Abstract

This research aims to conceptualize, develop, and validate a specific instrument for measuring the engagement of followers towards influencers on social media, and more specifically, in this first research, on Instagram. We surveyed (in-depth interviews, and questionnaires) 32 marketing experts and 1170 Instagram followers. Based on the applications of factor analysis and structural equation modelling, we determined 21 valid items. The scale assesses the cognitive, affective, and behavioral characteristics of follower’s engagement across five dimensions. The results provide insight into the interactive, personal, and social aspects of this type of virtual engagement. It is the first scale to measure this engagement in a multidimensional framework, which advances future research. Additionally, it will help managers identify the strongest dimensions of their influencers’ engagement and thus be able to adjust marketing communication strategies to foster multidimensional follower engagement and subsequent partnerships.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, researchers and marketers have examined the nature and dynamics of the relationship between brands and consumers, which are construed as acting as partners [1]. Research has found that the interactive capabilities of social media (SM) can provide a conceptual parallel to the conversational nature underlying the concept of engagement [2,3]. For example, SM users’ interactions with specific brands are concrete manifestations of engagement marked by varying degrees of affective and/or cognitive and/or behavioral investment [4]. By providing access to online content and facilitating communication, SMs greatly bring consumers closer to organizations. As a result, online platforms have led companies to adapt their influence strategies to build strong relationships with users and thus increase their engagement rate [5].

The scientific literature on consumer engagement affirms that interactivity with the brand is a prerequisite for engagement [6,7]. However, consumers are sensitive to the perception of two-way communication and the reactions to their actions. They are looking for authentic content that is closer to their reality [8,9]. Thus, an increasing share of consumer engagement interactions are with human brands (HB) (e.g., singer, athlete) in the digital environment, including SM influencers [10,11]. Indeed, some users of Instagram (IG), TikTok, and other sister platforms have become active content creators. Often, they share stories from their daily lives [12,13], which makes them more influential than traditional celebrities as they are perceived as more credible and accessible [14]. This new type of HB—influencer—acts actively and in collaboration with their followers and approved brands [15,16], for example by commenting on the products they have tested and offering a promotional code to their followers [17,18].

Given that SM are dialogue based [19], we believe that strategic communications management is necessary in order to support a sustainable engagement process between followers and influencers [20]. Moreover, Levesque et al. (2023) [21] demonstrated how useful the influencer-follower relationship can be for their common well-being. Therefore, a holistic reflection bringing together both social and interactive components [22] inherent in the engagement relationship under study, would improve the predictive and explanatory power of consumer behavior models [23,24,25] and would allow a better understanding of the mental schemas that shape the daily lives of SM users regarding influencers.

To the best of our knowledge, the literature on influencer and on conceptualizing consumer engagement with this new HB is very limited. Further, tools that measure consumer engagement with an inanimate brand sometimes focus on a single dimension of engagement (e.g., behavioral, see [26]) or on measuring brand usage [27], visitor engagement [28] which is hardly applicable to a HB [29]. Many researchers fail to consider that the expression of engagement dimensions varies considerably across objects and contexts [30]. In addition, the engagement rate is different depending on the areas of interest of the influencers [31]. Thus, due to the distinctiveness of HB (e.g., living being), current measurement instruments are not applicable to the study context. This is an important point given that high engagement can lead followers to voluntarily act as an influencer’s ambassador in their circle [32]. The objective of this research is therefore to conceptualize, develop and validate a measurement instrument specifically adapted to the context influencer engagement on social media (IESM), and more particularly on Instagram. Therefore, we will answer the following research questions:

- How is the concept of engagement with the influencer on SM articulated?

- What are the existing measurement tools relating to this type of engagement?

- How effective are they in the context studied?

This study contributes to the scientific literature by providing a theoretical basis for follower engagement, by specifying the interactive, personal, and social aspects that constitute this relationship. The contextually unique measurement scale highlights mental and behavioral patterns that may reinforce IESM in a multidimensional manner. The tool also allows influencer to determine the strongest dimensions of engagement and to adjust their marketing communication strategies to heighten follower engagement. Thus, the study provides implications for academics, managers (e.g., an influencer agent) and influencers.

This article is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the literature on consumer engagement. Section 3 explains the methodology, which consists of five consecutive qualitative (in-depth interviews) and quantitative (questionnaires) steps. Section 4 presents the analysis and the results, and Section 5 concludes the paper with a discussion that includes avenues for future research and academic and managerial implications.

2. Review of the Literature

The conceptual foundations of consumer engagement build on relationship marketing theory [29]. For a company, a relationship orientation typically creates a competitive advantage, which in turn exerts a positive impact on its performance [2]. However, in addition to myriad types of engagement described in the marketing literature (e.g., brand engagement in self-concept [33], customer brand engagement [34] or consumer brand engagement [35]), definitions of engagement also abound. Hollebeek (2011) [4] construes engagement as the consumer’s level of motivation relative to the brand and their context-dependent state of mind, characterized by specific levels of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral activities. Brodie et al. (2011) [29] define engagement as a psychological state induced by consumer’s interactivity and co-creative experiences with the object. Although some definitions have aspects in common, scientific support on the nature of the concept of engagement in marketing is scant [36,37]. There is also a lack of consensus on the dimensionality of engagement [4,33]. Views diverge over the combination and number of dimensions and sub-dimensions involved in the process [38].

2.1. Dimensionality and Measurement of Engagement

Some researchers view engagement in a one-dimensional way [39,40,41] (e.g., clicking on online content). Other scholars argue that brand engagement should be viewed instead as a manifestation of engagement rather than an operational definition of this concept [42]. However, studies show that to offer an exceptional engagement experience, multiple dimensions must be stimulated simultaneously [43,44]. The marketing literature demonstrates that engagement is commonly measured along three dimensions, cognitive, affective/emotional, and behavioral/activation (e.g., Lourenço et al., 2022 [45]; Hollebeek et al., 2014 [30]).

2.2. Cognitive

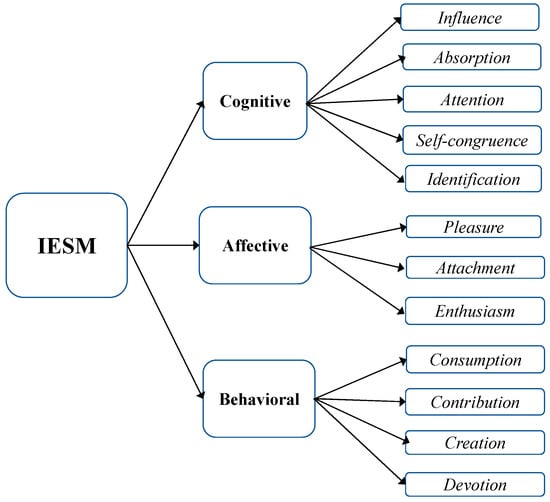

The cognitive dimension consists of information processing, i.e., the perception of a brand’s usefulness and relevance. It is measured by various sub-dimensions such as influence (experience), which refers to a brand’s impact (positive or negative) in a consumer’s life [46,47]. Absorption is another sub-dimension mobilized in studies of cognitive engagement [22,48]. According to the flow theory [49], the disposition of deep absorption in an intrinsically pleasurable activity leads to strong engagement. Another dimension related to the cognitive aspect is attention [3,4]. This is the degree of concentration relative to a brand. The higher it is, the more the consumer is engaged with the subject. Then, self-congruity [50] is used to measure the identity aspect of cognitive engagement. The consumer integrates the identity signal of a brand into his self-concept [51] which allows him to define himself by projecting a certain image to those around him [33]. In addition, self-congruence [50] is used to measure the identity aspect of cognitive engagement. The last sub-dimension is identification, which is when the consumer’s self-image overlaps with that of the brand [52,53], whether real, social, ideal, or social-ideal [50].

