Are the Time-Poor Willing to Pay More for Online Grocery Services? When ‘No’ Means ‘Yes’

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Online Grocery Services: Theoretical Background

2.1. The Logistics

2.2. How Convenient Is E-Grocery Shopping?

2.3. Willingness to Pay for E-Grocery Services

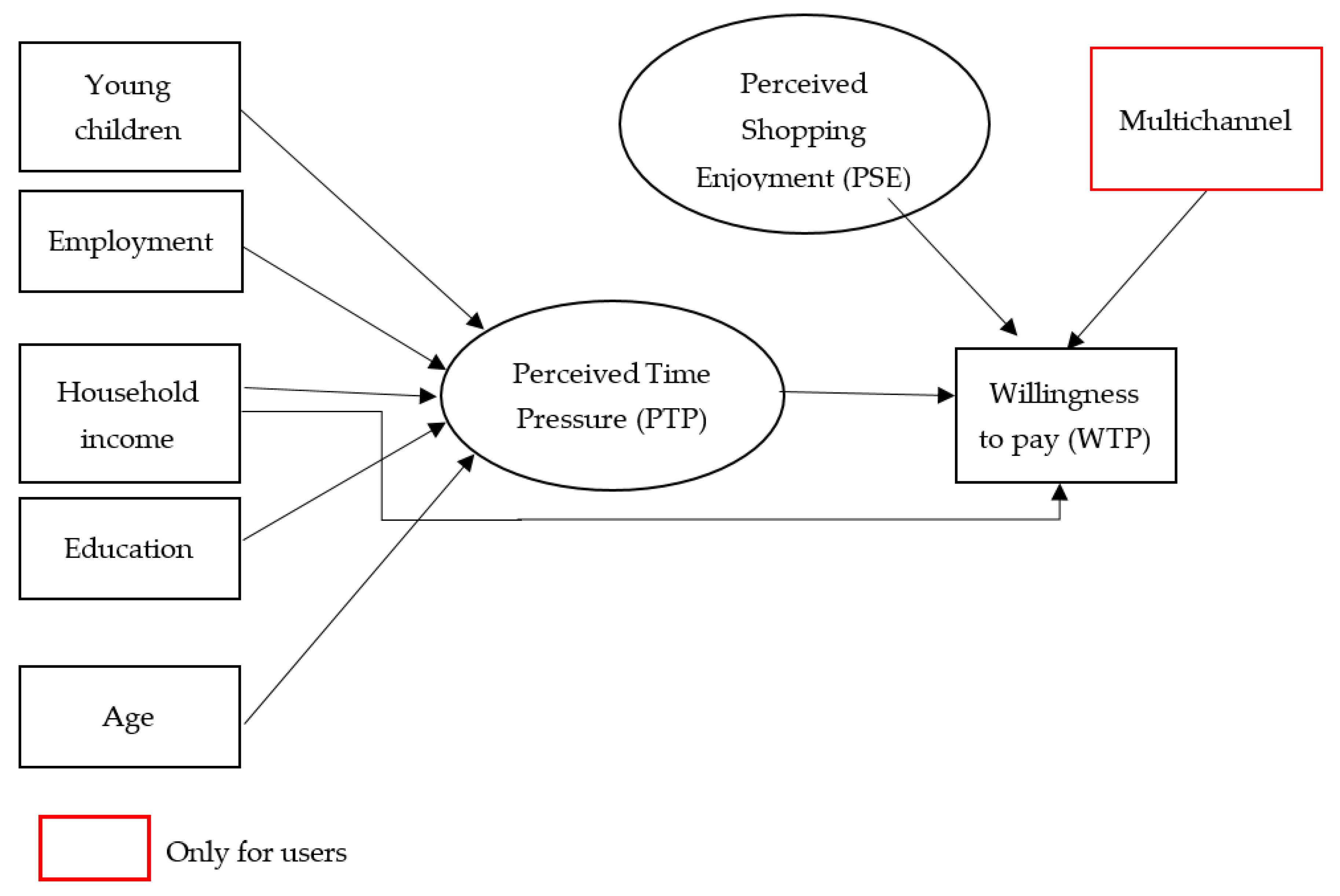

3. Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

4. Methodology

4.1. Sampling Strategy and Data Collection

