Do Electronic Coupon-Using Behaviors Make Men Womanish? The Effect of the Coupon–Feminine Stereotype

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. E-Coupon-Using Behaviors

2.2. Self-Congruence and Gender Identity

2.3. S-O-R Theory

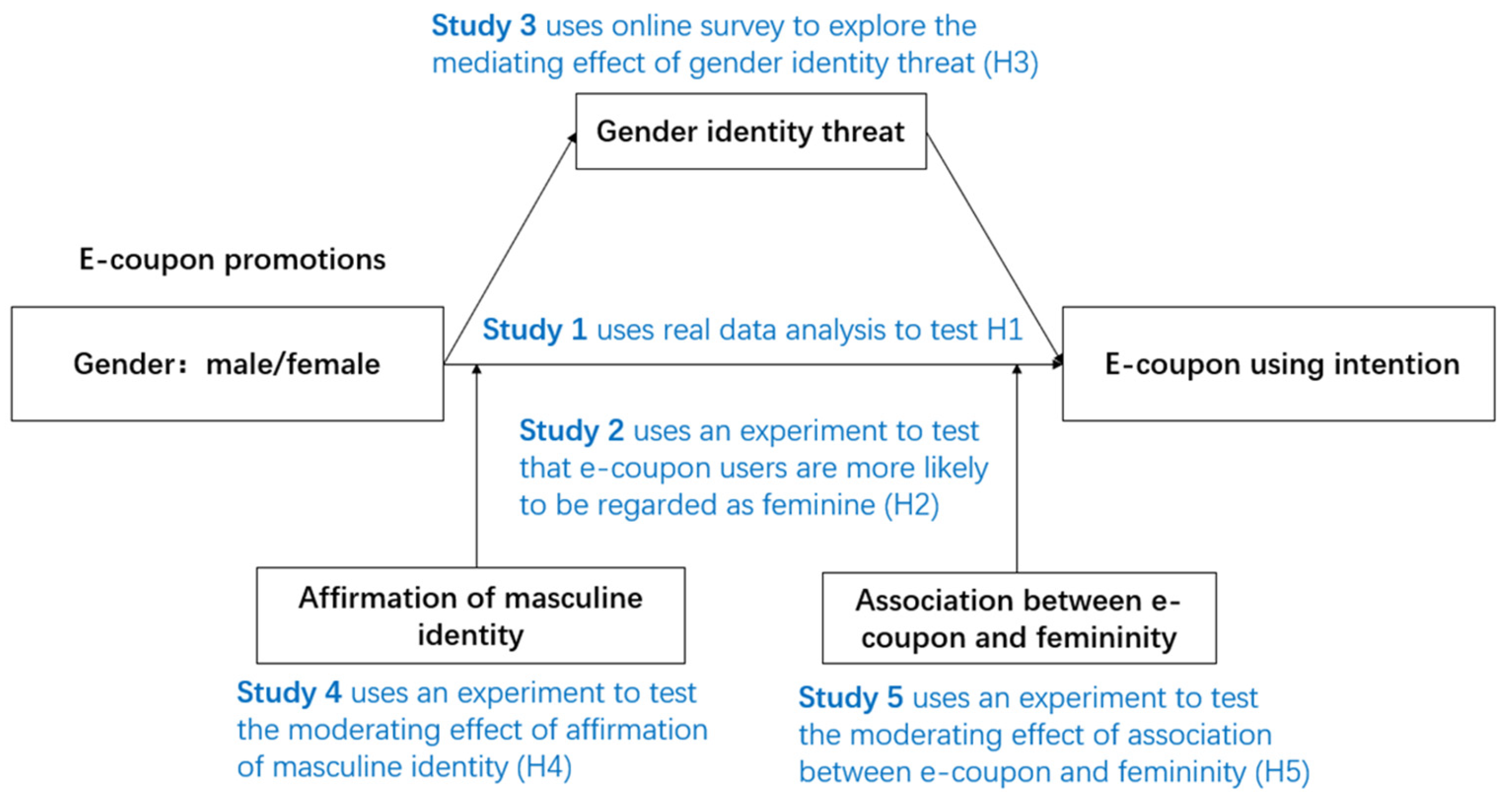

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Gender Differences in E-Coupon Usage and the Coupon–Feminine Stereotype

