Abstract

While the prior mobile payment−subjective well-being (SWB) literature has mainly discussed its economic and social impacts, the present study supplements this body of research by introducing an economic–social–environmental perspective. Using two waves of representative Chinese national surveys, the instrumental variable (IV) estimator suggests that mobile payment is positively and statistically significantly correlated with SWB. Furthermore, the results reveal that the positive correlation comes from the compound influence of economic, social, and environmental channels. Specifically, it shows that mobile payment not only affects people’s economic and social performance but also mitigates the adverse effects of poor environmental conditions on SWB. Additionally, a further disaggregated analysis shows that mobile payment exerts a stronger positive influence on SWB for people from underdeveloped areas within the economic–social–environmental framework. These findings shed light on the role of financial technology in facilitating sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Well-being is crucial for social development, which not only reflects people’s attitudes towards their life but also is an important embodiment regarding the quality of economic development and public welfare in a country [1,2,3,4]. As stated in the resolution adopted by the 66th United Nations General Assembly on 28 June 2012, well-being is the universal goal and aspiration in people’s lives worldwide [5]. Meanwhile, the resolution pointed out the need to adopt a more inclusive, equitable, and balanced approach to economic growth that promotes sustainable development, poverty eradication, and the well-being of all peoples.

Recently, with the wide application of Internet technology in financial systems, financial technology (fintech) has boomed worldwide and is considered to have tremendous potential in facilitating financial inclusion [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. There is growing evidence that increasing financial inclusion or enabling more vulnerable groups to access financial services is critical to a region’s economic growth, income distribution, and public well-being [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. In particular, mobile payment, as one aspect of financial technology, has become an effective and popular transacting tool in recent years, reshaping the business model and the way people use the Internet [20]. According to GSMA Intelligence, the number of registered mobile money accounts worldwide reached 1.75 billion in 2023, processing USD 1.4 trillion in transactions per year [21]. The rise of mobile payment not only promotes the demonetization and mobility of payment methods but also brings people a new lifestyle, such as a sharing economy. Against this backdrop, a growing number of studies are attempting to investigate the connection between mobile payments and the physical world, as well as their impacts on individual welfare. These studies mainly focus on the reasons why people use mobile payment [20,22,23,24,25]; its differences from cash payment or credit card payment, such as the convenience of remote payment, the avoidance of queues, and being more convenient and cost-effective [26,27,28]; and its impact on people’s consumption activities [29,30,31,32,33].

Additionally, a few studies have directly explored the impact of mobile payment on individual well-being. For example, Zheng and Ma [34] examined the correlation between mobile payment and subjective well-being (SWB). The study by Wu et al. [35] investigated the effect of mobile payment adoption at the household level on the well-being of rural householders. However, the research on the association between mobile payment and individual well-being is still insufficient. Importantly, individual well-being is not only affected by economic and social factors (e.g., income status and consumption), but also determined by the natural environment. Although prior studies have identified several economic and social mechanisms by which mobile payment affects well-being [35,36], they have overlooked the role of how mobile payment alters the impact of the external environment on people’s well-being. In fact, the popularity of mobile payment has promoted the rise of the paperless money era, making people’s transaction activities break through the restrictions of time and space. In the pre-mobile payment era, many transactions needed to be conducted face-to-face offline, and people often spend a certain amount of time in a specific outdoor space. This makes it difficult to avoid exposure to harsh external environments during the transaction process, such as conducting transactions near construction sites or dirty selling areas. By comparison, with mobile payment technology, people do not necessarily have to use tangible paper money, nor do they have to engage in face-to-face trading activities offline. These contactless changes allow people to avoid the potential negative effects of a poor external environment (such as air pollution or noise pollution) on their well-being in many situations.

To fill the gap, this work attempts to contribute to the existing literature by exploring the influence of mobile payment on an individual’s SWB and the mechanisms by which this association appears from a more comprehensive and novel channel, namely, the economic–social–environmental perspective. Accordingly, we adopt data from the 2017 and 2018 waves of the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) and find a statistically significant and positive correlation between mobile payment and SWB. Furthermore, our study indicates that this positive association is attributable to the multifaceted influence of mobile payment across the economic, social, and environmental dimensions, jointly shaping individuals’ SWB.

Consequently, this study provides three novel contributions. Firstly, it complements the literature about the impact mechanism of mobile payment on SWB. This paper examines how mobile payment affects an individual’s SWB from the economic–social–environmental perspective by addressing both environmental conditions and the socioeconomic factors. Secondly, we extend the research on environmental quality and well-being. The environmental literature has a long history of exploring the link between external environmental quality and individual well-being. However, the related literature has not considered how the popularity of mobile payment changes and influences the relationship. Thirdly, the work provides several ideas for other developing countries to implement a people-oriented sustainable development strategy via digital technology. Our study gives new evidence for the non-economic effects of mobile payment, particularly in non-western contexts. Interestingly, China, the world’s largest developing country, is now the global leader in mobile payment applications, despite its low credit card ownership in the past. Data show that China’s mobile payment users exceeded 900 million in 2024 [37], and mobile payment has become the most popular payment method for consumers. Therefore, the research based on China’s scenario can contribute compelling evidence of how the emergence of new payment methods affects people’s social welfare. Moreover, we also find that the promotion effect of mobile payment on individuals’ SWB is non-homogenous, which is more obvious for people from underdeveloped areas within the economic–social–environmental system. The conclusion provides some policy implications for enabling inclusive growth via digital technologies.

This paper is organized as follows: first, to prompt the empirical estimates, we give a brief literature review and propose the theoretical framework; second, the data source, model and variables selection, and descriptive analysis are presented; third, the empirical results and related discussions are shown; lastly, the conclusion and policy implications are discussed.

2. Previous Literature and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Determinants of Individual Well-Being

Ever since the proposal of the “Easterlin Paradox” [38], investigating the potential factors that influence individual well-being has become a persistent topic for economists and sociologists. A large number of studies have confirmed that the determinants of people’s well-being are complex, including not only material factors [39,40,41,42,43,44] and non-material factors (such as environmental quality) [45,46,47,48], but also individual factors [49,50,51] and the institutional environment in which one is located [52,53,54]. In addition, as participants in a social system, people’s well-being also depends on the object or group with which they are compared [55,56,57].

