The Whole Is More than Its Parts: A Multidimensional Construct of Values in Consumer Information Search Behavior on SNS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

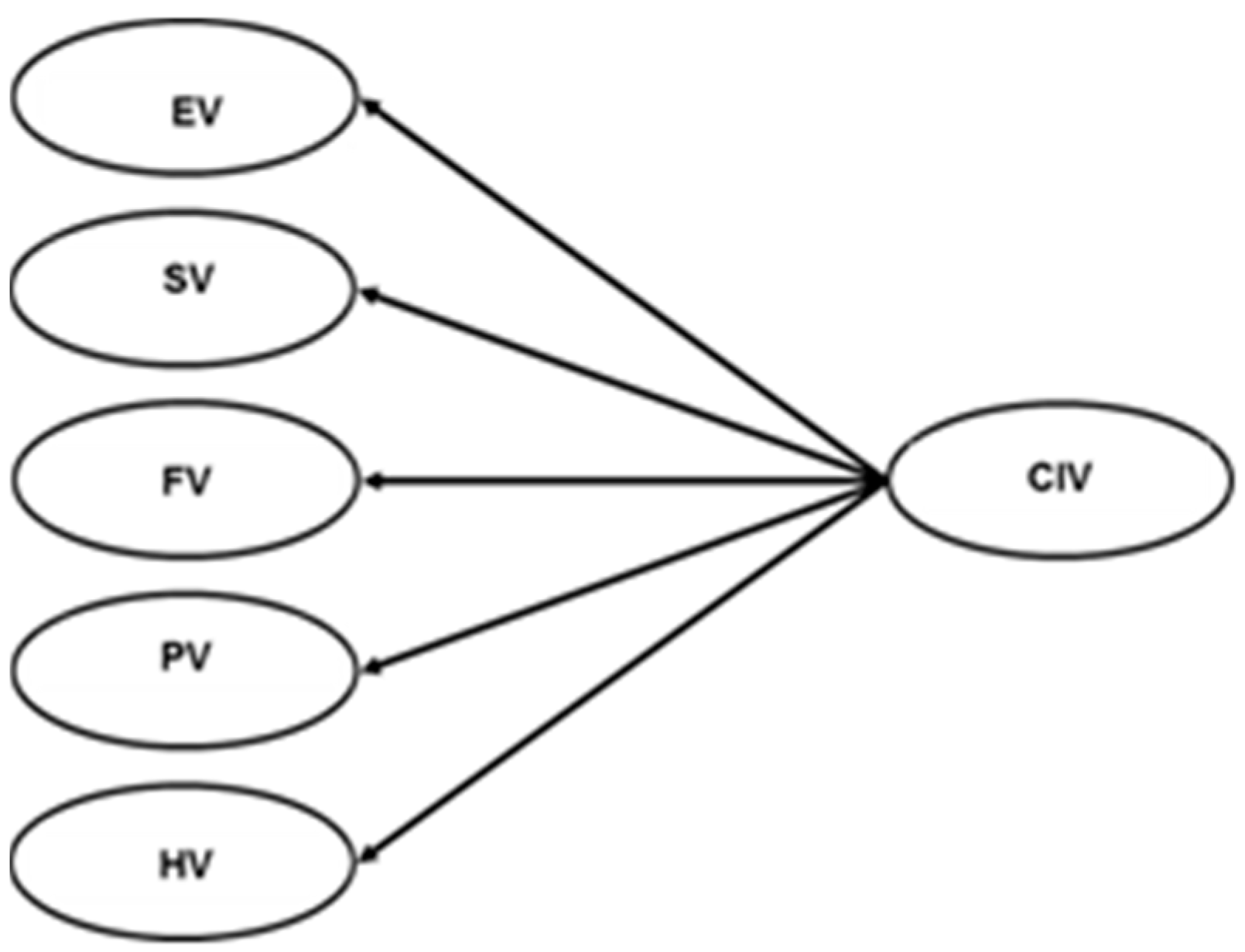

2.1. Distinct Facets of the CIV

2.2. CIV and Its Explanatory Power

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measurement

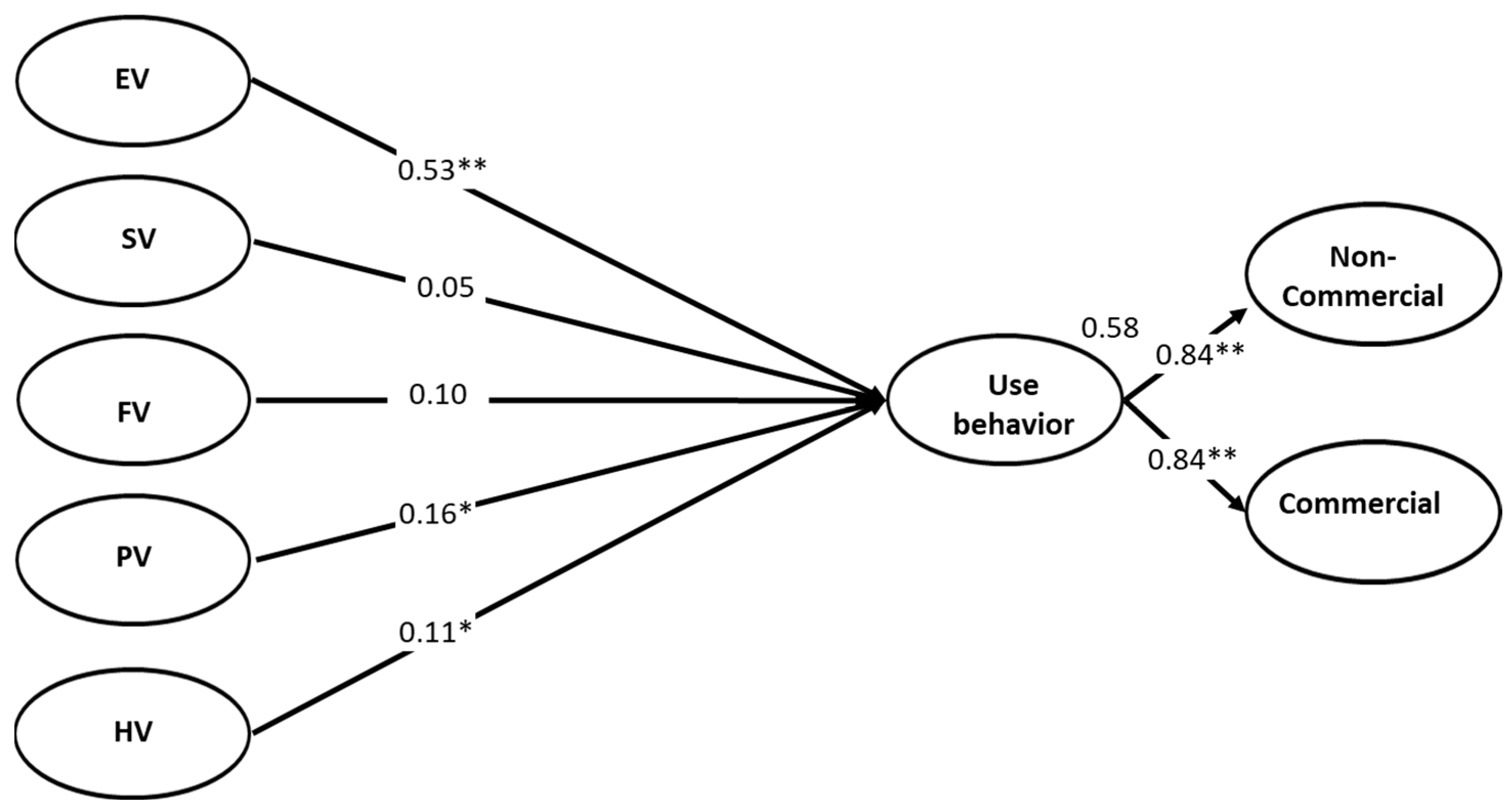

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beatty, S.E.; Smith, S.M. External Search Effort: An Investigation Across Several Product Categories. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, N.; Ratchford, B.T. An Empirical Test of a Model of External Search for Automobiles. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.; Gvili, Y.; Hino, H. Engagement of Ethnic-Minority Consumers with Electronic Word of Mouth (EWOM) on Social Media: The Pivotal Role of Intercultural Factors. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2608–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridasan, A.C.; Fernando, A.G.; Saju, B. A Systematic Review of Consumer Information Search in Online and Offline Environments. RAUSP Manag. J. 2021, 56, 234–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.F.; Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W. Consumer Behavior, 8th ed.; Dryden: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kol, O.; Nebenzahl, I.D.; Lev-On, A.; Levy, S. SNS Adoption for Consumer Active Information Search (AIS)—The Dyadic Role of Information Credibility. Int. J. Human–Computer Interact. 2021, 37, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, A.; Matthews, L. The Use of Facebook for Information Seeking, Decision Support, and Self-Organization Following a Significant Disaster. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 1680–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Wang, W. The Influence of Perceived Value on Purchase Intention in Social Commerce Context. Internet Res. 2017, 27, 772–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. They Say They Want, a Revolution: Total Retail Report; PwC: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kol, O.; Levy, S.; Nebenzahl, I.D. Consumer Values as Mediators in Social Network Information Search. In Advances in Advertising Research; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; Volume VII, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Sharma, K.; Pappas, I.O.; Giannakos, M. Seeking Information on Social Commerce: An Examination of the Impact of User- and Marketer-Generated Content Through an Eye-Tracking Study. Inf. Syst. Front. 2021, 23, 1273–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvili, Y.; Kol, O.; Levy, S. The Value(s) of Information on Social Network Sites: The Role of User Personality Traits. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 2020, 70, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. How Should Multifaceted Personality Constructs Be Tested? Issues Illustrated by Self-Monitoring, Attributional Style, and Hardiness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vij, A.; Walker, J.L. How, When and Why Integrated Choice and Latent Variable Models Are Latently Useful. