Abstract

Word of mouth (WOM) is crucial in customers’ purchasing decisions and affects companies’ long-term profits. This study examines the long-term trends in companies’ dynamic pricing and profits by using the Hamiltonian function method and dynamic simulation to construct a dynamic equation. It takes into account the intensity of word of mouth faced by companies and analyzes the level of publicity and consumers’ predictions of product quality. In this paper, we also discuss the interactive processes between WOM and advertising levels, the two most prominent market factors, and their ultimate impact on companies. The experimental results show that elevated levels of external advertising can potentially prompt companies to establish higher product pricing strategies, particularly in scenarios where the intensity of word of mouth is pronounced. In the initial phases of market development, the saturation level of consumers within the market exerts a negligible influence on companies’ long-term profit margins. Conversely, the rate of natural attrition from consumers’ upper threshold of product quality expectations distinctly impacts companies’ profitability.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of the internet and the enhancement of its dissemination capabilities have significantly increased the scope and influence of word of mouth (WOM) [1,2]. In particular, with the advent of Web 2.0 and new media channels, as well as the development of various social media platforms such as forums, online shopping reviews, and microblogging sites, word of mouth has established a broad foundation [3,4,5]. Increasingly, consumers are using various online platforms to share and exchange information about products and services [6,7]. The literature and empirical evidence confirm that 97% of customers are influenced by consumer opinions [8] and 93% of customers rely on online reviews to make their purchase decisions [9]. The spontaneous word-of-mouth behavior of consumer groups is known as WOM [10]. WOM significantly impacts the shaping and altering of consumer buying desires as well as company market decisions [11,12]. For instance, Toyota has developed the Toyota Friend platform to realize WOM among consumers. Through a private social networking service for Toyota owners, they can interact with their cars, dealers, and Toyota. Additionally, they can connect to open social networks such as Facebook or Twitter and use this tool to communicate with their friends and family. Consequently, Toyota leveraged the dissemination of WOM to reach more potential consumers. Similarly, CicirCity and Amazon allow customers to read and leave product reviews on their websites, facilitating WOM [2].

WOM is an extended form of expression based on the network externality effect, which is an intermediary for spontaneously spreading the influence of goods or services within consumer groups [13]. Consumers’ access to or sharing of information about any company, product, or brand name through online social media platforms strongly influences their purchase decisions [14,15]. The dissemination of WOM in the market primarily stems from the gap between consumers’ expectations of a product and its actual performance, which may lead to surprise or disappointment among those who have purchased a product [16,17]. This positive or negative evaluation spontaneously spreads among consumer groups, influencing potential consumers in the market who have not yet purchased the product and subsequently affecting the future profit levels of companies [18,19]. Under the influence of WOM, companies’ long-term pricing and profits will exhibit diverse trends, as product pricing, in most cases, directly determines consumer expectations regarding product quality. Therefore, how WOM influences companies’ pricing strategies and promotes them to achieve high profits has become a noteworthy business issue.

As the user base gradually expands, spontaneous WOM increasingly influences consumers’ assessments of products [20,21]. Prior to making online purchases, customers value online information to assess the suitability and limitations of online shopping [22]. Generally, spontaneous WOM within consumer groups has both positive and negative impacts [17,23,24]. Positive WOM generally stems from the high quality, unique design, and excellent after-sales service of a company’s products, leading consumers to provide favorable evaluations after trial use or purchase. Additionally, these consumers are likely to become loyal customers, attracting new ones to the business [8]. Therefore, companies engage in WOM promotion on their websites or related social media channels to establish a positive corporate image [25]. Negative WOM is also common in practical economic societies and activities. Consumers’ perceptions of low-quality products and corresponding services often lead to negative evaluations, resulting in a reluctance to purchase these products [26]. Simultaneously, potential consumers in the market will abandon their purchase intentions due to negative WOM about the product, gradually leading to the loss of customer groups and ultimately rendering a company unprofitable [27]. Hence, companies with poor WOM must constantly strive to change customers’ perceptions of their products and services [28,29]. Since WOM is long-lasting, companies dynamically adjust their product pricing based on market conditions to capitalize on positive WOM about their products and meet consumers’ expectations of product value, thereby maximizing long-run profit levels [30]. Organizations such as Amazon and Harrah’s have significantly boosted their profits by leveraging the consumer data they have collected [31,32]. Hence, conducting research on companies’ long-term dynamic pricing strategies within the WOM framework facilitates analyzing pricing strategies and profit levels, thereby providing valuable recommendations for their sustainable development.

With the rapid development of social media, WOM has emerged as a novel form of product promotion, complementing traditional advertising methods and ultimately convincing more potential consumers in the market to purchase a company’s products [33,34]. However, WOM is characterized by its temporality, meaning that it does not generate immediate returns for businesses in the short term. Instead, its impact becomes more evident after accumulating over a longer period. In the market environment jointly shaped by companies and consumers, while companies engage in fixed advertising activities, WOM among consumers has a comprehensive influence on long-term pricing and profits [35,36]. Therefore, effectively leveraging WOM is crucial for the long-term development of companies.

In markets where WOM is prominent, consumers who have purchased a product perceive its true quality and influence potential consumers’ valuation of the product through evaluations, experience sharing, and other forms of person-to-person communication. Therefore, this study analyzes the impact of WOM within consumer groups on company pricing and profits from the perspective of consumer evaluations and shopping-experience sharing in the context of online platform development. Additionally, more companies are willing to attract consumers by establishing communication channels for their products to obtain consumer feedback and adjust product pricing appropriately at different times. Consequently, this study dynamically considers the entire process, investigating the impact of WOM on consumer valuation, company pricing, and profits to provide suggestions and predictions for the long-term development planning of companies.

In summary, this study focuses on how to maximize the utilization of WOM’s spontaneous dissemination characteristics within consumer groups to continuously adjust product pricing levels over the long term. This satisfies the majority of consumers’ valuation of the product and achieves long-term profit maximization. The study considers a dynamically changing system of the impact of WOM within consumer groups on companies’ long-term profits and product pricing. It constructs a dynamic state transition equation and establishes a market system composed of a single company and consumer groups. Additionally, consumers’ valuation of product quality will continuously change over time under the influence of WOM. By studying the different trends of the impact of various parameter changes on company long-term profits and pricing, this study uses the Hamiltonian algorithm and dynamic numerical simulation software to investigate the equilibrium evolution path of companies’ long-term pricing and profits.

2. Literature Review

Word of mouth significantly impacts consumers’ purchase intentions and companies’ marketing strategies. Therefore, this study conducts a literature review on the fundamental influence of word of mouth on consumers and companies. Additionally, considering that word of mouth typically persists in a normal market environment, consumers’ assessments of products and companies’ pricing decisions are not static over the long term. Hence, a comprehensive review of the impact of word of mouth in the context of dynamic evolution is presented.

