Online Museums Segmentation with Structured Data: The Case of the Canary Island’s Online Marketplace

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Review of the Literature

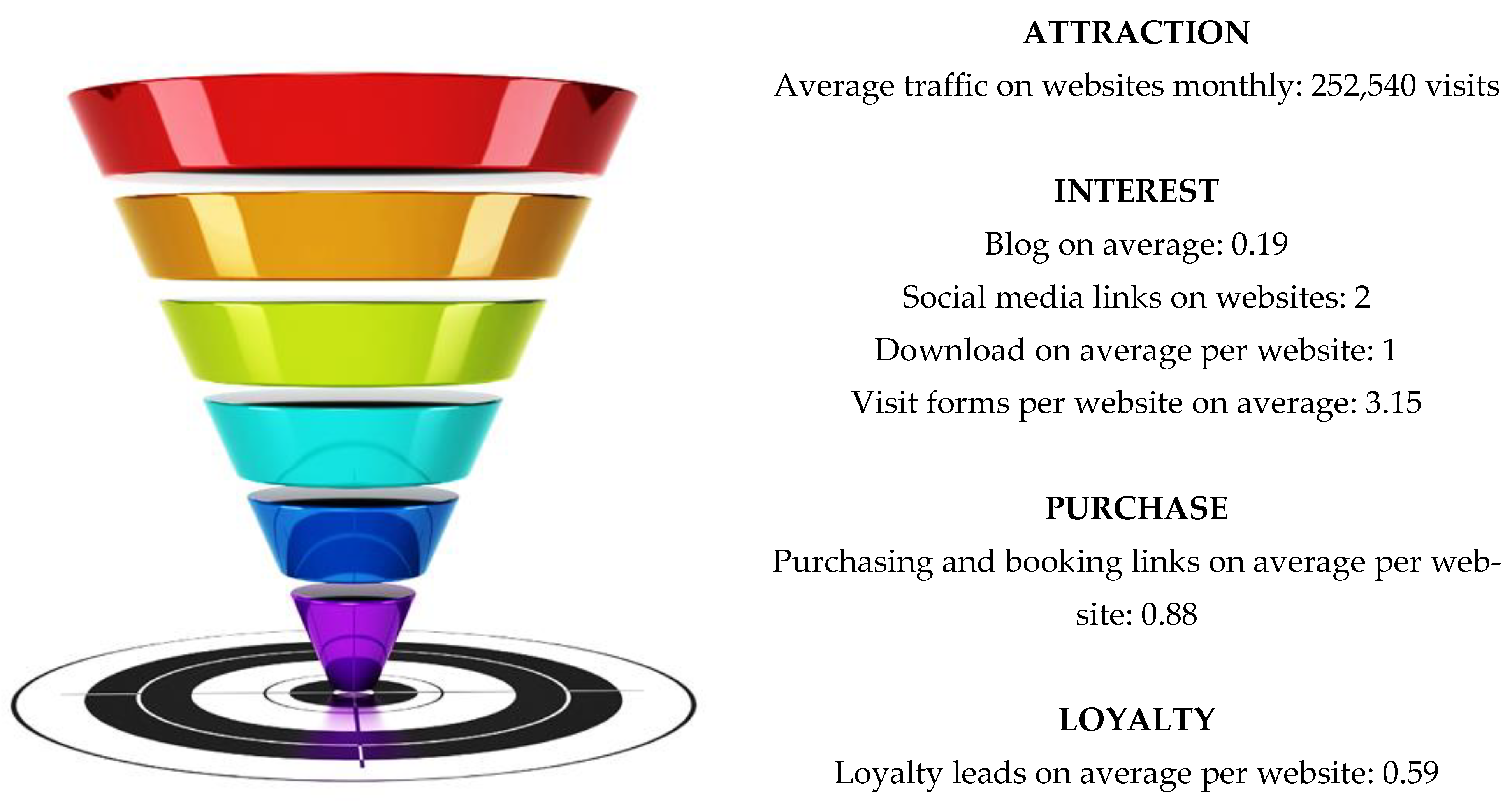

2.1. The Conversion Funnel and Its Phases

2.2. The Conversion Funnel Metrics as Criteria to Segment

2.3. The Interplay between Online and Offline Spaces

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Preliminaries

4.2. K Means Results

4.3. Cross Tabulation

5. Discussions, Implications and Limitations

5.1. Discussions

5.2. Implications

- The museums’ websites lack the development of loyalty tools so that they encourage repeat visitors.

