Encountering Product Information: How Flashes of Insight Improve Your Decisions on E-Commerce Platforms

Abstract

1. Introduction

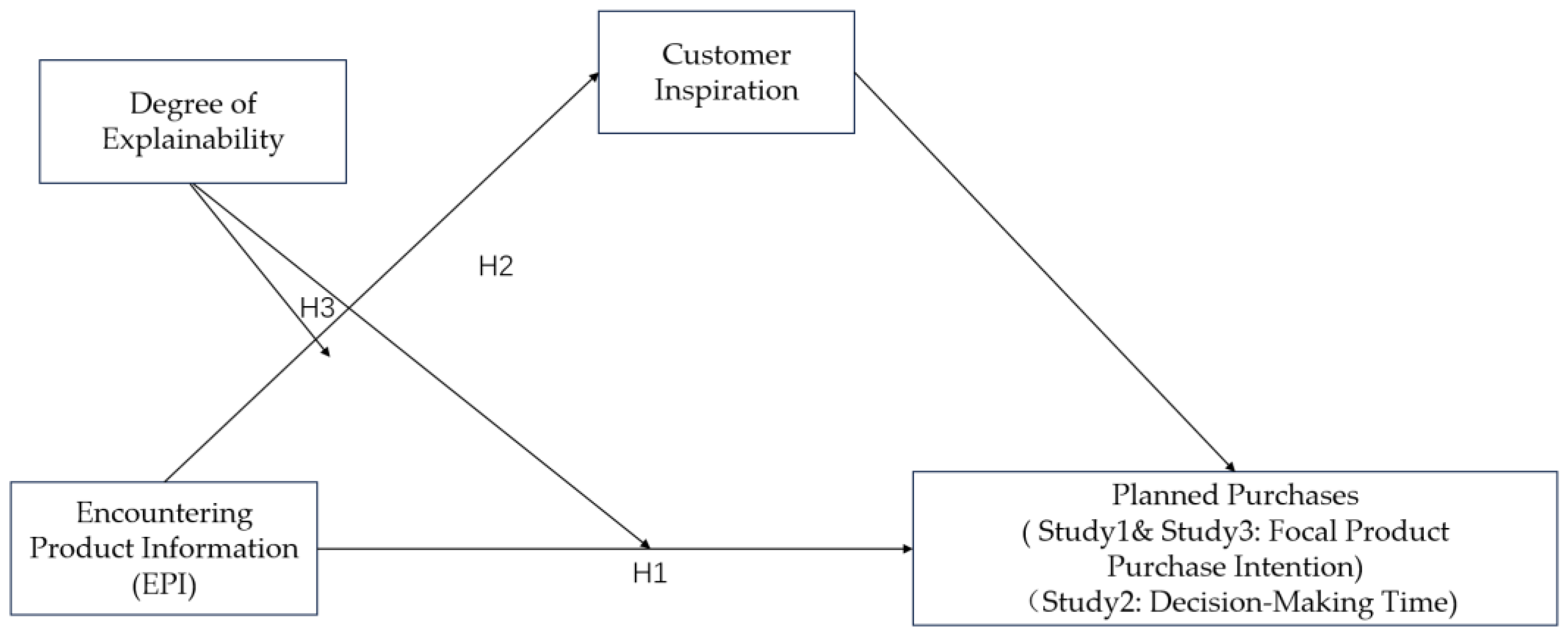

- Does encountering product information affect customers’ planned purchases (the focal product)?

- What is the underlying mechanism behind the effect of encountering product information on planned purchases (the focal product)?

- What are the boundary conditions of the main effects based on the characteristics of the recommender system strategy, the accessibility-knowledge framework, and customer inspiration?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Information Encountering (IE) and Encountering Information (EI)

2.2. The Impact of Encountering Product Information on Customers’ Decision-Making

2.3. Customer Inspiration

- containing deeply inspiring content (such as a new combination or new ideas);

- encouraging the use of imagination;

- an inspiring approach to motivation rather than avoidance motivation.