2.1. Research on Influence of Word of Mouth

2.1.1. Research on Influence of Word of Mouth on Consumer Groups

WOM influences consumer behavior in various ways, such as advertising, social media, content quality, and quantity. Dodson et al. (1978) [37] established a consumer diffusion model in the market based on the impact of WOM, arguing that the number of different types of consumers constantly changes under the influence of WOM, affecting the interaction among consumers (both purchasers and nonpurchasers). Hennig-Thurau et al. (2015) [26] studied the impact of WOM on consumers’ product purchase behavior through empirical research and experiments on the Twitter effect. Kim et al. (2017) [38] examined the guiding role of externalities from advertising and WOM in consumer purchasing behavior, using the film and video industry as an example for modeling and explanation. Qi and Kuik (2022) [33] adopted an exploratory approach to investigate the interactive relationship between electronic WOM (eWOM) on social media and offline WOM, as well as its impact on Chinese consumers’ decision-making process for purchasing remanufactured products. The study revealed that offline WOM moderates the influence of social media and eWOM on purchase decisions. Hyun et al. (2020) [39] investigated WOM on the retail of Chinese consumer electronics products in the US market. The study revealed that WOM marketing can increase consumer trust but can also reduce it through health awareness and price consciousness, ultimately affecting consumer loyalty. Jagaty and Dash (2023) [2] examined the impact of the quality and quantity of eWOM content, as well as the sender’s expertise, on purchase intentions. The study revealed that the level of interest in products and brand perception regulate the link between product WOM management and purchase intentions. Zhang et al. (2022) [6] constructed a model of the impact of an artificial intelligence WOM system on consumer purchase behavior, dividing WOM systems into four aspects: professionalism, information quality, information volume, and information intensity. The study found that consumers are most concerned with information quality and intensity in purchase behavior analysis.

Scholars often use the content of online reviews to characterize WOM and investigate its impact on consumer behavior. Tata et al. (2020) [40] employed social influence theory and the concept of negative bias to investigate the impact of online reviews and the sources of online reviews on customer attitudes and purchase decisions in both public and private consumption contexts. Xu (2020) [41] used text mining and empirical research methods to investigate whether customer online reviews truly reflect customer overall satisfaction with hotels. The study revealed that not all positive (or negative) textual factors extracted from online customer reviews significantly influence overall customer satisfaction. The actual impact of WOM on customers can vary depending on different psychological changes. Craciun et al. (2019) [42] expanded existing research on online product reviews, focusing on the impact of WOM among different gender groups, providing insights for various decision makers and strengthening corresponding management reviews. Li et al. (2022) [43] extracted and analyzed evaluations of online dating services by using three machine learning algorithms to analyze sentiment and the impact of online WOM on people’s opinions and decision making. Li and Zhang et al. (2023) [44] provided a dynamic product evaluation model from the perspective of potential customers, simulating the cognitive process of potential consumers processing customer reviews based on six hotels’ online reviews.

Attention has also been given to WOM’s positive and negative effects on consumer behavior. Keeling et al. (2013) [45] discussed the impact of employee WOM from the perspective of internal recruitment, considering staff WOM (SWOM) as a specific form of WOM. They studied the influence of positive and negative information received by employees on their motivation and encouragement, explaining the impact of positive and negative WOM on potential customers from the perspective of information acquisition. Han et al. (2020) [18] empirically examined the relationship between customer satisfaction and review motivation in online review platforms. The study showed that the intention of customers to post online hotel reviews varies depending on their level of satisfaction. In most cases, online reviewers are more eager to post extreme and negative reviews, thereby influencing consumer behavior.

2.1.2. Research on Influence of WOM on Corporate Decision-Making Behavior

WOM primarily influences corporate decision-making behaviors through advertising, product quality, and service quality. Tapiero (1983) [46] considered consumer behavior and consumer responses to corporate advertising, proposing a stochastic diffusion model of WOM that primarily evaluated company advertising policies. Zhen et al. (2019) [47] studied the impact of WOM on consumers’ purchase behavior during the initial market launch of new products, focusing on profit choices under different corporate strategies, and discussed the influence of WOM and advertising costs on corporate decision making. Blodgett et al. (1993) [48] considered consumer complaint behavior and argued that such behavior actually leads to negative WOM. They studied the extent of service provision by companies under such behavior, pointing out that the cost for companies to maintain current customer satisfaction is far lower than that of attracting new customers. Therefore, companies should implement successful strategies to stabilize consumers. Godes (2017) [49] focused on the relationship between WOM and product quality, finding that WOM ultimately influences people’s assessment of the utility provided by products they are familiar with. Additionally, WOM promotion among consumer groups can reduce the advertising level of companies to a certain extent, but the magnitude of the changes is not consistent. Wang et al. (2019) [50] considered tWOM among consumers and the uncertainty of demand and studied the optimal strategy for software suppliers to release software. The study concluded that the skip strategy is the best choice when net WOM is negative and sufficiently small. However, when net WOM is negative but not small enough, the replacement strategy becomes optimal. When net WOM is positive, the line extension strategy outperforms the other two strategies. However, regardless of whether the quality design is externally given or optimized, the overall advantages of the three release strategies are similar. Çavdar, B. and Erkip (2023) [51] studied the interaction between operational decisions and shipping policies in the demand for electronic retailer systems. Customer preferences were modeled based on the perceived service quality provided by WOM. This information was then integrated into the operational issues of retailers to determine shipping policies, including consolidated shipping times and regular demand processing. Electronic retailers can announce longer delivery times for regular customers in markets with low competition. However, the influence of WOM may reduce profits.

Some scholars have focused on online reviews as the main content of WOM, studying its impact on corporate behavior. Li et al. (2019) [52] analyzed the impact of online reviews on corporate business. Textual reviews left by consumers on the internet significantly affect corporate sales performance through the role of eWOM. Similarly, Berger et al. (2020) [53] studied how marketers use textual data such as online reviews and marketing communications to obtain the greatest benefits. They explored the mechanisms of how textual data under the influence of WOM affect relevant audiences and discussed how researchers can address internal and external validity issues. By considering WOM, the study combined marketing with text analysis. Li et al. (2020) [34] noted that user-generated content (UGC) reduces customer-perceived risks and consolidates online store sales, further illustrating the fundamental impact of WOM on corporate decision making. Electronic retailers can develop economic UGC marketing strategies by improving key UGC factors. Anagnostopoulou et al. (2019) [54] also noted that WOM from positive online reviews, contrary to negative reviews, exhibits greater homogeneity and consensus. The online reputation resulting from WOM will be an important indicator affecting corporate financial performance. Based on attribution theory, Song and Duan (2022) [55] attributed eWOM dispersion to the comments of consumers and fake reviewers. Employing the context experimental method, they introduced eWOM dispersion as an independent variable and explored the impact mechanism of eWOM dispersion on consumer order decisions under different personal characteristics. The study revealed that eWOM dispersion has a negative impact on order decisions, which can be moderated by the influence of attribution choices. Feng and Zhang (2019) [56] established a theoretical model to test the optimal pricing strategy of sellers when considering online WOM information. In the absence of consumer reviews or WOM, the optimal price should decrease over time. Among consumer reviews, the impact of online WOM on pricing depends on consumer characteristics, such as mismatch costs, and product characteristics, such as product quality.

The above studies show that scholars currently focus primarily on the impact of WOM on company performance in the market. In most of the literature, the research method considers online reviews as representative manifestations of WOM. For most studies, empirical research is the most commonly adopted research form.

2.2. Research on Influence of Word of Mouth on Company Strategy under Dynamic Conditions

WOM in the market is often related to its duration; hence, the study of WOM under dynamic conditions has garnered significant attention from scholars in recent years. Many scholars have examined WOM from various dimensions based on dynamic conditions.

