Abstract

Generation Z spends much time on mobile Internet and less time accessing Internet services using desktop computers. These traits make them an important niche that can be targeted by retailers. The objective of the present study is to analyze the impact of online advertising, social influence, and usage motivation on the behavioral intention related to m-commerce use among Romanian young adults. The research methodology is based on applying partial least square equation modelling (PLS-SEM), using data collected through a questionnaire. The proposed structural model includes four constructs that are first order reflective. The results reveal that among the influencing factors that determine Generation Z to use m-commerce, the usage motivation factor is the most important one, followed by social influence and online advertising. The research is useful for marketing professionals and retailers in establishing marketing strategies in accordance with the factors that influence the buying decision of young adults, representing Generation Z.

1. Introduction

M-commerce has gained more popularity in recent years compared to e-commerce [1,2,3], because of technology development, use of smartphones on a large scale, and recent trends in consumer behavior. M-commerce refers to transactions made online using mobile devices, while e-commerce incorporates both this type of commerce and also the one in which consumers use their computer.

The share of mobile commerce in e-commerce increased from 52.4% in 2016 to 70.4% in 2020, with an estimation of 72.9% for 2021, at a global level [1,2]. The value has more than doubled in 2020 (2.91 trillion dollars) compared to 2017 (1.36 trillion dollars), in absolute value [2]. Many people use multiple devices to complete their buying decision, from the stage of gathering information about the product to the stage of finally paying for the product. The tendency is that mobile devices will be much more used, both at the beginning and at the end of the transaction, compared to the use of computers [2].

Even if the general understanding of the term m-commerce refers to the online purchase of goods using mobile devices, m-commerce also includes mobile banking and mobile payments [4]. According to the World Payments Report [5], 46.1% of those who buy online prefer mobile banking. The report also emphasizes that the percentage of people buying goods and services online before the COVID-19 pandemic (24%) almost doubled during the pandemic (47%).

Other changes, highlighted in the report [5], show that all the generations’ representatives used more the mobile payments (digital wallets and payments with QR codes), the overall increase being 53% during the pandemic. The change in their behavior will probably remain stable, if we consider the length of the pandemic and the psychology of habits, according to which a learning phase takes about 2–3 months [6].

The changes in the way people prefer to buy nowadays or to use their banking accounts represent an important challenge for businesses and a great opportunity for them to sell more. In order to succeed, companies should invest in their mobile website, develop mobile apps and have a responsive platform [7], because younger generations prefer fast transactions and dislike a website or an app that has loading issues [8].

Companies should target consumers who use their mobile devices in each stage of the buying process [9], considering the importance played by these devices in everyone’s lives nowadays. The abandonment rate of the selling cart is one of the frequent issues that raises for the companies selling online is. The results of a study conducted by Barilliance [10] show a higher abandonment rate for those that buy online using their smartphones (80.79%) than for those that buy online using their computer (73.93%), the global abandonment rate of the online shopping cart being 77.73% in 2019.

Many factors influence the magnitude of mobile transactions and these are: “age, social class, and behavior patterns” [11] (p. 193) but also region [12] and culture. The present research highlights the consumer habits of young adults of Generation Z in relation to mobile commerce.

A research conducted by Episerver [13] revealed some differences between generations in terms of their preference for using smartphones when buying online. Thus, Generation Y and Generation Z show a higher inclination towards m-commerce: 58% for the Generation Y and 49% for the Generation Z.

The report [13] also analyzes the differences between generations regarding the mobile device (phones, smartwatches or tablet) they mostly use when buying online: 65% of the Generation Y’s representatives use mobile devices; 55% of Generation Z’s representatives use mobile devices and 33% of Baby Boomers use mobile devices.

The factors that are presented in the relevant literature as having an influence on the online shopping behavior are: behavioral intention [14] or online shopping intention [15] as independent variables and, dependent variables, such as perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use [14,15,16,17], enjoyment [14,15,17], trust [14,16,17,18], innovativeness, anxiety, skillfulness, relationship with the brand [14], convenience [18], social influence/social networks [17,18], and advertising [18].

The current paper investigates the key factors that impact the mobile commerce behavioral intention from the perspective of the young adults (19–25 years old) in Romania. Thus, the behavioral intention of these youngsters will be analyzed through the lens of three variables: online advertising, social influence, and usage motivation.

Other studies also analyze the influence of several variables on Generation Z’s behavioral intention. However, these studies do not focus on Romanian young adults, part of Generation Z, who represent a dynamic segment of the market, taking into account their inclination for m-commerce.

