1. Introduction

In the era of big data, the progress of information technology enables firms to collect consumer information with unprecedented speed and capacity, and identify consumers in more and more sophisticated ways [

1]. Firms can analyze consumers’ personal characteristics and preferences by collecting consumers’ information, so as to practice personalized pricing [

2]. For example, cookies, loyalty cards, Wi-Fi, and other automated data collection devices can be used to track consumers’ virtual purchase footprints [

3]. Firms can identify new and old customers, and provide them with different products, services, and prices based on their purchase history data [

4]. Using consumers’ past purchase history to differentiate new and old customers and make price-discrimination is called behavior-based price discrimination (BBPD). This pricing model relies on the collection of consumer information by firms. The more information collected by firms, the more sophisticated pricing can be made for consumers.

In addition to collecting information from old customers, firms can even collect more information about consumers through information sharing. For example, in the grocery store and pharmacy market, Catalina Marketing organizes retailers to share customer purchase history data to help them design promotional activities [

5]. In the aviation industry, Delta claims that it shares consumer information with SkyMiles alliance partners, including Alaska Airlines, Hawaiian Airlines, etc. This enables airlines to track passengers’ flyer statuses together, to better understand their needs. In the retail industry, Lands’ End Inc., which sells clothing online and through catalogues, shares consumer information with competitive firms. WalMart and Target cooperated with other large retailers to develop a mobile payment system called Merchant Customer Transaction (MCX). MCX’s CurrentC supports data collection. These retailers promise to use CurrentC as their exclusive payment system, strictly control customer data, and cooperate effectively [

6]. These examples prove that there are a large number of information sharing practices among firms in reality, which shows that information sharing is helpful for firms to understand consumers, thus making more accurate price discrimination.

However, the information security problem created by the large-scale collection, utilization, and sharing of consumers’ private information by firms will cause consumers privacy concerns. For example, after Cambridge Analytica was found to abuse Facebook user information, Facebook shares fell by 5% [

7]. Acxiom, one of the largest information providers, claims to have the information of more than 200 million Americans. Large technology companies, such as Facebook, Google, and Amazon, collect more than 1 billion discrete units of information from users every month [

8]. The evidence mentioned above indicates that consumers will incur disutility when they purchase from a firm that has obtained their information. Sharing information about consumers among firms will also cause consumers privacy concerns, but this information sharing behavior can alleviate the problem of information asymmetry in the market to some extent, improve the efficiency of resource allocation in the market economy, and promote competition. For example, the banking and insurance markets will exchange the records of customer default and risk characteristics, so as to know the customers with credit default and reduce their risk.

In view of this, should the government regulate on how competing firms collect and share private data of specific users, or should the government promote firms to exercise self-regulating when privacy issues are involved [

9]? With the growing concern for consumers’ privacy, scholars have begun to propose various regulations to protect consumers’ privacy. A large number of related studies focus on increasing consumers’ control over privacy, and restricting firms’ information collection behavior [

1,

10], but few studies consider the information sharing behavior among firms. In addition, most studies try to put forward a powerful privacy protection measure to put consumers in a better position, but many studies point out that privacy protection measures that seem to be beneficial to consumers will actually harm them [

9,

11]. Considering the uncertainty of the benefits of privacy protection measures, this paper, based on the research of Shy and Stenbacka [

9], attempts to explore the impact of different degrees of privacy protection measures on consumers.

In this paper, we study the influence of three different levels of privacy regulation concerning information sharing among firms on each market party. This paper studies the pricing strategies of competing firms under different levels of privacy regulation, and explores what role consumers’ privacy preferences and product preferences play in the competition game. In this study, the level of privacy regulation determines the extent to which firms can use consumers’ private information for differentiated pricing. Specifically, this paper attempts to answer the following questions: (1) considering consumers’ privacy concerns, how do firms charge new and old customers under different levels of privacy regulation? (2) What kind of competitive effect will information sharing cause among firms? (3) What is the relationship between industry profits, consumer surplus, and social welfare under different levels of privacy regulation? (4) Which privacy regulation should the government implement in order to optimize social welfare? In order to solve the above problems, this paper establishes a two-stage duopoly Hotelling competition game model, which applies to the market structure of duopoly, and we consider competition between the duopoly. We discuss the equilibrium results under different levels of privacy regulation, and try to determine which level is more appropriate. The research results not only provide new ideas for scholars to examine the dynamic competition game regarding consumers’ privacy concerns, but also provide some theoretical guidance and suggestions for relevant government agencies to formulate appropriate privacy regulation, and stimulate the market to develop more smoothly and effectively.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the related literature.

Section 3 describes the problem, explains the symbols, and presents the model.

Section 4 shows the equilibrium results of the model under three privacy regulations.

Section 5 analyzes the welfare of all parties in society under different privacy regulation.

Section 6 shows implications for policy and management, and

Section 7 concludes the paper.

Appendix A contains proof of the results.

2. Literature Review

This study is closely related to two streams of literature. The first is economics literature related to BBPD. There is much literature concerning BBPD, and most of these papers examine the impact of BBPD on firms and consumers, based on the horizontal differences of firms. The classic literature on BBPD holds that, if firms can discriminate against prices, it will lead to intense price competition and lower prices, thus bringing positive effects on consumer surplus [

12,

13]. There are some similarities between the results of this paper and the conclusions of the prior studies [

12,

13,

14]. This paper shows that BBPD will lead to more intense price competition to some extent, which is mainly manifested in the price set for old customers in the second stage, while whether there is strong competition in the price set for new customers in the second stage depends on consumers’ product-privacy preference. In addition, BBPD weakens the first price competition of firms. There are other scholars who extend BBPD, such as considering product quality [

4], analyzing BBPD based on vertical differentiation, and so on. In our model, we consider a problem concerning consumer privacy, i.e., considering that the behavior of firms collecting consumer information will cause consumer privacy concerns. Carroni [

14] admitted that firms’ access to consumer information will cause privacy concerns, but academic circles seldom consider the privacy cost of consumers. Therefore, this paper attempts to explore the impact of consumer privacy costs on BBPD.

