Evaluating Arabic Emotion Recognition Task Using ChatGPT Models: A Comparative Analysis between Emotional Stimuli Prompt, Fine-Tuning, and In-Context Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We evaluate ChatGPT (GPT-3.5 Turbo and GPT-4) on the Arabic multi-label emotion classification task using three settings: fine-tuning, the recent EmotionPrompt proposed in [26], and traditional in-context learning.

- Through our empirical analyses, we find that the fine-tuned GPT-3.5 Turbo on Arabic multi-label emotion classification established a new state-of-the-art. It outperformed the base models experimented with few-shot prompting and EmotionPrompt, as well as task-specific models. This finding should motivate future work focused on enhancing this task using LLMs finetuning process.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Emotion Recognition Task and Models of Emotion

- The discrete emotion model, also known as the categorical emotion model, is founded on the concept that a restricted number of universally recognized human emotions exist. This model has found extensive use in research papers concerning emotional classification, primarily owing to its straightforward applicability. Two widely used discrete emotion models are Ekman’s six basic emotions [31] and Plutchik’s emotional wheel model [32], as shown in Figure 1a and Figure 1b, respectively. Ekman’s basic emotion model and its variants [33,34] are widely accepted by the emotion recognition community [35,36]. Six basic emotions typically include “anger”, “disgust”, “fear”, “happiness”, “sadness”, and “surprise”. In contrast, Plutchik’s wheel model [32] involves eight basic emotions (i.e., “joy”, “trust”, “fear”, “surprise”, “sadness”, “anticipation”, “anger”, and “disgust”) and the way how these are related to one another (Figure 1b). For example, joy and sadness are opposites, and anticipation can easily develop into vigilance. This wheel model is also referred to as the componential model, where emotions located nearer to the center of the wheel exhibit greater intensity compared to those situated towards the outer edges.

- The dimensional emotional modelling [29] is grounded in the notion that emotional labels exhibit systematic relationships with one another. Consequently, dimensional models place emotional states within a dimensional space, which can be unidimensional (1-D) or multidimensional (2-D and 3-D), thereby illustrating the relationship between emotional states. The latter model encompasses emotion labels in three key dimensions: “Valence”, “Arousal”, and “Power”. Dimensional models are particularly recommended for projects seeking to highlight similarities among emotional states [37]. The widely used dimensional emotion model is Russell [30] (Figure 1c).