2.4. Characteristics of Recommender System Strategy: Degree of Explainability

3. Research Methodology and Data Analysis Results

3.1. Study 1: Verify the Main Effect of Encountering Product Information (EPI) on Intention to Purchase Focal Product

3.1.1. Participants and Design

3.1.2. Results

3.1.3. Discussion

3.2. Study 2: The Mediator Role of Customer Inspiration

3.2.1. Participants and Design

3.2.2. Results

3.2.3. Discussion

3.3. Study 3: Characteristics of Recommender System Strategy: Degree of Explainability

3.3.1. Participants and Design

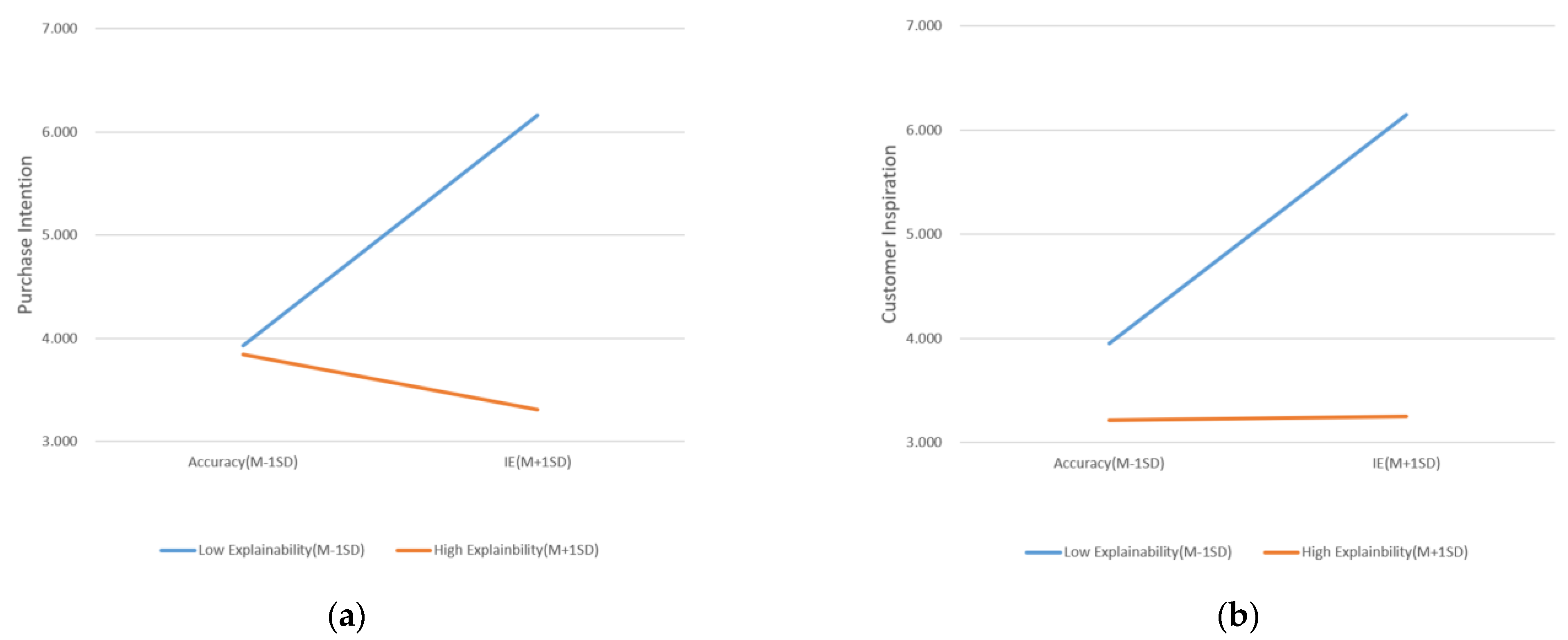

3.3.2. Results

3.3.3. Discussion

4. Discussion

4.1. Conclusions

- Encountering product information has a favorable effect on the desire to purchase the focal product, with customer inspiration serving as the underlying psychological mechanism. In contrast to the absence of EPI (as seen in an accuracy-oriented recommender system), EPI can effectively encourage customers with premeditated consumption habits to identify and acquire the focal product. This discovery is intrinsically linked to customer inspiration. Drawing from the Theory of Knowledge Accessibility, EPI that surpasses expectations and stands out has the potential to captivate and motivate customers with relevant background knowledge to recognize its worth, evoke association, and ultimately spark the drive to make the purchase;