This research is highly important, due to the fact that Generation Z represent a valuable niche for companies’ representatives, who can better focus on their needs, while designing the marketing campaigns, if there is advanced knowledge regarding the factors that influence the buying decisions of this generation.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

Generation Z’s representatives are born between 1995 and 2010, defining the generation of people aged roughly 10 to 25 years old (teenagers and young adults). Generation Z spends much time on mobile Internet and less time accessing the Internet services using desktop computers. Most of the 25-year-olds have already their first salary or their own place to live.

According to AdColony report, this generation represents “a main target for brands” [19] (p. 3), at least after they start working and gaining much money. The report shows that 97% of Generation Z own a smartphone, but only 69% own a computer. At the same time, their perception is that the role played by phones in the last years increased, while the importance of laptops and desktop PC decreased [19,20]. They also spend more hours on their mobile devices than on their computers, and 61% of them prefer buying online using their mobiles [19].

Generations are different in terms of the importance associated to their smartphones [20]: 78% of Generation Z appreciate that phones are the most important devices, but this percentage decreases for Generation Y (74%), Generation X (61%), and Baby Boomers (37%), this being an indicator of their online shopping behavior.

Mobile payments are also an important part of m-commerce and there are differences between generations also [21]: 31% of people aged between 16 and 24 years old made a mobile payment in the last month, 35% of people aged between 25 and 34 made a mobile payment in the last month, while after the age of 35 this percentage decreases gradually reaching the level of only 13% for those above 55 years old. Another important trend refers to the use of QR codes on their smartphones [22]: 41% of youngsters aged between 16 and 24 years old used this technology in the previous month, this percentage being higher in Asian countries.

These statistics are useful for building a better image on the consumption and behavior patterns of young adults. There is an increased interest in knowing and understanding this generation by the companies, in order to influence these youngsters to buy products and to become loyal to the brands.

For analyzing the m-commerce level of use among Romanian young adults, the present study starts from developing three hypotheses in which factors like online advertising, social influence, and usage motivation have a positive impact on behavioral intention.

2.1. Behavioral Intention

Several authors analyzed behavioral intention [23], using it as an endogenous latent variable in the proposed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM).

Behavioral intention is a variable analyzed in many papers [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31] in relation to different behaviors. Even though this term is specific to psychology, it has multiple applications in other fields. Thus, it is important to know what the factors that influence the intention to buy a product are, in order to tailor the marketing strategies to the needs of a specific niche of consumers, within the online retail industry. If we only refer to buying online, this behavioral intention might be replaced also by online purchase intention or online shopping intention. Behavioral intention is influenced by various risks perceived when shopping online: desire, “attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control” [25] (p. 6), perceived usefulness [26,27], the country’s culture and its economic development [27], trust and commitment [29], perceived ease of use, enjoyment, variety, and innovation [31].

In our research, we analyze three factors with a positive impact on the behavioral intention of Generation Z’s young adults: online advertising influence, social influence and usage motivation. However, there are other studies in the literature that follow other influencing factors, such as “price, trust, reputation of retailers, education and age” [28] (p. 128), we have chosen the presented variables based on recent findings in this field, moreover in the current context of COVID-19 pandemic.

2.2. Online Advertising Influence

Online advertising influence is used as an exogenous latent variable in PLS path modeling. This factor is also presented in other studies as “online marketing communication” [32], “social media advertising” [33] or “online viral marketing” [34]. Thus, it was noticed that there is a “direct and positive” connection between the “attitudes towards online communication” [32] (p. 245) and the intention of users to buy a product or at least search for more information.

Advertising through social media is of utmost importance, especially for targeting younger generations who spend much time on their phones and on social media channels. Zhang and Mao [33] explain the complex psychologic path from the motivation to click on an ad (enjoyment or curiosity) to the users’ intention and, finally, to the buying act. Haryani and Motwani [34] highlight the consistent impact of viral marketing on the behavioral intention of those targeted through these types of campaigns.

Starting from the connection between these two variables, we developed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Online advertising has a positive impact on behavioral intention.

2.3. Social Influence

Social influence is used as an exogenous latent variable in PLS path modeling.

This variable refers to the influence exerted on the individual by family, friends, influencers, celebrities or by what the individual thinks in relation to these people that are important to him. Khatimah et al. [35] (p. 1) point out that social influence has “a significant effect on behavioral intention”. Ryan [36] and Bonfield [37] also analyze the impact of social influence in conjunction with behavioral intention and, finally, the decision to buy.

In a report of Global Web Index [38] (p. 8), it is shown that 42% of the respondents “use social networks to research products”, 24% of the respondents access social networks to “discover brands via recommendations/comments on social media” and 21% of the respondents are “motivated to purchase by a buy button on a social network”. These numbers show the impact of social media on the intention to buy a product, on which individuals first do research, after being influenced by other people’s opinions.

