Abstract

Influencer marketing acquires customers who follow their favorite celebrities, who have shared beliefs and opinions. This research explores the self-motives and influencer-related factors that lead to influencer congruence. Influenced customers subsequently recommend those influencers to others. No concrete scale of recommendation is available so far. This research also conceptualizes, develops, and validates a scale for recommendations. In this study, 451 respondents answered questions about the influencers they follow. Normality, reliability, and validity were used for hypothesis testing. Results show the positive and direct impacts of all proposed hypotheses. The findings contribute to the literature by presenting a balanced approach to studying two parallel yet integral aspects of influencer marketing: the influencer and the consumer.

1. Introduction

Social media’s unparalleled integration in people’s routines has allowed marketers to communicate innovatively [,]. One unprecedented approach, influencer marketing, involves collaborating with prominent social media influencers to promote products and services []. This kind of marketing is targeted at both potential and actual customers [,]. By means of their attractive and authentic personas, social media influencers develop images that resonate with consumers and are replicated in their lifestyles and brand preferences [,,]. According to a previous study [], consumers are keenly aware of goods and services related to their value (this is known as self-congruence). However, the authors of [] established that the marketing literature is scarce in terms of its exploration of self-congruence. Similarly, the effectiveness of various aspects of influencers proceeds from the importance of the domain itself. Therefore, the expansion of influencer endorsement is critical for marketers and calls for further research on how brands can effectively benefit from influencer marketing.

Previous research has investigated self-congruence in the context of celebrities, brands, destinations, services, and products [,,,]. However, despite the growing significance of influencer marketing [], only a few studies [,] have analyzed the impact of self-influencer congruence. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, very few studies have examined the overall impact of both consumer- and influencer-related factors that determine self-influencer congruence. The current study will fill this gap by identifying and evaluating the consumer- and influencer-based factors that lead to self-influencer congruence.

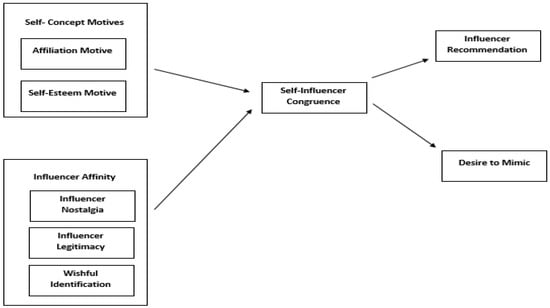

The current study has three objectives. First, it aims to identify the consumer-related (self-concept motives) and influencer-related factors that lead to self-influencer congruence. The previous literature mentions variables such as social desirability, status consumption, avoidance of similarity, trustworthiness, expertise, attractiveness, respect, and similarity as antecedents of self-congruence [,]. However, no study has simultaneously explored consumer- and influencer-related factors that lead to self-influencer congruence. This study fills this gap by observing self-concept motives as consumer-related factors and influencer affinity as influencer-related factors. Previous researchers have examined the self-concept motives in consumer behavior to show how individuals view themselves regarding the product or brand personality []. Nevertheless, the present study is the first to observe affiliation and self-esteem as self-concept motives for influencer congruence. Similarly, this research is the first to study the connection between influencer affinity and influencer congruence in the context of influencer nostalgia, influencer legitimacy, and wishful identification.

The second objective is to discover how self-influencer congruence leads to consumers’ desire to mimic and influencer recommendations. Previous studies have signified that consumers mimic the actions of influencers who they perceive as role models []. On the other hand, when consumers identify with a product, brand, or endorser, they are more prone to recommend it [,]. As a result, this research establishes that when individuals feel connected to social media influencers, they recommend them and show a desire to mimic them.

This study’s third and final objective is to conceptualize, develop, and validate a scale of brand recommendation that can be used to measure the outcome variable of influencer recommendation. Numerous studies have observed recommendations as a variable; most researchers have used scales based on word of mouth (WOM) [,,]. Regardless of the importance of brand recommendations, no concrete scale has been developed to measure influencer recommendations. Hence, the scale development process explained by [] was used to establish a suitable scale. Ultimately, a scale of eight items was proposed and empirically validated.

The findings of the present study contribute to the literature by elucidating a balanced approach to studying two parallel yet integral aspects of influencer marketing: the influencer and the consumer. Further, self-congruence is associated with actions that lack adequate reinforcement. Additionally, a validated scale on recommendations reinforces the importance of the newly conceptualized variable. Similarly, this study encourages marketing experts to utilize the prominent, demanding, and advancing influencer marketing approach to accentuate the positive repercussions of their branding strategies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Background

Consumers prefer brands that reflect their self-concept. Consumer perception can be analyzed and examined based on self-congruity theory. Research indicates that consumers feel a sense of affiliation and identification with specific groups or brands based on their characteristics [,]. Due to this affiliation, consumers establish favorable attitudes towards certain brands, enhancing their self-congruence and purchase intentions. The literature [,,] shows that consumers are likely to imitate and recommend brands and products that resemble their expression of self.