4.2. Operationalization of the Variables

5. Descriptive Results

5.1. Composition of the Sample

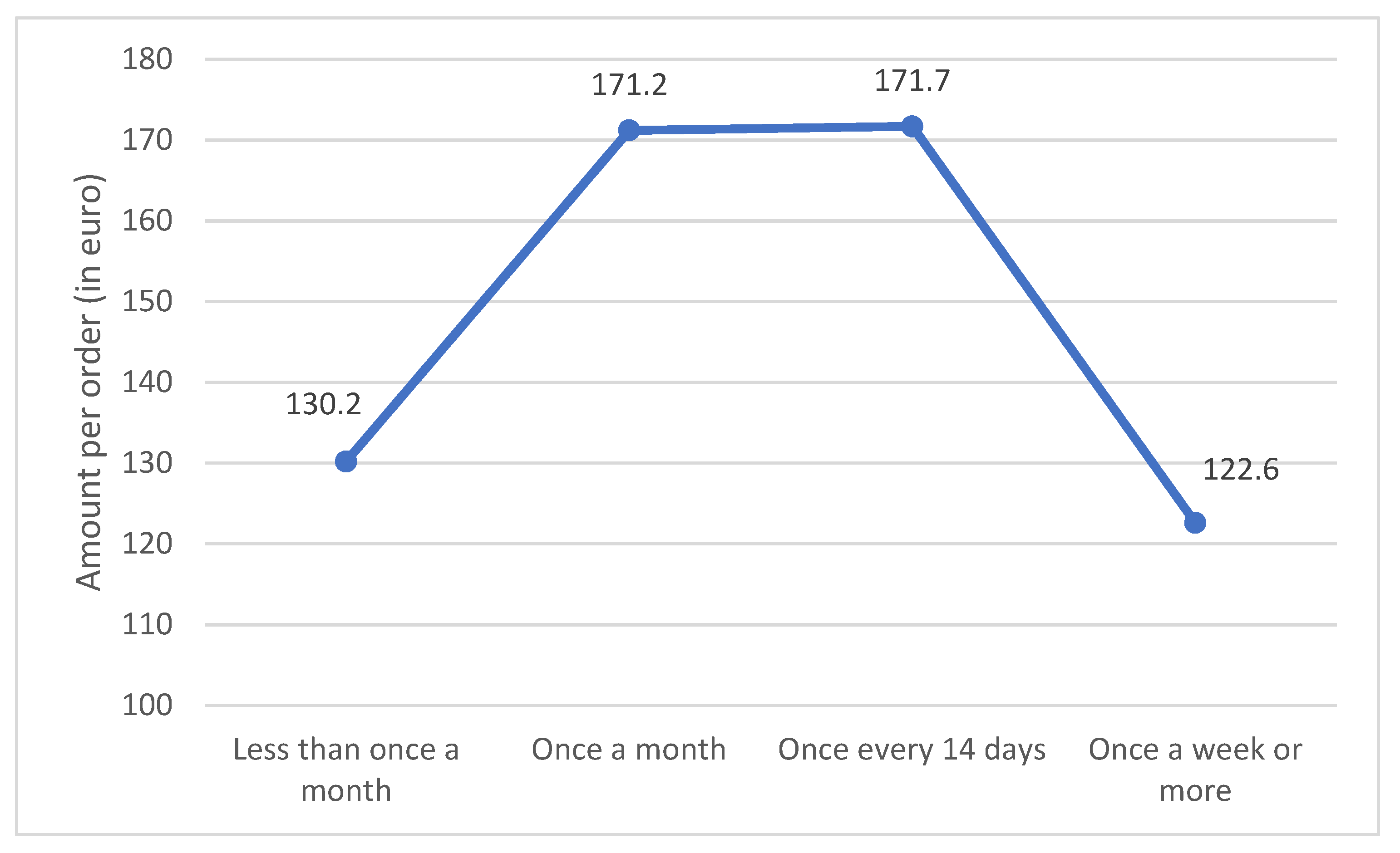

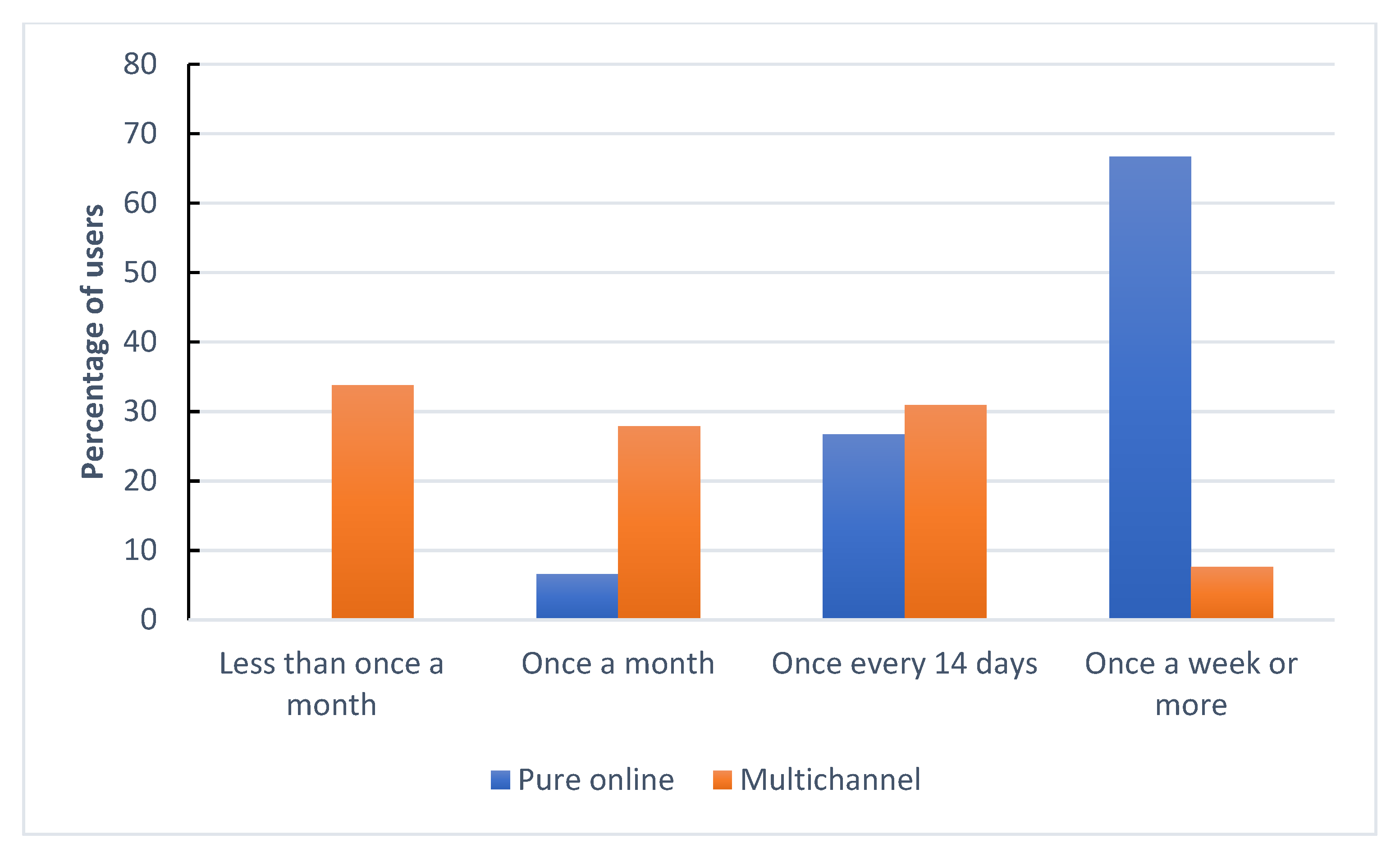

5.2. Grocery Shopping Behavior

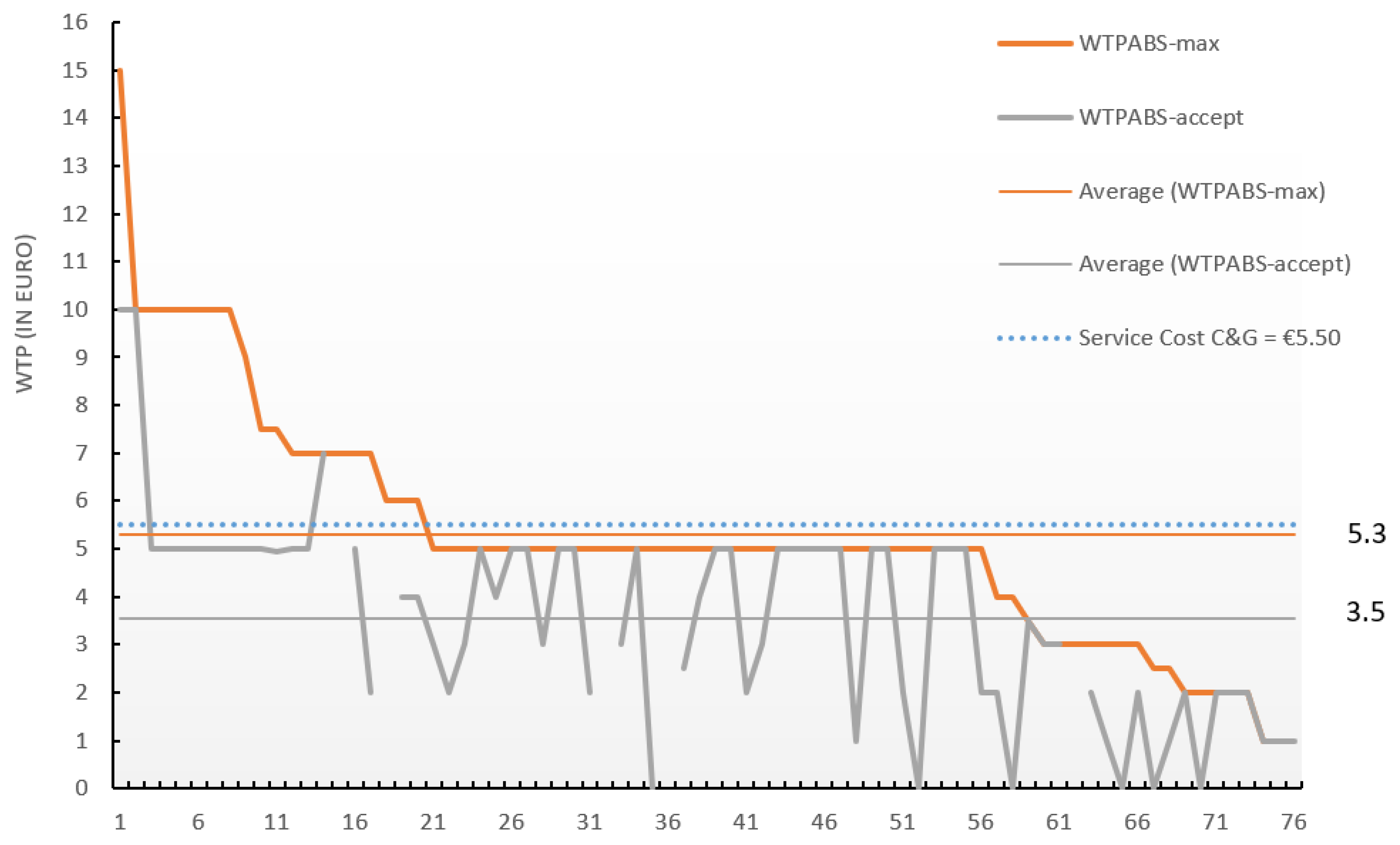

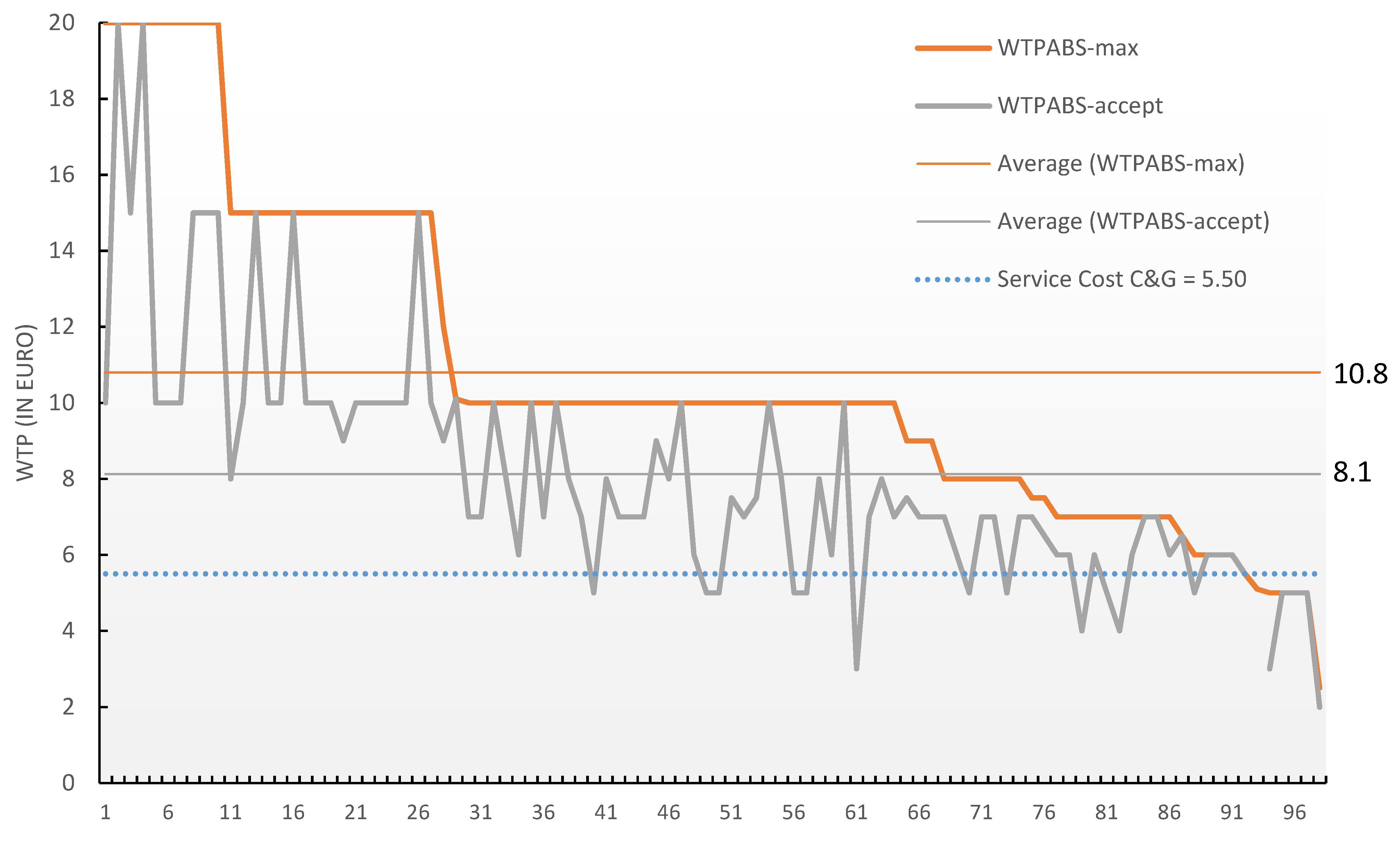

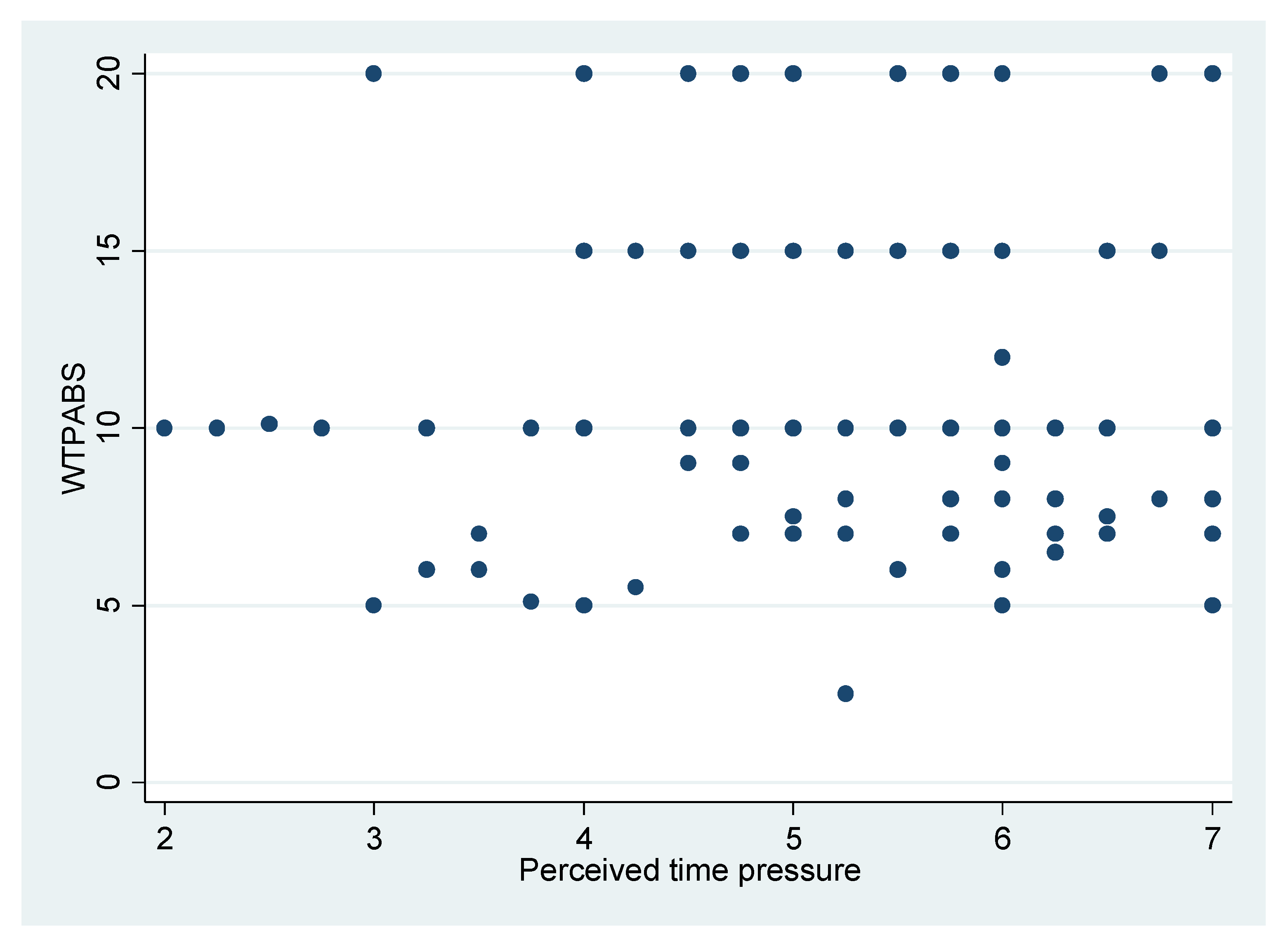

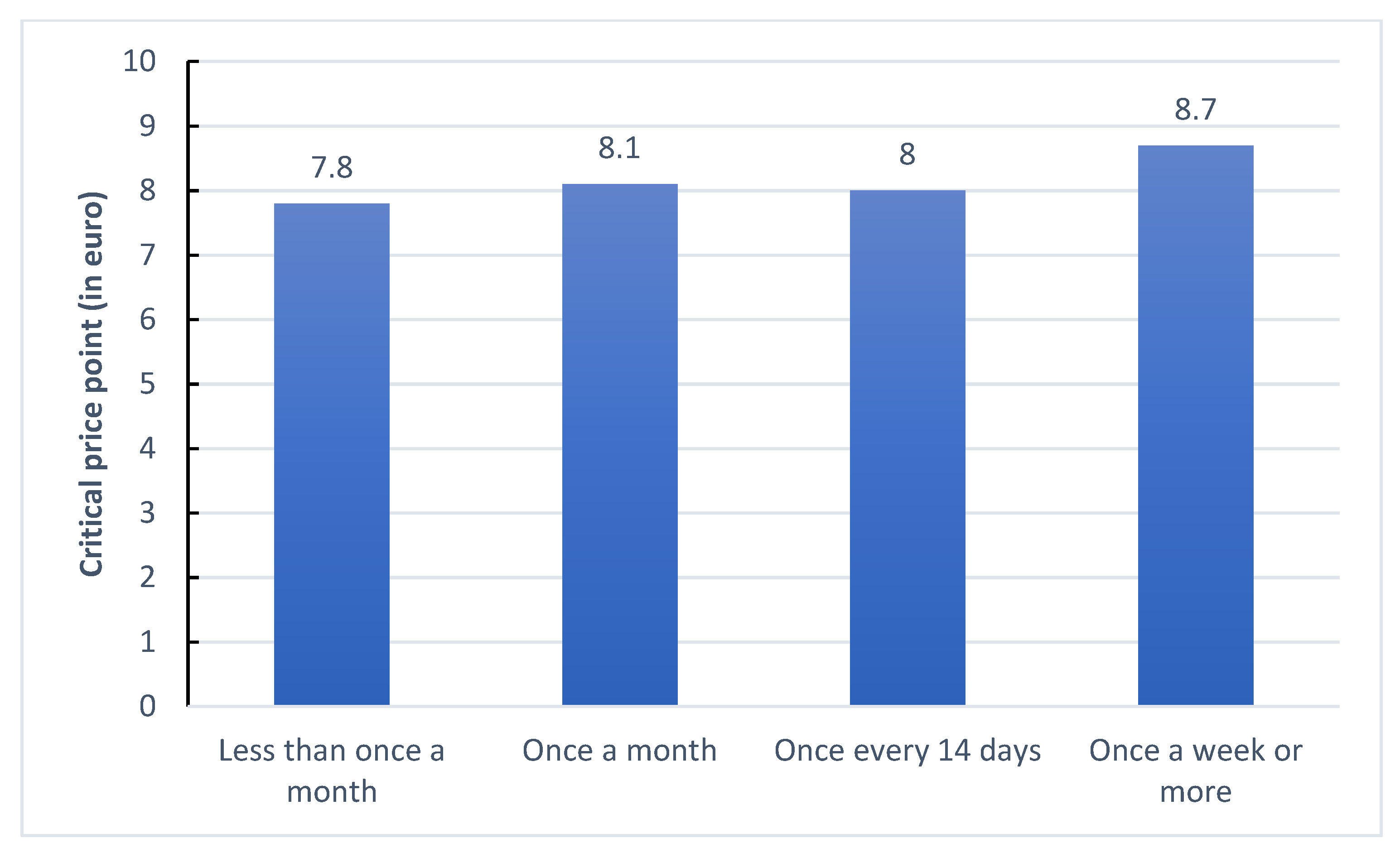

5.3. Willingness to Pay for Click-and-Collect Services

6. Regression Results

6.1. Full Sample

6.2. Respondents with a Non-Zero WTP

6.3. Users

7. Discussion

7.1. Level of Willingness to Pay

7.2. Determinants of PTP

7.3. Relationship between PTP and WTP

7.4. Other Determinants of WTP

7.5. Managerial Implications

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Multi-Item Scales

| Dull | Exciting |

| Not Fun | Fun |

| Not amusing | Amusing |

| Not enjoyable | Enjoyable |

Appendix A.2. Users’ Choice of Time Slots

| Fixed Time Slot? | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Day? | No Fixed Time Slot | 08:00–13:00 | 13:00–17:00 | 17:00–21:00 | Total |

| No fixed day | 19 | 6 | 6 | 16 | 47 |

| Monday | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 10 |

| Tuesday | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Wednesday | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 |

| Thursday | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Friday | 1 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 17 |