3.2. Mediating the Effect of Gender Identity Threat

3.3. Moderating Effects

4. Studies and Results

4.1. Study 1: The Gender Difference in E-Coupon Usage

4.1.1. Data

4.1.2. Analysis and Results

4.1.3. Discussion

4.2. Study 2: E-Coupon Users Are Perceived to Be More Feminine

4.2.1. Method

4.2.2. Results

4.2.3. Discussion

4.3. Study 3: The Role of Gender Identity Threat

4.3.1. Method

4.3.2. Results

4.3.3. Discussion

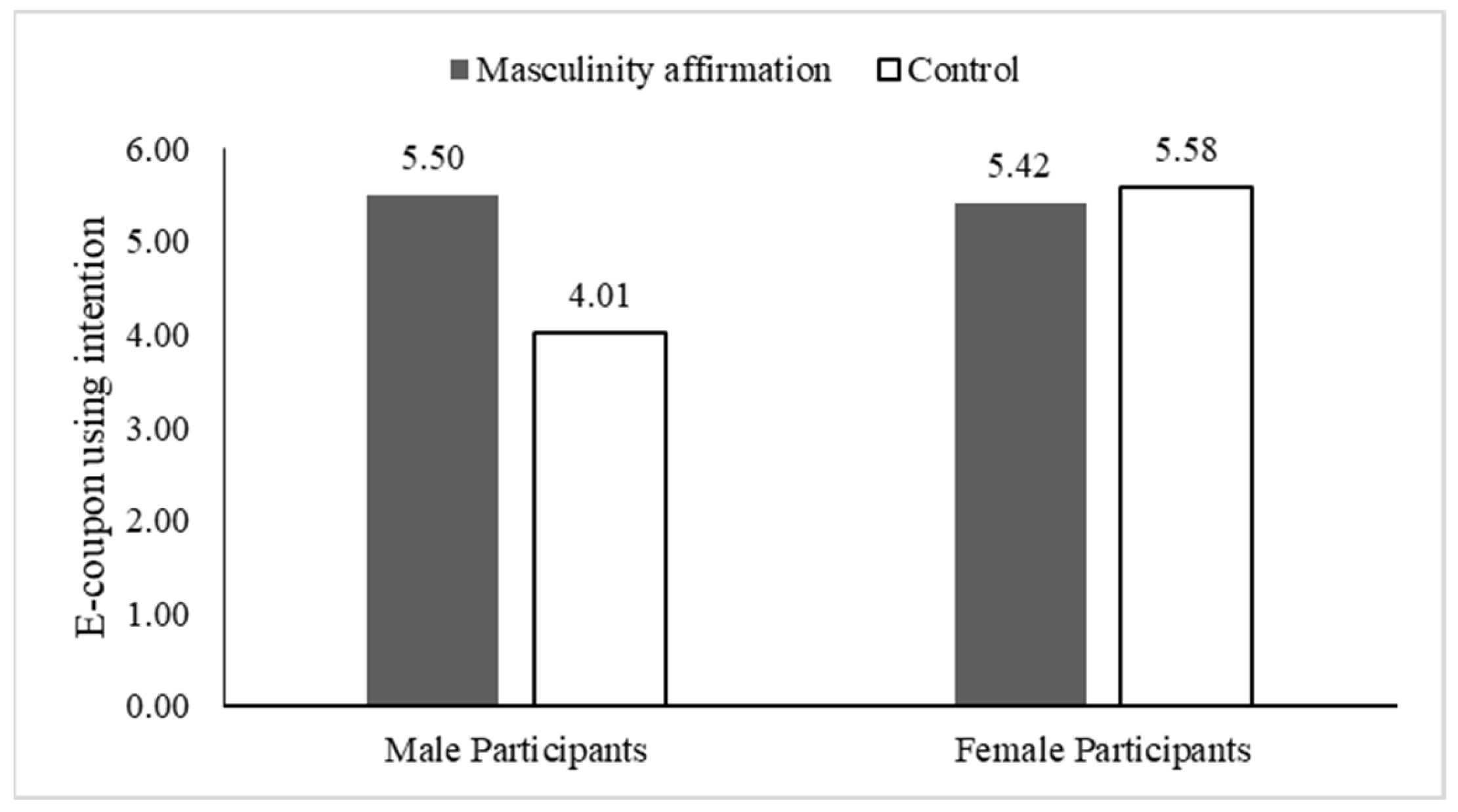

4.4. Study 4: Affirmation of Masculine Identity

4.4.1. Method

4.4.2. Results

4.4.3. Discussion

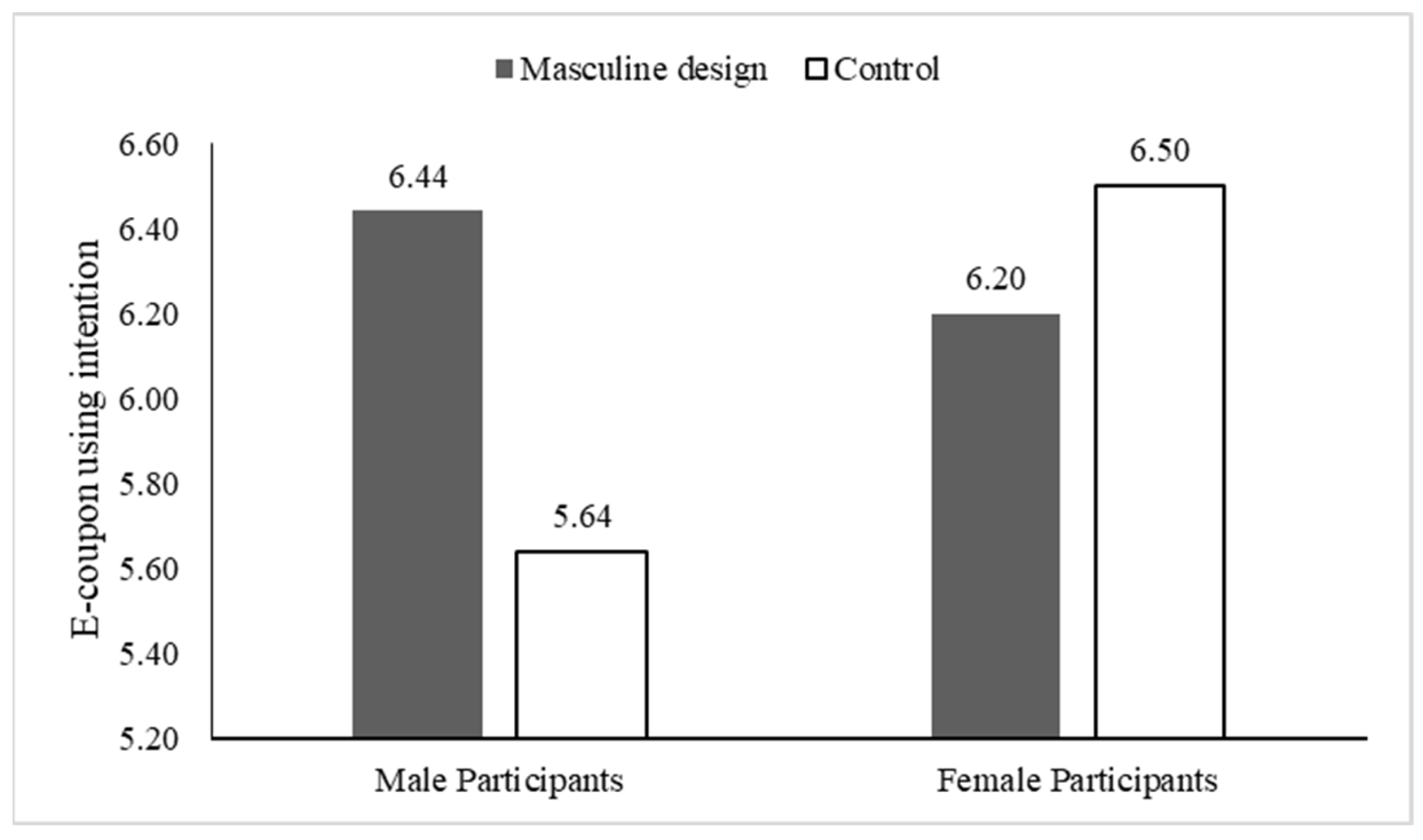

4.5. Study 5: Changing the E-Coupon Design to Weaken Feminine Associations

4.5.1. Method

4.5.2. Results

4.5.3. Discussion

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

5.3. Managerial Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Data Collection Procedure | Independent/Mediating/Moderating Variables | Dependent Variable | Main Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Data were collected from an e-coupon acquisition platform. | IV: Gender; Moderator: Public. | Coupon-using behavior | Men are less likely than women to use e-coupons; men are more likely to prevent e-coupon usage in a public versus a private context. |

| Study 2 | The experiment recruited 136 students from universities. | IV: E-coupon-using behavior of the target consumer L (yes vs. no). | Femininity/masculinity index | E-coupon users are more likely to be perceived as more feminine. |

| Study 3 | A total of 122 participants from an online survey. | IV: Gender; Mediator: Gender identity threat. | Coupon-using intention | Gender identity threat mediates the effect of gender on e-coupon-using intention. |

| Study 4 | The experiment recruited 120 participants from an online website. | IV: Gender; Moderator: Affirmation of masculine identity. | Coupon-using intention; coupon-using behavior | When participants’ masculinity has been affirmed, men are more likely to show increased e-coupon-using intention, while women show no difference. |