2.2. Self-Congruity Theory

Self-congruity illustrates the extent to which an individual perceives a product or brand as consistent with how they perceive themselves []. According to self-congruity theory, consumers are more likely to pay attention to and purchase products from brands that reflect their self-concept []. Hence, the more similar a consumer feels they are to a brand, the more they will prefer that brand, as its symbolic values emphasize their self-perception []. This pattern indicates that consumer behavior is influenced by the cognitive harmony between their self-concept and a brand’s value-expressive characteristics []. Later, the authors of [] stated that self-congruity influences consumers and establishes trust in and satisfaction with brands or products. Hence, in light of self-congruity theory, the current study demonstrates that people follow certain influencers on social media to feel a sense of connection.

The present study’s primary goal is to investigate the influence of self-congruity on consumer behavior. This research examines the impact of self-congruity (based on consumers’ choices) on the likelihood that consumers will recommend and desire to mimic an influencer. The proposed conceptual framework is aligned with self-congruity theory and assists in elaborating the critical antecedents and outcomes of self-influencer congruence.

2.3. Hypotheses Construction

2.3.1. Self-Esteem and Self-Influencer Congruence

Self-esteem is a fundamental self-concept motive that causes people to seek out experiences that improve their self-concept []. As such, consumers purchase from brands that support their self-esteem []. Research on celebrity endorsers shows that self-esteem needs to be enhanced for such endorsements to work. As a result, celebrities are viewed as being linked to the emotions of human beings as they nourish their ideal selves [,]. Another study [] found that consumers who value their self-esteem are inclined to engage with products endorsed by celebrities with whom they identify. However, the authors of [] found that people with low self-esteem are likely to use social media, for example, Facebook. A positive attitude is generated by customers’ self-esteem, which, in turn, influences self-influencer congruence []. Therefore, it can be concluded that self-esteem is highly correlated with self-influencer congruence. Hence, the following hypothesis was formed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Self-esteem has a positive impact on self-influencer congruence.

2.3.2. Affiliation and Self-Influencer Congruence

Consumers’ self-concepts are also influenced by affiliation []. In [], affiliation is defined as the formation and maintenance of positive, vital, and long-lasting relationships among people. Similarly, in [], affiliation is defined as the degree to which people like communicating and making acquaintances. Affiliation also relates to a consumer’s desire to form relationships with brand-related communities if a brand aligns with their beliefs, tastes, and lifestyle []. According to a sports marketing study, supporters and viewers identify with people who share their values [].

According to the principles of social identity theory [], the psychological segregation among the self and others fades when people experience social identification with an individual or community []. Through this affiliation, the in-group members’ self-esteem is elevated as they differentiate themselves from out-groups.

Regarding celebrities, the social identification of followers generates a delusion of interactivity, making it easy for celebrities to influence them socially []. Influencers (who are a type of celebrity known as micro-celebrities) have a similar effect on their followers []. A consumer’s degree of affiliation positively influences self-influencer congruence as they establish relationships with influencers based on their similar preferences and lifestyles. Hence, it is reasonable to propose the following:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Affiliation has a positive impact on self-influencer congruence.

2.3.3. Influencer Nostalgia and Self-Influencer Congruence

Nostalgia does not occur only for the things or places an individual has used or visited but also for objects or locations that enable individuals to connect with something belonging to their past []. In the marketing literature, the term “nostalgic brands” refers to companies with which consumers can associate their past values, which consequently allows them to materialize their memories [].

Today, marketers often utilize the concept of nostalgia for advertising as consumers regard brands as more authentic when they demonstrate consumers’ previous beliefs and views [,]. Research reveals that when consumers feel nostalgia towards a brand, their self-congruence strengthens due to the memories, feelings, and emotions that are evoked []. The literature [,,] shows that nostalgia is highly effective in attracting consumers. Hence, it can be inferred that the more nostalgic an individual feels towards an influencer, the stronger the self-influencer congruence will be. Based on this, the following hypothesis was generated:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Influencer nostalgia has an impact on self-influencer congruence.

2.3.4. Influencer Legitimacy and Self-Influencer Congruence

According to [], legitimacy indicates congruence between the conduct of a legitimate body and a community’s shared values, thus making legitimacy dependent on a group. The literature [] also suggests that legitimacy is a resource acquired by an individual, brand, or company that others evaluate instead of the legitimized entity. Over time, brands obtain identities and values by exhibiting specific cultural beliefs, allowing them to achieve legitimacy as an authentic and congruent image in consumers’ minds [].

However, it has been argued [] that brand legitimacy demonstrates the consistency between the cultural beliefs of brands and consumers. Similarly, as it relates to influencer endorsement, legitimacy reflects the congruence between the influencer’s cultural values and those of their followers. Therefore, it is assumed that the more an influencer represents their followers’ beliefs and values, the greater their cultural fit with the influencer, thus enhancing self-influence congruence. Accordingly, the following hypothesis was proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Influencer legitimacy has a positive impact on self-influencer congruence.

