Can I Trust My Phone to Replace My Wallet? The Determinants of E-Wallet Adoption in North Cyprus

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the factors influencing customer intentions to adopt the e-wallet in general?

- (2)

- How does the knowledge that there will be guaranteed reimbursement in case of fraud/unauthorized use influence consumer adoption intentions?

- (3)

- How does the time frame of the guaranteed reimbursement in case of unauthorized use influence consumer adoption intentions?

2. Literature Review

2.1. E-Wallet

2.2. Technology Acceptance Model

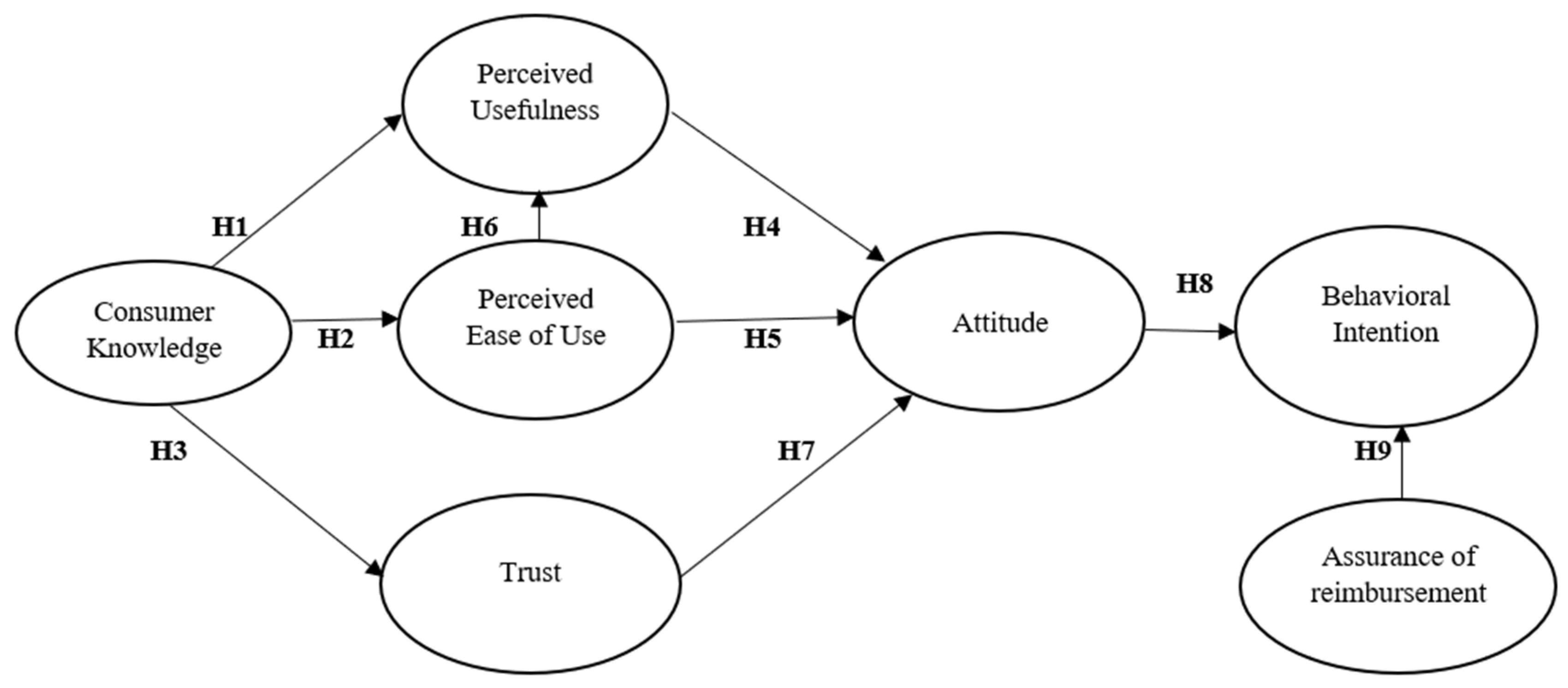

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. Role of Consumer Knowledge (CK)

3.2. Perceived Usefulness (PU)

3.3. Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)