Early research focused on advertising as a crucial factor and investigated the impact of WOM under dynamic conditions on corporate profit and cost-related decisions. Monahan (1984) [57] proposed a stochastic and dynamic advertising model that integrates advertising and WOM, exploring how companies choose advertising expenditure rates to maximize long-term expected profits. Archer et al. (1994) [58] developed a dynamic cost model describing service demand’s evolution from its initial state to long-term equilibrium. This model encompassed factors such as WOM and advertising, arguing that advertising can facilitate transitions between consumer states of unawareness, positive perception, and negative awareness, thereby influencing service demand. This study explored the long-term impact of service levels on customer groups and analyzed decisions related to the timing and cost of providing extensive services. Caulkins et al. (2011) [59] also established dynamic system equations to investigate the impact of optimal pricing and advertising levels on companies’ profits when market potential changes. The article analyzed the post-purchase utility of consumers, demonstrating the influence of advertising levels. Bruce et al. (2012) [60] constructed a dynamic linear model to investigate the dynamic impact of advertising and WOM on heterogeneous product demand across different stages. The research study indicates that it is more effective for companies to increase advertising spending in the early stages due to repeated wear and tear and synergies with WOM. However, in the later stages, increased WOM activities may drive demand.

More recently, scholars have examined the impact of WOM under dynamic conditions on corporate pricing and profit-related decisions in multiple dimensions, such as price, reviews, and quality. Ouardighi et al. (2016) [30] noted that the impact of WOM on corporate profitability depends not only on the level of advertising investment but also on the comparison between corporate pricing and consumers’ reservation prices for products. Dynamic pricing decisions influenced by advertising and WOM and the interactive processes among different customer groups were studied. Chevalier et al. (2006) [28] studied the impact of consumer reviews on online book sales (Amazon and Barnesandnoble.com) from a dynamic perspective. More positive reviews lead to a gradual increase in book sales, thereby increasing online book sales revenue. Anand et al. (2011) [61] used queuing theory to investigate the relationship between service time and quality changes. They found that the quality of service provided to consumers is related to the speed of service delivery, and this relationship between quality and speed can influence consumers’ preferences for services. This provides guidance for dynamic research on the spread of WOM in service delivery. Caulkins et al. (2011) [62] considered the impact of brand image during economic downturns and studied long-term pricing policies for companies. When the price of a product is high enough, it distinguishes itself from other products; however, if the product is discounted, a brand image is established. Furthermore, Ajorlou et al. (2018) [63] chose the smartphone application market as an example to study the optimal dynamic pricing problem of monopolistic companies considering WOM propagation among consumers in social networks. It developed a dynamic pricing model and found that although prices frequently drop to near zero, the optimal price trajectory does not become stuck near zero. Li et al. (2018) [64] established a dynamic model based on positive and negative WOM reviews to analyze the overall profit of WOM marketing. The impact of different factors on the expected overall profit of WOM marketing activities was explored. Feng et al. (2019) [56] developed a theoretical model to test sellers’ optimal dynamic pricing strategy when considering online WOM information. In the absence of consumer reviews or WOM, the optimal price should decrease over time. Among consumer reviews, the impact of online WOM on pricing depends on consumer characteristics and product characteristics, such as mismatch costs and product quality. This article pays more attention to short-term and dynamic corporate strategies to respond to changes in WOM. Dou et al. (2021) [65] used the brand-level customer survey data provided by the BAV group, developed a model in which customer capital depends on key talents’ contribution and brand recognition, and analyzed the implications of brand recognition on the valuation and risk of firms. They further developed a dynamic model to analyze how firms’ corporate decisions were affected by customers’ brand recognition. Belo et al. (2022) [66] used the firm-level data estimation structure model of American companies to decompose the enterprise value, showing that the brand capital accounts for 6–25%. They found that the contribution of brand capital to the enterprise value decreases with the increase in the average labor skill level of the industry.

Delre and Luffarelli (2023) [67] studied the temporal dynamics between eWOM and box office sales during a film’s lifecycle by establishing a three-stage least squares regression model. They found that previous eWOM valence positively impacts current eWOM valence and remains constant throughout a film’s lifecycle. In contrast, the positive impact of previous eWOM volume on current eWOM volume decays rapidly.

The above studies show that research on the dynamic performance of WOM in the long term is still somewhat insufficient. Most studies research consumers, consider the impact of the existence of WOM on market demand in the long term, and pay less attention to the relevant decision-making behaviors of companies. Subsequent research in this study will comprehensively consider WOM in the long term with respect to corporate advertising, pricing, and other factors. The comparison between this study and the main reference studies is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of this study and main reference studies.

Among the extensive research literature on WOM, there is still a relative scarcity of studies using modeling methods to investigate the impact of WOM on company pricing and profits under dynamic conditions. Most of the literature employs empirical research methods and approaches to explore the influence of WOM in a specific local market, such as the works by Tapiero C.S. (1983) [46], Keeling K. (2013) [45], and Tata (2020) [40]. Furthermore, several model-based studies concentrate solely on the immediate effects of WOM on companies or consumers within the current phase, disregarding a crucial aspect of WOM, namely, temporal persistence. This was exemplified by Wang Y., Li M. (2019) [50], and Feng and Zhang (2019) [56]. Therefore, this study employs a dynamic modeling approach to delineate the long-term impact of WOM on companies, thereby exploring optimal decision-making behaviors for companies in the long run.

3. Problem Description and Basic Assumptions

From a dynamic research perspective, this study explores the impact of word of mouth on consumers’ valuation of products and companies’ pricing strategies, with a focus on analyzing the changes in long-term profits for companies. The fundamental assumption underlying this study is that a single company exists in the market, producing products of a certain quality level at a given production cost. Consumers estimate the quality level of a product before purchasing it. After purchasing and trying the product, they provide positive or negative reviews based on the actual and perceived quality discrepancy. This generates positive or negative WOM among consumer groups. The market also maintains a certain level of advertising, and consumers will only choose to purchase the product if they believe it will provide positive utility. Given the persistent nature of WOM, companies dynamically adjust their product pricing to promote consumer purchases.

The mathematical symbols and parameter variables used in the modeling process are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Relevant parameter settings and explanations.

To maintain generality and scientific rigor, we assume that consumers have heterogeneous estimates of the quality of products sold by enterprises. This estimation has an upper limit , which varies due to several factors in the market. For instance, companies’ existing advertising efforts in the market may influence consumers’ maximum estimations, and WOM present in the market also significantly affects this upper estimation limit.

First, the external advertising level of enterprises can influence the maximum estimation of consumers in the market, but WOM among consumers may have an either positive or negative impact. The quality of the products ultimately produced by enterprises is fixed, but it may not necessarily be higher or lower than consumers’ estimations. Additionally, it is assumed that the greater the external advertising efforts of enterprises are, the greater the basic estimation of consumers. However, the model assumes that the only decision variable for enterprises is price , and they do not make decisions regarding the advertising level. This is because WOM makes enterprises more willing to let products be spontaneously promoted and disseminated among consumer groups. Therefore, companies will invest in advertising based on the external advertising level in the market, such as the advertising extent of similar enterprises in different markets. In addition, they will not continuously vary their advertising level decisions over the long term. However, enterprises that advertise incur costs. Since there is a clear correlation between WOM and time, the model is characterized by using a dynamic system equation as follows:

The first section indicates the impact of advertising on the estimated upper limit, while the second section reflects the influence of WOM. When , , and vice versa, , which implies a twofold effect of consumer purchases D at each moment in time on the estimated upper bound . The quality of products produced by companies is an exogenous variable subject to technological or cost constraints, and the quality of products can only reach a certain level, such as in 3D printing. The third section demonstrates the natural decay of consumers’ highest estimation of the product over time. In other words, if a company refrains from any actions in the market, consumers may perceive that the product’s technological, and research and development attributes will gradually fail to meet their own or market demands, thus presenting natural attrition.