- As far as three different segments have been identified, policymakers might implement specific policies toward each homogenous group so that users’ desired responses can be maximized.

- The potential exists to design the mobile application aimed at the evaluation of websites of cultural places. Cultural organisations using the application could check their performance at every stage of the conversion funnel in comparison to the museums that were examined in this research and search for recommendations on how to optimise the website quality.

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garcia-Madariaga, J.; Recuero Virto, N.; Blasco López, M.F.; Aldas Manzano, J. Optimizing website quality: The case of two superstar museum websites. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 13, 16–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawczuk, M. Application of the marketing innovation in the museum market. Int. J. Mark. Commun. New Media 2021, 9, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mudzanani, T.E. The four ‘C’s of museum marketing: Proposing marketing mix guidelines for museums. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2017, 6, 290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Herhausen, D.; Miočević, D.; Morgan, R.E.; Kleijnen, M.H.P. The digital marketing capabilities gap. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 90, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova, S. Design of customer perspective KPIs on the basis of purchase funnel approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Application of Information and Communication Technology and Statistics in Economy and Education (ICAICTSEE), Sofia, Bulgaria, 2–3 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhu, B.; Zuo, M. Integrating different types of targeting methods in online advertising. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS) 2016, Chiayi, Taiwan, 27 June–1 July; 2016; 303, pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K. Divisional advertising efficiency in the consumer car purchase funnel: A network DEA approach. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2020, 71, 1411–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.; Koutra, C. Evaluation of the persuasive features of hotel chains websites: A latent class segmentation analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 34, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gal-Or, E. Market Segmentation on dating platforms. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2020, 68, 102558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adukaite, A.; Inversini, A.; Cantoni, L. Examining user experience of cruise online search funnel. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2013, 8015, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiler, S.; Yong, S. The impact of advertising along the conversion funnel. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2017, 15, 241–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Haan, E.; Wiesel, T.; Pauwels, K. The Effectiveness of different forms of online advertising for purchase conversion in a multiple-channel attribution framework. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Mishra, S.; Gligorijevic, J.; Bhatia, T.; Bhamidipati, N. Understanding consumer journey using attention based recurrent neural networks. Proc. ACM SIGKDD Int. Conf. Knowl. Discov. Data Min. 2019, 3102–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepkowska-White, E.; Imboden, K. Effective design for usability and interaction: The case of art museum websites. J. Internet Commer. 2013, 12, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Meléndez, A.; Del Águila-Obra, A.R. Web and social media usage by museums: Online value creation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.A.; Carneiro, L. Communicating visual identities on ethnic museum websites. Vis. Commun. 2014, 13, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhishek, V.; Fader, P.; Hosanagar, K. Media exposure through the funnel: A model of multistage attribution. SSRN 2012, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bettman, J.R.; Luce, M.F.; Payne, J.W. Constructive consumer choice processes. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clow, D. MOOcs and the funnel participation. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, LAK, Leuven, Belgium, 8 April 2013; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo, V. Sales Funnel: Meaning, Advantages and Application in Content Marketing. 2013. Available online: https://marketingdecontenidos.com/que-es-un-funnelde-ventas/ (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Galiana, P. Why You Should Know What the Sales Funnel or Conversion Funnel Is. 2021. Available online: https://www.iebschool.com/blog/embudo-de-conversion-marketing-digital/#:~:text=El%20funnel%20de%20ventas%20o%20embudo%20de%20conversi%C3%B3n%20es%20una,de%20un%20producto%20o%20servicio (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Jansen, B.J.; Schuster, S. Bidding on the buying funnel for sponsored search and keyword advertising. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2011, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sirakaya, E.; Woodside, A.G. Building and testing theories of decision making by travellers. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Volchek, K. Bridging marketing theory and big data analytics: The taxonomy of marketing attribution. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 56, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brengman, M.; De Gauquier, L.; Willems, K.; Vanderborght, B. From stopping to shopping: An observational study comparing a humanoid service robot with a tablet service kiosk to attract and convert shoppers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 134, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimetz, J. B2B Marketing in 2007: The Buying Funnel vs Selling Process. 2007. Available online: http://www.searchengineguide.com/jody-nimetz/b2b-marketing-i-1.php (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Baum, N. Marketing Funnel: Visualizing the patient’s journey. J. Med. Pract. Manag. 2020, 36, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chapa, A. What is a Sales Funnel, Examples and How to Create One? Crazy Egg. Available online: https://www.crazyegg.com/blog/sales-funnel/ (accessed on 27 May 2021).