Meanwhile, the past two decades have witnessed tremendous progress in information and communication technology (ICT), which has made Internet technology inextricably linked to human life [58]. Under such background, a subject of research has been the exploration of how Internet technology affects individual well-being. Nevertheless, this link and the mechanisms by which it occurs have not reached a consensus yet. For instance, some studies suggest a positive correlation between Internet use and individual well-being [59,60,61,62,63,64], while others find a negative one [55,65,66,67,68]. As pointed out by Castellacci et al. [69], Nie et al. [70], and Gordon et al. [71], this contradictory connection is influenced by various factors, such as the choice of proxies for well-being, the purpose and intensity of people’s access to the network, and how they use the Internet in specific areas to promote well-being. Additionally, regional disparities in information technology development and its integration into social progress also contribute to the complexity of the Internet’s impacts on individual well-being.

2.2. Influence of Mobile Payment on SWB: The Economic–Social–Environmental Perspective

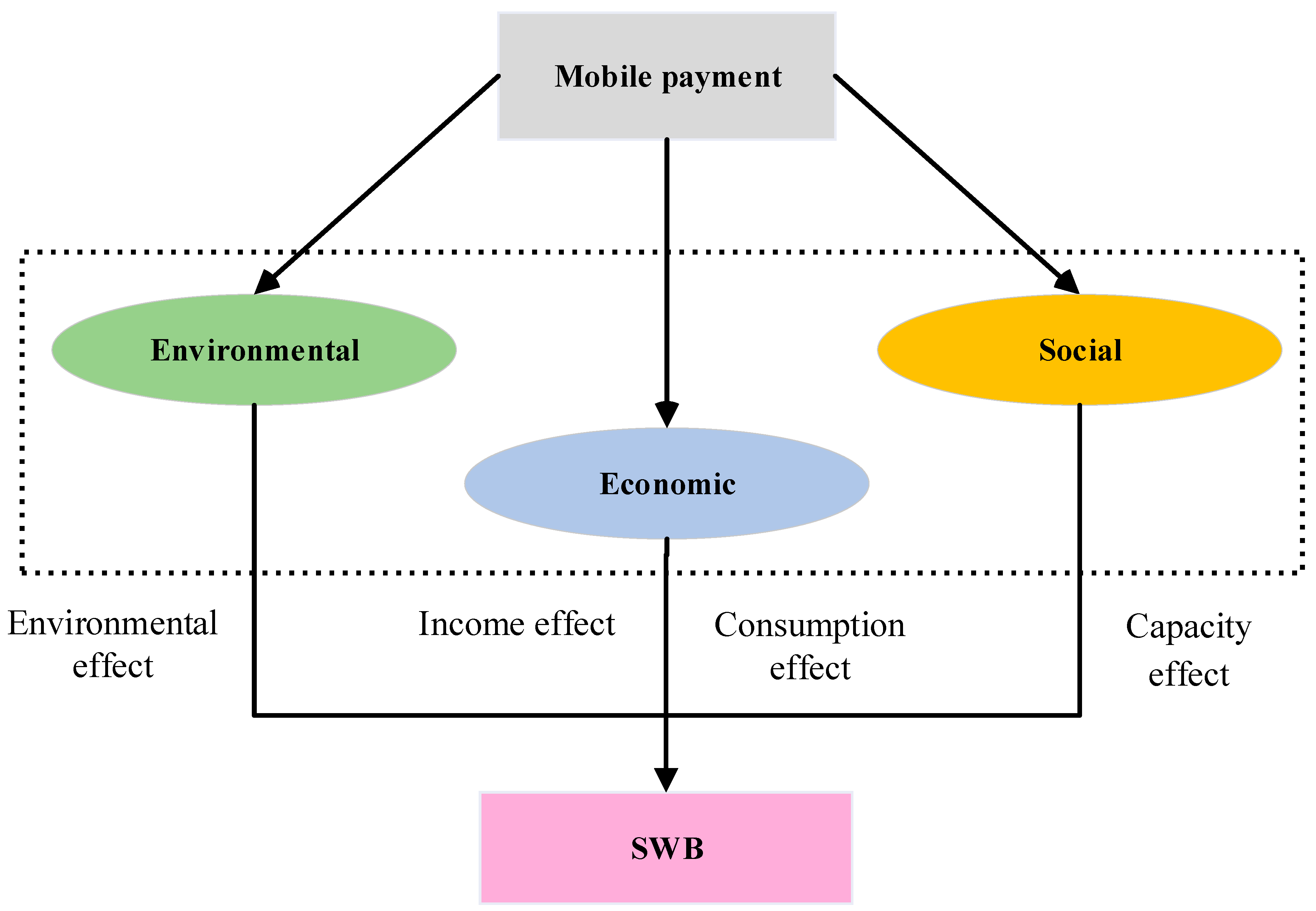

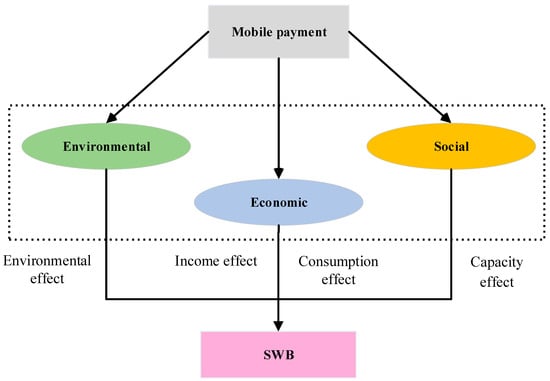

As indicated in the literature review part, SWB is determined by multidimensional factors from economic, social, and environmental systems. Therefore, we briefly summarize the connection between mobile payment and SWB from an economic–social–environmental perspective (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mobile payment and SWB: theoretical framework.

Firstly, as for the economic aspect, we argue that mobile payment can influence individual SWB via the income effect and consumption effect. Specifically, the income effect can be reflected in three aspects: (1) The popularity of mobile payment greatly replaces the traditional transaction method (e.g., cash and offline transactions) and has significantly reduced the transaction costs [35], thus promoting the operational efficiency of human activity. (2) As an aspect of financial inclusion, mobile payment can help reduce financial exclusion, providing more people with greater access to financial services for productive decision-making. In particular, people in low-income or economically underdeveloped areas often face severe financial constraint and have difficulty obtaining financial services from traditional institutions to meet their production needs, such as entrepreneurial activities. In prior works, achieving financial inclusion was regarded as an effective measure to reduce poverty [19,72,73,74,75,76]. In China, for instance, many apps (e.g., WeChat and Alipay) for mobile payment have the function of providing credit services. These financial services usually have low requirements for their users, which can effectively alleviate the credit constraints faced by people, who are excluded by the traditional financial institutions. (3) The popularity of mobile payment can facilitate more people engaging in online wealth management activities, thus increasing people’s income diversity. In general, the scarcity of financial services and financial literacy is one of the main factors limiting family venture capital investment and achieving effective wealth management [77,78,79,80]. The spread of mobile payment allows more people to understand and use financial products online, influences their perceptions of wealth and the risk appetite, and gives more people the opportunity and courage to participate in wealth management activities.