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2016, 90, 192–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, N.A.; Leonidou, L.C.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing Performance Outcomes in Marketing. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Benyoucef, M. Consumer Behavior in Social Commerce: Results from a Meta-Analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 167, 120734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daiya, A.; Roy, S. User and Firm Generated Content on Online Social Media. Int. J. Online Mark. 2016, 6, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsman, A.; Mudd, G.; Rich, M.; Bruich, S. The Power of “Like”. J. Advert. Res. 2012, 52, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackshaw, P.; Nazzaro, M. Consumer-Generated Media (CGM) 101: Word-of Mouth in the Age of the Web-Fortified Consumer; BuzzMetrics: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. An Empirical Investigation of Information Sharing Behavior on Social Commerce Sites. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 686–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvili, Y.; Levy, S. Consumer Engagement in Sharing Brand-Related Information on Social Commerce: The Roles of Culture and Experience. J. Mark. Commun. 2021, 27, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Chiu, P.-Y.; Lee, M.K.O. Online Social Networks: Why Do Students Use Facebook? Comput. Human Behav. 2011, 27, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducoffe, R.H. How Consumers Assess the Value of Advertising. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 1995, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvili, Y.; Levy, S. Antecedents of Attitudes toward EWOM Communication: Differences across Channels. Internet Res. 2016, 26, 1030–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption Values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrikulu, C. Theory of Consumption Values in Consumer Behaviour Research: A Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 1176–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer Perceived Value: The Development of a Multiple Item Scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.H.; Chang, H.H.; Yeh, C.H. The Effects of Consumption Values and Relational Benefits on Smartphone Brand Switching Behavior. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler, G.J. The Economics of Information. J. Polit. Econ. 1961, 69, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P. Advertising as Information. J. Polit. Econ. 1974, 82, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, K.G.; Hyun, S.-Y.J. Smart Shoppers’ Purchasing Experiences: Functions of Product Type, Gender, and Generation. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2016, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Shen, X.L. Consumers’ Decisions in Social Commerce Context: An Empirical Investigation. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 79, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampe, C.; Vitak, J.; Gray, R.; Ellison, N.B. Perceptions of Facebook’s Value as an Information Source. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 3195–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimand-Sheiner, D.; Kol, O.; Levy, S. Help Me If You Can: The Advantage of Farmers’ Altruistic Message Appeal in Generating Engagement with Social Media Posts during COVID-19. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shia, A.S.; Chang, K.-F.; Huang, Y.-H. Social Marketing of Electronic Coupons Under the Perspective of Social Sharing Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.B.; Li, Y.N.; Wu, B.; Li, D.J. How WeChat Can Retain Users: Roles of Network Externalities, Social Interaction Ties, and Perceived Values in Building Continuance Intention. Comput. Human Behav. 2017, 69, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, K.; Gordon, R.; Roggeveen, K.; Waitt, G.; Cooper, P. Social Marketing and Value in Behaviour?: Perceived Value of Using Energy Efficiently among Low Income Older Citizens. J. Soc. Mark. 2016, 6, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Song, S.; House, D.; Kwon, M. Role of Gender Differences on Individuals’ Responses to Electronic Word-of-Mouth in Social Interactions. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 3001–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Lu, Y.; Wei, K.K.; Zhang, J. Understanding Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty: An Empirical Study of Mobile Instant Messages in China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Gao, J.; Yang, J. Social Value and Content Value in Social Media: Two Ways to Flow. J. Adv. Manag. Sci. 2015, 3, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Lee, G.; Hur, K.; Kim, T.T. Online Travel Information Value and Its Influence on the Continuance Usage Intention of Social Media. Serv. Bus. 2018, 12, 85–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Naylor, G.; Sivadas, E.; Sugumaran, V. The Unrealized Value of Incentivized EWOM Recommendations. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljukhadar, M.; Bériault Poirier, A.; Senecal, S. Imagery Makes Social Media Captivating! Aesthetic Value in a Consumer-as-Value-Maximizer Framework. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2020, 14, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. The Millennial Consumer in the Texts of Our Times: Experience and Entertainment. J. Macromarketing 2000, 20, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facebook Audience Insights. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/ads/audience-insights/people?act=125680540&age=18-&country=US (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson Upper Saddle River: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.M.K.; Lee, M.K.O. What Drives Consumers to Spread Electronic Word of Mouth in Online Consumer-Opinion Platforms. Decis. Support Syst. 2012, 53, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvili, Y.; Levy, S. Consumer Engagement with EWOM on Social Media: The Role of Social Capital. Online Inf. Rev. 2018, 42, 482–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct Variables and Items | Std. Coef. | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Value (EV) | 0.72 | 0.91 | 0.92 | |