2.3. Affective

The affective dimension is based on emotional congruence with the brand characterized by enthusiasm [48,54] and pleasure [55]. The affective aspect also includes attachment. Derived from experiences, emotions, and expectations associated with a brand [56], attachment motivates individuals to engage in and adopt specific behaviors [57]. In addition, studies in psychology have found a positive correlation between engagement and personal well-being (e.g., [58,59]). The more engaged the individual is, the higher their life satisfaction [38].

2.4. Behavioral

The behavioral dimension represents the consumer’s activation towards the brand [30]. Various actions can be considered manifestations of engagement, for example word-of-mouth [60], compulsive buying [61], as well as participation and interaction/co-creation [54]. Indeed, past studies have underscored the importance of interactivity in the consumer-brand dyad, as it enables voluntary effort to maintain a level of interaction that elicits continued engagement (e.g., [29,36]). Obviously, through SM, the consumer is able to interact directly with the brand [62], faster than in an offline context [63,64]. By the same token, the conceptualization and operationalization of behavioral engagement underwent a major transformation during the 2000s.

SM have transformed the nature and practice of online communication into an extensive two-way dialogue between users [65] and brands. Digital technologies facilitate users’ social participation [66] and progressively build intimacy [67], thus engendering novel behaviors that establish new social norms [68,69]. However, consensus about what constitutes behavioral engagement on SM is lacking [70]. Some authors measure engagement by the number of brand followers [71], while others link it to specific actions (e.g., the number of “likes” of a post) [72]. On the other hand, obtaining “likes” is a low engagement action and brands want more engaged and active exchanges with their followers (e.g., a comment, a share) [73]. It is therefore essential to differentiate the levels of behavioral engagement in the digital context.

The Consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRA) behavioral construct [72,74] provides a unifying framework for analyzing consumers’ activities related to a brand’s content on SM [26]. COBRA activities are classified under three dimensions corresponding to a path of gradual involvement [72]. The first level is consuming, which entails followers’ passive participation in online brand communities [75]. One such example is reading. The second level is contributing; it includes interaction with brand-related content [76], and is exemplified by sharing. The third level is creating, which includes publishing original brand-related content [77], e.g., create a story (The stories are an option of the application on IG which allows to realize ephemeral visual content (for a duration of 24 h) by identifying an influencer. It should be noted that behavioral engagement can even go as far as consumer devotion, i.e., the manifestation of his devotion to a brand with his network. Voluntary, this ambassador can influence consumers to the benefit or disadvantage of the adored brand [32].

The literature on engagement confirms both the complexity of the concept and its importance to brands. The dimensions identified underline the multifaceted nature of the subject and the variety of fields of research interest [78]. Table 1 presents the main consumer engagement measurement scales used in marketing. However, HB is not managed in the same way as an inanimate brand [79]. This confirms that the concept is not surfing on a “trendy” keyword and that having measurement tools capturing its specificities is necessary. In the next section, we demonstrate the uniqueness of HB.

Table 1.

Main consumer engagement measurement scales used in marketing.

2.5. Characteristics of the Human Brand

The HB is differentiated from traditional brands owing to its human aspect. The human brand is imbued with physical and social realities, prejudices, and limitations. Although the HB poses risks related to management of its image, it also offers advantages in terms of the potential to improve the returns on the brand [96]. In addition, the HB has a wider range of attributes than does an inanimate brand and can adapt to the circumstances surrounding it. The HB also has a significantly greater capacity for reciprocity with the consumer than a traditional brand [97]. The bond between an HB and a consumer is similar to interpersonal relationships, especially in SM [63,64]. Indeed, many followers develop a parasocial relationship with an influencer—an imaginary relationship of friendship or love towards a media person [98,99]. A parasocial relationship enhances the perceived credibility of the influencer and positively affects brand trust and follower behavior [100].

However, while HB is extremely powerful, it is also very risky. Indeed, he is not immune to the risks of adverse events such as illness or misconduct [96]. For example, in 2020, Maripier Morin (Quebec host, television columnist, businesswoman and actress) saw her empire crumble when she admitted to accusations of sexual harassment, physical assault and racist remarks. Her business partners could not appear in the scandalous image of the actress and host. She was dumped by the brands she represented. In addition, Bell Media and Videotron have removed its television programs on all their platforms [101]. The main dangers that the human body imposes on HB are mortality, hubris, unpredictability, and social entrenchment. These characteristics lend it a particularly high level of authenticity and resonance, which enhances its value from consumers’ standpoint [102]. This supports the importance of considering the living nature of HB when examining the engagement relationship [97].

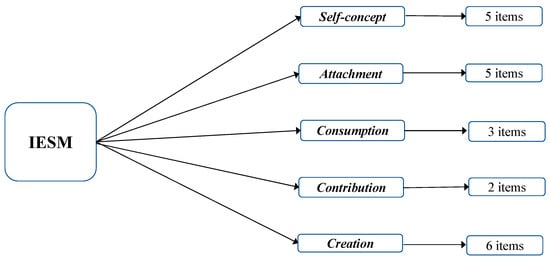

As mentioned earlier, engagement in marketing has primarily been measured in the context of the consumer-brand relationship [103]. We also observe that the items used apply to the use of traditional brands and/or in specific and often offline contexts (e.g., engagement to art, [46]). Moreover, depending on the interests of the influencers, the engagement differs [31]. This calls into question the relevance of current measuring instruments for influencer on SM. Admittedly, scales applying to the context of SMs have been listed, but they are intended to measure engagement to platforms or websites [42,82], which is difficult to transfer to HB [30,104]. Additionally, the rapid consumption pattern on SMs [105] and two-way exchanges with SM suggest unique engagement process and behaviors that existing measurement tools do not capture. We therefore conclude that due to the uniqueness of HB and the context under study, the available measurement tools are not applicable. We propose the development of the Influencer Engagement Scale on Social Media (IESM). Table 2 summarizes the dimensions and sub-dimensions of engagement with an influencer and Figure 1 presents the theoretical model.

Table 2.

Dimensions and Sub-Dimensions of Engagement with an Influencer.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of the IESM scale.

3. Methodology

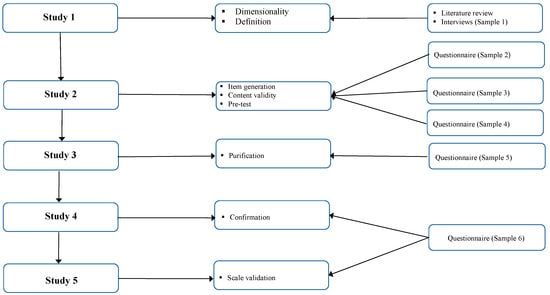

Nowadays, IG is one of the most effective advertisings channels: 90% of accounts follow at least one company on this platform [112]. IG generated revenues of over US$51.4 billion in 2022 [113]. With more than 2.35 billion monthly users, 93% of the brands use IG for influencer marketing [114]. It is one of the best performing platforms in terms of engagement. Its average rate is 0.47% as opposed to 0.06% for FB and 0.03% for Twitter [114]. In addition, IG is a strategic self-promotion tool for influencers [115]—90% of them are active on this platform [116]. In doing so, because of the immediacy, the creativity it offers, the community it helps to develop and the engagement it generates [117], IG is the social platform of choice for influencers. This justifies the choice of IG as the social platform for this study. Figure 2 illustrates the process of developing the measurement scale following the paradigm of [118] and Table 3 presents the samples used. The researchers did the recruitment via their personal social media account (IG, FB, LinkedIn), and the data collection took place from June to September 2021. As the COVID-19 pandemic was very present at that time, the in-depth interviews took place via Zoom and the self-administered questionnaires on the Google Forms platform. It is therefore a convenient sample, a form of non-probability sampling. Most of the respondents were from the province of Quebec, Canada. The rigor of this method will make it possible to answer the three research questions.