- Anderson, M.; Sims, J.; Price, J.; Brusa, J. Turning “like” to “buy” social media emerges as a commerce channel. Booz Co. Inc 2011, 2, 102–128. [Google Scholar]

- Colicev, A.; Kumar, A.; O’Connor, P. Modelling the relationship between the firm and user-generated content and the stages of the marketing funnel. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Azevedo, A.; Pomeranz, R. Customer Obsession: How to Acquire, Retain, and Grow Customers in the New Age of Relationship Marketing; McGraw Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, P.F. Relationship marketing strategies in the knowledge society. Ann. Fac. Econ. 2013, 1, 606. [Google Scholar]

- Kaila, S. How can businesses leverage data analytics to influence consumer purchase journey at various digital touchpoints? J. Psychosoc. Res. 2020, 15, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Building Customer-Based Brand Equity: A Blueprint for Creating Strong Brands. Master’s Thesis, Marketing Science Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, V.; Ali, R.T.M.; Thomas, S. Loyalty intentions. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2014, 6, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo García, M.D.L.A.; Muñoz Exposito, M.; Castellanos Verdugo, M. The expansion of social networks. A challenge for marketing management. Contab. Neg. 2015, 10, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Flores Gila, A. The Digitization of a Family Agribusiness; Final Degree Project; Universidad Pontificia Comillas: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fatta, D.; Patton, D.; Viglia, G. The determinants of conversion rates in SME e-commerce websites. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argento, A.D. Study of the Online Funnel Conversion of Strategic Consulting Companies in Spain. Master’s Thesis, Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, S.; Cooperstein, D.; Kemp, M.B. It’s Time to Bury the Marketing Funnel. Available online: http://www.iimagineservicedesign.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Customer-Life-Cycle-Journey.pdf (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Corson, S. Conversion Funnel: How to Build, Analyze and Optimize. Looker 2019. Available online: https://looker.com/blog/conversion-funnel-optimization (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Morgan, N.; Hastings, E.; Pritchard, A. Developing a new DMO marketing evaluation framework: The case of Visit Wales. J. Vacat. Mark. 2012, 18, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakkala, H.; Presser, K.; Christensen, T. Using Google Analytics to measure visitor statistics: The case of food composition websites. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2012, 32, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, I.; Bruno, H.A.; Feinberg, F.M. Wearout or weariness? Measuring potential negative consequences of online ad volume and placement on website visits. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Farris, P.W. Managing multi- and omni-channel distribution: Metrics and research directions. J. Retail. 2017, 93, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranlt, D.; Prantl, M. Website traffic measurement and rankings: Competitive intelligence tools examination. Int. J. Web Inf. Syst. 2018, 14, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, B.J.; Jung, S.G.; Salminen, J. Data Quality in Website Traffic Metrics: A Comparison Of 86 Websites Using Two Popular Analystics Services. Tech Report 2020. Available online: http://www.bernardjjansen.com/uploads/2/4/1/8/24188166/traffic_analytics_comparison.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Mergel, I. Building Holistic Evidence for Social Media Impact. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Thal, K. The impact of social media on the consumer decision process: Implications for tourism marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mehraliyey, F.; Liu, C.; Schuckert, M. The roles of social media in tourits’ choices of travel components. Tour. Stud. 2020, 20, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijayaa, A.P.; Pranantab, W. Tourist preference mapping: Does online information matter? A conjoint analysis approach. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2019, 5, 634–644. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, S.; Hudson, R. Engaging with consumers using social media: A case study of music festivals. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2013, 4, 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grincheva, N. How far can we reach? International audiences in online museum communities. Int. J. Technol. Knowl. Soc. 2012, 7, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Chan, J.; Tan, B.C.; Chua, W.S. Effects on interactivity on website involvement and purchase intention. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, M.E. A social media mindset. J. Interact. Advert. 2011, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colton, D.A.; Poploski, S.P. A Content Analysis of Corporate Blogs to Identify Communications Strategies, Objectives and Dimensions of Credibility. J. Promot. Manag. 2019, 25, 609–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Kwek, A.; Wang, Y. Cultural connectedness and visitor segmentation in diaspora Chinese tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiqiang, L. Design and Implementation of Fashion Music Resource Website Based on Asp. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1544, 012194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Guo, W.; Fu, L. Research on E-Government Website Satisfaction Evaluation Based on Public Experience. In Proceedings of the DEStech Transactions on Social Science, Education and Human Science, Xiamen, China, 20–21 April 2019; pp. 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Soler, I.; Martínez-Sala, A.M.; Campillo-Alhama, C. ICT and the sustainability of world heritage sites. Analysis of senior citizens’ use of tourism apps. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, D.; Park, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. The role of smartphones in mediating the touristic experience. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marty, P.F. Museum websites and museum visitors: Digital museum resources and their use. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2008, 23, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grün, C.; Werthner, H.; Pröll, B.; Retschitzegger, W.; Schwinger, W. Assisting tourists on the move: An evaluation of mobile tourist guides. In Proceedings of the 7 Internacional Conference on Mobile Business, Seoul, Korea, 7–8 July 2018; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lamsfus, C.; Wang, D.; Alzua-Sorzabal, A.; Xiang, Z. Going mobile: Defining context for on-the-go travelers. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoni, V.; Poulaki, I. Digital evolution and emerging reveneu management practices: Evidence from Aegean airlines distribution channels. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021, 12, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; Law, R.; Wen, I. The impact of website quality on customer satisfaction and purchase intentions: Evidence from Chinese online visitors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.S.; Bridges, M.; Commander, P. The Website Design and Usability of US Academic and Public Libraries: Findings from a Nationwide Study. Ref. User Serv. Q. 2014, 53, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neilson, L.; Madill, J. Using winery web sites to attract wine tourists: An international comparison. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2014, 26, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Teng, W. Contemplating museums’ service failure: Extracting the service quality dimensions of museums from negative on-line reviews. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepurda, H.M.; Liubych, A.S. Museum innovations: Digital technologies use. In Proceedings of the XI International Scientific and Practical Conference, Kharkiv, Ukraine, 19–20 March 2020; pp. 270–272. [Google Scholar]

- Geissler, G.L.; Rucks, C.T.; Edison, S.W. Understanding the role of service convenience in art museum marketing: An exploratory study. J. Hosp. Leisure Mark. 2006, 14, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancati, E.; Gordini, N. Content marketing metrics: Theoretical aspects and empirical evidence. Eur. Sci. J. 2014, 10, 92–104. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, M.; Katifori, A. Flow, staging, wayfinding, personalization: Evaluating user experience with mobile museum narratives. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2018, 2, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Portales, C.; Sebastian, J.; Alba, E.; Sevilla, J.; Gaitan, M.; Ruiz, P.; Fernandez, M. Interactive tools for the preservation, dissemination and study of silk heritage: An introduction to the silknow project. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2018, 2, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vito, G.; Sorrentini, A.; Di Palma, D.; Raiola, V.; Tabouras, M. New frontiers of online communication of small and medium museums in Campania region, Italiy. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2017, 7, 1058. [Google Scholar]