| Saturday | 0 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 13 |

| Total | 23 | 25 | 17 | 34 | 99 |

References

- Kämäräinen, V.; Saranen, J.; Holmström, J. The reception box impact on home delivery efficiency in the e-grocery business. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2001, 31, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, C. E-grocery as new innovative distribution channel in the German food retailing. In Proceedings of the Make-Learn International Conference 2013, Zadar, Croatia, 19–21 June 2013; pp. 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Hübner, A.H.; Kuhn, H.; Wollenburg, J. Last mile fulfilment and distribution in omni-channel grocery retailing: A strategic planning framework. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzab, H.; Teller, C. To pay or not to pay, that is the question. Conceptual model and empirical results on consumers’ view on home delivery. In Grocery E Commerce: Consumer Behavior and Business Strategies; Kornum, N., Bjerre, M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005; pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- IGD. Kaufland Exiting Online Channel. 2017. Available online: https://retailanalysis.igd.com/markets/europe/news/news-article/t/kaufland-exiting-online-channel/i/18085 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Eurostat. E-Commerce Statistics for Individuals. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=E-commerce_statistics_for_individuals (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Agatz, N.; Campbell, A.M.; Fleischmann, M.; Van Nunen, J.A.E.E.; Savelsbergh, M. Revenue management opportunities for Internet retailers. J. Revenue Pricing Manag. 2013, 12, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, R.; Korkmaz, E.; Sahin, O. Can Free-Shipping Hurt Online Retailers? Evidence from Online Grocery Shopping (Johns Hopkins Carey Business School Research Paper No.20-04). 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2506354 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Martín, J.C.; Pagliara, F.; Román, C. The Research Topics on E-Grocery: Trends and Existing Gaps. Sustainability 2019, 11, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goethals, F.; Leclercq-Vandelannoitte, A.; Tütüncü, Y. French consumers’ perceptions of the unattended delivery model for e-grocery retailing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2012, 19, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teller, C.; Kotzab, H.; Grant, D.B. The consumer direct services revolution in grocery retailing: An exploratory investigation. Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 2006, 16, 78–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, C.; Pokrivčák, J.; Tóth, M.; Plevný, M. Online grocery retailing in Germany: An explorative analysis. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18, 1243–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milioti, C.; Pramatari, K.; Zampou, E. Choice of prevailing delivery methods in e-grocery: A stated preference ranking experiment. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2021, 49, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, M.; Vyt, D.; Mevel, O.; Morvan, T.; Morvan, N. Measuring customers benefits of click and collect. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milioti, C.; Pramatari, K.; Kelepouri, I. Modelling consumers’ acceptance for the click and collect service. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyt, D.; Jara, M.; Cliquet, G. Grocery pickup creation of value: Customers’ benefits vs. spatial dimension. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielens, K.; Gijsbrechts, E.; Geyskens, I. Navigating the Last Mile: The Demand Effects of Click-and-Collect Order Fulfillment. J. Mark. 2021, 85, 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nott, G. Tipping Point: Can the Pandemic Reignite Grocery Click & Collect? 2020. Available online: https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/online/tipping-point-can-the-pandemic-reignite-grocery-click-and-collect/646501.article (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Belavina, E.; Girotra, K.; Kabra, A. Online Grocery Retail: Revenue Models and Environmental Impact. Manag. Sci. 2017, 63, 1781–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fikar, C.; Mild, A.; Waitz, M. Facilitating consumer preferences and product shelf life data in the design of e-grocery deliveries. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenburg, J.; Holzapfel, A.; Hübner, A.; Kuhn, H. Configuring Retail Fulfillment Processes for Omni-Channel Customer Steering. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2018, 22, 540–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J.L. A brief history of food retail. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltese, I.; Le Pira, M.; Marcucci, E.; Gatta, V.; Evangelinos, C. Grocery or @grocery: A stated preference investigation in Rome and Milan. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 87, 101096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Giannikas, V.; Han, Y.; Grover-Silva, E.; Qiao, B. Using customer-related data to enhance e-grocery home delivery. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raijas, A. The consumer benefits and problems in the electronic grocery store. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2002, 9, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, J.; Osman, M.C.; Hellström, D.; Vakulenko, Y. Customer expectations of unattended grocery delivery services: Mapping forms and determinants. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risberg, A.; Jafari, H. Last mile distribution practices in e-commerce: A framework development and empirical analysis. In Book of Proceedings: CERR2021; Brusset, X., Ed.; SKEMA Business School: Lille, France, 2021; pp. 229–234. ISBN 978-2-493066-00-8. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A.; Gülpınar, N.; Zheng, Y. Dynamic pricing of flexible time slots for attended home delivery. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 294, 1022–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, C.D. Grocery Pick Up Is Here to Stay. Here’s How It Is Evolving. 2020. Available online: https://www.grocerydive.com/news/grocery-pickup-is-here-to-stay-heres-how-its-evolving/587702/ (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Jensen, K.L.; Yenerall, J.; Chen, X.; Yu, T.E. US Consumers’ Online Shopping Behaviors and Intentions During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey. The Path Forward for European Grocery Retailers. 2021. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-path-forward-for-european-grocery-retailers (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Picot-Coupey, K.; Huré, E.; Cliquet, G.; Petr, C. Grocery shopping and the Internet: Exploring French consumers’ perceptions of the ‘hypermarket’ and ‘cybermarket’ formats. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2009, 19, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, E.; Van Hove, L. Adoption of Online Grocery Shopping: Personal or Household Characteristics? J. Internet Commer. 2017, 16, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, E.; Van Hove, L. Triggered or evaluated? A qualitative inquiry into the decision to start using e-grocery services. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2020, 30, 103–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, M.T. Relation of consumers’ buying habits to marketing methods. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1923, 1, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Seiders, K.; Voss, G.B.; Grewal, D.; Godfrey, A.L. Do satisfied customers buy more? Examining moderating influ-ences in a retailing context. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfinbarger, M.; Gilly, M.C. Shopping Online for Freedom, Control, and Fun. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale, L.; Venkatesh, A. Toward the construct of convenience in consumer research. In Advances in Consumer Research; Lutz, R.J., Ed.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1986; Volume 13, pp. 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Seiders, K.; Berry, L.L.; Gresham, L. Attention retailers: How convenient is your convenience strategy? Sloan Manag. Rev. 2000, 49, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L.L.; Seiders, K.; Grewal, D. Understanding Service Convenience. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiders, K.; Voss, G.B.; Godfrey, A.L.; Grewal, D. SERVCON: Development and validation of a multidimensional service convenience scale. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2007, 35, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, M.B.; Ponder, N. Perceptions of retail convenience for in-store and online shoppers. Mark. Manag. J. 2010, 20, 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Jun, M. Measuring consumer perceptions of online shopping convenience. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernot, D. Internet shopping for Everyday Consumer Goods: An examination of the purchasing and travel practices of click and pickup outlet customers. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 87, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couclelis, H. Pizza over the Internet: E-commerce, the fragmentation of activity and the tyranny of the region. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2004, 16, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, E.; Van Hove, L. Intra-household task allocation in online grocery shopping: Together alone. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S.; Mendez, F. Perceived Ubiquity in Mobile Services. J. Interact. Mark. 2013, 27, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, H.B.; Mommens, K.; Verlinde, S.; Macharis, C. How Does Consumers’ Omnichannel Shopping Behaviour Translate into Travel and Transport Impacts? Case-Study of a Footwear Retailer in Belgium. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suel, E.; Polak, J.W. Incorporating online shopping into travel demand modelling: Challenges, progress, and opportunities. Transp. Rev. 2018, 38, 576–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Kwan, M.-P. The Internet, mobile phone and space-time constraints. Geoforum 2008, 39, 1362–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gahinet, M.-C.; Cliquet, G. Proximity and time in convenience store patronage: Kaïros more than chronos. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, C.; Schwanen, T.; Anable, J. ‘Online Omnivores’ or ‘Willing but struggling’? Identifying online grocery shopping behavior segments using attitude theory. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepek, M.; Bauerová, R. Why do retail customers hesitate for shopping grocery online? Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2020, 26, 1444–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, D.; Fernie, J.; Schulz, B. Exploring Success Factors and Constraints in German Online Food Retailing; Rencontres Internationales de la Recherche en Supply Chain et Logistique (RIRL): Marseille, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- de Magalhães, D.J.A.V. Analysis of critical factors affecting the final decision-making for online grocery shopping. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 87, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garver, M.S.; Williams, Z.; Taylor, G.S.; Wynne, W.R. Modelling choice in logistics: A managerial guide and application. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; De Leeuw, S.; Dullaert, W.; Foubert, B.P.J. What Is the Right Delivery Option for You? Consumer Preferences for Delivery Attributes in Online Retailing. J. Bus. Logist. 2019, 40, 299–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. The time-buying consumer. J. Retail. 1979, 55, 58–68. [Google Scholar]