Figure 2.

Scale development and validation process.

Table 3.

Summary of steps followed and samples used.

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Step 1: Dimensionality and Definition

Step 1 aims to deepen our understanding by examining the conceptualization and dimensions of IESM. The analysis is based on the literature review and the first qualitative phase. We conducted in-depth interviews (n = 13) with 5 followers (A) and 8 experts in marketing (E) (8F, 5M). Respondents described their experience with an influencer and provided a definition of IESM. We conducted open, axial, and selective coding [119]. Based on our questionnaire, we analyzed the verbatim inductively in Excel, in order to identify central meanings and significant terms. Then, we formed groups by exploring the links between the different categories retained. Next, we reduced the number of dimensions of engagement by eliminating redundant or similar dimensions [120].

Consistent with previous studies on consumer engagement (e.g., [29]), IESM is a multidimensional construct. However, each of the respondents added depth to the meaning of the dimensions. E11 (F, age 28): “So, that’s why I’m telling you [there’s] some brand love around the influencer.” A5 (M, age 31): “You’re going to follow their values and their way of thinking. Because that’s what makes you follow them [influencers] and enjoy the content they give you.”

Definitions

The influencer is perceived as a model with whom followers identify, whom they wish to resemble and who is able to influence their actions and thoughts. E13 (F, 29): “You end up knowing the lives of these people, you end up wanting to be like them.” According to the respondents, the two major reasons why a follower follows an influencer are because they are inspiring or to keep up with trends. Further, respondents mentioned that the level of engagement varies depending on the category of influencer (number of followers). The literature shows that influencers with smaller communities have higher engagement rates [121]. Respondents noted that the influencer may promote a brand or simply share an experience.

Regarding engagement, the interviews indicated that followers can be passively (e.g., apprehending information) or actively engaged (e.g., making a purchase following a recommendation). The literature on online engagement in particular divides the nature of information consumption into two categories (active and passive) [73,122]. Additionally, followers engage with an influencer out of admiration, but also to satisfy a sense of belonging. What the SM allow with their numerous communities of followers. To this end, perceived social support encourages community spirit, sharing, communication and belonging to social groups with similar characteristics [123]. Finally, followers were aware that this type of engagement has a variety of consequences, including loss of time, distortion of reality, overconsumption, feeling less alone and stronger, and the feeling of having a daily friend. Thus, using the results of this first step and taking into account the existing literature, we are led to specify the definition of an influencer in the context of our study as being:

Influencers are very active individuals on social media, where they post content about themselves, their expertise, their areas of interest and/or their daily life with their community. These people are perceived as models in which their followers recognize themselves or aspire to imitate. Influencers use their personal brand to share information and potentially guide the attitude and behavior of their community. This is based on the expertise of the influencer and the trust of his followers. Influencer activity may have a business purpose through brand endorsement, or it may simply communicate relevant experiences to their followers. Influencers can have less than 10,000 followers or more than a million.

In addition, we refine the definition of engagement (IESM): “A follower’s willingness to think about or interact with an influencer or the content the influencer posts on SM, such as sharing a post.” Table A1 summarizes the quotes selected to inform the definition. The initial 103 items of the scale were developed based on the literature combined with these interviews.

4.2. Step 2: Item Generation, Content Validation and Pre-Testing

Step 2 is designed to generate additional items and ensure content validity [124]. We solicited marketing professors and doctoral students (n = 14) by email including a hyperlink directing them to a questionnaire on the Google Forms platform. After reading the definitions, the judges evaluated the correspondence of the proposed items (yes or no). We retained the items that at least half of the judges found to be relevant. Analysis of the questionnaires showed that some sub-dimensions overlapped due to their similar meaning, e.g., Self-Congruence and Identification.

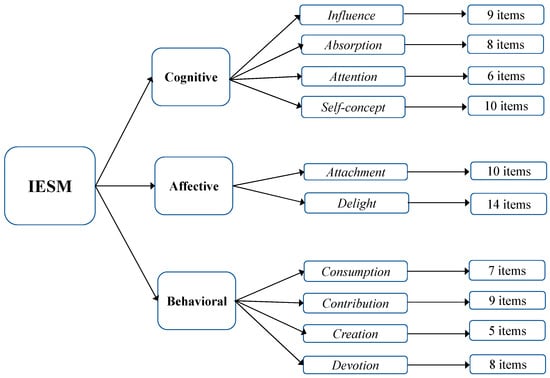

Their association is logical, because if part of the follower is defined by his interactions with his influencer, he perceives a form of self-congruence with his self-concept [50]. The two sub-dimensions were grouped under Self-concept: “Self-definition between the image projected by the influencer and one of the facets of the follower’s self-concept” (inspired by [50]). In addition, both Enthusiasm and Pleasure referred to followers’ delight for their influencer: “The intrinsic level of happiness experienced by a follower for an influencer: They feel strong joy, admiration, and enthusiasm” (inspired by [4,110]). We merged these items under Delight. We also solicited the expertise of participants to provide additional items. Finally, 22 items were deleted and 14 added. The exercise reduced the number of items to 95. This confirms that both experts and followers have a similar perception. We then validated the new items by consulting 10 other professors and doctoral students in administration (sample #3). In the same way as in the previous collection, we asked them to evaluate the items. Following the analysis of the questionnaires, we retained 86 items, three dimensions and 10 sub-dimensions (Figure 3). Finally, we pre-tested the questionnaire with six followers (sample #4). This pilot test allowed us to move on to step 3.

Figure 3.

IESM Model (Step 2).

4.3. Step 3: Purification of the Scale

Step 3 was designed to evaluate the structure and psychometric properties of the scale [118]. Participants were recruited through postings on IG, FB, and LinkedIn. The posts stated the following eligibility criteria: (1) Be 18 years of age or older; (2) Have accessed IG in the past 30 days; and (3) Be following an influencer. A hyperlink to the survey was embedded in the posts. In order to ensure broad participation, we contacted a Montreal-based (J’influence, https://jinfluence.biz, accessed on 3 July 2023) influencer agency and asked them to invite one of their clients to share our hyperlink. Camille Dufresne, a well-known influencer in Quebec (88.6 k IG followers) (@camilledufresne_, 88.2 followers on IG as of 3 July 2023), made an IG story with a link leading to the questionnaire. First, participants read the definitions and indicated the name of the influencer with whom they felt most engaged. Then, the 86 items were randomly presented to them. They were all positively formatted according to a 5-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree). The survey concluded with socio-demographic questions. We obtained 377 questionnaires and after eliminating those that did not meet the eligibility requirements (many were under 18) and incomplete ones, the final size of sample #5 is 230 respondents (61% of initiated questionnaires).

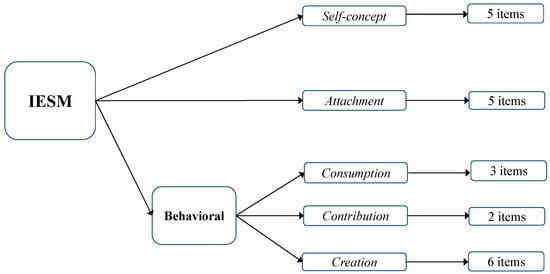

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed using SPSS 27 software. The fit of the indices was significant. To conserve sample size, we transformed missing data (186 out of 19,509) by the mean item score [125,126]. The Kaiser-Meyer-Oklin (KMO) statistic was 0.926, which exceeds the recommended level of 0.70 [127]. Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicated the existence of significant correlations between the variables: chi-square of 10,051.62 with 210 degrees of freedom (dl) (p < 0.001). Subsequently, a series of EFAs using principal component factorization with Varimax rotation was performed [125] until the psychometric properties were satisfactory. This analysis reduced the number of items to 21 under five sub-dimensions. The total variance of the measured variables explained 68.57% of the phenomenon. The alphas of the items were all significant, and those of the five sub-dimensions ranged from 0.74 to 0.91. Table 4 demonstrates the factor structure of the measurement tool. The discrepancy between theory and measurement can be justified by a high degree of proximity between items. Figure 4 presents the model resulting from step 3.