Second, this paper is related to the literature on information sharing among firms. Most researchers pay attention to the motivation of vertical or horizontal information sharing among firms. The vertical information sharing happens between the upstream Firm and the downstream firm in a supply chain, while horizontal information sharing involves competing parties, such as two retailers. As far as vertical sharing is concerned, most studies on information sharing focus on market demand information [

15,

16,

17]. For example, Jiang et al. [

16] studies information sharing in a distribution channel where the manufacturer possesses better demand-forecast information than the downstream retailer. They show that among the three formats, ex ante, the retailer prefers the no-sharing format, whereas the manufacturer prefers the mandatory-sharing format. With the development of a platform economy, the platform can collect a lot of information about consumers, and decide whether to share such information with sellers on platform [

7]. Liu et al. [

7] show that, when the platform strategy has two potential constraints (privacy constraint and fairness constraint), the platform always has the incentive to share information, which is beneficial to the platform and all sellers. As far as horizontal sharing is concerned, Chen et al. [

18] show that when both firms have the ability to identify consumers, it is a competitive advantage to identify them more accurately. When competitive firms are in the early stages, i.e., their recognition ability is low, sharing consumer information among firms can achieve a win-win situation. Liu and Serfes [

19] extend the research of Chen et al. [

18]: they report that if the customer bases of the two firms are quite different, information sharing will happen. Kim and Choi [

20] build a two-period model with BBPD and information sharing, which reveals that when firms know that their products are substitutes, information sharing enables them to refine their cognition of each consumer’s preferences. Some studies focus on horizontal information sharing behavior among sellers on the platform. For example, Boon et al. [

21] show that information sharing among competing members in the community improves the productivity of the whole community. Chen and Zhu [

22] explore whether information sharing can benefit individual sellers, and how the market effectively encourages sellers to share information. The results show that information sharing significantly improves the business performance of a single seller. In addition, some studies believe that the connection and social interaction between sellers can produce economic value, and investigate how the platform can better support the social interaction between sellers [

23,

24]. However, some scholars reveal that there is a negative correlation between sellers’ mutual assistance and performance [

25,

26], which is consistent with the results of this study. This study focuses on horizontal information sharing among firms, and shows that when firms are allowed to share information, the profit of firms is the lowest while the consumer surplus is the highest.

There are also papers that consider the interaction between information sharing and market competition. Chen et al. [

18] show that when targetability in a market reaches a very high level, it will intensify the price competition and lead to a prisoner’s dilemma. Liu et al. [

7] and Shy and Stenbacka [

27] also believe that information sharing may intensify competition, and lead to other undesirable results. However, Nijs [

5] believes that information sharing has an anti-competitive effect, and the anti-competitive effect of information exchange may occur even before the exchange itself occurs. This is because forward-looking firms that expect information exchange to generate extra profits will raise prices. The results of this study show that information sharing among firms will intensify competition to a certain extent, and make firms set lower prices for new customers in two periods.

Finally, our paper is also related to literature on privacy regulation. Scholars put forward many privacy regulations methods, and study their influence on competition and social welfare. They focus either on how to improve consumers’ control over privacy [

1,

28], or on how to restrain firms from collecting information [

10]. However, scholars have not reached a consensus on whether privacy regulation is beneficial to consumers. Conti et al. [

10] investigate an opt-in regime of privacy regulation, which requires firms to obtain the consent of consumers before collecting information, and how to affect product quality and consumer surplus. The results reveal that when the complementarity between information and quality is strong, the product quality is higher under the opt-in regime, so consumers are in a better situation. Therefore, they believe that privacy regulation is beneficial to consumers to a certain extent. However, Stigler [

29] states that privacy protection may cause inefficiency, and the government’s policy of protecting consumers’ privacy may not improve welfare. Li et al. [

30] show how the transparency of BBPD affects firms and consumers. He states that the transparency of BBPD leads to price increases, which is good for the company, but harms consumers and society. This result means that forcing firms to disclose their BBPD model to the public is originally intended to protect consumers’ privacy and welfare, but it turns out that it is even worse for consumers. This study has something in common with the above literature, i.e., under the stronger privacy regulation, the welfare of consumers and society may not be better. In addition, some studies on privacy regulation have noticed that consumers’ information may be shared among firms, so they also try to restrain the information sharing behavior among firms. For example, Shy and Stenbacka [

9] evaluate the impact of different degrees of privacy regulation concerning information sharing among firms on corporate profits, consumer surplus, and social welfare in a static environment. They report that when firms are under the weak regulation, i.e., they can collect consumer information but cannot share it with each other, the profits of firms are higher than those under the strong regulation and no regulation, and the consumer surplus and total welfare will always increase with the strengthening of privacy protection. Based on this research, this paper considers the privacy cost of consumers in a dynamic environment, and draws a different conclusion.

In summary, it can be found that there are many studies on firms collecting consumer information for pricing, but the pricing problem involving horizontal information sharing among firms is still relatively limited, and there are mainly the following limitations: first, the research on BBPD is relatively mature, but these studies do not consider the privacy concerns of consumers. The pricing model of firms using consumer-specific information will bring privacy concerns to consumers, and the behavior of information sharing among firms will also cause privacy concerns of consumers, but many models do not consider the privacy cost of consumers. Secondly, most scholars pay attention to sharing market demand information among vertical firms, but few studies focus on sharing consumer information among horizontal firms. Finally, since consumers are paying more and more attention to information security, scholars have put forward various privacy regulations to protect consumers, but most of these studies involve improving consumers’ privacy control and how to restrain firms from collecting consumer information. Very little literature discusses whether to restrict information sharing among firms. In view of this, this paper, based on the research of Shy and Stenbacka [

9], considers the privacy cost of consumers, constructs a privacy regulation regarding firms collecting and sharing consumer information, and tries to explore how this privacy regulation affects the two-stage product price game of competing firms based on consumer purchase history. This paper mainly analyzes the equilibrium results of competing firms under different intensity of privacy regulation, including industry profit, consumer surplus, and social welfare. This study has certain reference significance for relevant government personnel to formulate appropriate privacy regulation to guide the effective operation of the market. In addition, from the consumer’s point of view, consumers can understand the formulation process of firm-related strategies, so as to make rational consumption decisions.

3. The Model

3.1. Problem Description

This paper assumes that there is privacy regulation involving firm information sharing, and the intensity of regulation is divided into three levels. Strong regulation (S) means that firms are not allowed to collect consumer information; medium regulation (M) means that firms are allowed to collect consumer information, but are not allowed to share it with each other; and weak regulation (W) means that firms allow the collecting and sharing of consumer information. By constructing the Hotelling model of duopoly’s two-stage price competition, this paper analyzes the influence of three privacy regulations on industry profit, consumer surplus and social welfare.

3.2. Notation Description

Table 1 summarizes all notations in our models.

3.3. Model Building

We model a duopoly setting, in which two competing firms, A and B, produce the same product or offer the same service in the market. However, the products or services they offer have different features, and this paper uses the Hotelling model to define the product differences between the firms. In the Hotelling model, these two firms are located at both ends of a linear city, with the assumption that, at the end of the interval [0, 1], the distance between them denotes their difference. At the same time, the number of consumers in the market is normalized to one, which is evenly distributed in linear cities. The location of consumers represents their preference for products, and the closer they are to a certain firm, the more they prefer the firm’s products. Therefore, consumers will buy the products closest to themselves. If consumers cannot buy products which are exactly the same as their own preferences, they will face a cost. This disutility is associated to the distance between consumers and firms, and it is produced by each unit distance as . Therefore, represents the product preference of consumer. All consumers have a retention value on products, and will equal zero when they do not buy any products. It is assumed that each consumer only buys a single-unit product in each period, and is large enough to make sure the market fully is covered in each period.