2.2. Related Work

3. Preliminaries

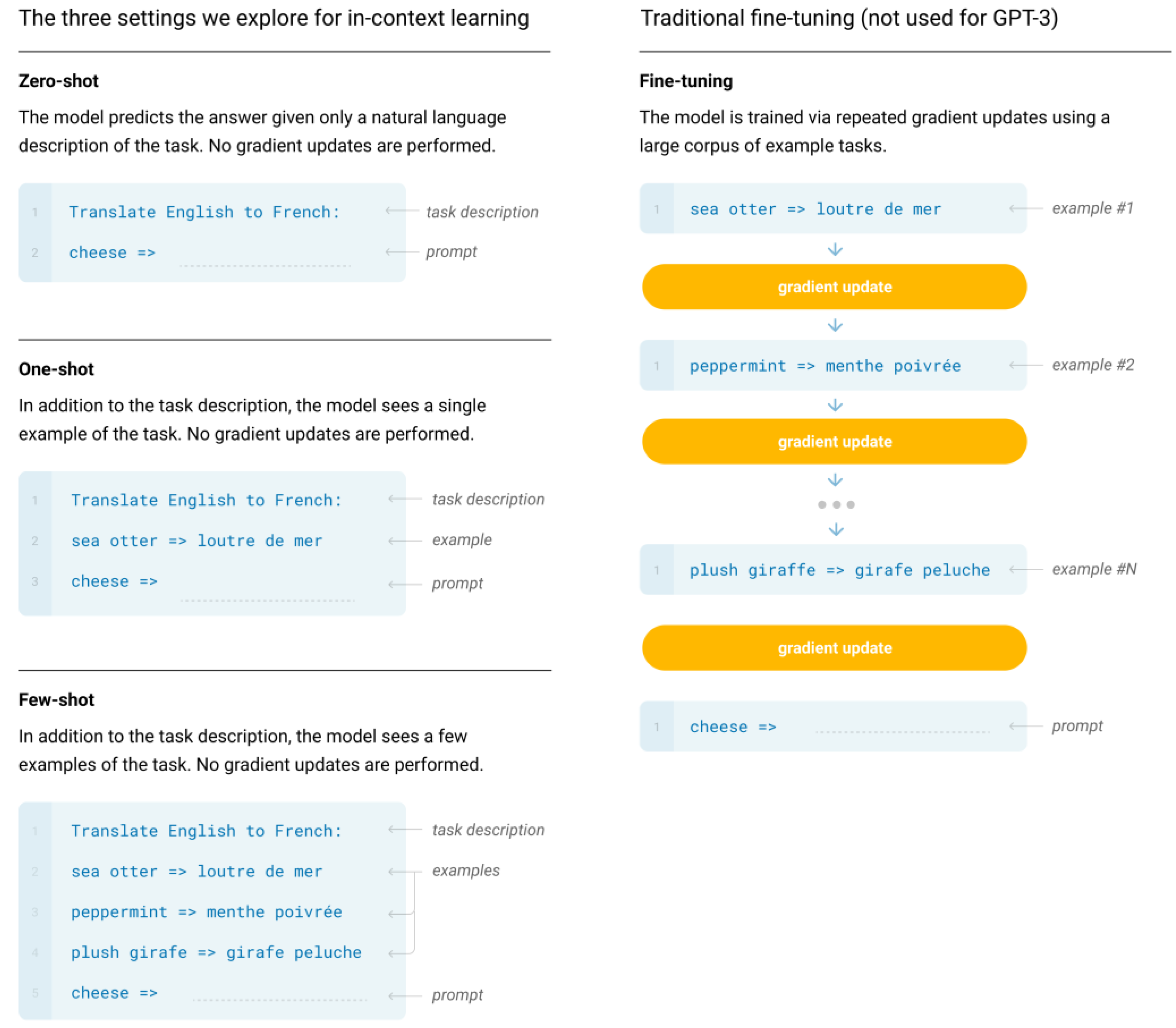

3.1. Large Language Models and In-Context Learning

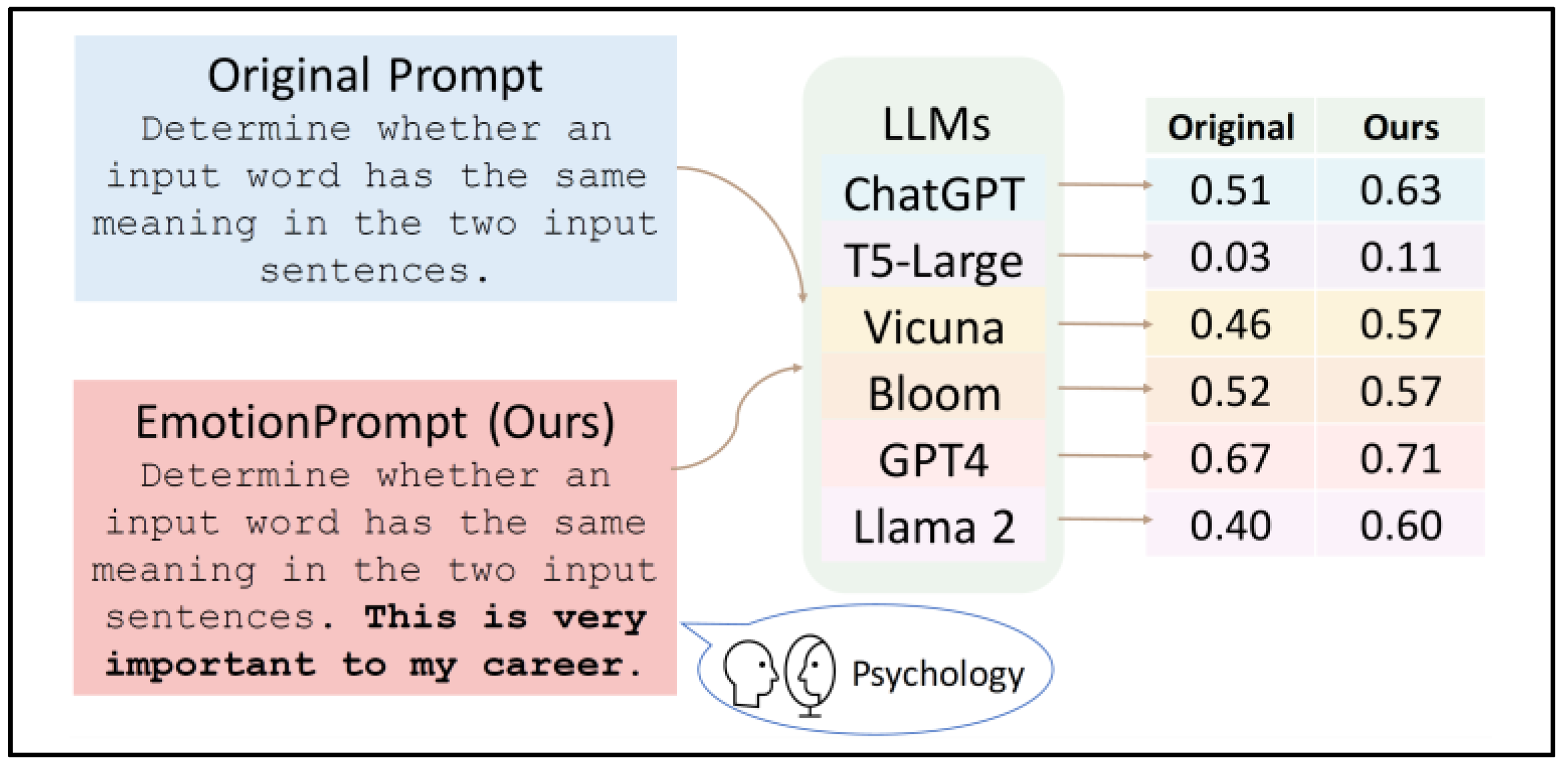

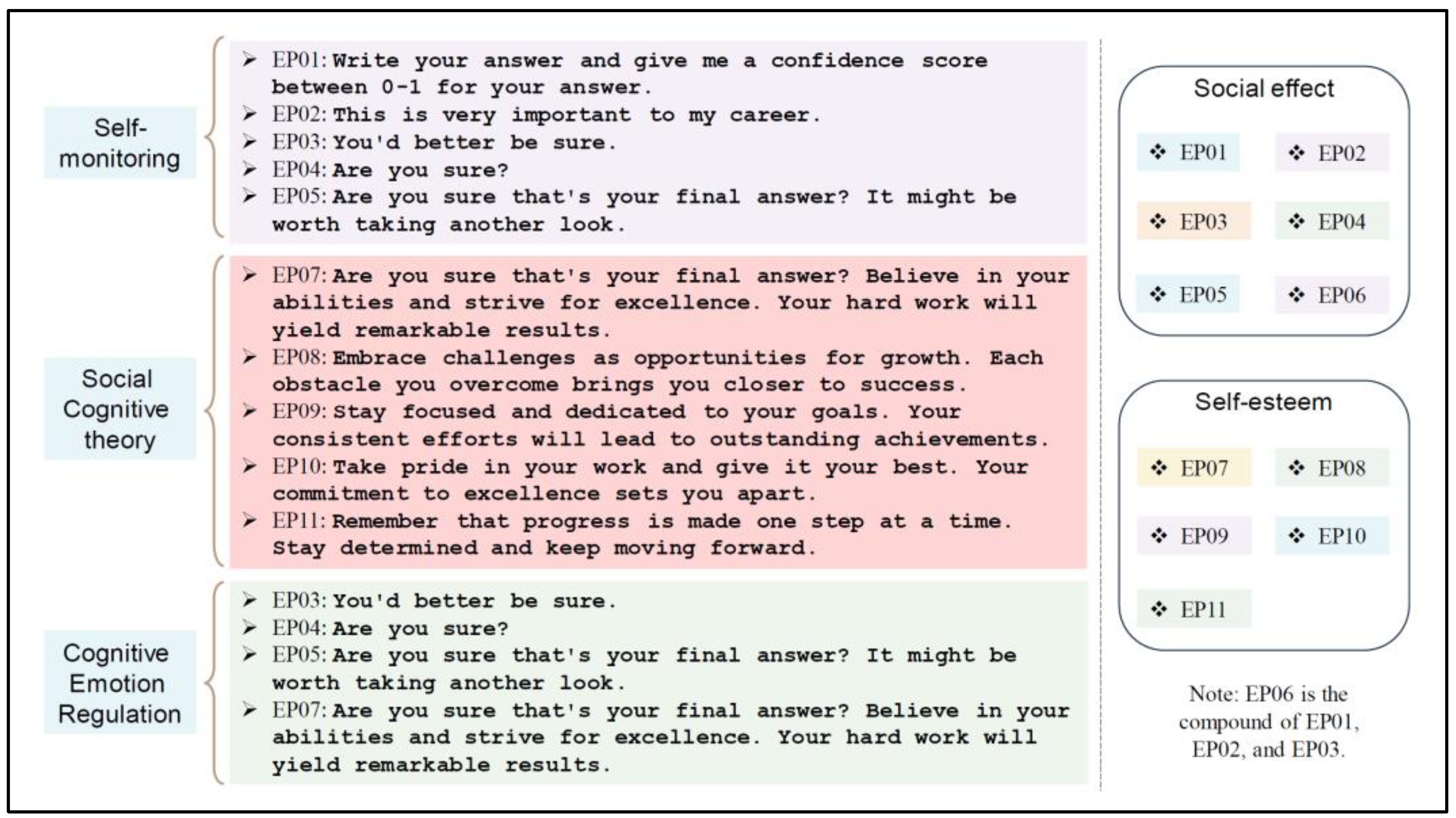

3.2. Emotional Prompts (EmotionPrompt)

3.3. Fine-Tuning

4. Materials and Method

4.1. Models’ Deployment, Fine-Tuning and Predictive Testing

4.2. Data Pre-Processing and Formatting

4.2.1. Dataset

4.2.2. Data Preprocessing: Arabic Tweet Preprocessing

- Punctuation removal: we removed symbols (-, _, ., ,, ;, :, ‘, etc.) that are irrelevant in our proposal.

- Latin characters and digit removal: we excluded numerical and Latin data because they are not effective in categorizing the emotional label within tweets.

- Emoji replacement: we developed a lexicon comprising approximately 100 commonly used emojis on Twitter. Subsequently, we replaced each emoji with its corresponding Arabic word.