Table 4.

Factor structure of the IESM.

Figure 4.

IESM Model (Study 3).

From the outset, we had included as many items as possible, which explains the reduction from 86 to 21 items. The gap between theory and measurement can be justified by proximity between the items. For example, the only item in the Delight sub-dimension that proved to be significant grouped with those of Attachment. This result is supported by the literature which demonstrates that the affective dimension represents the experiential value derived by the intensity of the emotional connection, happiness, and the intrinsic level of arousal [110,128]. This affective congruence is reflected by emotional attachment, a variable therefore including delight. We joined the item to the Attachment sub-dimension. In addition, the last two behavioral levels (Creation and Devotion) formed a single factor. This can be attributed to the fact that for each of these two sub-categories, the follower actively and voluntarily engages in creating content about their influencer. In contrast, the Consumption sub-dimension represents passive engagement where there is no visible action from the follower. This finding is aligned with the literature on the divergence between passive and active engagement [73]. So, we docked the items under Creation. Regarding the cognitive dimension, the EFA only confirmed the Self-concept sub-dimension. This observation demonstrates the importance given by the follower to the congruence between the image projected by his influencer and his own, both in his eyes and in the eyes of others. It is therefore the main cognitive motif of IESM and implicitly encompasses Influence, Absorption and Attention.

4.4. Study 4: Confirmation of the Scale

The objective of step 4 is to confirm the validity and reliability of the tool. We performed a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) [125] to assess the goodness of fit of the theoretical model to the empirical data [129] and the validity of the construct [130]. The structural equation method (SEM) was also used to run a set of linear regressions and simultaneously test the manifest and latent variables [131].

A new sample of respondents was solicited via IG, FB, and LinkedIn. We used the same influencer agency as in the previous step. Claudie Mercier, a well-known influencer, and YouTuber in Quebec (@claudiemercier, 327,000 followers on IG as of 3 July 2023), made an IG story with a link leading to the questionnaire. We obtained 1491 questionnaires. In addition, we have requested the collaboration of the University so that it sends an email including the recruitment offer in its list (employees and students). The selection criteria as well as the flow of the questionnaire were identical to step 3. We obtained 1491 questionnaires. After eliminating those that did not meet the eligibility criteria, the final sample size of step 4 was 929 respondents (62% of questionnaires started).

4.4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Ninety-seven percent of respondents were women. This is due to the fact that Mercier was an influencer who shared the survey with her follower base. Of the 929 participants, 66% were in the 18–24 age range, 42% had an undergraduate degree, and 57% had an annual income of <$24,000. These statistics are consistent with the demographics of SM users, who predominantly visit IG [132,133]. Table 5 paints a portrait of the eight most mentioned influencers by respondents, ranging from 207 to 28 times. Of the nine proposed industries, those where identified influencers were active included lifestyle (35%), other (28%), fashion (11%), humor (6%) and cosmetics/beauty (4%).

Table 5.

Profile of the most popular influencers in the study.

4.4.2. First-Order Model

According to our theoretical conceptualization (Figure 4), the IESM scale must present a latent structure of a second-order model [134]. The sub-dimensions are first-order variables and are collectively represented by three second-order variables (COG, AFF, COMP). The first stage of step 4 is therefore a CFA on first-order latent variables. The data were analyzed using JMP Pro 16 software and suggested a good structure: a chi-square of 492.62 with 179 dl, which is within the prescribed thresholds [135]. The absolute indices were within the established criteria [103]. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.04 (<0.08), the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) was 0.03 (<0.08), and the revised goodness of fit index (GFI) was 0.96 (≥0.90). In addition, the comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.96 (≥0.90) was found to be satisfactory [104]. Finally, factor loadings for all items were significant, ranging from 0.84 to 0.68 (p ≤ 0.000).

4.4.3. Second-Order Model

Although the number of dimensions and sub-dimensions varies according to the tools identified during the literature review, most authors defend the multidimensionality of the concept (e.g., [22]. The creation of the second-order latent variables reflects the covariation between the first-order variables [136], and ensures that the estimated sub-dimensions define the larger, more abstract IESM construct [137]. However, moving to the next level requires a minimum of two sub-dimensions per dimension. Thus, only COMP (CONS, CONT, CRE) was a second-order variable (Figure 4). This observation reinforces the distinction between the engagement to an HB and a traditional brand in addition to supporting the relevance of the development of the tool.

The results of the second-order CFA suggested that the model had a good fit to the data. Both the RMSEA: 0.05 and CFI: 0.95 were above the prescribed thresholds. To ensure the quality of our model, we compared it with three alternative models: The null model [Model 1], the unidimensional model where all 21 items were forced to load on a single factor [Model 2], the model with five subdimensions [Model 3], and the model with one (COMP) and two subdimensions (SLFC, ATT) [Model 4]. Because of their nested nature, we used the maximum likelihood estimation method, which allows comparison of the models using the chi square [106]. The comparative results presented in Table 6 indicate that model 3 fits the data better than the competing models do. Therefore, this model was retained and the IESM scale is modeled by five dimensions (Figure 5).

Table 6.

Model comparison indices.

Figure 5.

Final IESM model (Study 4).

4.4.4. Construct Validity

According to Fornell and Larcker (1981) [138], convergent validity is established when the average variance extracted (AVE) of the measures of a construct is above the 50% threshold. All AVEs exceeded this percentage, which confirmed the convergent validity of the IESM. Next, we compared the AVEs of the variables with the correlation between the squared constructs. For each of the matched combinations, the AVE value exceeded the squared correlation. This proved the discriminant validity of the scale. Table 7 shows the indices of construct validity.

Table 7.

Construct validation indices.

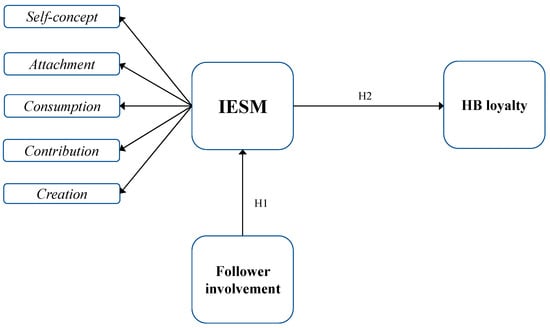

4.5. Step 5: Nomological Validity

Step 5 assesses the nomological validity of the scale by examining it within a network of conceptual relationships [139] focused on an antecedent and a consequence of IESM. Involvement is the antecedent most often mobilized in the conceptualization of engagement in marketing [82,140]. When followers engage with content on SM, the experience is described as a deep sense of involvement, often combined with excitement and/or pleasure [70]. Hence the following hypothesis:

H1.

Follower involvement has a positive and direct impact on IESM.

In addition, the literature affirms that loyalty is the primary outcome of engagement, for example in the SM context [36,140,141]. Moreover, engagement is considered a promising variable for predicting retention [24,142] the following hypothesis:

H2.

IESM has a positive and direct impact on HB loyalty.

The data were gathered from the previous set (sample 5). Figure 6 presents the nomological model tested. As expected, follower involvement had a significant impact on the IESM, thus supporting H1. The IESM also had a significant impact on subscriber HB loyalty, supporting H2.

Figure 6.

Nomological model of IESM.

The involvement and loyalty variables were included in a model, then a composite variable considering each of the average scores of the five dimensions was created to bring together the entire scale. Next, we examined hypothesized explanatory paths. As expected, follower involvement exerted a significant impact on IESM validating H1. IESM also had a significant impact on follower loyalty, validating the H2. Table 8 presents the confirmed structural trajectory estimates. Thus, the more the follower is involved, the higher his IESM and the higher his loyalty to his influencer.