| Study 5 | The experiment recruited 160 participants from the website. | IV: Gender; Moderator: Association between e-coupon and femininity. | Coupon-using intention | When the association between e-coupons and femininity is weakened, men are more likely to show increased e-coupon-using intention. |

Appendix B

| Items | Factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Masculinity Index | Femininity Index | |

| Feminine | −0.176 | 0.792 |

| Soft | 0.099 | 0.774 |

| Gentle | 0.248 | 0.773 |

| Sensitive | −0.186 | 0.854 |

| Masculine | 0.786 | −0.260 |

| Macho | 0.870 | −0.006 |

| Manly | 0.877 | 0.168 |

| Aggressive | 0.834 | 0.043 |

References

- Fisher, G.; McGranaghan, M.; Liaukonyte, J.; Wilbur, K.C. Price promotions, beneficiary framing, and mental accounting. In Quantitative Marketing and Economics; Spring: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, C.; Zhao, P. Mobile coupon acquisition and redemption for restaurants: The effects of store clusters as a double-edged sword. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravula, P.; Bhatnagar, A.; Ghose, S. Antecedents and consequences of cross-effects: An empirical analysis of omni-coupons. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2020, 37, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, W.; Wen, K.; Zhang, D. Who is better for single and double coupon promotion? Comparison from dual-channel and two-period. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 2079–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, J.; Qiu, J. Impacts of Platform’s Omnichannel Coupons on Multichannel Suppliers. J. Syst. Sci. Syst. Eng. 2023, 32, 71–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.L.; Choeh, J.Y. Motivations for obtaining and redeeming coupons from a coupon app: Customer value perspective. J. Thero. Appl. El. Comm. 2021, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ladhari, R.; Hudon, T.; Massa, E.; Souiden, N.; Timmermans, H. The determinants of women’s redemption of geo-targeted m-coupons. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, P.; Zamudio, C. Scanning for discounts: Examining the redemption of competing mobile coupons. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 964–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayal, P.; Pandey, N.; Paul, J. Examining m-coupon redemption intention among consumers: A moderated moderated-mediation and conditional model. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2021, 57, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akman, Y.; Türkmen, H.G. A study on customer perceptions and attitudes towards digital coupon. J. Bus. Innov. Gov. 2021, 4, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Teng, L.; Yu, Y.; Yu, X. The Effect of Online Information Sources on Purchase Intentions between Consumers with High and Low Susceptibility to Informational Influence. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Zhao, X.; Chau, P.Y.; Tang, Q. Roles of perceived value and individual differences in the acceptance of mobile coupon applications. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.; Im, H. Determinants of mobile coupon service adoption: Assessment of gender difference. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. 2014, 42, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.N.; Kwon, Y.J. Demographics in sales promotion proneness: A socio-cultural approach. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Fitzsimons, G., Morwitz, V., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 2007; Volume 34, pp. 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. In-Store Mobile Commerce during the 2012 Holiday Shopping Season. Available online: www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/in-store-mobile-commerce.aspx (accessed on 24 September 2013).