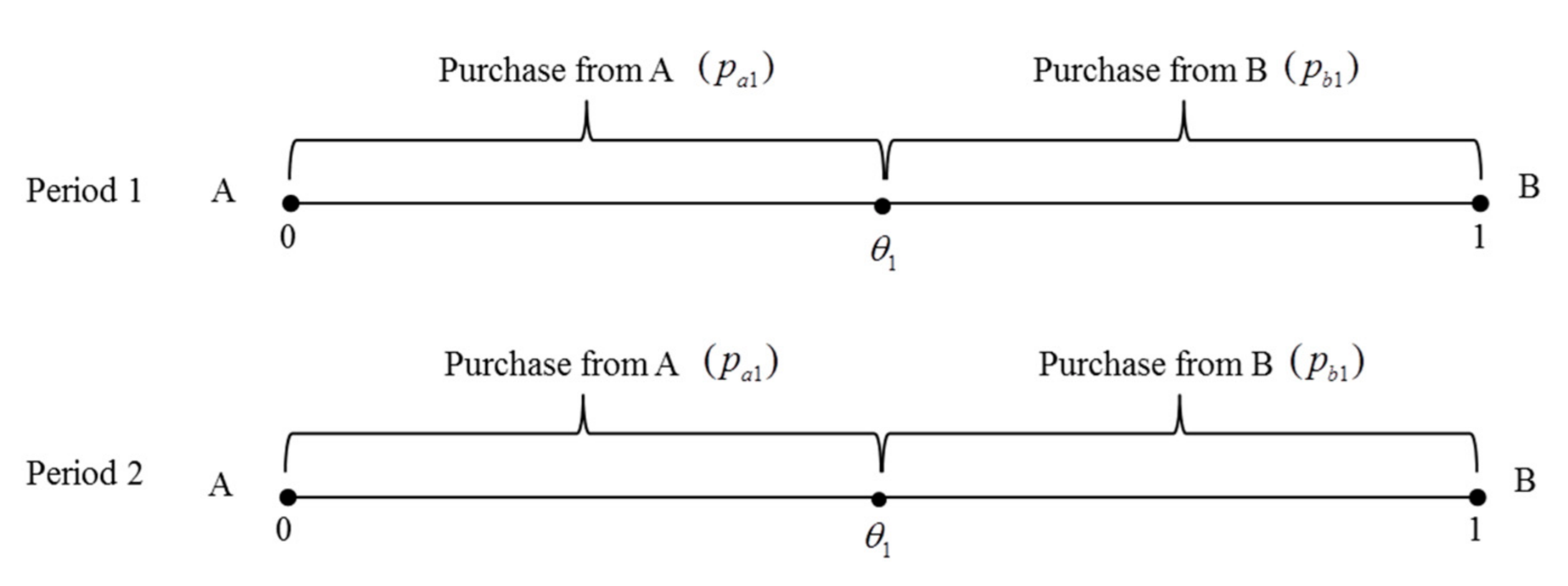

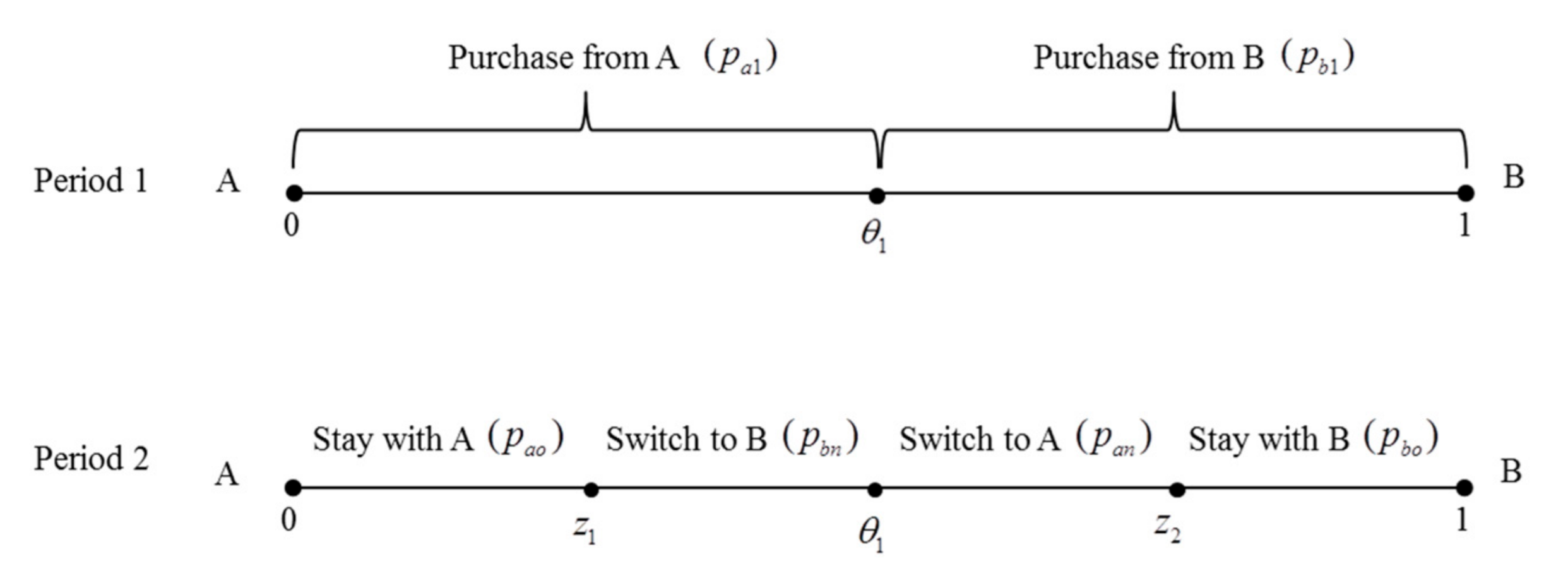

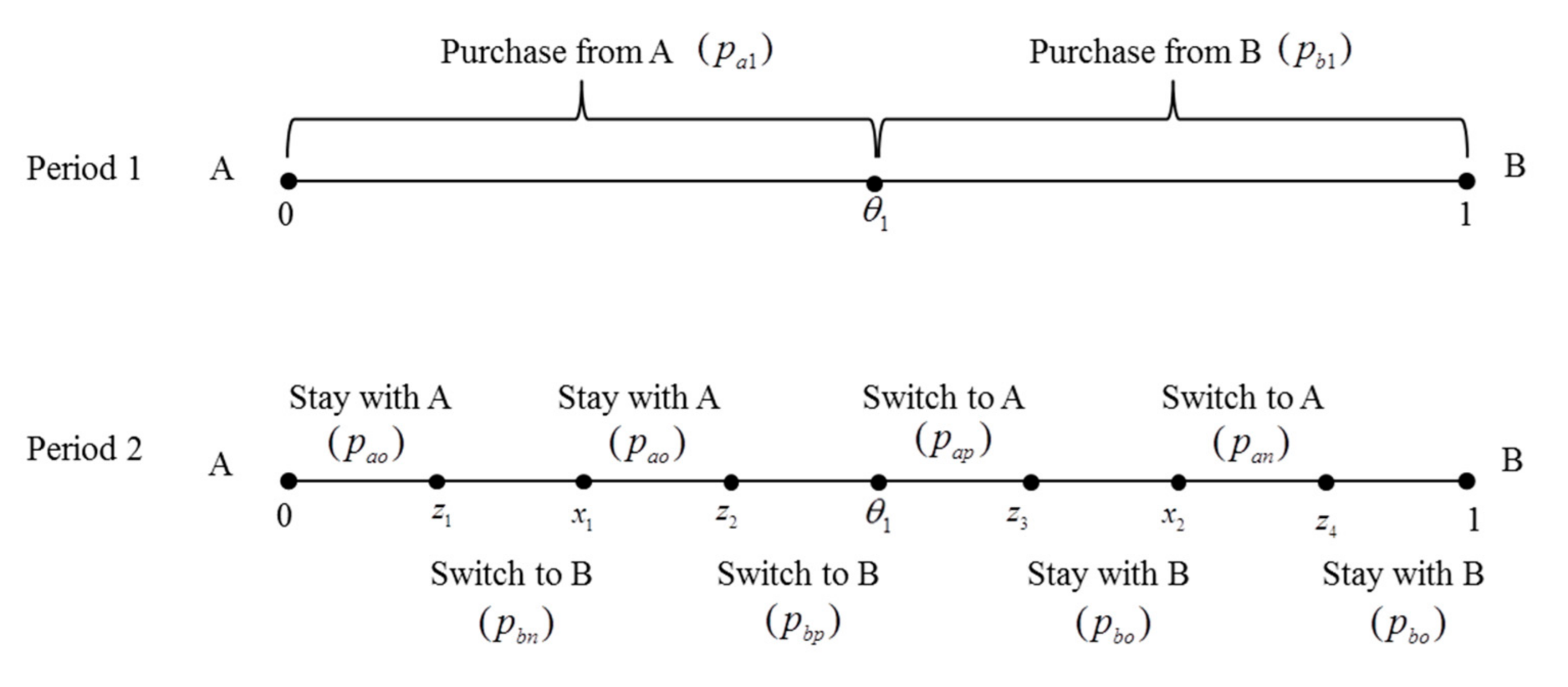

The two-period game unfolds as follows: in the first stage, all consumers are new to the firm, and both firms know nothing about them, so only uniform prices can be offered. After the end of the first period, the two firms can collect the purchase history of consumers, and distinguish between new and old customers under the M and W regulation. After entering the second period, under the S regulation, the situation is the same as that in the first period, i.e., the firms know nothing about consumers, hence the uniform prices are formulated. While under the M and W regulation, firms can identify consumers’ features according to consumers’ information they leave in the first period, and then recommend products that meet consumers’ preferences and set personalized prices. Under the M regulation, two firms only know the preferences of old customers, and formulate two kinds of prices, respectively, for their new and old customers, i.e., . Under the W regulation, two firms can share information about consumers. For consumers whose information