2.3.5. Wishful Identification and Self-Influencer Congruence

Several authors have proposed that identification exists when a person strives to bond with another individual by embracing their behaviors, characteristics, and attitudes or integrating them into their self-concept [,]. Individuals tend to identify with others to receive benefits, such as building interpersonal relationships, improving their self-esteem, or enhancing their capabilities []. Consumers are more likely to adhere to an endorser’s traits, behaviors, and values when they perceive that they share particular beliefs, norms, and interests with the endorser [,]. Identification can be based on actual or perceived similarities or the extent to which a person believes they possess the same attributes as another individual []. On the other hand, identification can also be wishful, signifying a persons’ fascination with being like another individual even if they are not []. Wishful identification is grounded in social cognitive theory, which proposes that individuals transform their behaviors, attitudes, and emotional values to imitate those of another person through psychological matching [].

Self-determination theory states that people tend to gratify their relatedness needs, which illustrates their wish to associate with or be accepted by others []. This is because influencers are regarded as accessible and relatable [] due to their tendency to communicate with their followers directly and refer to them as peers [,]. However, a study by Schouten et al. [] revealed that followers exhibit more wishful identification for influencers than for celebrities. Due to the recent growth in influencer marketing, many people wish to become social influencers [].

Moreover, perceived similarity intensifies the wishful identification of followers as they find it convenient to be like influencers []. Therefore, as wishful identification is based mainly on the principles of similarity with the influencer, it assumes that greater wishful identification strengthens self-influencer congruence. Hence, the following hypothesis was generated:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Followers’ wishful identification with influencers is positively related to self-influencer congruence.

2.3.6. Self-Influencer Congruence and Influencer Recommendations

A recommendation is an individual’s tendency to spread positive WOM regarding a product or service after experiencing it []. When consumers are loyal to a company or satisfied with its products or services, they are more likely to act as ambassadors for that brand by recommending it to other customers [].

Similarly, when consumers identify with a brand, they are more likely to advocate it [,]. This advocacy is carried out both physically and socially. The former involves purchasing and using the brand’s products to feel connected, whereas the latter involves recommending the brand to others []. Previous research [] also suggests that a consumer’s identification with a brand influences their extra-role behaviors (in the form of recommendations).

Similarly, studies on places and tourism have revealed that when individuals demonstrate congruity with specific destinations, they exhibit positive behavioral outcomes (e.g., recommendations and positive WOM) [,]. In the context of influencer marketing, followers are likely to recommend the products or services endorsed by influencers who they like and feel congruent with. Based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis was developed:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Self-influencer congruence makes consumers more likely to recommend products or services endorsed by influencers.

2.3.7. Self-Influencer Unity and Desire to Mimic

The literature indicates that humans tend to mimic people with whom they interact in various ways [,]. Research in the field of neuroscience links mimicry with the stimulation of mirror neurons that participate in behavioral and perceptional mechanisms [], leading to the mimicry of postures [], emotions [], and behaviors related to consumption []. According to these studies, mimicry is an inevitable and subconscious behavior []. Nevertheless, the mimicry of consumption behaviors is mostly intentional, as consumers are driven by the need to look, feel, or act like others. In the context of the consumer doppelganger effect, consumers decide who they wish to mimic; what behaviors, activities, or products they will imitate, and how long the mimicry will last []. Hence, mimicry does not appear to be an automatic reaction but a planned process carried out to fulfill one’s goals.

Social learning theory also explains the significance of modeling or mimicking others’ behaviors in the context of consumption []. This theory suggests that individuals alter their behaviors by modeling or imitating others’ actions, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors through repetitive learning experiences []. Through these experiences, individuals meet several people in their social environment who can impact their behavior.

The literature [,,] indicates that individuals regard these people as role models. Research has also revealed that people tend to mimic the actions of both direct role models (e.g., family, friends, and peers) and indirect role models (e.g., TV stars, athletes, and other celebrities). Research on role models indicates that individuals imitate the behaviors of those they regard as relevant or congruent with themselves in terms of their physical appearance, interests, and abilities [,,].

Several studies have explored the impact of celebrities as role models, and who individuals imitate due to their relevance. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has analyzed the effect of self-congruence with social media influencers on consumers’ desire to mimic. In light of this, and based on the above discussion, the following hypothesis was developed:

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Self-influencer congruence is positively related to consumers’ desire to mimic.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

An online survey was conducted among social media influencers to test our hypotheses. In a pre-test, only 18 of 73 influencers were selected. The influencers were selected based on how many followers they have (i.e., more than 100,000). Influencers who are more popular among a large number of followers were chosen because they are easier to reach with regard to their followers compared to influencers with relatively few followers. Hence, responses from influencers who did not fit the criterion were excluded from the analysis to enhance the accuracy of the results according to the framework proposed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

The data regarding the selected influencers were collected via a close-ended questionnaire. The questions were written in English, and the questionnaire had three parts. The first part presented an overview of the study; the second part collected respondents’ demographic data, and the third part asked questions related to the pre-defined variables.

Respondents were ensured that their information would remain secure and that the results would be presented collectively. The data were collected three to four months earlier to analyze the existing situation. They were required to choose the influencers (beauticians and vloggers) that they followed from the list provided. A total of 750 survey links were distributed through WhatsApp, email, and Facebook. In total, 602 responses were received, of which 451 were valid, which translates to a response rate of 60%.