Notably, in the model presented in this chapter, advertising efforts made by companies and WOM in the market only affect the upper limit of consumers’ estimation of product quality, without influencing the lower limit. This implies that consumers’ estimation of product quality will conform to the range of , where the upper limit of estimation may experience some fluctuations, while the lower limit of 0 remains unchanged. This is based on two assumptions and aligns with reality. First, companies increasingly focus on potential target customers in the market. They tailor their advertising to different consumer preferences to enhance consumers’ attention to their products and boost sales. For instance, Sina Corporation leverages user registration information and cookies to assess consumer behavior and preferences, enabling targeted advertising to its intended audience. However, when faced with indifferent consumers, Sina reduces its advertising efforts. This approach ensures that indifferent consumers’ interest in Sina’s products does not increase, and their valuation of the products remains unchanged. Conversely, for enthusiastic consumers, such advertising efforts enable them to learn more about the products from advertisements, subsequently altering their valuation based on this information.

On the other hand, the primary focus of this chapter is WOM, which, to some extent, originates from online advertisements and promotions and is particularly evident on the internet. Consequently, consumers who initially have a low valuation of a product are less inclined to spend time browsing through numerous promotional advertisements. Therefore, advertising efforts by companies do not affect the lower limit of consumers’ product valuation in the market, only the upper limit. Both reasons suggest that consumers’ estimation of product quality fluctuates within a range of , with only the upper limit varying over time.

Assuming that consumers’ own predictions of product quality , . Since only consumers who have purchased the product are able to generate word of mouth, it is assumed that consumers will purchase it when . That is, the valuation interval of consumers who will buy is . is computed as follows:

As a result, the company is maximizing profit, and the profit maximization function is

in which , , and .

4. Model Analysis

To visualize the monotonicity of the control variables with respect to the other parameters, the Hamiltonian operator for the companies’ profit maximization function is constructed:

Above, is the costate variable.

The Lagrangian function is constructed according to the Hamiltonian operator:

First, a simplification of the Hamiltonian function gives

Thus, the Lagrangian function can be further expressed as

Therefore, the first partial derivative of the Lagrangian function with respect to pricing is

Proposition 1 provides a description of the pricing extremum condition.

Proposition 1.

Companies are exogenous to the level of advertising in the case of decision-only pricing levels, and the Lagrangian function pricing extremum condition is .

Based on the conclusion of Proposition 1, some preliminary monotonicity conclusions regarding pricing extremum conditions can be obtained. First, it can be observed that pricing increases as the level of company advertising improves. Increasing advertising levels is the most direct approach for companies to attract more potential customers in the market. Advertising elevates the upper limit of consumers’ estimations of product quality on the market while also altering the willingness to purchase among other consumers through WOM. When advertising intensity is high, consumers are highly likely to possess quality estimations exceeding the actual quality of the product. However, lower advertising levels may result in consumers underestimating the product’s true quality. These two different scenarios can lead to WOM among consumers that appears to affect in different directions. Simultaneously, increased advertising levels imply higher advertising costs, necessitating companies to increase product pricing to offset these costs. Second, pricing also increases with , the quality of the product. Enhanced product quality signifies greater costs incurred during production, and higher pricing can compensate for these costs. Finally, the formula reveals that WOM significantly influences long-term decision making, particularly when advertising levels are high. Higher advertising levels combined with WOM in the market encourage more consumers to purchase the product. However, if companies set high prices and consumers discover a discrepancy in actual quality, WOM in the market can significantly impact long-term profits, prompting companies to slightly lower their pricing.

After obtaining the initial monotonicity conclusions on pricing extrema, to solve the dynamic system and the companies’ profit maximization function, it is necessary to consider the state equation of the costate variables. For the costate variables, the relevant calculation formulas yield

By substituting and solving for the Hamiltonian function, a simplification is performed to obtain

As a result, the model can be solved based on the equations for both the upper limit of consumer quality prediction and the costate variable over time.

Depending on the model setup, the initial and end states of the system equations should be specified. The maximum estimate of consumers must be greater than 0 and does not eventually converge to 0 over time. Therefore, it is assumed that can be used as an initial end condition for the system. Since there is an unconstrained in the terminal state of the system at , the covariate condition is used to complement this, i.e., .

This dynamic system is nonlinear, and it is impossible to find the optimal dynamic variation in the control variable and the state variable with respect to time t; therefore, the next step is to use the numerical solution method to solve it.

First, based on the extreme pricing value condition obtained from Proposition 1, we substitute it into

The relevant conclusion of Proposition 2 can be obtained.

Proposition 2.

In this nonlinear system, the final expressions for the upper bound of the consumer’s mass estimate (the state variable) and costate variable with respect to time change are

Above, , and .

In this chapter, we have derived the upper limit of consumers’ quality estimation, denoted by , and the relationship between the costate variable and the control variable . As the initial conditions for the costate variable at t = 0 is unobtainable, an estimation method is employed to find the values that satisfy the terminal condition of the costate variable being 0. In the subsequent sections, we will elaborate and analyze the impact of various parameters.

5. Numerical Experiments

MATLAB was used to solve the dynamic system equations in this study. First, appropriate values for the costate variables were sought. Subsequently, based on the upper limit of consumers’ estimation and the values of the costate variables, the evolution of companies’ profits in the long run was studied. Furthermore, to clarify the impact of WOM and other parameters on the dynamic system, adjustments to the relevant parameter values were made in subsequent numerical experiments.

5.1. Influence of Word of Mouth

Based on the model analysis, the external variables are assigned according to the actual situation of firms and the existing literature [59,62].

Let ; then, the parameter values are put into the differential equations for numerical simulation. The formulas for the values of the equations are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The formulas for the influence of WOM on price and profit.

The ode45 function is used to analyze the price and profit of the equilibrium state. When , the costate variable can converge to 0 at the end of the system. At this time, the sensitivity analysis of the influence strength of the WOM effect is carried out. .

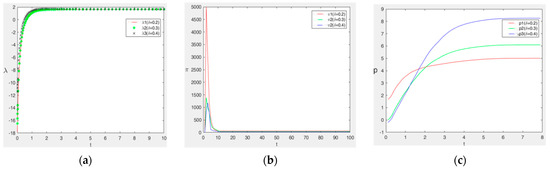

In order to make the research results more obvious, the parameters representing the strength of the WOM effect were tested several times. The influence strength of the WOM effect on the evolutionary paths of , profit, and company pricing are shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

The influence of on the WOM effect: (a) the influence of on symbiotic variable ; (b) the influence of on profit; (c) the influence of on company pricing .

The profits that can be obtained by enterprises gradually increase over time, while the pricing gradually decreases over time in Figure 1. Such a phenomenon is reasonable, because the consumer’s initial estimate of the quality of the product is only slightly higher than the actual quality of the product. This difference in quality will lead consumers to believe that the purchased product is worth the money, thus spreading positive WOM in the market. It not only promotes the purchase possibility of future consumers but also increases the valuation ceiling. When the valuation ceiling continues to rise, consumers gradually find that the real quality of the product cannot meet the very high quality expectations, and this gap makes negative WOM begin to play a more powerful role. In this case, in order to maintain the sales of goods, enterprises will choose to reduce the price of products to influence more consumers’ purchase decisions.