is shared, firms can recommend products that meet their preferences, and set poaching prices, i.e., , while for consumers whose information is not shared, firms can only set a uniform new customer price. Similarly, firms will set a personalized price for their old customers. Therefore, there are three types of prices the firms need to formulate, i.e., .

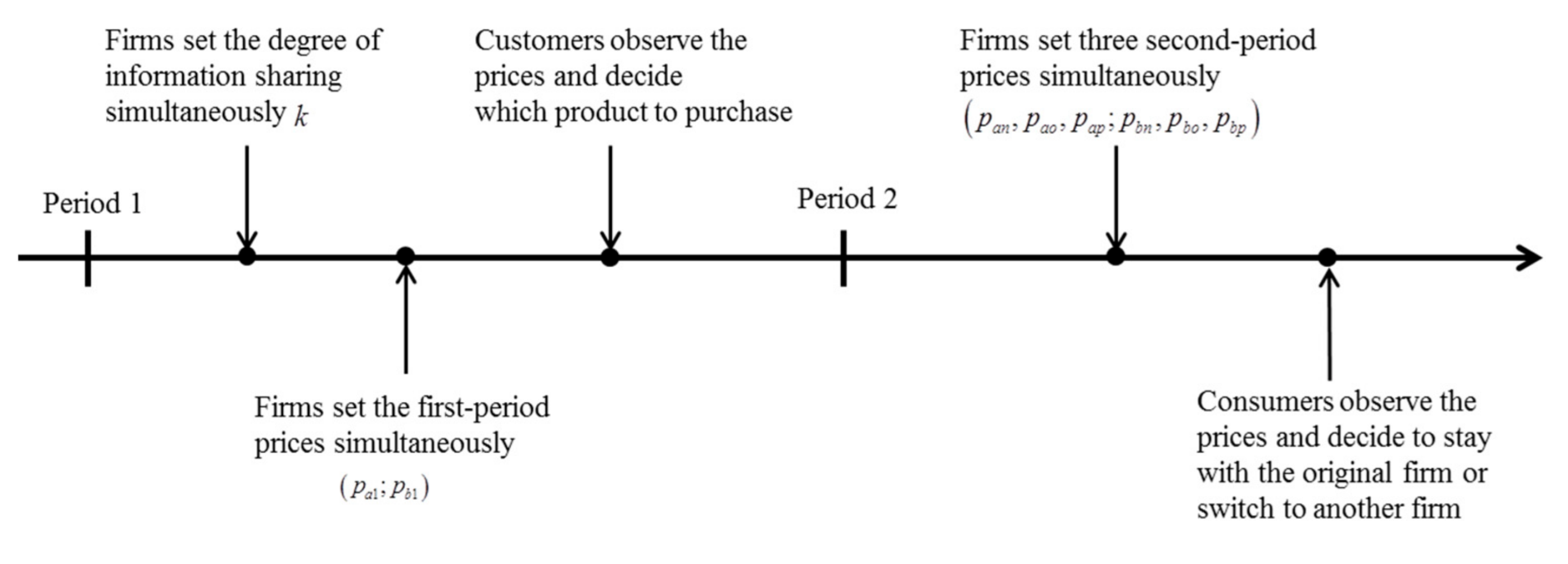

In this paper, S and M regulation are taken as a benchmark model, while the W regulation is formulated as the main model, as shown in

Figure 1, which is the timeline of the main model. Following the model setup in literature [

4] and using the backward induction method, we solve for the subgame Nash equilibrium of the model. Model hypotheses are as follows:

1. If the firm can collect consumer information, there is a privacy cost, , for consumers to stay with the original firm, which is an exogenous variable. If another firm holds the consumers’ information by sharing information between firms, there will also be a privacy cost when consumers buy from another firm, and this cost is related to the degree of information sharing among firms. We assume the cost is .