3.4. Trust (TRU)

3.5. Attitude to Use E-Wallet (ATT)

3.6. Behavioral Intention to Use E-Wallet (BI)

3.7. Reimbursement Condition

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample

4.2. Measures

| No | Adopted Indicators | Original Sentence | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I know that to use the e-wallet is a good way to complete transactions | I know the technological advantages of EVs over gasoline vehicles | Huang et al. [29] (2021) |

| 2 | I know how to use e-wallet applications | I know the integration of EVs and ICT to enhance assisted driving | |

| 3 | I know that using the e-wallet is a faster route to complete transactions | I know the technological performance (such as charging time, acceleration, driving comfort and driving range) of EVs | |

| 4 | Using e-wallet services saves my time | Electronic mail enables me to accomplish tasks more quickly | Davis [12] (1989), Triverdi [4] (2016) |

| 5 | The e-wallet has improved quality of my job performance | Using electronic mail improves my job performance | |

| 6 | Using the e-wallet helps me buy easily | Using electronic mail makes it easier to do my job | |

| 7 | E-wallet services have improved my productivity | Using electronic mail increases my productivity | |

| 8 | E-wallet services increase my effectiveness | Using electronic mail enhances my effectiveness on the job | |

| 9 | Interaction with the e-wallet is clear and understandable | My interaction with the system is clear and understandable | Davis [12] (1989), Venkatesh and Bala [19] (2008) |

| 10 | Interaction with the e-wallet does not require mental effort | Interaction with the system does not require a lot of my mental effort | |

| 11 | I think it is easy to get the e-wallet to do what I want to do | I find it easy to get the system do what I want it to do | |

| 12 | In general, the e-wallet is easy to use | I find the system to be easy to use | |

| 13 | The probability of misuse of transaction information in e-wallets is very low | It protects information about my web-shopping behaviour | Parasuraman, Zeithaml & Malhotra [66] (2005) |

| 14 | The probability of misuse of personal information in e-wallest is very low | It does not share my personal information with other sites. | |

| 15 | I am worried about connecting my bank/credit card to the e-wallet application | This site protects information about my credit card | |

| 16 | I feel safe while using e-wallet | This site compensates me for problems it creates | |

| 17 | I like to use the e-wallet | I like to use internet banking | Shih and Fang [67] (2004) |

| 18 | I think using the e-wallet is interesting | Using internet banking is an exciting idea | Nor and Pearson [70] (2008) |

| 19 | It is desirable for me to learn to use the e-wallet | Using internet banking is an appealing idea | |

| 20 | I am willing to keep using the digital wallet in the future | I intend to use internet banking in the future | Taylor and Todd [68] (1995), Lin, Shih, and Sher [69] (2007), Nor and Pearson [70] (2008) |

| 21 | I intend to use a digital wallet on a daily basis | Given the chance, I predict I will use internet banking in the future. | |

| 22 | I plan to keep using the digital wallet regularly | It is likely that I will use internet banking in the future. |