Table 8.

Structural path estimates.

5. Discussion

The scientific literature offers several scales for measuring consumer engagement with an inanimate brand on SM. However, due to the distinctiveness of the HB (influencer), linked to being a living person,—more authentic than a traditional brand and acting actively and collaboratively with its followers [15,16,143]—the current measurement instruments were not applicable to our study context. Thus, the objective of this research was to conceptualize, develop, and validate a measurement scale specific to engagement with an influencer on SM (IG).

Validated in five separate studies, the IESM scale was found to be a second-order multidimensional construct. It assesses cognitive, affective, and behavioral characteristics of follower engagement simultaneously, without converging on common latent variables. This disconnects between theory and empirical results justifies the importance of developing this measurement tool.

In the scale purification step (Step 3), 230 followers rated their engagement with their chosen influencer. According to the AFE, IESM consisted of five dimensions, namely Self-Concept, Attachment, Consumption, Contribution and Creation. Data collected from another 929 followers (Step 4) corroborated these dimensions, which led to the creation of a 21-item scale. Next, nomological validity (Step 5) confirmed that the scale behaved as expected regarding the constructs that should be attached to it. To summarize, the responses of the 37 marketing experts and 1159 followers surveyed have contributed to the development of the IESM scale.

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5.1. Academic Contributions

This study provides a theoretical foundation that captures the interactive, personal, and social aspects of follower engagement. The results thus expand the knowledge base of relationship marketing and provide the first measurement scale for IESM. We also refined both the definition of a digital influencer and that of engagement with this HB. We have demonstrated that the engagement studied goes beyond observed behavior and involves dimensions inherent to psychology, such as self-concept and attachment [144]. The proposed conceptualization thus supports the three-dimensional nature of engagement: cognitive, affective, and behavioral [29,30,106]. It deepens the understanding of these dimensions by adding items and adapting them to investigation of influencers. Specifically, cognitive processing has previously been tested under the sub-dimensions of attention and absorption [30]. However, in IESM the cognitive component is represented by the follower’s self-concept, that is the dynamic and evaluative portrait that individuals develop of themselves during interactions with their social environment [145]. Followers integrate the identity signal that their influencer transmits into their self-concept to project a desired self-image [50]. This process influences their future attitudes and behaviors [146]. This can be explained by the fact that 66% of the respondents were aged between 18 and 24 and therefore at a stage of development conducive to the quest for their identification. Indeed, the identity formation cycle of young people is based on identity through an in-depth exploration of identification with engagements. To do this, they experiment with different social roles during a psychosocial moratorium granted by society [147]. Peer influence, especially through SMs, is a popular enforcer for this age group, as a means of making their voices heard, of self-esteem and of confirming their identity [148]. Therefore, focusing on the self-concept between the follower and the influencer provides avenues for increasing IESM.

Further, the affective component, i.e., the overall degree of affect positively linked to a brand [30], is often measured by enthusiasm and pleasure [22]. However, our study shows that affect is primarily mobilized by the measurement of attachment to the influencer. According to attachment theory [108], attachment is a specific emotionally charged bond between a person and an object, which happens to be a human in this case. Attachment is related to the need for social contact and for human interaction. The stronger the attachment, the higher the level of connection to the HB [149]. It is therefore easier to become attached to an influencer with whom one is in virtual contact on a daily basis than to a traditional brand. To this end, the initial model, the Affective dimension included three sub-dimensions and 34 items to finally present a dimension under five items. This confirms the unique nature of IESM, but also that this attachment is questionable. Respondents reported being strongly attached to their influencer, but is this a real attachment/engagement or is it rather mechanical, even that followers like and share out of habit? The ergonomics of SM facilitating engagement actions. This therefore opens the door to the possible correlation between engagement and the platform or the type of content broadcast. There are so many variables that can impact IESM. Finally, behavioral engagement is characterized by activity on SM that varies in intensity depending on the type of interaction with publications [72]. Our results confirmed and clarified the behavioral nature of engagement by adjusting the COBRA classification items to match behaviors toward an influencer.

To summarize, the IESM scale allows one to identify multiple facets of followers’ mental and behavioral patterns. This scale thus advances the scientific exploration surrounding an HB that is ubiquitous in consumers’ daily lives. Given that interpersonal relationships are central to the engagement measured by the tool, the scale could also be useful to other disciplines that are interested in human relationships (e.g., sociology).

5.2. Managerial Implications

Strategic management of IESM is instrumental to the marketing approach for influencers managers and influencers. The tool can serve to identify the strongest dimensions of engagement, and the ones on which to focus in order to increase the IESM of a particular influencer. The measurement scale will therefore facilitate the development and evaluation of new communication strategies on IG.

Consistent with previous research, we have noted that some followers tend to interpret their self-concept in terms of their preferred brand [33]. Whether it be because the follower perceives the influencer as a role model or because interacting publicly with the influencer allows the follower to improve the way they are perceived by others, congruence between the user’s image and that of the influencer increases IESM. However, this level of engagement varies considerably from one follower to another. Hence the importance of using the scale and adjusting strategies based on the actual level of engagement with each of the five proposed dimensions. Especially since the study participants recognized the influencer’s ability to spur their thoughts and actions, particularly when their level of attachment is high [150]. In addition, measuring IESM can justify the fees that influencers charge to the brands they endorse.

Further, social belonging encourages participation, and SM are adept at cultivating this feeling through online communities [151]. These communities promote social interaction, engagement, and brand loyalty [152,153]. Therefore, influencers who engage with their followers and encourage them to react to each other increase positive word-of-mouth about them, along with follower engagement rate.

In short, the proposed scale captures follower IESM holistically. Without this tool, managers will continue to measure behavioral engagement exclusively, and rely solely on the size of the follower base as an indicator of influence. This approach does not take into account the complexity and subtleties of IESM highlighted in this research.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

This study has limitations that offer avenues for future research. First, IESM was studied solely through IG. It would be interesting to test the scale on other social platforms (e.g., TikTok) and analyze whether the instrument is generalizable or to identify discrepancies across platforms. Second, despite the large number of respondents (1159), the sample in Steps 4 and 5 was 97% female, of whom 66% were in the 18–24 age range. This is explained by the fact that it was women’s influencers in their twenties who shared the questionnaire with their followers. Although this sample does not allow for extrapolation of the results, this has little impact on the development of measurement scales. However, it would be interesting to do a comparative analysis of IESM across various ages and genders and observe the results for each of the scale dimensions. We could thus learn more about the content to emphasize based on sociodemographic criteria and optimize engagement. Second, we can believe that an influencer in the fashion industry where looks are ubiquitous would elicit higher self-concept scores. In doing so, it would have been interesting to analyze the motivation of the follower towards his influencer. Does the industry or type of product represented affect the IESM?

Further, respondents mentioned different types of influencers based on the number of followers to their accounts. Therefore, it would be relevant to conduct a study to test the effect of influencer category (e.g., nano, mega) on IESM and to analyze the possible effect of the type of self-aspiration (actual, ideal, future) towards the influencer. In addition, the definition of an influencer states that they could share the interests of a third party by promoting a brand or simply recounting a lived experience to their network. Focusing on engagement with an influencer as an HB as opposed to a brand, they endorse could prompt reflection on the sociological and non-pecuniary orientation of this relationship.

The accumulated knowledge presented in this article can further the theoretical development of the HB and pave the way for additional research on the topic. Indeed, future studies are needed to enrich the literature and to refine the concept of engagement with a digital influencer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; methodology; software: N.L.; validation F.P.; formal analysis; investigation; resources; data curation; writing—original draft preparation; writing—review and editing; visualization: N.L., supervision F.P.; project administration; funding acquisition: N.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council: Doctoral funding And the APC was funded by Frank Pons.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of LAVAL UNIVERSITY (2019-389/23-01-2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Key quotes from in-depth interviews.