In terms of the consumption effect, mobile payment may have two opposite effects on SWB. On the one hand, the popularity of mobile payment helps to bring people a better consumption experience [81]. The rise of mobile payments has promoted the era of paperless money and greatly reduced offline transaction costs [33], which not only absolutely changes the way people complete commodity transactions, but also improves the transaction efficiency. Meanwhile, mobile payment has promoted the prosperity of online shopping. Especially for people living in underdeveloped areas, online shopping channels can effectively address the restrictions on consumption activities caused by geographical factors. Additionally, as discussed above, mobile payment has the potential to promote financial inclusion, which should reduce the liquidity constraints faced by poor households. This advantage helps increase the flexibility of their consumption decisions [82], thereby enhancing individuals’ SWB. On the other hand, however, the changes in people’s consumption activities brought about by mobile payment do not necessarily lead to an increase in their SWB. Although mobile payment makes it easier for people to participate in online shopping, it may also crowd out their offline consumption. Moreover, frequent online shopping may reduce people’s SWB. For example, they may face a large amount of commodity information, which can increase the complexity of product selection and the frequency of returns and exchanges. In addition, mobile payments can stimulate people’s irrational consumption behaviors and increase the risk of overspending [31,83], which may ultimately have a negative influence on the long-term welfare of families.

Secondly, the social channel indicates that mobile payment can influence individual SWB by their perception of the capacity to access social resources (denoted by the capacity effect). In the other word, we propose that the popularity of mobile payment is conducive to improving the capacity of a wider population to access social resources, thus boosting their SWB. According to Sen’s capability approach, the absence or deprivation of capacity is a major cause of poverty and welfare loss [84,85,86,87]. As a general-purpose technology, the role of ICT in alleviating social inequality has been extensively studied in previous studies [88,89]. As aforementioned, mobile payment has potential to provide more people with modern financial services at a lower cost and achieve financial inclusion. Additionally, the popularity of mobile payment also enables more people to complete commodity transactions without leaving home, which greatly improves the breadth and scope of financial and commercial services and allows more remote areas and economically disadvantaged populations to enjoy the benefits of social development. Moreover, apart from the effects on financial and consumption activities, many apps also integrate mobile payment with other activities in residents’ daily life. For instance, WeChat and Alipay encompass numerous functions such as healthcare, job hunting, travel, education, and government affairs, which allow people to access various social resources and services using only their smartphones. As a result, the popularity of mobile payment can promote more people to obtain social resources, thus improving their perception of their capacity to access social resources and increasing their SWB.

Thirdly, we hold that mobile payment may affect the relationship between the external environment and the individual SWB (denoted by the environmental effect). Theoretically, numerous studies have underscored the significance of a favorable natural environment, such as air quality and green coverage, in bolstering people’s SWB [47,48,90,91]. In the age of paper money, people often had to conduct transaction activities face-to-face, which made the external environment have a direct impact on their physical and mental well-being. Especially in areas with serious environmental pollution, people are more vulnerable to the risk of environmental pollution when conducting offline transactions. However, mobile payment enables people to pay bills and make purchases online without having to physically visit an offline location. It also allows more people to work from home or elsewhere, reducing the negative impact that environmental pollution can have on their quality of life while commuting. As a result, mobile payment makes people more flexible in their choice of activity space and time, which can reduce the direct impact of poor environment quality on their SWB.

As discussed above, mobile payment can influence an individual’s SWB via the multi-dimensional channels of the economy, society, and environment. However, the combined effect of this impact is inconclusive. Therefore, this study further adopts an econometric method to investigate the association between the two variables and test the underlying mechanisms.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Source

The objective of our work is to identify the impact of mobile payment on an individual’s SWB. Among the published micro-survey data in China, the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS) and CGSS are two commonly used datasets that include both mobile payment- and SWB-related information. However, mobile payment information in the CHFS is mainly at the household level. Therefore, we adopt the data of the publicly published CGSS conducted in 2017 and 2018 (i.e., CGSS2017 and CGSS2018) in our study. The CGSS is one of the most-used datasets in China, which is implemented by the National Survey Research Center (NSRC) at Renmin University of China. This project adopts the multi-order stratified PPS random sampling to conduct a continuous cross-sectional survey of more than 10,000 households in China each year. The survey collects data at the social, community, household, and individual levels, providing multiple perspectives on China’s social development. Awan et al. [92], Deng and Yu [93], Zhang et al. [94], Zhang and Jiang [95], and Song et al. [96] all have employed the CGSS to study social problems in contemporary China (for more detail: http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/ (accessed on 10 April 2024)). Accordingly, a total of 12,582 and 12,787 samples were interviewed in CGSS2017 and CGSS2018, respectively. The two waves of the CGSS covered 28 provinces/municipalities directly under the central government (including Shanghai, Yunnan, Inner Mongolia, Beijing, Jilin, Sichuan, Tianjin, Ningxia, Anhui, Shandong, Shanxi, Guangdong, Guangxi, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Hebei, Henan, Zhejiang, Hubei, Hunan, Gansu, Fujian, Guizhou, Liaoning, Chongqing, Shaanxi, Qinghai, and Heilongjiang) and comprised a sample of 11,905 males and 13,464 females aged 18 years and above.

3.2. Variables

The dependent variable in this study is SWB, which reflects respondents’ subjective evaluation of their life. In the CGSS, the indicator is determined by asking respondents “generally speaking, do you think your life is happy or not?” [97,98]. The answers are set to an ordered variable of 1–5, that is, very unhappy = 1 to very happy = 5.

As for the independent variable, in contemporary China, the two most popular mobile payment tools are WeChat (Tencent) and Alipay (Alibaba). For instance, in the third quarter of 2023, the total transaction volume of Alipay and WeChat pay accounted for more than 94% of the total mobile payment market in China [99]. Consequently, we adopt whether respondents use Alipay or WeChat payment as the proxy variable of mobile payment, which is 1 if they had used them and 0 otherwise. Learning from prior SWB research [97,100,101,102], this paper adds a series of covariates to consider the effects of demographic and socio-economic factors on SWB. These variables are gender, age, age-squared/100, ethnicity, political belief, household registration, marital status, education status, income, work status, social security, housing condition, and the household size. Additionally, we also add a series of provincial dummies to control for macro factors. Finally, a total of 18,726 samples are obtained for baseline analysis in our study (11,595 in 2017 and 7131 in 2018).