- Duguleană, M.; Briciu, V.A.; Duduman, I.A.; Machidon, O.M. A virtual assistant for natural interactions in museums. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunliffe, D.; Kritou, E.; Tudhope, D. Usability evaluation for museum web sites. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2001, 19, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukopoulos, Z.; Koukopoulos, D. Evaluating the usability and the personal and social acceptance of a participatory digital platform for cultural heritage. Heritage 2019, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Padron-Avila, H.; Hernández-Martín, R. Tourist attractions: Analytical relevance, methodological proposal and case study. Rev. Tur. Patr. Cult 2017, 15, 979–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, E.; Pencarelli, T.; Vesci, M. Museum visitors’ profiling in the experiential perspective, value co-creation and implications for museums and destinations: An exploratory study from Italy. In Proceedings of the HTHIC, Heritage, Tourism and Hospitality International Conference, Pori, Finland, 27 September 2017; pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wilkie, D.; Mokbel, M. Recommendations in location-based social networks: A survey. GeoInformatica 2015, 19, 525–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, G.; Stanislawski, R. Research online–purchase offline—A phenomenon among the young generation in the e-commerce sector. J. Int. Sci. Publ. 2018, 12, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Liege, J. Omnichannel and Holistic Consumer-Centric Metering. Available online: https://www.kanlli.com/ecommerce/omnicanalidad-y-medicion-holistica-centrada-en-el-consumidor/ (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Holdgaard, N. Online Museum Practices. A Holistic Analysis of Danish Museum and Their Users. PhD. Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gobierno de Canarias: Guía de Museos y Espacios Culturales de Canarias. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/opencms8/export/sites/cultura/patrimoniocultural/.content/PDF/guiamuseoscanarias.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2021).

- Pauwels, K.; van Ewijk, B. Enduring attitudes and contextual interest: When and why attitude surveys still matter in the online consumer decision journey. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 52, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, G.; Gaiser, C. Social Local Mobile, the Future of Location-Based Services; Springer: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mróz-Gorgoń, B.; Szymański, G. The impact of the ROPO effect in the clothing industry. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2018, 4, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burani, P. The ROPO effect: Measure, Search & Destroy. Search Engine Watch. Available online: http://searchenginewatch.com/article/2066218/TheROPO-Effect-Measure-Search-Destroy (accessed on 1 June 2021).

- González Fernández-Villavicencio, N. ROPO effect and libraries. Anuario ThinkEPI 2014, 8, 334–341. [Google Scholar]

| EL HIERRO | |

| Geological Interpretation Centre | Interpretation Centre of El Julan Cultural Park |

| Volcanological Centre | Guinea Ecomuseum |

| Ethnographic Center Casa de las Quinteras | Centre of the Biosphere Reserve |

| El Garoe Interpretation Centre | |

| FUERTEVENTURA | |

| Interpretation Centre Village of Atalayita | Archaeological Museum of Betancuria |

| Interpretation Centre of Cueva del Llano | Interpretation Centre of Jandia Natural Park |

| Juan Ismael Art Centre | Salt Museum of Salinas del Carmen |

| Casa Mané Art Centre | La Cilla Grain Museum |

| Doctor Mena House-Museum | La Alcogida Ecomuseum |

| Unamuno House-Museum | House of the Colonels |

| Morro Velosa Viewpoint and Interpretation Centre | Interpretation Centre of Tiscamanita |

| Lighthouse of La Entallada | Tradicional Fishing Museum |

| LA GOMERA | |

| Ethnographic Museum of La Gomera | Ethnographic Park of La Gomera—Los Telares |

| Archaeological Museum of La Gomera | |

| LANZAROTE | |

| International Museum of Contemporary Art | Aeronautical Museum of Lanzarote Airport |

| Cesar Manrique Foundation | Chinijo Museum |

| Visitors and Interpretation Centre of Mancha Blanca | César Manrique Haría House-Museum |

| Tanit Ethnographic Museum | The Timple House-Museum |

| Museum of Piracy | Yaiza Aloe Vera Museum |

| Punta Mujeres Aloe Vera Museum | El Grifo Museum of Wine |

| El Patio Agricultural Museum | Jose Saramago House-Museum |

| Atlantic Museum | Museum-Information Point Echadero de los Camellos |

| LA PALMA | |

| Interpretation Centre of the Marine Reserve | Ethnographic Museum of José Luis Lorenzo Barreto |