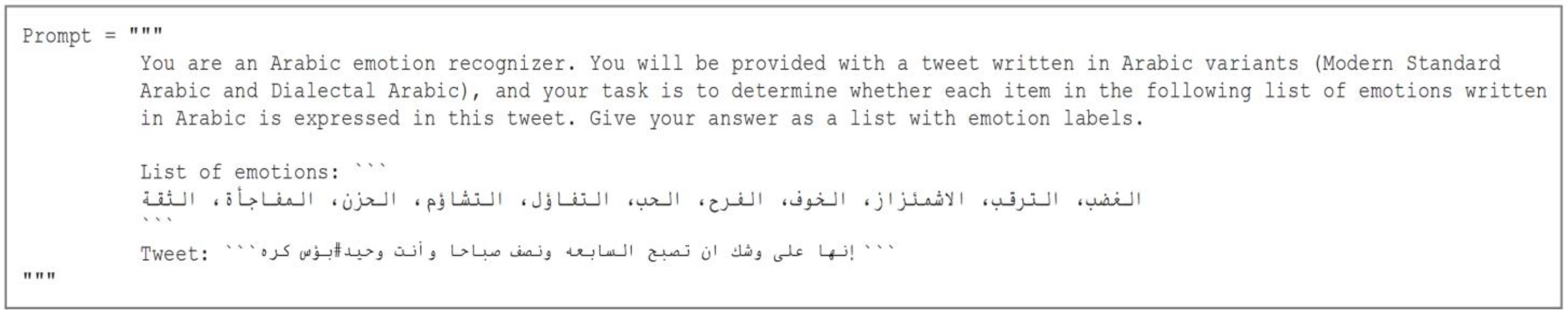

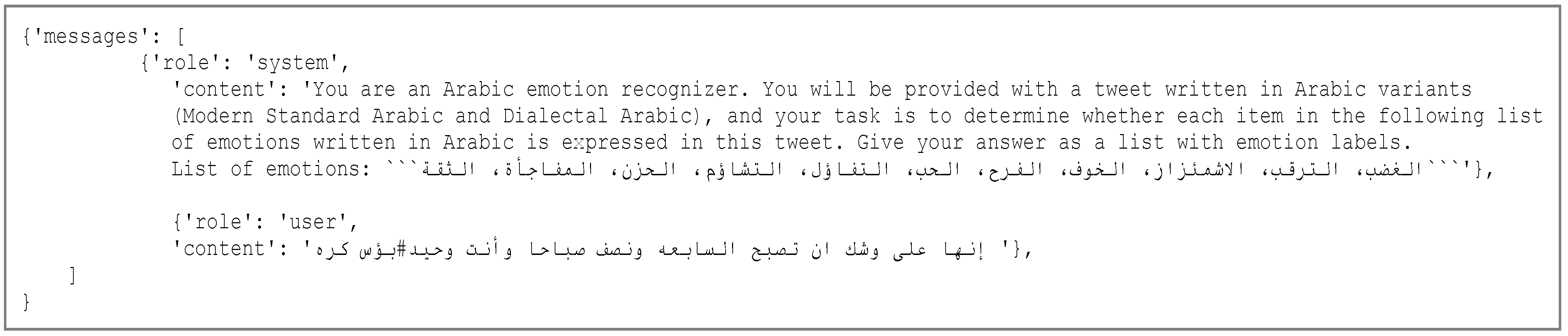

4.3. Prompt Design

4.4. Supervised Fine-Tuning Process

- Data formatting for fine-tuning: Train and validation sets

5. Evaluation

5.1. Evaluation Settings

- temperature = 0: Higher values like 0.8 will make the completions more random, while lower values like 0.2 will make it more focused and deterministic. Since the completion of our emotion recognition task must contain a list of exact labels (emotions), we chose a temperature value equal to 0 to make it more deterministic.

- frequency_penalty = 0 (Defaults to 0): Limits the frequency of tokens in a given response. Positive values penalize new tokens based on their existing frequency in the text so far, decreasing the model’s likelihood of repeating the same line verbatim. In our emotion recognition task, the completion cannot contain more than one occurrence of each label returned.

- presence_penalty = 0 (Defaults to 0): Positive values penalize new tokens based on whether they appear in the text so far, increasing the model’s likelihood of talking about new topics. In our case, we chose the default value, we do not need to force the system to use new tokens and produce new ideas. Our model aims at predicting the emotion labels conveyed in an Arabic tweet among 11 ones (“anger”, “anticipation”, “disgust”, “fear”, “joy”, “love”, “optimism”, “pessimism”, “sadness”, “surprise”, and “trust”).