Table 1 presents the summary statistics of the main variables. It can be concluded that the average SWB in our sample is 3.888 (higher than the median value). In addition, 54.1% of the respondents use mobile payment, 70.2% of the sample are urban residents, and 76.6% of the respondents are married. In our sample, more than half of the respondents had less than a high school education.

Table 1.

Variable definition and descriptive statistics.

Table 2 presents the average SWBs for the mobile payment users and non-users, respectively. The results reveal that the average SWB of those who did not use mobile payments was 3.832, lower than their counterparts (3.937). Analogously, this difference also existed in the subdivided population, except for high-income groups. For example, the average SWB for mobile payment users in urban areas was 3.941, which is 0.053 points greater than that of non-users. For high-income groups, the SWB of mobile payment users was lower than that of their counterparts, possibly because mobile payment has a greater impact on the SWB of low-income groups (we will further confirm this later).

Table 2.

Average SWB for mobile payment users and non-users.

3.3. Estimation Method

In prior works, both the ordinary least squares (OLS) and ordered probit (ordered logit) methods have been used to estimate the effect of socio-economic factors on individuals’ SWB [55,97,103,104]. In general, the estimators under the two methods are basically consistent. Consequently, this study employs the OLS method to perform basic regressions. However, endogeneity is a common problem existing in ICT and SWB literature. Concretely, this may be caused by some unobservable factors affecting both mobile payment and SWB in our study, such as their personal preferences and past experiences. With that in mind, we further adopt the instrumental variable (IV) method to identify the causal association by performing the two-stage least squares (2SLS) estimation [105,106], as shown in Equations (1) and (2).

where SWB and mobile_payment are the dependent variable and the core explanatory variable, respectively. The matrix X represents the control variables. Parameters and are constants, while and are error terms. Equation (1) is the first-stage regression exploring the correlation between mobile payment and IV. Equation (2) is the second-stage regression, where SWB is the dependent variable, and the independent variable is the fitting value of mobile payment obtained by the first-stage regression [31].

In general, a qualified instrumental variable should satisfy the following two requirements: first, it has correlation with the mobile payment; second, it is independent of the disturbance term, also known as the exclusion restriction. Inspired by ICT literature [31,107,108], this paper mainly adopts the condition of people using mobile payment as its instrumental variable. Specifically, we use whether the respondent has a mobile phone and whether the respondent’s family has accessed the Internet in the last six months as proxies for instrumental variables, denoted by “phone” and “Internet”, respectively. Access to mobile devices and the Internet is the premise of using mobile payment. Nevertheless, the above two factors usually do not directly affect an individual’s SWB. They mainly influence the quality of people’s life and life satisfaction by applying them to their daily activities, such as mobile payment and online shopping. Furthermore, Hansen and weak identification tests are performed to ensure the validity of the instrumental variables.

3.4. Mechanism Model

Based on the theoretical framework of the economic–social–environmental perspective, this paper further constructs the following several models to examine the connection mechanism between mobile payment and SWB: first, as for the income effect, Equation (3) is used to determine whether mobile payment can influence an individual’s income. In Equation (4), we add the interaction term between mobile payment and income into the SWB model to depict the heterogeneous effects for people with different income statuses.

Second, to examine how mobile payment affects SWB via the consumption effect and capacity effect, the following mediating effect model is constructed:

where represents the mediating variable reflecting the consumption effect and capacity effect. Accordingly, we adopt the per capita consumption expenditure to measure the consumption effect (including offline and online consumption). As for the capacity effect variable, it is obtained through the question: “do you agree that the Internet allows more people to have access to social resources?” (denoted by RA). The responses ranged from “strongly disagree = 1” to “strongly agree = 5”. The purpose of Equation (5) is to estimate the influence of mobile payment on the mediating variable, while Equation (6) tests the role of the mediating variable in the association between mobile payment and SWB.

Third, we utilize Equation (7) to investigate whether mobile payment affects the relationship between environment quality and SWB. is respondents’ subjective evaluation of their environment quality, measured by asking respondents whether they agree that they are satisfied with the quality of the natural environment around them. The answers are set as an ordered variable with “strongly disagree = 1”, “disagree = 2”, “slightly diagree = 3”, “slightly agree = 4”, “agree = 5”, and “strongly agree = 6”.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Basic Results

We first present the results under OLS estimation, as shown in columns (1)–(4) of Table 3. It can be found that the coefficient of mobile payment in all columns is positive and statistically significant. Columns (5) and (6) further give the results under the ordered probit model. Analogously, mobile payment is still significantly and positively correlated with SWB. To be specific, column (6) reveals that using mobile payment would increase the probability of people feeling very happy by 2.07%.

Table 3.

Mobile payment and SWB: basic results.

As for the control variable, the results attest that the following factors are significantly and positively correlated with individual SWB: political belief, marriage, education, income, social security, housing condition, and household size. There is a U-shaped relationship between age and SWB in our study, suggesting that the SWB of the middle-aged population is lower than that of the younger and older populations [97]. Moreover, we find that gender and ethnicity are significantly negatively correlated with SWB, indicating that women and ethnic minorities have higher levels of SWB. These findings are basically consistent with the mainstream SWB research [70,97,109,110,111]. However, work status and household registration have not been proved to be significantly related to SWB in this research.

4.2. Robustness Checks

In order to ensure the reliability of the above conclusions, the following tests are further conducted in this paper.

First, we reconstruct the core explanatory variable according to the type of mobile application, including whether they used Alipay for mobile payment (Alipay) and whether they used WeChat for mobile payment (WeChat). The two indicators are binary variables, that is, 1 if used and 0 otherwise. The results in Table 4 indicate that both of the two mobile payment methods have a significant positive correlation with individual SWB.

Table 4.

Mobile payment and SWB: replacing the core explanatory variable.

Second, we change the proxy variable of SWB as follows: (1) It is replaced by respondents’ ratings on their own well-being. This indicator is a positive indicator, ranging from 0 to 10; (2) This paper employs the subjective health and subjective depression as the dependent variable, respectively. The two indicators are similar to SWB and have been proven to be closely related to SWB in prior works [112,113]. Both subjective health and subjective depression are set as an ordered variable. Accordingly, subjective health is measured by respondents’ evaluation of their current physical health status with “very unhealthy = 1” and “very healthy = 5”. Subjective depression is obtained by the question: “how often have you felt depressed in the past four weeks?”. The respondent’s answer is assigned as “always = 1”, “often = 2”, “sometimes = 3”, “seldom = 4”, or “never = 5”. As shown in Table 5, it is suggested that mobile payment still has a significant positive impact on each proxy for SWB.