- Harmon, S.K.; Hill, C.J. Gender and coupon use. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2003, 12, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Ha, Y. Is this mobile coupon worth my private information? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2015, 9, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.A.H.; Alothman, B.; Alhoshan, L. Impact of Gender, Age and Income on Consumers’ Purchasing Responsiveness to Free-Product Samples. Res. J. Int. Stud. 2013, 26, 83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Blattberg, R.; Buesing, T.; Peacock, P.; Sen, S. Identifying the deal prone segment. J. Mark. Res. 1978, 15, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.M.; Liou, J.H.; Ni, C.Y. Diffusing mobile coupons with social endorsing mechanism. Decis. Support. Syst. 2019, 117, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winata, L.F.A.; Permana, D.; No, J.M.S.; Indonesia, J.B. The effect of electronic coupon value to perceived usefulness and perceived ease-of-use and its implication to behavioral intention to use server-based electronic money. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Chiou-Wei, S.Z.; Inman, J.J. Do shoppers like electronic coupons?: A panel data analysis. J. Retail. 2008, 84, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, S.; Jiang, G. Consumers’ decision-making process in redeeming and sharing behaviors toward app-based mobile coupons in social commerce. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2022, 67, 102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; De Vries, E.L.E.; Ding, A. The mere possession effect of shareable digital coupons: The mediating role of anticipated self-enhancement. J. Consum. Behav. 2023, 22, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, E.; Dong, B.; Zhuang, M.; Cai, F.C. “We Earned the Coupon Together”: The Missing Link of Experience Cocreation in Shared Coupons. J. Mark. 2022, 87, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Yuan, H. Understanding the impact of recipient identification and discount structure on social coupon sharing: The role of altruism and market mavenism. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 2102–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; Yuan, H. Friends with benefits: Social coupons as a strategy to enhance customers’ social empowerment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2018, 46, 768–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Viswanathan, S.; Huang, N.; Zheleva, E. Designing Promotional Incentives to Embrace Social Sharing: Evidence from Field and Online Experiments. Forthcom. MIS Q. 2020, 45, 789–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E. Exploring the effect of coupon proneness and redemption efforts on mobile coupon redemption intentions. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2016, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jia, H.; Yang, S.; Lu, X.; Park, C.W. Do consumers always spend more when coupon face value is larger? The inverted U-shaped effect of coupon face value on consumer spending level. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, F.; Lim, A. Digital coupon promotion and platform selection in the presence of delivery effort. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiden, N.; Chaouali, W.; Baccouche, M. Consumers’ attitude and adoption of location-based coupons: The case of the retail fast food sector. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, J.; Foroudi, P.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Does online retail coupons and memberships create favourable psychological disposition? J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cai, F.; Shi, Z. Do Promotions Make Consumers More Generous? The Impact of Price Promotions on Consumers’ Donation Behavior. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, K.G.; Hyun, S.Y.J. Smart shoppers’ purchasing experiences: Functions of product type, gender, and generation. Int. J. Mark. Stu. 2016, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. It is a match: The impact of congruence between celebrity image and consumer ideal self on endorsement effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 29, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.J.; Koo, D.M. Volunteering as a mechanism to reduce guilt over purchasing luxury items. J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2015, 24, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Teng, L.; Foti, L.; Yuan, Y. Using self-congruence theory to explain the interaction effects of brand type and celebrity type on consumer attitude formation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 301–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J. The malleable self: The role of self-expression in persuasion. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Johar, J.S.; Tidwell, J. Effect of self-congruity with sponsorship on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, T.R.; Roy, D.; Saxena, G. Brand sponsorship effectiveness: How self-congruity, event attachment, and subjective event knowledge matters to sponsor brands. J. Brand. Manag. 2023, 30, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimul, A.S.; Phau, I. Luxury Brand Attachment: Predictors, Moderators and Consequences. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 2466–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, N. Effects of multidimensional destination brand authenticity on destination brand well-being: The mediating role of self-congruence. In Current Issues in Tourism; Taylor Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Aw, C.X.; Chuah, H.W.; Sabri, M.F.; Basha, N.K. Go loud or go home? how power distance belief influences the effect of brand prominence on luxury goods purchase intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Kang, S.K.; Bodenhausen, G.V. Personalized persuasion: Tailoring persuasive appeals to recipients’ personality traits. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternadori, M.; Abitbol, A. How Male Consumers Respond to “Enlightened Manvertising” Campaigns: Gender Schema, Hostile Sexism, And Political Orientation Feed Attitudes. J. Advert. Res. 2022, 62, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastman, J.K.; Iyer, R.; Dekhili, S. Can luxury attitudes impact sustainability? the role of desire for unique products, culture, and brand self-congruence. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 38, 1881–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Martin, D. Self-image congruence in consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Mu, Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, Y. Passionately attached or properly matched? The effect of self-congruence on grocery store loyalty. Brit. Food. J. 2022, 124, 4054–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.; Stephen, J.A. Sex, gender identity, gender role attitudes, and consumer behavior. Psychol. Mark. 1994, 11, 163–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, D.G.; Pauletti, R.E. Gender and adolescent development. J. Res. Adolesc. 2021, 21, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.D.; Menon, M.; Menon, M.; Spatta, B.C.; Hodges, E.; Perry, D.G. The intrapsychics of gender: A model of self-socialization. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 601–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Peng, J.; Guo, X.; Vogel, D. Product Involvement and Routine Use of a Niche Product from a Well-Known Company: The Moderating Effect of Gender. Inform. Manag. 2023, 60, 103758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.M.; Gong, T.; Hughes, C.; Broadbridge, A. Linking leader and gender identities to authentic leadership in small businesses. Gend. Manag. 2017, 32, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantieghem, W.; Vermeersch, H.; Houtte, M.V. Why “gender” disappeared from the gender gap: (re-)introducing gender identity theory to educational gender gap research. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 17, 357–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitelny, H.; Dror, T.; Altman, S.; Bar-Anan, Y. The Relation Between Gender Identity and Well-Being. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 48, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, A.R.; Wilkie, J.E.B.; Jingjing, M.; Isaac, M.S.; Gal, D. Is eco-friendly unmanly? the green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.-J.; Kang, J. How gender moderates the mediating mechanism across social experience, self-referent beliefs and social entrepreneurship intentions. Gend. Manag. 2022, 37, 1045–1063. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Bai, X. Online consumer behaviour and its relationship to website atmospheric induced flow: Insights into online travel agencies in China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chu, H.; Huang, Q.; Chen, X. Enhancing the flow experience of consumers in China through interpersonal interaction in social commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganari, E.; Siomkos, G.J.; Rigopoulou, I.; Vrechopoulos, A.P. Virtual store layout effects on consumer behaviour: Applying an environmental psychology approach in the online travel industry. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 326–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigne, E.; Chatzipanagiotou, K.; Ruiz, C. Pictorial content, sequence of conflicting online reviews and consumer decision-making: The stimulus-organism-response model revisited. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Lee, C.K.; Jung, T. Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. J. Travel. Res. 2020, 59, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Islam, J.; Rahman, Z. The impact of online brand community characteristics on customer engagement: An application of stimulus-organism-response paradigm. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoom, P.T.; Narteh, B.; Odoom, R. Consumer acceptance of online display advertising—The effects of ad characteristics and attitude toward online advertising. Int. J. Internet Mark. Advert. 2022, 16, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, D.L.; Phillips, J. Product gender perceptions and antecedents of product gender congruence. J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Qi, S.; Sengupta, J. Will using a pink product make males become risk averse? The effect of taking a user’s perspective on self-evaluation. In NA—Advances in Consumer Research; Bagchi, R., Block, L., Lee, L., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 2019; Volume 47, p. 847. [Google Scholar]