- Godinho, S.; Prada, M.; Garrido, M.V. Under Pressure: An Integrative Perspective of Time Pressure Impact on Consumer Decision-Making. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2016, 28, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reutskaja, E.; Nagel, R.; Camerer, C.F.; Rangel, A. Search Dynamics in Consumer Choice under Time Pressure: An Eye-Tracking Study. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 900–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornik, J. The Temporal Dimension of Shopping Behavior. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2021, 14, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, J.D.; Capella, L.M. Shopper reactions to perceived time pressure. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 1995, 23, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.; Gärling, T.; Marell, A. Effects of time pressure, type of shopping, and store attributes on consumers’ satisfaction with grocery shopping. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 334–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kenhove, P.; De Wulf, K. Income and time pressure: A person-situation grocery retail typology. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2000, 10, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T. Determinants of consumers’ repeat online buying of groceries. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2006, 16, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Oppewal, H. Why consumers hesitate to shop online: An experimental choice analysis of grocery shopping and the role of delivery fees. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2006, 34, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Langerak, F. Possible determinants of consumers’ adoption of electronic grocery shopping in the Netherlands. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2001, 8, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, K.; Campo, K.; Lamey, L.; Breugelmans, E. A Bigger Slice of the Multichannel Grocery Pie: When Does Consumers’ Online Channel Use Expand Retailers’ Share of Wallet? J. Retail. 2016, 92, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. A Theory of the Allocation of Time. Econ. J. 1965, 75, 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVoe, S.E.; House, J. Time, money, and happiness: How does putting a price on time affect our ability to smell the roses? J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVoe, S.E.; Pfeffer, J. When time is money: The effect of hourly payment on the evaluation of time. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 104, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamermesh, D.S.; Lee, J. Stressed Out on Four Continents: Time Crunch or Yuppie Kvetch? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2007, 89, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, E.M.; Hoch, S.J. Spending Time versus Spending Money. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, T.A.; van der Horst, K.; Siegrist, M. Convenience food products. Drivers for consumption. Appetite 2010, 55, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer, M.; McCarthy, M.; Cowan, C.; Ryan, I. The influence of lifestyle characteristics and beliefs about convenience food on the demand for convenience foods in the Irish market. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, M.D. Working Wives and Convenience Consumption. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 8, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, S.; Klose, S.; Ettinger, A. Linking service convenience to satisfaction: Dimensions and key moderators. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 31, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Chen, M.; Hsu, C.; Kuo, N. The effect of service convenience on post-purchasing behaviours. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2010, 110, 1420–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; e Silva, S.C.; Ferreira, M.B. How convenient is it? Delivering online shopping convenience to enhance customer satisfaction and encourage e-WOM. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaura, V.; Prasad, C.S.D.; Sharma, S. Service quality, service convenience, price and fairness, customer loyalty, and the mediating role of customer satisfaction. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijnen, M.; de Ruyter, K.; Wetzels, M. An assessment of value creation in mobile service delivery and the moderating role of time consciousness. J. Retail. 2007, 83, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Koschate, N.; Hoyer, W.D. Do Satisfied Customers Really Pay More? A Study of the Relationship between Customer Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, P.; Moeller, S.; Pibernik, R. Paying for convenience. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2012, 42, 584–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, S.S.; Anderson, R.; Ponnavolu, K. Customer loyalty in e-commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herhausen, D.; Binder, J.; Schoegel, M.; Herrmann, A. Integrating Bricks with Clicks: Retailer-Level and Channel-Level Outcomes of Online–Offline Channel Integration. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Zhuang, G.; Li, S. Will Consumers Pay More for Efficient Delivery? An Empirical Study of What Affects E-Customers’ Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay on Online Shopping in Bangladesh. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.S.H.; Ahammad, M.F. Antecedents and consequences of online customer satisfaction: A holistic process perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 124, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etkin, J.; Evangelidis, I.; Aaker, J. Pressed for Time? Goal Conflict Shapes how Time is Perceived, Spent, and Valued. J. Mark. Res. 2015, 52, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.T.; Vancouver, J.B. Goal constructs in psychology: Structure, process, and content. Psychol. Bull. 1996, 120, 338–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechtl, H. Adoption of online shopping by German grocery shoppers. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2003, 13, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alreck, P.L.; DiBartolo, G.R.; Diriker, M.; Dover, H.F.; Passyn, K.A.; Settle, R.B. Time Pressure, Time Saving and Online Shopping: Exploring a Contradiction. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2009, 25, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cha, S.E.; Suh, J. Social acceleration vs. slowdown: Who became less busy in Korea? And why? Dev. Soc. 2017, 46, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, H.; Zheng, J. The Relationship Between Economic Value of Time and Feelings of Time Pressure. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1395–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVoe, S.E.; Pfeffer, J. Time is tight: How higher economic value of time increases feelings of time pressure. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamermesh, D.S. Time use—Economic approaches. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2019, 26, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wertenbroch, K.; Brendl, C.M. The Value Heuristic in Judgments of Relative Frequency. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, L.A.; Hicks, J.A.; Abdelkhalik, J. Death, Life, Scarcity, and Value: An Alternative Perspective on the Meaning of Death. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 1459–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southerton, D. Analysing the Temporal Organization of Daily Life. Sociology 2006, 40, 435–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddelmeyer, H.; Hamermesh, D.S.; Wooden, M. THE stress cost of children on moms and dads. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2018, 109, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katt, F.; Meixner, O. A systematic review of drivers influencing consumer willingness to pay for organic food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, R.; Bokelmann, W.; Gowdru, N.V.; Dias, G. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Organic Fruits and Vegetables: Empirical Evidence from a Consumer Survey in India. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loopmans, M.; Van Hecke, E.; De Craene, V.; Martens, M.; Schreurs, J.; Oosterlynck, S. Selectie van Kleinstedelijke Gebieden in Vlaanderen. 2011. Available online: http://www2.vlaanderen.be/ruimtelijk/docs/Studie_kleinstedelijkegebieden.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2014).