5. Results

5.1. Data Analysis and Results

5.2. Measurement Model

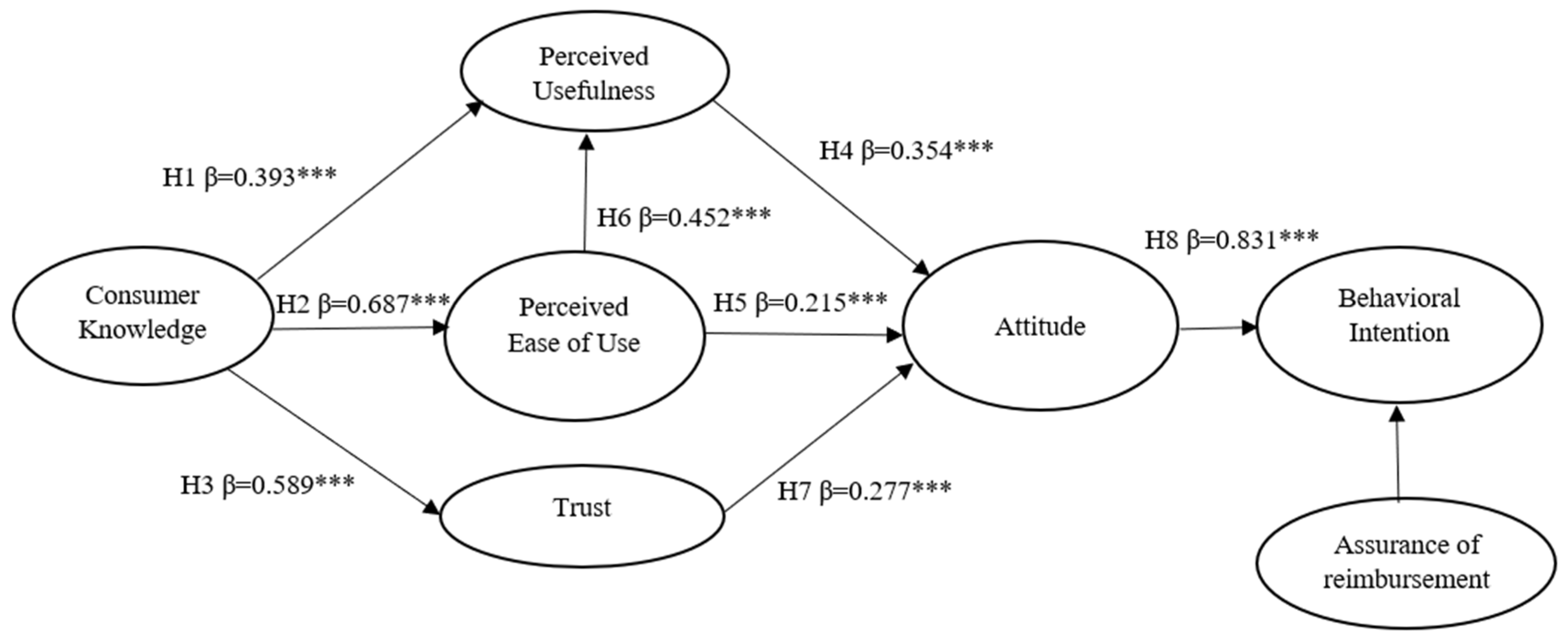

5.3. The Summary of the Relationships

5.4. Results of the Survey Experiment

6. Discussion

7. Implications and Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Task Force on Digital Financing. People’s Money: Harnessing Digitalization to Finance a Sustainable Future. 2022. Available online: http://www.digitalfinancingtaskforce.org (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Pew Charitable Trusts. Are Americans Embracing Mobile Payments? Issue Brief. 2019. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2019/10/mobilepayments_brief_final.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- De Kerviler, G.; Demoulin, N.T.; Zidda, P. Adoption of in-store mobile payment: Are perceived risk and convenience the only drivers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, J. Factors determining the acceptance of e wallets. Int. J. Appl. Mark. Manag. 2016, 1, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. The moderating effect of experience in the adoption of mobile payment tools in Virtual Social Networks: The m-Payment Acceptance Model in Virtual Social Networks (MPAM-VSN). Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- Taufan, A.; Yuwono, R.T. Analysis of factors that affect intention to use e-wallet through the technology acceptance model approach (case study: GO-PAY). Int. J. Sci. Res. 2019, 8, 413–419. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, S.; Khong, K.W. Examining actual consumer usage of E-wallet: A case study of big data analytics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.L.; Magnier-Watanabe, R. Building a research model for mobile wallet consumer adoption: The case of mobile Suica in Japan. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 7, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hahn, C.; Sutrave, K. Mobile payment security, threats, and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2016 Second International Conference on Mobile and Secure Services (MobiSecServ), Gainesville, FL, USA, 26–27 February 2016; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Kozar, K.A.; Larsen, K.R. The technology acceptance model: Past, present, and future. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2003, 12, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Charness, N.; Boot, W.R. Technology, gaming, and social networking. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangunić, N.; Granić, A. Technology acceptance model: A literature review from 1986 to 2013. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2015, 14, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. User acceptance of computer technology, A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, J.H. Development, extension, and application: A review of the technology acceptance model. Inf. Syst. Educ. J. 2006, 5, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Somali, S.A.; Gholami, R.; Clegg, B. An investigation into the acceptance of online banking in Saudi Arabia. Technovation 2009, 29, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijnen, M.; Wetzels, M.; de Ruyter, K. Consumer acceptance of wireless finance. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2004, 8, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luarn, P.; Lin, H.H. Toward an understanding of the behavioral intention to use mobile banking. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2005, 21, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nysveen, H.; Pedersen, P.E.; Thorbjørnsen, H. Intentions to use mobile services: Antecedents and cross-service comparisons. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 330–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikkarainen, T.; Pikkarainen, K.; Karjaluoto, H.; Pahnila, S. Consumer acceptance of online banking: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Xinyan, Z.; Yue, M. Notice of Retraction: Literature review on consumer adoption behavior of mobile commerce services. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on E-Business and E-Government (ICEE), Shanghai, China, 6–8 May 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sana’a, Y. A critical review of models and theories in field of individual acceptance of technology. Int. J. Hybrid Inf. Technol. 2016, 9, 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- El-Masri, M.; Tarhini, A. Factors affecting the adoption of e-learning systems in Qatar and USA: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2). Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2017, 65, 743–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spies, R.; Grobbelaar, S.; Botha, A. A scoping review of the application of the task-technology fit theory. In Responsible Design, Implementation and Use of Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 397–408. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakonmäki, R.; Simons, A.; Müller, O.; Brocke, J.V. ECM implementations in practice: Objectives, processes, and technologies. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2018, 31, 704–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lin, Y.; Lim, M.K.; Tseng, M.L.; Zhou, F. The influence of knowledge management on adoption intention of electric vehicles: Perspective on technological knowledge. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2021, 121, 1481–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Hong, Z.S.; Zhu, J.; Yan, J.J.; Qi, J.Q.; Liu, P. Promoting green residential buildings: Residents’ environmental attitude, subjective knowledge, and social trust matter. Energy Policy 2018, 112, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Feick, L. Consumer knowledge assessment. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, K.; Breitner, M.H. Consumer purchase intentions for electric vehicles: Is green more important than price and range? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 51, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig-Lewis, N.; Marquet, M.; Palmer, A.; Zhao, A.L. Enjoyment and social influence: Predicting mobile payment adoption. Serv. Ind. J. 2015, 35, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: System characteristics, user perceptions and behavioral impacts. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1993, 38, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavian, C.; Guinaliu, M.; Lu, Y. Mobile payments adoption–introducing mindfulness to better understand consumer behavior. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 1575–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.H.; Chiu, C.M. Internet self-efficacy and electronic service acceptance. Decis. Support Syst. 2004, 38, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; de Luna, I.R.; Montoro-Rıos, F. Intention to use new mobile payment systems: A comparative analysis of SMS and NFC payments. Econ. Res. 2017, 30, 892–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. Consumer attitude and intention to adopt mobile wallet in India–An empirical study. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1590–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, R.; Dhiman, N.; Kanojia, H. Understanding intentions and actual use of mobile wallets by millennial: An extended TAM model perspective. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, T.; Guo, J.; Ondrus, J. A critical review of mobile payment research. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2015, 14, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Marinkovic, V.; de Luna, I.R.; Kalinic, Z. Predicting the determinants of mobile payment acceptance: A hybrid SEM-neural network approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J. A global approach to the analysis of user behavior in mobile payment systems in the new electronic environment. Serv. Bus. 2018, 12, 25–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matemba, E.D.; Li, G. Consumers’ willingness to adopt and use WeChat wallet: An empirical study in South Africa. Technol. Soc. 2018, 53, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, K.B.; Tan, G.W.H. Mobile technology acceptance model: An investigation using mobile users to explore smartphone credit card. Expert Syst. Appl. 2016, 59, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.T.T.; Ho, J.C. The effects of product-related, personal-related factors and attractiveness of alternatives on consumer adoption of NFC-based mobile payments. Technol. Soc. 2015, 43, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, M.; Jan, M.T. Factors influencing the use of m-commerce: An extended technology acceptance model perspective. International Journal of Economics. Manag. Account. 2018, 26, 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Maroof, R.S.; Al-Emran, M. Students’ acceptance of Google classroom: An exploratory study using PLS-SEM approach. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2018, 13, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Esterik-Plasmeijer, P.W.; van Raaij, W.F. Banking system trust, bank trust, and bank loyalty. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldás-Manzano, J.; Lassala-Navarré, C.; Ruiz-Mafé, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. The role of consumer innovativeness and perceived risk in online banking usage. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2009, 27, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavian, C.; Guinaliu, M.; Torres, E. The influence of corporate image on consumer trust: A comparative analysis in traditional versus internet banking. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D. Reflections on the dimensions of trust and trustworthiness among online consumers. ACM SIGMIS Database DATABASE Adv. Inf. Syst. 2002, 33, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lii, Y.S.; Sy, E. Internet differential pricing: Effects on consumer price perception, emotions, and behavioral responses. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H. Towards an understanding of the consumer acceptance of mobile wallet. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 1343–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.; Graham, S.; Bonacum, D. The human factor: The critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2004, 13 (Suppl. 1), i85–i90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariffin, S.K.; Rahman, M.F.R.A.; Muhammad, A.M.; Zhang, Q. Understanding the consumer’s intention to use the e-wallet services. Span. J. Mark. -ESIC 2021, 25, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apanasevic, T.; Markendahl, J.; Arvidsson, N. Stakeholders’ expectations of mobile payment in retail: Lessons from Sweden. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2016, 34, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luna, I.R.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. Mobile payment is not all the same: The adoption of mobile payment systems depending on the technology applied. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Anong, S.T.; Zhang, L. Understanding the impact of financial incentives on NFC mobile payment adoption: An experimental analysis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 1296–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierz, P.G.; Schilke, O.; Wirtz, B.W. Understanding consumer acceptance of mobile payment services: An empirical analysis. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2010, 9, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulandari, N. Cashless payment in tourism. An application of technology acceptance model. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2017, 8, 1550–1553. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, N.; Upadhyay, S.; Abed, S.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Consumer adoption of mobile payment services during COVID-19: Extending meta-UTAUT with perceived severity and self-efficacy. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2022, 40, 960–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzadeh, J.; Ozturk, A.B.; Bilgihan, A. Security-related factors in extended UTAUT model for NFC based mobile payment in the restaurant industry. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 70, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer On Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Said, H.; Tanova, C. Workplace bullying in the hospitality industry: A hindrance to the employee mindfulness state and a source of emotional exhaustion. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 96, 102961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Malhotra, A. ES-QUAL: A multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality. J. Serv. Res. 2005, 7, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.Y.; Fang, K. The use of a decomposed theory of planned behavior to study Internet banking in Taiwan. Internet Res. 2004, 14, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Shih, H.Y.; Sher, P.J. Integrating technology readiness into technology acceptance: The TRAM models. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nor, K.M.; Pearson, J.M. An exploratory study into the adoption of internet banking in a developing country: Malaysia. J. Internet Commer. 2008, 7, 29–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.; Boudreau, M.C. Structural equation modeling and regression: Guidelines for research practice. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2000, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharafi, M.A.; Al-Qaysi, N.; Iahad, N.A.; Al-Emran, M. Evaluating the sustainable use of mobile payment contactless technologies within and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic using a hybrid SEM-ANN approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 40, 1071–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measures | Items | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 147 | 49.0 | |