- The level of explainability in a recommender system plays a crucial role in how product information affects customer inspiration and purchase intent. Our research shows that utilizing a low-explainability strategy results in a more significant positive impact on both, compared to a high-explainability approach.

4.2. Theoretical Implications

- This study has contributed to marketing research by enhancing our understanding of the relationship between encountering product information and customer decisions. Previous research in the marketing field has highlighted the importance of unexpectedness in IE, which is considered a positive, unexpected occurrence that brings about feelings of surprise or luck [14]. However, our study highlights the significance of encountering information as a valuable resource in itself, revealing hidden connections or analogies between unrelated things. This can aid customers with prepared minds to make informed product decisions, streamline their searches, and reduce decision-making time [21,22];

- The previous literature on the impact of IE on customer decision-making behavior has concentrated solely on impulsive purchases. These studies suggested that IE can encourage customers to prefer the products encountered and ultimately increase their intention to purchase them [6]. Nevertheless, this study revealed that unexpected encounters can positively impact intentional purchases. In particular, this research demonstrated that information obtained from unplanned encounters can effectively motivate customers to promptly and confidently choose the desired product from an overwhelming array of recommended options;

- This study seamlessly merges two theories, knowledge accessibility and customer inspiration, to explore the impact of encountering product information on customer decision-making. Prior research on customer inspiration identified arousal, transcendence, and motivation as key components. Arousal typically stems from external stimuli that intersect with customers’ existing knowledge, experience, and common sense. However, less attention has been paid to customers’ own background knowledge. This study introduced knowledge accessibility theory to enrich our understanding of how background knowledge and external stimuli interact to produce customer inspiration and impact subsequent behavior [35].

4.3. Pratical Implications

- By actively adopting a serendipity-oriented recommender system, e-commerce platforms can make full use of encountering product information to reduce the amount of search friction on the platform [42] in order to achieve higher efficiency and improve profit margins. To optimize recommender systems, platform managers should consider increasing the flexibility of recommendations. When customers are overwhelmed by a large number of items, the system should proactively suggest products that may not have a high match with the current search terms but align with the user’s profile [43]. This approach not only enhances the unpredictability of recommendations but also piques customers’ curiosity, increases the appeal of recommended items, and raises their perceived value. By introducing some inconsistency into the product selections, customers may be inspired to explore further, ultimately leading to increased consumption of focal products;

- Explainability, a mitigator of the algorithmic black-box effect, should be carefully reduced in serendipity-oriented recommender systems. In this study, customer inspiration was found to be an underlying mechanism for the intention to purchase the focal product by encountering product information; however, a higher degree of explainability may trigger customers to attribute the role of the platform or back-end managers, which in turn reduces the traceability and associations of the differences between the encountered product and the searched product, and inhibits the positive effect of customer inspiration in the effect of EPI;

- By incorporating encountering information into recommender systems, we can enhance customer protection. Although our research was focused on the perspectives of platforms and retailers rather than customers, encountering information does improve customers’ experiences. This information helps protect customers from “filter bubbles” and expands their horizons by allowing them to explore areas they may have overlooked due to the precision-focused nature of recommender systems;

- Serendipity-oriented recommender systems ensure diversity in product offerings and support the visibility and sales of both long-tail and cold-start products, benefiting the health of sellers.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