Yin et al. [39] analyze different dimensions of social interaction, one of them being intimacy. They reached the conclusion that intimacy between people (users on a platform, friends, peers) had an important impact on the purchase intention, but this connection was mediated differently, depending on the cultural background.

The following hypothesis was developed in order to analyze the connection between social influence and behavioral intention of Generation Z, while using mobile commerce:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Social influence positively impacts behavioral intention.

2.4. Usage Motivation

Usage motivation is employed as an exogenous latent variable in PLS path modeling. Usage motivation covers factors such as perceived usefulness and ease of use, but also enjoyment [26,27,31]. Fard et al. [40] analyze the impact of utilitarian and hedonic motivation on the purchase intention, considering variables like performance and effort expectancy, facilitating conditions, price value and, conclude that both the utilitarian and hedonic motivation have a strong influence on the intention to buy online. Topaloglu [41] also presents the impact of hedonic and utilitarian factors on the intention to shop online.

Kim [42] uses motivational factors such as time and cost to analyze the impact on online purchasing intention, but also the perceived ease of use. The author also analyzes the factors that represent a barrier to e-commerce like those related to privacy and the associated risks. Stefany [43] includes in the motivational factor leading to the intention to buy online the following factors: perceived value people expect to receive, perceived performance and effort implied, enjoyment and customization.

The following hypothesis was considered for analysis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Usage motivation has a positive impact on behavioral intention.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Method

The research method is based on applying partial least square equation modelling (PLS-SEM), using data collected through a questionnaire. This method was chosen based on the fact that the recent research has moved towards PLS-SEM, in order to analyze composite-based path models. Hair et al. [44] provided a list to check if PLS is recommended for a research using SEM, from which we underline: “when the structural model is complex and includes many constructs, indicators and/or model relationships”; “when research requires latent variable scores for follow-up analyses”.

The hypotheses are developed beginning from the latest theoretical findings on m-commerce that take into consideration: behavioral intention, social influence, usage motivation. We considered the latest research in the field, because the characteristics of Generation Z are in a continuous evolution, due to their connection to technology and the high level of Internet usage.

3.2. Data Collection

The data used is our analysis were collected through a primary research, using the questionnaire as a gathering tool. The questionnaire was composed of two sections: constructs of the model (1) and demographic questions (2). Thus, the questions in the questionnaire covered the following constructs (Appendix A—Table A1):

- (1)

- Behavioral intention, items previously used [45,46,47].

- (2)

- Online advertising influence, items added by authors, not previously used.

- (3)

- Social influence, items previously used [23,47].

- (4)

- Usage motivation, items previously used [46,47,48].

Each item was measured with a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“Totally disagree”) to 5 (“Totally agree”).

3.3. Sample Description

The questionnaire was distributed online to over 1000 young adults, part of the Generation Z, and, after removing the incomplete responses, we got 217 valid questionnaires. The respondents are aged between 19–25 years old, accounting for 75.6% females and 24.4% males. Most participants have their bachelor’s degree (64.5%) and are unemployed (63.6%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the demographic information of the sample.