- Miller, K.M.; Hofstetter, R.; Krohmer, H.; Zhang, Z.J. How Should Consumers’ Willingness to Pay be Measured? An Empirical Comparison of State-of-the-Art Approaches. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlömert, N.; Eggers, F. Predicting new service adoption with conjoint analysis: External validity of BDM-based incentive-aligned and dual-response choice designs. Mark. Lett. 2016, 27, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carare, O.; McGovern, C.; Noriega, R.; Schwarz, J. The willingness to pay for broadband of non-adopters in the U.S.: Estimates from a multi-state survey. Inf. Econ. Policy 2015, 30, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, E.R.; Voss, K.E.; Crowley, A.E. Measuring the hedonic and utilitarian dimensions of attitude: A generally applicable scale. Adv. Consum. Res. 1997, 24, 235–241. [Google Scholar]

- Vandeschrick, C.; Sanderson, J.-P. De Verdeling van de Huishoudelijke Taken: Misschien Evoluties, Maar Zeker Ook Weerstand. GGP Belgium Policy Brief, 6. 2013. Available online: http://www.ggps.be/doc/PB_6_NL.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- Harris, P.; Robinson, H.; Riley, F.D.; Hand, C. Consumers’ multi-channel shopping experiences in the UK grocery sector: Purchase behaviour, motivations and perceptions: An extended abstract. In Marketing at the Confluence between Entertainment and Analytics, Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science; Rossi, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- De Bock, J. Delhaize Opent Eerste Drive in Overijse. 2016. Available online: http://www.gondola.be/nl/news/retail/delhaize-opent-eerste-drive-overijse (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Sinnaeve, S. Carrefour Met Bpost in Online Boodschappen. 2017. Available online: http://www.tijd.be/ondernemen/retail/Carrefour-met-Bpost-in-onlineboodschappen/9850919 (accessed on 1 December 2021).

- Eekhout, I.; de Vet, H.C.; Twisk, J.W.; Brand, J.P.; de Boer, M.; Heymans, M. Missing data in a multi-item instrument were best handled by multiple imputation at the item score level. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morganosky, M.A.; Cude, B.J. Consumer response to online grocery shopping. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2000, 28, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintagunta, P.K.; Chu, J.; Cebollada, J. Quantifying Transaction Costs in Online/Off-line Grocery Channel Choice. Mark. Sci. 2012, 31, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, M.B.; Elliott, G. Role of demographics, social connectedness and prior internet experience in adoption of online shopping: Applications for direct marketing. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2011, 19, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Definition | Applied to Online Grocery Shopping |

|---|---|---|

| Access convenience | The speed and ease with which consumers can reach a retailer. |

|

| Search convenience | The speed and ease with which consumers can identify and select products they wish to buy. |

|

| Evaluation convenience | The speed and ease with which consumers can access detailed yet easy-to-understand product descriptions. |

|

| Transaction convenience | The speed and ease with which consumers can effect or amend transactions. |

|

| Possession (post-purchase) convenience | The speed and ease with which consumers can obtain desired products. |

|

| Country | Year | Data | Delivery Type | Main Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kotzab and Teller [4] | Austria | 2002 | Face-to-face interviews with customers of an offline supermarket in the city center of Vienna (n = 308). Standardized questionnaire. | Attended home delivery | We found that 25.3% was not prepared to pay anything. In a multiple regression analysis among respondents with a non-zero WTP only ‘perceived transportation costs’ proved significant. Note that the majority estimated these costs to be zero. No impact of ‘shopping frequency’, ‘basket size’ or ‘perceived distance’. |

| Teller et al. [11] | Austria | 2005 | Web-based survey among two specific consumer groups: the ‘time-starved’ (n = 384) and the ‘new technologists’ (n = 144). Time-starved: “Dual income household with kids, time pressed” New technologists: “Young and technologically interested, have no time for shopping” | Attended home delivery | The time-starved were prepared to pay a significantly higher fee (modus = EUR 5) than the new technologists (modus = EUR 2). For both groups, significant but weak correlations (of maximum 0.42) were found with ‘distance from home to store’, ‘size of shopping basket’, ‘average shopping frequency’, and ‘degree of procurement responsibility’ (i.e., the share of the household’s grocery shopping done by the respondent). Interestingly, no relationship was found between household income and WTP. |

| Goethals et al. [10] | France | 2009 | Structured survey, face-to-face (n = 68) and online (n = 177). | Unattended home delivery | The majority had not yet bought groceries online (83%); 32% has WTP of zero. The relationship between distance to the store and consumers’ WTP was significantly negative. No impact of ‘shopping time’ (how long it takes a consumer to grocery shop) and ‘in-store shopping pleasure’. Interaction effect between ‘in-store shopping pleasure’ and ‘shopping time’ is significant and positive. |

| Gil et al. [8] | Europe | 2008–2009 | Transaction data of 29,373 customers (913,842 transactions). | Attended home delivery (consumers pay a time-specific delivery fee, ranging from EUR 4.95 to 11.95). | Delivery fee is positively correlated with basket size and negatively with the number of times the service is used per year. |

| Seitz et al. [12] | Germany | 2012–2013 | Structured survey (n = 412), mainly among non-users; 89.8% of the respondents were not even familiar with the concept of e-grocery buying. | Attended home delivery; pick-up; drive-through. | 84.5% was prepared to pay for home delivery, 36.2% for pick-up, and 36.7% for drive-through. Being willing to pay is positively related to ‘basket size’, ‘income’, and ‘need for convenience’. |

| Milioti et al. [13] | Greece and UK | 2016 | Online questionnaire (Greece: n = 170; UK: n = 367). Sample consists of consumers that have shopped for groceries online at least once. | Attended home delivery; pick-up from store; pick-up from a locker. (Pick-up from store = reference category) | Home delivery holds a strong position among the distribution modes examined, especially concerning the weekly order, while pick-up from locker can be developed to a competitive alternative for urgent orders in both markets. Greece: in a weekly (urgent) order setting, consumers are willing to pay an additional fee of EUR 3.64 (EUR 3.26) for home delivery and an additional fee of EUR 1.69 (EUR 1.79) for the pick-up from locker option compared to pick up from the store. UK: in a weekly (urgent) order setting, consumers are willing to pay an additional fee of EUR 6.46 (EUR 4.42) for home delivery and an additional fee of EUR 1.65 (EUR 1.97) for the pick-up from locker option. ‘Price consciousness’ has a negative impact and ‘satisfaction with delivery fulfilment’ positively influences WTP measures. Time pressure is not significant. |

| Brand et al. [52] | UK | 2017 | Online survey among 2032 grocery shoppers. | Attended home delivery | The majority disagreed with the statement ‘I would pay more for the convenience of home delivery of groceries’ (score of 2.52 on a 1–5 scale). |