Table A1.

Key quotes from in-depth interviews.

| ID | Gender/Age | Influencer |

|---|---|---|

| A3 | F (30) | “It’s someone who has a certain number of followers, but the number isn’t necessarily that crucial as the follower engagement. It’s someone who wants to be like her or like him. A bit like a model, depending on the sphere: fashion, sport, beauty, travel. And the influencer can influence people to buy certain products, do certain things, because of their followers’ level of engagement.” |

| E7 | F (30) | “There are different types. There are those who will get some benefit from a product or service they have promoted. There can also be micro-influencers, in the sense that someone in my environment may have enjoyed a product or service and wants to share the news with my network. That, I like, it’s great because it’s a stamp of approval from someone I trust.” |

| A5 | M (31) | “I think there are two aspects. First, I’d say it’s a kind of conformity. Let’s say the person sees themselves in that person. Then the second is more about trust. Just like when you buy products or services. You’ll go back to the same companies because you have a good experience. So that’s pretty much what influence is about. Compliance and resemblance, and then the trust and service aspect. You’re satisfied with what the influencer says.” |

| ID | Gender/age | Engagement |

| A2 | M (50) | “The ultimate engagement is when you are going to do the transaction that the other is promoting and influencing you to do.” |

| E13 | F (29) | “There are several categories of engagement. Active and passive engagement. A passive person will watch, but never act. [...] In the sense that they see, it’s nice content, but it’s never going to end up making the person act over a year, two years, five years. It’s not voyeurism, but almost. You have the other portion: active engagement. Let’s say, I’m an influencer from Australia, and in her morning routine, she uses a cream. I screenshot it, and I went and bought it.” |

| E9 | M (29) | “If there’s a gesture towards the influencer. So maybe a Like or a share, a comment. Or even just consulting information and then sharing it, on your own, in discussion, I think it becomes a share as such.” |

References

- Fournier, S. Consumers and Their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinerean, S.; Opreana, A. Consumer Engagement in Online Settings: Conceptualization and Validation of Measurement Scales. Expert J. Mark. 2015, 3, 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mirbagheri, S.; Najmi, M. Consumers’ Engagement with Social Media Activation Campaigns: Construct Conceptualization and Scale Development: Mirbagheri and Najmi. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Demystifying Customer Brand Engagement: Exploring the Loyalty Nexus. J. Mark. Manag. 2011, 27, 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laer, T.; De Ruyter, K.; Cox, D. A Walk in Customers’ Shoes: How Attentional Bias Modification Affects Ownership of Integrity-Violating Social Media Posts. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Conduit, J.; Brodie, R.J. Strategic Drivers, Anticipated and Unanticipated Outcomes of Customer Engagement. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Rajan, B.; Gupta, S.; Pozza, I.D. Customer Engagement in Service. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audreze, A.; de Kervile, G.; Moulard, J.G. Authenticity under Threat When Social Media Influencers Need to Go beyond Passion. In Proceedings of the 2017 Global Fashion Management Conference, Vienna, Austria, 6–9 July 2017; pp. 170–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, C.M.; Pounders, K.R. Transforming Celebrities through Social Media: The Role of Authenticity and Emotional Attachment. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque, N.; Pons, F. The Human Brand: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. J. Cust. Behav. 2020, 19, 143–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, M.A.C.; Sarfati, G. The Millennials Luxury Brand Engagement on Social Media: A Comparative Study of Brazilians and Italians. Rev. Int. Bus. 2019, 14, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, M.; Xu, J. Business Intelligence in Blogs: Understanding Consumer Interactions and Communities. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 1189–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reade, J. Keeping It Raw on the ‘gram: Authenticity, Relatability, and Digital Intimacy in Fitness Cultures on Instagram. New Media Soc. 2021, 23, 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the Credibility of Online Celebrities’ Instagram Profiles in Influencing the Purchase Decisions of Young Female Users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R.H.; Ferreira, J.B.; de Freitas, A.S.; Ramos, F.L. The Effects of Social Media Opinion Leaders’ Recommendations on Followers’ Intention to Buy. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2018, 20, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susarla, A.; Oh, J.H.; Tan, Y. Influentials, Imitables, or Susceptibles? Virality and Word-of-Mouth Conversations in Online Social Networks. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.T.; Chen, H.L.; Cheng, C.Y. Internationalization and Firm Performance of SMEs: The Moderating Effects of CEO Attributes. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube Bloggers Promote It, Why Should I Buy? How Credibility and Parasocial Interaction Influence Purchase Intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunoǧlu, E.; Misci Kip, S. Brand Communication Through Digital Influencers: Leveraging Blogger Engagement. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesiloglu, S.; Costello, J. Influencer Marketing: Building Brand Communities and Engagement; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, N.; Hachey, A.; Pergelova, A. No Filter: Navigating Well-Being in Troubled Times as Social Media Influencers. J. Mark. Manag. 2023, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Capturing Consumer Engagement: Duality, Dimensionality and Measurement. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, A. The Constant Customer. Bus. J. 2001. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/businessjournal/745/constant-customer.aspx (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Bowden, J. The Process of Customer Engagement: A Conceptual Framework. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schau, H.J.; Muñiz, A.M.; Arnould, E.J. How Brand Community Practices Create Value. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Christodoulides, G.; Dabrowski, D. Measuring Consumers’ Engagement with Brand-Related Social-Media Content: Development and Validation of a Scale That Identifies Levels of Social-Media Engagement with Brands. J. Advert. Res. 2016, 56, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhlovu, T.; Maree, T. Consumer Brand Engagement: Refined Measurement Scales for Product and Service Contexts. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 146, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Jafari, A.; O’Gorman, K. Keeping Your Audience: Presenting a Visitor Engagement Scale. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Juric, B.; Ilic, A. Customer Engagement: Conceptual Domain, Fundamental Propositions, and Implications for Research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W.; Wood, B.P. Followers’ Engagement with Instagram Influencers: The Role of Influencers’ Content and Engagement Strategy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, E.A.; Hemetsberger, A. “Hopelessly Devoted to You”—Towards an Extended Conceptualization of Consumer Devotion. In Advances in Consumer Research; Association for Consumer Research: Duluth, MN, USA, 2007; Volume 34, pp. 194–199. [Google Scholar]

- Sprott, D.; Czellar, S.; Spangenberg, E. The Importance of a General Measure of Brand Engagement on Market Behavior: Development and Validation of a Scale. J. Mark. Res. 2009, 46, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solem, B.A.A.; Pedersen, P.E. The Role of Customer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualisation, Measurement, Antecedents, and Outcomes. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2017, 10, 223–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obilo, O.O.; Chefor, E.; Saleh, A. Revisiting the Consumer Brand Engagement Concept. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 126, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A. A Higher-Order Model of Consumer Brand Engagement and Its Impact on Loyalty Intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Sarstedt, M.; Menidjel, C.; Sprott, D.E.; Urbonavicius, S. Hallmarks and Potential Pitfalls of Customer- and Consumer Engagement Scales: A Systematic Review. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault-Labbé, A.; Dubé, L. Mieux Comprendre l’engagement Psychologique: Revue Théorique et Proposition d’un Modèle Intégratif. Les Cah. Int. De Psychol. Soc. 2009, 81, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer Engagement Behavior: Theoretical Foundations and Research Directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.; Zhou, Z.; Kim, W.G. Destination Brand Image and Destination Brand Choice in the Context of Health Crisis: Scale Development. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 29, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algesheimer, R.; Dholakia, U.M.; Herrmann, A. The Social Influence of Brand Community: Evidence from European Car Clubs. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, B.J.; Malthouse, E.C.; Schaedel, U. An Experimental Study of the Relationship between Online Engagement and Advertising Effectiveness. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work Engagement: A Quantitative Review and Test of Its Relations with Task and Contextual Performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. To Be Fully There: Psychological Presence at Work. Hum. Relat. 1992, 45, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, C.E.; Hair, J.F.; Zambaldi, F.; Ponchio, M.C. Consumer Brand Engagement Concept and Measurement: Toward a Refined Approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, E. Engaging Consumers in Esthetic Offerings: Conceptualizing and Developing a Measure for Arts Engagement. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2015, 20, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Perdue, R.R. Developing a Multi-Dimensional Measure of Hotel Brand Customers’ Online Engagement Behaviors to Capture Non-Transactional Value. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.D. A Scale of Consumer Engagement. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Alabama, Huntsville, AL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention; HarperColl: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-Concept in Critical Review Consumer Behavior. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schembri, S.; Merrilees, B.; Kristiansen, S. Brand Consumption and Narrative of the Self. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.; Dholakia, U.M. Antecedents and Purchase Consequences of Customer Participation in Small Group Brand Communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2006, 23, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Hayagreeva, R.; Glynn, M.A. Understanding the Bond of Identification: An Investigation of Its Correlates Among Art Museum Members. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.K.F.; King, C.; Sparks, B. Customer Engagement with Tourism Brands: Scale Development and Validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, B.J.; Issac, M.S.; Malthouse, E.C. Taking the Customer’s Point-of-View: Engagement or Satisfaction; Marketing Science Institute Work Paper Series; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 13–102. [Google Scholar]