Table 5.

Mobile payment and SWB: replacing the dependent variables.

Third, as aforementioned, IV estimation is further utilized to consider the endogenous problem, and the results are reported in Table 6. The first-stage regression suggests that both of the two IVs are significantly and positively correlated with mobile payment. The F test and Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic indicate that “phone” and “Internet” are not the weak IVs. The second-stage regression shows that the effect of mobile payment on SWB is still significantly positive. Additionally, the Hausman test proves that mobile payment is an endogenous variable, and the Hansen test illustrates that IVs satisfy the exclusion restriction. In general, the basic conclusion of this paper is still robust when using the substitution variable method and the IV regression. Moreover, we find that the coefficient of mobile payment estimated by IV is significantly larger than the OLS estimation, indicating that if the endogeneity of mobile payment is not considered, we may underestimate its impact on SWB.

Table 6.

Mobile payment and SWB: IV estimation.

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

4.3.1. Economics Aspect: Income Effect and Consumption Channel

Column (1) of Table 7 reports the income effect of mobile payment, while column (2) introduces the interaction between mobile payment and income into the SWB model. We observe that mobile payment can significantly improve people’s income level. Moreover, the coefficient of mobile payment is significantly positive in column (2), while its interaction with income is significantly negative. Consequently, the above regression results illustrate that the mechanism of mobile payment stimulating an individual’s SWB via income is reflected in two aspects, namely, mobile payment can not only improve SWB by increasing people’s income, but also has a greater promoting effect on the SWB of the low-income population.

Table 7.

Mobile payment and SWB: income channel (IV estimation).

In Table 8, columns (1)–(3) explore the influence of mobile payment on people’s total consumption expenditure, offline consumption expenditure, and online consumption expenditure, respectively. Meanwhile, columns (4)–(6) estimate the mediating effect of the above three categories of consumption between mobile payment and SWB, respectively. The results in the consumption models suggest that mobile payment can only significantly increase individual online consumption expenditure, but it has no impact on total consumption expenditure and offline consumption expenditure. In other words, the impact of mobile payments on people’s consumption is reflected in the transfer of consumption activities from offline to online. Nevertheless, columns (5) and (6) show that offline consumption expenditure has a significant facilitating effect on SWB, while online consumption expenditure has a significant negative influence on SWB. Therefore, it indicates that although mobile payment can stimulate people’s online consumption, it does not lead to an increase in their SWB.

Table 8.

Mobile payment and SWB: consumption channel (IV estimation).

4.3.2. Social Aspect: Capacity Effect

Table 9 presents the results to determine whether mobile payment can improve people’s SWB via the capacity effect. In column (1), the coefficient of mobile payment is found to be significantly positive, proving that mobile payment is conducive to allowing more people to obtain access to social resources. Meanwhile, in column (2), the capacity effect variable is significantly and positively correlated with SWB. Consequently, the results reveal that mobile payment can increase an individual’s SWB via improving their perception of their capacity to access social resources.

Table 9.

Mobile payment and SWB: capacity effect (IV estimation).

4.3.3. Environmental Effect

The estimation results of Equation (7) are presented in Table 10. It is observed that the coefficients for both environment quality and mobile payment are significantly positive. However, the coefficient for their interaction term is negative, with statistical significance at the 1% level. These findings suggest that in regions characterized by poorer environmental quality, mobile payment exhibits a more pronounced positive influence on individual SWB. Consequently, the widespread adoption of mobile payment has important practical implications for mitigating the adverse effects of ecological degradation on public welfare.

Table 10.

Mobile payment and SWB: environmental effect (IV estimation).

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis: Regional Differences

Considering that there are considerable differences in regional development within China [114,115], we further divide the sample into two parts: eastern China and central and western China. In general, residents of eastern China face more convenient living conditions than those in central and western China, such as developed financial, commercial, and logistics services. Meanwhile, the eastern region also has relatively better air quality. For the central and western regions, due to the relatively less-developed business and infrastructure, people suffer greater commuting costs (time and distance) and may be more exposed to the potential impact of environmental pollution when conducting transaction activities. Therefore, the promotion effect of mobile payment on SWB for residents in central and western China may be more obvious because they are facing greater resource constraints and are more likely to be affected by environmental pollution when participating in offline activities.

As shown in Table 11, we find that mobile payment is conducive to promoting the SWB of residents in both central and western China and eastern China, while it has a relatively larger facilitating effect in central and western China. Consequently, the finding reveals that mobile payments have a greater promoting effect on SWB for people from underdeveloped areas within the economic–social–environmental framework.

Table 11.

Mobile payment and SWB: regional differences (IV estimation).

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This study introduces an economic–social–environmental perspective to explore the association between mobile payment and SWB. We extend the mobile payment–SWB literature by not only considering how mobile payment affects the economic and social determinants of SWB, but also analyzing how it alters the relationship between the external environment quality and SWB. Accordingly, using data from the CGSS2017 and CGSS2018, we find that mobile payment can significantly increase Chinese residents’ SWB. The results are still robust when adopting the substitution variable method and conducting IV estimation. The findings are in line with two categories of the literature. The first category is the research that emphasizes the positive effect of Internet use on personal well-being [62,64,116], while the second category finds the importance of financial technology or Internet finance to improve public welfare [117,118,119].

The results further prove that the positive association is a composite influence from multiple channels. Firstly, it shows that mobile payment can boost an individual’s income to improve their SWB and has a greater impact on the SWB of low-income groups. Moreover, as for the social aspect, we also find that the application of mobile payment is conducive to providing people with more equitable access to social resources. The results further support the finding in Table 2, suggesting that the new transaction method of mobile payment brings opportunities to improve the welfare of vulnerable groups and help eliminate welfare inequality. The conclusion is also consistent with a growing body of literature underscoring the role of information technology in reducing poverty and inequality [120,121,122]. However, our study shows that mobile payment can promote online consumption, but it does not lead to an increase in individuals’ SWB. As suggested by Ahn and Nam [83], mobile payment may increase the risk of overconsumption and have a negative impact on consumers. Secondly, our study proves that the popularity of mobile payment is beneficial for reducing the negative impact of environmental pollution on individuals’ SWB. A growing body of research shows that environmental pollution exposure reduces people’s well-being [123,124]. Therefore, our findings provide some empirical evidence for how to reduce the negative impact of environmental pollution on individuals’ SWB via digital technology.