3.2. Measures

All variables except brand recommendation were measured using pre-defined validated scales. The researcher used a 5-point Likert scale on which responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The self-esteem motive was measured using Rosenberg’s (1965) 10-item scale. The scale for the affiliation motive was adapted from [], while wishful identification was measured based on four items adapted from []. Influencer nostalgia and influencer legitimacy were measured by adjusting the items used by []. Four items of self-influence were previously used by [], whereas the desire to mimic was measured by adapting items from []. No suitable scale for brand recommendation was available in the literature. Hence, previous researchers’ steps [,] were followed to develop an influencer recommendation scale, which was further adapted for influencer recommendation.

3.2.1. Scale Development Process: Brand Recommendation

Scale development techniques suggested in the literature [,] were used in the present study to develop a brand recommendation scale. The scale development process followed in this study is comprised of four stages: item generation, scale purification, scale validation, and nomological validity.

Phase 1: Item Generation

This first step in the scale development process involves generating the scale’s items, either through a deductive or inductive approach []. In this study, the deductive approach was used, as it offered a clear understanding of the construct under consideration through a detailed literature review. Through the review, the construct’s domain was determined by deciding which elements should be included or excluded from the definition, thereby generating relevant items.

The term “recommendation” refers to an individual’s tendency to engage in positive WOM regarding a product or service after experiencing it []. When consumers are loyal to a company or are satisfied with its products or services, they are more likely to act as ambassadors of that brand to other customers []. In influencer marketing, followers are likely to recommend products or services endorsed by influencers that they follow. Previous researchers have conceptualized recommendations through different dimensions. For instance, the authors of [] discuss recommendations in the context of WOM. The researchers [] stated that when a customer participates in brand-related communities, they are likely to develop a strong membership with the brand, leading to recommendation intentions towards those communities. Similarly, Tuškej et al. [] considered positive WOM as an outcome of consumers’ identification with a brand and suggested that brand identification increases consumers’ commitment to a brand, leading to positive WOM.

Similarly, Rialti et al. [] measured consumers’ likelihood to recommend a brand online through positive electronic WOM (i.e., recommending a company to friends and acquaintances on online platforms). The authors of [] also evaluated recommendations made through positive WOM. On the other hand, several studies [,,] conceptualized brand recommendations through “recommendation intention” (i.e., a customer’s intention to recommend a brand or product to others).

However, preferences do not always predict actual behaviors []. Hence, researchers need to evaluate consumers’ actual behavioral outcomes. Another study [] conceptualized brand recommendation as “brand advocacy” and suggested another approach to measure recommendation. The authors stated that consumers make recommendations because of social advocacy, which results from their identification with a brand. A list of items taken from recent studies on recommendations is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Previous studies on recommendation.

Phase 2: Scale Purification

The preliminary set of items was analyzed for clarity and relevance and then presented to six subject experts, including marketing researchers and professors. The experts were given the conceptual definitions of the construct and asked to identify which items fit the definition of brand recommendation. The experts rated each of them as “clearly representative,” “moderately representative,” and “not representative.” The items were also modified and adjusted according to our construct (i.e., brand recommendation); items that did not represent the construct were removed. As a result, 15 items were eliminated from the initial set, leaving only seven for further procedures.

The pre-test was a pilot study with 70 consumers to evaluate the measurement items’ Exploratory Factor Analysis and reliability to refine the finalized items. Of the 70 product consumers, 54.3% were males, 82.9% were aged 26–30 years, and 54.3% were students (with 45.7% possessing a degree). Regarding service consumers, 51.4% were males, 80% were 20–30 years old, and 42.9% were students (with 51.4% having a Masters’ degree).

Explanatory factor analysis was used to observe the factor structures of the items or variables. A correlation matrix with reproduced extraction results was obtained by using the maximum likelihood and Promax methods; all values less than 0.4 were suppressed. These were again processed in SPSS. This time, the results showed a Kaiser–Meter–Olkin value of 0.933. All the values for the initial and extraction communalities were more than 0.6, and the overall factor loading of each item was greater than 0.8. Later, the statistical approval for internal consistency was checked among the seven constructs of the proposed scale, which achieved a value of 0.945.

Phase 3: Scale Validation

The third phase is scale validation, in which the proposed scale was verified for a brand recommendation. The suggested items had been previously studied [,], proposed, operationalized, and validated. A questionnaire with seven items representing brand recommendations was distributed (Appendix A). Data were collected from social media users; 271 responses were considered after removing outliers and questionnaires with missing responses.

The convergent validity among the variable items was verified following []. The convergent validity values of all items were within the acceptable range. Convergent validity was evaluated using the two standards mentioned in the literature earlier: factor loading and average variance extracted (AVE); both the values should be greater than 0.5 [].

Phase 4: Nomological Validity

Ensuring nomological validity involves investigating the newly proposed items of a variable and their alignment with the existing literature to check the items’ validity and reliability with other variables [,,]. To establish nonlogical validity, we tested the relationships among all the proposed conceptual framework variables and influencer recommendation variables.

4. Results

4.1. Demographics of Respondents

We distributed 750 questionnaires through WhatsApp, emails, and Facebook, of which 602 were received; of these, 451 were deemed acceptable for data analysis after screening. The respondents for the study comprised 159 males (35.3%) and 292 (64.7%). Of the primary study respondents, the largest age group was 19–24 years old (42.4%). Also, 26.9% of respondents held a Master’s degree. Respondents were characterized based on the average time they spend using social media—the largest group in this regard spent three to four hours per day using social media (35.5%) as mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographics of respondents.