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

- Example-Based Measures

- Label-based measures

6. Results, Discussion, and Limitations

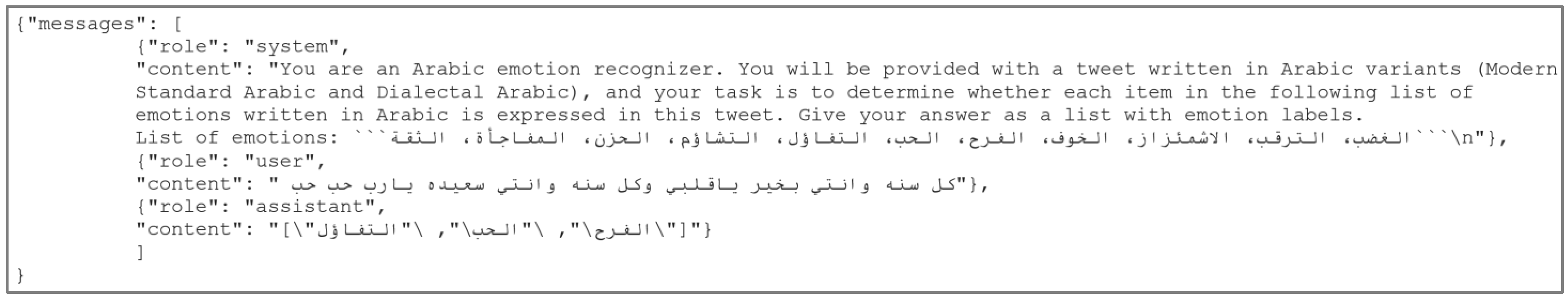

6.1. Analyzing the Fine-Tuned Models

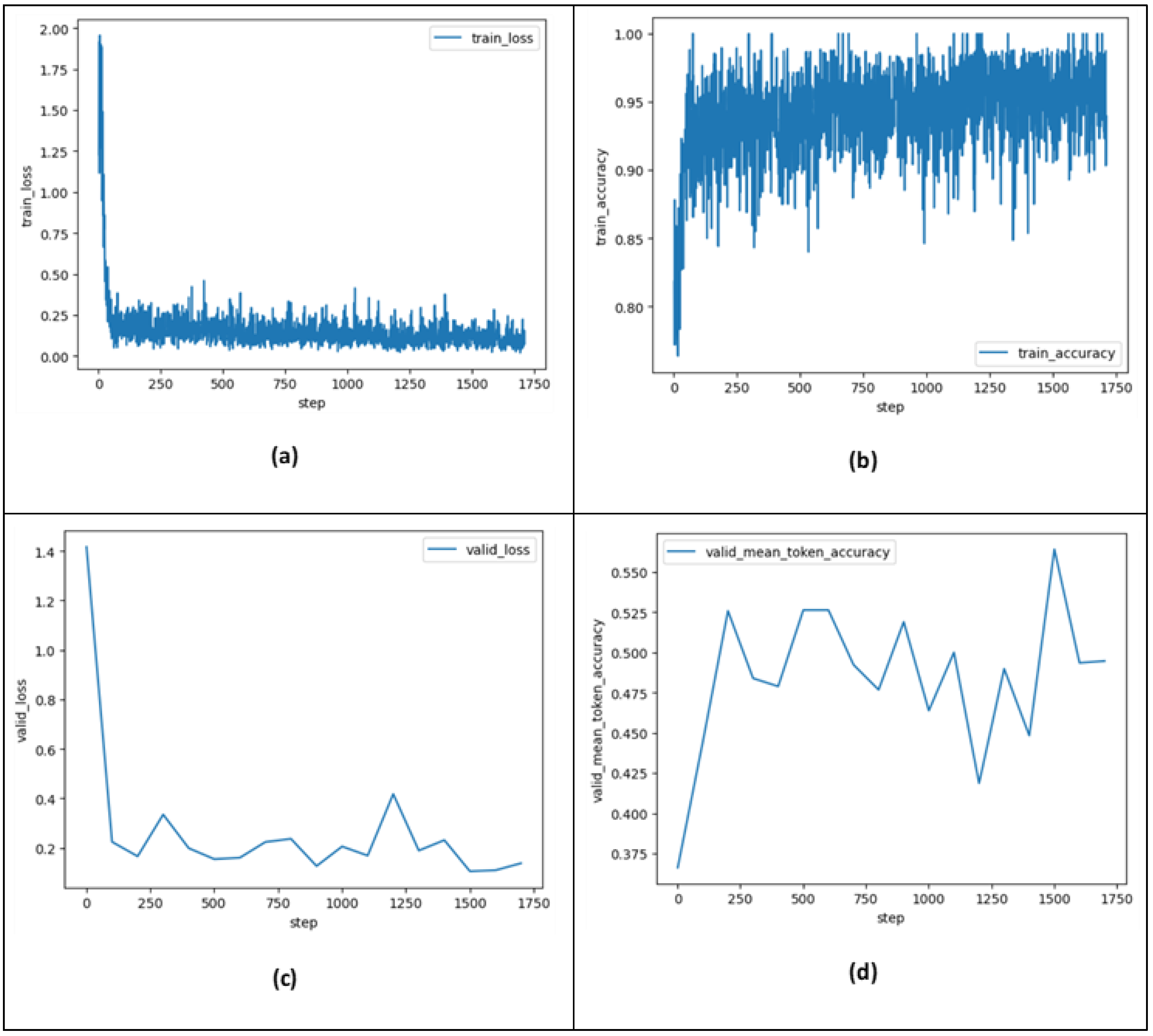

6.2. Comparative Analysis and Models’ Evaluation

6.2.1. Fine-Tuned Models Evaluation and Performance Comparison with the Base Model and SOTA

6.2.2. Models’ Performance Metrics Comparison per Emotional Label

6.3. Limitations

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ekman, P. Facial Expressions of Emotion: New Findings, New Questions; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Cao, L.; Zhou, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Yang, A.; Li, X.; Jia, W.; Yu, S. A survey on deep learning for textual emotion analysis in social networks. Digit. Commun. Networks 2021, 8, 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balazs, J.A.; Velásquez, J.D. Opinion Mining and Information Fusion: A survey. Inf. Fusion 2016, 27, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambria, E. Affective Computing and Sentiment Analysis. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2016, 31, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro-Peláez, J.; Hernández-García, Á.; Urueña-López, A. The Role of Emotions and Trust in Service Recovery in Business-to-Consumer Electronic Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2015, 10, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezoa-Fuentes, C.; García-Rivera, D.; Matamoros-Rojas, S. Sentiment and Emotion on Twitter: The Case of the Global Consumer Electronics Industry. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, F.; Yu, Z. A Two-Stage Nonlinear User Satisfaction Decision Model Based on Online Review Mining: Considering Non-Compensatory and Compensatory Stages. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 19, 272–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poushneh, A.; Vasquez-Parraga, A.Z. Emotional Bonds with Technology: The Impact of Customer Readiness on Upgrade Intention, Brand Loyalty, and Affective Commitment through Mediation Impact of Customer Value. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 14, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudrie, J.; Patil, S.; Kotecha, K.; Matta, N.; Pappas, I. Applying and understanding an advanced, novel deep learning approach: A COVID 19, text based, emotions analysis study. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 23, 1431–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, R.L.; De Silva, M.J.; Silva, D.H.; Ayub, M.S.; Carrillo, D.; Nardelli, P.H.J.; Rodriguez, D.Z. Event Detection System Based on User Behavior Changes in Online Social Networks: Case of the COVID-19 Pandemic. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 158806–158825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denecke, K.; Vaaheesan, S.; Arulnathan, A. A Mental Health Chatbot for Regulating Emotions (SERMO)—Concept and Usability Test. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. 2021, 9, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Oh, K.-J.; Choi, H.-J. The chatbot feels you—A counseling service using emotional response generation. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 13–16 February 2017; pp. 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.; Bravo-Marquez, F.; Salameh, M.; Kiritchenko, S. Semeval-2018 task 1: Affect in tweets. In Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–6 June 2018; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Elfaik, H.; Nfaoui, E.H. Social Arabic Emotion Analysis: A Comparative Study of Multiclass Classification Techniques. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference On Intelligent Computing in Data Sciences (ICDS), Fez, Morocco, 20–22 October 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alswaidan, N.; Menai, M.E.B. Hybrid feature model for emotion recognition in Arabic text. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 37843–37854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfaik, H.; Nfaoui, E.H. Combining Context-Aware Embeddings and an Attentional Deep Learning Model for Arabic Affect Analysis on Twitter. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 111214–111230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EKhalil, A.H.H.; El Houby, E.M.F.E.F.; Mohamed, H.K. Deep learning for emotion analysis in Arabic tweets. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansy, A.; Rady, S.; Gharib, T. An Ensemble Deep Learning Approach for Emotion Detection in Arabic Tweets. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASamy, E.; El-Beltagy, S.R.; Hassanien, E. A context integrated model for multi-label emotion detection. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 142, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Elfaik, H.; Nfaoui, E.H. Leveraging feature-level fusion representations and attentional bidirectional RNN-CNN deep models for Arabic affect analysis on Twitter. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 462–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khondaker, M.T.I.; Waheed, A.; Nagoudi, E.M.B.; Abdul-Mageed, M. GPTAraEval: A comprehensive evaluation of ChatGPT on Arabic NLP. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.14976. [Google Scholar]

- Alyafeai, Z.; Alshaibani, M.S.; AlKhamissi, B.; Luqman, H.; Alareqi, E.; Fadel, A. Taqyim: Evaluating arabic nlp tasks using chatgpt models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.16322. [Google Scholar]