In addition, the disaggregated analysis demonstrates that mobile payment has a stronger positive impact on the SWB of people in areas that are relatively disadvantaged in the economic–socio–environmental system. The possible reason is that residents in these areas may face more serious resource constraints and environmental pollution problems, so mobile payment has a more positive role in improving their quality of life. Zhang et al. [31], for instance, found that mobile payment has a greater positive impact on household consumption expenditure in central and western China than that in eastern China. They hold that the main reason for this is that households in eastern China face more developed financial and business services, and mobile payment is more of an alternative to traditional payment methods for them. In addition, Shao et al. [125] suggested that people with better economic and social conditions have more ability to reduce the negative impact of environmental pollution on themselves. As the Brundtland Report asserted, “sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [126]. Therefore, our conclusion proves that the adoption of mobile payment can contribute to sustainable development and a fairer and happier world.

6. Policy Implications and Limitations

Our work offers several implications for implementing people-oriented development policies. The goal of sustainable development requires achieving a dynamic balance between the economy, society, and the environment, thereby improving public well-being. The findings in our study underscore the potential of fintech to promote sustainable development by improving people’s economic and social conditions as well as coordinating the relationship between the natural environment and human activities. As the world’s largest developing country, China has witnessed the tremendous development and application of Internet technology during the past few decades. A series of information promotion policies has been promulgated and implemented to increase China’s digital technology penetration and its application. For instance, the Chinese government issued a white paper entitled “the State of the Internet in China” in 2010, which introduced the development of the Internet in China and elaborated the Chinese government’s policies on the Internet and its basic views on relevant issues. Subsequently, the State Council of the People’s Republic of China released the “guiding opinions” to promote the “Internet plus” action in 2015. The initiative aims to promote productivity and creativity in the economic and social system by deepening the integration of the Internet in various fields in China. Additionally, the Chinese government has also proposed the development strategies of “digital China” and the “digital village” in recent years, thus promoting its modernization process. Therefore, China’s experience indicates that taking effective measures to improve the application of digital technology can accelerate the modernization process in developing countries. These measures could involve increasing investments in information infrastructure, improving citizens’ information literacy, and promoting the integration of the Internet and social systems. At the same time, our study suggests that developing countries should take effective measures to amplify the positive impact of online consumption on public well-being and reduce its negative impact. For example, strengthening the quality supervision of online products and improving the logistics system and after-sales service guarantee all contribute to enhancing people’s good consumption experience. In addition, policymakers need to take more measures to analyze the deep-seated reasons that limit citizens’ use of mobile payment technology, especially the socially vulnerable population, thereby formulating more accurate information policies.

This paper is subject to several limitations. First, although we employ the IV estimator to address the endogeneity issue, the material used in our study is two years of cross-sectional data, not panel data. This makes it difficult to determine the long-term and dynamic impact of mobile payment on individual SWB. Furthermore, additional studies can select a more appropriate IV to identify causality. Second, although this paper offers an economic–social–environmental perspective to understand how mobile payment affects individual SWB, it does not further investigate how mobile payment specifically influences each pathway, for example, how mobile payment can reduce the negative impact of environmental pollution on people’s SWB. Is there heterogeneity for this? Moreover, the study does not discuss the potential confounding variables that may affect the relationship between mobile payment and SWB, such as an individual’s economic and social status and household endowment. Third, the mobile payment indicator used in this paper is a dummy variable, which does not allow for the observation of the influence of individual differences in mobile payment usage on SWB, such as mobile payment usage intensity or usage in different scenarios. Further work can adopt more specific data to capture that information. Fourth, as aforementioned, the experience of mobile payment in China in improving public welfare may offer several lessons for other developing countries. To address this issue, the research needs to further explore the institutional, cultural, and economic factors that promote the popularity of mobile payment in China. Meanwhile, analyzing the effect of mobile payment on the economic–social–environmental system of other countries, such as India and African countries, is also critical in order to conduct sustainable development. Finally, an over-reliance on digital technology may also increase people’s risk of social anxiety and obesity due to long hours indoors and a lack of exercise [127]. Therefore, although mobile payment may reduce the negative impact of environmental pollution on people’s SWB, it may also have a negative impact on SWB due to the lack of connection with the external social environment, which is worth discussing in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G. and J.Z.; Methodology, X.G. and J.Z.; Validation, X.G., H.Z. and J.Z.; Formal analysis, X.G. and H.Z.; Data curation, J.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.G. and J.Z.; Supervision, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers: 18BJY108), the Chinese Ministry of Education Youth Fund Project (Grant numbers: 23YJC630228), the 2022 Shanghai Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (Grant numbers: 2022ZJB007); the Shanghai Pujiang Program (Grant numbers: 22PJC042), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grant numbers: 2023ECNU-YYJ040).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Diener, E.; Oishi, S.; Tay, L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longstreet, P.; Brooks, S. Life satisfaction: A key to managing internet & social media addiction. Technol. Soc. 2017, 50, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Krueger, A.B. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J. Econ. Perspect. 2006, 20, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. The utility of happiness. Soc. Indic. Res. 1988, 20, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on 28 June 2012. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/734076?v=pdf (accessed on 12 May 2024).