| The information on products/services I receive on Facebook helps me save money. | 0.79 ** | |||

| The information on products/services I receive on Facebook helps me get greater value for the money I pay. | 0.86 ** | |||

| The information on products/services I receive on Facebook reduces my search time on Facebook. | 0.84 ** | |||

| The information on products/services I receive on Facebook helps me find better offers and solutions. | 0.89 ** | |||

| Social Value (SV) | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.91 | |

| The information on products/services, I search for on Facebook lets me make a good impression on other people. | 0.87 ** | |||

| The information on products/services, I search for on Facebook gives me a sense of belonging to a group or to other people. | 0.91 ** | |||

| The information on products/services, I search for on Facebook helps me to feel accepted by other people. | 0.81 ** | |||

| The information on products/services, I search for on Facebook improves the way I am perceived by others and tells people who I am. | 0.75 ** | |||

| Functional Value (FV) | 0.66 | 0.90 | 0.93 | |

| I trust the information I get on Facebook about products/services. | 0.77 ** | |||

| The information on products/services that I receive on Facebook is usually reliable. | 0.80 ** | |||

| Information about products/services I receive on Facebook is generally credible. | 0.75 ** | |||

| The information I receive on Facebook allows me to get products/services in accordance with my needs | 0.88 ** | |||

| I get quality information about products/services on Facebook. | 0.87 ** | |||

| Psychological Value (PV) | 0.63 | 0.89 | 0.91 | |

| The information I receive on Facebook makes it easy for me to try new products and services. | 0.82 ** | |||

| The information I receive on Facebook reduces the concerns I have when making a purchase decision. | 0.81 ** | |||

| The information I receive on Facebook allows me to make purchase decisions in accordance with societal expectations or what is acceptable. | 0.71 ** | |||

| The information I receive on Facebook reduces the concerns I have when using the products or services. | 0.80 ** | |||

| The information I receive on Facebook helps me decide what is best for me. | 0.81 ** | |||

| Hedonic Value (HV) | 0.80 | 0.92 | 0.92 | |

| Searching for information about products/services on Facebook is fun for me | 0.94 ** | |||

| I enjoy searching for information about products/services on Facebook | 0.98 ** | |||