- In order to fill the gap in the research of planned consumption caused by information encountering, this study focuses on the perceived value of encountering product information itself as a pre-variable for enhancing the intention to purchase focal products. However, encountering product information (content) is inherently embedded within information encountering (event). Future research could consider whether planned customers, when simultaneously influenced by the unexpectedness of information encountered and the value of encountering product information, have more intent to make unplanned consumption decisions (encountering product purchases) or to reinforce planned consumption goals and quickly make planned consumption decisions (focal product purchases);

- While this study has confirmed that customer inspiration plays a mediating role in the effect of EPI on focal product purchase intention, there may be additional mechanisms at play that can more fully explain this effect. For example, how does encountering product information help customers to identify their desired products more efficiently (target identification) and reject competing products more quickly (competitor rejection), ultimately leading to smoother transactions [44]?

- As per current platform practices, the sources of encountering product information are becoming increasingly diverse. Along with the algorithm-generated product information curated by platform administrators through supplementary tools like the “Random Information Node Generator” [45], there is also encountering product information from user profile data and that shared by others with added social elements. This presents an opportunity for future research to examine the impact of encountering product information from diverse sources on customer behaviors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ziarani, R.J.; Ravanmehr, R. Serendipity in Recommender Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2021, 36, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funta, R. Relationships between Platforms and Retailers (on the Example of Amazon). Auc Iurid. 2023, 69, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, C.; Benbasat, I.; Burton-Jones, A. With a Little Help from My Friends: Cultivating Serendipity in Online Shopping Environments. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makri, S.; Blandford, A. Coming across Information Serendipitously—Part 2: A Classification Framework. J. Doc. 2012, 68, 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peráček, T. E-Commerce and Its Limits in the Context of the Consumer Protection:The Case of the Slovak Republic. TBJ 2022, 12, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Erdelez, S.; Thome, J. Online Consumer Information Encountering Experience for Planned Purchase and Unplanned Purchase. In Proceedings of the 2011 iConference, Seattle, WA, USA, 8–11 February 2011; ACM: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011; pp. 794–795. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Séaghdha, D.Ó.; Quercia, D.; Jambor, T. Auralist: Introducing Serendipity into Music Recommendation. In Proceedings of the Fifth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining—WSDM ’12, Seattle, WA, USA, 8–12 February 2012; ACM Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2012; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- David, P.; Song, M.; Hayes, A.; Fredin, E.S. A Cyclic Model of Information Seeking in Hyperlinked Environments: The Role of Goals, Self-Efficacy, and Intrinsic Motivation. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2007, 65, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.M.; Erdelez, S. Distraction to Illumination: Mining Biomedical Publications for Serendipity in Research. Proc. Assoc. Info. Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.L.; Tanford, S. The Windfall Gain Effect: Using a Surprise Discount to Stimulate Add-on Purchases. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 95, 102918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Chou, T. Research on the Feature Convergence Effect Based on Context Cue. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2012, 15, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, C.; Hoyer, W. Planned versus Impulse Purchase Behaviour. J. Retail. 1986, 62, 384–409. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A. The Effects of Chance and Romantic Motives on Consumer Preferences. Ph.D. Thesis, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.; Affonso, F.M.; Laran, J.; Durante, K.M. Serendipity: Chance Encounters in the Marketplace Enhance Consumer Satisfaction. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Briley, D. Finding the Self in Chance Events. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 853–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, C.; Benlian, A.; Hess, T.; Weiß, C. Escaping from the Filter Bubble? The Effects of Novelty and Serendipity on Users’ Evaluations of Online Recommendations. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Information Systems, Auckland, New Zealand, 14–17 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- e Cunha, M.P.; Clegg, S.R.; Mendonça, S. On Serendipity and Organizing. Eur. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, T.; Vetere, F.; Howard, S. Abdicating Choice: The Rewards of Letting Go. Digit. Creat. 2008, 19, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.G.; Suri, S.; McAfee, R.P.; Ekstrand-Abueg, M.; Diaz, F. The Economic and Cognitive Costs of Annoying Display Advertisements. J. Mark. Res. 2014, 51, 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Chu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, R.; Lan, B.; He, L. Effect of Serendipity in an Encounter on Purchase Intention of Unexpected Products. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 848907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdelez, S.; Makri, S. Information Encountering Re-Encountered: A Conceptual Re-Examination of Serendipity in the Context of Information Acquisition. J. Doc. 2020, 76, 731–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rond, M. The Structure of Serendipity. Cult. Organ. 2014, 20, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdelez, S. Investigation of Information Encountering in the Controlled Research Environment. Inf. Process. Manag. 2004, 40, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qin, C.; Ma, X.; Liang, H. Serendipity in Human Information Behavior: A Systematic Review. J. Doc. 2022, 78, 435–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A.; Ford, N. Serendipity and Information Seeking: An Empirical Study. J. Doc. 2003, 59, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenman, M.F. Serendipity and Scientific Discovery. J. Creat. Behav. 1988, 22, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdelez, S. Information Encountering: It’s More Than Just Bumping into Information. Bul. Am. Soc. Info. Sci. Technol. 2005, 25, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Messinger, P.R.; Li, J. Influence of Soldout Products on Consumer Choice. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shocker, A.D.; Bayus, B.L.; Kim, N. Product Complements and Substitutes in the Real World: The Relevance of “Other Products”. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.J.; Ratneshwar, S.; Shocker, A.D.; Bell, D.; Bodapati, A.; Degeratu, A.; Hildebrandt, L.; Kim, N.; Ramaswami, S.; Shankar, V.H. Multiple-Category Decision-Making: Review and Synthesis. Mark. Lett. 1999, 10, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettibone, J.C.; Wedell, D.H. Testing Alternative Explanations of Phantom Decoy Effects. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2007, 20, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.; Hong, J.; Chernev, A. Perceptual Focus Effects in Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrash, T.M.; Elliot, A.J. Inspiration: Core Characteristics, Component Processes, Antecedents, and Function. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 957–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttger, T.; Rudolph, T.; Evanschitzky, H.; Pfrang, T. Customer Inspiration: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Validation. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyer, R.S., Jr. The Role of Knowledge Accessibility in Cognition and Behavior. In Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-203-80957-0. [Google Scholar]

