leaders, which was different from previous research that mainly regarded influencers as product endorsers. We empirically demonstrated that social media influencers’ personas constructed by self-enhancement values and self-transcendence values positively affect the effectiveness of social media video ads in terms of consumer purchase intention and forwarding intention. We also explored the mediating role of consumer psychological variables (i.e., ideal self-perception and actual self-perception) on the relationship between influencers’ personas and consumer responses to social media video ads. The effect of an influencer’s persona on consumers of different genders was also confirmed. These findings enriched the connection between influencer marketing and the leadership literature and provided more insights into understanding the determinants of successful influencer marketing, which offers significant value for scholars and in real-life practice. However, the present study was limited by the fact that the focal outcome was consumer purchase intention drawn from simulated scenarios in which influencers solely form their personas via distinct values. Given that influencer marketing is still an emerging research topic, future studies can further replicate this study and improve it by incorporating consumer actual behaviors captured in real-world shopping and experimental situations where influencers present various personas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and J.R.; methodology, H.C.; validation, H.C.; formal analysis, H.C.; data curation, H.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.; writing—review and editing, H.C. and J.R.; visualization, H.C.; supervision, J.R.; funding acquisition, J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Grants No.: RKX20231110090859012, JCYJ20220531095216037), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant No.: HIT.OCEF.2024047), and Guangdong Provincial Self-Specialized Fund Upper Level Project (Grant No.: 2023A1515012520).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vrontis, D.; Makrides, A.; Christofi, M.; Thrassou, A. Social media influencer marketing: A systematic review, integrative framework and future research agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 617–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberton, C.; Stephen, A.T. A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: Research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 146–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Bansal, S.; Kandpal, C.; Aswani, R.; Dwivedi, Y. Measuring social media influencer index-insights from Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]