4.2. Reliability and Validity

Reliability was observed through two methods: Cronbach alpha and composite reliability. For both reliabilities, all the values were within the acceptable range of 0.7 to 0.9 []. Confirmatory factor analysis is the most often-used tool for observing the validity. The results of the measurement model were CMIN/DF = 1.87. The following absolute fit indexes were also measured: RMSEA = 0.044, GFI = 0.901, and AGFI = 0.881. Incremental fit measures were also estimated as follows: CFI = 0.901 and NFI = 0.938. All of these values fall within the acceptable range indicated by the literature [].

Convergent and discriminant validity were determined using confirmatory factor analysis as recommended in [,]. Convergent validity was evaluated based on two standards mentioned in the literature—factor loading and AVE—both of which should be greater than 0.5 []. The convergent validity and discriminant validity of the measurement model were also analyzed. Convergent validity was assessed through factor loading, composite validity (CR), and AVE []. Table 3 shows that the factor loading value exceeds the threshold of 0.5 []. The CR and AVE values of the conceptual model also exceeded the acceptable thresholds of 0.7 and 0.5, respectively [].

Table 3.

Convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was evaluated based on two conditions. First, the correlation between the conceptual model variables needed to be less than 0.85 []. Secondly, the AVE’s square value must be less than the conceptual model’s value []. Furthermore, the measurement model evaluated discriminant validity. The square root of AVE, which is related to discriminant validity, should be greater than the construct correlations as mentioned in Table 4.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

4.3. Hypotheses Testing

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to test the proposed hypotheses, as suggested in []. The researcher adopted maximum likelihood estimate techniques, while SEM lessened the lack of normality because it overcomes all normality violations. Power analysis is a critical factor in SEM, especially regarding the estimation of power due to error variance, covariance, and the estimation method, as suggested in []. Jana et al. [] stated that the sample size should be around 150–200 to ensure adequate power. For this purpose, the researchers used a large sample size to minimize difficulties associated with a small sample size.

SEM techniques were incorporated to analyze the hypotheses proposed for the conceptual framework. The structural model indicated good model fit indices (i.e., CMIN/dF = 1.79, RMSEA = 0.037, GFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.971, TLI = 0.966, NFI = 0.937, IFI = 0.971). All the proposed hypotheses were accepted for the presented framework as mentioned in Table 5.

Table 5.

Hypotheses testing.

Consumers’ self-esteem and affiliation motives strengthen the impact of self-influencer congruence. Consumers prefer influencers who they feel they are similar to, thus supporting H1 and H2. Regarding the other hypotheses, high levels of influencer nostalgia, legitimacy, and wishful identification among consumers are linked to common beliefs and other similarities between consumers and influencers. Thus, the results support H3, as consumers recommend influencers to others, especially friends and family members, which indicates a positive relationship between influencer recommendations and the desire to mimic consumer behavior.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contribution

The findings contribute significantly to the literature by addressing self-influencer congruence, specifically in terms of consumer consumption and influencer recommendations. This study’s findings confirm the impact of consumers’ self-concept motives (affiliation and self-esteem motives) and influencer affinity (nostalgia, legitimacy, and wishful identification) on self-influence congruence, the tendency to make recommendations, and the desire to mimic influencers.

The results also show that consumers’ desires and needs are essential in the context of product or service consumption. These results corroborate the findings of previous studies [,]. The study shows that consumers’ self-congruence can be increased through links with cultural values, beliefs, and symbols, thereby enhancing endorsement efficiency []. Thus, this study’s main contribution is the identification of a significant relationship between influencer affinity in terms of nostalgia, legitimacy, wishful identification, and self-influencer congruence.

5.1.1. Self-Concept Motives

Self-concept can be expressed as the aggregate feelings and perceptions an individual has about himself or herself []. The research explored the influence of famous influencers through social media on their followers in terms of consumption. The first and second hypotheses suggested relationships between consumers’ self-concept motives, affiliation, self-esteem motives, and self-influence congruence. Thus, this study aligns with the existing literature [,] that shows that consumers are more indulgent when shopping for products or services to which they feel connected. Moreover, purchasing such products or services enhances their self-esteem and association with congruence [].

5.1.2. Influencer Affinity

The present study further explored the impact of the influencer affinity in terms of nostalgia, legitimacy, and wishful identification as they relate to self-influencer congruence. The results indicated positive relationships for these factors. Thus, the results reveal consumers’ and influencers’ practical attitudes towards products and services. The rise of social media platforms has led consumers to form positive attitudes towards influencers who they perceive as having similar beliefs. The support for this study’s hypotheses aligns with earlier studies [,] showing that consumers tend to associate with influencers who they feel think the same way as them.