- Adaval, R.; Wyer, R.S., Jr. Conscious and Nonconscious Comparisons with Price Anchors: Effects on Willingness to Pay for Related and Unrelated Products. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, Z. The Mechanism of Brand Alliance Attitude toward Cross-over Co-development: Based on the Perspective of Consumer Inspiration Theory. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2021, 24, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D. The Effects of Explainability and Causability on Perception, Trust, and Acceptance: Implications for Explainable AI. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2021, 146, 102551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, M.S. Conceptual Metaphors and Figurative Language Interpretation: Food for Thought? J. Mem. Lang. 1996, 35, 544–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Hoyer, W.D. The Effect of Novel Attributes on Product Evaluation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willemsen, M.C.; Graus, M.P.; Knijnenburg, B.P. Understanding the Role of Latent Feature Diversification on Choice Difficulty and Satisfaction. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2016, 26, 347–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Netessine, S. Higher Market Thickness Reduces Matching Rate in Online Platforms: Evidence from a Quasi-Experiment. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Jiang, Z.; Benbasat, I. Designing for Diagnosticity and Serendipity: An Investigation of Social Product-Search Mechanisms. Inf. Syst. Res. 2017, 28, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Lans, R.; Pieters, R.; Wedel, M. Online Advertising Suppresses Visual Competition during Planned Purchases. J. Consum. Res. 2021, 48, 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaquinta, L.; De Gemmis, M.; Lops, P.; Semeraro, G.; Filannino, M.; Molino, P. Introducing Serendipity in a Content-Based Recommender System. In Proceedings of the 2008 Eighth International Conference on Hybrid Intelligent Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 10–12 September 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 168–173. [Google Scholar]

| Source | Effect | Product Types | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ge, Messinger, and Li (2009) [28] | Information Cascades Effect | Sold-out products | The existence of out-of-stock products within the context of decision-making can motivate customers to purchase the currently available options and ultimately reduce the tendency to delay making a choice. Two underlying decision processes: a sense of urgency and perceived attractiveness of products similar to the sold-out products. |