| Klepek and Bauerova [53] | Czech Republic | unknown | Web-based survey (n = 670). Open question: “Why do you not buy groceries online?” Data collection by IPSOS (online panel). | Not specified | Content analysis identified ‘unwillingness to pay for delivery’ as one of the thematic units. Theme was ranked 8th out of 14 and frequency analysis showed that 23 out of 945 responses (2.4%) related to consumers’ unwillingness to pay. |

| DV: PTP (n = 543) | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Robust Std. Err. | Beta | |||

| Constant | 3.993 *** | 0.349 | 11.46 | ≤0.001 | |

| Young children (H1) | 0.564 *** | 0.149 | 0.159 *** | 3.79 | ≤0.001 |

| Employment (H2) | 0.727 *** | 0.150 | 0.220 *** | 4.86 | ≤0.001 |

| Household income (H3) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.071 | 1.73 | 0.083 |

| Education (H4) | 0.098 * | 0.039 | 0.098 * | 2.50 | 0.013 |

| Age (H5) | −0.019 *** | 0.004 | −0.197 *** | −4.28 | ≤0.001 |

| F (5, 537) = 36.11; p ≤ 0.001 | |||||

| R2 = 0.252 | |||||

| Root MSE = 1.226 | |||||

| DV: WTPABS (n = 543) | |||||

| Constant | −3.827 ** | 1.444 | −2.65 | 0.008 | |

| PTP_predicted (H6) | 1.840 *** | 0.290 | 0.278 *** | 6.34 | ≤0.001 |

| PSE (H7) | −0.591 *** | 0.150 | −0.162 *** | −3.94 | ≤0.001 |

| Household income (H8) | 0.000 * | 0.000 | 0.090 * | 2.09 | 0.037 |

| F (3, 539) = 34.04; ≤0.001 | |||||

| R2 = 0.159 | |||||

| Root MSE = 4.307 | |||||

| DV: PTP (n = 174) | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Robust Std. Err. | Beta | |||

| Constant | 4.436 *** | 0.611 | 7.26 | ≤0.001 | |

| Young children (H1) | 0.439 * | 0.201 | 0.165 * | 2.18 | 0.030 |

| Employment (H2) | 0.564 * | 0.264 | 0.175 * | 2.14 | 0.034 |

| Household income (H3) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.035 | 0.45 | 0.653 |

| Education (H4) | 0.144 | 0.077 | 0.136 | 1.87 | 0.063 |

| Age (H5) | −0.019 * | 0.008 | −0.195 * | −2.34 | 0.020 |

| F (5, 168) = 8.25; p ≤ 0.001 | |||||

| R2 = 0.197 | |||||

| Root MSE = 1.160 | |||||

| Coefficient | Std. Err. | z | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Equation (WTPABS) | ||||

| PTP_predicted | 0.260 | 1.074 | 0.24 | 0.809 |

| PSE | −0.166 | 0.252 | −0.66 | 0.512 |

| Household income | 0.001 * | 0.000 | 2.36 | 0.018 |

| Constant | 6.664 | 7.129 | 0.93 | 0.350 |

| Selection Equation (non-zero WTP) | ||||

| Education | 0.085 | 0.047 | 1.81 | 0.070 |

| Age | −0.020 *** | 0.005 | −4.12 | ≤0.001 |

| Children | 0.415 ** | 0.157 | 2.63 | 0.008 |

| Employment | 0.176 | 0.164 | 1.07 | 0.285 |

| Household income | 0.000 * | 0.000 | 2.52 | 0.012 |

| Constant | −0.517 | 0.394 | −1.31 | 0.189 |

| Athrho | −0.225 | 0.380 | −0.59 | 0.555 |

| Wald Chi2 = 5.88 (p = 0.118) Log Likelihood = −781.340 |

| DV: PTP (n = 98) | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Robust Std. Err. | Beta | |||

| Constant | 3.424 *** | 0.936 | 3.66 | ≤0.001 | |

| Young children (H1) | 0.636 * | 0.260 | 0.258 * | 2.45 | 0.016 |

| Employment (H2) | 0.880 * | 0.364 | 0.250 * | 2.42 | 0.018 |

| Household income (H3) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.089 | 0.80 | 0.428 |

| Education (H4) | 0.113 | 0.109 | 0.104 | 1.04 | 0.302 |

| Age (H5) | −0.002 | 0.014 | −0.015 | −0.12 | 0.905 |

| F (5, 92) = 4.48; p = 0.001 | |||||

| R2 = 0.196 | |||||

| Root MSE = 1.137 | |||||

| WTPABS (a) | WTPREL (b) | WTPTOT (c) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Equation | |||

| PTP_observed | 0.368 (0.95) | −0.526 (−0.65) | 29.188 * (2.48) |

| PSE | 0.535 (1.56) | 1.442 (1.92) | −13.657 (−1.34) |

| Household income | 0.000 (1.23) | −0.001 (−1.86) | 0.019 (1.74) |

| Multichannel | −1.107 (−1.17) | −1.033 (−0.49) | −228.214 *** (−8.19) |

| Constant | 3.215 (0.69) | 14.854 (1.89) | 129.603 (0.86) |

| Selection Equation (non-zero WTP) | |||

| Education | 0.111 * (1.99) | 0.109 (1.86) | 0.118 * (1.97) |

| Age | −0.020 ** (−3.11) | −0.023 *** (−3.49) | −0.022 *** (−3.55) |

| Children | 0.568 *** (3.54) | 0.505 ** (2.72) | 0.532 *** (3.21) |

| Employment | 0.165 (0.87) | 0.188 (0.95) | 0.145 (0.72) |

| Household income | 0.000 *** (3.23) | 0.000 *** (4.26) | 0.000 *** (4.22) |

| Constant | −1.590 *** (−3.41) | −1.455 ** (−3.05) | −1.518 *** (−3.18) |

| Athrho | 0.612 (1.43) | −0.107 (−0.38) | 0.307 (0.65) |

| Wald Chi2 | 4.48 | 8.40 | 96.67 |

| P | 0.345 | 0.078 | ≤0.001 |

| Log Likelihood | −488.006 | −564.650 | −818.572 |

| Censored | 445 | 445 | 445 |

| Uncensored | 98 | 98 | 98 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Van Droogenbroeck, E.; Van Hove, L. Are the Time-Poor Willing to Pay More for Online Grocery Services? When ‘No’ Means ‘Yes’. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 253-290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17010013

Van Droogenbroeck E, Van Hove L. Are the Time-Poor Willing to Pay More for Online Grocery Services? When ‘No’ Means ‘Yes’. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2022; 17(1):253-290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleVan Droogenbroeck, Ellen, and Leo Van Hove. 2022. "Are the Time-Poor Willing to Pay More for Online Grocery Services? When ‘No’ Means ‘Yes’" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 17, no. 1: 253-290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17010013

APA StyleVan Droogenbroeck, E., & Van Hove, L. (2022). Are the Time-Poor Willing to Pay More for Online Grocery Services? When ‘No’ Means ‘Yes’. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 17(1), 253-290. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer17010013