5.1.3. Influencer Recommendations

Finally, the present research explored the relationships between self-influence congruence and influencer recommendations, and the desire to mimic consumers. The results reveal that consumers who feel an association with influencers tend to recommend them to family and friends. This finding aligns with previous studies [,] that state that the greater the degree of association consumers feel with an influencer, the higher the degree of self-congruence. Customers who are satisfied with a product or service tend to act as ambassadors by suggesting it to others. Furthermore, influencers are famous for having similar attitudes and beliefs as their followers, and these followers desire to mimic these influencers in various ways, including their consumption behaviors.

6. Conclusions

Regarding self-concept motives, affiliation, and self-esteem motives, social media plays a significant role in creating and establishing connections between people, especially between followers and the influencers who inspire them. Moreover, these concepts enhance congruence, along with consumers’ self-esteem, as discussed in the earlier literature [,].

Moreover, influencer affinity (specifically in regard to nostalgia, legitimacy, and wishful identification) enhances self-influencer congruence. Thus, it appears that consumers and influencers have practical attitudes towards products and services. Furthermore, social media platforms enable consumers to form positive attitudes towards influencers with whom they feel they share beliefs. A consumer’s affiliation and self-esteem motives lead them to purchase brands or products that align with their self-concept.

Self-influencer congruence leads consumers to mimic influencers who they admire. For that reason, consumers pay special attention to the recommendations of influencers that they consider as their role models.

This study fills a gap in the literature regarding self-influencer congruence, showing that it persuades consumers to purchase products or services that they feel associated with. The existing literature [] also suggests that consumers’ association with influencers is based on shared perspectives and beliefs. Thus, the study contributes to the literature by indicating positive relationships between self-influencer congruence, the degree of recommendation, and the desire to mimic.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

Even though this research revealed significant results, it has some limitations. First, the study analyzed only a few factors that affect self-influencer congruence. Future studies should examine other motives that might impact self-influencer congruence. Second, this study was cross-sectional in terms of data collection, which tends to differentiate the results. In the future, participants could be assessed after some time has passed to generate more accurate findings. Future research could also be conducted in specific fields (e.g., tourism, hospitality). Furthermore, future studies could apply control variables (e.g., age, gender) to check their influence on the proposed model.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.X., Formal analysis, L.X., Validation, L.X., Investigation, A.S., Writing—original draft, A.S., Conceptualization, S.M.T., Writing—original draft, A.S., Visualization J.U.H., Supervision, J.U.H., Writing—review & editing, J.U.H., Validation, M.G. and Visualization M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Scale of Influencer Recommendation (New Scale).

Table A1.

Scale of Influencer Recommendation (New Scale).

| IR1 | I always recommend this influencer’s recommendation to my friends and acquaintances. |

| IR2 | I always recommend this influencer’s suggestions to people seeking advice over social media. |

| IR3 | I spread positive words regarding the influencer recommendation in my community. |

| IR4 | I always speak in favor of this influencer’s recommendation. |

| IR5 | I always spread the good news about the influencer recommendation. |

| IR6 | I tend to share my personal experience with this influencer suggestions. |

| IR7 | I do not miss any chance to say good things about this influencer suggestions. |

References

- Kaplan, A.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! the challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J.H.; Hermkens, K.; McCarthy, I.P.; Silvestre, B.S. Social media? Get serious! Understanding the functional building blocks of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2011, 54, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ki, C.W.C.; Kim, Y.K. The mechanism by which social media influencers persuade consumers: The role of consumers’ desire to mimic. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 36, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, C.C.; Lemon, L.L.; Hoy, M.G. # Sponsored# Ad: Agency perspective on influencer marketing campaigns. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2019, 40, 258–274. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audrezet, A.; De Kerviler, G.; Moulard, J. Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 117, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, C.; Cuevas, L.; Chong, S.; Lim, H. Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Souiden, N.; Ladhari, I. Determinants of loyalty and recommendation: The role of perceived service quality, emotional satisfaction and image. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2011, 16, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre-Rodriguez, A.; Bosnjak, M.; Sirg, M. Moderators of the self-congruity effect on consumer decision-making: A meta-analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorn, R.J.; Veen G v Rompay, T.J.; Hegner, S.M.; Pruyn, A.T. Human values as added value(s) in consumer brand congruence: A comparison with traits and functional requirements. J. Brand Manag. 2020, 28, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boksberger, P.; Dolnicar, S.; Laesser, C.; Randle, M. Self-congruity theory: To what extent does it hold in tourism? J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choi, S.M.; Rifon, N.J. It is a match: The impact of congruence between celebrity image and consumer ideal self on endorsement effectiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2012, 29, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y.; Riley, M. An investigation of self-concept: Actual and ideal self-congruence compared in the context of service evaluation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2003, 10, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kressmann, F.; Sirgy, M.J.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F.; Huber, S.; Lee, D.-J. Direct and indirect effects of self-image congruence on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Influencer Marketing Hub. Influencer Marketing Stats|80 Influencer Marketing Statistics for 2020. 2020. Available online: https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-statistics/ (accessed on 16 April 2020).