When consumers within the market are more proactive or rely more heavily on WOM to disseminate product attributes, other consumers’ purchase decisions are more significantly influenced. This implies that a higher intensity of WOM in the market will amplify the impact of both positive and negative consumer evaluations towards a product, further leading companies to adopt different pricing control strategies. To investigate the impact of WOM on company profits, this chapter adjusts the influence parameters of WOM in numerical experiments while keeping other parameters constant, studying the changes in the evolution path of profits.

Compared with the setup , when and , the equilibrium pricing level of the company has slightly decreased at this point, along with a certain reduction in profit levels. This indicates that the increase in WOM makes consumers pay close attention to the usage evaluations shared by other consumers. If the company continues to adopt higher pricing levels, most consumers will perceive the product as not worthy, resulting in negative WOM and significantly reducing the company’s profits.

Proposition 3.

As the intensity of the influence of WOM among consumer groups on profits first increases and then decreases, a higher level of advertising gradually reduces company profits and ultimately stabilizes at a lower level.

According to Proposition 3, the pricing level of enterprises changes with the change in the WOM effect, the initial valuation ceiling, and other factors. As the intensity of WOM among consumers continues to increase, the company’s profit level in the long run ultimately stabilizes at a gradually decreasing level. First, because there is a variable upper limit on consumers’ estimations of product quality on the market, the indifference of consumers in choosing to purchase a product is also influenced by the company’s pricing level. The increasing intensity of WOM makes consumers more sensitive to perceived differences in product quality. At the same time, the company’s pricing level for the product causes most consumers to estimate that the quality of the product exceeds its actual quality. Therefore, the upper limit of consumers’ estimations rapidly decreases due to the presence of WOM, resulting in a gradual decrease in the company’s ultimate profits. This is also the main reason why company profits decline faster as WOM increases, as shown in the figure.

From the perspective of the advertising level, although enterprises do not make dynamic decisions on the advertising level, the initial advertising investment also affects consumers’ initial estimation of product quality. This is also reflected in the representation of the point of no difference in utility (aq > p). With the increase in the intensity of WOM, a company’s profits undergo a trend of initial increase followed by a decrease in the early stages, as shown by the groups of numerical experiments in Figure 1. This is because under the current circumstances, the company’s advertising level for the product is relatively high, leading to a high probability that consumers estimate the product’s true quality as greater than its actual quality. In such a scenario, the company recognizes that as the number of consumers purchasing the product increases, the negative impact on profits due to WOM also becomes stronger, especially when the intensity of WOM is high. Therefore, the company chooses to increase pricing to reduce the number of purchases at the current time t, thereby mitigating the negative impact caused by WOM. Under these conditions, consumers who choose to purchase a product are those who have a higher estimation of product quality. Consequently, these consumers are willing to pay a higher price for the product, increasing the company’s profits during the early stages of evolution. However, as time progresses and WOM spreads, the company’s pricing increases, further reducing market demand. When the negative effect of reduced demand outweighs the positive effect brought by high-valuation consumers, the company experiences a decline in profits. This explains the evolutionary path of profits shown in the figure, where profits initially increase and then decrease. This conclusion is generally consistent with the findings of Caulkins et al. (2017) [59].

Based on the above three sets of numerical experiments, the existence of WOM has a significant impact on corporate profits. In addition, strong WOM can even alter the trend of profit changes. Consequently, WOM in the market indirectly influences a company’s behavior in advertising, pricing, and other areas and maximizes its profits. Furthermore, through the analysis of the aforementioned situations, it is found that at a fixed advertising level, the degree of influence of WOM is closely related to the level of advertising. The company’s advertising level significantly affects consumers’ estimations of product quality on the market. Higher advertising levels tend to make more consumers overestimate the product’s quality, exacerbating WOM’s negative impact. Conversely, if the company’s advertising level for the product is relatively low, resulting in most consumers underestimating the product’s quality, the positive impact of WOM should be further reflected. Therefore, to investigate the impact of advertising levels on corporate profits, the next section adjusts the parameter values of advertising levels to study the impact of advertising on companies’ dynamic evolutionary path.

5.2. Influence of Advertising Levels

Previous numerical experiments have shown that companies’ profits gradually decrease over time but ultimately stabilize, indicating that during the early stages of market development and changing consumer valuations, companies can achieve greater profits. This is primarily due to companies’ excessively high advertising level in such scenarios. Notably, in the first numerical experiment, the product quality was set to , while the advertising level was . This suggests that for consumers in the market, the company’s advertising easily steers their valuations above the actual product quality. Consequently, after purchasing the product, consumers experience a quality discrepancy that sharply reduces their maximum valuation due to the presence of WOM, a trend clearly observed in the graphs. As consumers’ maximum valuations of the product continue to decline, the impact of the company’s advertising level on consumer valuations persists, but WOM leads to fewer consumers estimating the product’s quality above its actual level, significant slowing down the decline in the company’s profits. In the long run, the negative impact of quality discrepancies in consumers’ quality expectations becomes less significant, and the growth and dissipation of this expected upper limit reaches equilibrium. Consequently, market demand and the company’s profits eventually stabilize. For the company, high profits are initially achieved through the guiding effect of advertising, but ultimately, the difference in actual quality stabilizes profits at a lower level.

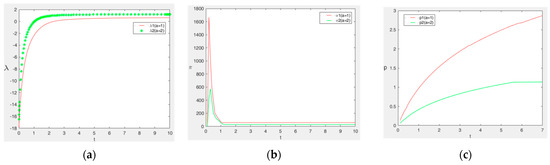

These findings reveal that the level of advertising can either enhance or mitigate the positive or negative impacts of WOM. Additionally, changes in advertising levels affect a company’s advertising costs. Therefore, in this section, we investigate the evolution of company profits when advertising levels change. First, we use the results from the first numerical experiment in Section 5.1 as a benchmark for comparative analysis. In this experiment, . In this section, the values of the adjusted advertising level are a = 1 and a = 2, respectively. The profit and company price formulas are shown in Table 4. The numerical simulation image is shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

The formulas for the effect of the advertising level a on price and profit.

Figure 2.

Influence of a on advertising level: (a) influence of a on symbiotic variable; (b) influence of a on profit ; (c) influence of a on company pricing .

The costate variables converge to 0 at the end of the system when . At this point, , the evolutionary paths of profit, and company pricing are shown below in Figure 2.

Proposition 4.

A decrease in the initial external advertising level leads to a gradual reduction in the company’s pricing level, resulting in a corresponding decrease in profit peaks.

By conducting numerical experiments adjusting the advertising level parameter, we discovered that as the degree of consumer WOM is held constant, lower advertising levels relative to the company lead to a gradual decrease in the final stable level of pricing, accompanied by reduced fluctuations in profits.

Compared with high-level advertising, a lower advertising level for the company results in consumers having a relatively lower product quality estimation before purchase. Consequently, more consumers’ quality estimations are below the actual product quality, which can promote the positive impact of WOM. However, from another perspective, a lower advertising level is disadvantageous for companies when promoting their products on the entire consumer market. This is because a low level of advertising reduces its impact within , making it difficult for consumers to significantly increase their valuation ceiling for the product. Consequently, this prevents a substantial increase in the number of consumers purchasing the product. Simultaneously, a lower advertising level implies that the company needs to spend less on advertising costs. Therefore, in determining the final pricing, the company does not need to compensate for this cost through higher pricing levels, resulting in some reduction in the stable pricing solution.