| Museum-Dressing Room of the Virgin of Las Nieves | Sacred Art Museum |

| Belmaco Archaeological Park | Casa del Maestro Ethnographic Museum |

| Interpretation Centre of La Bajada | Benahoarita Archaeological Museum |

| The Silk Museum | The Red House |

| Banana Museum | The Waffle Interpretation Museum |

| Naval Museum—Boat of the Virgin | Insular Museum of La Palma |

| La Zarza and La Zarcita Cultural Park | Puro Palmero Museum |

| El Tendal Archaeological Park | Interpretation Centre of Sugar Cane and Rum |

| Casa Luján Ethnographic Museum | The Plains of Aridane |

| City in the Museum of Contemporary Art Forum | Las Manchas Wine Museum |

| Visitors and Interpretation Centre of Cumbre Vieja Natural Park | Visitors Centre of Caldera de Taburiente National Park |

| GRAN CANARIA | |

| La Rama Museum | Municipal Museum of Arucas |

| The Martin Chirino Art and Thought Foundation | Casa los Yanez Ethnographic Museum |

| Tejeda Medicinal Plants Centre | Maipes de Agaete Archaeological Park |

| Antonio Padron House- Museum—Indigenous Art Centre | Canarian Museum |

| Finca Condal Museum | Abraham Cardenes Sculpture Museum |

| Triptych of Our Lady of the Snows | Cueva Pintada Archaeological Park and Museum |

| Mata Castle Museum | Panchito Ecomuseum |

| Museum of History and Traditions of Tejeda | Aguimes Interpretation Centre |

| Interpretation Centre of Casa del Fraile | Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art |

| La Zafra Museum | Leon and Castillo House-Museum |

| Interpretation Centre of Guayadeque | Ingenio Interpretation Centre |

| Elder Museum of Science and Technology | La Fortaleza Interpretation Centre |

| Aeronautical Museum of Canary Islands Air Command | Canary Museum of Meteorites |

| The Canary Island Craft and Stone Museum | Canary Islands Naval Museum |

| Interpretation Centre of El Pastoreo | Gando Tower Museum |

| Aguimes History Museum | Living Museum of La Aldea |

| Nestor Museum | Interpretation Centre of Las Salinas de Tenefe |

| Patrons of the Virgin House-Museum | Lugarejos Locero Centre |

| Colon House | Domingo Rivero Museum |

| Gofio Museum | Camarín Virgen del Pino Museum |

| Ethnographic Museum of Casas Cuevas | Perez-Galdos House-Museum |

| Lomo de los Gatos | Necropolis of Arteara |

| Ethnographic Centre of Valleseco | Labrante Interpretation Centre |

| Atlantic Centre of Modern Art | Tomas Morales House-Museum |

| Cenobio de Valerón | Arehucas Rum Distillery |

| La Regenta Art Centre | Interpretation Centre of El Paisaje |

| Nestor Alamo Museum | |

| TENERIFE | |

| Tenerife Aloe Vera Museum | Manuel Martín González Museum Room |

| Pinolere Ethnographic Museum | Science and Cosmos Museum |

| The Canary Islands Military History Museum | La Baranda Wine House |

| El Quijote Museum | Archaeological Museum of Puerto de la Cruz |

| Museum of Education of the University of La Laguna | Municipal Museum of Fine Arts |

| Sierva de Dios House-Museum | Ethnographic Guimar Pyramid Park |

| Eduardo Westerdahl Museum of Contemporary Art | Canarian Institute Museum—Cabrera Pinto |

| Nature and Man Museum | Sacred Art Museum of San Marcos’ Church |

| Sacred Art Museum 1 | Sacred Art Museum 2 |

| Natural Museum of Educational Mathematics | The Tenerife History and Anthropology Museum |

| Rooms Arts of the Government of the Canary Islands | The Carpet Museum |

| Los Sabandeños House-Museum | Captain’s House Museum |

| Tenerife Arts Space | History Museum Granadilla de Abona |

| Museo Sacro El Tesoro de La Concepción | Cristino de Vera Foundation |

| Castillo de San Cristóbal Interpretation Centre | Cha Domitila Ethnographic Museum |