| Finding information about products/services on Facebook is entertaining and amusing | 0.75 ** | |||

| Non-Commercial Channels (Personal Profile &Groups of Interest) | 0.52 | 0.86 | 0.85 | |

| I post a question in my personal profile requesting a recommendation or an opinion about a product from family/friends. | 0.74 ** | |||

| I request a certain person opinion about a product in a private message on Facebook’s Messenger. | 0.72 ** | |||

| I read reviews and recommendation written in the past by friends/family on my personal profile | 0.68 ** | |||

| I post a question on a relevant Facebook group (e.g., cooking moms, defective dads, etc.) in order to receive a recommendation or an opinion about a product. | 0.77 ** | |||

| I read opinions and recommendation about a product that were written in the past by the participants in a relevant Facebook group (e.g., cooking moms, defective dads, etc.) | 0.74 ** | |||

| I “like” or write a response about information on a product that interests me in a relevant Facebook group | 0.66 ** | |||

| Commercial Channels (Brand Page & Advertisement) | 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.86 | |

| I go to a brand page to get information about a product or request the information by sending a message on the brand page Facebook messenger. | 0.72 ** | |||

| I go to a brand page to find coupons or promotions or marketing offers. | 0.77 ** | |||

| I am interested in coupons and marketing offers I get on my personal profile from brand pages I “liked. | 0.67 ** | |||

| I read relevant ads that appear on my profile. | 0.79 ** | |||

| I actively “like” relevant ads that appear on my profile. | 0.70 ** | |||

| If it is relevant to me, I click on the ad to get more information about the product. | 0.60 ** |

| NonComm | Comm | EV | SV | FV | PV | HV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NonComm. | 0.52 | 0.60 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.45 ** |

| Comm. | 0.36 | 0.51 | 0.60** | 0.39 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.44 ** |

| EV | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.72 | 0.49 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.70 ** | 0.51 ** |

| SV | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.7 | 0.41 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.41 ** |

| FV | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.17 | 0.66 | 0.68 ** | 0.50 ** |

| PV | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.63 | 0.51 ** |

| HV | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.8 |

| Construct Variables and Items | Std. Coef. | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIV | 0.67 | 0.91 | |

| FV | 0.83 ** | ||

| PV | 0.93 ** | ||

| EV | 0.89 ** | ||

| SV | 0.64 ** | ||

| HV | 0.65 ** | ||

| Use Behavior—Channel | 0.76 | 0.86 | |

| Non-Commercial | 0.87 ** | ||

| Commercial | 0.87 ** |

| EV | SV | FV | PV | HV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use Behavior | 0.672 ** | 0.436 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.596 ** | 0.497 ** |

| Relationship | Standardized Effect | Regression Weights | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | Total-Direct | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | |

| Model 1—Separately | 0.58 | |||||

| EV → Use Behavior | 0.532 | 0.383 | 0.056 | 60.810 | <0.01 | |

| SV → Use Behavior | 0.048 | 0.370 | 0.40 | 0.909 | 0.364 | |

| FV → Use Behavior | 0.098 | 0.840 | 0.52 | 10.610 | 0.107 | |

| PV → Use Behavior | 0.155 | 0.115 | 0.58 | 20.001 | <0.05 | |

| HV → Use Behavior | 0.112 | 0.800 | 0.33 | 20.408 | <0.05 | |

| Model 2—CIV | 0.69 | |||||

| CIV → Use Behavior | 0.832 | 0.939 | 0.77 | 120.208 | <0.01 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kol, O.; Levy, S. The Whole Is More than Its Parts: A Multidimensional Construct of Values in Consumer Information Search Behavior on SNS. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 1685-1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040085

Kol O, Levy S. The Whole Is More than Its Parts: A Multidimensional Construct of Values in Consumer Information Search Behavior on SNS. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2022; 17(4):1685-1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040085

Chicago/Turabian StyleKol, Ofrit, and Shalom Levy. 2022. "The Whole Is More than Its Parts: A Multidimensional Construct of Values in Consumer Information Search Behavior on SNS" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 17, no. 4: 1685-1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040085

APA StyleKol, O., & Levy, S. (2022). The Whole Is More than Its Parts: A Multidimensional Construct of Values in Consumer Information Search Behavior on SNS. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 17(4), 1685-1695. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17040085