- Pribilsky, J. Consumption dilemmas: Tracking masculinity, money and transnational fatherhood between the Ecuadorian Andes and New York City. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2012, 38, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Vijaygopal, R. Consumer attitudes towards electric vehicles: Effects of product user stereotype and self-image congruence. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 499–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Argo, J.J. Social identity threat and consumer preferences. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michniewicz, K.S.; Bosson, J.K.; Lenes, J.G.; Chen, J.I. Gender-atypical mental illness as male gender threat. Am. J. Mens. Health 2016, 10, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosson, J.K.; Michniewicz, K.S. Gender dichotomization at the level of ingroup identity: What it is, and why men use it more than women. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 105, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, V.L.; Saenger, C.; Bock, D.E. Do you want to talk about it? When word of mouth alleviates the psychological discomfort of self-threat. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal, D.; Wilkie, J. Real men don’t eat quiche: Regulation of gender-expressive choices by men. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2010, 1, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommer, S.L.; Swaminathan, V. Explaining the endowment effect through ownership: The role of identity, gender, and self-threat. J. Consum. Res. 2013, 39, 1034–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.B.; Thompson, C.J. Man-of-action heroes: The pursuit of heroic masculinity in everyday consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielmann, N.; Dobscha, S.; Lowrey, T.M. Real men don’t buy “mrs. clean”: Gender bias in gendered brands. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2020, 6, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Vohs, K.D.; Funder, D.C. Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behavior? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 2, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbring, T.; Elbæk, C.T.; Lu, C. Masculine (low) digit ratios predict masculine food choices in hungry consumers. Food. Qual. Prefer. 2021, 90, 104168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbring, T.; Sundie, J.; Li, Y.J.; Hill, S. Evolutionary psychological consumer research: Bold, bright, but better with behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 120, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, G. Addressing the sins of consumer psychology via the evolutionary lens. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Dahl, D.W. To be or not be? The influence of dissociative reference groups on consumer preferences. J. Consum. Psychol. 2006, 16, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Huang, Z.T. Social-Jetlagged Consumers and Decreased Conspicuous Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 2022, 49, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazli-Salehi, R.; Torres, I.M.; Madadi, R.; Zúñiga, M.Á. Conspicuous consumption: Impact of narcissism and need for uniqueness on self-brand and communal-brand connection with public vs private use brands. J. Consum. Mark. 2021, 38, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Sundie, J.M.; Cialdini, R.B.; Miller, G.F.; Kenrick, D.T. Blatant benevolence and conspicuous consumption: When romantic motives elicit strategic costly signals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Van den Bergh, B. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterbring, T.; Ringler, C.; Sirianni, N.J.; Gustafsson, A. The Abercrombie & Fitch effect: The impact of physical dominance on male customers’ status-signaling consumption. J. Mark. Res. 2018, 55, 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, R.M.; Borders, L.D. Twenty five years after the Bem Sex-Role Inventory: A reassessment and new issues regarding classification variability. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2001, 34, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalwani, A.K.; Wang, J.J. How do consumers’ cultural backgrounds and values influence their coupon proneness? A multimethod investigation. J. Consum. Res. 2019, 45, 1037–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michniewicz, K.S.; Vandello, J.A.; Bosson, J.K. Men’s (mis) perceptions of the gender threatening consequences of unemployment. Sex. Roles. 2014, 70, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Fishbach, A.; Hsee, C.K. The motivating-uncertainty effect: Uncertainty increases resource investment in the process of reward pursuit. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 41, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aspara, J.; Van Den Bergh, B. Naturally designed for masculinity vs. femininity? Prenatal testosterone predicts male consumers’ choices of gender-imaged products. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2014, 31, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B. Exploring gender differences in online shopping attitude. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Arnulf, J.K.; Iao, L.; Wan, P.; Dai, H. Like or want? Gender differences in attitudes toward online shopping in China. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, S.; Harris, M.A. Gender and e-commerce: An exploratory study. J. Advert. Res. 2003, 43, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neale, L.; Robbie, R.; Martin, B. Gender identity and brand incongruence: When in doubt, pursue masculinity. J. Strateg. Mark. 2016, 24, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.K.; Garrow, J. Gender, identity and the consumption of advertising. Qual. Mark. Res. 2003, 6, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −1.016 *** | −0.815 *** | |