3.4. Structural Model

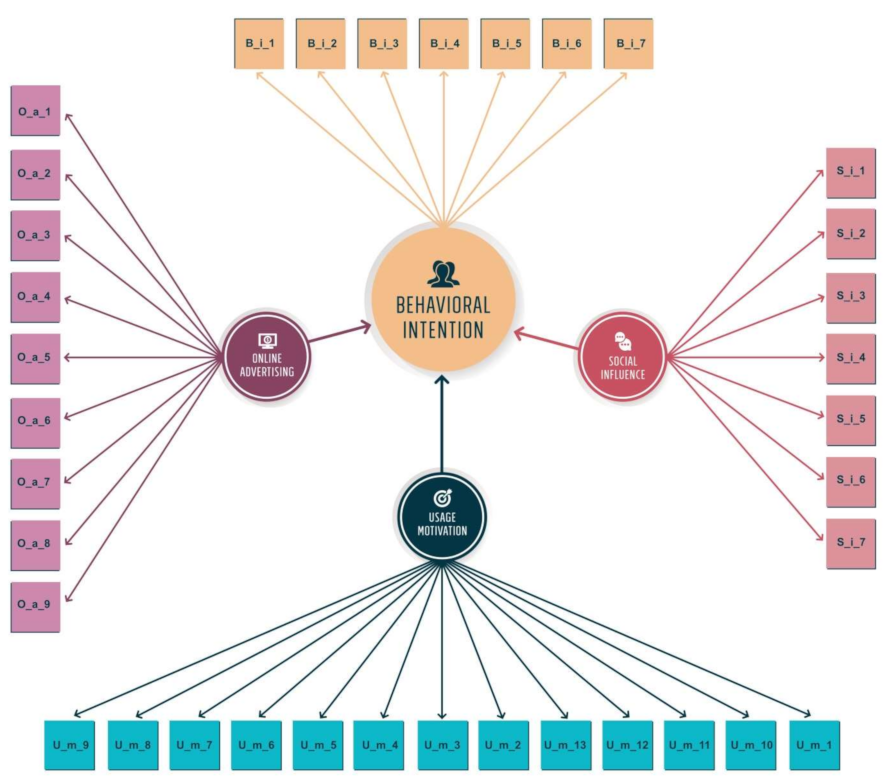

In order to assess the proposed model, partial least square equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was employed, using SmartPLS v3 software. The proposed structural model includes four constructs that are first order reflective (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual structural model. Source: Authors’ own analysis using SmartPLS v3.

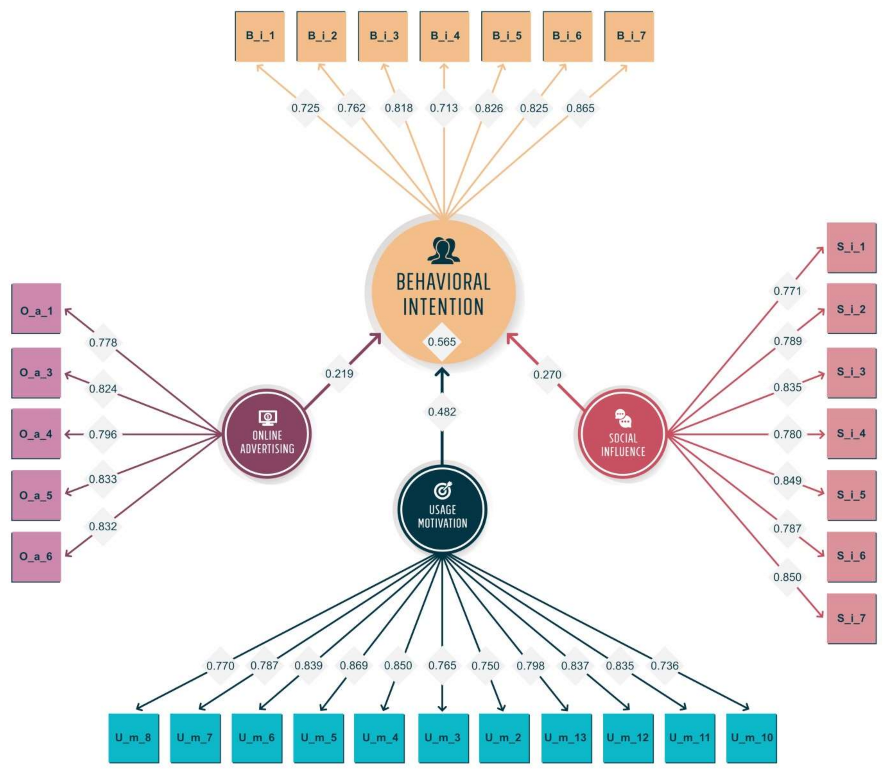

Items’ validity required that each indicator loading is over 0.7 or above, based on the correlations between the latent variable and the indicators. Four items for Online advertising and two items from usage motivation, in seven iterations, were removed within the structural model (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual structural model. Source: Authors’ own analysis using SmartPLS v3.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Reliability and Validity

It is important to establish the reliability and the validity of the latent variables in order to complete the examination of the model. All Cronbach’s Alphas exceed 0.8, underlining a high internal consistency of indicators measuring each construct. All the average variance extracted (AVE) values are higher than 0.6, so convergent validity is confirmed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Construct Reliability and Validity.

Discriminant validity is assessed. There can be observed that the square roots of AVE (in bold on the matrix diagonal) are above the absolute correlations between constructs. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Fornell-Larcker Criterion Analysis for checking Discriminant Validity.

We also analyzed Bootstrap t- statistics for significance of the model. Using the two-tailed t-test with a significance level of 5%, the path coefficient will be significant if the T-statistics are larger than 1.96. All the path coefficients are statistically significant (Table 4).

Table 4.

T-Statistics of Path Coefficients.

4.2. Assessing Structural Model

Standard assessment criteria include collinearity statistics (VIF), the coefficient of determination (R2), the predictive relevance through the blindfolding-based cross-validated redundancy measure (Q2), the statistical significance and relevance of path coefficients. Before testing the structural model, the fit adjustment with SRMR value was 0.086, which indicates a good fit adjustment.