- Dielh, S. Brand Attachment; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bergami, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. Self-Categorization, Affective Commitment, and Group Self-Esteem as Distinct Aspects of Social Identity in the Organization. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 39, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault-Labbé, A.; Dubé, L. Engagement, Surengagement et Sous-Engagement Académiques Au Collégial: Pour Mieux Comprendre Le Bien-Être Des Étudiants. Rev. Des Sci. De L’éducation 2008, 34, 729–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brault-Labbé, A.; Dubé, L. Engagement Scolaire, Bien-Être Personnel et Autodétermination Chez Des Étudiants à l’université. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2010, 42, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, B.; Kunz, W. How to Transform Consumers into sans of Your Brand. J. Serv. Manag. 2012, 23, 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, D.W. The Buying Impulse. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilicic, J.; Baxter, S.M.; Kulczynski, A. The Impact of Age on Consumer Attachment to Celebrities and Endorsed Brand Attachment. J. Brand Manag. 2016, 23, 273–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jillapalli, R.K.; Wilcox, J.B. Professor Brand Advocacy: Do Brand Relationships Matter? J. Mark. Educ. 2010, 32, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K. Celebrity Endorsements: Influence of a Product-Endorser Match on Millennials Attitudes and Purchase Intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumöl, U.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jung, R. Dynamics of Customer Interaction on Social Media Platforms. Electron. Mark. 2016, 26, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Kim, W. Do Your Social Media Lead You to Make Social Deal Purchases? Consumer-Generated Social Referrals for Sales via Social Commerce. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C. Communicative Intimacies: Influencers and Perceived Interconnectedness. Ada A J. Gend. New Media Technol. 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, M.D.R.; Del Olmo Arriaga, J.L.; Andreu, D. The Interaction of Instagram Followers in the Fast Fashion Sector: The Case of Hennes and Mauritz (H&M). J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2019, 10, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C. User Engagement in Social Media—An Explorative Study of Swedish Fashion Brands. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syrdal, H.A.; Briggs, E. Engagement with Social Media Content: A Qualitative Exploration. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2018, 26, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzak, F.; Makarem, S.; Jae, H. Design Benefits, Emotional Responses, and Brand Engagement. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2014, 23, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutinga, D.G.; Moorman, M.; Smit, E.G. Introducing COBRAs Exploring Motivations for Brand-Related Social Medias Use. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 13–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainous, J.; Abbott, J.P.; Wagner, K.M. Active vs. Passive Social Media Engagement with Critical Information: Protest Behavior in Two Asian Countries. Int. J. Press/Politics 2021, 26, 464–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G. Understanding the Appeal of User-Generated Media: A Uses and Gratification Perspective. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Pearo, L.K. A Social Influence Model of Consumer Participation in Network- and Small-Group-Based Virtual Communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic Word-of-Mouth via Consumer-Opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schivinski, B.; Dabrowski, D. The Impact of Brand Communication on Brand Equity through Facebook. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuignier, R. Place Branding & Place Marketing 1976–2016: A Multidisciplinary Literature Review. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2017, 14, 447–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Verčič, D. Generic Charisma—Conceptualization and Measurement. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig Lefebvre, R.; Tada, Y.; Hilfiker, S.W.; Baur, C. The Assessment of User Engagement with eHealth Content: The eHealth Engagement Scale. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2010, 15, 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, H.; Toms, E. The Development and Evaluation of a Survey to Measure User Engagement. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2010, 61, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Lee, M.; Jin, X. Customer Engagement in an Online Social Platform: A Conceptual Model and Scale Development. In Proceedings of the Thirty Second International Conference on Information Systems, Shanghai, China, 4–7 December 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida, M.; Gordon, B.; Nakazawa, M.; Biscaia, R. Conceptualization and Measurement of Fan Engagement: Empirical Evidence from a Professional Sport Context. J. Sport Manag. 2014, 28, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, S.D.; Beatty, S.E.; Dalela, V.; Morgan, R.M. A Generalized, Multidimensional Scale for Measuring Customer Engagement. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2014, 22, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldus, B.J.; Voorhees, C.; Calantone, R. Online Brand Community Engagement Scale. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopp, T.; Gallicano, T.D. Development and Test of a Multidimensional Scale of Blog Engagement. J. Public Relat. Res. 2016, 28, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Malthouse, E.C.; Block, M.P. Sounds of Music: Exploring Consumers’ Musical Engagement. J. Consum. Mark. 2016, 33, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, B.J.; Isaac, M.S.; Malthouse, E.C. How to Capture Consumer Experiences: A Context-Specific Approach to Measuring Engagement: Predicting Consumer Behavior Across Qualitatively Different Experiences. J. Advert. Res. 2016, 56, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R. Understanding Customer Engagement and Loyalty: A Case of Mobile Devices for Shopping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 32, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paruthi, M.; Kaur, H. Scale Development and Validation for Measuring Online Engagement. J. Internet Commer. 2017, 16, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrigan, P.; Evers, U.; Miles, M.; Daly, T. Customer Engagement with Tourism Social Media Brands. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.; Morse, D.T.; Hood, K.; Walker, C. Measuring Alcohol Marketing Engagement: The Development and Psychometric Properties of the Alcohol Marketing Engagement Scale. J. Appl. Meas. 2017, 18, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M. How Television Viewers Use Social Media to Engage with Programming: The Social Engagement Scale Development and Validation. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2018, 62, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Choi, H.-S.C. Developing and Validating a Multidimensional Tourist Engagement Scale (TES). Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 469–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-I.; Chen, M.-C.; Shih, Y.-W. Customer Engagement Behaviours in a Social Media Context Revisited: Using Both the Formative Measurement Model and Text Mining Techniques. J. Mark. Manag. 2022, 38, 740–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S.; Eckhardt, G. Managing the Human in Human Brands. GfK-Mark. Intell. Rev. 2018, 10, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.; Schau, H.J. The Ties That Bind: Consumer Engagement and Transference with a Human Brand. In Proceedings of the ACR North American Advances, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 6–9 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, D.; Wohl, R.R. Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukachinsky, R. Para-Romantic Love and Para-Friendships: Development and Assessment of a Multiple-Parasocial Relationships Scale. Am. J. Media Psychol. 2010, 3, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Reinikainen, H.; Munnukka, J.; Maity, D.; Luoma-aho, D. ‘You Really Are a Great Big Sister’—Parasocial Relationships, Credibility, and the Moderating Role of Audience Comments in Influencer Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, M.-A. L’empire de Maripier Morin s’écroule. J. De Montréal 2020. Available online: https://www.journaldemontreal.com/2020/07/09/maripier-morin-met-ses-activites-professionnelles-sur-la-glace (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Speed, R.; Butler, P.; Collins, N. Human Branding in Political Marketing: Applying Contemporary Branding Thought to Political Parties and Their Leaders. J. Political Mark. 2015, 14, 129–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D. Exploring Customer Brand Engagement: Definition and Themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Erich, J. Brand Leadership; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carah, N.; Shaul, M. Brands and Instagram: Point, Tap, Swipe, Glance. Mob. Media Commun. 2016, 4, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Ilic, A.; Juric, B.; Hollebeek, L.D. Consumer Engagement in a Virtual Brand Community: An Exploratory Analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Park, W.C.; Whan Park, C. The Ties That Bind: Measuring the Strength of Consumers’ Emotional Attachments to Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Disruption of Affectional Bonds and Its Effects on Behavior. Canada’s Ment. Health Suppl. 1969, 59, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, P.; Ting, Y.; De Ruyter, K. Understanding Customer Engagement in Services. In Proceedings of the ANZMAC Conference: Understanding customer engagement in services, Brisbane, Australia, 4–6 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mollen, A.; Wilson, H. Engagement, Telepresence and Interactivity in Online Consumer Experience: Reconciling Scholastic and Managerial Perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, K.A.; Bristol, T.; Brashaw, R.E. A Conceptual Approach to Classifying Sports Fans. J. Serv. Mark. 1999, 13, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojkov, K. 29 Instagram Statistics for Marketing in 2023. EmbedSocial 2023. Available online: https://embedsocial.com/blog/instagram-statistics/#:~:text=64.9%25%20of%20Instagram%20content%20is%20photo%2Dbased&text=Instagram%20Business%20account%20benchmark%20statistics,serving%20it%20to%20their%20audience (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Iqbal, M. Instagram Revenue and Usage Statistics (2023). Bus. Apps. 2023. Available online: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/instagram-statistics/ (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Hines, K. Social Media Engagement Rates Dropping Across Top Networks. Search Engine J. 2023. Available online: https://www.searchenginejournal.com/social-media-engagement-report/481911/#close (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E. Instagram Fashionistas, Luxury Visual Image Strategies and Vanity. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2019, 29, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, K. 90% of Social Media Influencers Are Active on Instagram: Study. Spiceworks 2023. Available online: https://www.spiceworks.com/marketing/content-marketing/articles/social-media-influencers-are-active-on-instagram/#:~:text=Instagram%20Emerges%20the%20Top%20Platform%20for%20Influencers&text=According%20to%20the%20study%2C%2093,post%20content%20on%20several%20platforms (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Soffar, H. What Are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Instagram? Online Sci. 2022. Available online: https://www.online-sciences.com/technology/what-are-the-advantages-and-disadvantages-of-using-instagram/#:~:text=It%20increases%20artistic%20ability%20by,family%20in%20an%20original%20way (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Churchill, G. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahi, L.; Melghagh, M. Étude Empirique Sur Le Rôle Des Influenceurs Digitaux Dans La Stratégie Marketing Digitale. Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2020, 3, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Pagani, M.; Hofacker, C.F.; Goldsmith, R.E. The Influence of Personality on Active and Passive Use of Social Networking Sites. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, C.; Kwahk, K. Examining the Determinants of the Intention of Continued Instagram Usage: Focused on the Moderating Effect of the Gender. J. Korea Soc. Digit. Ind. Inf. Manag. 2016, 12, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Bearden, W.O.; Netemeyer, R.G. Handbook of Marketing Scales: Multi-Item Measures for Marketing and Consumer Behavior Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall International: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrongiello, C. De l’empowerment à l’engagement Du Client Sur Les Plateformes En Ligne: Ou Comment Favoriser l’activité Des Clients Sur Internet. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Grenoble, Grenoble, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wacheux, F.; Roussel, P. Management des Ressources Humaines: Méthodes de Recherche en Sciences Humaines et Sociales; De Boeck Supérieur: Vlaams-Brabant, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carricano, M.; Poujol, F.; Bertrandias, L.; Carricano, M. Analyse de Données Avec SPSS; Pearson Education: Paris, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, M.; Laroche, M.; Pons, F.; Kastoun, R. Acculturation and Consumption: Textures of Cultural Adaptation. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2009, 33, 196–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyris, Y.A.; Wang, Z.; Kim, Y.; Yin, Z. The Effects of Visual Congruence on Increasing Consumers’ Brand Engagement: An Empirical Investigation of Influencer Marketing on Instagram Using Deep-Learning Algorithms for Automatic Image Classification. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 112, 106443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, S.C. Influencer Tiers: How Different Categories of Influencers Impact the Attitude of Young Portuguese Women. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Católica Portugues, Lisbon, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rosel, J.; Plewis, I. Longitudinal Data Analysis with Structural Equations. Methodology 2008, 4, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, R.E. On Adjusting the Pearson Chi-Square Statistic for Clustered Sampling. In ASA Proceedings of the Social Statistics Section; American Statistical Association: Boston, MA, USA, 1979; pp. 402–406. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, M.O.; Price, L.L. Differentiating between Cognitive and Sensory Innovativeness: Concepts, Measurement, and Implications. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 20, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, P.; Durrieu, F.; Campoy, E.; El Akremi, A. Méthodes d’équations Structurelles: Recherche et Applications En Gestion; Recherche en gestion; Economica: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra Marketing Research and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper Titan, K.; Bearden, W.O.; Hunter, G. Consumers’ Need for Uniqueness: Scale Developpement and Validation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 50–66. [Google Scholar]