| (0.040) | (0.097) | ||

| Public | 0.024 | 0.129 | −0.215 * |

| (0.064) | (0.078) | (0.096) | |

| Log (Face value) | 0.019 | 0.020 | 0.066 * |

| (0.021) | (0.021) | (0.030) | |

| Gender * Public | −0.244 * | ||

| (0.106) | |||

| Day of the week | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Constant | 1.154 *** | 1.067 *** | 0.155 |

| (0.091) | (0.098) | (0.134) | |

| Observations | 13,169 | 13,169 | 4,770 |

| Log Likelihood | −7441.009 | −7438.379 | −3234.871 |

| Akaike Inf. Crit. | 14,902.020 | 14,898.760 | 6487.742 |

| Hypothesis | Hypothetical Content | Study/Method | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | When facing e-coupon promotions, males are less likely than females to show e-coupon-using intentions. | Study 1; Real-data analysis | Supported |

| H2 | E-coupon users are more likely to be regarded as feminine than those who do not use e-coupons. | Study 2; Experiment | Supported |

| H3 | Gender identity threat mediates the effect of gender on e-coupon-using intention. | Study 3; Online survey | Supported |

| H4 | Affirmation of masculine identity moderates the effect of gender on e-coupon-using intention. When masculine identity is affirmed, men are more likely to show increased e-coupon-using intention, whereas for women, there is no significant difference. | Study 4; Experiment | Supported |

| H5 | The association between e-coupons and femininity moderates the effect of gender on e-coupon-using intention. When the association between e-coupons and femininity is weakened, men are more likely to show increased e-coupon-using intention, whereas for women, there is no significant difference. | Study 5; Experiment | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, C.; Hu, L.; Lei, X.; Yang, D. Do Electronic Coupon-Using Behaviors Make Men Womanish? The Effect of the Coupon–Feminine Stereotype. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 18, 1637-1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030083

Gu C, Hu L, Lei X, Yang D. Do Electronic Coupon-Using Behaviors Make Men Womanish? The Effect of the Coupon–Feminine Stereotype. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2023; 18(3):1637-1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030083

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Chenyan, Liang Hu, Xi Lei, and Defeng Yang. 2023. "Do Electronic Coupon-Using Behaviors Make Men Womanish? The Effect of the Coupon–Feminine Stereotype" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 18, no. 3: 1637-1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030083

APA StyleGu, C., Hu, L., Lei, X., & Yang, D. (2023). Do Electronic Coupon-Using Behaviors Make Men Womanish? The Effect of the Coupon–Feminine Stereotype. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 18(3), 1637-1659. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer18030083