Since there is no significant increase in the number of consumers purchasing the product, coupled with a certain degree of reduction in the equilibrium pricing of companies, the profits of the company correspondingly decrease. This is reflected in the figure by a decrease in the peak of profits. Furthermore, through the analysis of numerical experiments in Figure 2, it can be observed that the company has a negative profit region. This is primarily because at the initial time t = 0, the company’s pricing is still low, resulting in low demand and, thus, minimal revenue. Simultaneously, the cost incurred by the company to produce and maintain the quality level of the products sold significantly impacts its profits. However, over time, the pricing of companies continues to increase, and WOM among consumers gradually spreads signals of product excellence. Consequently, enterprise profits rapidly increase, rendering them profitable in the current period. Nevertheless, continuously increasing pricing will somewhat reduce the number of consumers willing to purchase the product on the market. Since the total cost incurred by the company is fixed, profits ultimately exhibit a decreasing trend.

From the numerical experiments above, it can be observed that since the company does not make decisions on advertising levels, the impact of advertising on company profits primarily stems from advertising costs. A lower advertising level implies a reduction in companies’ total costs, which also translates into a decrease in pricing levels, as shown in the figure above. At this point, a lower advertising level primarily enhances the positive impact of WOM among consumers, enabling the company to generate profits. Notably, in some of the numerical experiments, there were instances where the companies’ pricing or profits had negative values. This can be partly attributed to the costs incurred by the company for product quality and partly to slight numerical errors arising from simplifications made during the calculation process based on this chapter’s dynamic model and costate variable settings. These findings do not indicate that a particular value is completely incorrect; rather, they illustrate that companies adjust their pricing for profit maximization based on different market conditions, including advertising levels, WOM, and so on, and their own cost considerations.

5.3. Degree of Influence of Other Parameters

In the first two sections of this study, we separately examined the impact and extent of WOM and company fixed advertising levels on long-term profits. In reality, the existence of advertising can influence the role of WOM among consumers in various directions. In fact, consumers’ estimation ceiling for product quality is influenced not only by WOM but also by companies’ fixed advertising level. As evident from the model settings, factors such as the saturation level of consumers’ estimation ceiling, denoted by , have a higher value, indicating that it is more difficult to increase consumers’ estimation ceiling because they will not indefinitely increase their estimation of a product’s quality. The coefficient for the natural decay of this ceiling can also have an impact on companies’ long-term profits. This section presents a numerical experimental analysis of such parameters to investigate the role and influence of other exogenous variables in the model.

First, the role of influence is studied as in Section 5.1. The first set of numerical experiments is used as a benchmark for the control.

Here, we keep the other parameters constant and adjust the value of .

Let .

By substituting these values, we have

And, at the same time,

The optimal profit function can be written as

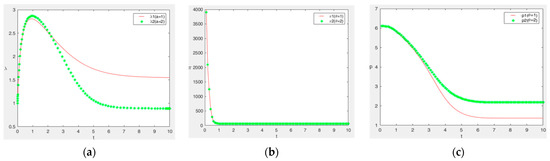

The costate variables converge to 0 at the end of the system when . At this point, , the evolutionary paths of profit, and company pricing are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Influence of on consumer quality estimation: (a) influence of on symbiotic variable ; (b) influence of on profit ; (c) influence of on company pricing .

In the following chapter, the influence of is similarly discussed.

Let .

By substituting the respective values, we have and, at the same time,

The optimal profit function can be written as

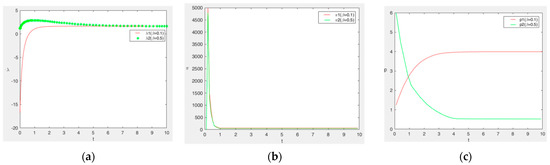

It is found that the costate variables converge to 0 at the end of the system when . At this point, , the evolutionary paths of profit, and company pricing are shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4.

Equilibrium state of variables at : (a) influence of on symbiotic variable ; (b) influence of on profit ; (c) influence of on company pricing .

Proposition 5.

When the market approaches saturation or consumers find it difficult to enhance their quality estimations, the profits attainable by enterprises remain relatively constant. However, when consumers’ quality estimations are more prone to natural decay, companies’ profits can decrease.

By comparison, as the value of increases, it becomes more difficult for the company’s advertising to enhance consumers’ estimation ceiling for product quality; yet, the company’s profits do not differ significantly from those in Section 5.1. The first set of numerical experiments, as shown in the figure, indicates that when consumers are less influenced by advertising, the company initially sets a relatively higher price. This is because consumers’ estimations of product quality are already difficult to increase; thus, most consumers choose to purchase the product initially, when WOM is not significant. By setting a relatively higher price, the company can quickly capture profits in the early stages. This is also the reason why the profit evolution path exhibits a faster change in the company’s profits. As time progresses, the company recognizes that in the presence of WOM, consumers’ experience of the product’s quality gap can lower the estimation ceiling of other consumers for product quality because the advertising level is relatively high at this point. Therefore, continuously setting high prices is more unfavorable to the company’s development. Consequently, the company chooses to gradually lower product pricing, resulting in gradually decreasing profits that ultimately stabilize. Since the factors influencing consumers’ final purchase decisions have not changed significantly and the product quality remains unchanged, the difference in profits between this scenario and the case where is not significant.

Similarly, as increases, the estimation ceiling for product quality decreases more rapidly. Consequently, the effect of increasing the estimation ceiling brought about by the company’s equivalent level of advertising, quality, and WOM is equivalent to being weakened. Under these conditions, consumers’ estimation ceiling for product quality is more prone to decrease, resulting in fewer consumers actually purchasing the product. This, in turn, leads to the company’s ultimate profits stabilizing at a lower level. Similarly, when the company operates in a market environment with a high advertising level and relatively insignificant WOM, it is a viable strategy to set higher prices initially to quickly capture profits. However, as time progresses, it becomes wiser to reduce prices.

6. Discussion

This study investigates the impact of WOM on optimal decision-making behavior for companies in the long term. Factors such as WOM, corporate advertising, and pricing play crucial roles in influencing company decisions during their development. From the perspective of dynamic system control, this research study first analyzes the extreme value variation patterns of dynamic pricing in companies. Subsequently, it explores how the presence of WOM, under the condition of external advertising levels, influences a company’s profits and pricing over an extended period. Additionally, the study examines the degree of influence of other market parameters on corporate profits, such as market saturation and the natural decay rate of consumer estimation. The dynamic nature of our model makes it highly relevant to e-commerce in the age of big data [56].

The research findings presented in this study, derived by applying the Hamiltonian function method, demonstrate that companies’ dynamic equilibrium pricing is correlated with WOM, advertising levels, and product quality. While these findings are similar to those reported by Feng and Zhang (2019) [56], these previous studies did not comprehensively discuss the interaction between WOM and advertising levels, two of the most prominent market factors, and their ultimate impact on companies. By analyzing the combined impact of WOM and advertising levels on companies, this study addresses some of the gaps in the literature on related topics.