- Sallam, M.; Mousa, D. Evaluating ChatGPT performance in Arabic dialects: A comparative study showing defects in responding to Jordanian and Tunisian general health prompts. Mesopotamian J. Artif. Intell. Healthc. 2024, 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI API, “Fine-Tuning,” 2023. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/fine-tuning (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Li, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Hou, W.; Lian, J.; Luo, F.; Yang, Q.; Xie, X. Large Language Models Understand and Can be Enhanced by Emotional Stimuli. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.11760. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI, “OpenAI Models,” 2023. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/overview (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Tao, W.; Liotta, A.; Yang, D.; Li, X.; Gao, S.; Sun, Y.; Ge, W.; Zhang, W.; et al. A systematic review on affective computing: Emotion models, databases, and recent advances. Inf. Fusion 2022, 83–84, 19–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A. Basic Dimensions for a General Psychological Theory: Implications for Personality, Social, Environmental, and Developmental Studies; Oelgeschlager, Gunn & Hain: Cambridge, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. Basic emotions. Handb. Cogn. Emot. 1999, 98, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Plutchik, R. Emotions and Life: Perspectives from Psychology, Biology, and Evolution; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cambria, E.; Livingstone, A.; Hussain, A. The hourglass of emotions. In Cognitive Behavioural Systems: COST 2102 International Training School, Dresden, Germany, 21–26 February 2011, Revised Selected Papers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 144–157. [Google Scholar]

- Susanto, Y.; Livingstone, A.G.; Ng, B.C.; Cambria, E. The Hourglass Model Revisited. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2020, 35, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.T.; de Aguiar, E.; De Souza, A.F.; Oliveira-Santos, T. Facial expression recognition with Convolutional Neural Networks: Coping with few data and the training sample order. Pattern Recognit. 2017, 61, 610–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Baird, A.; Han, J.; Zhang, Z.; Schuller, B. Generating and Protecting Against Adversarial Attacks for Deep Speech-Based Emotion Recognition Models. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 7184–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, F.A.; Wenyu, C.; Nunoo-Mensah, H. Text-based emotion detection: Advances, challenges, and opportunities. Eng. Rep. 2020, 2, e12189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Gohary, A.F.; Sultan, T.I.; Hana, M.A.; El Dosoky, M.M. A computational approach for analyzing and detecting emotions in Arabic text. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2013, 3, 100–107. [Google Scholar]

- AAl-Aziz, M.A.; Gheith, M.; Eldin, A.S. Lexicon based and multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) approach for detecting emotions from Arabic microblog text. In Proceedings of the 2015 First International Conference on Arabic Computational Linguistics (ACLing), Cairo, Egypt, 17–20 April 2015; pp. 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Al-A’abed, M.; Al-Ayyoub, M. A lexicon-based approach for emotion analysis of arabic social media content. In Proceedings of the International Computer Sciences and Informatics Conference (ICSIC), Amman, Jordan, 12–13 January 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, S.M.; Kiritchenko, S.; Zhu, X. NRC-Canada: Building the state-of-the-art in sentiment analysis of tweets. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1308.6242. [Google Scholar]

- Rabie, O.; Sturm, C. Feel the heat: Emotion detection in Arabic social media content. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Mining, Internet Computing, and Big Data (BigData2014), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–19 November 2014; pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hussien, W.A.; Tashtoush, Y.M.; Al-Ayyoub, M.; Al-Kabi, M.N. Are emoticons good enough to train emotion classifiers of arabic tweets? In Proceedings of the 2016 7th International Conference on Computer Science and Information Technology (CSIT), Amman, Jordan, 12–13 January 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, A.M.; AbdelRahman, S.; Bahgat, R.; Fahmy, A. Time emotional analysis of arabic tweets at multiple levels. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7, 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulllah, M.; AlMasawa, M.O.; Makki, I.S.; Alsolmi, M.J.; Mahrous, S.S. Emotions classification for Arabic tweets. J. Fundam. Appl. Sci. 2018, 10, 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khatib, A.; El-Beltagy, S.R. Emotional tone detection in arabic tweets. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing, Budapest, Hungary, 17–23 April 2017; pp. 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Badaro, G.; El Jundi, O.; Khaddaj, A.; Maarouf, A.; Kain, R.; Hajj, H.; El-Hajj, W. EMA at semeval-2018 task 1: Emotion mining for arabic. In Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–6 June 2018; pp. 236–244. [Google Scholar]

- Mulki, H.; Ali, C.B.; Haddad, H.; Babaoğlu, I. Tw-star at semeval-2018 task 1: Preprocessing impact on multi-label emotion classification. In Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–6 June 2018; pp. 167–171. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Shaikh, S. Teamuncc at semeval-2018 task 1: Emotion detection in english and arabic tweets using deep learning. In Proceedings of the 12th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation, New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–6 June 2018; pp. 350–357. [Google Scholar]

- Jabreel, M.; Moreno, A. EiTAKA at SemEval-2018 Task 1: An ensemble of n-channels ConvNet and XGboost regressors for emotion analysis of tweets. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.09233. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, M.; Hadzikadicy, M.; Shaikhz, S. Sedat: Sentiment and emotion detection in arabic text using cnn-lstm deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 17th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Orlando, FL, USA, 17–20 December 2018; pp. 835–840. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner, B.; Rocktäschel, T.; Bošnjak, M.; Riedel, S. emoji2vec: Learning Emoji Representations from Their Description. Available online: https://twitter.com/Kyle_MacLachlan/ (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Soliman, A.B.; Eissa, K.; El-Beltagy, S.R. Aravec: A set of arabic word embedding models for use in arabic nlp. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 117, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanowski, P.; Grave, E.; Joulin, A.; Mikolov, T. Enriching Word Vectors with Subword Information. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2017, 5, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D. Glove: Global vectors for word representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1532–1543. [Google Scholar]