VIF values should be lower than 5, which was verified in the model. The next step was the analysis of R2 of the endogenous constructs. Three constructs Usage motivation, Behavioral intention and Online advertising can jointly explain 56.5% of the variance of the endogenous construct Behavioral intention. Q2 value is 0.326, depicting medium predictive relevance of the structural model.

Thus, it can be seen that the proposed structural model presents the estimations of path coefficients and respective significances. All the hypothesized paths are statistically significant (H1. Online advertising has a positive impact on behavioral intention; H2. Social influence positively impacts behavioral intention; H3. Usage motivation has a positive impact on behavioral intention). Online advertising influence, social influence, and usage motivation show significant positive impacts on behavioral intention.

Means and standard deviations of the retained items are presented in Table 5. Means vary from 2.585 (I have bought products/services though mobile commerce, because sports people advertised them) to 3.907 (I will continue to use the mobile commerce to shop for new products) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of the retained items.

5. Discussion

Several factors, including but not limited to online advertising, social influence, and usage motivation, influence behavioral intention. Resources have to be allocated in these directions. Out of these three factors, usage motivation is the most important one (0.482), followed by social influence (0.270) and online advertising (0.219). This means the company should emphasize usage motivation, in case there are no available resources to manage all three areas simultaneously. However, this variable is very important due to the fact that it is situated as one of the “starting points of purchase decisions” [49]. Usage motivation is not a single-dimension factor, being influenced by the following elements: information about products/services at any time; needed information at any time; fun of using m-commerce; the enjoyable feeling of using m-commerce; entertainment in using m-commerce; a sense of adventure while using mobile commerce; rewarding part of using m-commerce; many features provided by m-commerce; fulfillment of different tasks and functions in an efficient way; helpfulness in buying and searching online. Our proposal is that the companies should allocate resources in this way, if these are limited.

In terms of implications for marketing theory, we can state that the novelty of our research consists in adding a new variable, online advertising influence, to the developed model. Comparing our results to past research, we can underline the similarities and the differences with our results. Thus, following the work of Dakduk et al. [23], social influence did not have an impact on behavioral intention. However, our results are in accordance to the results obtained by Sivathanu [50] and Savita Panwar [51] that confirm a significant positive impact of social influence on behavioral intention. According to Zhang et al. [52], this result is more appropriate in cultures with “high scores in power distance and masculinity”. In accordance to the results of Dakduk et al. [23], usage motivation, also named “hedonic motivation” has a significant positive impact on behavioral intention. Moreover, information value, convenience value, and performance have a significant positive effect on hedonic motivation [46]. From the findings of Omar et al. [45], customer satisfaction has a significant positive impact on usage motivation, also named “customer loyalty”.

In terms of implications for marketing practice, the paper offers valuable results, in order to improve m-commerce practices. Companies should consider online advertising when establishing their budgets, as Generation Z’s representatives can be targeted by online promotional actions. However, the marketing decision makers can use the results of our research in order to compare the influence on behavioral intention of other alternative activities, that were already implemented within the company, such as, media advertising, direct marketing, loyalty programs, membership cards etc.

On the other hand, even if Generation Z is an online generation, with its representatives being born in the digital age, there are several factors that we need to consider in analyzing the results. The income is lower for younger generations, most of them being unemployed or at the beginning of their career. However, the evolution of the standard of living is different at the level of the European Union member states, being impacted by the following variables: “population, density of the population and inflation rate” [53].

The approached topic is of importance for the concerned parties: researchers, practitioners and companies, moreover in the current context generated by global COVID-19 crisis. This pandemic revealed to all the experts in this field that the companies need fast decisions and actions in this turbulent environment. The current reality proves that the customers, regardless their age, avoid physical stores, an opportunity that has to be considered by the companies selling online, in order to allocate resources in this regard, especially towards the use of mobile commerce and mobile apps.

6. Conclusions

The results of the current paper revealed the key factors that impact the mobile commerce behavioral intention of Romanian young adults, part of Generation Z. Thus, our results validated three hypotheses, from the perspective of m-commerce use among Romanian young adults: H1. Online advertising has a positive impact on behavioral intention; H2. Social influence positively impacts behavioral intention; H3. Usage motivation has a positive impact on behavioral intention.

The current study has several theoretical and methodological limitations. In terms of theoretical limitations, the proposed model was validated on the young adults from Romania that have skills to use Internet connected devices. However, in Romania there is an important part of Generation Z’s representatives, mainly from rural areas and part of disadvantaged groups, that does not meet these skills, although the number of internet users had an ascendent trend in our country during the recent years (70% of Internet users in 2017; 77% of Internet users in 2018; 80% of Internet users in 2019; 85% of Internet users in 2020) [54].