- Agarwal, S.; Qian, W.; Tan, R. Financial inclusion and financial technology. In Household Finance; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.W.; Yu, J.S.; Hassan, M.K. Financial inclusion and economic growth in OIC countries. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2018, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneeza, A.; Arshad, N.A.; Arifin, A.T. The application of blockchain technology in crowdfunding: Towards financial inclusion via technology. Int. J. Manag. Appl. Res. 2018, 5, 82–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, A.B. Mobile technology and financial inclusion. In Handbook of Blockchain, Digital Finance, and Inclusion; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Impact of digital finance on financial inclusion and stability. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2018, 18, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, S.A.; Odongo, T.M.; Were, M. Mobile financial services and financial inclusion: Is it a boon for savings mobilization? Rev. Dev. Financ. 2017, 7, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, K. Mobile money for financial inclusion. Inf. Commun. Dev. 2012, 61, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Gamboa, J.; Cabrera-Barona, P.; Jácome-Estrella, H. Financial inclusion and multidimensional poverty in Ecuador: A spatial approach. World Dev. Perspect. 2021, 22, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajefu, J.B.; Demir, A.; Haghpanahan, H. The impact of financial inclusion on mental health. SSM-Popul. Health 2020, 11, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaime, S.; Gaysset, I. Financial inclusion and stability in MENA: Evidence from poverty and inequality. Financ. Res. Lett. 2018, 24, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Zoo, H.; Lee, H.; Kang, J. Mobile financial services, financial inclusion, and development: A systematic review of academic literature. Electron. J. Inf. Syst. Dev. Ctries. 2018, 84, e12044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, D.; Acharya, D. Financial inclusion and economic growth linkage: Some cross country evidence. J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2018, 10, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babajide, A.A.; Adegboye, F.B.; Omankhanlen, A.E. Financial inclusion and economic growth in Nigeria. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2015, 5, 629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.Y.; Mercado, R. Financial inclusion, poverty, and income inequality in developing Asia. Asian Dev. Bank Econ. Work. Pap. Ser. 2015, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daragmeh, A.; Lentner, C.; Sági, J. FinTech payments in the era of COVID-19: Factors influencing behavioral intentions of “Generation X” in Hungary to use mobile payment. J. Behav. Exp. Financ. 2021, 32, 100574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GSMA. The State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2024. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/sotir/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GSMA-SOTIR-2024_Report_v7-2.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Liu, Z.; Ben, S.; Zhang, R. Factors affecting consumers’ mobile payment behavior: A meta-analysis. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 19, 575–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Luna, I.R.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Munoz-Leiva, F. Mobile payment is not all the same: The adoption of mobile payment systems depending on the technology applied. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.L.; Lee, Y.C. Examining the influencing factors of third-party mobile payment adoption: A comparative study of Alipay and WeChat Pay. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 247–284. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.; Mirusmonov, M.; Lee, I. An empirical examination of factors influencing the intention to use mobile payment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 310–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurazo, J.; Vega, M. Why people use digital payments: Evidence from micro data in Peru. Lat. Am. J. Cent. Bank. 2021, 2, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.J. Understanding medical consumers’ intentions to switch from cash payment to medical mobile payment: A perspective of technology migration. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallat, N. Exploring consumer adoption of mobile payments–A qualitative study. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2007, 16, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Vatsa, P.; Ma, W.; Zheng, H. Does mobile payment adoption really increase online shopping expenditure in China: A gender-differential analysis. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 77, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Wu, Y.; Guo, J. Mobile payment and Chinese rural household consumption. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 71, 101719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Gong, X. Mobile payment and rural household consumption: Evidence from China. Telecommun. Policy 2022, 46, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, J.; Maier, E.; Wilken, R. The effect of credit card versus mobile payment on convenience and consumers’ willingness to pay. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, J.J. The impact of digital finance on household consumption: Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2020, 86, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Ma, W. Scan the QR code of happiness: Can mobile payment adoption make people happier? Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 2299–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, C.; Guo, J. Mobile payment and subjective well-being in rural China. Econ. Res. -Ekon. Istraz. 2023, 36, 2215–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, X.; Yan, J. The effect of digital finance on residents’ happiness: The case of mobile payments in China. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 24, 69–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNNIC. The 53rd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development. Available online: https://www.199it.com/archives/1682273.html (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- Easterlin, R.A. Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In Nations and Households in Economic Growth; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Prakash, K.; Smyth, R.; Wang, H. Housing wealth and happiness in urban China. Cities 2020, 96, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; King, S.P.; Smyth, R.; Wang, H. Housing property rights and subjective wellbeing in urban China. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2016, 45, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powdthavee, N. How much does money really matter? Estimating the causal effects of income on happiness. Empir. Econ. 2010, 39, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, M.D.; Galiani, S.; Gertler, P.J.; Martinez, S.; Titiunik, R. Housing, health, and happiness. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2009, 1, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Chernova, K. Absolute income, relative income, and happiness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 88, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. Econ. J. 2001, 111, 465–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Geng, L.; Zhou, K. Environmental pollution, income growth, and subjective well-being: Regional and individual evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 34211–34222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhou, T. Effects of objective and subjective environmental pollution on well-being in urban China: A structural equation model approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 249, 112859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Shin, K.; Managi, S. Subjective well-being and environmental quality: The impact of air pollution and green coverage in China. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 153, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehdanz, K.; Maddison, D. Local environmental quality and life-satisfaction in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.Y.; Hahn, Y. Work transitions, gender, and subjective well-being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 16, 2085–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Carrasco, M.; Casas, F.; Malo, S.; Viñas, F.; Dinisman, T. Changes with age in subjective well-being through the adolescent years: Differences by gender. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisenberg, G.; Woodley, M.A. Gender differences in subjective well-being and their relationships with gender equality. J. Happiness Stud. 2015, 16, 1539–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, M. Hukou changes and subjective well-being in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, I.; Smyth, R.; Liu, Y. The moderating effects of demographic factors and hukou status on the job satisfaction–subjective well-being relationship in urban China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 1333–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C.; Dreher, A.; Fischer, J.A. Formal institutions and subjective well-being: Revisiting the cross-country evidence. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2010, 26, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, M.; Yu, N. Internet use and lower life satisfaction: The mediating effect of environmental quality perception. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 176, 106725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, J.; Plagnol, A.C.; Corr, P.J. Subjective well-being and social media use: Do personality traits moderate the impact of social comparison on Facebook? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, V. Social comparison and subjective well-being: Does the health of others matter? Bull. Econ. Res. 2012, 64, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gong, X.; Zhang, H. ICT diffusion and health outcome: Effects and transmission channels. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 67, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.; Li, X. Smartphones and psychological well-being in China: Examining direct and indirect relationships through social support and relationship satisfaction. Telemat. Inform. 2020, 54, 101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellacci, F.; Viñas-Bardolet, C. Internet use and job satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 90, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H. How does time spent on WeChat bolster subjective well-being through social integration and social capital? Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 2147–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Chun, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, J. Internet use and well-being in older adults. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2015, 18, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierewan, A.C.; Tampubolon, G. Internet use and well-being before and during the crisis in Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 119, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotten, S.R.; Ford, G.; Ford, S.; Hale, T.M. Internet use and depression among older adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, H.; Bibby, P.A. Personality, fear of missing out and problematic internet use and their relationship to subjective well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Internet use and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Aa, N.; Overbeek, G.; Engels, R.C.; Scholte, R.H.; Meerkerk, G.J.; Van den Eijnden, R.J. Daily and compulsive internet use and well-being in adolescence: A diathesis-stress model based on big five personality traits. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, E.F.; Juvonen, J.; Gable, S.L. Internet use and well-being in adolescence. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 58, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellacci, F.; Tveito, V. Internet use and well-being: A survey and a theoretical framework. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Sousa-Poza, A.; Nimrod, G. Internet use and subjective well-being in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 132, 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.F.; Juang, L.P.; Syed, M. Internet use and well-being among college students: Beyond frequency of use. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2007, 48, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Madaleno, M.; Taskin, D. Financial inclusion and poverty: Evidence from Turkish household survey data. Appl. Econ. 2022, 54, 2135–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, S.A.; Marisetty, V.B. Financial inclusion and poverty: A tale of forty-five thousand households. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 1777–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomson, I.; Villano, R.A.; Hadley, D. Effect of financial inclusion on poverty and vulnerability to poverty: Evidence using a multidimensional measure of financial inclusion. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 613–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.A.; Inaba, K. Does financial inclusion reduce poverty and income inequality in developing countries? A panel data analysis. J. Econ. Struct. 2020, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T. Financial inclusion and poverty reduction in India. J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2019, 11, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, N.; Blair, J.; Dettling, L. The smart money is in cash? Financial literacy and liquid savings among US families. J. Account. Public Policy 2023, 42, 107000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupák, A.; Fessler, P.; Hsu, J.W.; Paradowski, P.R. Investor confidence and high financial literacy jointly shape investments in risky assets. Econ. Model. 2022, 116, 106033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Financial permeation and rural poverty reduction Nexus: Further insights from counties in China. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 76, 101863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Q.; Wei, X. Financial literacy, household portfolio choice and investment return. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2020, 62, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.H.; Yang, L.L. Mobile payment and online to offline retail business models. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, M.B. Consumption with liquidity constraints: An analytical characterization. Econ. Lett. 2018, 167, 40–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.Y.; Nam, Y. Does mobile payment use lead to overspending? The moderating role of financial knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 134, 107319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.K. Human rights and capabilities. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.K. Preface. In Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach: Theoretical Insights and Empirical Applications; Kuklys, W., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A.K. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A.K. Inequality Reexamined; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S.; Akobeng, E. ICT, governance and inequality in Africa. Telecommun. Policy 2021, 45, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, R.; Bruneau, C. Microfinance, financial inclusion and ICT: Implications for poverty and inequality. Technol. Soc. 2019, 59, 101154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Chen, L.; Fan, Y.; Liu, M.; Jiang, F. Effect of ambient air quality on subjective well-being among Chinese working adults. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, C.M.; Utomo, A. Evaluating the association between urban green spaces and subjective well-being in Mexico city during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Place 2021, 70, 102606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awan, T.M.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z. Does media usage affect pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors? Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2022, 82, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Yu, M. Scale of cities and social trust: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 76, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, M.; Mei, R.; Wang, F. Internet use and individuals’ environmental quality evaluation: Evidence from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 710, 136290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J. Social capital and health in China: Evidence from the Chinese general social survey 2010. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 142, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H. Assessing the effects of haze pollution on subjective well-being based on Chinese General Social Survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadullah, M.N.; Xiao, S.; Yeoh, E. Subjective well-being in China, 2005–2010: The role of relative income, gender, and location. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 48, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Luo, Z. Measurement of relative welfare poverty and its impact on happiness in China: Evidence from CGSS. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 69, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forward the Economist. Insight 2024: Competition Pattern and Market Share of China’s Mobile Payment Industry. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/sotir/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/GSMA-SOTIR-2024_Report_v7-2.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, M.; Xu, Z.; Ye, Y.; Chen, S.; Pan, Y.; Chen, J. The influence of community sports parks on residents’ subjective well-being: A case study of Zhuhai City, China. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; He, L.; Hamilton, J.; Xu, D. Children’s marriage and parental subjective well-being: Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 70, 101705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Sousa-Poza, A. Commute time and subjective well-being in urban China. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 48, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L. Effect of time-varying exposure to air pollution on subjective well-being. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H. Differential associations between volunteering and subjective well-being by labor force status: An investigation of experiential and evaluative well-being using time use data. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 1737–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Microeconometrics Using Stata, Revised ed.; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Billari, F.C.; Giuntella, O.; Stella, L. Does broadband Internet affect fertility? Popul. Stud. 2019, 73, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Duan, Y.; Ward, M.R. The effect of broadband internet on divorce in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 139, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovi, M.; Laamanen, J.P. Income, aspirations and subjective well-being: International evidence. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2021, 185, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, J. Subjective well-being in China: How much does commuting matter? Transportation 2019, 46, 1505–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Lina, S.; Gunatilaka, R. Subjective well-being and its determinants in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2009, 20, 635–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gataūlinas, A.; Banceviča, M. Subjective health and subjective well-being (the case of EU countries). Adv. Appl. Sociol. 2014, 4, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, J.P.; Pinol, N.L.; Uralde, J.H. Poverty, psychological resources and subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 73, 375–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, B. Research on regional differences, spatial aggregation and convergence of China’s digital economy level. J. Stat. Inf. 2024, 39, 63–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ren, B.; He, H. Spatial distribution and characteristics of China’s digital economy development. J. Stat. Inf. 2023, 38, 28–40. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhou, X. Internet use and Chinese older adults’ subjective well-being (SWB): The role of parent-child contact and relationship. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’dri, L.M.; Kakinaka, M. Financial inclusion, mobile money, and individual welfare: The case of Burkina Faso. Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C. Risk identification, future value and credit capitalization: Research on the theory and policy of poverty alleviation by Internet finance. China Financ. Econ. Rev. 2017, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyegera, G.K.; Matsumoto, T. Mobile money, remittances, and household welfare: Panel evidence from rural Uganda. World Dev. 2016, 79, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzator, J.; Acheampong, A.O.; Appiah-Otoo, I.; Dzator, M. Leveraging digital technology for development: Does ICT contribute to poverty reduction? Telecommun. Policy 2023, 47, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djahini-Afawoubo, D.M.; Couchoro, M.K.; Atchi, F.K. Does mobile money contribute to reducing multidimensional poverty? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2023, 187, 122194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, H.; Katz, R.; Valencia, R. The impact of broadband on poverty reduction in rural Ecuador. Telemat. Inform. 2022, 75, 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanduijav, C.; Ferreira, S.; Filipski, M.; Hashida, Y. Air pollution and happiness: Evidence from the coldest capital in the world. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 187, 107085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, D.K.; Padmaja, M.; Dash, A.K. Socioeconomic determinants of happiness: Empirical evidence from developed and developing countries. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2024, 109, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Tian, Z.; Fan, M. Do the rich have stronger willingness to pay for environmental protection? New evidence from a survey in China. World Dev. 2018, 105, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Our common future—Call for action. Environ. Conserv. 1987, 14, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavici, S.; Ayaz-Alkaya, S. Internet addiction, social anxiety and body mass index in adolescents: A predictive correlational design. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2024, 160, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).