| Female | 153 | 51.0 | |

| Age | |||

| 20–40 years | 122 | 40.7 | |

| 40–60 years | 133 | 44.3 | |

| 60–75+ years | 45 | 15,0 | |

| Education Level | |||

| Primary school | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Secondary school | 38 | 12.7 | |

| Associate degree | 24 | 8.0 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 132 | 44.0 | |

| Master’s degree | 104 | 34.6 | |

| Doctorate | |||

| How often do you use your internet bank account? | |||

| I don’t have an internet bank account | 49 | 16.3 | |

| Less than once a week | 37 | 12.3 | |

| Once a week | 61 | 20.3 | |

| Every day | 120 | 40.0 | |

| Several times a day | 33 | 11.0 | |

| Do you shop online? | |||

| Never | 31 | 10.3 | |

| Occasionally | 53 | 17.7 | |

| Sometimes | 97 | 32.3 | |

| Often | 92 | 30.7 | |

| Very often | 27 | 9.0 | |

| Do you make payments online? | |||

| Never | 22 | 7.3 | |

| Rarely | 42 | 14.0 | |

| Sometimes | 73 | 24.3 | |

| Often | 68 | 22.7 | |

| Regularly | 95 | 31.7 | |

| Do you have an e-wallet? If so, how often do you use it? | |||

| Never | 132 | 44.0 | |

| Rarely | 39 | 13.0 | |

| Sometimes | 54 | 18.0 | |

| Often | 46 | 15.3 | |

| Regularly | 29 | 9.7 |

| Constructs | Indicators | Loadings | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s Alpha | VIF | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.867 | 0.686 | 0.770 | 0.545 | ||||

| Consumer Knowledge | CK1: I know that to use the e-wallet is a good way to complete transactions | 0.875 | 1.835 | ||||

| CK2: I know how to use e-wallet applications | 0.796 | 1.512 | |||||

| CK3: I know that using an e-wallet is a faster route to complete transactions | 0.812 | 1.547 | |||||

| 0.915 | 0.682 | 0.884 | 0.691 | ||||

| Perceived Usefulness | PU1: I believe that using e-wallet services will save my time | 0.779 | 2.623 | ||||

| PU2: I think that e-wallet will improve the quality of my job performance | 0.833 | 2.338 | |||||

| PU3: The e-wallet will help me buy easily | 0.843 | 2.848 | |||||

| PU4: E-wallet services will improve my productivity | 0.820 | 2.429 | |||||

| PU5: E-wallet services will increase my effectiveness | 0.853 | ||||||

| 0.904 | 0.702 | 0.859 | 0.584 | ||||

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEOU1: Interaction with e-wallets will be clear and understandable | 0.819 | 1.946 | ||||

| PEOU2: Interaction with e-wallets will not require mental effort. | 0.869 | 1.919 | |||||

| PEOU3: I think it will be easy to get e-wallets to do what I want to do | 0.832 | 2.273 | |||||

| PEOU4: In general, I believe that the e-wallet will be easy to use | 0.831 | 1.902 | |||||

| 0.921 | 0.745 | 0.886 | 0.496 | ||||

| Trust | TRU1: The probability of misuse of transaction information in e-wallets is very low | 0.858 | 3.201 | ||||

| TRU2: The probability of misuse of personal information in e-wallets is very low | 0.902 | 3.924 | |||||

| TRU3: I am worried about connecting my bank/credit card to the e-wallet application | 0.820 | 1.917 | |||||

| TRU4: I will feel safe while using e-wallets | 0.873 | 2.279 | |||||

| 0.908 | 0.766 | 0.848 | 0.347 | ||||

| Attitude | ATT1: I would like to use e-wallet | 0.881 | 2.154 | ||||

| ATT2: I think using e-wallet will be interesting | 0.924 | 2.865 | |||||

| ATT3: It is desirable for me to learn to use the e-wallet | 0.818 | 1.880 | |||||

| 0.951 | 0.866 | 0.923 | |||||

| Behavioral Intention | BI1: I am willing to keep using e-wallets in the future | 0.921 | 3.102 | ||||

| BI2: I intend to use an e-wallets on a daily basis | 0.920 | 3.503 | |||||

| BI3: I plan to keep using e-wallets regularly | 0.951 | 4.699 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attitude | 0.875 | |||||

| 2 | Behavioral intention | 0.831 | 0.931 | ||||

| 3 | Consumer knowledge | 0.650 | 0.649 | 0.828 | |||

| 4 | Perceived ease of use | 0.646 | 0.693 | 0.686 | 0.838 | ||

| 5 | Perceived usefulness | 0.666 | 0.682 | 0.704 | 0.722 | 0.826 | |

| 6 | Trust | 0.614 | 0.680 | 0.589 | 0.634 | 0.566 | 0.864 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attitude | ||||||