Regarding the methodological limitations, partial least square equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was used as the research method using data collected through a questionnaire. The questionnaire was composed of two sections (constructs of the model and demographic questions), it was distributed online to the over 1000 young adults, part of the Generation Z, and, after removing the incomplete responses, we got 217 valid questionnaires. Due to the fact that our chosen method is seen as having “numerous typically very restrictive assumptions” [44], the analysis can also be done using the software AMOS developed by IBM, which can help us to estimate the model parameters, “by only considering common variance” [44].

Additionally, we propose further research on a panel sample in order to test the main influences on the behavioral intention on the long run. Another option for further research will be to test the model on different market segments in order to be able to make comparisons between these, following the steps towards “a digital society at the level of the European Union’s countries” [55], from the perspective of the Digital Single Market Strategy for Europe. The research model can also be developed by including other key marketing constructs, such as “customer engagement and experience” [45] and sustainable choices, in a tight connection to the age and the cultural background.

Author Contributions

All five authors equally contributed in designing and writing this paper. Conceptualization, G.-M.M.-T., S.P., and N.M.F.; methodology, F.M. and D.D.; software, G.-M.M.-T., S.P., and N.M.F.; validation, G.-M.M.-T., S.P., and N.M.F.; formal analysis, G.-M.M.-T., S.P., and N.M.F.; investigation, F.M. and D.D.; resources, G.-M.M.-T., S.P., and N.M.F.; data curation, F.M. and D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M. and D.D.; writing—review and editing, G.-M.M.-T. and S.P.; visualization, N.M.F. and F.M.; supervision, S.P., D.D., and N.M.F.; project administration, G.-M.M.-T., N.M.F., and F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Questionnaire design (constructs and items).

Table A1.

Questionnaire design (constructs and items).

| Construct | Code | Item | Previously used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioral intention | B_i_1 | I will continue to use the mobile commerce to shop for new products | Omar et al., 2021 [45] |

| B_i_2 | If a need to purchase a product online, the mobile commerce would be my first choice | Omar et al., 2021 [45] | |

| B_i_3 | The use of mobile commerce has become a habit for me | Dakduk, 2020 [23]; Ashraf et al., 2014 [46] | |

| B_i_4 | I am addicted to using mobile commerce | Dakduk, 2020 [23] | |

| B_i_5 | I intend to continue using mobile commerce | Venkatesh et al., 2012 [47] | |

| B_i_6 | I will always try to use mobile commerce in my daily life | Dakduk, 2020 [23] | |

| B_i_7 | Using mobile commerce has become natural to me | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46] | |

| Online advertising influence | O_a_1 | In the past 4 weeks I came across social media advertising for the mobile commerce | |

| O_a_2 | In the past 4 weeks I came across YouTube videos advertising for the mobile commerce | Authors’ own contribution | |

| O_a_3 | In the past 4 weeks I came across in apps advertising for the mobile commerce | ||

| O_a_4 | In the past 4 weeks I came across advertising on search engines for the mobile commerce | ||

| O_a_5 | In the past 4 weeks I came across banner ads for the mobile commerce on websites | ||

| O_a_6 | In the past 4 weeks I came across videos for the mobile commerce advertising | ||

| O_a_7 | I use ad blocking software not to come across mobile advertising | ||

| O_a_8 | I am often annoyed by advertising on mobile devices | ||

| O_a_9 | I am often annoyed by the online ads based on my search history on mobile devices | ||

| Social influence | S_i_1 | My friends, family and colleagues encourage me to buy through mobile commerce | Dakduk et al., 2020 [23] |

| S_i_2 | People that are important to me think that I should purchase by mobile commerce | Venkatesh et al., 2012 [47] | |

| S_i_3 | I have bought products/services though mobile commerce, because musicians advertised them | ||

| S_i_4 | I have bought products/services though mobile commerce, because influencers advertised them | ||

| S_i_5 | I have bought products/services though mobile commerce, because TV stars (film stars, comedy, reality TV stars) advertised them | ||

| S_i_6 | I have bought products/services though mobile commerce, because sports people advertised them | ||

| S_i_7 | I have bought products/services though mobile commerce, because models/fashion icons advertised them | ||

| Usage motivation | U_m_1 | Mobile commerce allows me to access product/service information at any time | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46] |

| U_m_2 | Using mobile commerce keeps me well informed about products/services at any time | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46] | |

| entry 4 | U_m_3 | Mobile commerce allows me to find the needed information at any time | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46] |

| U_m_4 | Using mobile commerce is fun | Venkatesh et al., 2012 [47] | |

| U_m_5 | Using mobile commerce is enjoyable | Dakduk et al., 2020 [23]; Ashraf et al., 2014 [46] | |

| U_m_6 | I find using mobile commerce very entertaining | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46] | |