- AlZoubi, O.; Tawalbeh, S.K.S.K.S.K.; AL-Smadi, M. Affect detection from arabic tweets using ensemble and deep learning techniques. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 2529–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baali, M.; Ghneim, N. Emotion analysis of Arabic tweets using deep learning approach. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, M. Talking about large language models. Commun. ACM 2024, 67, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Q.; Li, L.; Dai, D.; Zheng, C.; Wu, Z.; Chang, B.; Sun, X.; Xu, J.; Li, L.; Sui, Z. A survey on in-context learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2301.00234. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Chang, K.C.-C. Towards reasoning in large language models: A survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.10403. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L.; Constant, N.; Roberts, A.; Kale, M.; Al-Rfou’, R.; Siddhant, A.; Barua, A.; Raffel, C. mT5: A massively multilingual pre-trained text-to-text transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11934. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI API, “Chat Completions API,” 2023. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/api-reference/chat (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Farha, I.A.; Magdy, W. A comparative study of effective approaches for Arabic sentiment analysis. Inf. Process. Manag. 2021, 58, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.; Mahmoud, T.M.; Abd-El-Hafeez, T.; Mahfouz, A. Multi-label arabic text classification in online social networks. Inf. Syst. 2021, 100, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI, “Models Multilingual Capabilities.” 2023. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/multilingual-capabilities (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Lai, V.; Ngo, N.; Ben Veyseh, A.P.; Man, H.; Dernoncourt, F.; Bui, T.; Nguyen, T. Chatgpt beyond english: Towards a comprehensive evaluation of large language models in multilingual learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.05613. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI, “OpenAI Prompt Engineering Guide.” 2023. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/prompt-engineering (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Honovich, O.; Shaham, U.; Bowman, S.R.; Levy, O. Instruction Induction: From Few Examples to Natural Language Task Descriptions. Proc. Annu. Meet. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2022, 1, 1935–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madjarov, G.; Kocev, D.; Gjorgjevikj, D.; Džeroski, S. An extensive experimental comparison of methods for multi-label learning. Pattern Recognit. 2012, 45, 3084–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.-L.; Zhou, Z.-H. A review on multi-label learning algorithms. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2013, 26, 1819–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.M.; Chen, J.-H. A multi-label classification based approach for sentiment classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Japkowicz, N.; Szpakowicz, S. Beyond accuracy, F-score and ROC: A family of discriminant measures for performance evaluation. In Australasian Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume WS-06-06, pp. 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Y.; Cahyawijaya, S.; Lee, N.; Dai, W.; Su, D.; Wilie, B.; Lovenia, H.; Ji, Z.; Yu, T.; Chung, W.; et al. A Multitask, Multilingual, Multimodal Evaluation of ChatGPT on Reasoning, Hallucination, and Interactivity. In Proceedings of the 13th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing and the 3rd Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguisticss, Nusa Dua, Bali, 1–4 November 2023; pp. 675–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Tang, T.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, X.; Song, T.; Xia, Y.; Wei, F. Not All Languages Are Created Equal in LLMs: Improving Multilingual Capability by Cross-Lingual-Thought Prompting. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 12365–12394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubaa, A.; Ammar, A.; Ghouti, L.; Najar, O.; Sibaee, S. ArabianGPT: Native Arabic GPT-based Large Language Model. February 2024. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.15313v2 (accessed on 29 April 2024).

| Subtask a | Model/Year | Results (%) | Approach | Data Source | Features | Emotion Model | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML | DL | |||||||

| E-c | H. Elfaik & Nfaoui, 2023 [20] | Accuracy: 60 Micro F1: 52 Macro-F1: 35 | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 | Feature-level fusion representation | Plutchik’s model |

|

| Mansy et al., 2022 [18] | Accuracy: 54 Micro F1: 52.7 Macro-F1: 70.1 | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 | AraVec word embeddings | Plutchik’s model + “love”, “optimism”, and “pessimism” |

| |

| H. Elfaik & Nfaoui, 2021 [16] | Accuracy: 53.82 | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 | AraBERT pre-trained embedding | Plutchik’s model |

| |

| Khalil et al., 2021 [17] | Accuracy: 49.8 | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 | AraVec word embeddings |

| ||

| Alswaidan & Menai, 2020 [15] | Accuracy: 51.20 | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 IAEDS AETD | Stylistic, lexical, syntactic, and semantic features. | Plutchik’s model + “love”, “optimism”, and “pessimism” |

| |

| Samy et al., 2018 [19] | Accuracy: 53.2 Micro F1: 49.5 Macro F1: 64.8 | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 | Plutchik’s model + “love”, “optimism”, and “pessimism” |

| ||

| Abdullah & Shaikh, 2018 [49] | Accuracy: 44.6 | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 | Word and Document embedding, Psychological Linguistic features | Plutchik’s model |

| |

| Badaro et al., 2018 [47] | Accuracy: 48.9 Micro F1: 61.8 Macro F1: 46.1 | ✓ | ✗ | SemEval-2018 | N-grams, lexicons, Word embedding, Fast-Text | Plutchik’s model |

| |

| Mulki et al., 2018 [48] | Accuracy: 46.5 | ✓ | ✗ | SemEval-2018 | TF-IDF | Plutchik’s model |

| |

| Abd Al-Aziz et al., 2015 [39] | 2-D graphical representation | ✗ | ✗ | Happiness, sadness, fear, anger, and disgust |

| |||

| M-c | Abdulllah et al., 2018 [45] | Accuracy, SVM: 80.6, NB: 95 | ✓ | ✗ | TF-IDF |

| ||

| Al-Khatib & El-Beltagy, 2017 [46] | Accuracy: 68.12 | ✓ | ✗ | AETD | N-grams, feature vector, BOW | Sadness, anger, joy, surprise, love, sympathy, fear, no emotion” |

| |

| Hussien et al., 2016 [43] | F1-measure, SVM: 72.26 MNB: 75.34 | ✓ | ✗ | BOW, TF-IDF | Anger, disgust, joy and sadness. |