- Magno, F.; Cassia, F. The impact of social media influencers in tourism. Anatolia 2018, 29, 288–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Chen, K.J.; Lin, J.S. When social media influencers endorse brands: The effects of self-influencer congruence, parasocial identification, and perceived endorser motive. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 590–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Rabbanee, F.K. Antecedents and consequences of self-congruity. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimp, T.A. Advertising, Promotion and Supplemental Aspects of Integrated Marketing Communications, 6th ed.; South Western Cengage Learning: Mason, IO, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Teng, L.; Foti, L.; Yuan, Y. Using self-congruence theory to explain the interaction effects of brand type and celebrity type on consumer attitude formation. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 103, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvio, A.; Gavish, Y.; Shoham, A. Consumer’s doppelganger: A role model perspective on intentional consumer mimicry: Consumer’s doppelganger. J. Consum. Behav. 2013, 12, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipanagiotou, K.; Christodoulides, G.; Veloutsou, C. Managing the consumer-based brand equity process: A cross-cultural perspective. Int. Bus. Rev. 2019, 28, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rialti, R.; Zollo, L.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Ciappei, C. Exploring the Antecedents of Brand Loyalty and Electronic Word of Mouth in Social-Media-Based Brand Communities: Do Gender Differences Matter? J. Glob. Mark. 2017, 30, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altunel, M.C.; Erkurt, B. Cultural tourism in Istanbul: The mediation effect of tourist experience and satisfaction on the relationship between involvement and recommendation intention. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, W.M.; Hyatt, C. I despise them! I detest them! Franchise relocation and the expanded model of organizational identification. J. Sport Manag. 2007, 21, 194–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J. Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basil, M.D. Identification as a mediator of celebrity effects. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 1996, 40, 478–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usakli, A.; Baloglu, S. Brand personality of tourist destinations: An application of self-congruity theory. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pratt, S. Social media influencers as endorsers to promote travel destinations: An application of self-congruence theory to the Chinese Generation Y. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 958–972. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Johar, J.S.; Samli, A.C.; Claiborne, C.B. Self-congruity versus functional congruity: Predictors of consumer behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1991, 19, 363e375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Grace, B.Y. Revisiting self-congruity theory in consumer behaviour: Making sense of the research so far. In Routledge International Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Routledge: England, UK, 2016; pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Kuenzel, S.; Halliday, S.V. The chain of effects from reputation and brand personality congruence to brand loyalty: The role of brand identification. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2010, 18, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, S.D.; Lomore, C.D. Admirer-celebrity relationships among young adults: Explaining perceptions of celebrity influence on identity. Hum. Commun. Res. 2001, 27, 432–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. You are what they eat: The influence of reference groups on consumers’ connections to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. Connecting with Celebrities: Celebrity Endorsement, Brand Meaning, and Self-Brand Connections. 2008. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Connecting-with-Celebrities-%3A-Celebrity-Endorsement-Escalas-Bettman/34040edbee8596767c832e4816b6ed3a73b12905 (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, M.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehm, S.S.; Kassin, S.M.; Fein, S. Social Psychology; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.N. Personality Research form Manual; Research Psychologists Press: Port Huron, MI, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bento, M.; Martinez, L.M.; Martinez, L.F. Brand engagement and search for brands on social media: Comparing Generations X and Y in Portugal. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In Social Comparison Theories: Key Readings in Social Psychology; Stapel, D.A., Blanton, H., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N.; Smollan, D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.M.; Perse, E.M.; Powell, R.A. Loneliness, Parasocial Interaction, and Local Television News Viewing. Hum. Commun. Res. 1985, 12, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietkiewicz, K.J.; Dorsch, I.; Scheibe, K.; Zimmer, F.; Stock, W.G. Dreaming of stardom and money: Micro-celebrities and influencers on live streaming services. In International Conference on Social Computing and Social Media; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 240–253. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.B.; Yeh, S.S.; Huan, T.C. Nostalgic emotion, experiential value, brand image, and consumption intentions of customers of nostalgic-themed restaurants. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveland, K.E.; Smeesters, D.; Mandel, N. Still preoccupied with 1995: The need to belong and preference for nostalgic products. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehling, D.D.; Sprott, D.E.; Sultan, A.J. Exploring the Boundaries of Nostalgic Advertising Effects: A Consideration of Childhood Brand Exposure and Attachment on Consumers’ Responses to Nostalgia-Themed Advertisements. J. Advert. 2014, 43, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. In search of authenticity. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 1083–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.B.; Merchant, A.; Bartier, A.-L.; Friedman, M. The cross-cultural scale development process: The case of brand-evoked nostalgia in Belgium and the United States. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 83, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, V.J.; Sprott, D.E.; Muehling, D.D. The influence of evoked nostalgia on consumers’ responses to advertising: An exploratory study. J. Curr. Issues Res. Advert. 2002, 24, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisenwitz, T.H.; Iyer, R.; Cutler, B. Nostalgia Advertising and the Influence of Nostalgia Proneness. Mark. Manag. J. 2004, 14, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitektine, A.; Haack, P. The “macro” and the “micro” of legitimacy: Toward a multilevel theory of the legitimacy process. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, S.M. The dynamics of brand legitimacy: An interpretive study in the gay men’s community. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, K.; Schoenmueller, V.; Bruhn, M. Authenticity in branding–exploring antecedents and consequences of brand authenticity. Eur. J. Mark. 2017, 51, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.H. Burkeian and Freudian theories of identification. Commun. Q. 1994, 42, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffner, C.; Buchanan, M. Young Adults’ Wishful Identification With Television Characters: The Role of Perceived Similarity and Character Attributes. Media Psychol. 2005, 7, 325–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.E.; Cialdini, R.B.; Aiken, L.S. Social norms and health behavior. In Handbook of Behavioral Medicine; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, H.C. Interests, relationships, identities: Three central issues for individuals and groups in negotiating their social environment. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schouten, A.P.; Janssen, L.; Verspaget, M. Celebrity vs. Influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and Product-Endorser fit. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, M.R. The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the credibility of online celebrities’ Instagram profiles in influencing the purchase decisions of young female users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erz, A.; Christensen AB, H. Transforming consumers into brands: Tracing transformation processes of the practice of blogging. J. Interact. Mark. 2018, 43, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, V.; Prothero, A. Beauty bloggers and YouTubers as a community of practice. J. Mark. Manag. 2018, 34, 592–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, H.S. A study of influencer marketing strategy in cosmetics industry. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Konyang University, Daejeon, Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rambocas, M.; Kirpalani, V.M.; Simms, E. Brand equity and customer behavioral intentions: A mediated moderated model. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 36, 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokburger-Sauer, N.; Ratneshwar, S.; Sen, S. Drivers of consumer–brand identification. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahearne, M.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Gruen, T. Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kemp, E.; Childers, C.Y.; Williams, K.H. Place branding: Creating self-brand connections and brand advocacy. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2012, 21, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartrand, T.L.; Bargh, J.A. The chameleon effect: The perception behavior link and social interaction. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, R.J.; Ferraro, R.; Chartrand, T.L.; Bettman, J.; van Baaren, R. Of chameleons and consumption: The impact of mimicry on choice and preferences. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 34, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacoboni, M.; Woods, R.P.; Brass, M.; Bekkering, H.; Mazziotta, J.C.; Rizzolatti, G. Cortical mechanisms of human imitatio. Science 1999, 286, 2526–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hatfield, E.; Cacioppo, J.T.; Rapson, R.L. Emotional Contagion; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, W.; Paul, A.; Martin, C.; Bush, A.J. The effect of role model influence on adolescents’ materialism and marketplace knowledge. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, P.; Kunda, Z. Superstars and me: Predicting the impact of role models on the self. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.A.; Bush, A.J. Do role models influence teenagers’ purchase intentions and behavior? J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesser, A. Some effects of self-evaluation maintenance on cognition and action. In The Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior; Sorrentino, R.M., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 435–464. [Google Scholar]