| U_m_7 | I use mobile commerce to enjoy the variety of promotional offers | ||

| U_m_8 | I feel a sense of adventure while using mobile commerce | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46] | |

| U_m_9 | Using mobile commerce is stress relief | ||

| U_m_10 | Using mobile commerce is rewarding | ||

| U_m_11 | Mobile commerce provides me with many features that I can benefit from | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46]; Kim et al. 2009 [48] | |

| U_m_12 | I use mobile commerce to fulfill different tasks and functions in an efficient way | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46]; Kim et al. 2009 [48] | |

| U_m_13 | I use mobile commerce because it is helpful in buying or searching what I want online | Ashraf et al., 2014 [46]; Kim et al. 2009 [48] |

Source: Authors’ own analysis.

References

- Statista. Mobile Retail Commerce Sales as Percentage of Retail E-Commerce Sales Worldwide from 2016 to 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/806336/mobile-retail-commerce-share-worldwide/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Merchant Savvy. Global Mobile E-Commerce Statistics, Trends & Forecasts. 2020. Available online: https://www.merchantsavvy.co.uk/mobile-ecommerce-statistics/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Monetate. E-Commerce Quarterly: Benchmarks. Q2 2019. Available online: https://info.monetate.com/rs/092-TQN-434/images/Q2%20Monetate%20Ecommerce%20Benchmarks.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Corporate Finance Institute. What is Mobile Commerce? Available online: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/ecommerce-saas/mobile-commerce/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Capgemini Research Institute. World Payments Report 2020. Available online: https://worldpaymentsreport.com/resources/world-payments-report-2020/ (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Gardner, B.; Lally, P.; Wardle, J. Making health habitual: The psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2012, 62, 664–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecommerce Guide. Ecommerce in the Mobile Age. Available online: https://ecommerceguide.com/guides/mobile-ecommerce/ (accessed on 26 March 2021).