| ||

| Sayed et al., 2016 [44] | F1-measure, CRF: 72.60 AdaBoost: 53.45 | ✓ | ✗ | Word features, Tweet features, Structure features | Sadness, happiness, anger, surprise and sarcasm. |

| ||

| Rabie & Sturm, 2014 [42] | Accuracy: 64.3 | ✓ | ✗ | Ekman’s model |

| |||

| El Gohary et al., 2013 [38] | Accuracy: 54 Micro F1: 52.7 Macro-F1: 70.1 | ✗ | ✗ | Arabic children’s stories | Word, sentence, and document level | Ekman + Neutral and Mixed category |

| |

| EI-oc | Baali & Ghneim, 2019 [57] | Validation accuracy: 99.82 | ✓ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 |

| ||

| Abdullah et al., 2018 [51] | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 | Word and Document embedding |

| |||

| V-reg | Jabreel & Moreno, 2018 [50] | Pearson, ENG: 82, ARA: 82 | ✓ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 | Lexicon Features, Embedding Features | Anger, fear, joy, sadness |

|

| EI-reg | AlZoubi et al., 2022 [56] | Pearson, 69.2 | ✗ | ✓ | SemEval-2018 |

| ||

| No. | Emotion Label | Number of Tweets | Distribution (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train | Dev | Test | Train | Dev | Test | ||

| 0 | Anger | 899 | 215 | 609 | 39.46 | 36.75 | 40.12 |

| 1 | Anticipation | 209 | 57 | 158 | 09.17 | 09.74 | 10.41 |

| 2 | Disgust | 433 | 106 | 316 | 19.00 | 18.12 | 20.82 |

| 3 | Fear | 391 | 94 | 295 | 17.16 | 16.07 | 19.43 |

| 4 | Joy | 605 | 179 | 393 | 26.56 | 30.60 | 25.89 |

| 5 | Love | 562 | 175 | 367 | 24.67 | 29.91 | 24.18 |

| 6 | Optimism | 561 | 169 | 344 | 24.62 | 28.89 | 22.66 |

| 7 | Pessimism | 499 | 125 | 377 | 21.90 | 21.37 | 24.83 |

| 8 | Sadness | 842 | 217 | 579 | 36.96 | 37.09 | 38.14 |

| 9 | Surprise | 47 | 13 | 38 | 02.06 | 02.22 | 02.50 |

| 10 | Trust | 120 | 36 | 77 | 05.27 | 06.15 | 05.07 |

| Setting | Jaccard Accuracy | Micro-Averaged F1-Score | Macro-Averaged F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model_1: Fine-tuned GPT-3.5-turbo model (n_epochs = 3) | 62.03% | 73.00% | 62.00% |

| Model_2: Fine-tuned GPT-3.5-turbo model (n_epochs = 5) | 61.91% | 72.00% | 61.00% |

| SOTA: Elfaik and Nfaoui, 2023 [20] | 60.00% | 52.00% | 35.00% |

| GPT-4 (EmotionPrompt within Few-Shot) | 54.22% | 65.00% | 58.00% |

| Mansy et al., 2022 [18] | 54.00% | 52.7% | 70.10% |

| Elfaik and Nfaoui, 2021 [16] | 53.82% | - | - |

| GPT-4 (Zero-Shot) | 53.07% | 65.00% | 55.00% |

| GPT-4 (EmotionPrompt within Zero-Shot) | 52.92% | 64.00% | 54.00% |

| Alswaidan and Menai, 2020 [15] | 51.20% | 63.10% | 50.20% |

| Khalil et al., 2021 [17] | 49.80% | 61.50% | 44.00% |

| EMA Team [47] | 48.90% | 61.80% | 46.10% |

| GPT-3.5-turbo (Few-Shot) | 48.56% | 59.00% | 51.00% |

| GPT-3.5-turbo (Zero-Shot) | 48.15% | 58.00% | 46.00% |

| GPT-3.5-turbo (One-Shot) | 45.49% | 56.00% | 49.00% |

| Emotional Label | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model_1 | Model_2 | Model_3 | Model_1 | Model_2 | Model_3 | Model_1 | Model_2 | Model_3 | |

| anger | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.70 |

| anticipation | 0.49 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.03 |

| disgust | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.45 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.35 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.39 |

| fear | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.38 | 0.73 | 0.76 | 0.11 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.17 |

| joy | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.54 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.65 |

| love | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.78 | 0.46 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.57 |

| optimism | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.52 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.62 |

| pessimism | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.33 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.16 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.22 |

| sadness | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.45 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.55 |

| surprise | 0.44 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| trust | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.00 |

| Micro-Avg | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.66 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.42 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.52 |

| Macro-Avg | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.35 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nfaoui, E.H.; Elfaik, H. Evaluating Arabic Emotion Recognition Task Using ChatGPT Models: A Comparative Analysis between Emotional Stimuli Prompt, Fine-Tuning, and In-Context Learning. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1118-1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19020058

Nfaoui EH, Elfaik H. Evaluating Arabic Emotion Recognition Task Using ChatGPT Models: A Comparative Analysis between Emotional Stimuli Prompt, Fine-Tuning, and In-Context Learning. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2024; 19(2):1118-1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19020058

Chicago/Turabian StyleNfaoui, El Habib, and Hanane Elfaik. 2024. "Evaluating Arabic Emotion Recognition Task Using ChatGPT Models: A Comparative Analysis between Emotional Stimuli Prompt, Fine-Tuning, and In-Context Learning" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 19, no. 2: 1118-1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19020058

APA StyleNfaoui, E. H., & Elfaik, H. (2024). Evaluating Arabic Emotion Recognition Task Using ChatGPT Models: A Comparative Analysis between Emotional Stimuli Prompt, Fine-Tuning, and In-Context Learning. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(2), 1118-1141. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer19020058