- Stokburger-Sauer, N.E.; Hoyer, W.D. Consumer advisors! revisited: What drives those with market mavenism and opinion leadership tendencies and why? J. Consum. Behav. 2009, 8, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enginkaya, E.; Yılmaz, H. What drives consumers to interact with brands through social media? A motivation scale development study. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 148, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Suryani, S.D.; Amin, M.; Rohman, F. The Influence of the Research-based Monograph Book to Improve Pre-Service Teachers’ Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior. J. Pendidik. IPA Indones. 2021, 10, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshneya, G.; Das, G. Experiential value: Multi-item scale development and validation. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woisetschläger, D.M.; Hartleb, V.; Blut, M. How to Make Brand Communities Work: Antecedents and Consequences of Consumer Participation. J. Relatsh. Mark. 2008, 7, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuškej, U.; Golob, U.; Podnar, K. The role of consumer–brand identification in building brand relationships. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R.; Massa, E.; Skandrani, H. YouTube vloggers’ popularity and influence: The roles of homophily, emotional attachment, and expertise. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 54, 102–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhou, Z.; Zhan, G.; Zhou, N. The impact of destination brand authenticity and destination brand self-congruence on tourist loyalty: The mediating role of destination brand engagement. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 15, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sook Kwon, E.; Kim, E.; Sung, Y.; Yun Yoo, C. Brand followers: Consumer motivation and attitude towards brand communications on Twitter. Int. J. Advert. 2014, 33, 657–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Celsi, M.; Ortinau, D.J.; Bush, R.P. Essentials of Marketing Research; McGraw-Hill/Irwin: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, B.W.; Khong, K.W. Examining the effects of customer service management (CSM) on perceived business performance via structural equation modelling. Appl. Stoch. Models Bus. Ind. 2006, 22, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, A.; Ghazali, Z.; Albinsson, P.A. Construction and validation of customer value co-creation attitude scale. J. Consum. Mark. 2017, 34, 591–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, E.; Halle, T.; Terry-Humen, E.; Lavelle, B.; Calkins, J. Children’s school readiness in the ECLS-K: Predictions to academic, health, and social outcomes in first grade. Early Child. Res. Q. 2006, 21, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, T. Psychological Testing: A Practical Approach to Design and Evaluation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P. Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, S.; Das, J.R.; Dash, M. Modeling brand personality using structural equation modeling. Int. J. Mark. Technol. 2014, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Lee, D.J.; Johar, J.S.; Tidwell, J. Effect of self-congruity with sponsorship on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, N.; Steinfeld, C.; Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook “Friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2007, 12, 1143–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).