Ouardighi et al. (2016) [30] explored dynamic pricing decisions under the influence of advertising and the effectiveness of WOM. The study divided WOM into two forms: advertising-dependent WOM, which relies on a company’s advertising efforts, and autonomous WOM, which develops beyond the company’s control. WOM effectiveness and current customer abandonment rate were taken as bifurcation parameters. The study found that the interplay among selling price, advertising dependence, and autonomous WOM can lead to complex dynamic pricing policies. The results are mainly applicable to monopolistic competitive markets. Similarly, Wang et al. (2019) [50] studied optimal dynamic pricing in the context of WOM, and for the first time, the dual role of WOM (positive and negative) was included in the utility of consumers from the individual level, primarily focusing on short-term strategic implications for companies. We considered the positive and negative effects of WOM on a consumer base. However, WOM has long-term implications for companies’ profits. By considering the long-term impact of WOM, Ajorlou (2018) [63] studied the problem of the optimal dynamic pricing of monopolistic companies through consumer word-of-mouth communication on social networks. The study found that optimal dynamic pricing strategies for durable products with zero or negligible marginal cost can reduce prices to zero infinitely frequently, and price fluctuations for non-durable products disappear after a limited time. The key role of product type in zero-price sales optimality was further revealed. Similar to this research, this study dealt with the long-term impact of WOM. We found that an increase in WOM intensity can reduce a company’s long-term profits at higher advertising levels, while a decrease in advertising levels may gradually lower pricing levels. But the difference is that our study did not focus on the effect of product type on dynamic pricing; we studied the consumer’s valuation of product quality.

This study also investigated the impact of market saturation and the natural depletion rate of consumers’ estimations of product quality on company profits. As Ouardighi et al. (2016) [30] mentioned, it is hoped to extend research to product quality and the influence of competitors. Godes (2017) [49] noted the relationship between WOM and product quality, with WOM ultimately helping people assess the utility of familiar products. Dou et al. (2021) [68] studied firms’ selling versus leasing models for information goods when the consumer valuation depreciates. The upper limit of consumers’ estimations of product quality is influenced not only by WOM and companies’ fixed advertising levels but also by the saturation level of these estimations and the coefficient for their natural depletion, which affects companies’ long-term profits. The findings suggest that companies’ profits remain relatively constant as the market approaches saturation or consumers find it harder to increase their quality estimations. However, companies’ profits decrease when consumers’ quality estimations are more prone to natural depletion. The contributions of this study are as follows:

- First, the literature on WOM, such as Ouardighi et al. (2016) [30] and Chevalier et al. (2006) [28], predominantly focuses on incorporating the quantities of different types of consumers in the market or the diverse market demands faced by enterprises as state variables in state transition equations. There is limited consideration of the influence of WOM on consumers’ valuation of products. By focusing on product valuation and examining how WOM influences consumers’ estimations, including their upper limits, this study offers a novel perspective on WOM research.

- Second, the dynamic nature of our model makes it highly relevant to e-commerce in the big data era. We contribute to the pricing literature by describing a mechanism that uses the Hamiltonian function method and dynamic simulation to construct a dynamic equation. Previous studies have focused primarily on the immediate impact of WOM on companies or consumers, neglecting the temporal persistence of these effects, as highlighted by Wang et al. (2019) [50]. To address this issue, this study employs a dynamic research approach to characterize the long-term impact of WOM on companies, thereby exploring optimal decision making in the long run.

- Third, current research tends to focus on online reviews as representative manifestations of WOM, with limited exploration of the interplay among brand effects, advertising levels, product quality, and their impact on company profits [35,55]. Our comprehensive analysis considers the long-term interplay among WOM, company advertising, pricing, and other factors. Empirical studies have primarily dominated this area. In contrast, this study uses the Hamiltonian function method and dynamic simulation to construct a dynamic equation. It comprehensively examines the evolution of company pricing and profits as consumers’ estimations of product quality change over time due to varying WOM intensities, considering factors such as company advertising.

7. Conclusions

The essence of word of mouth lies in consumers’ spontaneous sharing of information to promote products. As the internet has evolved, the means of disseminating WOM have gradually become more diverse. Drawing on the literature on the impact of WOM on consumer behavior and corporate decision making, this study adopts a dynamic approach to investigate the long-term pricing and profit changes of companies influenced by consumer WOM. By using Hamiltonian equation solutions and dynamic simulation methods, a dynamic equation is constructed to explore how company pricing and profit evolve as consumers’ valuations of product quality change over time due to varying WOM intensities. The model primarily considers the long-term constant advertising level set by enterprises based on external advertising levels, the pre–post discrepancy in consumer perception of product quality, and the natural decay of the upper limit of consumer valuation. This study comprehensively examines the changes in pricing and profit levels and their long-term evolutionary paths in a market influenced by WOM from multiple perspectives. It also discusses the interactive processes between WOM and advertising levels, the two most prominent market factors, and their ultimate impact on companies.

Through relevant propositions, numerical experiments, and dynamic simulations, the main findings are as follows:

- First, the optimal long-term pricing level of companies may increase with initial advertising investment. When advertising levels are high, consumers are likely to overestimate the quality of products; in contrast, when advertising levels are low, they may underestimate it. However, due to WOM, companies tend to slightly lower their pricing to prevent negative WOM generated among consumers from excessive pricing or mismatched product quality.

- Second, the impact of advertising on corporate profits primarily stems from advertising costs. High or low advertising levels can trigger positive or negative WOM, while changes in advertising levels also affect advertising costs. When the intensity of WOM among consumers is high, a higher advertising level gradually reduces corporate profits and stabilizes at a lower level. Conversely, a decrease in initial external advertising levels gradually reduces pricing levels and profits, which is unfavorable for long-term corporate development. These findings align with those of Caulkins et al. (2017) [59] and others.

- Third, if consumers’ estimations of product quality are near the upper limit, meaning that they are less swayed by advertising, a preferable strategy for companies is to set relatively high prices initially and gradually reduce them over time. During the early stages of market evolution, the saturation level of consumers in the market does not significantly impact long-term profits. Instead, the natural depletion rate of consumers’ upper limits for quality estimations significantly affects corporate profits.

These conclusions carry significant research implications. The dynamic equilibrium pricing of companies is correlated with WOM, advertising levels, and product quality. Depending on various conditions, companies’ advertising level is the primary factor determining the comparison and dissemination of their products’ reputation among consumers. When the intensity of the current WOM increases, a higher advertising level decreases the company’s long-term profits, and reduced external advertising levels may gradually lower enterprise pricing levels. In this scenario, companies can maximize their long-term profits by adopting a low-price strategy and earning WOM recognition.

Moreover, companies should adjust their advertising and pricing based on consumers’ estimations of product quality. It was found that consumers do not indefinitely increase their estimations of a product’s quality. As the market nears saturation, the profits earned by companies remain largely unchanged. Therefore, most consumers choose to purchase products when the initial WOM is insignificant, and companies can quickly capture profits in the early stages by setting relatively higher prices. However, when consumers experience a gap in product quality, the upper limit of other consumers’ estimations of product quality diminishes due to the relatively high advertising level. Consequently, continuously setting high prices is less conducive to companies’ development. Therefore, companies choose to gradually lower their product pricing, resulting in gradually decreasing profits that ultimately stabilize.

This study analyzes the impact of WOM on companies’ dynamic pricing and long-term profits. Nevertheless, this study has certain limitations, and further research is required in the future, as detailed in the following:

- This study establishes a system where a single company exists in the market, producing products of a certain quality level at a given production cost. The results do not apply to duopoly competition markets. Some scholars have paid attention to the dynamic pricing problem in the presence of enterprise competition. Dou, Ji, and Wu (2021) [65] analyzed the dynamic pricing decisions of firms by developing a model of oligopoly industries in which a firm can attract customers from their competitors by lowering its product prices. Their model allows firms to be different and to produce differentiated goods within an industry. Dai et al. (2022) [69] developed a tractable stochastic duopoly entry game, which has a novel implication on the second-mover advantage. Future research could extend duopolies to consider firm decisions with first-mover and late-mover advantages in dynamic pricing. In addition, the numerical simulation method is used to model the function in this research study, and future study will consider using real enterprise figures for further analysis.