| Juan Évora Ethnographic Centre | Ibero-American Craft Museum of Tenerife |

| Interpretation Center of the I and II International Exhibition of Sculptures on Street 1973 and 1994 | Santa Clara Museum of Sacred Art |

| Fisherman’s Museum | Zamorano’s House |

| PROCEDURE | Probabilistic at random <2% error with 95% reliability |

| POPULATION | Museums and cultural spaces in The Canary Islands |

| ELEMENTS | Websites of 155 museums |

| SAMPLING FRAMEWORK | List of museums provided by Dirección General de Patrimonio del Gobierno de Canarias |

| SAMPLING UNITS | The Canary Islands Museums websites |

| SAMPLING SIZE | 68 websites |

| CONTACT | Desktop, laptops and tablets with the internet connection used by 90 students of ULPGC |

| DATE | 4 and 6 May 2021 |

| PLACE | From the students’ households |

| CONTROL SYSTEM | Synchronic connection by TEAMS and submission through the ULPGC Virtual Campus |

| Descriptive Statistics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

| Traffic | 68 | 0 | 14,380,075 | 252,540.26 | 1,742,765.305 |

| Blog entries | 68 | 0 | 1 | 0.19 | 0.396 |

| 0 blog = 55 (80.9%); 1 blog = 13 (19.1%) | |||||

| Social Media | 68 | 0 | 7 | 2.03 | 1.931 |

| 0 social media = 20 (29.4%); 1 social media = 13 (19.1%); 2 social media = 12 (17.6%); 3 social media = 5 (7.4%); 4 social media = 8 (11.8%); 5 social media = 7 (10.3%); 6 social media = 2 (2.9%); and 7 social media = 1 (1.5%) | |||||

| Downloads | 67 | 0 | 16 | 1.03 | 2.516 |

| 0 download = 44 (64.7%); 1 download = 11 (16.2%); 2 downloads = 5 (7.4%); 3 downloads = 1 (1.5%); 4 downloads = 2 (2.9%); 5 downloads = 1 (1.5%); 6 downloads = 1 (1.5%); 10 downloads = 1 (1.5%); and 16 downloads = 1 (1.5%) | |||||

| Visit leads | 68 | 0 | 6 | 3.15 | 1.558 |

| 0 visit leads = 7 (10.3%); 1 visit lead = 7 (7.4%); 2 visit leads = 8 (11.8%); 3 visit leads = 10 (14.7%); 4 visit leads = 28 (41.2%); 5 visit leads = 9 (13.2%); and 6 visit leads = 1 (1.5%) | |||||

| Purchase leads | 68 | 0 | 10 | 0.88 | 1.792 |

| 0 purchase leads = 44 (64.7%); 1 purchase lead = 10 (14.7%); 2 purchase leads = 8 (11.8%); 3 purchase leads = 2 (2.9%); 6 purchase leads = 3 (4.4%); and 10 purchase leads = 1 (1.5%) | |||||

| Loyalty Leads | 68 | 0 | 4 | 0.59 | 1.026 |

| 0 loyalty leads = 46 (67.6%); 1 loyalty lead = 11 (16.2%); 2 loyalty leads = 6 (8.8%); 3 loyalty leads = 3 (4.4%); and 4 loyalty leads = 2 (2.9%) | |||||

| Final Cluster Centers | ||||||

| Cluster | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Traffic | −0.11701 | −0.12907 | 8.10639 | |||