2. Under the W regulation, the degree of information sharing between firms, , is an endogenous variable, and the firms will share the information of the consumers who are farthest from the firms. In addition, there is a coordination cost in firm information exchange, and it is an exogenous variable, which is denoted as .

3. The marginal production cost of the two firms is standardized as zero.

6. Implications for Policy and Management

The maininsight from our analyses is that mandatory privacy protection does not necessarily lead to a higher social surplus, and the weak privacy regulation may put consumers in a better position, which depends on consumers’ product-privacy preferences and the cost of information coordination between firms. We discuss below some implications for policy and management.

At present, there are two main modes to protect personal information in the world, that are the “decentralized legislation plus industry self-discipline” mode represented by the United States, and the state-led consent legislation mode represented by the European Union. With the development of information technology, firms can not only easily obtain consumer information from the inside, but also collect information from the external environment, such as exchanging consumer information with competitors. Under the background that consumers pay more and more attention to personal information, the above conclusions are of great significance for the legislature to formulate appropriate privacy regulation measures. The conclusions of this paper reflect that the optimal social welfare depends on the consumer’s product-privacy preference and information coordination cost, which means that legislators can consider the mode of “decentralized legislation plus industry self-discipline”. The legislators can distinguish the consumer’s product-privacy preference in different industries with reference to some relevant research, so as to formulate appropriate privacy regulation measures for different industries. Legislators can exercise weak privacy regulation in industries where consumers pay more attention to privacy, which can improve social welfare to a certain extent. For example, the research results of Kummer and Schulte [

31] show that users of health and education related apps seem to be more privacy-sensitive than users of tools, entertainment, or games. Legislators may wish to implement weak privacy regulation in these industries, so as to improve social welfare to a certain extent. In addition, since the cost of information coordination among firms will affect which kind of regulation has the best social welfare, considering that the consumer surplus can reach the maximum under weak regulation, it is necessary to reduce the cost of information coordination among firms if the social welfare under weak regulation is to be optimized. This means that the government can encourage firms to use unified data recording technology, thus reducing barriers to information exchange among firms.

Our analysis also provides significant implications and applications for behavior-based pricing. We show that compared with pricing under the strong regulation, firms set lower prices for customers in each period under the weak regulation. In other words, in order to attract consumers and maximize profits, firms should set lower prices for customers under the weak regulation.