- When studying the dynamic processes of companies in the long term, it is assumed that the initial advertising level of companies remains unchanged over time. However, with the continuous development of communication and review methods, the dissemination of WOM among consumers has become increasingly convenient. For companies, it may be necessary in some cases to continuously adjust their advertising investments based on consumer feedback in the long term [60]. In addition, when studying the dynamic process of the enterprise in the long run, the initial advertising level of the enterprise may affect the selling price and profit in the equilibrium. Future research may consider and analyze these aspects.

- Businesses and consumers have been focusing on environmentally sustainable products and services. Moise et al. (2019) [70] examined the relationship among environmental sustainability, brand dimensions, and WOM and found that “green” practices adopted by hotels have positive implications for guest word of mouth. Additionally, different formats of eWOM communications affect consumer behavior. Based on the key dimensions of the Metaverse environment (immersiveness, fidelity, and sociability), Mladenović et al. (2024) [71] developed the concept of sensory WOM. Future studies in this direction may consider more complex model constructions, such as analyzing scenarios with multiple control variables, state equations for companies, WOM mode, and so on.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L. and F.H.; data curation and methodology, H.Y.; investigation and writing—original draft, F.H. and Y.G.; writing—review and editing, B.L. and Y.G.; project administration, B.L.; funding acquisition, F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The following projects funded this research work: (1) Shanxi Science and Technology Strategy Research Project of China (grant No. 202304031401106). (2) Shanxi Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Research of China (grant No. 2023YY275). (3) Major Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant No. 21&ZD102).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Iyer, R.; Griffin, M. Modeling word-of-mouth usage: A replication. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagaty, M.D.; Dash, U. Digital Word-of-Mouth Dynamics: Unpacking the Influence of Product Engagement and Brand Perception. Anweshan 2023, 4, 18–34. [Google Scholar]

- Arsiyanti, L.; Sari, D.M. Electronic Word of Mouth and Brand Image in Social Media Instagram Context. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent System (ICORIS), Makassar, Indonesia, 25–26 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Bai, H. Information Usefulness and Attitude Formation a Double-Dependent Variable Model (DDV) to Examine the Impacts of Online Reviews on Consumers. J. Organ. End. User. Com. 2021, 33, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haudi, H.; Handayani, W.; Musnaini, M.; Suyoto, Y.; Prasetio, T.; Pitaloka, E.; Cahyon, Y. The Effect of Social Media Marketing on Brand Trust, Brand Equity and Brand Loyalty. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2022, 6, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, A. The influence of AI word-of-mouth system on consumers’ purchase behaviour: The mediating effect of risk perception. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2022, 39, 516–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadir, S.C.; Pauwels, K. When does word of mouth versus marketing drive brand performance most? J. Mark. Anal. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.N.; Laroche, M. Analyzing electronic word of mouth: A social commerce construct. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2017, 37, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaemingk, D. Online Reviews Statistics to Know. Qualtrics. 2023. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/online-review-stats/ (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Gharib, R.K.; Garcia-Perez, A.; Dibb, S. Trust and reciprocity effect on electronic word-of-mouth in online review communities. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 33, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Confente, I.; Vigolo, V.; Brunetti, F. The role of WOM in affecting the intention to purchase online: A comparison among traditional vs. Electronic WOM in the tourism industry. In Exploring the Power of Electronic Word-of-Mouth in the Services Industry; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 317–333. [Google Scholar]

- Harahap, D.A.; Hurriyati, R.; Gaffar, V.; Wibowo, L.A.; Amanah, D. Effect of Word of Mouth on Students’ Decision to Choose Studies in College. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Islamic Economics, Business, and Philanthropy ICIEBP 2017, Bandung, Indonesia, 15 November 2017; pp. 793–797. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, E. The Anatomy of Buzz, 1st ed.; Harper Collins Business: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jaehnig, E.J.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2019: Gene Set Analysis Toolkit with Revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids. Res. 2019, 47, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, L.A.; Yuan, W. Effect of individual and enterprise behaviors on the interplay between product-attributes information propagation and word-of-mouth communication in multiplex networks. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2023, 34, 2350009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, M.; Abbas, T.; Abrar, M.; Iqbal, A. EWOM and Brand Awareness Impact on Consumer Purchase Intention: Mediating Role of Brand Image. Pak. Adm. Rev. 2017, 1, 84–102. [Google Scholar]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N.; Pandey, N.; Mishra, A. Mapping the electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) research: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 135, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Anderson, C.K. Customer Motivation and Response Bias in Online Reviews. Cornell. Hosp. Q. 2020, 61, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnoor, A.; Tiberius, V.; Atiyah, A.G.; Khaw, K.W.; Yin, T.S.; Chew, X.; Abbas, S. How positive and negative electronic word of mouth (eWOM) affects customers’ intention to use social commerce? A dual-stage multi group-SEM and ANN analysis. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 808–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvili, Y.; Levy, S. Consumer engagement in sharing brandrelated information on social commerce: The roles of culture and experience. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 27, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. The effect of inconsistent word-of-mouth during the service encounter. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagin, A.J.; Metzger, M.J.; Pure, R.; Markov, A.; Hartsell, E. Mitigating risk in ecommerce transactions: Perceptions of information credibility and the role of user-generated ratings in product quality and purchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MajlesiRad, Z.; Shoushtari, A.H.H. Analysis of the impact of social network sites and eWOM marketing, considering the reinforcing dimensions of the concept of luxury, on tendency toward luxury brand. Future Bus. J. 2020, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talwar, M.; Talwar, S.; Kaur, P.; Islam, A.N.; Dhir, A. Positive and negative word of mouth (WOM) are not necessarily opposites: A reappraisal using the dual factor theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalwan, A.A.; Algharabat, R.S.; Baabdullah, A.M.; Rana, N.P.; Raman, R.; Dwivedi, R.; Aljafari, A. Examining the impact of social commerce dimensions on customers’ value cocreation: The mediating effect of social trust. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 18, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Wiertz, C.; Feldhaus, F. Does Twitter Matter? The impact of microblogging word of mouth on consumers’ adoption of new movies. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2015, 43, 375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H.H.; Wu, L.H. An examination of negative eWOM adoption: Brand commitment as a moderator. Decis. Support Syst. 2014, 59, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.A.; Mayzlin, D. The effect of word of mouth on sales: Online book reviews. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noort, G.; Willemsen, L.M. Online damage control: The effects of proactive versus reactive webcare interventions in consumer-generated and brand-generated platforms. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouardighi, F.; Feichtinger, G.; Grass, D.; Hartl, R.; Kort, P.M. Autonomous and advertising-dependent ‘word of mouth’ under costly dynamic pricing. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 251, 860–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarocas, C. Strategic manipulation of Internet opinion forums: Implications for consumers and firms. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1577–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, 1st ed.; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, X.; Kuik, S. Effect of word-of-mouth communication and consumers’ purchase decisions for remanufactured products: An exploratory study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Yu, Z.X.; Liu, F. Economical user-generated content (UGC) marketing for online stores based on a fine-grained joint model of the consumer purchase decision process. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 21, 1083–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartika, T.; Pandjaitan, D. Electronic Word-of-Mouth and Social Media Marketing on Brand Image and Purchase Intention. J. Ilm. Manaj. Kesatuan 2023, 11, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]