- Leckie, C.; Nyadzayo, M.W.; Johnson, L.W. Antecedents of Consumer Brand Engagement and Brand Loyalty. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 558–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer Engagement in Online Brand Communities: A Social Media Perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, J. Customer Engagement: A Framework for Assessing Customer-Brand Relationships: The Case of the Restaurant Industry. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2009, 18, 574–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Jose-Cabezudo, R.; Camarero-Izquierdo, C.; Rodriguez-Pinto, J. En Busca de Los Evangelizadores Digitales: Por Qué Las Empresas Deben Identificar y Cuidar a Los Usuários Más Activos de Los Espacios de Opiniones Online. Universia Bus. Rev. 2012, 35, 14–31. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, P.; Ric, F. Psychologie Sociale: Approches Du Sujet Social et Des Relations Interpersonnelles; Éditions Bréal: Paris, France, 1996; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Héroux, L.; Farrell, M. Le développement du concept de soi chez les enfants de 5 à 8 ans. Rev. Sci. L’éducation 2009, 11, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Levy, S.J. Symbols for Sale. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1959, 37, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Lannegrand-Willems, L. Le développement de l’identité à l’adolescence: Quels apports des domaines vocationnels et professionnels? Enfance 2012, 3, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrada, A.; Sahbani, S.; Benamar, M. Analyse de l’influence du marketing de contenu à travers les médias sociaux sur l’attachement à la marque. Rev. Marocaine De Rech. En Manag. Et Mark. 2017, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M. Human Brands: Investigating Antecedents to Consumers’ Strong Attachments to Celebrities. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Z.; Ali, S. Human Brands: Investigating Antecedents to Consumers’ Strong Attachment to Celebrities. Rev. Integr. Bus. Econ. Res. 2013, 2, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Helme-Guizon, A.; Magnoni, F. Les marques sont mes amies sur Facebook: Vers une typologie de fans basée sur la relation à la marque et le sentiment d’appartenance. Rev. Française Du Mark. 2013, 243, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.; Olfman, L.; Ko, I.; Koh, J.; Kim, K. The Influence of Online Brand Community Characteristics on Community Commitment and Brand Loyalty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2015, 12, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]