| Blog entries | −0.26308 | 0.52713 | 2.04170 | |||

| Social media | −0.47670 | 1.02027 | 0.50252 | |||

| Downloads | −0.26239 | 0.60409 | −0.01186 | |||

| Visit leads | −0.22004 | 0.41922 | 0.54763 | |||

| Purchase leads | −0.32262 | 0.79127 | −0.49249 | |||

| Loyalty leads | −0.46758 | 0.93778 | 2.35163 | |||

| ANOVA | ||||||

| Cluster | Error | F | Sig. | |||

| Mean Square | df | Mean Square | df | |||

| Traffic | 33,338 | 2 | 0.005 | 64 | 7038.126 | 0.000 |

| Blog entries | 6.453 | 2 | 0.842 | 64 | 7.668 | 0.001 |

| Social media | 15.755 | 2 | 0.538 | 64 | 29.281 | 0.000 |

| Downloads | 5.233 | 2 | 0.868 | 64 | 6.031 | 0.004 |

| Visit leads | 3.010 | 2 | 0.930 | 64 | 3.236 | 0.046 |

| Purchase leads | 8.775 | 2 | 0.769 | 64 | 11.413 | 0.000 |

| Loyalty leads | 16.587 | 2 | 0.526 | 64 | 31.535 | 0.000 |

| Segment 1: 46; segment 2: 20; segment 3: 1 | ||||||

| Segments | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islands | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| El Hierro | Count | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | |

| % within Island | 80.0% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within Cluster | 8.7% | 5.0% | 0.0% | 7.5% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | 0.6 | −0.5 | −0.3 | |||

| Fuerteventura | Count | 5 | 2 | 0 | 7 | |

| % within Island | 71.4% | 28.6% | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within Cluster | 10.9% | 10.0% | 0.0% | 10.4% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | 0.2 | −0.1 | −0.3 | |||

| Gran Canaria | Count | 15 | 4 | 0 | 19 | |

| % within Island | 78.9% | 21.1% | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within Cluster | 32.6% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 28.4% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | 1.1 | −1.0 | −0.6 | |||

| La Gomera | Count | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| % within Island | 50.0% | 50.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within Cluster | 2.2% | 5.0% | 0.0% | 3.0% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | −0.6 | 0.6 | −0.2 | |||

| Lanzarote | Count | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 | |

| % within Island | 44.4% | 44.4% | 11.1% | 100.0% | ||

| % within Cluster | 8.7% | 20,0% | 100.0% | 13.4% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | −1.7 | 10 | 2.6 | |||

| La Palma | Count | 12 | 4 | 0 | 16 | |

| % within Island | 75.0% | 25.0% | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within Cluster | 26.1% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 23.9% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | 0.6 | −0.5 | −0.6 | |||

| Tenerife | Count | 5 | 4 | 0 | 9 | |

| % within Island | 55.6% | 44.4% | 0.0% | 100.0% | ||

| % within Cluster | 10.9% | 20.0% | 0.0% | 13.4% | ||

| Adjusted Residual | −0.9 | 1.0 | −0.4 | |||

| Total | Count | 46 | 20 | 1 | 67 | |

| % within Island | 68.7% | 29.9% | 1.5% | 100.0% | ||

| % within Cluster | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | ||

| Value | Approximate Significance | |||||

| Nominal by Nominal | Contingency Coefficient | 0.366 | 0.584 | |||

| Lambda | 0.014 | 0.314 | ||||

| Phi and V of Cramer | 0.393 | 0.584 | ||||

| The Uncertainty coefficient | 0.278 | 0.584 | ||||

| N of Valid Cases | 67 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Díaz Meneses, G.; Estupiñán Ojeda, M.; Vilkaité-Vaitoné, N. Online Museums Segmentation with Structured Data: The Case of the Canary Island’s Online Marketplace. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2750-2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070151

Díaz Meneses G, Estupiñán Ojeda M, Vilkaité-Vaitoné N. Online Museums Segmentation with Structured Data: The Case of the Canary Island’s Online Marketplace. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research. 2021; 16(7):2750-2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070151

Chicago/Turabian StyleDíaz Meneses, Gonzalo, Miriam Estupiñán Ojeda, and Neringa Vilkaité-Vaitoné. 2021. "Online Museums Segmentation with Structured Data: The Case of the Canary Island’s Online Marketplace" Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research 16, no. 7: 2750-2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070151

APA StyleDíaz Meneses, G., Estupiñán Ojeda, M., & Vilkaité-Vaitoné, N. (2021). Online Museums Segmentation with Structured Data: The Case of the Canary Island’s Online Marketplace. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 16(7), 2750-2767. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer16070151