| 2 | Behavioral intention | 0.934 | |||||

| 3 | Consumer knowledge | 0.792 | 0.767 | ||||

| 4 | Perceived ease of use | 0.745 | 0.778 | 0.843 | |||

| 5 | Perceived usefulness | 0.758 | 0.751 | 0.842 | 0.819 | ||

| 6 | Trust | 0.686 | 0.746 | 0.709 | 0.720 | 0.635 |

| Hypotheses Relationships | Beta | Significance | Effect Size (f2) | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK -> PU | 0.393 | 0.000 | 0.985 | Supported |

| CK -> PEOU | 0.687 | 0.000 | 0.151 | Supported |

| CK -> TRU | 0.589 | 0.000 | 0.530 | Supported |

| PU -> ATT | 0.354 | 0.000 | 0.126 | Supported |

| PEOU -> PU | 0.452 | 0.000 | 0.271 | Supported |

| PEOU -> ATT | 0.216 | 0.001 | 0.041 | Supported |

| TRU -> ATT | 0.277 | 0.000 | 0.097 | Supported |

| ATT -> BI | 0.831 | 0.000 | 2.233 | Supported |

| Type | Reimbursement Period | Consumer Knowledge | Perceived Usefulness | Perceived Ease of Use | Trust | Attitude | Behavioral Intention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Immediate | 4.1182 | 3.9636 | 3.9977 | 3.6841 | 4.1455 | 4.0303 |

| Group 2 | 5 days | 3.9020 | 3.7608 | 3.9044 | 3.4436 | 3.9444 | 3.7451 |

| Control 3 | No information | 3.9729 | 3.8943 | 3.9375 | 3.5313 | 4.0341 | 3.8333 |

| Group Type | Mean | St. Deviation | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Immediate reimbursement | 4.0303 | 0.73578 | 110 |

| 2 Reimbursement in 5 days | 3.7451 | 0.86387 | 102 |

| 3 No knowledge | 3.8333 | 0.82428 | 88 |

| Total | 3.8756 | 0.81380 | 300 |

| Target Variable | SS | df | MS | F | Sig |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral intention | |||||

| Dependent variable (type) | 1.045 | 2 | 0.523 | 1.345 | 0.262 |

| Covariate (consumer knowledge) | 78.915 | 1 | 78.915 | 202.984 | 0.000 |

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Signif. | Result | Beta | Signif. | Result | Beta | Signif. | Result | |

| CK -> PU | 0.311 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.389 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.504 | 0.000 | Supported |

| CK -> PEOU | 0.658 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.759 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.627 | 0.000 | Supported |

| CK -> TRU | 0.586 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.630 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.546 | 0.000 | Supported |

| PU -> ATT | 0.412 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.243 | 0.099 | Not Supported | 0.403 | 0.000 | Supported |

| PEOU -> PU | 0.565 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.472 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.303 | 0.007 | Supported |

| PEOU -> ATT | 0.250 | 0.037 | Supported | 0.239 | 0.100 | Not supported | 0.160 | 0.131 | Not supported |

| TRU -> ATT | 0.113 | 0.281 | Not supported | 0.381 | 0.004 | Supported | 0.333 | 0.000 | Supported |

| ATT -> BI | 0.766 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.879 | 0.000 | Supported | 0.840 | 0.000 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kınış, F.; Tanova, C. Can I Trust My Phone to Replace My Wallet? The Determinants of E-Wallet Adoption in North Cyprus. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 1696-1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040086

Kınış F, Tanova C. Can I Trust My Phone to Replace My Wallet? The Determinants of E-Wallet Adoption in North Cyprus. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2022; 17(4):1696-1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040086

Chicago/Turabian StyleKınış, Fatma, and Cem Tanova. 2022. "Can I Trust My Phone to Replace My Wallet? The Determinants of E-Wallet Adoption in North Cyprus" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 17, no. 4: 1696-1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040086

APA StyleKınış, F., & Tanova, C. (2022). Can I Trust My Phone to Replace My Wallet? The Determinants of E-Wallet Adoption in North Cyprus. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 17(4), 1696-1715. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040086