| Shocker, Bayus, and Kim (2004); Russell (1999) [29,30] | Cross- Category Effects | “Other Products” | “Other products” can directly or indirectly affect buyer demand for the focal product. The demand for the focal product may also be connected to the demand for products in other categories. |

| Pettibone and Wedell (2007) [31] | Phantom Decoy Effects | Phantom Decoy | The decoy options can contextually influence customers’ purchasing decisions regarding available options. There are three explanations for this effect: similarity to the phantom, perceived losses and gains, or the relative weighting of dimensions. |

| Sun and Zhou (2012); Hamilton, Hong | Feature Convergence Effects | Products with similar attributes | Customers are more willing to choose similar products to ensure quality and reduce risk. |

| Chernev (2007) [11,32] | Perceptual Focus Effects | Due to excessive exposure to similar attributes, people focus on unique attributes. |

| Research Purpose | Research Design | |

|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Verify whether encountering product information affects focal product purchase intention (H1) | Between-groups experiment; 2 (encountering product information: presented vs. not presented) × 1 (focal product purchase intention) |

| Study 2 | Verify the mediating role of customer inspiration (H2) and rule out alternative explanation (novelty) | Between-groups experiment; 2 (encountering product information: presented vs. not presented) × 1 (time of decision-making) |

| Study 3 | Examined explainability as a moderator in the effect of encountering product information on focal product purchase intention (H3) | Between-groups experiment; 2 (condition: IE vs. accuracy) × 2 (explainability: high vs. low) |

| Variables | Measurement | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|

| Encountering product information perception | I feel that some recommended products are unexpected. I feel that some recommended products are interesting. I am inspired by some recommended products. I am surprised by some recommended products. | 0.777 |

| Focal product Purchase intention | I would buy the English learning machine on this platform immediately. I would like to buy the English learning machine on this platform. | 0.657 |

| Customer inspiration | I was stimulated to imagine something. I got a new idea unexpectedly and spontaneously. My mind was broadened. Aha, it looks like it could be like this! | 0.878 |

| Novelty | I found the list of recommendations to be new. I found the list of recommendations to be fresh. I found the list of recommendations to be novel. | 0.827 |

| The time of decision-making | Collected from Camtasia Studio. | |

| Explainability | I understand why this product was recommended to me. This cue explains the system’s intention of recommending it to me well. I learned about the mechanism of recommender system. | 0.769 |

| Effect | SE | t | p | LLCT | ULCT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.321 | 0.052 | 6.270 | <0.001 | 0.220 | 0.422 |

| Direct effect | 0.129 | 0.045 | 2.829 | <0.01 | 0.038 | 0.218 |

| Indirect effect | 0.192 | 0.038 | / | / | 0.117 | 0.268 |

| Explainability | Effect | SE | LLCT | ULCT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1.4477 | 0.280 | 0.541 | 0.186 | 0.396 |

| 0 | 0.179 | 0.035 | 0.116 | 0.254 |

| 1.4477 | 0.785 | 0.309 | 0.217 | 0.143 |

| Moderated mediation | −0.069 | 0.018 | −0.110 | −0.039 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, D. Encountering Product Information: How Flashes of Insight Improve Your Decisions on E-Commerce Platforms. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 2180-2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030106

Wang L, Zhang G, Jiang D. Encountering Product Information: How Flashes of Insight Improve Your Decisions on E-Commerce Platforms. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2024; 19(3):2180-2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030106

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lu, Guangling Zhang, and Dan Jiang. 2024. "Encountering Product Information: How Flashes of Insight Improve Your Decisions on E-Commerce Platforms" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 19, no. 3: 2180-2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030106

APA StyleWang, L., Zhang, G., & Jiang, D. (2024). Encountering Product Information: How Flashes of Insight Improve Your Decisions on E-Commerce Platforms. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(3), 2180-2197. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19030106