7. Conclusions

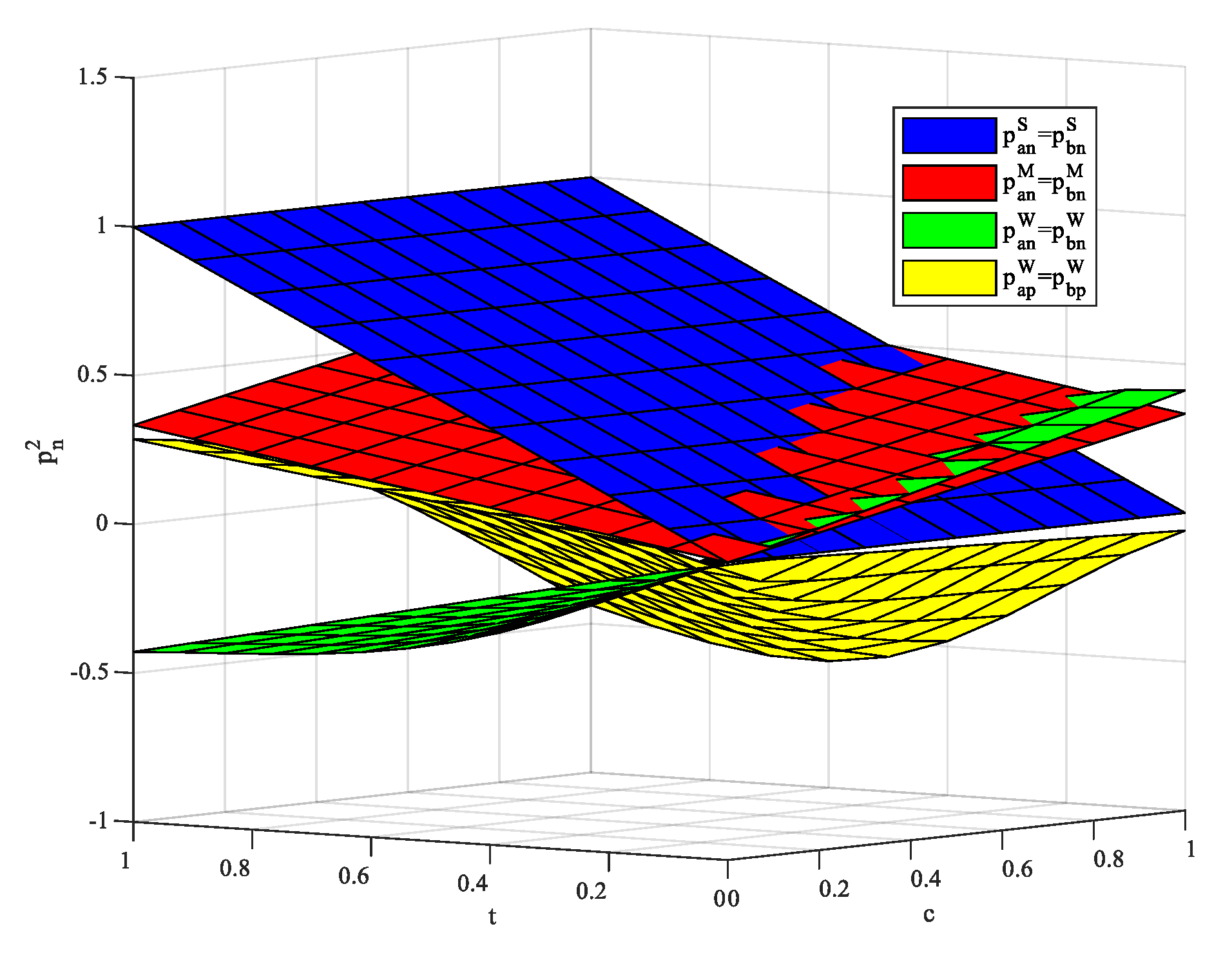

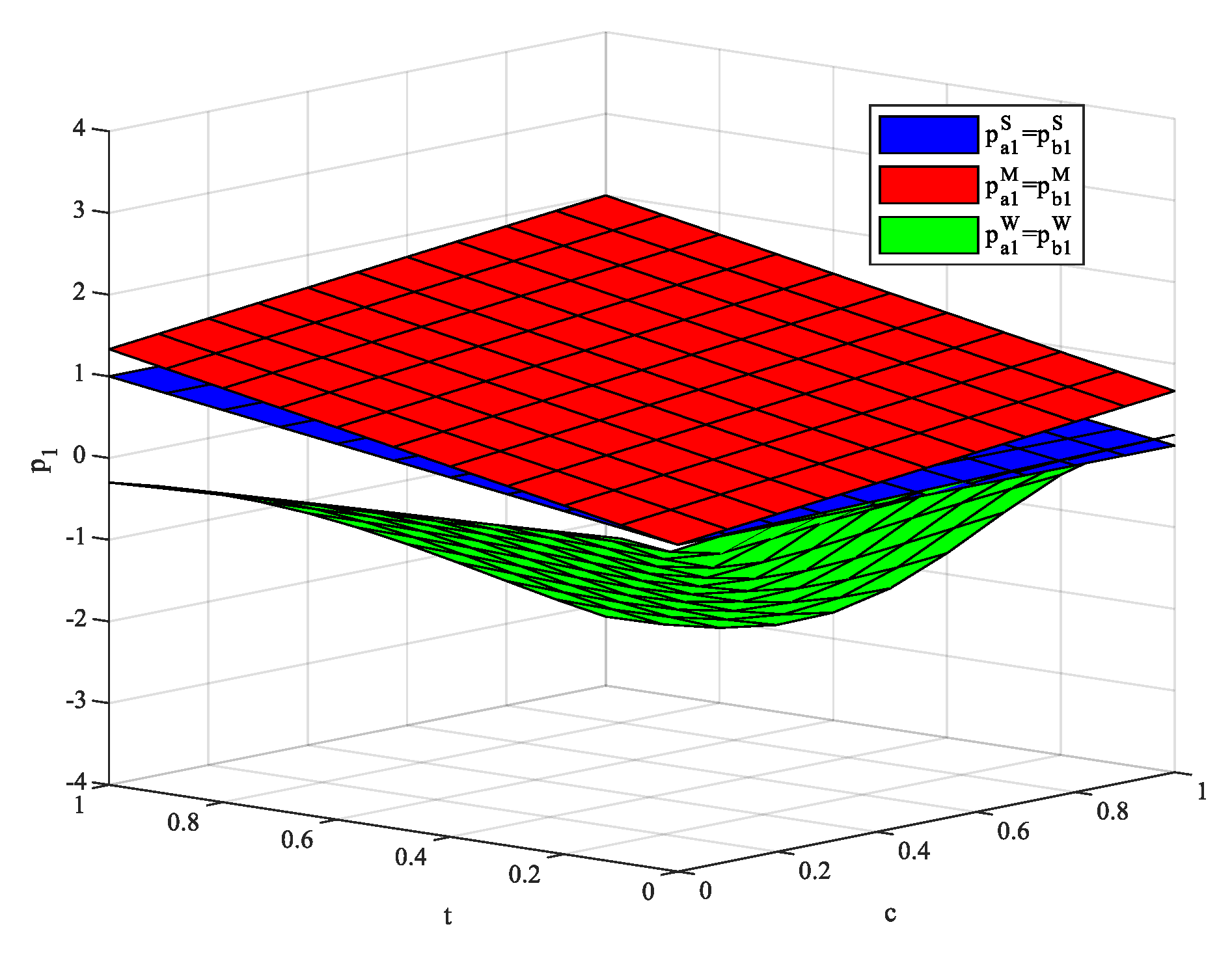

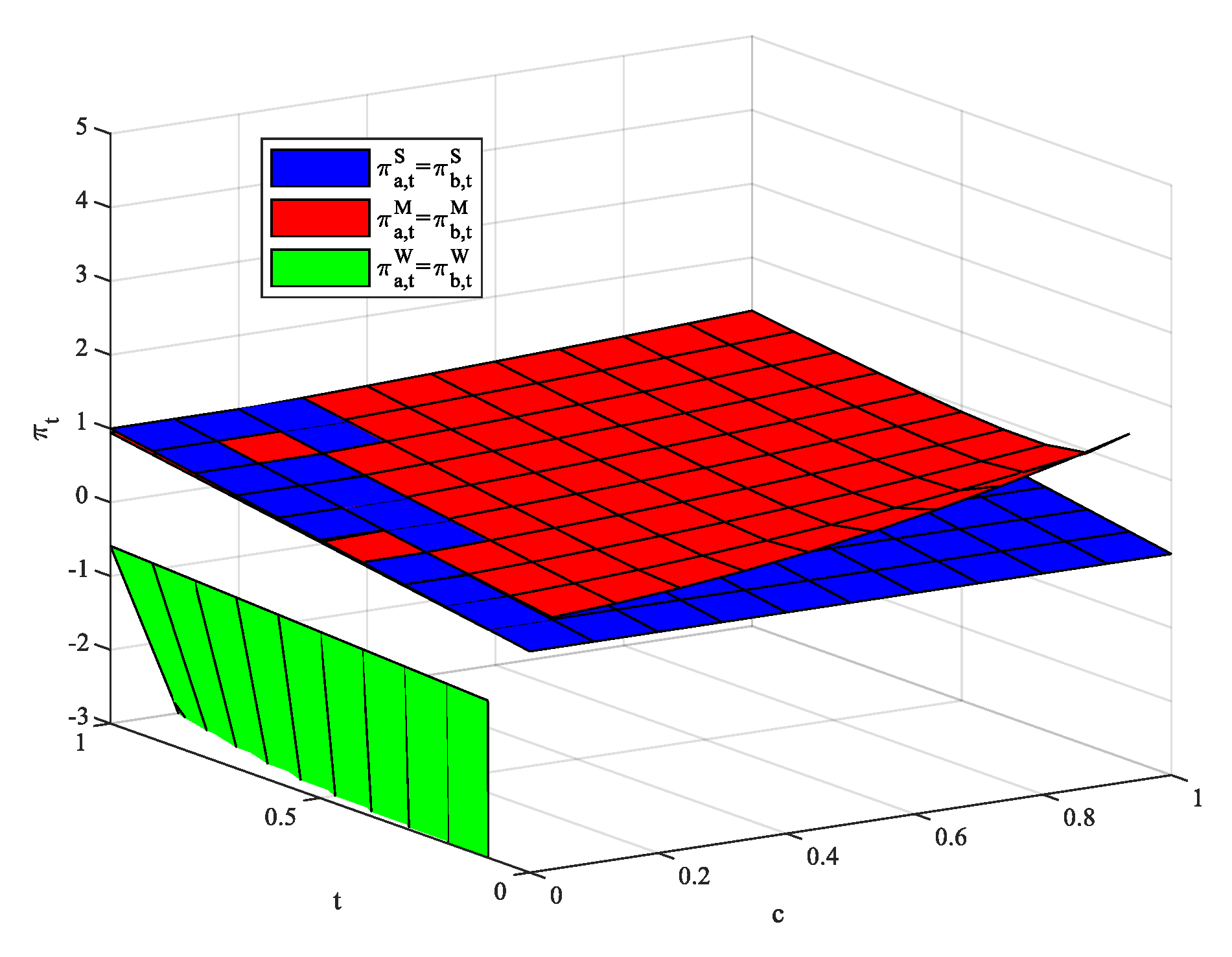

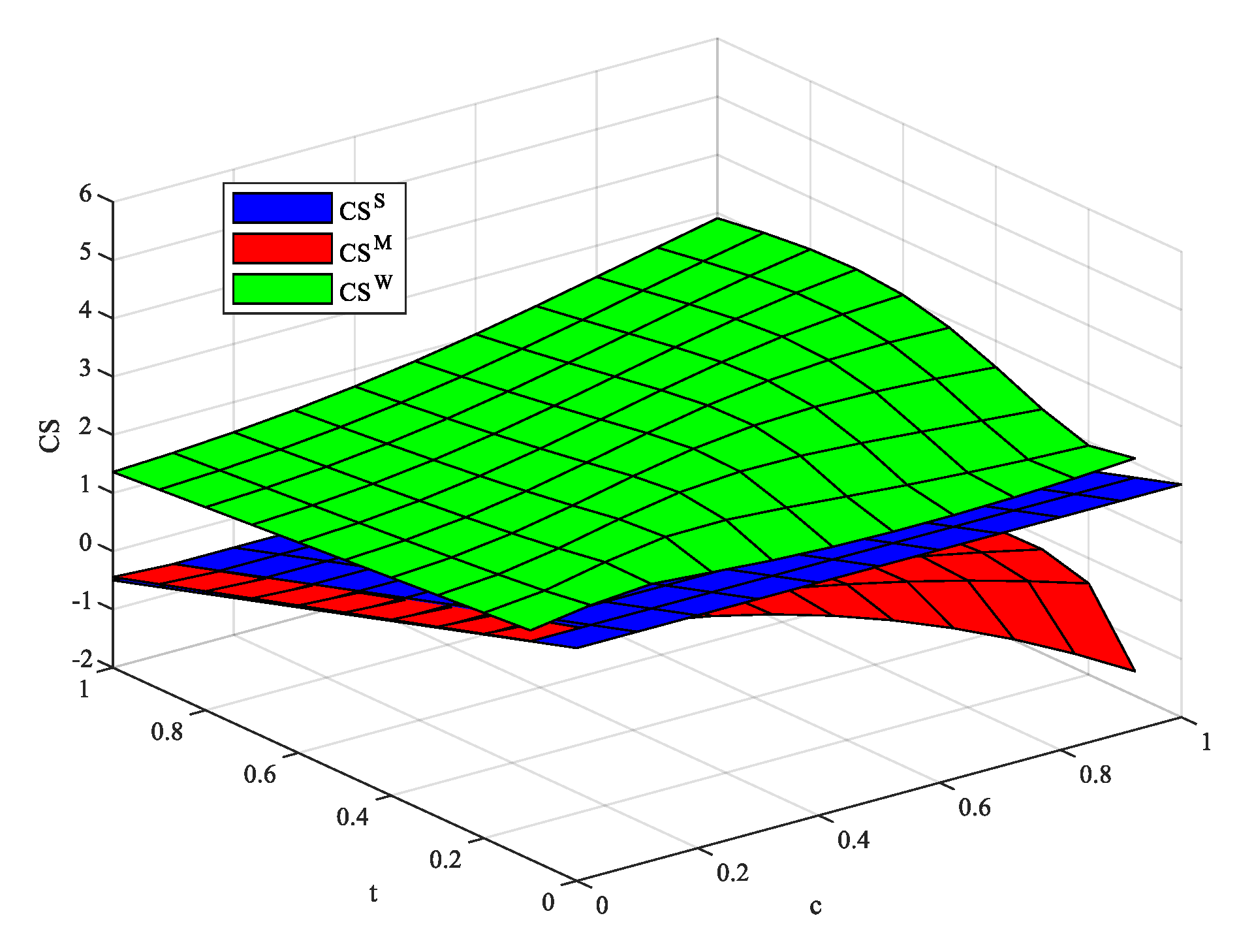

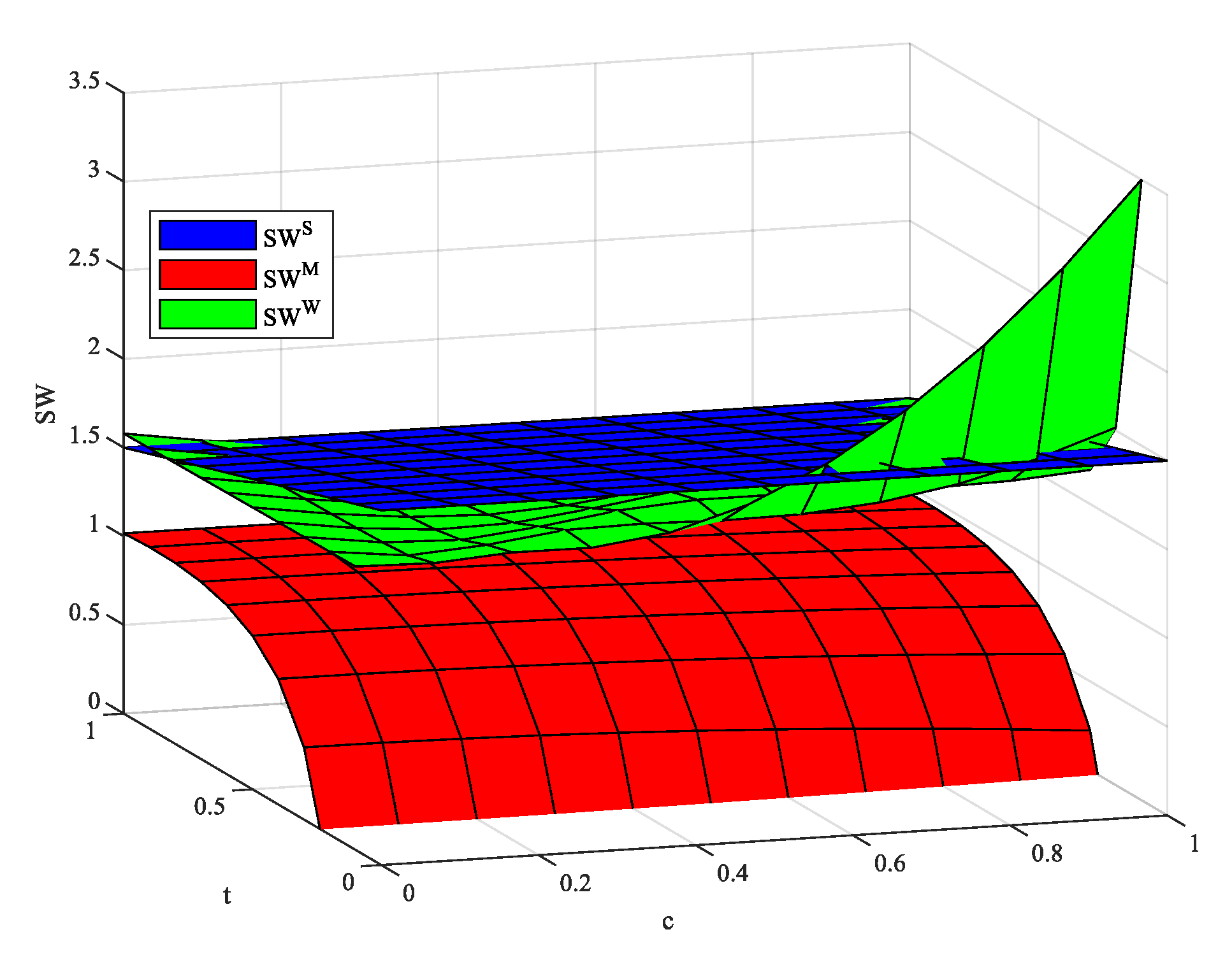

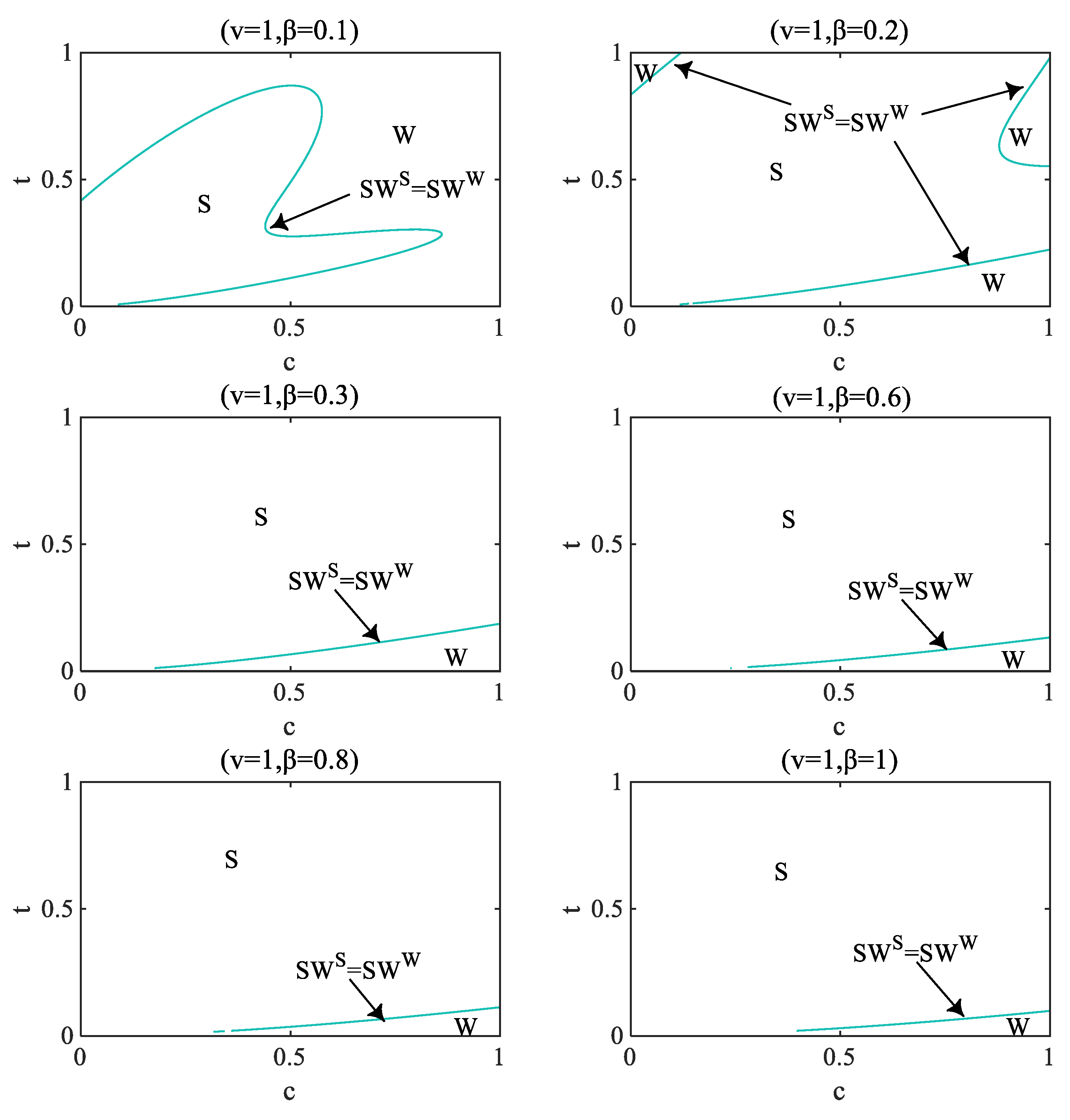

This paper constructs a two-period Hotelling competition game model, explores the industry profit, consumer surplus, and social welfare under three levels of privacy regulation concerning information sharing among firms, and uses MATLAB numerical simulation to simulate and analyze our main results. Through comparative analysis, the following conclusions are drawn: (1) under the W regulation, the total profits of firms are the lowest, while in most cases, the profits of firms under the M regulation are the highest. (2) Under the W regulation, the consumer surplus is the highest, while under the M regulation, the consumer surplus is the lowest. (3) When the cost of information coordination between firms is low, the social welfare is the highest under the W regulation; when the cost of information coordination is at a medium level, the social welfare under the S regulation is the highest; when the cost of information coordination is high, the social welfare is the highest under the S regulation and the lowest under the W regulation. (4) With the rising cost of information coordination among firms, it is only in areas where consumers have greater privacy preferences that social welfare may be optimal under the W regulation. Therefore, mandatory privacy protection does not necessarily lead to a higher social surplus. Similarly, the weak privacy regulation, which seems to harm consumers, may put consumers in a better position to a certain extent, which depends on the cost of information coordination between firms and consumers’ product-privacy preferences.

In this study, simplified assumptions, such as complete market coverage, single-homing, etc., are all aspects that can be considered in future research work. In addition, we can further consider the firm’s product quality strategy and discuss the firm’s pricing and product quality decisions under different privacy regulations.