- Unbounce. The Page Speed Report. 2019. Available online: https://unbounce.com/page-speed-report/ (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Knust, M. A Full-Funnel Guide to Connecting with Mobile Shoppers. Digital Commerce 360. 2019. Available online: https://www.digitalcommerce360.com/2019/10/31/a-full%e2%80%91funnel-guide-to-connecting-with-mobile-shoppers/ (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Barilliance. Complete List of Cart Abandonment Statistics: 2006–2021. Available online: https://www.barilliance.com/cart-abandonment-rate-statistics/ (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Bigne, E.; Ruiz, C.; Sanz, S. The Impact of internet user shopping patterns and demographics on consumer mobile buying behaviour. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2005, 6, 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Global Web Index. 46% of Internet Users Purchasing via Mobile. 2016. Available online: https://blog.globalwebindex.com/chart-of-the-day/46-of-internet-users-purchasing-via-mobile/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Episerver. Reimagining Commerce 2020. Available online: https://www.episerver.com/globalassets/03.-global-documents/reports/reimagining-commerce-2020-episerver.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Saprikis, V.; Markos, A.; Zarmpou, T.; Vlachopoulou, M. Mobile shopping consumers’ behavior: An exploratory study and review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunsakul, K. Gen Z consumers’ online shopping motives, attitude, and shopping intention. Hum. Behav. Dev. Soc. 2020, 21, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Maree, R.B.; Gilal, A.R.; Waqas, A.; Kumar, M. Role of age and gender in the adoption of m-commerce in Australia. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2019, 6, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Suresh, S.; Sharma, S. Factors influencing consumers’ attitude towards adoption and continuous use of mobile applications: A conceptual model. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 122, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, J.; Frade, R.; Ascenso, R.; Prates, I.; Martinho, F. Generation Z and key-factors on e-commerce: A study on the portuguese tourism sector. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AdColony. Gen Z Effects in Today’s Digital World. 2020. Available online: https://www.adcolony.com/blog/2020/08/18/gen-z-effects-in-todays-digital-world/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Global Web Index. The You the Nations: Global Trends among Gen Z. 2019. Available online: https://www.globalwebindex.com/reports/global-trends-among-gen-z (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Global Web Index. GWI Commerce: Global Web Index’s Bi-Annual Report on the Latest Trends in Online Commerce. Flagship report Q1 2017. Available online: https://blog.globalwebindex.com/trends/q1-2017-upcoming-reports-from-globalwebindex/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Global Web Index. Commerce: Global Web Index’s Flagship Report on the Latest Trends in Online Commerce. 2019. Available online: https://www.globalwebindex.com/reports/commerce-2020 (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Dakduk, S.; Santalla-Banderali, Z.; Siqueira, J.R. Acceptance of mobile commerce in low-income consumers: Evidence from an emerging economy. Heliyon 2020, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirtha, R.; Sivakumar, V.J.; Hwang, Y. Influence of perceived risk dimensions on e-shopping behavioural intention among women—A family life cycle stage perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 320–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Park, J.W. Investigating factors influencing the behavioral intention of online duty-free shop users. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Osman, A.; Salahuddin, S.N.; Romle, A.R.; Abdullah, S. Factors influencing online shopping behavior: The mediating role of purchase intention. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 35, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-García, N.; Gil-Saura, I.; Rodríguez-Orejuela, A.; Siqueira-Junior, J.R. Purchase intention and purchase behavior online: A cross-cultural approach. Heliyon 2020, 6, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudaruth, S.; Busviah, D. Developing and testing a pioneer model for online shopping behavior for natural flowers: Evidence from mauritius. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2018, 13, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Bhatti, A.; Mohamed, R.; Ayoup, H. The moderating role of trust and commitment between consumer purchase intention and online shopping behavior in the context of Pakistan. J. Glob. Entrepr. Res. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Kim, E.Y.; Kumar, S. Testing the behavioral intentions model of online shopping for clothing. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2003, 21, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septiani, R.; Handayani, P.W.; Azzahro, F. Factors that affecting behavioral intention in online transportation service: Case study of GO-JEK. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 124, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perju-Mitran, A.; Negricea, C.I.; Edu, T. Modelling the Influence of online marketing communication on behavioural intentions. Netw. Intell. Stud. 2014, 2, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Mao, E. From online motivations to ad clicks and to behavioral intentions: An empirical study of consumer response to social media advertising. Psychol. Mark. 2016, 33, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryani, S.; Motwani, B. Discriminant model for online viral marketing influencing consumers behavioural intention. Pac. Sci. Rev. B Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 1, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatimah, H.; Susanto, P.; Abdullah, N.L. Hedonic motivation and social influence on behavioral intention of e-money: The role of payment habit as a mediator. Int. J. Entrep. 2019, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.J. Behavioral intention formation: The interdependency of attitudinal and social influence variables. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, E.H. Attitude, social influence, personal norm, and intention interactions as related to brand purchase behavior. J. Mark. Res. 1974, 11, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Web Index. Social Commerce: Understanding How Social Media and Commerce Merge in Day-to-Day Online Behaviors. Trend Report 2019. Available online: https://www.globalwebindex.com/reports/social-commerce (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Yin, X.; Wang, H.; Xia, Q.; Gu, Q. How social interaction affects purchase intention in social commerce: A cultural perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, S.S.; Alkelani, A.M.; Tamam, E.; Charles Feng, G. Habit as a moderator of the association of utilitarian motivation and hedonic motivation with purchase intention: Implications for social networking websites. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloglu, C. Consumer motivation and concern factors for online shopping in Turkey. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S. Purchase intention in the online open market: Do concerns for e-commerce really matter? Sustainability 2020, 12, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefany, S. The effect of motivation on purchasing intention of online games and virtual items provided by online game provider. Int. J. Commun. Inf. Technol. 2014, 8, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, S.; Mohsen, K.; Tsimonis, G.; Oozeerally, A.; Hsu, J.-H. M-commerce: The nexus between mobile shopping service quality. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.R.; Thongpapanl, N.; Auh, S. The application of the technology acceptance model under different cultural contexts: The case of online shopping adoption. J. Int. Market. 2014, 22, 68–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jin, B.L.; Swinney, J.L. The role of e-tail quality, e-satisfaction and e-trust in online loyalty development process. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2009, 16, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gîrboveanu, S.R.; Crăciun, L.; Meghisan, G.-M. The role of advertising in the purchase decision. An. Univ. Oradea. 2012, 17, 897–902. [Google Scholar]

- Sivathanu, B. The Effects of trust, security and privacy in social networking: A security-based approach to understand the pattern of adoption. Interact. Comput. 2018, 22, 428–438. [Google Scholar]

- Savita Panwar, P.T. Using UTAUT 2 model to predict mobile App based- shopping: Evidences from India. J. Ind. Bus. Res. 2017, 9, 248–264. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Weng, Q.; Zhu, N. The relationships between electronic banking adoption and its antecedents: A meta-analytic study of the role of national culture. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, N.M.; Meghisan, G.M.; Nistor, C. Multiple linear regression equation for economic dimension of standard of living. Finant. Provocarile Viitorului Financ. Chall. Future 2016, 1, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Individuals- Internet Use (Last Internet Use: In the Last 12 Months). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/isoc_ci_ifp_iu/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Burger-Helmchen, T.; Meghisan-Toma, G.-M. EU policy for digital society. In Doing Business in Europe; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 195–212. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).